Hospitals & Clinics

Future of Olive View TB ward in doubt

June 15, 2010

Los Angeles County is spending more than $16 million to build a dedicated tuberculosis ward that also could serve as a treatment center to isolate victims of a bioterrorism attack.

But something’s missing: people to staff it.

With construction on the ward almost done and an opening to the public possible by January, 2011, there’s been no appropriation of the $2.4 million it would take to operate the facility in its first six months. The project is part of the effort to build a new emergency room at Olive View-UCLA Medical Center, at an overall cost of $53.2 million.

A lot has changed since the project to build the ward was launched in 2004. Tuberculosis cases have continued a steady decline while money’s gotten a lot tighter, with the county Department of Health Services now facing a $400 million deficit in the coming fiscal year.

The health department did not include a request to staff the unit as part of its 2010-2011 budget proposal “because of the fiscal issues at the moment,” said the department’s interim director, John F. Schunhoff.

Still, two supervisors—Zev Yaroslavsky and Michael D. Antonovich—have indicated they want to make sure there is funding to get the unit up and running when final changes to the county budget are made in September. Both Supervisors have advocated for full funding by including the TB ward’s staffing in their “unmet needs” lists submitted as part of the budget process. (For all the supervisors’ full lists, click here and scroll down.)

Unless funding is found, the 15 new Olive View isolation rooms will likely sit idle. That, in turn, could place pressure on hospitals elsewhere in the system, which must provide bed space to some infectious TB patients until they are medically cleared to leave.

Consolidating TB care in one facility would be an efficient way to make day-in, day-out use of a facility that would have an important mission during a disaster like an anthrax attack, said Carolyn Rhee, chief executive officer of the county’s ValleyCare Healthcare Network, which includes Olive View. The ward also would free up isolation beds at other county facilities for patients who need them.

The county hospital system currently has 295 isolation rooms—in which negative air pressure keeps infectious airborne particles from spreading beyond their walls.

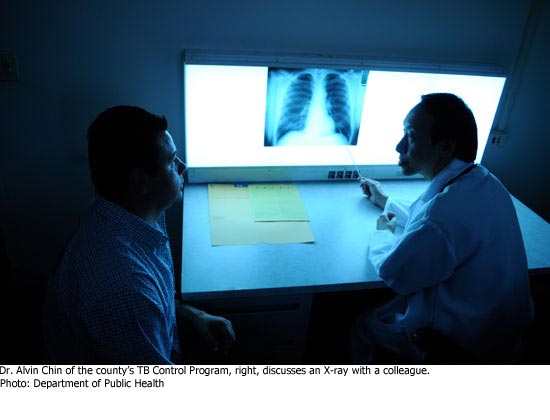

Schunhoff noted that a dedicated facility could offer better care to TB patients because of its specialized nature. However, facilities to treat the disease—once widely feared and commonly known as consumption—have become increasingly rare, as noted in this recent New York Times article about a Florida facility that is the last of the country’s original TB sanitariums.

Los Angeles County lost its only dedicated tuberculosis ward when High Desert Hospital in Lancaster closed to inpatients in 2003. Olive View itself started off as the county’s tuberculosis sanitarium when it first opened in 1920.

But times have changed. In a June 7 letter to supervisors, County Chief Executive Officer William T Fujioka said the years-long decline in TB cases means that the number of patients eligible to be transferred to the new Olive View facility, which would have a capacity for 30, “is calculated to be as low as 6 and rarely more than 12.” The letter estimated that the county would receive some reimbursement from Medi-Cal or Medicare for treating a majority of the patients but said that would not be enough to offset the costs of operating the facility.

Tuberculosis, which preys on people with weakened immune systems, was on the rise during the worst years of the HIV epidemic, hitting a peak of 2,198 cases in Los Angeles County in 1992. As the HIV crisis was brought under control, TB steadily declined, with 706 cases reported countywide last year.

Public health officials say that’s good news—but no reason to be less vigilant about a disease that infects one-third of the world’s population and kills nearly two million people a year.

Public health officials say that’s good news—but no reason to be less vigilant about a disease that infects one-third of the world’s population and kills nearly two million people a year.

“When I trained at County Hospital in the ‘80s [when the AIDS epidemic was raging] people died left and right, like flies,” said Dr. Rashmi Jan Singh, assistant director of the county’s Tuberculosis Control Program.

“It’s still around, and just waiting for opportune conditions to create problems.”

So vigorous efforts are needed to keep TB in check, including making sure that patients continue treatment long enough to get well and avoid infecting others.

That can be a challenge, particularly when dealing with homeless people with substance abuse problems, who are among those likely to contract TB in Los Angeles.

“It’s really complex,” Singh said. “Patients take off to use drugs, to use alcohol. We have to bring them back.”

The disease is curable, but patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis must remain isolated until they are no longer infectious—which can present a problem both for the public health workers trying to make sure they take their medicine and get well, and for the hospitals that need that bed space for acutely ill patients.

Most hospitalized TB patients can leave the hospital once the acute phase of their treatment is concluded, and finish taking their medicine at home. But that’s not an option for some, including the homeless and those who live with small children and people with compromised immunized systems, like those with HIV and diabetes, who are most vulnerable to the disease. For them, an extended hospital stay is often unavoidable.

And even now, with effective treatments available, the disease can take a devastating toll.

“Its social impact is sometimes incredible,” Singh said, recalling a case in which a 28-year-old woman who hadn’t acted on her symptoms early enough died after spending weeks in intensive care at Olive View. The woman’s 10-month-old baby was infected as well, but survived and is still being treated.

“It devastated this family,” Singh said.

So from Singh’s vantage point, a dedicated TB ward at Olive View would be an invaluable weapon in an ongoing war.

“For us, as TB control,” she said, “it would be a great thing.”

Posted 6/15/10

Fighting for the disease-fighters

April 20, 2010

Out there on the front lines of the war on contagious disease in Los Angeles, the 14 centers run by the county’s Department of Public Health have seen it all—from hepatitis A to tuberculosis.

Now the centers—which log about 280,000 visits a year—need some medicine of their own.

The new proposed county budget calls for a sweeping “regionalization plan” that would improve the bottom line for the deficit-plagued public health department, but would also lead to the consolidation or even elimination of services in many centers.

Seeking to buy some time—and perhaps ease the pain of budget-driven service cuts—the Board of Supervisors on Tuesday approved two motions seeking funding relief for the department as the county’s budget process moves forward.

Supervisors Zev Yaroslavsky and Don Knabe noted that the proposed budget submitted by Chief Executive Officer William T Fujioka already sets aside $3 million in reserve funds for use by the department, whose deficit is expected to hit $21.2 million in the coming fiscal year. But in their motion the supervisors said that $1.7 million more may be needed to preserve jobs and allow DPH a year to come up with an efficiency plan that does not jeopardize its mission to protect the public health. The motion directs the CEO and department to closely monitor this year’s DPH budget and to allow the $1.7 million carryover from any funds remaining when the new budget is finalized.

In a related motion, Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas asked the department and the CEO to provide before-and-after maps showing the “volume and accessibility” of public health services now and what they would be after the proposed cutbacks. He also asked the CEO to explore whether other outside funding sources could be found to help maintain service levels.

As things stand now, the department is looking at as many as 75 layoffs—out of an estimated 131 countywide. It also is facing cutbacks under the budget-driven plan to consolidate services at some centers while eliminating a number of key clinical functions altogether at its Hollywood/Wilshire and Torrance health centers.

The centers’ mission is to provide treatment and testing for TB and sexually-transmitted diseases as well as care in the broad category of “communicable disease triage.” They also offer immunizations. In addition, the centers are the launching point for the county’s public health field staff, which takes the fight against contagious disease out onto the streets and into restaurants and other workplaces—anywhere an infected person may have come into contact with others.

.

After the board meeting, Jonathan E. Freedman, chief deputy director of the Department of Public Health, said he was cautiously optimistic about the coming year but noted there was little financial wiggle room, given the challenging budget picture.

“We have a delicately balanced budget here with very little revenue-generating possibility,” Freedman said.

The supervisors’ public health motions were among 10 offered Tuesday, asking the CEO to report back to the board on a variety of topics as budget deliberations get underway. Public hearings on the $22.7 billion budget are set to begin May 12, with budget deliberations set to start June 7.

Posted 4-20-10

An artful setting for an urgent mission

March 10, 2010

When artists meet with mental health clients to get a sense of how a psychiatric urgent care center should look and feel, the clients don’t hold back.

“Don’t use any really bright colors—and definitely don’t use any red.”

“Being in nature makes us calm down and feel good.”

And that institutional grey metal file cabinet over there? “That is exactly what we don’t want to see.”

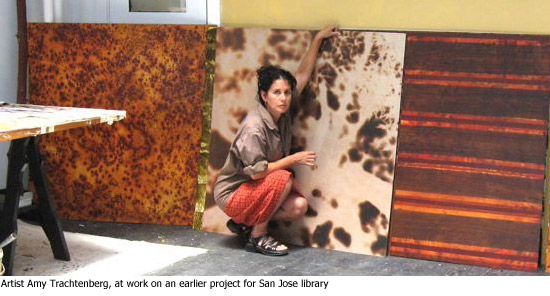

For artists Amy Trachtenberg and Jeffrey Miller, those conversations were a welcome validation of many of their ideas on color, nature, material and mood.

They also form an essential element in an extraordinary collaboration that will begin to take shape later this month when construction begins in Sylmar on the new facility, with the proposed name the Olive View Community Urgent Care Center.

Not so long ago, the aesthetics associated with mental health facilities were at best coldly clinical, at worst something out of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

The Olive View project aims to make a sharp break with all that.

The Mission-style project, which breaks ground on March 17, is the culmination of years of work by a county team that has made art and design central to its exploration of how the look and feel of the new building itself can play a role in the treatment of patients in psychological distress.

From color palette to carpet pattern, no detail has been too small for the county team working with the artists and architects HMC and gkkworks. The multifaceted working group includes representatives from the departments of mental health and public works, the arts commission and deputies from the offices of Supervisors Zev Yaroslavsky and Michael D. Antonovich. (A 2004 motion by Yaroslavsky, followed by another motion he authored with Antonovich a few weeks later, got things rolling on bringing psychiatric urgent care to an underserved area.)

The new facility is part of a larger movement to bring high-quality art into hospitals and other health care facilities not just as decoration, but to help in the treatment process.

Diane Brown, the founder of RxArt, a New York nonprofit that specializes in bringing contemporary art into medical settings across the country, says that hospitals were wary when they started nearly 10 years ago.

“When we did our first project, we had a hard time getting our foot in the door,” Brown says. “It was free, museum-quality art, and we couldn’t give this stuff away…Now hospitals call us up. We don’t have to beg anybody.”

RxArt, which is planning to place a Jeff Koons installation in the CAT scan room of a children’s hospital in Chicago, has worked on an inpatient psychiatric ward and has an upcoming mental health urgent care project of its own coming up, at New York’s Kings County Hospital.

“You have to be so careful with what you’re putting in,” Brown says of such projects. “Something I thought was perfect was just completely inappropriate.”

On the opposite coast, such considerations are front and center during a meeting to determine tile, paint and flooring choices for the new Olive View urgent care. A certain shade of green draws comments like “I’m thinking psychiatric hospital circa-1965 throwback.”

At the same meeting, someone asks whether blue should be ruled out as a “depressive” color.

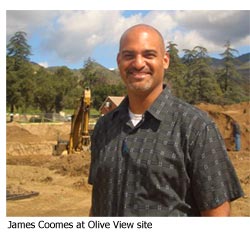

James Coomes, the mental health department’s program head for Olive View urgent care, quickly responds to that one, saying that in this kind of treatment setting, “it’s really the bright red that we were concerned about. If someone’s agitated, we want to bring them down.”

Such nuances are crucial when you’re creating a space for the relatively new concept of mental health urgent care. The facility must serve patients too troubled to wait weeks for a simple counseling session but who may not need full-on psychiatric emergency room treatment. Clients could be people experiencing the onset of schizophrenia, a serious bout of depression, or a traumatic event. Many, if not most, have substance abuse problems as well.

“We can decompress the psychiatric ER [at Olive View-UCLA Medical Center] if we do our job right,” Coomes says.

Even without a permanent home, the county’s mental health urgent care operation in the San Fernando Valley has been seeing a growing caseload: from 832 cases in 2006 to 1,570 cases last year.

One of those clients, William O’Reilly, says the urgent care staff threw him a lifeline when he was in the throes of a profound depression.

“That place saved my life,” says O’Reilly, 47. “There was so much compassion shown…That’s fantastic that there’s going to be a new facility.” When the new urgent care opens, the county aims to treat more than 3,000 clients a year there.

The input from clients—part of a day-long tour for the artists–came from residents at the county’s Hillview intensive residential center, for homeless people who have received mental health treatment.

“This was really quite a wonderful thing for us,” Trachtenberg says. “We got to learn the kinds of things they are drawn to and what repels them.”

The artists—who are a married couple as well as professional partners on this project—say they drew on a wide range of influences, from Ayurvedic medicine to “sacred geometry” and classical allusions, to create the Olive View plan.

“Our goal is to try to create a kind of calming, restorative place,” Trachtenberg says. “We really drew from various cultures…timeless forms, ancient forms, a response to nature and to geometry—an approach both ornamental and restorative that hopefully will lift the spirit.”

“The staff was important, too,” says Miller, who is also a landscape architect. “They were making sure we were aware of certain color relationships.”

While psychiatric urgent care is offered elsewhere in the county, including St. John’s Hospital in Santa Monica and the Augustus F. Hawkins Mental Health Center in South Los Angeles, Olive View will be the first stand-alone facility to be built specifically for that purpose.

The $10.8 million, 10,800-square-foot project—which aims for LEED silver certification for its environmentally sensitive building practices—is also the first in the county to incorporate the artists’ concepts in the plan from the very beginning of the process.

The $10.8 million, 10,800-square-foot project—which aims for LEED silver certification for its environmentally sensitive building practices—is also the first in the county to incorporate the artists’ concepts in the plan from the very beginning of the process.

“It’s really been great having this team effort—not just coming in after the fact and plunking in some art,” says Carrie Brown, a civic art project manager for the county Arts Commission who has been working on the Olive View project for the past three years.

Integrating art into new projects took off with the enactment of the county’s civic art policy in 2004. Since the 2005-2006 fiscal year, 1% of the design and construction budget for capital projects must be allocated to art in and around the new developments.

When it came to selecting the artists for Olive View, the San Francisco-based Trachtenberg and Miller drew high marks for their experience. They’ve previously worked on projects including an atrium at Children’s Hospital in Oakland and a multi-faceted art installation for the rotunda of the Hillview Library in San Jose. Trachtenberg also served as the sole visual artist on a mayoral advisory panel for the suicide barrier on the Golden Gate Bridge.

But in the end, it was their artistic approach as much as their track record that won over the staff at the department of mental health.

In fact, mental health staffers were amazed when they first saw the interlocking circles motif incorporated into the project’s signature stepping stones.

Had the artists gotten a look at their treatment playbook?

The design looked like a direct homage to the “family systems theory” pattern at the heart of their therapeutic model—in which patients are linked with family and other support sources.

“They were sure that we had studied their diagrams,” Trachtenberg says.

Work on the Olive View art elements—which, in addition to the stepping stones, will include a painted frieze on wood panels, suspended sculpture, and a 49-foot “horizon sliver” composed of polycarbonate panels—is set to begin this summer. Trachtenberg and Miller are planning to install their work right after construction finishes in the summer of 2011.

The new facility can’t open soon enough for the staffers who will work there.

It’s been five years now since the phalanx of psychiatrists, social workers and nurses, caseworkers and community workers attached to the urgent care program squeezed into “temporary” borrowed space at the San Fernando Mental Health Center. That has meant five years of working in “submarine-like conditions,” often with little privacy as they seek to diagnose, treat and refer desperately troubled clients.

“This is stolen space. Actually, more begged and borrowed space,” Coomes says on a tour of the facility, introducing a small team of case managers and community workers charged with staying in touch with clients and making sure they are scheduled for follow-up visits.

The group’s supervising psychiatrist, Dr. Jeffrey Marsh, recently gave up his office to a junior colleague who sees more patients than he does. Marsh has a cubicle now. As for ambiance, well, it’s safe to say that a high point may be the Sigmund Freud action figure he’s put up on the wall.

Working conditions aside, what’s most important to Coomes, Marsh and their colleagues is being able to offer clients—and their families—a tranquil and healing environment to come to at a frightening and stressful time.

“To create an atmosphere that’s safe, calm and pleasant is really important for the population,” Marsh says. “There aren’t a lot of places like that.”

Posted 3/10/10

Taking the temperature at MLK

November 19, 2009

No one will feel the impact more keenly of the deal between Los Angeles County and the University of California than the patients of Martin Luther King Jr. hospital.

Patients and family members interviewed there Thursday shared high hopes that the partnership to operate the 40-year-old hospital complex in Watts will dramatically improve and expand medical services to the South L.A. communities it was built to serve.

Most thought that UC physicians enjoyed a high reputation and expect staffing levels to improve. Patients also hope that the new operators will move quickly to reopen shuttered hospital services such as the emergency room and expand specialty medical care to cut wait times and improve service.

Today’s UC vote brought a holiday spirit to the beleaguered medical facility. Second District Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas hosted a raucous lunchtime celebration in the hospital’s auditorium with patients, community members, hospital staffers and union officials. Many were sporting stickers reading “Open a New MLK Hospital. We are ready to partner.”

Even patients who didn’t know about the new agreement were optimistic. “I think it’ll be great,” said Marco Godoy, 42, of Norwalk, visiting the Urgent Care clinic with his son Andrew, 21, who’d injured his foot. “This hospital has had a reputation for not being well run. With the leadership coming in from the UC, I think service can only go up.”

Many patients expect a more streamlined and effective administration. Timothy Bingham, 62, believes that the old regime’s major shortcoming wasn’t ineffective medical care. The real problems, he argues, were caused by administrators who “operated and manipulated” the hospital as a jobs program rather than as a health-care provider.

“This is a nice facility, and the community deserves that it be well run for everyone’s benefit,” said Bingham, a retired schoolteacher who was receiving dental care at the hospital on Thursday.

Security guard Markus Cook said he also looked forward to a new day of improved administration and medical care for Watts and all of South Los Angeles County. “I would expect the UC to do a better job running the hospital,” said Cook, who retired from the Los Angeles Housing Authority and was keeping an eye on a remote parking lot Wednesday. “They have a better reputation and they’ll want to protect it.”

Still, a few patients had reservations about the advent of the UC regime.

“I’d rather not see them come in,” complained Tony Allen, 77, who said was happy with MLK hospital services before the closure. He’s afraid UC medical personnel will be “elite…prima donnas” culturally unable to connect with the hospital’s working class patients. “They wouldn’t know how to act with the community,” said Allen, a musician who leads the Watts 103rd Street Band and sat ramrod straight as he waited to obtain heart medication. Calling his doctor “the best,” Allen said he doesn’t want to lose him in the changeover.

Despite such misgivings, hopes are high that the chaos of recent years is nearing an end. Said Jeanetta Shamburger, who was visiting the internal medicine clinic for a checkup: “I expect to see more doctors here, and I think there’ll be less pressure on them” as they strive to deliver good medicine in an area that needs and deserves it.

MLK hospital: “Like a Phoenix rising” *

November 19, 2009

The University of California regents voted today to join forces with Los Angeles County to create a new hospital at the site of Martin Luther King Jr.-Harbor Medical Center—a signal of hope, innovation and commitment rising from one of the nation’s most distressing health care failures.

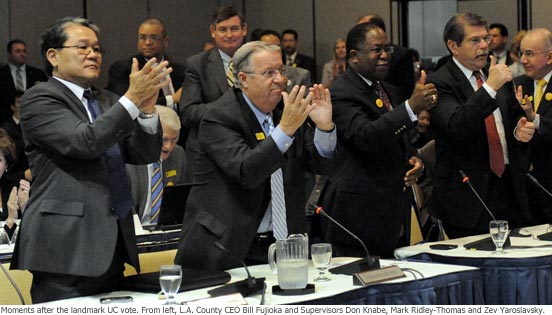

The unanimous vote, which came moments after the regents’ health services committee approved the plan, creates a partnership widely hailed as a potential national model.

“This is like a Phoenix rising in the heart of South Los Angeles,” said Regent Monica Lozano.

UC President Mark Yudof called it “a proud day for the University of California….This is what we do—public service.” He pledged that the new facility would deliver “not just adequate care” but “the best medical care.”

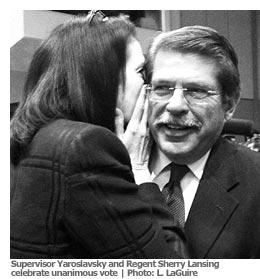

Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky first advanced the idea of a County-UC partnership in a Los Angeles Times Op-Ed piece last year. “What a difference 18 months makes,” the supervisor said. “This is going to be a great partnership.”

Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky first advanced the idea of a County-UC partnership in a Los Angeles Times Op-Ed piece last year. “What a difference 18 months makes,” the supervisor said. “This is going to be a great partnership.”

Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, whose district includes the hospital, summed up the feelings of many when he stated simply that the union between L.A. County and the University of California “will have a lasting effect on the quality of health care in Los Angeles.”

After years of mismanagement and patient care lapses, the hospital was dropped from the Medicare program in 2006 and was closed to in-patient services the following year.

Under the new agreement, which now goes to the Board of Supervisors for approval, the county would create a $50 million start-up fund for the hospital and pay $50 million a year to run it, with an additional $13.3 million in county funds going to support indigent care services at the facility each year. It also would provide a $20 million revolving line of credit.

In addition, the county is spending $208.5 million to rebuild the hospital facility and bring it up to seismic safety standards, and $145.3 million to build a new multi-service ambulatory care center (MACC) nearby.

For its part, the UC would provide the “broad spectrum of physician services necessary to operate the hospital” and would direct any teaching activities at the site.

A nonprofit corporation would oversee the new 120-bed hospital, with a seven-member board of directors appointed by the UC President and Los Angeles County.

The relatively small crowd inside the regent’s meeting room in Covel Commons on the UCLA campus on Thursday was sedate compared to the loud crowd of students outside protesting fee hikes. But they erupted into vigorous applause after the vote, and county officials in attendance embraced their UC counterparts.

“Now the real work begins,” L.A. County Chief Executive Officer William Fujioka said, noting that changes to the building schedule should allow completion of the capital project by the end of 2012. “The hope is to get this done in a three-year period.”

For many in the community who’ve followed the MLK hospital saga over the years, the UC’s involvement was critical—a “brilliant stroke,” in the words of Barbara Siegel of Neighborhood Legal Services. “It instills the confidence back into the hospital.”

“It will carry the imprimatur of quality that the UC is known for,” added Dr. Hector Flores, chair of family medicine at White Memorial Medical Center, who has been a close observer of MLK since he was appointed chair of the county’s Hospital Advisory Board in 2004.

Flores also noted that the county’s commitment to funding the new hospital is just as important—symbolically and practically—as the UC’s commitment to providing medical expertise.

“Knowing that there’s going to be a facility with safety net support from the county is important,” Flores said. “When you have a new facility in an underserved community, you worry that it’s going to end up closing.”

*Updated (12/1):

The Board of Supervisors today directed the county’s chief executive officer to hammer out specifics of a coordination agreement with the University of California for the new MLK hospital.

The supervisors also authorized CEO William Fujioka to create a project management team to oversee key next steps, including forming the non-profit and helping with its start-up; overseeing and coordinating the building process; and working out agreements on matters including indigent care.

“This is the beginning of a substantial effort,” Fujioka told the board.

The motion, by Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, requires the CEO to provide progress reports to the board at least every three months on project milestones and anticipated costs. An amendment by Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich directed Fujioka to provide “actual expenditures, both anticipated and unanticipated” on the project, as well as projected budgets for construction and for the cost of putting into place the organization that will run the new hospital.

At the meeting, Fujioka introduced members of the “King Team”—a cross-departmental group of 14 that has helped push the project to this point. Among those saluting their work was Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, who hailed the recent regents’ vote as an “important milestone” and said, “I just want to congratulate everyone who’s been a part of this.”

Regents’ landmark MLK hospital vote expected Thursday

November 18, 2009

After months of negotiations, the plan to create a thoroughly transformed hospital on the site of the former Martin Luther King Jr./Drew Medical Center comes down to nine people: the members of the University of California Board of Regents’ committee on health services.

After months of negotiations, the plan to create a thoroughly transformed hospital on the site of the former Martin Luther King Jr./Drew Medical Center comes down to nine people: the members of the University of California Board of Regents’ committee on health services.

The deal that UC Senior Vice President John Stobo will present to the committee Thursday morning at UCLA’s Covel Commons calls for the creation of a new community hospital—staffed by UC doctors, funded by L.A. County and governed by a newly-formed private nonprofit corporation.

Hundreds are expected to attend the meeting, a milestone in the difficult journey to chart a new course for MLK, which closed as an inpatient facility in 2007, following years of mismanagement, neglect and poor patient care.

The UC partnership idea was first put forward by Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky last year in an L.A. Times Op-Ed piece and has gathered momentum ever since. The regents’ vote would be the first to formally link the county and the UC on this project.

UC President Mark G. Yudof supports the proposed deal and is urging the health services committee to recommend its passage to the full board. If approved by the committee—which is headed by Sherry Lansing, the Regents’ vice-chair—the proposed agreement would move quickly to the full Board of Regents, which could take action immediately. The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors also would need to approve it.

“For myself, I can say that I am very, very supportive of it,” Lansing said Wednesday. She said that she had not discussed it with other regents but she believes that they, too, are committed, in general, to a mission of providing healthcare in under-served communities.

“I myself feel it’s a moral imperative,” Lansing said. “The holdback is that we’ve had these enormous cuts in the legislature…We needed to be assured from a financial standpoint.” She applauded the work of the county and of Stobo and said that she believes those assurances are now in place.

Under the agreement, the county would create a $50 million start-up fund for the hospital and pay $50 million a year to run it, with an additional $13.3 million in county funds going to support indigent care services at the facility each year. It also would provide a $20 million revolving line of credit. In addition, the county is spending $208.5 million to rebuild the hospital facility and bring it up to seismic safety standards, and $145.3 million to build a new multi-service ambulatory care center (MACC) nearby.

For its part, the UC would provide the “broad spectrum of physician services necessary to operate the hospital” and would direct any teaching activities at the site.

The nonprofit corporation in charge of the new 120-bed hospital—which could open as early as late 2012—would be overseen by a seven-member board of directors appointed by the UC President and Los Angeles County.

Although the UC’s analysis shows the new hospital would be expected to have a positive cash flow, the university system asked for and received a commitment from L.A. County to secure a $100 million letter of credit to “backstop” its commitment to funding the new institution over the first six years.

Olive View/UCLA Medical Center

May 13, 2009

Northeast Valley residents can look forward to greatly expanded emergency room services at Olive View/UCLA Medical Center under the hospital’s new ER project. On April 16, Yaroslavsky and other officials broke ground for new facility, which will offer 51 treatment areas in 32,000 sq. ft of space, virtually doubling the size of the existing ER, which currently handles 42,000 emergency and 19,000 urgent care visits annually. Among the numerous state of the art amenities will be 16 adult critical care rooms, six pediatric treatment rooms, five OB/GYN exam rooms, and a new 11,000 sq. ft. acute care/isolation unit with 15 two-person inpatient isolation rooms for patients with infectious diseases.

Northeast Valley residents can look forward to greatly expanded emergency room services at Olive View/UCLA Medical Center under the hospital’s new ER project. On April 16, Yaroslavsky and other officials broke ground for new facility, which will offer 51 treatment areas in 32,000 sq. ft of space, virtually doubling the size of the existing ER, which currently handles 42,000 emergency and 19,000 urgent care visits annually. Among the numerous state of the art amenities will be 16 adult critical care rooms, six pediatric treatment rooms, five OB/GYN exam rooms, and a new 11,000 sq. ft. acute care/isolation unit with 15 two-person inpatient isolation rooms for patients with infectious diseases.

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink