Coasts & Mountains

How the public won a Malibu sand fight

June 7, 2011

It started last summer in Malibu with a fight between surf camps and led through a black market to a legislative mystery.

It started last summer in Malibu with a fight between surf camps and led through a black market to a legislative mystery.

But the long, strange trip that this year led Santos Kreimann to the discovery of a mistake that was costing Los Angeles County hundreds of thousands of dollars is now offering the intrepid director of the Department of Beaches and Harbors a possible long-term fix for this summer’s first pressing problem: how to keep the beach bathrooms open and clean.

County beach maintenance workers came under fire last week in one of the more publicized sidebars to the county’s ongoing budget challenges. Amid complaints about scaled-back cleaning schedules, late openings and locked doors at the county’s 52 beach restrooms, Supervisors Zev Yaroslavsky, Gloria Molina and Don Knabe called for alternatives.

The discussion generated headlines and local talk radio furor. On Tuesday, Kreimann presented the Board with a short-term plan to delay some hiring and maintenance and to use marina lease-option and lease-extension fees to open more bathrooms earlier and beef up summer cleaning crews.

Less widely-known, however, was the story behind the long-term proposal Kreimann hopes will help pay for not only the bathroom maintenance, but for other beach services going forward: a change in the county’s longstanding permitting system for recreational beach camps.

At issue, Kreimann says, is the way the county allocates beach space to the hundreds of interest groups that do business on the sand each year, including legions of surf camps and summer recreational programs that traditionally have received permits according to seniority.

For-profit programs are required to pay a small percentage of their gross receipts in exchange for the permits. That assessment, however, has been waived in past years for city-sponsored programs and non-profit organizations; they’ve paid only a modest administrative fee for the privilege of setting up shop on county beaches. “But there are non-profits, and there are non-profits,” says Kreimann. “Some of these camps charge like $600 a week.”

With public revenues dwindling, he says, those non-profit programs looked like an untapped source of revenue. But when Kreimann, who was appointed director in 2009, inquired about the issue, he was told by staffers who’ve since retired that the nonprofits couldn’t be charged because state law prohibited the county from assessing fees on youth groups.

Then last summer, he says, a surf camp in Malibu resurrected the beach permit question when its owner called to demand that an unpermitted rival be thrown off the sand. “The camp operators got into a physical altercation over allegations that one was operating illegally,” Kreimann says.

Allen King, co-owner of Aqua Surf camp, says the set-to was more like “harassment.” But he confirms that the dispute arose from the beach use permitting policy—in this case, the seniority system, not the fees.

As surf camps had proliferated in recent years, beach permits had become highly valuable, and anyone who had one was reluctant to relinquish it to make space for newcomers. When the City of Santa Monica, where King had operated for more than a decade, decided to decrease surf camp permits to reduce beach crowding, King says, he found it impossible to break into the county beach space.

“We tried to get a county permit, we wrote letters, but it was a closed system,” King says. “Whoever got one first would just hold onto it forever, and nothing moved.”

King’s solution: to cut a deal with a permitted surf camp. He says he offered to expand the business of Kanoa Aquatics, based in the South Bay, by setting up shop to the north, on Surfrider Beach in Malibu under Kanoa’s brand.

After a year, however, the relationship soured, according to both parties, and got downright ugly after King returned to Surfrider—without a permit—the next summer, setting up shop right next to the spot where Kanoa’s owner, Kip Jerger, was now operating on his own.

“I got a little personal,” Jerger acknowledges. “In a way I’m sorry but in a way I’m not. I was like, ‘You guys are like sharks coming in from the ocean.’”

King, meanwhile, says he was just “taking a stand” against an unfair permitting system, only to be confronted by his former colleague. “They were out there yelling, ‘You’re illegal! You’re not allowed to be here!’” King says. “You could have built a reality TV show around it, it was so dramatic. No one got into a fistfight, exactly, but someone did throw a rock at our tent, and we have witnesses.”

Kreimann of the beach department says that when the dispute landed on his desk, he felt compelled to revisit the permitting system. Clearly, beach use had to be limited, but the seniority system was creating problems of its own. Some 50 camps had been waiting years for a spot on one of the beaches, and existing permits had been issued and reissued “with no real safety standards.”

“Multiple people were subcontracting their permits,” he says. “A black market is a pretty good analogy.”

And, he learned, only about 30 of the 162 permit holders were paying a share of their gross receipts to the county because of the state legislation that supposedly prevented the county from charging nonprofits.

“So three or four months ago, I said to my staff person, Penelope Rodriguez, ‘Find that law.’ ”

She couldn’t.

Rodriguez, a program manager, says she quizzed colleagues and searched files and databases, but “we didn’t have the actual bill in any files and nobody remembered the year or the author or what group had introduced it.”

Finally, she says, she traced the confusion to a bill from the mid-1990s that had gotten through the legislature before the governor took issue with a provision that said youth groups not only shouldn’t be assessed like for-profit beach camps, but shouldn’t need the same liability coverage.

“It turned out that the law had been vetoed,” says Kreimann. “We should have been charging them all along.”

Kreimann says the faulty legal assumption was “an oversight” by otherwise hardworking employees, the last of whom retired earlier this year. “The actual law was right there in our file when we went back to check it, but they had misunderstood it. It was one of those things you discover when people leave and you get a new set of eyes.”

Since then, a plan to revamp the system and to set up a competitive selection process for summer permits, based on minimum standards set by the county lifeguards, has been working its way through a series of Beach Commission meetings. A workshop was held in early spring.

Jerger, who has had his beach permit for 14 years, says he understands the need to raise revenue—in fact, he works part-time for the county as a recurrent lifeguard. But he predicts a change in the system will let in more camps and worsen beach crowding, which, thanks to the stalled economy, is already at record levels. (According to the County Fire Department’s lifeguard division, attendance last year topped 68 million, nearly double the 38 million beachgoers counted in 2005-06.)

And levying a percentage of gross receipts on nonprofit recreational programs, he says, could force him to start charging the families of hundreds of disabled and needy children, to whom he’s been giving a break on tuition.

King, on the other hand, says he’s glad to ante up if it means getting a permit.

For his part, Kreimann says the assessment will not only add a measure of fairness and oversight to the beach camp landscape, but could net “in the neighborhood of $500,000 a year, conservatively.”

A recommendation is expected to come before the Board by the end of August. Kreimann says it’s too late for the plan to cover the estimated $372,000 it will cost to revamp the cleaning schedule for this year. But if consensus is reached, it could make the summer of 2012 more convenient and fragrant.

And any surplus could go toward Kreimann’s next plan for getting the most out of the county beaches: “A lot of our parking machines are down a lot of the time, and if we replace them, it could really increase revenue.”

Posted 6/7/11

Trailblazer makes his mark in Calabasas

March 31, 2011

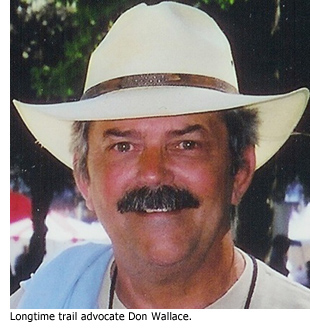

March was a banner month for Don Wallace. And not just because he and his wife, Jeanne, celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary.

March was a banner month for Don Wallace. And not just because he and his wife, Jeanne, celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary.

“We finished the party,” Wallace remembers, “and the very next afternoon, the phone rang.” With friends and family still filtering in and out of the Wallaces’ 4.5-acre ranchette in the Santa Monica Mountains, the longtime trail advocate let out a whoop as he received news for which he had waited most of his 70-year lifetime:

His beloved Las Virgenes Creek Trail had finally found its way under the Ventura Freeway.

“I was ecstatic,” Wallace says, still thrilled at the approval earlier this month of $300,000 in excess county bond funds that will allow the trail to run uninterrupted from the Santa Monica Mountains down through underpasses at the 101 and Agoura Road in Calabasas and on into Malibu Creek State Park.

The trail easement and improvements—officially dubbed “The Don Wallace Trail Project”—will not only connect the Santa Monica Mountains to the beach for people, horses and wildlife, but also honor one of the most zealous and hardworking trail advocates in Southern California.

For decades, Wallace and other activists have sought to create a path that would allow people and animals to follow Las Virgenes Creek from the pristine mountains down to the ocean, but their dream was stymied by development and traffic. Even as crucial tracts were acquired for the public, the 101 Freeway remained a dangerous concrete barrier between the mountain part of the trail and the beach part.

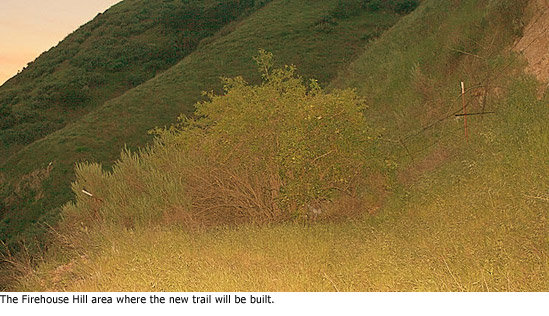

Then, last year, with funding allocated by Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, the Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority bought a key swath of wilderness known as Firehouse Hill from the developer Fred Sands. The nearly 200-acre Calabasas property is a gateway to the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area—and sits right next to the freeway.

Though environmentalists, activists and government officials cheered the acquisition for many reasons, trail advocates immediately saw its potential as an avenue through which they could bring the Las Virgenes Creek Trail—which is part of a larger loop called the Calabasas Cold Creek Trail—down to and under the 101 along a flood control easement, where it could then connect to the Malibu Creek State Park trail system. They’d just need to make the underpass safe and accessible.

The March vote provided that crucial support, opening the way for a 2,500-foot link that is expected to break ground next year.

“This is a wonderful victory,” said Wallace, crediting the many public agencies that pushed for the project. But Wallace’s friends and fellow advocates say there’s a reason the key link is being named after him.

“He’s one of the hardest working gentlemen I know,” says Stephanie Abronson, who edits the newsletter for Equestrian Trails Inc., Corral 36, a mountain equestrian group.

Born in Tennessee , Wallace moved to Van Nuys as a teenager after his father, a restaurant owner, visited relatives here and made it a goal to move to California . At 20, he married Jeanne, whom he’d met in a chemistry lab at Pierce College .

The couple settled in Canoga Park , had two sons and got into horseback riding, eventually deciding that they wanted enough land to have their own corral. Wallace, by now a Los Angeles city firefighter, found a spread near the unincorporated community of Monte Nido, and the couple built a house on it. They still live there with assorted horses, cats and dogs and a potbellied pig.

The couple settled in Canoga Park , had two sons and got into horseback riding, eventually deciding that they wanted enough land to have their own corral. Wallace, by now a Los Angeles city firefighter, found a spread near the unincorporated community of Monte Nido, and the couple built a house on it. They still live there with assorted horses, cats and dogs and a potbellied pig.

A trail ran near the Wallace’s acreage, and one day in the early 1970s, he says, a neighbor who wanted to build a winery came out with a bulldozer and blocked it in an attempt to keep passersby away.

“That trail had been put in in 1935 by the Boy Scouts,” says Wallace, who eventually forced the neighbor to open an alternative easement.

“It took three years of work and masses of paper, but I learned never to give up and never to say that it can’t be done.”

Since then, Wallace has served on the Santa Monica National Recreation Area Advisory Commission, the Resources Conservation District of the Santa Monica Mountains, the Malibu Creek Watershed Council and many other groups seeking to improve the mountains community.

He also served as a deputy for then-Supervisor Edmund D. Edelman in the early 1990s, and ran for supervisor himself in 1988 and 1994.

Throughout, when he wasn’t lobbying for trails or riding his horses on them, he was out clearing them with his bare hands, says Ruth Gerson, president of the Santa Monica Mountains Trail Council—“repairing tread, cutting back brush, reducing erosion, and encouraging others to work with him.”

That commitment has been challenged in recent years by health problems. Wallace says he has faced a stroke, vascular surgery and two bouts of prostate cancer since the 1990s; last year he underwent a triple bypass.

But his projects are far from finished—he’s already wondering how to restore the old Boy Scout trail behind his house.

“I walk every day,” says the trail blazer. “And I’m a very strong guy for 70.”

Posted 3/31/11

Beach’s elder statesman looks back

March 10, 2011

Edward Craig remembers waves so oil-polluted that he couldn’t swim without washing himself afterward with turpentine. He remembers beach crowds so environmentally careless that they blithely dumped their trash right onto the sand.

Edward Craig remembers waves so oil-polluted that he couldn’t swim without washing himself afterward with turpentine. He remembers beach crowds so environmentally careless that they blithely dumped their trash right onto the sand.

He remembers when surfers waxed their longboards with the paraffin their mothers used for canning. He remembers when women’s tank suits turned to bikinis and bikinis turned to thongs.

But ask the 70-year-old how many lives he has saved as Los Angeles County’s longest continuously serving lifeguard, and memory fails him. “Oh, my gosh,” he says. “Thousands.” Which makes sense, since Craig has been watching over local beach-goers every summer, without exception, for more than 50 years.

A retired teacher who for 38 years taught music in the Anaheim Union High School District, and who still supervises student teachers at Biola University, Craig has had a second career lifeguarding on weekends and summers since his late teens. County employment records show he was hired in May 1959 and has worked every summer since, including last summer. (One other recurrent lifeguard is older and has an earlier hire date, but records indicate that a medical issue sidelined him last year.)

“I’ve always liked the water,” says Craig, who grew up in Lennox and bicycled as a child down Imperial Boulevard to the ocean. “Riding on the waves as a body surfer, the ocean throwing you toward shore.”

Craig played water polo at Inglewood High School, El Camino College and Cal State Long Beach, and spent his childhood swimming and surfing in the South Bay. His favorite beach as a young man, he says, was the popular Manhattan Beach surf hangout known as El Porto; located near the Chevron oil refinery in El Segundo, its signature attraction is underwater—a deep fissure in the bay floor known as Redondo Canyon, which generates bigger-than-average waves on a consistent basis.

It also generates bigger-than-average crowds and bigger-than-average risks for swimmers—downsides that Craig would learn more about when, at 19, he became an ocean lifeguard. El Porto, which is still where he works most, ended up being his first professional post.

“On my first day on the job, I had 37 rescues,” Craig remembers. “People losing their boards, people stepping into rips. It was a pretty rough day.”

Does he remember the first swimmer he saved? “No,” he says, “but I do remember some amazing rescues over the years.”

There were the two exhausted swimmers he pushed for the length of three football fields on a surfboard to free them from a particularly vicious riptide.

There were the seven kids from Lawndale who ran full-tilt into the ocean, even though they could not swim and Craig had warned them to stay out of the water.

“I had two on the can, one by the hair, one in a cross-chest carry, one holding onto my foot, ” he remembers. “I was out there by myself—all the other guards were involved in other calls that day. Fortunately an older surfer came by and took the other two off my hands.”

Then there was the yellow Labrador who chased a stick into a riptide, leaving his anguished master ankle-deep in water, shouting the dog’s name helplessly at the waves. “The dog was way out there and really struggling—I could just see his nose barely sticking out of the ocean,” Craig remembers.

“I started swimming, wondering how in the world I was going to do this rescue. But when I swam up and I shoved my rescue can under his belly, he put his paws through the front handholds and they got stuck! I was able to drag him to shore, and the guy was so grateful, he came back to the tower with a case of beer the next day.”

Craig was glad, too: “I kept thinking, ‘What if I have to give this dog mouth-to-mouth?’”

Craig says the county’s beaches have changed substantially over the summers. For one thing, they are much cleaner and safer than they used to be.

“There was a lot more pollution. We’d often take a gallon of turpentine along to wash ourselves off after swimming. We’d paint each other down with a big paintbrush—you didn’t want to track that oil through your mom’s house. Also there was a lot of litter—you could look all up and down the beach and not see a trash can. And there was a lot more tar on the beach.”

Now, government regulation and environmental consciousness deter litterbugs and industrial polluters. “The beaches are meticulously cleaned,” Craig says. “We have four trash cans every hundred yards.”

And beach-goers are safer. Lifeguards are more professional, more numerous, better trained and stationed in lifeguard towers that are better equipped and closer together.

“Back in the ’60s, rescues were much longer distance because people would be pulled out farther,” Craig remembers. “Not because ocean conditions were different, but because there were so many fewer of us that by the time we got to them, they could be 50 yards offshore in a big boil. And there were no wave runners to help us out.”

Nor, for many years, was there much law enforcement, at least at El Porto. When Craig started, the beach was an unincorporated “county island” between Manhattan Beach and El Segundo. Packed end-to-end with little surf shacks arrayed along narrow alleys, El Porto was notorious in those early days for the bevies of airline stewardesses who bunked there and the surfers who populated its raucous bar scene. Until Manhattan Beach annexed the 34-acre area in 1980, the nearest authorities were 20 minutes inland at the sheriff’s Lennox substation, he says.

“We had one period in the mid-1970s where a group of armed Nazi surfers declared it their turf,” Craig remembers. “They’d throw things at people from the parking lot and shoot holes into the back of the lifeguard towers.” If someone at the beach was injured, he says, the paramedics of first resort were the lifeguards. Now, of course, El Porto is just another well-patrolled coastal neighborhood in sedate, pricey Manhattan Beach.

One thing that hasn’t changed much is the exceptional fitness required of county ocean lifeguards. Craig still vividly remembers his first lifeguard certification test.

“You swam around a buoy at the Hermosa Pier, and then south to the breakwater, then around another buoy and then back to the beach,” he recalls. “You did this in mid-April, so the water was still quite cold. It was a thousand-yard swim, not counting the 200 yards out and the 200 yards back in, and there were over 200 people, probably, the year I took the test.

“They took the top 25 across the line. I saw the mob going for the buoy and I thought, ‘Oh, my God.’ I was a decent swimmer, but it was daunting. The water was so cold, and the current so strong, and the wind so fierce that almost half the people had to be picked up or brought back in before they covered the first 200 yards.”

But Craig made it: “I was No. 11,” he remembers. “These things stick in your mind. “

Craig still takes the test every year, and still passes. “Obviously I’m not the fastest guy on the beach, but my average time is about 10 minutes, 30 seconds, depending on conditions,” he says.

His fitness regimen is not the average 70-year-old man’s daily workout. A 30-mile bike ride every Monday. An 80-lap swim on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday. Two-miles of wind sprints on the beach, twice weekly. A 3-to-5-mile row in a single-man Dory twice monthly. On-duty workouts daily. Oh, and he still surfs two or three times a month.

“He’s the perfect waterman—an elder statesman of lifeguarding,” says Section Chief Terry Yamamoto of the County Fire Department’s lifeguard division, who has known Craig for three decades, since Yamamoto was a teenager hanging out at El Porto and Craig was the summer lifeguard there. Craig, he says, was one of a handful of lifeguards who mentored him into the profession. Among other things, Yamamoto says, Craig taught him “how to stay calm in all situations.”

“The older you get, the wiser you get in this job,” says Yamamoto. “You can almost predict how people are going to behave on the beach. It becomes instinctual, so that you can be where you need to be almost before something happens.

“We’ve been on literally hundreds of rescues together, and because he’s been on the job for so long, Ed tends to be there as quickly as the younger guys because he knows where he’s going to be needed.”

Nonetheless, Craig says, “this year will probably be my last.”

“I’ve never lost a swimmer,” he says, “and I still feel I could make any rescue I could see. But I’m getting to the point now where you try to be realistic about your career.”

Retiring from the lifeguard tower would give him more time for his music, his wife of 46 years and his two granddaughters; it might also make for some slightly less stressful summers. “Ninety percent of the job is sheer boredom and ten percent is sheer terror,” jokes Craig.

Still, he says, “I don’t think I’ll ever get tired of watching the water—the pelicans flying by, the surf, the sailboats, the ships offloading their supplies. It never changes, and yet it’s always different, always moving. It’s one of the fascinating things about the sea.”

El Porto Lifeguard Station

Posted 2/16/11

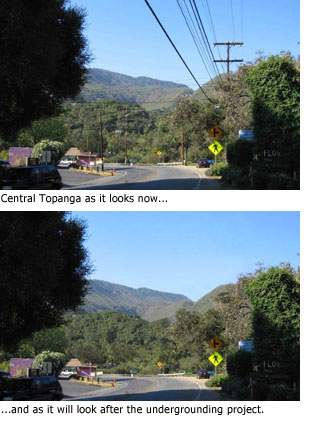

Erasing “wire blight” in Topanga

March 8, 2011

It isn’t the sexiest construction project in Los Angeles County. And it won’t be finished until 2014.

But to anyone acquainted with the hazards of fire season—or just the hazards of trying to find an unobstructed view in pretty-but-populous Southern California—the plans taking shape this month in Topanga eventually should offer a whole new perspective.

Next week, the county Department of Public Works and Southern California Edison representatives will launch a series of meetings to discuss the undergrounding of overhead utility lines in the rural community’s central business district around Topanga Canyon Boulevard and Old Topanga Canyon Road.

The $2.4 million project, which will be paid for by a statewide utility fee administered by Southern California Edison in L.A. County, will bury about a third of a mile’s worth of electricity, cable and phone lines that now clutter the view and present ongoing traffic and fire hazards along the right-of-way.

“The main goal is aesthetic, but there’s also a safety issue,” says Steve Dunn, a senior civil engineer at Public Works. Power poles along winding roads, such as Topanga’s, raise the risk of motor vehicle crashes. And in recent years, at least three massive Southern California brushfires have erupted as tree limbs and lashing utility lines have been blown into overhead power conductors by Santa Ana winds elsewhere in the region.

“The main goal is aesthetic, but there’s also a safety issue,” says Steve Dunn, a senior civil engineer at Public Works. Power poles along winding roads, such as Topanga’s, raise the risk of motor vehicle crashes. And in recent years, at least three massive Southern California brushfires have erupted as tree limbs and lashing utility lines have been blown into overhead power conductors by Santa Ana winds elsewhere in the region.

The project is one of many funded by the California Public Utility Commission’s so-called “Rule 20” program, which combats “wire blight” by helping communities and municipalities bury utility lines. Rule 20 regulates a utility’s recovery of the costs of undergrounding overhead electric equipment and gives local governments dibs on a share of a power company’s capital budget according to the number of rate-payers in each jurisdiction.

The annual amounts are not large—the average cost of an undergrounding project only adds about a nickel a month to the average residential customer’s electric bill, according to SCE—but over time, a municipality’s share can accumulate.

Unincorporated Los Angeles County’s allotment, for instance, amounts to about $3 million annually, which the County then splits among its five supervisorial districts.

The Topanga project will be funded by nearly two decades’ worth of the Third Supervisorial District’s allotment.

Other recent projects include a $4 million undergrounding project in an unincorporated area near Arcadia and a $10 million undergrounding and reconstruction project along 2.6 miles of Rosemead Boulevard.

This month’s meeting, Dunn says, will acquaint the community with the project and launch the environmental documentation. (And notify Topangans, incidentally, that construction is expected to take about 1½ years once it breaks ground in 2013.) The gathering is scheduled for 7 p.m. at the Topanga Elementary Charter School Auditorium.

Posted 3/8/11

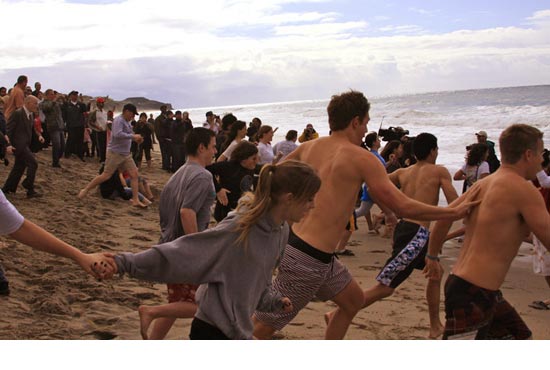

Plunge in for Special Olympics

February 24, 2011

Love the idea of splashing in frigid water for charity but hate traveling to an icy destination to do it? You’re in luck. Chill out at the Polar Plunge, jumping off this Saturday, Feb. 26, from two SoCal locations: Zuma Beach and Lake Castaic.

The Plunge benefits Special Olympics Southern California, whose programs help local children and adults with intellectual disabilities improve their self esteem and physical fitness. Sponsors include the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department, the Department of Beaches and Harbors, and county Lifeguards. Sheriff’s deputies and lifeguards will be on hand to participate and keep plungers safe.

You can register individually or as part of a team, and family and friends are welcome to cheer the plungers on. A minimum donation of $50 per individual is required to participate, which entitles you to a T-shirt, a chance at prizes, plenty of hot coffee and the knowledge that you have contributed to a good cause. If you want to show support without taking the plunge, simply donate to one of the teams.

Registration for the Zuma Beach Plunge begins at 8:30 a.m., and the plunge itself is at 10 a.m. A light breakfast will be served before the event, which will be hosted by Miss Malibu 2011. Lifeguards will perform a mock helicopter rescue, and KTLA anchor Glen Walter will announce the start of the plunge. UCLA’s Anderson School of Business and USC’s Marshall School of Business are bringing large groups. You can park for free on the west side of Pacific Coast Highway, or for $4.75 in the Zuma Beach lot.

Registration for the Castaic Lake Plunge begins at 8 a.m., and the plunge is at 10 a.m. (Be forewarned: Snow is forecast for the day of the event!) The Castaic Lions Club will provide a pancake breakfast from 9 a.m. to 10:30 a.m. Parking is free on Castaic Lake Road at the West Ramp entrance.

Veteran plungers recommend wearing something to protect your feet from the cold sand, and bringing towels and warm clothing for the chilly aftermath. You can plunge as deep and long as you want (within lifeguard safety guidelines), but keep your head above water so you can be spotted. Wacky costumes are welcome, and an award will be given at each location for the best one.

And if you decide to brave the February waters this weekend, why not share your photos on our website? Those who took part can savor the memory, and those who didn’t can shiver in solidarity.

Posted 2/24/11

The sandman cometh to Venice

October 12, 2010

On paper, it sounds almost boring: Move some sand across a beach. But when you’re talking about Venice Beach—L.A.’s seaside cradle of Beats and bodybuilders, celebrities and chainsaw jugglers—not even the sand wants to be ordinary.

So next month, engineers will be dodging just about everything from roosting birds to running grunions to random pipes and renegade sunbathers when the county’s long-awaited shore refurbishment gets underway.

The $1.66 million project, approved by the Board of Supervisors on Tuesday, will restore a section of beach around the landmark lifeguard headquarters that has been significantly eroded in recent years.

Since the construction of Venice’s breakwater in the early 1900s, the coast has been susceptible to erosion because the sand can’t be replenished by natural wave action. Over the decades, sections of beach have been periodically nourished, although fresh sand has not been added since the 1970s.

But the winter storms of 2004 and 2005 left the beach particularly damaged, and the wind and waves chewed it up again last winter. As a result, the renowned attraction was reduced to a dispiriting shadow of its famous old self, and local beachgoers couldn’t help but mourn the estimated 30,000 cubic feet of sand that disappeared.

The refurbishment will restore a segment of beach about the size of two city blocks where the public parking lot, recreational facilities and lifeguard headquarters are located.

“At first glance, it’s a very simple project,” said Department of Public Works Project Manager Sam Shadab. “But the devil is in the details.”

Dry sand will be hauled a half-mile or so into the eroded area from a 2,500-foot-long stretch of better-stocked beaches north of the breakwater. A convoy of massive earth-moving equipment will scoop two or three feet of surplus sand from the “borrow” area’s surface, then transport it in 10- or 20-cubic-yard loads to the eroded area.

Each borrow site, Shadab said, will be barricaded with safety fencing to protect the public from construction activity. Public access to the water will be limited during construction to small openings in the barricades every 150 feet or so.

Each borrow site, Shadab said, will be barricaded with safety fencing to protect the public from construction activity. Public access to the water will be limited during construction to small openings in the barricades every 150 feet or so.

Each load, Shadab said, will be spread over the new site to smooth the beach and cover the exposed stone facing in front of the lifeguard building. The project should take only six to eight weeks, he added – a good thing “because we have a very small window of time.”

Why the limitations? Shadab and Public Works Section Head Kamel Youssef chuckle as they tick off the complications engineers will face.

“Well, we cannot operate the equipment on nights or weekends,” explained Youssef, who is overseeing the project. “And we cannot have construction from May to September, because that is beach season.”

“Then,” Shadab added, “we have the roosting season of the Snowy Plover. And we have to avoid the running of those little fish that look like snakes – the grunion. And we have to be cognizant of the California Brown Pelican and the California Least Tern, and make sure they have not returned late in the season.”

And then there’s the human wildlife, Youssef added.

“Some of this equipment weighs 20 tons with a 20 cubic yard capacity and a cockpit 10 or 12 feet off the ground,” he noted. “The wheels are as big as a man. The operators cannot see everything like you can see in your vehicle. So we have to have an extensive and detailed security system, and pilot cars in front of the convoy so that people don’t get run over. Some people, as you know, sleep in the sand.”

Then there’s the 66-inch drainage pipe that movers will have to avoid crushing, a challenge engineers plan to meet with a temporary “bridge” of reinforced concrete. And yet, Youssef and Shadab said, the strategy is still cheaper and less complicated than hauling in inland sand that might have damaged roads in other municipalities, widened the project’s carbon footprint and threatened the beach’s ecosystem.

The project, Youssef said, should be completed in January – one last obstacle permitting.

“If we have a lot of storms and rain,” he noted, “the equipment might sink into the sand.”

Posted 10/12/10

Malibu’s worthiest of waves

October 7, 2010

It has starred in more than 75 movies. It is the namesake for one of California’s best known environmental groups. And its “original perfect wave” has made Malibu a Mecca for generations of surfers.

Now Surfrider Beach—the birthplace of modern surfing in California—will add yet another accolade to its long list of laurels: On Saturday, it will officially be dedicated as the nation’s first World Surfing Reserve.

“These special surf spots are the Yosemites of the coast,” said Dean LaTourrette, executive director of Save The Waves Coalition, a non-profit environmental organization based in Santa Cruz County that has spearheaded the international initiative to designate and preserve iconic surfing coastlines worldwide.

“People need to understand how valuable and fragile they are, and the World Surfing Reserve designation will help the international and local communities focus on protecting them.”

Although the World Surfing Reserves designation is purely honorary and will have no regulatory authority or impact, LaTourrette said the groups involved hope it will raise awareness. The designation, modeled after a successful Australian program that has singled out more than a half-dozen of that continent’s beaches, was inspired, he said, by UNESCO’s World Heritage Sites, which help preserve locations of cultural significance.

The Malibu reserve, he said, will be the first in a series of World Surfing Reserves—“a UNESCO of surfing”—planned for pristine coastlines in Australia, Hawaii and other important surf destinations.

Surfrider Beach, formally known as Malibu Lagoon State Beach, lies near the Malibu Pier on the northern arm of Santa Monica Bay. Although it has been plagued over the years by crowds and water quality issues, its long, smooth-breaking waves are considered the “definitive California pointbreak,” according to “The Encyclopedia of Surfing” by former Surfer magazine editor Matt Warshaw.

Surfrider beat out more than 125 nominees for the inaugural designation, including Trestles, Mavericks, Waikiki, Manly Beach in Australia and breaks in Indonesia and Europe. The choice, LaTourrette said, was based in part on the long fight surfers have waged to help keep it clean.

Situated at the mouth of the Malibu Creek watershed and Malibu Lagoon, Surfrider’s history has been entwined with the environmental movement since the late 1960s, when runoff began fouling the lagoon with waste and sewage. In fact, the Surfrider Foundation, one of the state’s most dogged environmental groups, was founded as a response to Malibu’s environmental issues.

The World Surfing Reserve designation “is a statement by the global surfing community that Malibu is extremely important to surfing and should be protected,” said Chad Nelsen, the Surfrider Foundation’s environmental director.

“Of course, WSR do not have any legally binding protection, so the real value of the WSR will be demonstrated by local and global support for the protection of Malibu.”

In recent years, a number of public and private sector initiatives have been undertaken to reduce the pollution that has long plagued the waters of Surfrider—the most recent being Malibu’s newly opened Legacy Park.

Beneath the $38-million project is a network of pipes and filters designed to remove bacteria and contaminants from stormwater runoff in Malibu Lagoon, Malibu Creek and Surfrider. Among the governments donors was L.A. County, which contributed $700,000. Private donors included Rita Wilson and Tom Hanks, Don Henley, Rob and Michele Reiner, the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation and the Marilyn and Jeffrey Katzenberg Family Foundation.

As part of the surfing reserve designation, a local stewardship council has been created to help coordinate and publicize Surfrider’s various preservation efforts. Members so far include such local surfing legends as Allen Sarlo, Andy Lyon and Steven Lippman, community leaders such as Michal Blum of the Malibu Surfing Association and Jefferson “Zuma Jay” Wagner, the wave-riding mayor of Malibu.

“We’re the local ones who will keep an eye on it,” said Wagner, adding that the designation will be invaluable as a fundraising and advocacy tool.

“The social stigma of messing with a preserve may not be much to a lawyer, but, boy, to the general public, that’s a battle cry.”

The dedication on October 9 will begin with a sunrise ceremony on the beach and a blessing by local Chumash leader Mati Waiya, followed by a paddle-out, a formal dedication at 11 a.m. and an evening celebration at Duke’s Malibu.

California Coastal Commissioner Ross Mirkarimi said the commission has already adopted a resolution supporting the World Surfing Reserves program, which he said “will benefit not only surfers, but also the greater coastal community.”

Posted 10/07/10

Take a glide on the wild side

September 21, 2010

Unless you happen to be a bird, chances are you’ve never seen the Santa Monica Mountains quite like this.

An intrepid team has embarked on an aerial project to capture the mountains’ majesty in high-definition footage shot by a camera mounted on an XT-912 hang glider from Australia.

Eventually, the stunning aerials—recently edited into a soaring snippet posted on YouTube—will become a central visual attraction in a new visitors’ center to be built starting in December at the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area. The footage also will be provided to the Sierra Club, woven into an episode of the Trailmasters series shown on cable and public television and, under a plan still being developed, may become part of a new National Parks display at LAX.

For now, though, it’s a work in progress, and, for the guys in the air, a thrill a minute.

Even a 5 mph breeze can buffet the low-flying 1,000-pound craft, which holds a pilot and a camera operator and not much else.

“It bounces you all around the place and it creates extreme turbulence. You could get blown right into the mountain,” says Jeff Messenger, a licensed pilot whose company, Hi Def From Above, focuses on specialized camera work.

Messenger, along with his partner and cameraman Roger Mason, has taken the craft up a number of times in recent weeks, flying for hours to squeeze out precious minutes of usable footage.

Messenger, along with his partner and cameraman Roger Mason, has taken the craft up a number of times in recent weeks, flying for hours to squeeze out precious minutes of usable footage.

Why do it? “Passion—and my love for open space,” Messenger says. “Just to share it. I’ve never been so impressed with it as when I fly over it.”

Toby Keeler, a media specialist who produces the Trailmasters series, recently pulled together the 86-second rough cut, which offers a stimulating demonstration of what the final product will look like. (Be sure to adjust the picture to 720p to get the full HD experience.) Keeler’s efforts are being funded with grants from Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s office, the city of Calabasas and the Santa Monica Mountains Fund.

Then there are the other kinds of contributions—like the one from Keeler’s award-winning composer neighbor, Randy Miller, who allowed him to use his “Heartland Images” as a soundtrack for the 90-second rough cut.

“While I’m not an avid hiker per se, I know the value this park has. I know the uniqueness. People don’t realize this is the largest urban national park in America, and it’s right in our backyard,” Keeler says. “It’s a point of view that no one ever sees.”

That includes park aficionados like Woody Smeck, superintendent of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area.

“This is the first time that we’ve had this kind of aerial footage. It’s just a spectacular point of view. You literally fly through canyons,” Smeck says. “The image that I like the most is when he’s sweeping down along the coastline…It’s like coming down from heaven.”

Posted 9/21/10

An L.A. beachcomber heads south

September 7, 2010

Los Angeles County’s sandprint will soon be showing up on oily Gulf Coast beaches.

At the urgent request of BP, the county’s Department of Beaches & Harbors is finalizing a deal to send a BeachTech 2000 to Mississippi to help in the cleanup of the Gulf oil spill. The two-ton “sanitizer” ordinarily rakes and sifts cans, bottles and cigarette butts from county beaches near Redondo. Now it will see action sifting tar balls from barrier island beaches blackened by the giant oil disaster.

“We thought it was a great opportunity for the county to get involved and assist in the clean up,” said Ken Foreman, assistant chief of facilities and maintenance for Beaches & Harbors.

In exchange for the three-year-old unit, BP will buy the county a new replacement, valued at about $50,000. The Board of Supervisors unanimously approved a motion by Supervisor Don Knabe at Tuesday’s meeting to seal the deal. The new unit should arrive next month.

The unusual trade came because BeachTech couldn’t supply the sanitizers quickly enough for BP, explained Scott Merrill, manager of BeachTech’s North American operations.

BeachTech’s models work particularly well because, unlike other beach groomers, their rakes can be removed and sand can be sifted exclusively through a screen, Merrill said. Raking breaks up the globules of oil, making cleanup more difficult.

Earlier this summer BP bought 25 BeachTech sanitizers after federal and state environmental officials determined that the equipment was effective. By late August, BP wanted 10 more, but BeachTech didn’t have the inventory to fill the whole order.

Earlier this summer BP bought 25 BeachTech sanitizers after federal and state environmental officials determined that the equipment was effective. By late August, BP wanted 10 more, but BeachTech didn’t have the inventory to fill the whole order.

Widely criticized for not reacting to the disaster swiftly enough, BP did not want to wait and asked BeachTech to call its best customers for loaners in perfect working condition.

“They said, ‘We don’t want cash for clunkers’,” Merrill said.

Besides L.A. County, four municipalities (three in Florida and one in Alabama) also agreed to send equipment. Clean up crews are using the equipment mostly at night and in the cool early morning hours, when the oily gunk is coolest, hardest and easiest to handle.

L.A. County’s yellow unit will be loaded on a truck later this week, most likely bound for unpopulated barrier islands off the Mississippi coast, where the beach cleanup is just getting underway. Foreman said that until L.A.’s new unit arrives, beach-cleaning crews will use other equipment.

“We should be okay for the time being,” Foreman said. “We didn’t want to miss the opportunity to help.”

Posted 9-7-10

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink