Civic Arts

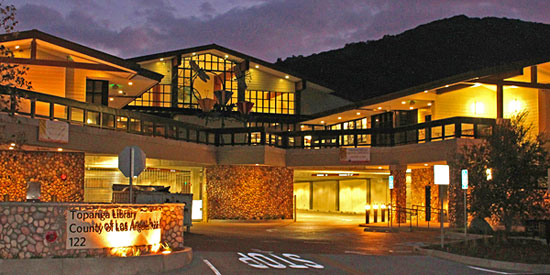

New library tells Topanga’s story, too

January 17, 2012

The new Topanga Library reflects the spirit and sensibilities of the artistic Santa Monica Mountains community.

It may not be easy to tell a book by its cover, but when the county’s newest library opens this weekend, visitors will have no trouble knowing which community’s stories are surrounding them.

From the design to the public artwork, the long-awaited Topanga Public Library, which will be dedicated on Saturday, is an organic outgrowth of the community it will soon serve.

“They tried to make it as homegrown as possible,” says Topanga artist Matt Doolin, who, with his brother Paul and his mother Leslie, created a circular tile mural of an idyllic Topanga landscape that will anchor the library’s main room.

The 11,293-square-foot, silver LEED-certified building broke ground in 2008 and has been in the works for more than a decade; for generations, residents of the mountain community had made do with other towns’ libraries and a visiting bookmobile. (Click here for a gallery of early construction work.)

Although Los Angeles County funded the $19.6 million project, it was clear from the start that the iconoclastic community, filled with environmentalists and artists, would insist on weighing in on the building’s aesthetic and carbon footprint.

“There are a lot of stakeholders in Topanga,” laughs Rebecca Catterall, former president of the Topanga Canyon Gallery and a 30-year-resident of the rustic enclave.

“There’s a sense of a spiritual connection there that’s not like any other place, and I think it’s important to the people,” agrees Norman Grochowski, who spent most of his career in Topanga and whose massive-yet-whimsical steel-and-ceramic book flowers bedeck the library’s entry.

“Topanga is a land within a land, a place far away.”

So a local design advisory committee was convened to determine the rustic “lodge” look of the North Topanga Boulevard building, and the library was built to the latest green construction standards.

Meanwhile, in accordance with county policy, one percent of the cost of construction was allocated for the incorporation of civic art into the project. A second local committee, this one pulled from the local art scene by the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, commissioned pieces by four local artists. (Click here for an extensive photo gallery of the of the library’s artwork on Green Public Art’s Flickr page.)

Catterall, who sat on the arts committee, says the group methodically culled 29 entries in search of artists who were both representative of the community and who worked on an architectural scale. Patricia Correia, a Topanga-based art dealer and former gallery owner who served with Catterall, says the artists were chosen first and then asked to make pieces for specific areas of the building.

“A lot of times in public art, people pick a beautiful sculpture and then find out it’s too small or too big.”

Some aspects of the new library ended up being literally rooted in Topanga: A podium, two Adirondackchairs, two rocking chairs and a picnic table were made from trees that had had to be removed during construction. That work, set in motion by Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s office, was done by Don Seawater, whose California-based Pacific Coast Lumber Co. is a leader in the use of reclaimed wood and urban forestry.

Artist and art teacher Megan Rice, who did two papier mache sculptures for the library’s children’s section, also honored the fallen trees—two oaks and two pines—by using one of the stumps as the base for “A Great Tale,” which depicts a little boy reading to his faithful dog.

“I’ve lived in Topanga since 1956, and when I heard they were looking for artists with a vested interest in Topanga, I felt, ‘That’s me’,” says Rice, who was 5 when her parents moved to the community.

“My mother was the children’s librarian at Topanga Elementary School for eight or ten years, and I grew up with the bookmobile—in fact, in my early childhood, it was a very big part of my life because we had few neighbors, and for a long time my mother didn’t have a car, so getting a big stack of books there was a source of great excitement for me.”

Local potter Jim Sullivan, a resident since the early 1960s, remembered the Topanga childhood of his now-grown daughter when he designed the ceramic tile “rug” just inside the front entrance. “When she was in fourth grade, she went to the Adamson House inMalibu, and the docent stopped them at the front door and pointed to the threshold,” says Sullivan. “She said, ‘Does anybody know what that is?’”

Only Sullivan’s daughter, the child of a ceramist, knew that the design on the floor was a broken tile mosaic. When the guide explained that broken tile was often used in doorways because of ancient lore that it kept out evil spirits, Sullivan says his daughter became so excited that she begged him relentlessly to install similar mosaics in their own house.

Since then, he says, he has done a number of such installations, and when he heard about the library commissions, he felt a piece of broken-tile floor art would be perfect for Topanga’s new landmark. His 8-foot-wide piece, made entirely by hand, he says, depicts a spark growing into a flame of intellect and community.

All the artists who contributed work are established and well known in Topanga. The Doolins have done murals at local landmarks ranging from Disneyland California Adventure to public pools in South Los Angeles. Grochowski, who now lives in Crescent City, Ca., but visits Topanga several times a year, has shown work at LACMA and the Laguna Art Museum.

Rice’s work has been exhibited throughout California, and Sullivan, whose ceramics are in a number of private collections, has done historic restoration work from Malibu to Pasadena; for many years he co-owned Malibu Ceramic Works, a Topanga tile company that replicated historic tiles.

Correia says the work by Sullivan and the Doolins echoes Topanga’s long history as a center for ceramic artwork and the sculptures by Rice and Grochowski brought variety.

“There aren’t a lot of libraries getting built anymore,” she notes. “It was exciting, and we wanted to bring a three-dimensionality to the space, take it beyond just a big painting or a big mural outside.”

The new library “is incredibly important,” adds Correia.

“We don’t really have an everyday kind of communal place that isn’t a commercial space,” she says. “This is going to bring the community together in a way that deals with knowledge and culture and imagination. I can’t wait.”

The library’s grand opening will take place Saturday, January 21, at 11 a.m. The address is 122 N. Topanga Canyon Blvd.

Some of the library's furniture, such as this bench, was crafted from trees that were cleared for the facility.

Posted 1/17/12

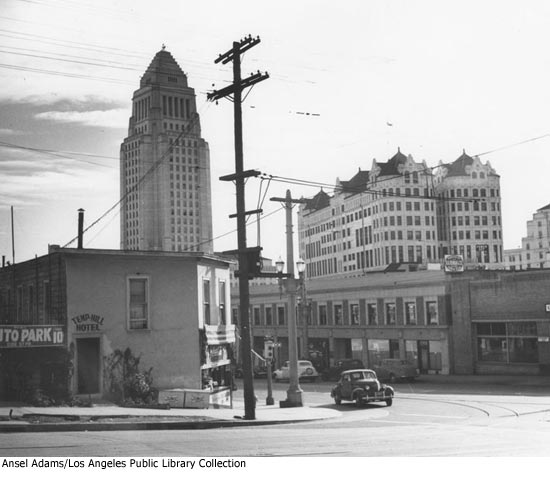

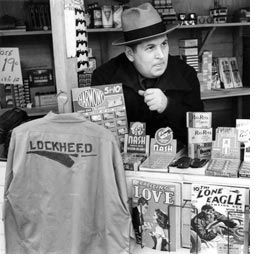

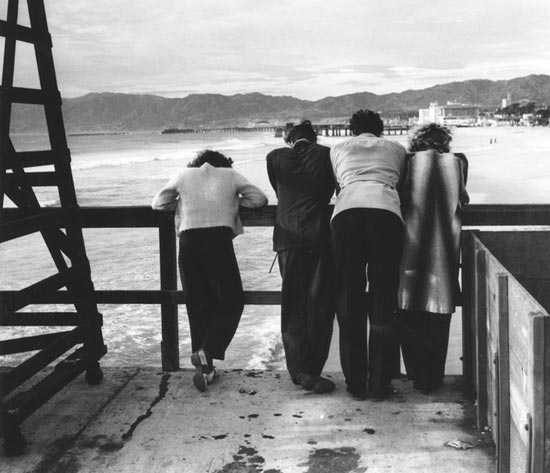

Ansel Adams and a vanished Los Angeles [updated]

February 17, 2011

He gave the world majestic images of Yosemite, not to mention the unforgettable “Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico.” But Ansel Adams was no sentimentalist when it came to disposing of his old work.

In the early 1960s, the celebrated photographer happened upon a trove of negatives and small contact prints dating back to an assignment for Fortune magazine in Los Angeles. Some of his photos ran in the magazine’s March, 1941 issue with a story on the aerospace industry’s WWII buildup in Los Angeles.

Ansel Adams/Los Angeles Public Library Collection

But Adams had photographed far more during the assignment—bowling parties, quirky architecture, trailer park life, a cemetery reposing next to oil wells. So he wrote to the Los Angeles Public Library offering the images not as art but as a slice of the city’s history. (His letter is here.)

“The weather was bad over a rather long period and none of the pictures were very good,” he wrote. “If they have no value whatsoever, please dispose of them in the incinerator.”

Fortunately, the city did not put the images out with the trash. The library accepted the photos and gave Adams a letter valuing them at $150 for his income tax purposes—more than the $100 valuation he’d suggested.

Since then, the photos have periodically been “rediscovered” and given a public viewing. (Here’s a link to Huell Howser’s “California’s Gold” segment; a Flickr gallery is here, and NPR’s online feature “The Picture Show” has featured them as well.)

Ansel Adams/Los Angeles Public Library Collection

Fans of photography and Los Angeles history had a chance to learn more about the images during a free presentation last year at the library’s Los Feliz Branch. The presentation by Richard Stanley was part of the library’s “Architecture & Beyond” lecture series. (See details in update below of a gallery exhibition of the images that begins Feb. 18, 2012.)

“He photographed virtually the whole city, from Santa Anita to the Santa Monica Pier,” said Stanley, who’s a realtor as well as an Adams admirer and frequent photography lecturer in the series. The images demonstrate that Adams “was a working photographer, not just a fine artist.”

Christina Rice, acting senior librarian for the Los Angeles Library, last year initiated a three-month project to better present the images online and to research the historic (and often vanished) locations where the photos were made. But some of the details seem to have been lost to the ages—like the location of that cemetery by the oil wells.

Still, Rice said, “”from a Los Angeles history viewpoint, I think they’re amazing.”

Ansel Adams/Los Angeles Public Library Collection

Posted 2/17/11

Updated 2/1/12: L.A. Observed reports that the photographs will be getting a gallery show, with sales benefitting the Library. The exhibit opens Feb. 18. Details are here.

Changing of the guard at Watts Towers

November 3, 2010

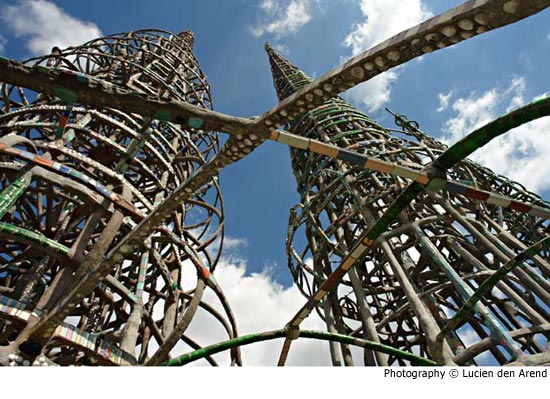

Minding a masterpiece isn’t easy. The Watts Towers have been among Los Angeles’ great public treasures, but their upkeep has been a full-time challenge almost since they were finished in 1954.

Rattled by earthquakes, assaulted by rainstorms, the fantastic, filigreed metropolis erected by an Italian-born amateur stonemason in a South-Central barrio is perpetually in a state of deterioration. The mortar cracks. The tiles are forever falling. The joints are damp with seepage and rusting from within.

Late last month, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art announced plans to lend a hand to the recession-slammed city in ensuring that Simon Rodia’s renowned public sculpture is preserved. The art world is applauding the one-year agreement, in which LACMA will contribute expertise, staff and — most crucially — fundraising assistance.

And cheering the loudest are Zuleyma Aguirre and Virginia Kazor.

For some 20 years, Aguirre and Kazor have tended the towers. Before her retirement this summer, Kazor spent 19 years as the historic site curator, managing the conservation effort for the city’s cultural affairs department. Aguirre, her lead conservator, handled all the on-site restoration, tending every inch of concrete, tile and metal until she was sidelined two years ago by an injury on the job.

For some 20 years, Aguirre and Kazor have tended the towers. Before her retirement this summer, Kazor spent 19 years as the historic site curator, managing the conservation effort for the city’s cultural affairs department. Aguirre, her lead conservator, handled all the on-site restoration, tending every inch of concrete, tile and metal until she was sidelined two years ago by an injury on the job.

Together, the two women – one an art historian raised in Los Angeles, the other an El Salvador-born expert in the restoration of pre-Columbian artifacts – have shepherded the landmark through the Los Angeles riots, the Northridge earthquake and countless storms and budget woes. This week, they sat down with ZevWeb to talk about the labor of love that became not only Simon Rodia’s life’s work, but theirs as well.

“The first time I came to the towers,” Aguirre remembers, “it was 1988. They were just – oh! Amazing! Rodia’s work made me feel like I really had not done too much in the world.”

She had come to the United States in the early ‘80s on a grant to visit museums, and remained, reluctant to return to her country’s civil war. The Watts job became hers after she hired on with a city consultant working on the towers’ preservation. The project, she immediately realized, would be like no other.

“I had come from working in museums,” she says, “and the towers were just so different. There were no drawings we could find, no blueprints. We had to do X-rays to learn how he did the connections on 5,000 joints.”

“I had come from working in museums,” she says, “and the towers were just so different. There were no drawings we could find, no blueprints. We had to do X-rays to learn how he did the connections on 5,000 joints.”

In 1991, Kazor became Aguirre’s supervisor on the project. Already a longtime curator for the city, her relationship with the towers was more than three decades old. As a student in 1958 at the University of Southern California, she had been assigned to report on them by her design teacher.

“I was so fascinated that after that, when I met someone and found him interesting, I’d always take him first to the Watts Towers,” she remembers, laughing. “And if — and only if — they liked them, then I’d go out with them.”

Then and now, she says, she was moved by the assemblage – a collection of 17 structures, built over 33 years by an eccentric handyman. Constructed by hand out of scraps and castoffs, the towers’ famed spires soar up to 99 feet over their impoverished surroundings.

Kazor, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s shortly after being assigned to Rodia’s project, connected with the resolve that fueled it: “They’re ours and they’re absolutely unique. And they are a testament to what one person can accomplish, if they just set their minds to it.”

That determination, the women say, was what most impressed them, day after workday.

“Rodia was a common laborer who took part-time jobs,” Kazor says, “but he was sort of intuitively brilliant. He took any steel he could find — rebar if it was available, but he’d use water pipe or anything he thought would work.

“And he didn’t weld. He overlapped the pieces, wrapped the overlapped portion with wire to hold them together, and then covered that with chicken wire. Then he took a very dry concrete mix — you could pick it up by the handful and it would hold its shape — and he’d press that into the chicken wire. Then he would press into that the decorative elements he had chosen. Seashells or tile or the impression of a tool or broken glass.”

But his work didn’t end there. “After that, he would have to keep the concrete moist by spraying it with water for more than a week,” Kazor says. “And he did this by climbing up the towers as if they were scaffolding. And he would carry on his arm a bucket with whatever materials he needed. And every time he needed more materials, he had to go all the way back down to the ground and then all the way back up again.”

Honoring that artistic commitment has required its own brand of determination. After every Santa Ana wind or winter rainstorm, tile and bits of concrete shower from the structures onto the ground. Moisture is a constant challenge.

“Once water gets past the decorative surface and through the concrete, the steel inside it rusts,” says Kazor. “And then the rust expands. And the cracks get larger, and more water gets in, and eventually the interior steel structure rusts away.”

Part of Aguirre’s job, she says, was to walk the site with her crew daily, picking up fragments and carefully documenting where they had fallen and where they belonged.

“Early on in the project, the whole structure was completely photographed, and broken down into a 4-foot grid,” says Kazor. “So each worker, every day, would be assigned a certain area, and at the end of the day, record what he did there.”

That painstaking documentation, she says, has been the key to FEMA and other grants that have underwritten tower restoration again and again.

The work hasn’t always been safe.

“Once,” Kazor says, “one of our construction workers was on the scaffolding 40 feet in the air, and an earthquake hit. And he said, ‘Please don’t fire me, but the scaffolding was shaking so hard, I had to hang onto the tower.’ When he looked down, he said, he could see the wave of the earthquake come down the street, lifting the backs of the parked cars.”

In fact, Aguirre has been unable to work for more than two years, after having been struck by a piece of scaffolding that damaged two cervical vertebrae in 2008. It was not her first on-the-job injury. In 2001, she says, she was mugged as she arrived for work early one morning, carrying her purse and her laptop.

“This young fellow asked me for the time, and when I didn’t know, he went with his fist in my face,” Aguirre remembers. The blow broke six of her teeth and severed an artery, and Kazor says Aguirre nearly bled to death before she was found.

Yet for all the challenges, the women say, the towers have been deeply rewarding.

“It’s magic there,” says Aguirre. “I felt I could hear Rodia’s steps some days, when everybody went to lunch and I stayed there alone. From the top, you can see all over the city. It’s gorgeous. You have a whole other vision of Watts. Or just sitting there below, looking up. Hearing all the Watts sounds. The neighbor sounds – the rap, the Mexican music, the lambada, the smell of the materials. The mix. Everywhere you look, it is art.”

This fragile, unconventional beauty, Kazor says, is why LACMA’s involvement is so welcome.

“The city does not really have the resources any more to do what needs to be done,” she says, noting that by the time she retired, the manpower the city had committed to the towers had fallen from about 14 full- and part-time workers to two.

“The Watts Towers are as important as any work in a museum. They are like the Eiffel Tower, or the Millennium Wheel in London. They’re a great gift to Los Angeles.”

Watch this short film on the Towers

Posted 10/28/10

Twinkling YOLA stars

October 15, 2010

Like its young participants, Youth Orchestra Los Angeles is growing. Check out the magic moment in this video (see below) when the kids at the organization’s latest outpost first receive their instruments.

YOLA’s newest program–the second of its kind–is jointly sponsored by Heart of Los Angeles and the L.A. Philharmonic and serves children in the Rampart District.

Read Zev’s blog on this innovative program, modeled on Venezuela’s legendary El Sistema, which produced Gustavo Dudamel (you may have heard of him.) And check out our other coverage here.

Posted 10/15/10

Learning lessons by HeArt

October 7, 2010

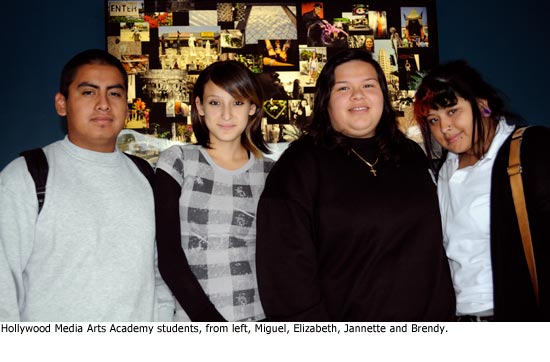

Brendy Giron, a.k.a. “Jinxie,” ditched school daily to tag with her boyfriend. Her classmate, Janette, cut class to chill by the gym.

Miguel Hernandez was so brazenly truant that sometimes as he sneaked out the school door, he’d pass his own mother, who would stake out the campus entrance in a vain attempt to intercept him. Outside, his girlfriend, Elizabeth, would be waiting, having blown off her classes as well.

This is how high school kids end up in alternative and continuation schools in Los Angeles County, which is where all four teenagers eventually landed. Their new classroom, however, is no ordinary alternative.

Every morning, they get five hours of regular classroom instruction; then, in the afternoons, artists come in to teach painting, photography, video production, dance, water color and other arts courses. If they show promise—and stay in class—they have a shot at internships at production companies and art institutions.

“This is an arts high school specifically for alternative education students,” says Cynthia Campoy Brophy, proudly striding down a bright blue hallway in the Hollywood Media Arts Academy.

Jointly run by the Los Angeles County Office of Education (LACOE) and The HeArt Project, a nonprofit founded by Campoy Brophy that has offered arts programs to at-risk students in the county for 18 years, the academy is the newest—and smallest—public school of the arts in L.A. County.

The academy has been open for a year and a half, although the HeArt Project took over the arts component only a few months back; an open house to celebrate the new school year was held in September. Current enrollment is around 30 students, but officials hope that, as the word gets out, that number will increase.

“What we’re trying to do is use The HeArt Project and artists who work with the kids to inform and really engage them at a deeper level of career opportunities in the entertainment industries,” says Gerald Riley, assistant superintendent of educational programs at LACOE.

Situated in a low-slung building off Santa Monica Boulevard, the school looks a lot like the show business warehouses that surround it. Inside, however, its rooms are spacious and airy, the walls freshly painted in bright colors and covered with words intended to inspire ambition: sound engineer, director, percussionist, cartoonist, costume designer. The lettering over the doorway in the bright yellow lobby warns, “You are entering a creative space.”

Campoy Brophy, executive director of The HeArt Project, said the split school day is modeled after the more renowned Los Angeles County High School for the Arts, colloquially known as LACHSA. : “The students here have 10 hours of arts programming a week,” she says. “They do their core curriculum in the mornings and we get them in the afternoons.”

Unlike LACHSA students, who must audition and submit portfolios of artwork, however, the Media Arts Academy kids usually have no prior art training and find the school via guidance counselors or word of mouth. Often, Campoy Brophy says, they’re the sort of students “who only come to school on the arts day”—creative but struggling kids who, for a variety of reasons, are failing to thrive in conventional high schools.

Unlike LACHSA students, who must audition and submit portfolios of artwork, however, the Media Arts Academy kids usually have no prior art training and find the school via guidance counselors or word of mouth. Often, Campoy Brophy says, they’re the sort of students “who only come to school on the arts day”—creative but struggling kids who, for a variety of reasons, are failing to thrive in conventional high schools.

Some have had chaotic home lives. Some have trouble saying no to peer pressure. Some have just sold themselves short or missed too much school or fallen in with a bad crowd.

“They aren’t necessarily problem kids, they just need a smaller setting,” says Principal Jennifer Flores, who oversees the academy and six other alternative schools for LACOE.

Student poetry on the walls of the dance room hints at their journeys: I am random and loud/I pretend I’m a makeup artist… I am handsome and nice/I pretend to be Ronaldinho… I am funny and nice/I worry about my homies…

“They come from all over,” smiles Elizabeth Meza, who works in the school office. “Koreatown. Santa Monica. Pacoima. One boy came in every day from Norwalk on public transportation. He said he liked it because it was a safe place for him and the art kept him out of trouble. He’s going to graduate in December, and he’s going to community college, I hear.”

Brendy Giron says she was a middle school student in the San Fernando Valley when her mother began moving around in search of a better job. They ended up in Koreatown, and Giron enrolled at Los Angeles High School, where she met a boy in her second period class who shared her fascination with graffiti art, or, as they termed it, “graf.”

“He had this thing on his notebook, and I go, ‘Oh, you’re a graffer,’ and he’s like, ‘Yeah, what do they call you?’ And I told him what they call me, which was Jinxie. And he was called Obie. And we were all in, like, the love zone, and when he would go writing, I would go writing, too.”

But their habit took on a life of its own, she says. She spent less and less time in classes. She switched schools, but jumped the fences to be with him. She tried independent study and ditched the test days.

One night, she says, she got caught tagging on a mid-city rooftop. Meanwhile, her boyfriend was getting into his own scrapes. Eventually, their pastime became less novel. When her boyfriend told her about the academy, where he had been enrolled for a time, she begged her mother to let her go there. The boyfriend ended up in a juvenile probation camp, but Giron, now 18, says she hopes to study fine art someday.

“I don’t want people to look at my art and be, like, ‘Oh, that’s just tagging.’ I want to do it right, you know?”

Other students see the academy more as a place to learn a new skill. Janette—who school officials insisted be identified only by her first name because she is 16 and a minor—says the promise of art at the end of the day kept her in the classroom: “There was nothing at my other schools that I was that interested in.”

For Elizabeth, 17, the academy has been a lifeline: “I don’t know where I’d be if I didn’t come here. It got the point where my old school didn’t want me and I just didn’t care anymore.”

The school was reluctant at first to admit her to the same school as her boyfriend, but she has applied herself, and for the first time in her life she is earning As and Bs in academic classes. “I just entered the 10th grade, which for me was a big deal. I have a lot of catching up to do.”

Her boyfriend, 18-year-old Miguel Hernandez, says he has stopped cutting class (a relief to his parents) and is hoping to win an internship after he graduates in December. Campoy Brophy says she has been talking to a commercial television production company about the student. As it turns out, she says, he has a knack for cameras.

“Honestly, I didn’t want to come here at first,” he recalls. “I thought it was going to be just another continuation school where they give you a packet of work and tell you to sit down and do it.” But during the summer, he learned photo editing and photography, “and I loved it.”

“It’s like, you can pass by someone or something a thousand times and you wouldn’t pay attention to it. But with pictures, you learn to pay attention. You see things in a different way—a better way.”

Local arts grants ripple out

July 14, 2010

Money’s tight these days—which makes being on the receiving end of a grant from the Los Angeles County Arts Commission that much sweeter. That’s doubly true of some of the non-profit organizations receiving funds for the first time.

The grant newbies include the Buzzworks Theater Company, the Invertigo Dance Theatre, the Los Angeles-St. Petersburg Russian Folk Orchestra and the Madison Project, an independent nonprofit that puts on cultural programs at the Broad Stage on the Santa Monica College campus.

“We weren’t sure, with times being what they are, that we were going to get anything,” said Deborah Reed, Buzzworks’ director of development, which will use its $4,000 grant to pay its artists. “We’re just thrilled.”

In all, the commission awarded $4.1 million in two-year grants to 166 organizations across the county. The grant amounts are smaller this year, but were enhanced somewhat by the Board of Supervisors, which recently voted for a one-time infusion of funds from county reserves to help bridge the shortfall.

The full list of 3rd District groups receiving grants is here. They range from the Topanga Symphony, which received $3,500 for its free concert series, to the Skirball Cultural Center, granted $141,682 to support its Sunset Concerts program.

A new park gets ready to make a splash [updated]

June 4, 2010

The giant color-coded flow chart and to-do list have come down in the front room of Dawn McDivitt’s La Crescenta home. Her husband’s delighted.

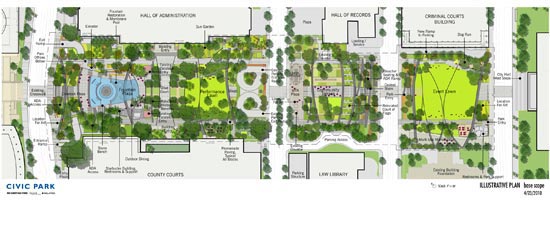

As for all the folks about to have their parking, commuting and coffee-drinking patterns altered by the new Civic Park that McDivitt is planning, let’s just say they may not be singing such a happy tune. When McDivitt’s poster boards come down, that means the heavy machines are about to get to work on a 12-acre park in the heart of the Civic Center.

For downtown employees, patrons of the Music Center, people on jury duty and anyone else who lives, drives or walks in the area, this promises to be a summer to remember.

The $56 million park project is scheduled to come before the Board of Supervisors on June 29. If approved by supervisors and the joint powers authority overseeing the project, construction is expected to get underway in mid-July. That will trigger a series of logistical changes that, at least during the initial weeks, will upend many rituals of daily life in the Civic Center ecosystem.

So McDivitt—a capital projects manager in the county’s Chief Executive Office who’s been heading up the park building effort for the last couple of years—is on a one-woman communications crusade.

“Even if I’m having lunch with a friend who works at the courts, I can say, ‘Do you know about the Civic Park project?’ “ McDivitt says. “People have said to me, ‘Your [business] cards are all over the county.’ “

Which is fine with McDivitt, who’s eager to spread the word about a park that is intended to “remake an often overlooked public space into a spectacular community gathering space that will provide an iconic park for Los Angeles,” according to a February 16 letter to supervisors about the project.

The park will extend from the Music Center to City Hall. Building it means turning what is now the County Mall into a construction zone that will be largely off-limits for the next two years. When finished in June, 2012, the park will provide a long-awaited “sense of place” downtown—not to mention vistas stretching from Grand Avenue straight to City Hall, thanks to the relocation of some county parking ramps.

The park, to be built on the County Mall and the Criminal Courts building parking lot, will have four distinct levels featuring amenities ranging from a community terrace area showcasing plants from around the world to a restored historic Arthur J. Will Memorial fountain, complete with a new wade-able membrane pool. There also will be a performance lawn, a grand event lawn, ADA-accessible walkways, an area for chess players and even a dog run. Sixteen media jacks will make it possible to present, say, an opera on a big screen at the event lawn, or a concert heard by 18,000 people throughout the site.

In preparation for breaking ground on the park, which initially was conceived as part of the now-stalled Grand Avenue Project, McDivitt is holding weekly construction meetings with the builder, developer and representatives of nearby buildings, including the Music Center, where “South Pacific” is playing this summer at the Ahmanson and “The Lieutenant of Inishmore” will be at the Mark Taper Forum. Perhaps the biggest initial impact on Music Center employees will be the loss of their paid monthly parking spots; 300 will be relocating to new spaces during construction.

The Music Center’s chief operating officer, Howard Sherman, says construction-related inconveniences are no big deal.

“It’s a great thing for the Music Center to have this iconic park in our backyard,” he says. “It’s a minor pain for what we’ll be getting.”

McDivitt also has met with representatives of the Colburn School and the Los Angeles Unified School District, whose arts high school is on Grand Avenue, near the park site. And she holds monthly meetings with the parking and building managers of all the structures near the planned park. Through them, she hopes to spread the word about coming changes that will affect their workers.

At the downtown Criminal and Superior courthouses, which flank the new park site, the reality of life in a construction zone is sinking in.

“In both facilities, it’s going to be a significant disruption and inconvenience for everybody, judges and employees,” says Allan Parachini, Superior Court public information officer.

He notes that the Civic Park eventually will be a “great resource” for downtown. But he ticks off a list of difficulties that must be overcome—or tolerated—first. For starters, there will be noise, particularly in judges’ chambers, which will be closer to construction areas than the courtrooms. (McDivitt, who’s held a series of meetings with judges, says heavy duty demolition work will take place on weekends.) With one of the Superior Court’s entrances closed during construction, people entering the courthouse will likely experience more delays at security screening points at the remaining entrances. And the traditional Grand Avenue space for news conferences will be off-limits, as will the parking lot behind the Criminal Courts building where media satellite trucks have descended en masse during big trials.

“The only good part: we do note with gratitude that access to Starbucks will continue,” Parachini says

This Starbucks isn’t just any java joint. Although it’s tucked away and invisible from the street, this is the place that caffeinates much of the downtown bureaucracy, buoys armies of weary jurors and gives lawyers a place to park their overstuffed briefcases.

But it’s located in the County Mall construction zone between Superior Court and the Hall of Administration. So workers at the hall soon will encounter an 8-foot high barricade separating them from their quickest route to Starbucks—a barrier that may prove irritating to those in need of a fast coffee fix. For them, McDivitt has worked out a subterranean route that goes through the lower level of the Hall of Administration parking lot and up to the mall via escalator.

Eventually, the café will relocate to a new, bigger building in the park near the fountain. Putting the store out of commission was not really an option since Starbucks’ contract with the county runs through 2012.

For the public at large, there’s a bigger potential headache looming.

When construction starts, a rerouting of traffic into and out of the Hall of Administration garage by way of the Music Center will send more vehicles southbound on Hill Street and Grand Avenue toward the busy Metro station at 1st and Hill. With lots of pedestrians flocking to the station, traffic could back up.

“That’s what I’m worried about,” McDivitt says. To help ease backups, McDivitt is working with the city Department of Transportation on timing of the traffic signals and, possibly, on prohibiting turns from Hill onto 1st during peak hours.

It seems apt that McDivitt, 52, an L.A. native and lifelong outdoorswoman who loves to fish, drew this particular assignment. She certainly has no fear of challenges; she and her husband are planning to build a fishing lodge/bed and breakfast on land they own in tiny Bamfield, Canada, on Vancouver Island.

McDivitt’s boss, Jan Takata, says she has a “rare combination” of qualities that made her right for the job—lots of experience handling high-profile, complex projects and an understanding of finance. An added plus was that she was already working on the Grand Avenue Plan, of which the park is an offshoot.

“She’s terrific,” Takata says.

So far, McDivitt has been too busy to imagine exactly how she—a 20-year county employee—might take advantage of a new urban park that soon will take shape right outside her doorstep.

“I haven’t even thought of that,” she says. “I just want to get the shovel in the ground.”

To that end, she’s had to occupy herself mostly with what might go wrong—from traffic concerns to possible water issues in the garage.

“Part of my job is to anticipate,” she says. “For me, it’s, ‘What’s the worst case scenario?’ I’ve got to think of those things so we can prepare for it.”

For all her attention to detail, though, McDivitt doesn’t want anyone to get the wrong idea about the proliferation of poster board at her home during the project’s early days.

“It only took over the front room,” she says. “Just one wall.”

Posted 6-04-10

Updated 7/8/10: A groundbreaking for the project is scheduled for Thursday, July 15. The public is welcome; the invitation is here.

Helping veterans, one berry at a time

May 27, 2010

Strawberry Flag is a living work of art. It’s also a social experiment, an adventure in aquaponic gardening, a village green, a place to ride a power-generating exercise bike, to silkscreen a T-shirt, to sample a raw food lunch—or to simply sit in a tent, sipping tea while nibbling an old-fashioned biscuit with hand-crafted jam.

Most powerfully of all, it’s a place where human beings are finding that great sustenance comes in small berries.

“To get to dig in the ground for me is a pleasure. To be close to the ground—to me, that’s close to God,” says Bobby Shelton, 75, an Army veteran who served in the Korean War and now is seeing action on the front lines of Strawberry Flag.

The experimental art installation on the grounds of the Veterans Administration campus in West Los Angeles is the brainchild of artist Lauren Bon, who, together with Dr. Jonathan Sherin of the VA, saw the possibility of creating a grand and evolving work on the site. The project is being funded by the Annenberg Foundation, by way of Bon’s Metabolic Studio.

Nestled on an all-but-forgotten quad on the VA grounds, the flag is made up of seven “stripes” of strawberries. The berries were rescued from an abandoned field in Rosemead and are now growing in pots set into white piping. Recycled and filtered L.A. River water pumps through the pipes, powered by a row of stationary bikes hooked up to batteries. At the top of the installation, light pours through cut-out stars onto a blue field, creating a restful shaded area.

Shelton’s specialty is tending to the ailing plants in the strawberry nursery. He’s got a life-giving touch; a thriving vegetable garden near the strawberries is a point of pride.

“It’s a wonderful project,” says Shelton, who takes the bus from his home near Inglewood to work at the flag six days a week. “I’ll be riding back and forth, telling people about it.”

Shelton does his job as part of the VA’s “compensated work therapy” program. So does Mel Williams, 59, an Air Force veteran who’s in charge of the onsite “vermiculture”—the process of using worms and their waste to create a compost tea that helps plants grow.

Williams has a two-hour commute to work each way from San Pedro, but you won’t hear any complaints.

“I love this,” he says. “I’m being enriched with a lot of things here. I wake up and look forward to it…It gives me time to ponder what’s next.”

“I love this,” he says. “I’m being enriched with a lot of things here. I wake up and look forward to it…It gives me time to ponder what’s next.”

Bon, who lives in Topanga Canyon, said she was moved to create Strawberry Flag after the election of Barack Obama created an “imperative for the rest of us to rise to the occasion.”

“It makes sense to redefine what it means to be a patriot,” she says, “by growing a strawberry flag in the midst of under purposed buildings in the center of historic West Los Angeles.”

The artist, granddaughter of Walter Annenberg and a trustee of the Annenberg Foundation, is known for other works including Not A Cornfield near Chinatown in downtown L.A., in which she transformed an “industrial brownfield” into a cornfield. She’s also currently at work on a film project about the Owens Valley called “Silver and Water.”

Her land-use agreement with the VA ends in September. But she hopes to see some kind of continuing presence on the site that will keep the spirit of Strawberry Flag alive after she leaves.

Since it started last June, the project has grown quickly and organically.

There’s a Strawberry Flag Internet radio station, with programs put together in the gleaming Airstream trailer (also reclaimed and recycled) that serves as an on-site office. (A neon sign on the side of the trailer reads: GRAB A MOP.) A monthly newspaper, the Strawberry Gazette, is about to come out with its fourth issue. Strawberry Flag’s YouTube channel features a video chronicle of the project’s evolution.

The nearby VA buildings are being touched by the project’s vitality, too.

“It was a very different place when we came here last year,” says Rochelle Fabb, the project manager. “It was like a cemetery.”

One of the buildings now houses the project’s light-filled and inviting kitchen space. It’s where vets like Ruth Harris, Gregory Gauthier and Julio Espino work with newly-hired chef Gabriella Salamon, a raw food and healthy eating specialist, to learn the ins and outs of working with food grown on the site.

On Tuesdays, the kitchen serves up a healthy lunch after a “boot camp” workout on the stationary bikes. Wednesday afternoons are devoted to “jam sessions”—turning the strawberries and other fruits into preserves that are now proudly arrayed on shelves in the kitchen. Tea is served weekdays at 3 p.m., with a special High Tea offered once a month. (The next one is scheduled for 4 p.m. on June 10. Check Strawberry Flag’s Facebook page to RSVP.)

In another nearby building, Larry Flaherty and Ray Rodgers preside over the print studio. Lining the table are vibrant silkscreen patterns that were transferred to T-shirts during a workshop. The studio also offers sessions in print-making and landscape painting to veterans, many of them first-time artists.

In another nearby building, Larry Flaherty and Ray Rodgers preside over the print studio. Lining the table are vibrant silkscreen patterns that were transferred to T-shirts during a workshop. The studio also offers sessions in print-making and landscape painting to veterans, many of them first-time artists.

“I thought it was magic when I saw what they could do with colors,” Flaherty says.

Rodgers points to their program’s “therapeutic value.” “I personally have gained people skills,” he says.

While Strawberry Flag is intended primarily for vets, it’s also open to the public, who are welcome to take part in any of the activities. (A map is here.)

On Monday, a Memorial Day drum circle is scheduled at the site from 7 p.m. to 8 p.m. to remember those who have served.

“If you have a drum, bring it,” Fabb says. If not, “we’ll have plenty of things here to bang.”

Sherin, the chief of mental health at the West Los Angeles VA campus who helped come up with the concept with “fellow Topangan” Bon, sees in Strawberry Flag a powerful metaphor for the veterans under his care.

“Strawberry plants provided a service. They were pulled out of the ground, retrieved and brought to this healing ground…The whole time this is happening, the veterans are doing the exact same thing—literally. Tending to [the strawberries] is quite a therapeutic experience.”

He, too, hopes that Strawberry Flag can live on in some form.

“”Innovative projects that engage the vets and involve a VA-community partnership are absolutely the wave of the future,” Sherin says. “I feel that our facility can capitalize on the innovative model, the raw energy at the ground level, and can continue along these lines with a project that continues many of these things in an enduring manner.”

For now, the flag is an attraction—and a curiosity—for many of those making their way around the sprawling VA grounds. And for those who work there, it’s an ongoing passion and commitment to a rich circle of interconnected lives.

“It’s about the strawberries,” says Williams, as he tends the worms that nourish the crop that makes the jam they serve to his fellow veterans at teatime. “We have to keep the strawberries healthy.”

Posted 5/27/10

A bold new look for summer

May 20, 2010

The Santa Monica beach skies were grey but L.A.’s iconic lifeguard towers were anything but.

And the cadre of casual beachgoers who happened upon the just-unveiled towers—newly painted in wild, psychedelic hues—got an eyeful Wednesday morning.

If their early reviews are any indication, the towers’ summer makeover has the makings of an international crowd-pleaser.

“It’s beautiful!” said Yves Bollotte, a visitor from Paris, directing his Gallic enthusiasm at one of the three towers on view near the Santa Monica Pier.

“It’s groovy,” said Joyce Attal, CEO of a New York City marketing firm, who’d just finished jogging. “It’s bringing the hippie days back to the beach.”

“I think the towers are spiffy, if that’s still a word,” said Mary Loucks, a teacher from Kern County who was keeping a close eye on her soaked but happy field trip class of second-graders.

“I like the color and pizzazz,” added homeless advocate Ron Hooks, of not-so-far-off Marina del Rey, as he stood astride a blue bike on the boardwalk chatting with a homeless man with a football who called himself R.U. Faster.

By summer’s end, hundreds of thousands of beachgoers are expected to see the towers, part of a giant “Summer of Color” public-art project that by early June will bestow a temporary new look on all 156 L.A. County lifeguard towers, from Palos Verdes to Malibu.

When the project is complete, towers along a 31-mile stretch will sprout colorful flowers, figures and abstracts. Even the ramps and pilings are getting the Day-Glo treatment for the project, which will be on display until October.

The $1.5 million privately-funded effort is the brainchild of Bernie and Ed Massey, founders of the L.A.-based non-profit arts and education group called Portraits of Hope. Their organization brings together thousands of hospital patients, school children and disabled people to collaborate on brightly painted public art. Earlier targets for the colorful treatment: a Beverly Hills oil well, New York taxicabs and even a blimp.

At Wednesday’s unveiling, in which grey plastic sheeting was stripped off the three towers for a slo-mo “reveal,” lifeguard officials said they were initially skeptical of the color explosion about to overpower their towers’ traditional Holland blue.

“We are a conservative bunch, and we weren’t totally sold on this project at first,” Mike Frazer, chief of the county’s lifeguards, admitted to the crowd.

Frank Bird, a director with the lifeguards’ union, said skeptics became converts by helping out with the painting sessions at the project’s Marina del Rey headquarters with students from the Braille Institute and from a Compton middle school at which many students had never seen the ocean before the trip. “Our guys are really on board now,” Bird said.

At the ceremony on the sands, Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky thanked his wife, Barbara, for persuading him to get the project rolling with the county because of her admiration for the Masseys’ work. Her lobbying paid off; Yaroslavsky’s office helped smooth the way with county agencies with jurisdiction at the beach, including the Beaches and Harbors Department and the Lifeguard Service.

The giant projects are a form of art therapy. Kids learn that their efforts can make a difference when they see their finished artwork displayed in very public places. About 8,000 volunteer artists, mostly children, took part in painting over 2,000 pre-cut plastic-coated panels in recent months that are now being bolted to the sides and roof of the lifeguard towers. (See our earlier story here.)

“These projects are all about kid power,” Bernie Massey said at the ceremony.

The art therapy concept appealed to French tourist Bollotte.

“It is therapy for us, too,” he noted.

Lindsay Hannah, a visiting artist from British Columbia who was swinging on the tall swing set at the beach playground near the tower, felt the same way. “I absolutely agree that art is therapeutic,” says Hannah. “It’s fantastic.”

Posted 5-19-2010

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink