Top Story: Social Services

Helping homeless families heal

November 24, 2014

Gabriele Gonzalez was living a hard life last winter. She was homeless and addicted to methamphetamine, sleeping in parks and abandoned buildings, unsure where she’d find her next meal.

Today, she’s headed in a dramatically different direction. She lives in a comfortable room in a freshly-refurbished residential treatment center, has a new job in customer service, and is looking forward to a possible reunion with the three children—aged 6, 8 and 10—who were taken away from her when she was at her lowest point.

Her transformation has not been a solo voyage. Crucial assistance is coming from the Via Avanta Residential Center in Pacoima, where a pilot program called “Project 60: Women and Children” is underway to help homeless women, particularly mothers, with serious mental illnesses.

The program marks the latest extension of Project 50, a pioneering “permanent supportive housing” program launched by Los Angeles County in 2007. It provided 50 of the most vulnerable homeless people on Skid Row with housing first, and then surrounded them with mental healthcare, substance abuse treatment and other services. Project 50-style programs have since expanded to assist nearly 1,000 people across the county, said Mary Marx, who oversaw the initial effort for the Department of Mental Health. The initial investment paid off, too—saving $4,774 per person over the first two years by keeping them out of jails and emergency rooms. And the model has spread to cities including Denver, San Francisco and Washington, D.C.

And, of course, to Pacoima, where for many in the women’s pilot program, the well-being of their children serves as a powerful motivator to turn things around.

“I had lost apartments, cars and jobs before, but I had never lost my kids,” said Gonzalez, 29, whose son and two daughters were removed last November by the Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services and placed with relatives. “When they got taken, I lost a big part of me. I couldn’t imagine having them grow up with the idea that I didn’t fight for them.”

At a court date last January, Gonzalez realized that she was running out of time to get her kids back. Motivated to take action, she turned to a list of help numbers provided by DCFS and decided to call Via Avanta, which is run by Didi Hirsch Mental Health Services. She moved in on February 5, 2014.

Kita Curry, president and CEO of Didi Hirsch, said that having children involved presents special challenges and raises the stakes of the housing program.

“We’re not just helping an individual get their life together; we’re helping a family get their future together,” Curry said. “Otherwise, these kids would be at risk of trouble at school, getting in bad relationships and repeating the cycle.”

Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky—an early supporter and pioneer of the housing-first approach—identified $542,000 in 3rd District homelessness funding to refurbish one of two residential buildings at Via Avanta last year. Last month, he directed an additional $1.7 million to the facility to redo the second building.

Though only a year old, the women’s program already is making a difference. It has served 39 women since the beginning of 2014. All were homeless and suffered from severe mental illness. Many also came with substance abuse disorders. Some, like Gonzalez, no longer had custody of their children. Others were admitted with children in tow. So far, 16 have been discharged and 23 remain in treatment. Of those discharged, 88% went on to live in supportive housing or with spouses, family and friends. Half moved out with their children and the others continue to work toward reunification.

Unlike Project 50—which dealt with single homeless people, most of them men—this program must consider the safety of the children and the realities of parenting, Curry said. Raising kids can be stressful even without mental health issues and substance abuse challenges, so it’s important to ensure that the women can cope with those realities before they are discharged.

After moving in, Gonzalez felt an immediate sense of security knowing that her basic needs would be met. She began putting her life back together, piece by piece—going to group therapy sessions, working in the kitchen and attending classes on subjects such as parenting, safety, domestic violence and relapse prevention.

“At first I was very emotional,” Gonzalez said. “I would cry in every group. It was part of my healing process.”

After a month or so, Gonzalez was allowed to have visitors, but she first needed to mend the bridges she had burned with members of her ex-husband’s family, who have custody of her children. The kids now visit occasionally, and Gonzalez has tea parties, plays dress-up and reads to them. She’s seen them “about 10 or 11 times. I’ve had to sit back and be OK about the fact that I’m not going to get as many visits as other people, but I‘m doing what I can.”

In addition to working on mental health and substance abuse issues with counselors, she built a resume and did mock interviews at Chrysalis, a nonprofit employment agency that works with Via Avanta. After spending hours each day applying for jobs at the work center’s computers, three weeks ago she was hired to do customer service for online companies. She wakes at 4 a.m. each day to commute from Pacoima to her workplace in Glendale. In her spare time, Gonzalez plays piano and even sings in Via Avanta’s hallways. Her current favorite is “Someone Like You” by Adele.

Gonzalez is adamant about taking responsibility for her life, but, like many homeless women, she also must come to terms with a long series of youthful traumas, including rape, molestation and abuse. By 15 she was diagnosed with clinical depression. Married at 18, she spent the next 12 years in a troubled relationship and turned to drugs, she said, to deal with her inner pain.

At first, she was reluctant to accept help in coming to terms with her past.

“I guess I held that stigma that I’m crazy if I have to see a therapist,” Gonzalez said. “I was very anti-medication. But it made such a difference. The medication and therapy has helped me so much.”

Now she’s looking ahead to the new year. February looms as an important month. That’s when she expects to move from Via Avanta (the program is generally geared to short-term stays) and has a custody hearing scheduled on the 15th.

“Hopefully that will be the date that I reunite with my kids,” she said.

Someday, Gonzalez hopes to attend nursing school and help other women like herself, perhaps at a place like Via Avanta. But she doesn’t want to get ahead of herself. She planes to continue focusing on her mental health and substance abuse issues by staying in treatment and going to 12-step meetings.

“I’ve put in a lot of work but none of it would have been possible if I hadn’t come here,” Gonzalez said. “I’m looking at life in a new way. I love myself today.”

Posted 11/21/14

Heroism forged in pain

September 11, 2014

Ambyr Rose descended from generations of drug-addicted mothers whose children ended up in the foster care system. She, however, overcame that legacy of abuse and neglect and now helps broken families become whole again.

On Tuesday, Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky named her the 3rd District’s Family Reunification Hero, citing her work in the Department of Children and Family Services’ Parents in Partnership program.

“Her passion for encouraging others to engage in recovery and to find their way towards reunification with their children is what set her apart,” Yaroslavsky said.

This was the fifth year for the Family Reunification Hero awards, which honor individuals, families, organizations and agencies who’ve made significant contributions towards helping children return to their homes and families. Every year, each member of the Board of Supervisors awards a scroll to the hero chosen for his or her district.

Rose, a 31-year-old Sylmar resident, said her traumatic experiences have strengthened her resolve to restore families torn apart by drug abuse, alcoholism, domestic violence, poverty and other reasons.

“I think the reason I went through everything I did is so that I can help others, make a difference in their lives,” she said. “I truly, honestly, believe that we all have a purpose, and this is mine.”

Rose’s resilience helped her break her family’s cycle of tragedy and despair.

Her grandmother, a heroin addict, killed herself while playing Russian roulette. Her mother, orphaned at a young age, entered foster care and also became hooked on drugs.

Rose bounced around from foster home to foster home until aging out of the system. She also suffered from sexual abuse.

Trying to dull her pain, she reached for the same stuff that ruined her mother and grandmother.

“Crystal meth was my drug of choice but I used anything, really — anything to fill a void, anything to numb myself,” Rose said.

By age 21, she was homeless and the mother of three young children.

“We were sleeping in the stairwells of buildings, in cars, basically any spot that we could find a place,” Rose said. “I hit rock bottom in 2005 when my youngest, who was 18 months old, had pneumonia for the third time and had to be hospitalized.”

She decided to “call DCFS on myself,” prompting social workers to place her children in a foster home in Palmdale.

Over the next year, Rose remained a slave to her drug addiction and didn’t once call her children, thinking they were better off without her. But when a court moved to terminate her parental rights so her children could be adopted, Rose checked into rehab.

She was then pregnant with her fourth child.

Rose stayed sober and learned job skills through the Via Avanta Residential Center in Pacoima, obtained housing through the federal Section 8 program, and childcare support and other aid through CalWorks.

Rose was reunited with her children in 2007.

Almost a decade after she hit “rock bottom,” Rose remains sober, is close to earning a degree at a community college and works for DCFS as a “parent partner.” Her two oldest children are both honor students.

“She’s magnificent,” said 27-year-old Shelly Sor of Northridge, who is trying to regain custody of her children after being accused of not doing enough to help a son with a behavioral disorder.

“If Ambyr hadn’t given us the tools, the support, I think we would have failed completely,” Sor said. “If she hadn’t been there, I think we would have given up.”

Rose’s fellow parent partner, Ryan Bennet, nominated her as a Family Reunification Hero.

“The biggest thing about Ambyr is her attitude,” Bennett said. “She’s always looking for solutions, always willing to keep fighting.”

Posted 9/11/14

Rescuing youthful identities

August 14, 2014

L.A. County is working hard to repair the finances of foster kids whose credit has been abused by adults.

Minors are ineligible for credit cards and car loans in California. Yet there they were—the names and Social Security numbers of more than 100 Los Angeles County foster children on credit reports dating back years.

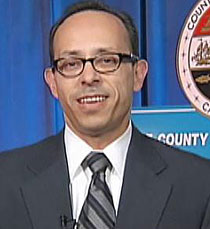

The discovery, part of a 2010 pilot survey on identity theft in the foster care system, was a wake-up call, recalls Rigoberto Reyes, chief of investigations for the county Department of Consumer Affairs, which helped conduct the survey.

Some of the most vulnerable children in the county were being exploited so duplicitous adults could obtain apartments, vehicles, jobs, cell phones, gym memberships, health care, even mortgages and bail money.

“In one case, a prostitute had gotten hold of the foster kid’s information and was using the kid’s name every time she was arrested,” Reyes says. “To clear it, we had to get the kid a letter from the Department of Justice’s identity theft registry.”

The study, launched in the wake of a 2006 state law aimed at curbing identity theft in the foster care system, has since grown in Los Angeles County into a protection effort unmatched anywhere else in the state.

Now, with a number of legal and procedural kinks worked out of the system, Consumer Affairs has formally teamed up with the county Department of Children and Family Services to add routine credit checks to the list of services the county performs for its foster children, scouring credit databases for children’s names and clearing them as needed.

“Identity theft is rampant when it comes to foster children,” says Sasha Stern, an attorney with the L.A-based Alliance for Children’s Rights, which provides free legal services to children in out-of-home care. “They move so much, and their personal information is transferred so many times that they’re just more vulnerable. So what the county is doing is great.”

Working through a secured web site with the credit bureau Experian, the two county departments this year have begun routinely checking and clearing the credit records of every foster child over 16 in the county system, quietly troubleshooting one of the most common—and pernicious—obstacles to the children as they age out of the system and attempt to start lives as independent adults. By November, the county also will begin working with the two remaining major credit bureaus, Equifax and TransUnion.

“Imagine trying to rent an apartment, or buy a used car, if you’ve been stuck with bad credit,” Reyes says. “And now imagine trying to do that if you’re a foster kid, dealing with all the worries foster kids have when they’re being emancipated.”

“Often these kids don’t find out there has been a fraud until they’re denied a student loan or a car loan,” adds DCFS Division Chief Harvey Kawasaki. “Or until an employment agency does a credit check on them as a prospective employee, and then decides not to hire them.”

Although California passed a law in 2006 aimed at clearing foster kids’ credit records, implementation has been slow because of procedural and funding woes. Most counties still do little more than crosscheck the names of their foster children with credit databases, leaving the children themselves to rectify any problems.

But L.A. County has its own in-house consumer affairs staff, as well as about half of the foster children in California. That, Reyes says, is why L.A. was chosen for the 2010 pilot, which checked the records of about 2,110 foster children.

In the last four years, Reyes says, the county has checked the credit of 8,126 foster children, finding that about 10 percent of them had open accounts under their names. That’s significantly higher than the prevalence of identity theft among adults in the general population, which is about 7 percent, according to a 2012 federal study.

“It’s not a lot of kids, but those who do have problems have multiple, multiple problems,” Reyes says.

The fraudulent accounts seemed more likely to be opened by relatives or acquaintances of the children than by their foster families, Reyes says, and most involved credit cards, utilities or medical care. “For example,” he says, “we had one where the sister delivered a baby in the emergency room and used the foster kid’s ID because she didn’t have insurance, and our kid got hit for the bill.”

Some cases also point to lax quality control among lenders. One recent survey of names, for instance, turned up more than 50 credit card accounts that had been opened at one major bank under foster kids’ identities, presumably with social security numbers that would have identified them as minors.

So far, no fraud has been prosecuted through the program. This is partly because the checks until now have involved thousands of names at a time, with an emphasis on clearing up the credit records, as opposed to punishing wrongdoers. But abuses are expected to get more scrutiny as caseloads lessen.

Under the formalized system underway this summer, the names and Social Security numbers of each foster youth will be compared twice with the credit bureaus’ records—once right after the children turn 16, and again, shortly before they turn 18. Consumer Affairs will then clear up any problems.

“About 175 of our foster kids turn 16 every month,” Reyes says. “So even assuming that 10 percent have problems, that’s fairly manageable.”

Even so, he warns, separating fraud from human error isn’t easy. Sometimes the record is as simple as confusing a son’s name with a father’s, or clearing up a credit bureau’s mistake.

In the case in which a $217,000 mortgage was found on a foster child’s credit record, for instance, investigators couldn’t determine whether the loan had deliberately been taken out under the youth’s name or whether the credit bureau had simply erred.

One of the biggest hurdles authorities face, Reyes says, is the reluctance of foster children to press charges against their betrayers.

“We had one where the father was using the kid’s information, and when the city attorney sat down with the kid and told him the process, he stopped returning our phone calls—he didn’t want to confront the father. He was afraid of the guy.

“That vulnerability is one of the hardest things about these cases, but also why they’re so important to resolve.”

Posted 8/14/14

Picking up pace to protect kids

July 3, 2014

David Sanders and Leslie Gilbert-Lurie are moving from the blue ribbon panel to a new transition team.

As Los Angeles County prepares to hire its first-ever child protection czar to lead an ambitious new oversight program, efforts to build that system accelerated this week with the appointment of a high-profile transition team to help get the initiative off the ground.

The nine-member team approved by the Board of Supervisors on Tuesday includes a mix of newcomers as well as several veterans of the Blue Ribbon Commission on Child Protection, which earlier this year urged the county to create an Office of Child Protection as the cornerstone of a wide-ranging package of reforms.

The transition team is charged with sifting through more than 40 of the commission’s recommendations to help prioritize which the county should implement first.

David Sanders, who chaired the blue ribbon panel and also will be a member of the transition team, said a big part of the interim group’s job will be to make sure that proposed reforms receive the necessary follow-through.

“We really have concerns about that…We didn’t want to just add a new series of recommendations,” said Sanders, a former head of the county’s Department of Children and Family Services who now is an executive vice president of the Seattle-based Casey Family Programs.

The team, which is meant to disband once the Office of Child Protection is up and running, will also help recruit and shape the job description for the person who will run the new agency.

In addition, the transition panel is charged with making some critical assessments in the days and weeks ahead. For one thing, it will evaluate the performance—and potential for expansion—of the county’s network of so-called medical hubs, where the physical health of youngsters coming into the system is evaluated. And it will wade into the sometimes contentious issue of how best to use county nurses to help social workers conduct frontline investigations of suspected child abuse.

The transition team will provide monthly updates to the Board of Supervisors beginning on August 5.

The reforms now being implemented come after the horrific death last year of Gabriel Fernandez, an 8-year-old Palmdale boy was left by social workers in the care of his mother and her boyfriend despite multiple reports of abuse, neglect and torture.

Even before the blue ribbon commission began its work, current DCFS head Philip Browning had embarked on a reform mission from within the department, including expanded training, a plan to hire more staff and reduce caseloads, creation of a foster care search engine, and a new data-driven approach to making the agency function more effectively. Those efforts continue as the transition team’s work gets underway.

In addition to Sanders, transition team members who also served on the blue ribbon commission include Andrea Rich, Leslie Gilbert-Lurie and Janet Teague.

The newcomers include Dr. Mitchell Katz, the county’s director of Health of Services, along with former Los Angeles County District Attorney Steve Cooley, Supervising Dependency Court Judge Margaret Henry, Patricia Curry of the county Commission on Children and Families and Antonia Jimenez of the county’s Chief Executive Office.

Sanders said the group represents a rich mix of professional knowledge and L.A. County experience.

“I couldn’t be more excited,” he said. “I think it’s really a remarkable team.”

Posted 7/3/14

‘Unseen, unheard and unsafe’

April 11, 2014

Blue ribbon commission chair David Sanders,center, at the meeting Thursday, with Leslie Gilbert-Lurie, left, and retired judge Dickran M. Tevrizian.

Los Angeles County’s child protection system is broken and demands immediate fixes, according to a draft of a new blue ribbon commission report that paints a troubling portrait of dysfunction, secrecy and largely ineffectual struggles to turn the tide on decades of tragedy and trauma.

“On our watch, many of Los Angeles County’s most vulnerable children are unseen, unheard and unsafe,” the report says in its opening sentence. “In eight months of hearing hundreds of hours of testimony, the commission never heard a single person defend our current child safety system.”

The panel issued numerous recommendations, including creation of a powerful “child protection czar”—a single entity responsible for coordinating child welfare efforts across departmental boundaries and reporting directly to the Board of Supervisors.

The commission’s report, approved Thursday in its draft form, will go before the Board of Supervisors on April 22, with a longer follow-up discussion set for May 20.

Philip Browning, head of the Department of Children and Family Services since 2012, said he agrees with some of the report’s assessments, including a finding that persistent turnover in DCFS leadership over the years has “devastated morale and created endless directives.” He said he welcomes the report’s recognition that it takes an array of departments and agencies—not just DCFS—to protect kids.

“The concept of having everybody be responsible is certainly a good one. The problem is…any time we get a new set of recommendations, we do have to pull people off doing whatever they’re currently doing to respond to those recommendations.”

Browning said he wishes the commission had acknowledged recent progress within the department, including a dramatic expansion of training, a plan to hire more staff and reduce caseloads, creation of a foster care search engine, and a new data-driven approach to make DCFS operate more effectively.

“I was a little surprised that they didn’t look more closely at our strategic plan, the first one in 10 years,” Browning said. “A lot of things that they’re talking about are already included in our strategic plan.”

The 10-member commission started work following the death of Gabriel Fernandez, a Palmdale boy who died last year following numerous reports of abuse, neglect and torture. The Board of Supervisors was divided about the necessity of creating the blue ribbon panel in the first place; Supervisors Zev Yaroslavsky and Don Knabe said they wanted to let reforms initiated by Browning have a chance to take root before adding more recommendations to the hundreds that have piled up over the years.

But in the end, all five supervisors appointed members to the panel, including retired judges, a social work educator, advocates for children and families, and a former head of DCFS, commission chair David Sanders.

The commission held 15 public hearings in which it heard testimony about “overwhelming” caseloads, infants spending hours on desks because of a foster home shortage and young people who can’t trust or even reach their social worker.

The draft report depicts a county bureaucracy lurching from crisis to crisis yet failing to coordinate among departments that should be working together. Budget and planning processes are opaque, and communication among those seeking to help children is “needlessly” hampered by various perceived confidentiality restrictions that end up hiding problems instead of correcting them, the report said.

In short, there is “a state of emergency that demands a fundamental transformation of the current child protection system,” the commission found.

It said the Board of Supervisors needs to take action immediately. Commissioners noted that they had provided the board with an interim report in December that included recommendations that could have been implemented at once.

“Since then, another 5,000 referrals of child abuse and neglect have been investigated without the benefit of systemic reform,” the report said. “Each day we wait for reform, 40 more infants are reported as possible victims of abuse or neglect.”

Members of the blue ribbon panel, meeting Thursday at the Hall of Administration, unanimously voted to recommend establishment of a single entity that would oversee all aspects of child protection in the county and have the authority to channel resources across bureaucratic boundaries to get things done.

But commissioners were divided on how best to accomplish that. A majority said a new agency, which could be called the Office of Child Protection, should be formed. But three commissioners said it would be preferable to work within the system and give enhanced responsibility to an existing entity to guide the process.

For his part, DCFS chief Browning said “the devil is in the details” about how such a system would operate.

“I would really like to see somewhere that has worked well. It’s a novel concept,” Browning said. “It’s going to be a potential issue if someone has the authority to move money without much oversight…I would be surprised if the board would give up their authority to do that.”

Beyond its call for placing a single powerful entity in charge, the blue ribbon commission also found that, despite responding to years of crises, the county has failed to establish a clear child protection mission with measurable goals: “The board must mandate that child safety is a top priority,” the draft report said. “It must articulate a child-centered, family-focused countywide mission.”

Part of that mission should focus on protecting children before abuse can happen—something that so far has all too often taken a backseat to reacting to an onslaught of high profile cases, the commission said. That should include pairing public health nurses with social workers on home visits involving infants, creating an “early warning” alert process within the county’s information-sharing Electronic Suspected Child Abuse Reporting System, and focusing intensively on those at highest risk.

“Children reported to DCFS prior to age one are at the highest risk for later serious injury or fatality,” the report said.

The report is still being revised, but this link, posted by KPCC, offers a look at the work in progress prior to Thursday’s meeting.

Posted 4/11/14

A Cinderella moment

March 27, 2014

Foster teen Lisa Slayton gets a makeover at last year's Glamour Gown extravaganza. “It was like a blessing,” she says. “Fabulous.”

It was an invitation that another teenager might have taken for granted. Alexx Solyom had been asked to her first winter formal, a masquerade ball in January at Pasadena’s posh Brookside Country Club. It was her senior year. The entire Class of 2014 would be there.

“But I’d been in foster care for about two and a half years,” the 17-year-old said, “and I was living from foster placement to foster placement. I couldn’t afford a dress—I was in a group home and there weren’t enough funds.”

Enter Pam Bingham, the court-appointed special advocate for Alexx, who knew about a program just for girls in her situation. Within days, the teenager was heading home with a free, brand new, floor-length dress.

Their fairy godmother? Glamour Gowns, a collaboration between CASA of Los Angeles and hundreds of volunteers—many veterans of show business—who believe that girls in the foster care system should, like any girl, get to feel like Cinderella on prom night.

“It was a black and white dress, a long dress with crystals going around the front,” says Alexx, recalling how Bingham had kept it at her house in San Gabriel until the big night so it wouldn’t end up being damaged or vandalized in the group home.

“I felt like a princess.”

Now in its 13th year, Glamour Gowns is gearing up this week for its largest-ever Cinderella moment, an event that on Saturday will offer a free prom outfit and day of beauty to some 500 high school girls in foster care.

Initially launched by a handful of volunteers with a few dozen cast-off dresses, Glamour Gowns has since outfitted thousands of foster girls for proms, homecoming dances and winter formals. Its signature spring event, geared to prom season, has become such an annual extravaganza that the Los Angeles Convention Center now houses it.

Sponsors include: Chinese Laundry, which donates new shoes; Jenette Bras, which custom-fits each girl with appropriate foundation garments, and D.J. Bronson Inc., a Commerce-based apparel manufacturer that over the past five years has donated more than 5,000 new dresses—and, occasionally, tuxes—to grateful foster girls.

Meanwhile, members of I.A.T.S.E. Motion Picture Costumers Local 705, Costume Designers Guild Local 892 and Theatrical Wardrobe Union Local 768 donate their time, as do hair and makeup stylists.

“I know to some people it might sound frivolous, but it absolutely isn’t,” says Jennifer Parker-Stanton, a former costumer for film and TV who has been involved in nearly every Glamour Gowns event since its founding.

More than 28,000 children are under the jurisdiction of the dependency court in Los Angeles County and more than 17,000 live in foster care. Often, Parker-Stanton says, their caretakers can’t—or choose not to—afford “non-essential” yet emotionally important items like prom regalia. As a result, she says, girls in foster care often simply opt out of key adolescent milestones rather than risk more disappointment in a life that often is already painful.

“This is about self-esteem,” says Parker-Stanton, whose costuming work ranged from the TV series “Nash Bridges” to the Academy Award-winning “Million Dollar Baby”.

“The first time I did this, the girl I was working with looked in the mirror and said, ‘People say I’m pretty, but until now, I never thought so.’ And I thought, ‘All this time that I’ve spent running around, shopping for famous people, when you can change a life with just one dress.’”

“It’s a social experience that the girls never forget,” agrees Michael Williams, a veteran social worker with the Department of Children and Family Services who has seen at least five of his young clients transformed by the program. “Most of them have never gotten this kind of attention before. “

Anissa McNeil, a Glamour Gowns Committee member and CASA of Los Angeles board member, says the teenagers are often most surprised to see that the outfits are department store-quality merchandise, not hand-me-downs or seconds.

“They’re like, ‘You mean I get to keep this?’ And we say yes. ‘And it’s all new?’ Yes,” McNeil laughs. “One girl made me pinky promise one year that everything was free.”

McNeil says, the group makes sure no one leaves empty-handed.

“Last year, we had a plus-size young lady and she didn’t see any dresses she liked that were the right size, and you could just see her thinking, ‘Nothing ever works for me.’ She was saying, ‘Thanks for inviting me, I’ll just take a purse if that’s okay,’ when the seamstresses came in and…made a gown for her, right there on the spot. When she tried it on, and it fit like a glove, the look on her face—well, there wasn’t a dry eye in the house.”

McNeil says the event is particularly rewarding for her because she, too, spent time in foster care. “My mother had a nervous breakdown, and my brother and I became homeless when I was six,” she remembers. “Our grandmother raised us and became our legal guardian.”

Today, McNeil has a doctorate and a practice as an educational consultant, but remembers keenly the challenges that face foster children. She had to work two jobs in high school to pay for her prom dress, she says, and because she is over six feet tall, it had to be specially tailored. Then, on the big night, her date failed to show up.

“Hey, that’s what happens when you go for a playboy,” she recalls laughing. “But as my brother and I tell people, if you can overcome being homeless, you can overcome anything. I was determined to go, and I went by myself—in a gown that was long and blue and elegant.”

Posted 3/27/14

Reinventing DCFS

August 8, 2013

Philip Browning, at a community meeting, is leading the charge to transform DCFS from within. Photo/L.A. Times

Despite the highly-publicized creation of a blue-ribbon commission to investigate potential flaws in Los Angeles County’s child protection system, the Department of Children and Family Services already is in the midst of a sweeping transformation aimed at boosting the beleaguered agency’s effectiveness and accountability.

The breadth of the year-long effort was disclosed publicly for the first time this week by DCFS Director Philip Browning during a presentation before the Board of Supervisors. Appointed less than a year ago by the board, Browning has spearheaded the department’s first strategic plan in a decade—“an adventure,” he calls it—revamping everything from the training and deployment of social workers to the creation of a database identifying children with the greatest levels of instability in their lives.

And, as he did while previously heading the county’s Department of Public Social Services, Browning has brought a statistical sensibility to virtually all facets of DCFS operations, holding managers accountable for achieving quantifiable measures of effectiveness. At the same time, he’s worked closely with, and sometimes bucked, the department’s union to keep more experienced social workers on the front-lines, where they can better protect children in potentially abusive homes.

In recent weeks, concerns have been expressed by some officials, including Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, that the board-appointed Blue Ribbon Commission on Child Protection might slow the department’s momentum by making burdensome demands on the agency during the panel’s six-month examination. But the commission’s newly-installed chairman, former DCFS Director David Sanders, insisted in an interview last week that he’s sensitive to the potential for distraction and expects the panel’s work to focus more broadly on the network of agencies entrusted with protecting the county’s children.

In fact, the non-profit Casey Family Programs, where Sanders is now a top executive, is helping DCFS streamline a 6,000-page policy manual that staffers rightly complained was impossible to penetrate, Browning said during his presentation before the board this week, noting that the rewrite was one of numerous “game changers” underway. Among the others:

- Creating a radically different training program for incoming social workers. The curriculum at six local universities that channel social workers to the county is being standardized, revamped and expanded from 8 weeks to 52, with an emphasis on “much more critical thinking and much more real life experience,” Browning said. A key element is being created at USC, where a stage set depicting a roach-infested house in a gang-dominated neighborhood is under construction. Social workers in training will interact with a cast of role-playing adults and children in simulated real life situations, as professors and other students observe the action from behind a one-way mirror.

- Devising an unprecedented data-driven model for customizing social worker caseloads. Previously, caseloads remained largely uniform throughout the department’s 18 field offices. But under Browning’s direction, the agency has created a statistical formula that takes into account the prevalence of certain risk factors among children served by each office. Under the “caseload equity” initiative, social workers in offices with the highest risk scores will be given fewer cases, allowing them to devote more attention to children facing the greatest dangers.

- Preventing emergency response staffers from transferring to new posts after a year. Browning, to the consternation of some of the agency’s unionized social workers, has imposed a freeze on the longtime practice of front-line workers transfering after a single year. These jobs are among the agency’s most demanding and stressful, involving life-and-death decisions about whether to leave children with their families or remove them. Although the union contract allows workers to request such transfers, Browning says he made a “management decision” to block the practice because children were being ill-served by the chronic turnover and brain drain. He’s now pushing for a three-year minimum assignment.

- Developing and implementing a “high risk database” to identify children who need more intensive intervention. Using data mining techniques, the department created an algorithm, believed to be the first of its kind anywhere, that weighted various factors—including how often a child runs away, has a psychiatric hospitalization or moves to different homes—to find those among the 35,000 children in its care who are the most unstable and at risk of aging out of the system into homelessness, joblessness and despair. They are then targeted for an array of tailored treatment services. Browning said 100 high-risk children already have been provided more permanency and stability with a family member, a foster family or a group home.

During his presentation, Browning acknowledged that, while progress has been made, it’s only a start. And he gave the board an example from his world to consider. From their desktop computers, he told the supervisors, “you can see any hotel in the world. You can see what the pool looks like. You can make a reservation.”

But when it comes to using a search engine to find an available home for a foster child, he said, “we can’t do that well in Los Angeles County. We can’t tell if there’s a vacancy for a 2-year-old. That’s something we’ve been working on…and I think we’re going to get there.”

Posted 8/8/13

Another hard look at DCFS

July 25, 2013

A blue ribbon panel will investigate the vast network of agencies responsible for keeping children safe.

An independent commission created as Los Angeles County’s latest effort to keep children safer in its sprawling child welfare system took final shape this week, as the Board of Supervisors named the last four appointees, ranging from child advocates to the former head of the county’s juvenile court.

The appointments to the Blue-Ribbon Commission on Child Protection rounded out a 10-member panel established after the May 24 death of Gabriel Fernandez. The 8-year-old Palmdale boy was left by social workers in the care of his mother and her boyfriend despite multiple reports of abuse, neglect and torture.

The mother and boyfriend are being held on murder charges and several employees have been placed on desk duty pending results of an internal investigation at the Department of Children and Family Services.

In the wake of that case and others, however, a majority of the supervisors also believed that that the child protective system needed a deeper examination by an independent investigative body modeled after the Citizen’s Commission on Jail Violence, which last year recommended reforms after disclosures of deputy brutality in the county lockup.

Former DCFS Director David Sanders, appointed by Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, said in an interview that the panel will have a broad mandate to investigate the network of agencies that interact in the child welfare system, including law enforcement and schools.

“This is a full, countywide, responsibility and not just a DCFS responsibility,” Sanders stressed in an interview. “What’s most critical is to understand very specifically how many children are being seriously injured due to abuse and neglect. What are the numbers of fatalities? How many children are being re-injured after they come to the attention of the agency? And how can the county improve safety for children?”

Retired Judge Terry Friedman, appointed by Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, said the panel will need to distinguish itself from earlier investigations that have led to management shakeups and hundreds of recommended reforms.

“It’s something we need to address—are we different or are we just the next installment of a longstanding litany of good-intended efforts?” Friedman said. “And if not, how do we approach this issue differently?”

One challenge the commission will face, he added, is the belief that, with the right set of solutions, child deaths can be halted altogether in a system as big and complex as Los Angeles County’s.

“That isn’t to say we can’t make it less likely,” said Friedman, whose 15 years on the bench included stints as the supervising judge for the juvenile dependency court and presiding judge for the juvenile court.

“But realistically, the challenges are so embedded in our society that the best one can hope for is to recognize possibilities and limitations and be realistic in order to make some progress, rather than pretending that perfection is possible.”

Friedman was named to the panel on Tuesday, along with Leslie Gilbert-Lurie, a founding board member and past chair of the Alliance for Children’s Rights and a former member of the Los Angeles County Board of Education, and Janet Teague, who has served both on the Alliance board and on the Los Angeles County Commission for Children and Families. Also appointed this week was Gabriella Holt, a former member of the Los Angeles County Board of Education and a current member of the Los Angeles County Probation Commission.

Like Friedman, Gilbert-Lurie was appointed by Yaroslavsky. Supervisor Don Knabe appointed Holt and Teague.

The four completed a series of earlier appointments that included:

- Marilyn Flynn, dean of the USC School of Social Work, appointed by Ridley-Thomas.

- Richard Martinez, a former foster youth who is superintendent of the Pomona Unified School District, and Andrea Rich, former president of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, both appointed by Supervisor Gloria Molina.

- Dan Scott, a recently retired veteran of the Sheriff’s Department’s Special Victim’s Bureau, and DickranTevrizian, a retired U.S. District Court judge, both appointed by Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich.

Among the more intriguing picks was Sanders, who oversaw DCFS from 2003 until 2006. Now based in Seattle, he left to become executive vice president of systems improvement for a national foundation specializing in foster care, the Casey Family Programs.

Since his departure, the department has had five directors and acting directors, with the latest turnover occurring last year, when veteran county executive Philip Browning agreed to take over. Browning—who had overhauled the county’s child support efforts and the Department of Public Social Services—was implementing a new strategic plan and training curriculum at DCFS when the Fernandez death was disclosed.

“It’s a tough job,” Sanders said, adding that he hopes the commission will focus on the big child protective picture “rather than interfere or kind of rehash issues that have been examined multiple times.”

“The demands on the department can be quite daunting,” he added. “But I think Phil is somebody who has a lot of experience in the county, and I hope the commission can augment his work and take some of the pressure off him for issues that are really countywide.”

Posted 7/25/13

Bringing star power to mental health

July 9, 2013

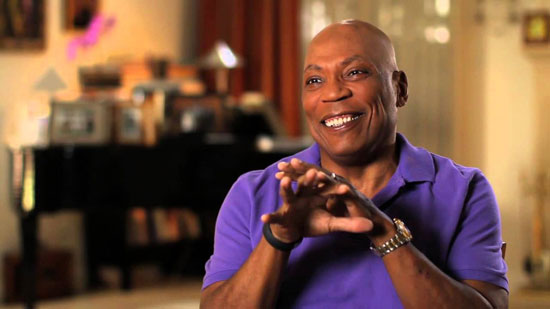

“Profiles of Hope” lets celebrities like producer/director Paris Barclay share how they overcame emotional pain.

It started as a handful of inspirational stories, shared by a few brave volunteers—how this one found help for depression, or how that one dealt with the fear of being labeled “mentally ill.”

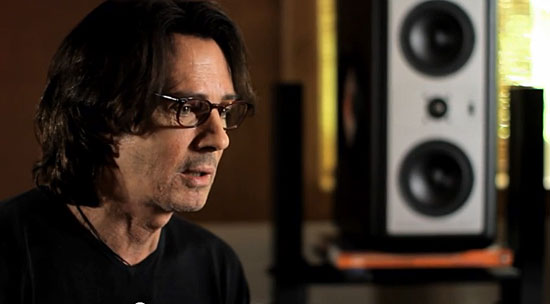

Three years later, “Profiles of Hope,” the Department of Mental Health’s online video series, has become an unlikely hit as a public health campaign. Celebrities such as Rick Springfield, Mariel Hemingway and Paris Barclay are sharing their personal stories. Last year, it won a local Emmy in the information/public affairs series category. And on Thursday, the mental health department announced that 60-second versions of the videos have been nominated in this year’s public service announcement category. Meanwhile, a half-hour show comprised of the segments just wrapped its second season on KLCS-TV, the Los Angeles Unified School District’s public television station. And most recently, “Profiles of Hope” has been discussed as a training tool for counselors in the Cal State University system.

“A lot of people have sent emails about how much this has moved them,” says the acclaimed Barclay, who directed and produced much of the award-winning HBO series, “In Treatment.” “More importantly, they’ve also shared their own stories, which is the real goal—to start the conversation. One person reveals what’s happened to them, and another person comes back with their story. It’s part of the human process, the circle of revelation.”

The Department of Mental Health’s public affairs director, Kathleen Piché, said the goal of the videos is “to bust the stigma of mental illness, and not just by hearing from providers and clinics and the usual suspects.” The segments came about in 2010, she says, shortly after the creation of the Los Angeles County Channel. “They asked us if we wanted to do some programming,” Piché recalls.

At the time, she says, the Department of Mental Health was looking for new ways to help people overcome the shame and fear that often accompanies emotional and psychological problems.

“A lot of people say they resist getting help because they’re afraid of how others will see them,” Piché says. “But the earlier people get help, the better their outcomes, and right now, the average length of time from the time people first get symptoms to the time they get help is about 10 years.”

Piché says she initially saw the videos as a series of “day in the life” documentaries that would help viewers realize how many people suffer from some form or another of mental illness. Eventually, she settled on shorter, more intimate testimonials. “There are obviously issues about privacy,” she says. “But there are also people who want to talk about it.”

The department already had an informal speakers roster, as did the National Alliance on Mental Illness, she noted, and after a few calls, she found three current or former department clients willing to share their stories.

Myra Kanter, a nurse and patient’s rights advocate, spoke about her lifelong struggle with depression. Isaiah Hinnerichs, a client at the time in a county program for transitional-aged foster youth, talked about the mental health care that helped lift him out of homelessness. Gary Gougis, now a peer advocate at the Department of Mental Heath, talked about the panic attacks that for years had crippled his ability to function.

“At the time,” Piché says, “nobody knew how impactful they would be.”

Since then, she says, more than a dozen Profiles of Hope have been produced, featuring testimonials from people as disparate as a champion boxer, a combat veteran and a gay Vietnamese refugee. Most popular, however, have been the testimonials of celebrities talking about the ways that they’ve been helped by good mental health care.

Actress Mariette Hartley discusses her family history of suicide and alcoholism. Maurice Benard of “General Hospital” talks about managing his bipolar disorder. Robert David Hall of “CSI: Crime Scene Investigation” talks about how he summoned the emotional strength to rebuild his life after both his legs were amputated in the wake of a car crash. Rock musician Springfield shares his story of overcoming depression.

In addition to the 10-minute taped interviews, which are available on Facebook, YouTube, the County Channel and the DMH web site, shorter versions are being aired as public service announcements.

The spots, which initially were paid for by the County Channel, now are underwritten by funds from the Mental Health Services Act, which taxes income over $1 million to support mental health programs. Each testimonial costs about $13,000 to produce, says Piché, who’s been assisted by DMH Public Information Officer Karen Zarsadiaz-Ige.

But to their audiences, the spots are priceless.

“I think Profiles of Hope was so amazing,” one viewer recently wrote to the department, conveying a special thanks to Barclay for sharing the story of his battle with depression and alcohol. “Recently I recovered from a depressive episode.”

“Rick, thank you for this. THANK YOU,” another commented on Springfield’s YouTube public service announcement.

Next up, Piché hopes, will be a series of interviews with well-known people in politics, sports and public service. Meanwhile, Araceli Esparza, who coordinates Mental Health Services Act programs for the California State University system, says the videos are under consideration as a mental health resource for trainings and workshops on the system’s 23 campuses.

“This just keeps growing,” Piché says. “But I think people are willing to do this because they know that it works.”

In rock musician Rick Springfield's video, he reveals his battles with depression and suicidal thoughts.

Posted 6/20/13

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink