Children and Families

A better place for kids to wait

August 22, 2012

A toddler gets a lullaby from a certified nurse assistant at the county's new Child Awaiting Placement Center.

The toddler in the pink shoes had arrived early Sunday, after her single father was taken into custody on a DUI. Social workers called foster home after foster home, but none would take her. One woman agreed, then reneged, saying she couldn’t handle a 21-month-old baby. A grandmother was willing, but her home wasn’t safe.

As precious hours passed, the frustration continued. But there was at least one consolation for the displaced child: For the first time in nearly a decade, tots in her situation had somewhere to wait besides the Department of Children and Family Services command post. When bedtime came, the toddler got a warm bath, a hot meal, a clean crib and a loving shelter in a brand new county center for children awaiting foster care.

Tucked into a corner of the Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center campus, the county’s new Child Awaiting Placement Center has been operating to rave reviews since July 16. The CAP Center can feed, house and care for as many as 15 children up to the age of 10 while DCFS workers canvass for foster homes.

The center opened after reports last year that DCFS was housing children in the department’s Emergency Response Command Post when social workers couldn’t find placements, and downplaying the situation because they feared repercussions from their managers.

Though the command post was created to investigate child abuse allegations on nights and weekends, it has morphed in recent years into a de facto children’s shelter; since the 2003 demise of the troubled MacLaren Children’s Center, the command post is the only DCFS office that never closes.

But the command post—a suite of offices that moved last year from a Wilshire Boulevard high-rise to the downtown L.A. Mart, which houses high-end furniture showrooms—does not have a state license to house children, and by law cannot provide shelter for more than 24 hours.

Earlier this year, county auditors reported that they had seen as many as 10 infants, children and teenagers at a time sleeping at the command post last year. Some older children had histories of violence and severe mental illness, and some babies were sleeping in car seats.

Meanwhile, auditors found, social workers were struggling to find emergency placements; on one night, 11 of 14 foster care facilities called by command post staffers simply let the phone ring; the other three were either filled, closed or had changed their phone numbers.

“We had all these kids coming in,” says DCFS Regional Administrator Frank Ramos. “And we were trying to make sure they were safe in this business office. But at the same time we also had to respond to, say, officers who just did a drug bust and had called to say, ‘We’re at the home, and we need you to come now.’ ”

Enter the CAP Center, which was conceived two years ago by Dr. Astrid Heger, who directs the county’s 24-hour hub for treating victims of child abuse. Housed in a bright, loft-like space that spans a sleeping area, a big playroom, a child-scaled bathroom, a playground and an eat-in kitchen, the center is adjacent to Heger’s clinic.

“It used to be a child care center for employees and patients at the [County-USC] Medical Center before they moved to their new hospital building,” says Heger, adding that after the move, the area reverted to storage space.

Because children who come to the command post are brought to Heger for medical examinations, she says, she saw the need coming. “All the emergency response workers who were coming in here kept saying, ‘Can’t we just leave these kids here? Because the command post isn’t a very good space for them to be in,’ ” she recalls.

Heger’s operation, a multi-disciplinary project known as the Violence Intervention Program, is publicly funded, but also is subsidized by a foundation; deciding that “if we build it, they will come,” she asked one of her private donors, children’s author Cornelia Funke, to help renovate some of the county hub space.

When the Board of Supervisors inevitably demanded action, she says, the space was prepped, thanks to Funke’s $100,000 donation. DCFS kicked in $40,000 for touch-ups, and the founders of Guess? Inc. donated furniture, adds Heger.

The proximity to VIP ensured that medical care and mental health services would be available if needed; the hospital supplied hot meals for the children. Although DCFS officials estimate the center eventually will cost about $2 million to operate with its own staff, the Department of Health Services has for now sent certified nurse assistants to cover the first two months of childcare. DHS leases the space to DCFS at no cost.

Forty-six children arrived during the center’s first week. On the first Saturday night, 14 of its 15 beds were filled. “There were sisters asleep on the couch with their arms around each other, and a teenaged mom with her 2-year-old over there on a futon,” Heger recalls. “It was the way it should be—everybody was sleeping with real pillows and blankets on real furniture.”

As of last week, CAP had sheltered 194 children, and only one—the toddler in the pink shoes—had overstayed the 24-hour limit. Meanwhile at the command post, which for now remains the waiting area of last resort for adolescents, the headcount of waiting children is down by about 40%, to roughly 50 per week.

DCFS Assistant Regional Administrator Maricruz Trevino, who moved from the command post to run the CAP Center, says the new facility is a godsend, but the county’s work is far from finished. From the strained economy to an increased reluctance among foster parents to take babies, she says, a chronic shortage of willing foster homes continues to plague the county.

“This is wonderful,” she says, as she smiles down at the toddler in the pink shoes, who beams back, proffering a little toy bowl of pretend “soup.”

“But the resources in our community have to be gathered. We have to find a place for more of our kids.”

Like the three bears and their porridge, children awaiting foster care now have a setting that is "just right."

Posted 8/21/12

Browning tapped for DCFS turnaround

February 14, 2012

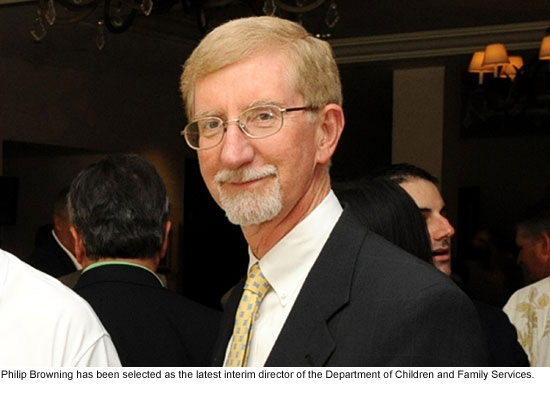

Philip Browning brings management turnaround expertise to his new Children and Family Services post.

When it comes to overhauling the county’s long-troubled Department of Children and Family Services, Philip Browning isn’t messing around with any halfway measures.

“What I’d like is within two years to be the national leader, for L.A. County to be the model for other jurisdictions in the child welfare area,” said Browning, shortly after being named to the agency’s top job Tuesday by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors. “That’s my goal.”

Browning has been at the helm of the agency for the past six months as interim director. He was originally recruited to come to Los Angeles County in 2001 from Washington, D.C., where he served as the district’s child support director. His first assignment here was to remake the District Attorney’s child support division, one of the most troubled in the nation. With Browning in charge, collections increased 36%, to more than $500 million, as customer service improved dramatically.

“We got more complaints about child support than any other agency in the county before he arrived,” said Board of Supervisors Chairman Zev Yaroslavsky. “He turned it around and now we get virtually no complaints.”

Next up for Browning in 2007 was running the county’s sprawling and complex welfare agency, the Department of Public Social Services. Under his leadership, the department not only kept up with a mushrooming caseload but also radically reduced its error rate in signing people up for food stamps.

“He is a turnaround artist. He’s proven his ability to take a troubled department and turn it around,” Yaroslavsky said, noting that Browning did not apply for the DCFS position but was sought out by the Board of Supervisors.

He hasn’t wasted any time in his new assignment, as he seeks to make over an agency plagued with a series of highly-publicized lapses in protecting vulnerable children under its care.

A dormant strategic plan has been reawakened, with thousands of the department’s 7,300 employees submitting suggestions for initiatives and action items. Browning expects many of them to volunteer to take on new duties as the plan turns into reality.

Meanwhile, monthly meetings with top managers have been shaken up in a big way, with statistics from each DCFS office beamed up onto two huge screens for all to see. It’s part of a “data dashboard’ approach that not only introduces some healthy peer pressure and accountability to the proceedings but also makes it easier for managers to exchange ideas for solving each other’s problems.

“It’s pretty interesting to see the discussion,” Browning says.

He’s also looking for ways to remake the department’s emergency response command post system, which struggles to place children, especially teens and infants, in safe situations after hours.

“They see so many kids late at night that are so difficult to place,” he says. While the overall issue is complex, some simple fixes might be possible—such as forming a foster parents’ association that could help identify families willing to take late-night placements, or providing diapers or extra money to families willing to take on the challenge of caring for an infant.

And he’s getting ready to reorganize. “I’m foreseeing some pretty significant changes,” he says.

When Browning came in as DCFS’ interim director in August, he was the department’s third interim director in nine months. The previous permanent chief, Trish Ploehn, departed amid an uproar over high-profile child deaths and questions about whether the department was being open with policy-makers and the public. Browning’s appointment to the $255,000-a-year post is effective Thursday, Feb. 16.

Browning has a master’s of social work degree, but acknowledges he doesn’t have a deep background in child welfare.

“I think my value is management,” he says. “I see myself as an implementation guy.”

He said that over the course of his career, a variety of assignments—from running a grocery store to managing units responsible for U.S. Navy reserve logistics—have given him the tools to get things done.

Even as he’s thinking big at DCFS, Browning is stressing a simple set of principles to his new workforce.

“Common sense, critical thinking and accountability: I think almost anything you do falls within those parameters,” Browning says. “I have to be accountable, and our staff has to be accountable.”

Posted 2/14/12

The new kids on campus

December 1, 2011

Throughout his 15 years, Mauricio hasn’t had much to celebrate, not with a turbulent family history that has led to a life of foster care and self-doubt. So when the call came, he couldn’t contain himself. “I was jumping up and down,” recalls the impish teenager.

Throughout his 15 years, Mauricio hasn’t had much to celebrate, not with a turbulent family history that has led to a life of foster care and self-doubt. So when the call came, he couldn’t contain himself. “I was jumping up and down,” recalls the impish teenager.

Mauricio had been informed that he’d been picked to participate in an unprecedented summer experiment on the UCLA campus, one that aims to infuse ambition and confidence into a group of kids who rarely go to college mostly because there’s been no one to help them get there.

Mauricio says he packed his suitcase a full month before the start of the intensive, five-week program and arrived so early on the first day that the former sorority house where he and the others would be living was still empty. “I was just so proud,” he says.

In a sense, however, the occasion represented more of a start than a finish. The students will continue to meet monthly on the Westwood campus and, if sufficient funds can be raised, will return in subsequent summers, along with new crops of recruits that will swell the program’s ranks and someday, hopefully, turn them all into full-fledged college students.

On Friday, that pride was shared by plenty of others—but, most importantly, by the 24 inaugural graduates of the First Star UCLA Guardian Scholars Summer Academy, the first such academic program of its kind for foster kids and others under the jurisdiction of child welfare officials. The youngsters, all of whom will be entering 9th grade, were honored during a commencement ceremony highlighted by one girl’s rousing exclamation: “I’m a Bruin now!”

In a sense, however, the occasion represented more of a start than a finish. The students will continue to meet monthly on the Westwood campus and, if sufficient funds can be raised, will return in subsequent summers, along with new crops of recruits that will swell the program’s ranks and someday, hopefully, turn them all into full-fledged college students. (Click here for a video on the program produced by Supervisor Yaroslavsky’s web staff.)

The program’s supporters say they’re determined to shatter the shameful statistics surrounding foster children, huge numbers of whom end up homeless and incarcerated in the years after their 18th birthdays, when they “age out” of the system. Only a fraction of them—an estimated two percent—continue their educations beyond high school.

“You can argue that college is their best possible ladder to leave behind a bad childhood and make it into a happy adulthood and a productive one that will not be a burden on the state, that will be something of high accomplishment,” says media executive Peter Samuelson, a driving force behind the program through his non-profit group First Star, which joined forces with UCLA and the County of Los Angeles.

“There’s nothing the matter with these children. Not one of them,” he says. “All of these kids can go to college. The issue is that nobody ever told them they could. How dumb is that? Who’s failing here, the kids or the grownups?”

The Summer Academy was designed to jump-start the participants’ collegiate careers and expose them to the rigors and culture of university life at a crucial juncture, just as they’re entering high school.

Each earned four college credits through a challenging mix of classes tailored to their educational, psychological and recreational needs. Those included math, literacy, social media, tai chi, cooking and life skills, where they learned meditation and conflict resolution. In the evenings, they were visited by an impressive series of speakers, including National Hockey League great Luc Robitaille, whose Echoes of Hope charity targets the needs of at-risk Los Angeles foster youth.

Each earned four college credits through a challenging mix of classes tailored to their educational, psychological and recreational needs. Those included math, literacy, social media, tai chi, cooking and life skills, where they learned meditation and conflict resolution. In the evenings, they were visited by an impressive series of speakers, including National Hockey League great Luc Robitaille, whose Echoes of Hope charity targets the needs of at-risk Los Angeles foster youth.

And then there were the field trips to, among other places, Disneyland, Skid Row and celebrity Chef Mario Batali’s restaurant, Mozza, where one teenage girl sheepishly confessed to eating nine slices of the establishment’s famed pizza. (The Batali Foundation also contributed money to the Summer Academy, along with the Stuart Foundation, College Board, Sage Publications and Hasbro Children’s Foundation.)

“It scares you in the right way,” Tiffany, 14, says of the program’s morning-to-night regimen. “You know what you’re being pushed to do. A lot of people say, ‘Oh, I want to go to college.’ But until you actually see college kids and what they do and their level of intelligence, it’s hard to say yes.”

Initially, 30 students were selected for the program. But six boys were sent home in the second week for bad behavior, a wrenching decision for all involved. Still, academy officials had no intention of joining the long line of adults who’ve abandoned or given up on such boundary-pushing kids, a reflection of the program’s commitment to—and understanding of—its charges.

Program leaders have remained in contact with the remorseful teens and have held out the promise that they can participate in the group’s monthly UCLA gatherings and, if all goes well at home and in school, they’ll be able to join next summer’s class of young scholars.

“They’ve been told, ‘You are fine young men.’ They’ve all been given hope and a shining pathway of behavior to get themselves back in,” says Samuelson, who raised $305,000 for the summer academy. “When we get these six young men back into the academy, they will count amongst our greatest successes.”

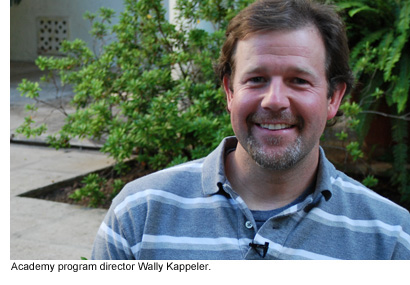

Day to day, the program is run by a seemingly unflappable educator and former vice principal of an elementary school in a tough New Jersey neighborhood. “I fell in love working with students who felt that nobody else cared about them,” says academy director Wally Kappeler, 37, the father of an eight-week-old son.

He says that, for him, the biggest surprise of the summer program was how quickly the kids were willing to open up, especially after an evening session when one of them broke the ice and shared the story of his mom’s death. “Here,” Kappeler says, “they have an opportunity to be heard.”

He says that, for him, the biggest surprise of the summer program was how quickly the kids were willing to open up, especially after an evening session when one of them broke the ice and shared the story of his mom’s death. “Here,” Kappeler says, “they have an opportunity to be heard.”

Kappeler says another boy, shy and self conscious about his weight, would mostly keep to himself like “an outcast” until he was given a special daily job of locking a rear door at their three-story Hilgard Avenue house after deliveries by the caterer.

“He felt so proud that this was his responsibility that he volunteered for all kinds of jobs,” Kappeler says. “He volunteered to take the trash out to the dumpster and wipe the tables and make Kool-Aid for the entire group. And it became contagious…It’s amazing the inspiration that he’s been to us, coming out of his shell and taking a leadership role without saying much of anything at all.”

Because of such breakthroughs and the upbeat bonding between the youngsters, it’s easy to forget the circumstances that brought them to UCLA—the abuse and neglect, the revolving placements in new homes and schools, the philosophies of life that have evolved from the sadness of their situations.

Listen, for example, to Eddie, a soft-spoken 15-year-old, who confides: “Too much happiness could actually hurt you. You just need the right amount because I don’t want to get hurt anymore. Right now I’m not really in the mood for situations like love and happiness. I really want to succeed in my life.” Eddie says he’s determined to be the first in his family to attend college.

Or hear what Thalia, 14, has to say as she speaks for the many who’ve been betrayed by parents. “Even if they’ve done something bad to you, they’re still your blood and they’re part of you and you love them no matter what. And you will always forgive them, even though you’re mad at them at the moment. But they’re always going to be in your heart.”

Kappeler says his heart aches when he hears the kids talk like this. “The emotional baggage they’re holding onto is the stuff that most adults would use as an excuse to give up on life.” Instead, Kappeler says the academy is teaching students to harness the power of their narratives through writing, video and social media so they can become more effective advocates for themselves.

“I want them to feel like they can make a difference in this world just by being who they are and getting their story out,” he says, noting that each was given a laptop and video flip-cam to keep.

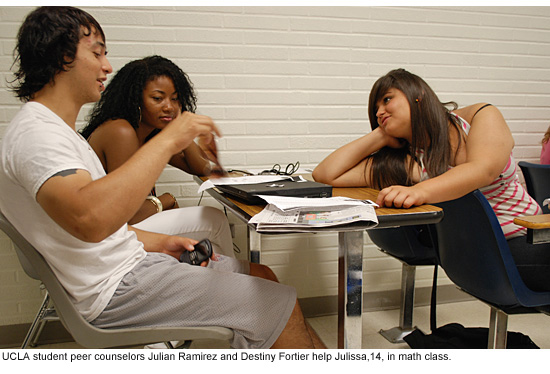

To guide and inspire the participants along the way, the program was staffed by peer counselors and resident assistants who are UCLA students and, for the most part, former foster youths themselves.

One of was senior Julian Ramirez, 21. As a youngster in San Jose, he endured a home fraught with addiction and violence. “One day my dad would say, ‘Let’s go fishing.’ The next, he’d be beating us with the fishing poles.” Under a mop of dark hair, Ramirez says he’s still got a scar from a concrete slab his father smashed against his head. Child welfare authorities, he says, repeatedly removed him and his siblings from his parents.

In his senior year of high school, Ramirez says it was “do or die” and he began to excel, achieving a 4.0 and becoming the captain of the wrestling team. He went to a community college in Cupertino—despite several months of homelessness—and then transferred to UCLA, where he joined the UCLA Bruin Guardian Scholars, a campus association of former foster youth. “What mattered to me most,” he says, “was that I wanted to stay on track with my peers. I didn’t want to be slower than them. And I wanted to prove to myself I was capable.”

In his senior year of high school, Ramirez says it was “do or die” and he began to excel, achieving a 4.0 and becoming the captain of the wrestling team. He went to a community college in Cupertino—despite several months of homelessness—and then transferred to UCLA, where he joined the UCLA Bruin Guardian Scholars, a campus association of former foster youth. “What mattered to me most,” he says, “was that I wanted to stay on track with my peers. I didn’t want to be slower than them. And I wanted to prove to myself I was capable.”

He says he hopes that his empathy and success—and that of the other student staffers—proved useful to the young teenagers in the summer program.

“I’ve been through a lot,” he says. “I know how it is to be 14, angry and not have anyone to talk to.”

In fact, the young participants told UCLA researchers late last week that the student mentors were “really impactful for them,” especially in the way “they talked about their journey through foster care,” says Associate Professor Todd Franke of the School of Public Affairs/Social Welfare, who’s conducting a longitudinal study of the students’ progress.

Franke says that, although it’s too soon to say much definitively about the program, there are some encouraging signs, based on a comparison of initial interviews with the teens and another series conducted on the eve of their commencement.

From the beginning, Franke says, virtually all the students said they wanted to go to college. “But in the past five weeks, the vast majority now see it as a much more realistic goal. It moved them further down the continuum to think that this is a real possibility for them.” They got a sense of the workload, learned that they’d likely be eligible for financial aid and came to believe that they’d have a strong campus support group to help get them through the rough patches, according to Franke. “The process,” he says, “was demystified.”

From the beginning, Franke says, virtually all the students said they wanted to go to college. “But in the past five weeks, the vast majority now see it as a much more realistic goal. It moved them further down the continuum to think that this is a real possibility for them.” They got a sense of the workload, learned that they’d likely be eligible for financial aid and came to believe that they’d have a strong campus support group to help get them through the rough patches, according to Franke. “The process,” he says, “was demystified.”

On Friday, commencement day, an assortment of foster parents, legal guardians and relatives gathered around dozens of tables inside UCLA’s Tom Bradley International Hall. There, they heard speeches about the heart and hope of the young Summer Academy participants. Among the officials who addressed the teens and their caregivers was Los Angeles County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, whose office helped facilitate the program through the Department of Children and Family Services.

He told the teenagers that, on some level, he could identify with their struggles. He said his mother died when he was 10 and that his father worked in the evenings, which meant there was no one to help him with homework or keep an eye on him at night.

“The thing that you have that most college students don’t have is that by the time you get ready to come into college, you probably will have gone through the toughest part of your life,” said the supervisor, a UCLA alumnus. “And while you may not appreciate that, you should embrace that experience, treasure that experience, because it’s going to toughen you up. It’s going to make you tough enough to confront whatever comes along your way, when you’re in college and after that.”

After the speeches were done and the two-dozen scholars received their graduation certificates—along with a standing ovation—it was time for them to leave this place of grownup aspirations and youthful good times. There were lots of hugs and tears, even though they’ll all be together again on campus in a month.

“I feel proud but at the same time I feel sad,” explained Mauricio. “I feel like this is my house.”

Video and photos by Supervisor Yaroslavsky’s web staff.

Posted 8/7/11

Audit reveals flaws in children’s agency

October 26, 2011

More than a dozen years ago, California voters, by the slimmest of margins, passed a measure championed by actor/director Rob Reiner imposing a 50-cents-per-pack tax on cigarettes to infuse huge sums into programs aimed at lifting the lives of children 5 and under.

More than a dozen years ago, California voters, by the slimmest of margins, passed a measure championed by actor/director Rob Reiner imposing a 50-cents-per-pack tax on cigarettes to infuse huge sums into programs aimed at lifting the lives of children 5 and under.

“This is a sweet victory,” Reiner elatedly proclaimed after a final tally of absentee ballots had given his Proposition 10 the edge. “It means so much for the young children of this state…”

But this week in Los Angeles, the mood was far more somber as the Board of Supervisors received a highly critical audit of how hundreds of millions of dollars of that money has been administered locally by an independent public agency called First 5 LA.

Although no malfeasance was uncovered, the board was so concerned about the findings that, by a 4-1 vote, it set in motion a plan to strip First 5 LA of its independence and turn it into a county agency, like the majority of its companion organizations across the state.

The audit, requested by Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich, who’s currently serving as chairman of the First 5 LA commission, was performed by Harvey M. Rose Associates and bluntly details a series of risks that the firm says may be undermining the performance and integrity of First 5 LA. Among the findings:

- First 5 LA has been significantly under-spending its revenues, placing the organization “at risk of not fulfilling its mission and goals to the extent possible and consistent with the Board of Commissioners policy and program objectives.” With a fund balance of more than $800 million, the organization has spent comparatively less on its programs than California’s other First 5 groups.

- The First 5 commission receives such insufficient information from the organization’s staff that its ability to oversee spending, program activity and outcomes is compromised. “Most grant and contract awards, representing hundreds of millions of dollars of annual agency expenditures, are not submitted for approval or review.”

- In the last fiscal year, the agency awarded more than $200 million in contracts, but failed to report them all to the First 5 commissioners, which “raises the risk of agreements being in place for inappropriate purposes or with unqualified vendors or grantees.” In fact, the commission approved only 28% of First 5 LA contract awards. In many cases, contracts were awarded without competitive bidding—and without notifying the commission. Auditors could not determine how some contracts were awarded because documentation was not properly retained.

- The staffing of First 5 LA is high compared to other First 5 agencies and is “not configured to best enable development and administration of new programs and initiatives,” thus contributing to the under-spending problem and delays in launching health, safety and educational programs for the county’s children.

- During the past four fiscal years, First 5 LA has had an annual staff turnover rate ranging from 8 to 19 percent a year, generally higher than other First 5 organizations surveyed by the auditors. This, along with the absence of a commission-approved compensation policy, “raises the risk of First 5 LA not being able to attract and retrain qualified, high-performing employees.”

After the audit findings were presented during Tuesday’s Board of Supervisors meeting, Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky offered a particularly blunt assessment.

“The lack of transparency, the lack of accountability, the lack of competition in proposals, the lack of information sharing between the staff and the commission itself, any one of these things would be a bell and whistle. And all of them together is a siren,” said Yaroslavsky, who praised Antonovich for initiating the audit process.

No representatives from First 5 LA testified during Tuesday’s session. But the organization’s chief executive officer, Evelyn V. Martinez, later released a statement noting that, since 1998, First 5 LA has undergone annual independent audits of its financial statements and controls “and at no time have these audits resulted in any material findings.”

First 5 LA, she said, “takes its fiduciary responsibilities seriously and has been a responsible caretaker of the public funds entrusted to it.” While acknowledging the Board of Supervisors’ authority to exert greater control over the organization, Martinez said that “I hope we can continue to maintain our focus on improving the lives of our youngest children in Los Angeles County.”

Among chief executives of First 5 commissions in California’s 58 counties, Martinez’ annual compensation of nearly $250,000 in 2009-2010 topped the list. That included a $10,000 performance bonus.

Supervisor Gloria Molina cast the sole vote against the motion authored by Antonovich and Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, which directs the county counsel and chief executive officer to prepare a proposed ordinance establishing First 5 LA as a county agency and report back within 30 days.

“I don’t see where one dollar was stolen, one dollar was misappropriated, one dollar was mishandled,” said Molina, who was chair of the First 5 LA commission during some of the audited period. (That position is held by the sitting chairman of the Board of Supervisors, a position that rotates annually. Each supervisor also appoints a member to the commission.)

Molina added: “I think it’s a shame that we are moving so drastically to take over this agency.”

The audit process began earlier this year when the governor proposed diverting half of the current and future Proposition 10 tobacco-tax money from the county commissions established to administer it. For First 5 LA, according to the Antonovich/Ridley-Thomas motion, this would divert about $450 million from its current reserves and $50 million annually in the future.

The audit, conducted in two phases, initially was intended to identify First 5 LA’s reserves and ensure the most efficient use of future allocations. But, in the end, serious issues were uncovered that led to Tuesday’s vote.

The First 5 commissions have sued the state to block diversion of funds. The case is pending.

Posted 10/26/11

The Browning of DCFS

August 10, 2011

Philip Browning’s wife was, to put it kindly, skeptical when her husband told her that he’d been tapped to temporarily take control of Los Angeles County’s deeply troubled Department of Children and Family Services. “Why,” she asked, “would you want to take on a situation like that?”

Philip Browning’s wife was, to put it kindly, skeptical when her husband told her that he’d been tapped to temporarily take control of Los Angeles County’s deeply troubled Department of Children and Family Services. “Why,” she asked, “would you want to take on a situation like that?”

After all, Browning had emerged as one of the county’s most innovative and effective executives while running the huge Department of Public Social Services, which provides safety-net services for more than 2.6 million people on the economic margins of society.

Browning’s answer to his wife, who used to be a child protective services worker, was simple and direct: he was jumping into the DCFS pressure cooker because the Board of Supervisors asked him to do so.

“I was in the military for a long time and was accustomed to being asked to do things not entirely of my own choosing,” says Browning with a hint of his Southern gentility. “I think I have a sense of obligation.”

With the board’s official and unanimous vote for Browning this week, he becomes DCFS’ third interim director in the past nine months, following the dismissal of permanent chief Trish Ploehn amid an uproar over a number of high-profile child deaths and questions about the department’s forthrightness.

Browning was selected by board members who’d grown so dissatisfied that they retook control of the department’s management several months ago from the chief executive office, which had been given that responsibility as part of a sweeping remake of county government in 2007.

Although Browning is an interim director, the board has made it clear that they do not want just a seat-warmer while a search is underway for a permanent boss. He is empowered to take the actions necessary to improve the agency’s performance, as he has done at DPSS, making it among the nation’s leaders in serving its clients.

Whether at DPSS or DCFS, Browning says he offers a consistent approach. “The goal is to hire qualified people, get them trained and hold them accountable.” He says he knows that, for some managers, that final piece—accountability—can be uncomfortable.

“It’s tough to take the difficult disciplinary actions. We let people stay in positions where we know they should be moved,” says Browning, recalling times that he’s recommended the dismissals of longtime DPSS employees for violating client confidentiality or committing other serious transgressions.

That said, Browning is known as a team builder—more inclined to motivate than criticize. He also is legendary for his reliance on statistics to gauge an operation’s effectiveness. “Without good data,” he says, “you can’t change a program.”

At DPSS, he says, “we measure everything that is possible to be measured.” Those numbers are then analyzed monthly in a formal setting by managers.

“When I first came to DPSS, it was a very scary process,” Browning says of those sessions. “People would throw up before the meeting. The prior administration was more into criticism. It put too much stress on our employees. I just changed the focus. I told them we are all in this together. Let’s share our secrets of success. Let’s don’t try to be so competitive.”

Late Tuesday, after the board’s vote, Browning sent a memo to DCFS employees. He knows that some of them undoubtedly will be questioning the wisdom of selecting someone not currently immersed in Los Angeles’ child welfare system.

So he wrote of his masters of social work degree and the many years he spent in human services in Alabama and later in Washington, D.C. He recounted his 2001 hiring to turnaround a Los Angeles County District Attorney operation that had been widely criticized for failing to aggressively obtain child support money from so-called deadbeat dads. As the first director of child support services, his office increased collections 36% to $500 million and, he wrote, “moved the agency from a law enforcement system to a human services culture with a priority on customer service.”

Then, after talking about his belief in data, accountability and wellness programs (“I ran my five miles today,” he noted), Browning closed by saying that “the work performed by DCFS is some of the most challenging in America and…will certainly be a challenge to me.”

“I need your help and support.”

Posted 8/10/11

It’s not easy being Mom

May 5, 2011

Mother’s Day means flowers, candy, hugs and a full court press at Hallmark. But for many new moms in Los Angeles, becoming a mother is no brunch at the Ritz.

Data from the latest “Los Angeles Mommy and Baby Survey,” published by the county Department of Public Health earlier this year, show that despite some positive news on breast-feeding, prenatal care and post-delivery checkups, there’s trouble in Momville.

From depression to dental woes, unplanned pregnancies to prenatal obesity, the survey offers what can only be termed a mother lode of insights into new motherhood in L.A.

First, the good news. “Over 90% of the women in L.A. County receive prenatal care, which is spectacular compared to other parts of the country,” said Dr. Diana Ramos, the county’s director of reproductive health, who noted that Medi-Cal has helped to ensure that low-income women in California are covered during pregnancy. Also, 85.2% of the mothers surveyed had breastfed their babies and 98.3% took their newborn in for a well-baby check-up.

Now for the not-so-good.

The countywide survey, which canvassed 6,264 new mothers who gave birth in 2007, found that 58.1% of new mothers surveyed said they were at least a little depressed after giving birth, and 19.9% said they had been depressed for a period of two weeks or more during their pregnancies.

The countywide survey, which canvassed 6,264 new mothers who gave birth in 2007, found that 58.1% of new mothers surveyed said they were at least a little depressed after giving birth, and 19.9% said they had been depressed for a period of two weeks or more during their pregnancies.

“One of the things that is quite startling is the number of women who experience depression,” said Cynthia Harding, director of Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health Programs for the public health department, which produced the survey.

“It says that we need to provide more social support,” Harding said. “Pregnancy is a time of joy, and if you’re not feeling the joy, you might feel ‘What’s wrong with me?’”

To that end, a multifaceted push is on to increase awareness of maternal depression, reduce the stigma and train health care and other providers to better recognize the symptoms. This brochure is being distributed this month to new mothers in all hospitals across the county.

“It’s a very, very vulnerable time,” said Caron Post, director of the L.A. County Perinatal Mental Health Task Force, which is spearheading the “Speak Up When You’re Down” campaign with the Department of Public Health. “Mothers put on a happy face. It’s taboo to be depressed and be a mother.”

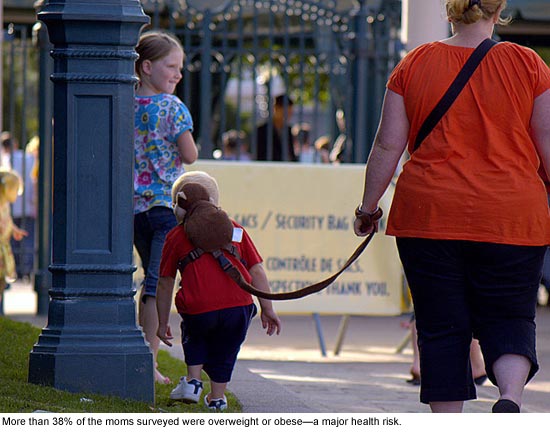

Obesity is also a big concern.

More than 38% of the mothers surveyed were overweight or obese before getting pregnant, and more than a quarter said they didn’t exercise during pregnancy.

“If there was any one call to action, it would be obesity. It’s one of the big risk factors in maternal mortality,” Dr. Ramos said. “Yes, we all know there’s an obesity issue. But I don’t think we’re doing enough to give directive advice [on keeping weight down] to reproductive age women.”

There’s also room for improvement when it comes to pre-pregnancy preparedness.

For instance, 53.4% of the new moms surveyed said their pregnancies had been unwanted or “mistimed,” and 34.1% said their husband or partner shared those views.

What’s more, 70.7% received no preconception health counseling and 54.4% didn’t know about the importance of taking folic acid supplements before and during pregnancy. And 9.6% smoked in the six months before becoming pregnant.

What’s more, 70.7% received no preconception health counseling and 54.4% didn’t know about the importance of taking folic acid supplements before and during pregnancy. And 9.6% smoked in the six months before becoming pregnant.

Not exercising during pregnancy was by far the most common “risk behavior,” reported by 28.6% of those surveyed. But other risks showed up, too, including drinking alcohol (10.5%), exposure to second-hand smoke (6.3%), smoking (2.6%) and using illegal drugs (2.4%).

In the 3rd District, women who participated in the written survey reported high rates of breastfeeding and well-baby check-ups. They were the least likely to have been overweight prior to pregnancy—and the most likely to have received fertility treatment.

They also were the likeliest to drink alcohol during their pregnancies, 12.4% compared to 10.5% countywide. Any level of drinking during pregnancy is of concern to public health officials. “It may be two or three weeks before you realize you’re pregnant. If you want to get pregnant, stop drinking ahead of time,” said county maternal programs director Harding.

Another painful finding: dental distress.

Nearly 19% of those surveyed (21% in the 3rd District) said they’d experienced periodontal disease during pregnancy. Many women can’t find a dentist who’ll treat them, especially during pregnancy, while others are fearful and put off going until the pain is unbearable, advocates said. In either case, tooth and gum infections can present a serious medical risk for mother and fetus when bacteria enter the bloodstream.

The survey is part of the Los Angeles Mommy and Baby Project, which was launched following an increase in infant deaths in the Antelope Valley, mostly among African Americans, from 1999 to 2002. After an initial 2004 pilot survey in the Antelope Valley, the project was expanded countywide in 2005.

A new survey of women who gave birth in 2010 is currently underway, and is expected to capture stresses inflicted by the current economic downturn.

“We are seeing more and more patients who have lost their health insurance but don’t qualify for any low-income programs,” said Debra Farmer, president and CEO of the Westside Family Health Center in Santa Monica.

Even among the 2007 moms, 36.7% said they had no insurance, 22.4% reported stress over unpaid bills, 13.8% were stressed out over job loss experienced by their husband or partner, and 11.6% over losing their own job.

There are concerns that as California moves to implement health reform—and to cope with a drastic budget situation—that cutbacks will diminish the level of maternity services available to those who need them most.

“I think a lot of what has been there in the past is eroding because of the economic situation and the state cutbacks,” said Lynn Kersey, executive director of Los Angeles-based Maternal and Child Health Access. “What’s going to happen during health reform is of extreme interest.”

Spring forward to summer camps in L.A.

April 7, 2011

Summers can be a challenge for young families, but there are some great day camps and enrichment programs out there—if you register in the spring.

Summers can be a challenge for young families, but there are some great day camps and enrichment programs out there—if you register in the spring.

That’s the secret that Southern California parents often learn the hard way, usually as panic sets in a week or so before school ends. Fortunately, space is still available at many local day camps and enrichment programs, including some offered by Los Angeles County.

Here’s just a sample of L.A.’s many options. Sign up soon—summer will be here any day.

–Adventures in Nature Day Camp at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County is still open to kids from kindergarten to sixth grade between July 11 and August 12, from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. Activities range from astronomy to trips to the La Brea Tar Pits. Kim Kessler, who is handling camp registration, says a few of the weeks are sold out for younger children, but most still have space—for the moment. Each week costs $250 per child for museum members, $300 for non-members. Click here to get your little nature lover in on the action or call 213-763-3348.

–The Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s popular summer art camp for children filled up within 24 hours after registration opened this year. But if your young artists are teenagers, they’re still in luck. LACMA offers four workshops for teenagers, and they still have openings. Weeklong classes run from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. in digital photography, mixed media or painting. A month-long workshop focuses on building an art portfolio. Shorter workshops cost $200 a week for members and $225 for non-members. The longer workshop costs $650 for members and $750 for non-members. Click here for an enrollment form or enroll at the museum box office at 323-857-6010. Questions? Call 323-857-6139.

–There’s still room, for the moment, at the Los Angeles County Arboretum’s popular Summer Nature Camp, which offers full or half-days, with extended care starting at 8 a.m. and ending at 5 p.m. Kids aged 5-10 can plant trees, learn to cook from the garden, do arts and crafts, learn about bugs or just explore the Arboretum’s lush 127 acres in Arcadia. The camp runs in one-week sessions from June 3 through Aug. 12. Full-day sessions are $300 a week for members and $335 for non-members; half-day sessions are $150 and $168, respectively. Need more information? Click here or call Ted Tegart, youth education coordinator, at 626-821-5897. Or sign up at 626-821-4623.

–The Mountains Restoration Trust offers yet another day camp for little nature lovers in the Santa Monica Mountains, operated from the 1896 Calabasas farmhouse that now houses the non-profit’s nature center. Susan Haugland, project manager for youth programs, says the Discovery Nature Camp, for kids 8-12, is particularly hands on, with lots of cool guests speakers, field trips and appearances by skunks that can do the moonwalk. Hours are from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. Monday through Friday, and a weeklong session costs $260. Enrollment is capped at 18 children per week, but registration just opened. Sign up at 818-591-1701 x212.

–The Dolphin Camp and other water awareness camps offered in the past by the county’s Departments of Beaches and Harbors were cancelled this year due to budget issues. But the Los Angeles County Junior Lifeguard Program is still alive and well, sponsored by the Los Angeles County Fire Department. The summer program, offered in half-day morning or afternoon sessions, instructs kids in ocean skills from swimming and surfing to water safety. It’s open to kids aged 9-17 who pass a swim test; pre-registration begins April 25 for the May 7 test in Manhattan Beach. The 5-week program starts June 27. Last year the fee for the summer-long program was $420, but a $56 increase is pending before the Board of Supervisors. For more information, click here or contact the Junior Lifeguard Office at 310-939-7214 or [email protected].

– Registration opens May 3 for the summer day camp at the county’s El Cariso Park in Sylmar, which is open to kids aged 6-12. The camp starts July 1 and lasts until the Friday before school starts in September and—working parents will like this—it goes from 7:30 am to 6 p.m., Monday through Friday. There’ll be field trips, arts and crafts, computer classes and outdoor playtime, plus swimming and sports fundamentals. The price is right, too: $65 a week, plus a $20 registration fee. Sign up at the park office next to Mission College at 13100 Hubbard St. in Sylmar, or call 818-367-7050.

– Want to make a movie? This summer, the William S. Hart Park and Museum and Los Angeles County Arts Commission will offer a free three-day filmmaking workshop for kids aged 10-17. Students will learn about filmmaking, theater, and storytelling, as well as the legacy of local silent film star William S. Hart, as they create their own silent film. The workshop will be taught by instructors from the Canyon Theatre Guild and the CalArts Community Arts Partnership. Space is limited and applications are required. Hours will be 10 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. on July 23, July 30, and August 6. For more information, call 213-202-5858.

–Does a short course in horn playing, tap dancing or classical piano sound fun? The Colburn School in downtown Los Angeles is offering summer camps in all three. The Colburn Academy Festival, a 2-week program, is limited to highly gifted young pianists, but the Tap Intensive, at the school’s downtown Studio B at 200 S. Grand Avenue is open to beginning, intermediate and advanced hoofers from 7-19 during the week of June 27-July 1. And the Horn Camp, a 4-day workshop, is open to horn players of all ages. Need more information? Call 213-621-1085 for the Tap Intensive, 213-621-4554 for the Horn Camp or click here for the piano program.

–The Hollywood Bowl doesn’t do camps, but it does offer a great summer outing for kids and parents (or day care providers) weekday mornings from July 5 to August 12. For just $7 per ticket, kids can watch a concert in the museum patio area, do some fine arts activities and make a morning of it. Or bring a picnic lunch and stay into the afternoon. The Summer Sounds Series will feature classical Korean music for the first two weeks, gospel music for the second two weeks and Irish dance and music for the final two weeks. Click here for more information. Tickets go on sale May 14.

Posted 4/7/11

This is how the county rolls

March 6, 2011

Back in September, the Department of Public Social Services began fighting hunger where it lives by using a mobile unit to help people sign up for food assistance. During the the next few weeks, it’ll be headed into Hollywood and the San Fernando Valley.

Back in September, the Department of Public Social Services began fighting hunger where it lives by using a mobile unit to help people sign up for food assistance. During the the next few weeks, it’ll be headed into Hollywood and the San Fernando Valley.

The Health and Nutrition Mobile Services Unit essentially is a traveling DPSS office, complete with computers and staffers to help with paperwork. Its mission is a crucial one, especially in these challenging economic times.

Only about half of eligible county households currently are enrolled in the CalFresh program, formerly known as food stamps. This means government funds are going untapped and families are going without help to meet their basic nutritional requirements.

The Mobile Services Unit has begun to make a dent in the disparity. It has distributed more than 700 applications, with 430 of them being returned as of last week.

Although its primary work is to bring CalFresh to those who need it, the unit also will offer other services, including help with Medicaid applications. Various community groups are providing the venues for the DPSS truck and supplying their own services.

This month, the Health and Nutrition Mobile Services Unit will be in the Third District at three locations. They are:

Friday, April, 8, from 9 a.m. to 2 p.m.

Los Angeles City College – Mini Resource Event

4311 Melrose Ave., Los Angeles, 90029

Wednesday, April 20 from 9 a.m. to 2 p.m.

Van Nuys Worksource Center – La Mission College

11623 Glenoaks Blvd., Pacoima, 91331

Saturday, April 30 from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m.

Canoga Park Farmers Market & Community Health Fair – at the Community Center

7428 Owensmouth Ave., Canoga Park, 91303

Posted 4/6/11

She’s got the toughest temp job in town

January 12, 2011

Three months ago, Antonia Jimenez was the new kid on the block in Los Angeles County’s Chief Executive Office.

Three months ago, Antonia Jimenez was the new kid on the block in Los Angeles County’s Chief Executive Office.

Today, she’s at the helm of one of the county’s most challenged departments, one with a mission second to none: saving kids’ lives.

As the newly appointed interim director of the Department of Children and Family Services, Jimenez has been thrust into a job in which leadership decisions can have enormous real life consequences, with every wrong move getting a very public airing.

Jimenez is just two weeks into the job but already is confronting longstanding trouble spots and dishing out straight talk about what’s wrong—and right—with the department she’s been charged with running since the reassignment of former director Trish Ploehn.

“You have great, great social workers,” Jimenez said in her first in-depth interview since taking the interim director’s job. “I don’t think there’s a lack of talent there. But within that are the mediocre ones who never should have been social workers in the first place.”

Such “problem workers” figured into a review of the department that Jimenez oversaw before assuming her new post. That analysis, released in November, also found: significant backlogs in cases requiring emergency responses; time-consuming and often unfocused mandatory training sessions for administrators, and a welter of “duplicative or contradictory” policies that make it harder for social workers to do their jobs effectively.

Jimenez—who says she’s not permanently pursuing the top job—is realistic about what she can fix as an interim director.

“I’m very honest with the staff. Kids will die, unfortunately…But no kid should die because we haven’t done our job,” she says.

Jimenez, 49, was born in Puerto Rico, grew up in Manhattan and had a two-decade career in Massachusetts state government and several years in the private sector before county CEO William T Fujioka hired her in September as a $215,000-a-year deputy CEO.

As the deputy coordinating and overseeing issues involving children and families, Jimenez didn’t have the luxury of slowly breaking in. She found herself on the front lines of the internal turmoil and public outrage stemming from a series of highly publicized deaths of children who’d had earlier contact with DCFS.

Now that she’s on the inside, she recognizes even more the urgency of getting up to speed.

“You always have a learning curve,” she says. “I have done this little listening tour, and I need to do more.” Doing more includes additional ride-alongs with social workers and observing department hotline and command post operations up close.

One of her top priorities, she says, is to tackle a backlog of emergency cases that have not received action for more than 30 or even 60 days, despite the potential dangers this poses to children. She plans to increase staffing in the seven regional offices with the highest backlogs—particularly in three that account for 50% of the overall total. Jimenez says she’s not only reassigning and transferring employees, but also bringing in “experienced temps” for 120 days “to really focus on this problem.”

In the next few weeks, she’ll also be focusing on the hotline, the first point of contact with the department when a child’s safety is at risk.

She says she will examine staffing levels and the experience of hotline employees, with the aim of making sure that calls that need prompt attention get it and are not placed behind those that can wait a little longer. The goal: “We deal with ‘immediate’ immediately.”

Jimenez, who’s living in Redondo Beach with a friend until she can find the time to get her own place, understands that someone in such a sensitive position must take strong action and cannot simply be a caretaker until a permanent replacement is found. (Read Zev’s blog on what he believes the department needs in a new leader.)

Jimenez acknowledges that the upheaval in the department, culminating with Ploehn’s departure, has been tough on the staff. But it’s also been difficult for her, she says.

“I didn’t come to Los Angeles to remove a director. That wasn’t my job,” she says. “The transition for them, the transition for me, was also hard.”

Posted 1/12/11

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink