Children and Families

A slam dunk for mental health

December 21, 2010

No doubt, millions of viewers nationwide thought Ron Artest was simply having another Ron Artest moment.

The NBA veteran had long been known for his slightly—or largely—off-kilter comments and behavior on and off the court, including a violent charge into the stands in Detroit and an appearance on Jimmy Kimmel Live! in just his boxers.

So when an ABC reporter asked the first-year Los Angeles Laker for a comment just minutes after he’d sparked his team to a Game 7 triumph over the Boston Celtics, he let loose with a winner. He thanked his psychiatrist.

Yes, it was indeed a Ron Artest moment—but one that he says was premeditated and timed for maximum impact to let people know—especially the young people out there—that therapy had helped him work through many difficult chapters in his life. “I was doing it for a good reason,” he says of his expression of gratitude. “I didn’t know what was going to happen but I wanted it to take off.”

And take off it did.

Artest’s remark quickly set in motion an unusual collaboration that led on Tuesday to the debut of a public service announcement from Los Angeles County’s Department of Mental Health. (See video below.) Called “You Can Do It,” the spot features Artest on the court and was produced by the Hollywood executive behind the movie “The Soloist,” the story of L.A. Times columnist Steve Lopez’s relationship with homeless musician Nathaniel Ayres.

Artest openly credits an array of therapists and counselors with helping him relax and mature during a career that, for a time, brought him more notoriety than respect. He’s seen marriage counselors and parenting experts and therapists who specialize in the pressure-packed world of professional sports.

Artest says he also knows from growing up in the rougher neighborhoods of Queens how easy it is to be swept up in the criminal life or to simply lose your way in a family that is broken or abusive. “Some kids,” Artest says, “aren’t as mentally tough.”

This is the audience that the player and the mental health department hope to reach in the public service announcement, filmed last month at the Lakers’ practice facility in El Segundo. (See photo gallery and extended video interview with Artest below.)

Orchestrating the effort for the county has been clinical psychologist Dr. Alysa Solomon. She says that the minute she heard Artest give a shout-out to his “psychiatrist” (actually a psychologist), she dove for her Blackberry to e-mail her boss, mental health director Dr. Marvin J. Southard. “I was overexcited,” she says. “It was a universal jaw dropping moment.”

For nearly two years, Solomon had been leading the mental health agency’s “social inclusion” campaign, underwritten by California’s so-called Millionaires’ Tax and aimed at ending the stigma that too often stops people from seeking the psychological help they need. One way to do that, she thought, was to recruit celebrities who’d be willing to be interviewed by her about their own mental health issues—new territory for a department steeped in a culture of confidentiality.

First up was actor Tom Arnold, who has spoken widely of his battle with drug addiction and his life in recovery. The interview was filmed but lawyers for the actor blocked it from being seen, Solomon says, because the legal paperwork didn’t make clear that the county could not profit from the effort. “Our county counsel is not an entertainment law firm,” she says. “But we learned the process.”

In the meantime, Solomon had begun developing a friendship with violinist Ayres, who by then was receiving services from the mental health department. Solomon thought Ayres and Lopez would be perfect for the anti-stigma campaign. So she reached out to “The Soloist’s” producer. In him, she found a kindred spirit and a savvy ally.

From the earliest days of “The Soloist’s” journey from a book by Lopez to the big screen, producer Gary Foster was committed to infusing it with a sense of authenticity by shooting scenes in the heart of Los Angeles’ Skid Row. Although Robert Downey Jr. and Jamie Foxx would be the marquee names, the supporting cast would be the people of the streets.

“We thought it would be wrong to just be the circus that came to town and exploit what was going on down there,” explains Foster, who says the movie’s real-life characters were paid for their performances.

Throughout the filming, Foster and others involved with the project spent days in the teeming courtyard of a Skid Row housing and mental health agency called Lamp Community. There, he got to know the human beings behind Los Angeles’ homeless statistics and their daunting challenges with mental health. After his movie disappeared from theaters, Foster remained passionate about ways to communicate the need for psychological care to sufferers in all strata of society. He took a seat on Lamp’s board.

When Solomon pitched her idea for public service announcements, Foster says, it was a natural—“a great way for me to use my skills to further the mission.” Among other things, he’d know who to tap for help, such as Mob Scene Creative + Productions, an award winning entertainment marketing company that would take the lead in making the PSA.

But the anticipated starting lineup would need to be changed, with Ayres and Lopez taking a seat on the bench, thanks to Artest’s out-of-the-blue post-game comment and a highly publicized appearance at an East L.A. school, where he encouraged the kids to seek counseling if they were having troubles in their lives.

“Ron fell into our lap,” says Solomon, who was thrilled because of the athlete’s natural appeal to a demographic the mental health department had targeted—young teenage boys who might be too embarrassed or afraid to reveal their psychological struggles.

By mid-September, a short script had been jointly created by officials in the mental health department and advocates in the community. They dreamed of hearing Artest say: “I got help and got better, you can get better too. Take that first step and be a champion!”

Foster and Solomon then sent an e-mail to Artest’s publicist and friend, Heidi Buech, saying they’d “be honored to have Ron participate in our PSA program.” Within 24 hours, he was on board.

“Here’s one of the most unique celebrities in Los Angeles sports and he’s brave enough to talk about his personal life,” Foster says. “I think it’s going to have great therapeutic effect.”

Artest, for his part, says the decision was easy.

“People need to be educated,” he says of those who denigrate the value of talking to professionals. “People think you’re crazy or weak but that’s not true.” More specifically, he says, “I’m trying to help build confidence and a support system for kids that don’t have one.”

Although he wanted to create a bit of a stir by thanking his Houston-based sports therapist after the NBA finals, he says he never intended to be “one of the faces of the movement.” He says he “inherited” it.

“Once I said what I said, it was like, wow!”

And there’s more to come.

On Christmas night, Artest will announce the winner of a raffle for his first and only championship ring. The proceeds from “Win My Bling,” which amount so far to almost $600,000, will go to a number of mental health charities and to Artest’s Xcel University, a foundation he established to help at-risk kids build self respect and overcome their difficult environments.

Then in February, he’ll be headed to Washington D.C. to testify on behalf of HR 2531, a bill sponsored by Rep. Grace F. Napolitano (D-Ca.) that is aimed at boosting mental health services in schools.

“It’s like going into the NBA,” he says. “I never dreamed I’d be in the NBA. And I never dreamed I’d be going to The Hill. Ever.”

And that’s something to talk about.

The Ron Artest/ Los Angeles County public service announcement.

http://zevyaroslavsky.org/videos/RAP_BeAChampion30_TEXTED_FINAL_HD-Fixed.f4v

An extended interview of Artest by Dr. Alysa Solomon of the mental health department.

A photo gallery from the PSA filming in El Segundo.

Posted 12/12/10

Beating the holiday blues

December 16, 2010

It’s the most wonderful time of the year – or so the song goes. But stress, loneliness and other unwelcome feelings can also be as ubiquitous as red-nosed reindeer during the holidays. So what can you do if “merry and bright” isn’t exactly summing up your December?

In preparation for the season, we checked in with the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health and its medical director, Dr. Roderick Shaner.

For most people, he says, the sources of holiday stress “seem to boil down to a couple of big things: One is concern about fellowship and being lonely. And the other is the set of expectations we have, both for the holidays and for ourselves.”

So what can you do to manage the blues and the expectations? Here’s Dr. Shaner’s advice:

1. Cut yourself some slack in the holiday spirit department.

“Unless you’re up at the North Pole making presents,” he says, “probably between 99.99% and 100% of the population experience stress around the holidays.” Feeling compelled to have the “right” frame of mind can be its own sort of holiday oppression. If your mood isn’t great, hey, you’re not alone — it’s an epidemic. Bad moods don’t get better by being taken too seriously.

2. Remember what people actually want for Christmas.

“We all remember those perfect holidays we had a long time ago, that weren’t so perfect in retrospect,” Dr. Shaner says with a laugh. “And we see in the media all these idealized versions of what we’re supposed to be in the holidays — happy, calm, making everyone feel special. Well, there are no perfect holidays. Our idealized versions are just that.” Buying into all those “shoulds”, he says, just puts you at risk of overextending yourself financially, socially, physically and emotionally — and unnecessarily. “What the people in our lives want most from us is just to see us, and know we love them, and that we have ties to them.”

3. Get real.

“Think realistically about what you’re going to be doing around the holidays, and about what you can and can’t do in terms of scheduling,” Dr. Shaner says. “Make a budget. Make some pre-holiday resolutions about the degree to which you will watch what you eat and drink, how much sleep you’ll get, how much work you’ll do. Recognize that you’ll need good rest, a reasonable schedule of exercise. And then recognize that the holidays are a time when you’ll want to give yourself a little more leeway, and resolve not to beat yourself up.”

4. Look ahead.

“We’re not going to become someone different in the last two weeks of the holiday season, but one way of dealing with the pressure of expectations is to focus on the future,” says Dr. Shaner. So think about where you want to be in the coming year. There’s a reason New Year’s resolutions are a tradition. “It’s a way to recognize not only our limitations, but also our potential. We remember that we’re all works in progress, and that makes us more hopeful and probably happier as well.”

“This is the kind of season in which human ties are most important,” says Dr. Shaner. “When we lose those, it’s easy to drift into despair.” Connect with your family. So what if the folks back home will complain that you haven’t called in six months? Or that you must admit to them that your love life or resume or show business prospects aren’t what you’d hoped for? “Your family and friends can lift your spirits, just as you’ve lifted theirs with your call,” notes Dr. Shaner. If family isn’t an option, try connecting with friends, community groups or neighbors. If seeing someone in person isn’t feasible, send cards. Or texts. Or Facebook greetings. “Actually a lot of what therapy is is helping people reach out,” says the doctor. “People think that isn’t enough, but it often is.”

6. Do something nice for someone.

“Rates of suicide and depression are higher during the holidays, and this is especially true of the poor and the homeless,” he says. “This is the time when those people are most in need of outreach and social inclusion.” You don’t have to do a lot — sometimes even a smile or a season’s greeting is plenty. But, he adds, being nice also happens to be one of the nicest things you can do for your own emotional well being. “Reaching out to people who may be more lonely and isolated is also one of the best ways to combat our own loneliness and isolation.” Ask any volunteer — serving a meal at a soup kitchen, hanging out for an afternoon with someone who’s sick or shut-in, pitching in at your place of worship or local food bank, even donating blood or giving to a good cause can make you feel surprisingly fabulous.

7. Get help if you need it.

When flu season rolls around, you get a flu shot. You call a doctor when you can’t get rid of that cold. If you’re prone to asthma or diabetes, you get regular check-ups. Mental health is just as important. Plus, it’s one of the best forms of preventative medicine on the market. So see somebody. If your insurance doesn’t cover what you need, there are teaching clinics, nonprofits, therapists who work on a sliding scale and counselors who work with faith-based organizations. Don’t know where to start? Try the Department of Mental Health’s new resource page, or its access line at (800) 854-7771. Thinking about investing in yourself for Christmas? L.A. has some of the best therapists in the country. More serious concerns? L.A.’s Suicide Prevention Center Hotline — (877) 727-4747 — has been in business for more than a half-century. “Our community has many resources that can be helpful,” says Dr. Shaner, “but ironically, it’s the stress and worry itself that often keeps people from them.”

A CalFresh start

November 19, 2010

It was a long time ago, but when Bob McKinnon traces the successful trajectory of his life—his Madison Avenue advertising career, the creation of his own boutique firm—he thinks about food stamps.

He remembers how they helped him eat better so he could study harder. His mom, a single mother of three, had been diagnosed with cervical cancer and needed help from the government to steady her family during the rough patches.

But McKinnon also remembers the way some people denigrated that helping hand, calling it a handout “for people who are lazy or aren’t trying.” And, in that regard, not much has changed over the years. The stigma lingers. Only now, McKinnon, 41, is in the forefront of a movement in California to do something about it.

McKinnon, the founder of a public-spirited communications and advocacy firm in New York, was enlisted to help California rebrand its food stamp program in the hopes of undoing decades of negative stereotypes and encouraging eligible participants to step forward and sign up.

In October, California’s food stamp program officially became known as “CalFresh: Better Food for Better Living.” The name—and accompanying logo—followed months of consumer research, strategy sessions, stakeholder meetings and focus groups from Merced to San Bernardino, comprised of low-income Californians receiving assistance or eligible for it.

“Looking back, to think that at some point my mom had to feel badly for even a second to help us, bothers me to do this to this day,” says McKinnon, whose company, YellowBrickRoad, specializes in “advocacy communications” on issues ranging from childhood obesity to climate change. “Do critics of these programs really think people don’t want to feel pride?”

The rebranding process began two years ago, when the U.S. Department of Agriculture changed the name of the food stamp program to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP. The change was made to reflect the reality that food stamps and scrip were abandoned years ago in favor of electronic debit cards. The federal government told the states they could adopt the same name for their programs or come up with new ones.

California seized the challenge like no other—for good reason.

The state’s 3 million food assistance recipients represent just half of those eligible for the benefits. Only Wyoming has a worse record. As a result, California has been missing out on an estimated $4.9 billion in federal nutrition assistance that would flow through the state’s ailing economy. The program pays a monthly benefit of $200 for an individual and $526 for a household of three.

The California legislature, with a strong push from Oakland-based California Food Policy Advocates, passed a bill in 2008 by Assemblyman Jim Beall, Jr. that not only called for the creation of a new name but also lifted asset restrictions that effectively required some applicants to exhaust virtually their entire net worth to qualify.

“One of the things we wanted be clear about is that we didn’t want to put a new name on an old program,” says George Manalo-LeClair, senior director of legislation for CFPA, which assured lawmakers that no public money would be spent on the process. “We recognized that this was not the No. 1 priority for the state.”

To research and test potential names for the state’s Department of Social Services, The California Endowment stepped in with a grant of $150,000, enough to cover some of the costs of YellowBrickRoad and Lake Research Partners, which conducted the focus groups.

Manalo-LeClair says his group and others were determined to come up with a name that would resonate positively with potential participants, many of whom have been hit hard by the economy but could not see themselves applying for food stamps. The idea was to create branding that stressed the nutritional, rather than the welfare, aspects of the program.

California officials, Manalo-LeClair says, didn’t want to follow the path of the federal government, which “took words that the House liked and that the Senate liked and squished them together.” The result, he says, was a name that focus groups agreed conjured up images of a welfare program with “long lines and hassles.”

It was during these sessions, as interviewers asked participants to offer words that suggested healthy eating, that “fresh” first surfaced. Many involved in the process liked that it worked on two levels—fresh, as in fresh food, and fresh, as in “you’ve hit rock bottom and need a fresh start,” as McKinnon put it.

Some within the bureaucracy, however, weren’t nearly as thrilled when presented with the proposed CalFresh name. They thought it was vague and confusing. Without the tag line, it didn’t even allude to the program’s key aspirations—to provide food and help. How would people know even to apply?

“When you’re dealing with government stakeholders, they want to come up with a lot of acronyms,” McKinnon responds. “But you’ve got to ask: Who is our audience? We need to make sure that the name appeals to them first. To us, a little bit of abstraction was perfectly acceptable so people could see themselves in the program.”

But the criticisms from the insiders, who were concerned about the program’s success, were mild compared to those that came after California’s first lady Maria Shriver unveiled the rebranding during a media event in Long Beach. Conservative radio hosts and bloggers feasted on the change.

Typical among them was this from self-proclaimed “Advice Goddess” blogger Amy Alkon, the author of a recent book bemoaning the lack of civility in American life : “Sorry, but there should be a stigma against using food stamps…My parents raised us to think it was shameful not to support yourself.”

Food advocates in and out of government seethe when they hear intentionally provocative off-the-cuff takes like these, which misrepresent the demographics of those receiving help and the impact of the nation’s economic meltdown on working families. The fact is that children represent roughly half of the recipients.

“Someone with an opinion like that might lose their job tomorrow and then need food assistance themselves,” says Judith Lilliard, who oversees the food stamp program for Los Angeles County’s Department of Public Social Services. “We’re trying to build a healthy society here. We don’t want people starving in the streets because they’re embarrassed to apply for food stamps.”

To that end, Lilliard’s department has been a leader in streamlining the application process, allowing people to sign-up by mail, phone and, soon, through the Internet. The county also recently began a mobile service, dispatching a computer-outfitted truck into neighborhoods with high numbers of eligible participants.

Underlying all these efforts, Lilliard says, is recognition by the county that many of the working poor will not enter a government building to apply for food assistance because they feel it’s humiliating.

Lilliard, like McKinnon, knows something about that feeling.

In the mid-1960s, she grew up in housing projects in East L.A. and low-rent apartments in South-Central. She remembers tagging along with her mom to pick up the family’s food stamps, which back then were distributed by banks. The recipients were told to line up outside at a walk-up teller.

“I remember thinking, “This is not right. Why are we out here when they have a perfectly good building,’ ” Lilliard says. “The bank felt that people getting food stamps weren’t good enough to go inside the building.”

Lilliard says that, over the years, she’s held a variety of positions within her department’s general relief and food stamp division. (“We’ll be renaming that soon, by the way.”) But it was her pre-teen years that Lilliard says have given her a special qualification for her job as division chief—empathy.

“I’m good at being able to put myself in someone else’s shoes,” she says, “because I’ve been there myself.”

DCFS data collection called “colossal mess”

November 3, 2010

Two weeks ago, in an effort to find possible trends in the tragic deaths of youngsters who’d come to the attention of Los Angeles County child welfare officials, the Board of Supervisors asked for data on fatalities dating back two decades.

.

On Wednesday, however, a clearly angry Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky said the board would be lucky to get useful information from just two years ago, calling the data collection efforts of the Department of Children and Family Services “a colossal mess.”

Yaroslavsky said the Chief Executive Office has expressed concerns that the historical information may not even be available. This, Yaroslavsky said, “begs the question: What is the Department of Children and Family Services basing any of its policies on when it comes to protecting children’s lives?”

The supervisor’s remarks came during yet another debate—and more motions—involving the performance of DCFS, which has come under withering criticism in the wake of numerous child deaths and the department’s failure to publicly disclose some of them.

One of the motions, approved by the board during its Wednesday meeting, called for a single county entity to track and compile information on child deaths related to abuse or neglect. Another motion called for the reversal of the board’s earlier request for 20 years of fatality data in the belief that it’s better to look forward than back.

But the board majority disagreed. Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, who had co-authored the motion for historical information with colleague Michael D. Antonovich, said that without such data, “the best you do is find yourself being driven by the anecdotal rather than analytical.”

Acting on a compromise suggested by Yaroslavsky, the board scaled back its request to10 years. Although the department may be unable to generate even that data, Yaroslavsky said, the effort should still be aggressively pursued in the spirit of transparency for a public that “is livid” with the county, from the top down.

If the information isn’t available, then “the public ought to know that the Department of Children and Family Services can’t respond to that kind of fundamental question,” he said. “But to just pull out and say, ‘Never mind. We don’t really want to do that,’ is not the way I want to do business.”

He added: “I think we should stop being defensive about this and just let the chips fall where they may.”

Posted 11/3/10

East Coast prof plays ball with L.A.

October 7, 2010

Among social services experts in Los Angeles, Dennis Culhane is considered top drawer. During the past few years, he’s won many fans for his cutting edge collaboration with county officials in determining how government services are used by the region’s disadvantaged populations.

Among social services experts in Los Angeles, Dennis Culhane is considered top drawer. During the past few years, he’s won many fans for his cutting edge collaboration with county officials in determining how government services are used by the region’s disadvantaged populations.

Culhane also likes a good baseball game, which makes it a good thing he lives 2,500 miles away. On Wednesday, he was in the stands in Philadelphia as the home-team pitcher threw a no-hitter against the Cincinnati Reds in their first playoff game.

“I love Philly,” said Culhane, a professor of social policy at the University of Pennsylvania.

Talk about your telecommute.

Culhane is now embarked on another study with L.A. County. This one will track the kinds and costs of government services used by about 30,000 former foster children and probation youths who left the county’s care—or “aged-out”—between 2002 and 2004. The hope is that the analysis will lead to improving and streamlining programs.

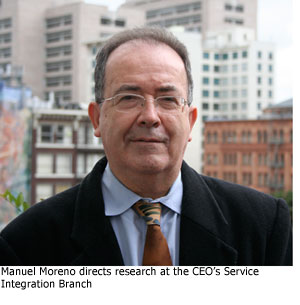

The innovative research relationship began in 2007, when Culhane met Manuel Moreno of the Chief Executive Office at a gathering on homeless policy at UCLA. Moreno was well regarded in his own right; Computerworld Magazine named him one of this year’s top 100 information technology innovators for his work in consolidating data across the county’s social service agencies.

The two researchers hit it off.

“They were really far ahead of the curve,” Culhane said of the work being performed by the research arm of the CEO’s Service Integration Branch, which Moreno heads.

“He’s an academic who really knows how to address policymakers in ways they understand,” Moreno said of his East Coast collaborator, who coauthors an annual report to Congress on homelessness.

Within a year of their meeting, Moreno and Culhane had tackled a joint project detailing the costs and types of county services being used by the county’s General Relief recipients. Joining the two back then was Culhane’s frequent research partner, University of Pennsylvania assistant professor Stephen Metraux, who also is involved in the current study of foster care and Probation youth.

Within a year of their meeting, Moreno and Culhane had tackled a joint project detailing the costs and types of county services being used by the county’s General Relief recipients. Joining the two back then was Culhane’s frequent research partner, University of Pennsylvania assistant professor Stephen Metraux, who also is involved in the current study of foster care and Probation youth.

That effort, funded by a $275,000 grant from the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, will reach beyond data collected by county departments and include state educational and employment records.

The researchers hope to be able to determine which transitional programs work best by seeing how the youth fared in staying in school, obtaining jobs and avoiding legal trouble. They’ll also explore issues of substance abuse and other health and mental health issues.

Data for the study should start flowing to Culhane at the University of Pennsylvania within a month or so, after information-sharing agreements are signed with state and county agencies. The report is scheduled for completion next spring.

“Working with Dennis,” Moreno said, “we are going to be able to tell how the youth have fared either in becoming self-sufficient or in becoming dependent on government services.”

The Department of Children and Family Services is eager for the results.

“Studies like this one help us identify how resources can be used more effectively to help children during a very challenging time—the transition to adulthood,” said DCFS director Trish Ploehn.

The researchers have more projects planned down the road.

Culhane is currently consulting with Moreno on a cost-benefit analysis of Project 50, the innovative program that provides housing and other services to Skid Row’s most chronically vulnerable homeless men and women.

The two men also plan to explore how veterans in Los Angeles use local services as part of a MacArthur Foundation grant Culhane is overseeing.

Posted 10-6-10

Secret child-death records to be revealed

August 31, 2010

Los Angeles County’s top child welfare official—confronted with contradictions in her agency’s own records—vowed Tuesday to make public the deaths of dozens of children who’d been abused or neglected but whose cases had been questionably kept secret.

That pledge from Trish Ploehn, director of the Department of Children and Family Services, came on the heels of an independent study that raised new concerns about the agency’s compliance with a 2008 state law requiring the disclosure of child deaths that result from abuse or neglect.

The report, written by the county’s Office of Independent Review, said DCFS’ actions had effectively “frustrated” the law’s goal of preventing future tragedies by enhancing public scrutiny and promoting a more informed debate from which sound policy can flow.

For a third straight week, the issue of public access to child-death documents dominated the Board of Supervisors meeting—this time with less rancor but with a slew of new questions that have turned up the heat on Ploehn, who has spent the better part of a year defending her department and its stewardship.

On Tuesday, during her testimony before the board, Ploehn managed to diffuse some of the latest criticism by quickly making it clear that she agreed “100 percent” with at least one of the more troubling findings in the Office of Independent Review report.

The report disclosed that DCFS, in confidential dependency court documents, had classified upwards of 60 child deaths as resulting directly from neglect and abuse. But when it came to complying with a state law known as SB 39, DCFS exempted many, if not all, of those cases from public disclosure by concluding that they were not directly caused by abuse or neglect.

Ploehn blamed a lack of communication—and a difference in missions—between the two branches of her office responsible for the conflicting findings.

The dependency court filings, she said, relied on a broadly worded statute used to immediately remove at-risk siblings from homes where children had died and where there’d been evidence of abuse or neglect. The SB 39 cases, she said, required a much narrower finding that the death of a child was caused specifically by abuse or neglect.

“There was no communication or consultation going on between these two entities,” Ploehn told the board. “Therefore, we were in parallel universes.” She said every case in which DCFS had invoked the most serious claims of abuse or neglect in court filings would now be reclassified as a public document under SB 39 “and we will release those records.”

Michael Gennaco, who heads the Office of Independent Review, said he found no evidence of a concerted effort by DCFS to conceal child death cases. During the review, the OIR “received no information to believe that this alleged inconsistent approach in assessing child fatalities between different components of DCFS was either intentional or designed,” Gennaco wrote in his report and repeated during his Tuesday testimony before the board.

That statement, however, brought a quick word of caution from Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky.

“I don’t think you have all the information that you’re going to have going forward,” Yaroslavsky warned Gennaco, adding: “There are reasons to believe this is not just an accidental disconnect, [that] the left hand didn’t know what the right hand was doing.”

Last week, Yaroslavsky raised the possibility that DCFS may be failing to comply with the public disclosure requirements of SB 39 to shield itself from criticism. Specifically, he pointed to the case of an 11-year-old boy who had hung himself in June after years of physical abuse. That case, Yaroslavsky said, had not been publicly disclosed, even though the boy’s suicide seemed to be the direct result of the abuse he suffered.

On Tuesday, under questioning from Yaroslavsky, Gennaco acknowledged that the boy’s death was one of the anonymous examples in his report, one in which DCFS had cited abuse as the cause of death in court documents but made no similar finding under SB 39.

“The issue for me is whether…the public is getting complete and accurate information about child deaths, which was the purpose behind SB 39 in the first place in 2008,” said Yaroslavsky, who praised a series of recommendations Gennaco offered to bring more clarity and continuity to DCFS’ procedures. “I raised it last week and I was right.”

In his report, Gennaco said that DCFS’ public disclosure of child-death cases also had dropped dramatically in the past two years because of “blanket law enforcement objections to the release of information.” He blamed this on DCFS’ failure to give law enforcement officials copies of the files to determine what information might—or might not—jeopardize an ongoing criminal case. In the absence of such details, Gennaco said, it’s understandable that law enforcement agencies would opt to keep the entire case confidential.

“It is apparent that that the stream of information about SB 39 child deaths that was flowing in 2008, has been largely shut down two years later as a result of law enforcement’s blanket holds,” Gennaco wrote.

So many Los Angeles County cases are being excluded from public disclosure in this way under SB 39, Gennaco said, that there’s “a virtual paralysis of the statute’s intent.”

He suggested that DCFS immediately begin providing more information to law enforcement agencies before decisions are made about public disclosure and that continuous reviews are made of case files to determine when additional information can be released.

Overall, Gennaco concluded, DCFS must develop a mindset and procedures that recognize the intent of the state law is to provide more, rather than less, information to the public and thus “ensure that there is a consistent and principled determination of what constitutes SB 39 cases subject to disclosure.”

Posted 8/31/10

New bill would broaden child welfare database

August 26, 2010

Los Angeles County child-welfare officials won an important victory in Sacramento this week in the quest to help social workers better investigate allegations of child abuse.

Los Angeles County child-welfare officials won an important victory in Sacramento this week in the quest to help social workers better investigate allegations of child abuse.

Passed unanimously in the Assembly and Senate, Assembly Bill 2322 expands information available to county social workers in a computer database called the Family and Children’s Index (FCI), which provides child welfare workers with key medical, law enforcement and social services data as they launch child welfare investigations.

The new legislation would allow Los Angeles County to include in FCI convictions for crimes against children by family members and others living with a child who has come to the attention of child welfare authorities.

“This will provide key information for social workers who often have to make split second decisions about how best to protect a child,” said Dawyn Harrison, a principal deputy county counsel working on FCI issues.

Under the old system, social workers had to wait days or weeks to obtain information about convictions of family members and could learn nothing about convictions of non-family members. Speed is crucial when Department of Children and Family Services emergency workers use FCI as they launch investigations into reports of alleged abuse or neglect.

The bill, sponsored by Assemblyman Mike Feuer and former speaker Karen Bass, is awaiting the signature of Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger.

“We have indications that he is going to sign it,” said Ryan Alsop, the county’s assistant Chief Executive Officer for intergovernmental and external affairs.

The new law would take effect immediately.

Posted 8/26/10

New conflict over child death records

August 24, 2010

For a second consecutive week, the Board of Supervisors tangled over the release of information on the deaths of children who’ve had a history of contact with Los Angeles county child welfare authorities.

For a second consecutive week, the Board of Supervisors tangled over the release of information on the deaths of children who’ve had a history of contact with Los Angeles county child welfare authorities.

The board unanimously approved a motion by Supervisor Gloria Molina asking for an independent analysis of what information the supervisors can—and cannot—make public about child deaths allegedly caused by abuse or neglect. That study will be undertaken by the county’s Office of Independent Review.

Molina’s motion comes one week after Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky said during a board session that county officials seemed more concerned with plugging leaks than with fixing problems in the Department of Children and Family Services. His comments prompted strong reaction from some of his colleagues and seemed to be a subtext of Molina’s motion on Tuesday.

“All members of this Board support transparency and the County’s duty to disclose information in the public interest—particularly when such information involves the death of vulnerable children,” Molina said in the motion. But she said the board also has a legal duty to protect confidential child information and that the law provides “a clear path” for the disclosure of such data.

“The failure to support ‘leaks’ of sensitive personal and case information outside these legal processes should not be construed as a rejection of transparency,” Molina said in a veiled rebuke to her board colleague, Yaroslavsky.

Yaroslavsky, for his part, pursued a provocative new tack in questioning DCFS’ commitment to transparency. He suggested that the embattled department may intentionally be classifying some child deaths in ways that keep them secret.

Under a California law called SB 39, certain information is made public about a child’s death when it is determined to have resulted from abuse or neglect. Once that determination is made, the public can then seek more detailed information. Without a finding of abuse or neglect, the case remains untraceable.

Yaroslavsky was skeptical of the large number of deaths that DCFS determined were not caused by abuse or neglect in recent years, including the shocking suicide in June of an 11-year-old boy named Jorge T., who’d endured a history of documented physical abuse. Yaroslavsky said DCFS concluded that that death was not the result of abuse or neglect and was not subject to disclosure under SB 39.

“What I’m interested in knowing,” the supervisor said, “is how many other Jorge T.-type cases are there where arguably the death may not have come at the hands of another, but the death was clearly caused by the cumulative abuse and neglect over a period of time. And I think the department has an interest in minimizing the number of cases that they put on the SB 39 list because, frankly, it makes them look better.”

“I think somebody’s making a call on some of these cases that just doesn’t meet the smell test for me,” Yaroslavsky added.

At one point in the discussion, County Counsel Andrea Sheridan Ordin told Yaroslavsky that she believed Jorge’s case was still being investigated and that no determination had been made about whether his suicide was the result of abuse or neglect.

“You believe or you know?” Yaroslavsky asked her.

“I believe,” she responded.

Yaroslavsky’s continued line of questioning prompted this personal barb from Molina: “I know you’re interested in misinforming everyone about what the department [DCFS] is doing or not doing.”

Following the meeting, Yaroslavsky said that “a decision was made many weeks ago not to classify Jorge’s death as an SB 39 case—a determination that has not been changed as of today, more than two months after the youngster’s suicide.”

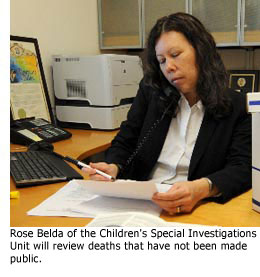

Prior to Tuesday’s session, Yaroslavsky had hoped to gain support for a motion directing the Children’s Special Investigation Unit (CSIU) to examine whether cases were wrongly excluded from SB 39 disclosure, “thereby preventing a public discussion and the development of policies that could help avert such deaths in the future.” But when it became clear that his colleagues were unwilling to pass the measure, Yaroslavsky said he used his authority to individually ask CSIU to undertake the review.

Rose Belda, who heads the unit, testified Tuesday that based on her experience, the list of SB 39 cases could be “construed in a more expansive way, if that was the desire.”

Posted 8/24/10

Leak probe goes public, finally

August 17, 2010

An investigation of leaks involving the county’s Department of Children and Family Services is diverting attention from the more pressing work of protecting children from the kind of harm that has drawn so much media interest, Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky said Tuesday.

An investigation of leaks involving the county’s Department of Children and Family Services is diverting attention from the more pressing work of protecting children from the kind of harm that has drawn so much media interest, Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky said Tuesday.

“The obsession with leaks seems to me to exceed the obsession with the child deaths,” Yaroslavsky said. “This seems to be No. 1 on the list—how to plug these leaks.”

Yaroslavsky’s remarks came during a public session in which the supervisors spent more than an hour discussing a motion that, on the surface, seemed fairly straightforward. The motion, which passed 4-1, called on all county departments to assist the Chief Executive Officer’s inquiry into the disclosure of “confidential child welfare information,” an inquiry that CEO William T Fujioka said should be completed by week’s end.

But behind the motion—opposed by Yaroslavsky as a distraction from the real work at hand—were a series of events that raised questions about why the inquiry was launched and whether it was done in compliance with the Brown Act, a state law requiring that official actions be taken in public except in limited circumstances.

The issue of leaks about DCFS cases was raised in a closed session last week in which no explicit mention of the matter had been listed on the meeting’s agenda.

The only reason the issue was placed on this week’s agenda was to “cure” what may have been violations of the Brown Act, County Counsel Andrea Sheridan Ordin acknowledged.

During Tuesday’s lengthy discussion, it was disclosed that CEO Fujioka initiated the investigation last month after embattled DCFS Director Trish Ploehn complained that her staff was being undermined and demoralized by leaks of confidential information that suggested they’ve acted negligently in protecting abused children.

In the closed-door session last week, Fujioka asked the board for authority to examine e-mails of a supervisor staffer suspected of possibly leaking confidential information to the media, Yaroslavsky said. Fujioka, he said, did not have access to a separate e-mail system for board members and their staffs.

In their closed-door session, the supervisors decided that requests for their e-mails—as well as those of their staffs—should be made available to the CEO through the board’s Executive Office to restrict any “rummaging through” Board of Supervisors e-mails. Several times during Tuesday’s public meeting, Yaroslavsky stressed his belief that this same process should be used for future requests for e-mails by the CEO’s office.

In their closed-door session, the supervisors decided that requests for their e-mails—as well as those of their staffs—should be made available to the CEO through the board’s Executive Office to restrict any “rummaging through” Board of Supervisors e-mails. Several times during Tuesday’s public meeting, Yaroslavsky stressed his belief that this same process should be used for future requests for e-mails by the CEO’s office.

Supervisors Gloria Molina and Mark Ridley-Thomas were most vocal in their arguments in favor of the motion requiring all departments to cooperate in the DCFS leak probe. They said it was simply a reflection of the legal realities and their board responsibilities. “We have a duty to ensure that these [confidential] documents are preserved and protected,” Molina said.

Yaroslavsky agreed that confidentiality should be respected but questioned the amount of time being consumed on the issue at a time of crisis for DCFS.

“If you have a good lead, by all means pursue it,” Yaroslavsky said. “But you can spend all of your waking hours trying to plug a leak and not addressing the root cause of what the leaks are all about, which is a frustration with the number of children who are dying under our care.

“That’s why I’m not voting for this,” he said of the motion. “I think symbolically, among other things, it sends the wrong message to the public, not to mention to our own organization.”

Fujioka, for his part, took strong exception to the supervisor’s suggestion that the department is not singularly focused on child protection.

“I need to state that is an absolutely incorrect statement,” Fujioka said, noting the “ton of time, effort, commitment and passion” that has gone into trying to stem the tide of child deaths. He defended his investigation, saying the disclosure of confidential information could compromise the department and its work on behalf of troubled families.

Posted 8/17/10

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink