Top Story: Transportation

Dial M for Metro WiFi

February 25, 2014

Hold the phone: after years of study, a project to bring WiFi and cellular service to L.A.’s subway system is now underway.

The project is on track for completion by January, 2016. But Daniel Lindstrom, Metro’s manager of wayside communications, said that work will likely take place in stages, with segments of the system—such as stations in the downtown L.A. business district—potentially coming on line earlier.

Work began in January. For now, they’re dealing with what Lindstrom calls the “techie stuff,” like where to locate a 2,000-square-foot “base station hotel” that will house equipment for cell phone providers that join the Metro network.

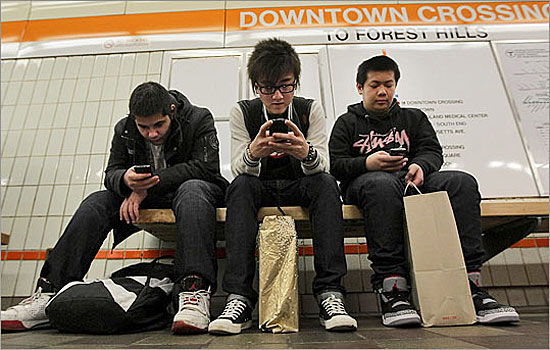

The company chosen to develop and operate Metro’s system, InSite Wireless, has already brought WiFi and cell service to Boston’s decades-old subway system, known as “The T.”

“If you can implement it in a 100-year-old subway, you can definitely implement it on a modern system like ours,” Lindstrom said.

Lindstrom said he could not estimate how many people will use the service when it is up and running in Los Angeles, but noted that there is particularly strong demand among younger passengers, whereas older riders tend to have more of a take-it-or-leave-it attitude.

“If you’re in your 20s, like my kids, they say, ‘Why don’t you have cell phone coverage in the subway? What’s wrong with you?’ ” Lindstrom said. “I’m just about to hit 50, and I think it’s nice to have but I don’t necessarily expect it. And if you’re in your 80s, you say, ‘Just forget about it.’ ”

Riders of the Red and Purple subway lines won’t be the only beneficiaries of the new service; it will also cover below-grade portions of the Blue, Gold and Expo lines, along with the future Crenshaw Line.

Lindstrom said that people with data plans through their individual cell phone service will be able to use their devices on Metro free of charge. Those who don’t have such plans will pay as they go when they sign into the network on a platform or in a subway car, much as they currently do on airplanes—or in other underground systems around the world.

“London makes you pay $3 a day,” Lindstrom said.

Lindstrom said Metro is hoping to offer an early taste of what the system will offer by having Union Station’s WiFi up and running by its 75th anniversary later this year.

When the whole system is online, Metro will receive at least $360,000 a year from the program, and its share of revenue from InSite could potentially be far greater. A report last year to the agency’s Executive Management Committee said that Bay Area Rapid Transit in northern California reported $2 million a year in new revenue after it installed cell and data service.

The service also will enhance security by enabling passengers to call for help if needed. And, Lindstrom said, it will allow sheriff’s deputies and security officers to view and respond to real-time video feeds.

“It’s a force multiplier,” Lindstrom said. “It will allow deputies to see things as they are going on.”

Posted 2/21/14

Metro’s hardest seat to get

February 13, 2014

Despite a city-owned public toilet, Metro gets complaints of public urination at Pershing Square station.

As the saying goes, “When you gotta go, you gotta go.” That’s true whether you’re in a restaurant, a concert hall or riding a subway. But, despite public demand, installing restrooms at Metro stations is no easy business, according to the transportation agency, which recently undertook a study of the issue.

“We want to ensure that our customers have a great riding experience and have resources when a need arises, but there are a lot of elements that have to be factored in,” says Debra Johnson, Metro’s interim chief operating officer.

Although the agency has been grappling with the issue of public restrooms for years, Metro’s Board of Directors ordered a new look in November after residents near the Pierce College Station of the Orange Line busway in the San Fernando Valley complained that some riders were urinating in public. Among other things, Metro installed a video camera and monitored the area for 30 days, but couldn’t corroborate those complaints.

At the same time, the agency also was asked to take a look at the potential need for publicly-accessible restrooms at subway, light rail and bus rapid transit line stations throughout the system. The bottom line, according to a report that will be presented to the board later this month: Increasing the number of restrooms would not only be costly but could create crime problems unless security is enhanced at each location.

Currently, Metro maintains public toilet facilities at Union Station, the El Monte Bus Terminal and the Harbor/Gateway Transit Center—transportation “hubs” where staffers are present at all times. According to employee observations, restrooms in the busy Union Station were used consistently throughout the day. At the El Monte facility, five or fewer customers lined up during peak hours to use the free-standing automated public toilet, with less use at the Harbor/Gateway center.

The report notes that Metro employee restrooms are in place at Red Line subway stations but are opened to the public only in emergencies, as determined by Metro personnel. Generally, the report said, “customers are informed no public toilets are available,” even though it’s not uncommon for Red Line riders at the large 7th Street station to ask about the availability of public restrooms.

The agency, in its report, acknowledged the unpleasant realities that confront customers at some stations.

“Metro’s custodial staff report on-going issues with public urination and defecation at several of the rail stations as well as inside many of the station elevators,” the report said, adding that “other areas of public urination include the top side of subway station entrances such as Pershing Square, where loitering is common.”

But the agency pointed to the complexities of opening new restrooms with a cautionary tale of what happened when The W Hotel, located above the Hollywood and Vine Red Line station, agreed to provide a street-level public toilet as part of their contract with Metro.

According to Metro, the facility “became a magnet for the area’s homeless population which impacted the use by Metro’s customers. While open, the hotel developer was expending an average of $250 per day on paper products and had to replace three sinks, three mirrors and five toilet seats due to damage.” The restroom was labeled a public nuisance and was shuttered less than 4 months after its opening.

Johnson, Metro’s interim operations chief, notes that these kinds of problems are not limited to Metro operations. “It’s something that plagues us in today’s society considering the amount of people who don’t have access to facilities,” she said. “You could be walking around a city street and step around a puddle of urine. Collectively, I think there is an issue that needs to be addressed holistically.”

There’s also the price to consider. According to her department’s report, individual hard-wall toilets cost up to $700,000 to install and require regular stocking, maintenance and cleaning. In December, Robin Blair, the agency’s planning director, estimated that it would cost $70 million annually to maintain restrooms at every station. The agency estimates that the free-standing automatic public toilets would cost about $600,000 for two units, plus considerable custodial costs.

Then there are the public safety issues that come with adding restrooms to the system, thus creating a venue for illegal activity. “If you go anywhere in the world where people have tried this,” Blair said, “all of your problems are in the restrooms—crime, muggings, shooting up—all sorts of human degradation.”

“It’s up to the Board [of Directors] to decide what direction to take,” Johnson said. “For staff, our first and foremost mission is to ensure a safe environment for the riding public.”

No rider, of course, would argue with that goal. But a good number of them, like Renee Briddle, 38, who commutes 2 hours from Long Beach through downtown Los Angeles on the Blue and Red lines, think the status quo stinks.

Briddle was standing next to a small pool of urine the other day in a Civic Center station elevator. “It smells like that all the time,” she said, adding that such conditions are not uncommon, as Metro itself admits. One time, Briddle confided, she herself had an accident during one of her long commutes. “We need bathrooms,” she said, before hurrying on her way.

Posted 2/13/14

Trial by fire for Metro’s new top cop

February 6, 2014

Commander Claus is a SWAT veteran with a dramatically different set of new responsibilities at Metro.

Sheriff’s Commander Michael Claus became the new head of security for Metro’s bus and rail system on January 6. He knew the job would be complicated, but he couldn’t have predicted what would happen next.

A week after he started, on the morning of January 13, a fatal stabbing took place on the Red Line. It was the second killing in the history of the line, and the widely-publicized tragedy forced Claus to throw out his playbook.

“If you can imagine taking a big, giant eraser board that has everything laid out nice and neat, and then just take both hands and move everything around? That’s what it was like,” Claus said.

Luckily, his police instincts kicked in.

“When something like this occurs, you have two issues,” Claus said. “One, you have to solve the problem, find out who did it and hopefully have an arrest—which we did. Second, as an administrator you have to look at what we did, whether we could have prevented it and what we can do now to prevent it in the future. You have to wear two hats.”

The first part comes naturally for Claus, 52, who has more than 33 years of experience as a Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department deputy, SWAT team member and SWAT commander. The administrative part is new territory.

“I left my dream job,” Claus said. “When I was a deputy at SWAT, I always said I wanted to be the first person to work on the unit and then go back and command the unit. And I was the first person to do that. Eight months later I get a phone call and the sheriff asked me to come over here and command this bureau. You don’t tell the sheriff ‘no.’ ”

After decades on patrol, Claus now finds himself doing much of his work from behind a desk.

“This is completely different from anything I’m used to,” he said.

One immediate challenge has been managing public perceptions in the wake of the stabbing, which raised safety concerns among many transit riders. Claus said those fears are understandable, but they’re distorted by this isolated event, in part because of how the media covered it. “It’s like a plane crash,” he said. “After a plane crash they tell you it’s the safest transportation mode in the world. But when there’s a murder, the news doesn’t do that.”

According to Sheriff’s Department statistics, “Part 1” crimes, which include homicide, rape, aggravated assaults and theft crimes, are exceedingly rare on Metro’s system. On the Red Line, for example, there were only 3.8 of those crimes per million riders in 2013. Violent crimes are even rarer, with property offenses like the theft of electronic devices accounting for the majority of that number.

Other than a police station parking lot, Metro is one of the worst places to commit a crime. Perpetrators rarely get away because closed-circuit TV cameras are always watching and camera-equipped passengers serve as witnesses, Claus said. The suspect arrested and charged with the Red Line stabbing was identified using footage from train and station cameras.

“If Metro’s system were a city, it would be the safest city in the country,” said Duane Martin, who manages the agency’s work with the Sheriff’s Department. “People tend to focus on occurrences that are out of the ordinary. When something like this happens on Metro, it stands out.”

Still, even one crime is too many for the people charged with protecting the riding public. Claus is already brainstorming improvements. One idea he’s considering is assigning teams of deputies to the same couple of stations or bus stops every day to create a transit version of community policing, enabling the deputies to get familiar with regular patrons—and potential troublemakers. Currently, deputies are generally assigned to regions that they are familiar with and moved around as needs dictate. Claus wants to focus them on smaller beats to give them a proprietary interest in keeping each area safe.

Both Claus and Metro’s Martin are seeking to improve fare enforcement, a major priority for the agency. Currently, deputies are responsible for making sure that people pay their fares and for issuing citations to violators. But Claus believes that sworn deputies’ skills are better used elsewhere.

“From what I’ve seen so far, I think it’s a waste of a resource for a deputy sheriff to check TAP cards,” Claus said. “Deputy sheriffs should be performing law enforcement functions, not revenue functions.” He added that it’s tough to recruit good people because trained police don’t want to spend their days checking cards.

Claus envisions using Metro employees and security assistants to check fares instead, while deputies patrol for safety—a quick call away if a conflict arises. Martin agrees. “When they are on a train and they have both hands checking tickets, they aren’t looking for quality of life issues,” Martin said. With each sworn deputy costing the agency about $210,000 per year and civilian employees costing about a quarter of that amount, “you want to get the best bang for your buck.”

Claus also wants to improve how his team communicates with the public. “We are going to start educating people about how not to be victims,” he said. Part of that involves common sense steps like securing purses and electronic devices. However, in the case of a verbal or physical confrontation, he said, the best course of action is to be a good witness and stay out of the way. “It’s hard for me to say ‘don’t get involved’ because I’m one of those guys that would get involved,” Claus said. But, as a law enforcement officer, he pointed out, “I also carry a gun.”

Suspicious activity, of course, should be reported by dialing 911 or calling the Sheriff’s Department. But there’s a catch. That only works on buses and above-ground light rail; there is currently no cellular or wireless internet service on the subway. There, passengers should look for emergency phones at either end of each rail car and in the stations, or try to find a Sheriff’s deputy or a Metro employee. The agency is in the process of installing wireless service underground, but the effort will not be completed for about a year. “All we have is radio down there,” Martin said. “Having telephone service will be a godsend for us.”

The Sheriff’s Department acts as an independent contractor with Metro, which is paying the department about $83 million for the current fiscal year. The contract expires in June, and Martin expects that the next contract, which must be put through a competitive bidding process, will include new performance standards and different fare enforcement requirements. The current contract started in July, 2009, before TAP cards and gate latching were implemented. Back then, fare enforcement was done mainly by checking individual paper tickets.

Commander Claus hasn’t been on the job long, but he’s adapting quickly to his new position, which also involves delicate political situations he hasn’t faced before.

Because Metro’s territory cuts across many political boundaries, moving resources around can be touchy. “One of the lines may go through one county Supervisor’s district and one goes through another. They might ask ‘why are you taking resources from my district?’”

On top of that, there’s inherent friction between law enforcement’s duty to investigate crimes and Metro’s mission to reliably transport millions of people from place to place on time. Stopping rail lines for lengthy investigations can be a complex undertaking. “You have to find that happy medium,” Claus said.

It all adds up to a brave new world for a man who decided to become a police officer at age 5 while watching cop shows on television. Like any good administrator, his first task will be to take stock of what he already has.

“I love a challenge,” Claus said. “It’s like taking over a factory that makes cars. First you are going to learn how to make the car, and then you’re going to see if you can do anything better.”

Posted 2/6/14

Record numbers riding easy on Expo

January 29, 2014

The first phase of the Expo Line is getting up to speed—six years ahead of schedule.

Metro had projected the line would be carrying 27,000 riders a day by 2020. It has been surpassing that mark since last fall. In December, an average of 27,360 rode it every weekday.

And, in a win-win for passengers and the transit agency, the line’s success hasn’t translated to overcrowded train cars, at least so far.

Tiffany Laurence, 24, uses Expo to commute from downtown Los Angeles to Culver City. She said that seats are plentiful, even during the morning and evening rush.

“Those are the only times I have someone sitting next to me,” Laurence said. “Normally, I have a whole row to myself—it’s so luxurious.”

Bruce Shelburne, Metro’s rail operations chief, is also glad for the extra room. He said the line will need the seating capacity when the second phase to Santa Monica opens in 2015. Shelburne expects that to draw flocks of commuters and tourists, even on the weekends. “We’re not breathing hard and we’re at 27,000,” he said. “If we were at 40,000 I’d be awfully nervous.”

For now, the extra room offers easygoing rides to people like Jerry Davis, a Houston, Texas, city councilmember who was in town on business on a recent Wednesday.

“The only lines we’ve seen have been the traffic lines, so it makes us want to come to the rail,” Davis said. “It’s a nice, sunny day—we’re putting less emissions into the air and saving the environment.”

Samantha Bricker, Chief Operating Officer for the Exposition Rail Authority, said much of the ridership comes from the numerous entertainment venues and institutions that are along the way, like Staples Center and the University of Southern California. She also said the line draws a lot of people from the Westside. A 600-space park-and-ride lot at the Culver City station—the furthest west spot on the Expo Line so far—regularly fills to capacity in the morning.

Aside from getting people from Point A to Point B, Expo also seems to be changing how they live. Sandip Chakrabarti, a Ph.D. candidate in urban planning at USC, has been studying how the Expo Line has affected the way people who live in the area get around. “There is evidence that it has altered travel behavior quite a bit,” he said. “People near Expo stations have been driving a lot less.” On a personal note, he said that when the line starting running it enabled him to move from an area near the school to Culver City, which he prefers.

For commuters like Peyton McElyea, who takes the rail to his real estate job in downtown Los Angeles, a major part of driving less is being able to use travel time more productively.

“You can read the Wall Street Journal, the morning paper, you can respond to email,” said McElyea. “You know you have that 30-minute block where you can get something done. It’s better than being there with your hands on the wheel.”

Metro’s Shelburne said McElyea’s perspective is not uncommon; rail transit is generally becoming more popular across the board.

“The train’s sexy, that’s the bottom line,” Shelburne said. And the unpredictable traffic on the frequently-gridlocked 10 Freeway doesn’t hurt that appeal. “The train is dependable. It’s going to be that way every day.”

Posted 1/21/14

Orange Line’s “dismal” fare findings

January 16, 2014

The Orange Line, shown at opening of the busway's extension, is popular but many aren't paying to ride.

Up to 22% percent of Orange Line passengers were deliberate fare evaders and as many as 9% “misused” their TAP cards, according to recent audits assessing the extent of fare-beating on the popular San Fernando Valley dedicated busway.

The findings, presented Wednesday to a Metro committee, are “rather dismal,” acknowledged Duane Martin, the agency’s deputy executive officer for project management.

“We understand there’s no glossing over the significant fare evasion,” Martin said, although he added that the recent redeployment of sheriff’s deputies to check fares along the line has improved the situation.

The Orange Line carries about 30,000 riders a day, and unlike the rest of Metro’s fleet, does not have fare boxes on its buses. Instead, it relies on patrons at un-gated stations to tap their fare cards at machines known as “stand alone validators.”

Many, it appears, have been taking advantage of the system to hitch a free ride.

Two audits—conducted December 3 and December 17—surveyed all patrons as they got off the bus at various Orange Line stations. The first audit, at the North Hollywood, Van Nuys and Sherman Way stations, found 22% fare evasion (traveling without a TAP card or using a card with no value on it) and 9% TAP card misuse (having a valid TAP card but, perhaps inadvertently, failing to properly tap it before entering the bus.) The second audit, at the North Hollywood, Reseda and Canoga stations, found 16% fare evasion and 8% TAP card misuse.

The audits were prompted by a November, 2013, motion by Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, a member of Metro’s Board of Directors and a longtime proponent of reforms to help eliminate free riders on the Los Angeles transit system. In a major milestone, gates on the L.A. subway, which for years had operated on the honor system, were finally latched last year. But locking down Metro’s light rail system and the Orange Line, which operates in a similar fashion, is still a challenge.

On Wednesday, Yaroslavsky and another director, Los Angeles City Councilman Paul Krekorian, responded to the Orange Line audit findings with another motion, this one directing Metro staff to explore installing gates at the busway’s stations. They also said that signs explaining that tapping is mandatory (and listing fines for failing to do so) should be placed on or beside the ticket validating machines at the stations.

Moreover, they asked for status reports on gate installation for projects currently being constructed or designed, including phase two of the Expo Line, the Foothill extension of the Gold Line, and the Crenshaw Line.

“Unless we take this issue head-on, and begin to design stations with gates…fare evasion will continue to skyrocket and become a perpetual problem with no end in sight,” the motion said.

“Saturating” the Orange Line with sheriff’s deputies checking fare cards has already started having an impact, including in the period between the first and second audit, Metro deputy executive officer Martin said.

“The deputies are out there so people started tapping again,” he said.

Before Martin reports back to Metro’s board members on the issue in March, he plans to conduct another Orange Line audit, probably next month.

Wiping out all fare evasion is unrealistic, he said, but there is lots of room for improvement. “I would love to be able to operate the system with plus or minus 2% or 3% fare evasion,” Martin said. “That’s the goal.”

Posted 1/16/14

This parking lot’s no paradise

December 6, 2013

On a chilly weekday morning, after squeezing his truck into the last available spot in the main lot at the Universal City/Studio City subway station, Mario Beltran summed up the parking situation in two words: “It’s terrible.”

“If you’re not here by 8 o’clock, you’re out of luck,” said Beltran, 36, as he hurried to catch a train to downtown L.A.

Beltran was lucky that day. According to some of his fellow commuters, lots are often filled up by 7:30 a.m. or even earlier at both of the Valley’s Red Line stations, in Universal City and in North Hollywood.

Some, like 25-year-old Joanna Sintek, who commutes from Burbank to the Natural History Museum in Exposition Park, have had to learn that the hard way.

“I would show up and get grumpy and have nowhere to park,” Sintek said. “I’d just drive instead.”

Since then, Sintek has discovered an L.A. County-owned overflow lot on Ventura Boulevard, but she said it’s a long haul from that lot to the station entrance, and it comes with an uncomfortable passage through a poorly-lit pedestrian tunnel beneath the 101 Freeway.

Parking can be tough in many parts of the city, but the two San Fernando Valley subway stations get extra pressure because they serve as the main transit gateways to Hollywood and downtown L.A.

Help may be on the way. On December 5, Metro’s Board of Directors unanimously passed a motion by L.A. City Councilman Paul Krekorian, County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky and Mayor Eric Garcetti, instructing the agency to investigate possible fixes, such as additional lots, parking garages or a joint development project to increase parking. The motion also directs staff to report back on bicycle and pedestrian improvements that could be made to the stations and surrounding areas.

There are currently 951 spaces at North Hollywood—300 of which are reserved at a cost of $39 per month. At Universal, there are 661 spaces, 140 of which are reserved. The County-owned satellite lot has 160 more spaces.

Robin Blair, Metro’s director of planning, said the agency already is in the process of installing a lot in North Hollywood that will accommodate 187 more vehicles, but he admitted the effort wouldn’t satisfy the rapidly-growing demand.

“There isn’t enough parking, that’s the bottom line,” Blair said.

Metro owns several parcels adjacent to the stations, but Blair is skeptical about building parking-only structures because of the high value of the land, which is located in popular areas like the NoHo Arts District and Universal City. “The sites are valuable as destinations and you are going to have pressure to do some sort of joint development,” he said. “Once you get in the discussion of parking garages, that’s not an option.”

The North Hollywood station is the northern terminus of the Red Line, and Blair said the “transit-shed” of the station—the geographical area from which it draws passengers—is enormous. It is used by about 33,500 people on an average weekday, bringing in people from North Hollywood, Burbank and much of the west San Fernando Valley via the Orange Line. Commuters from as far north as Palmdale drive to the station.

Because of that ridership and the potential for further growth, Blair hopes the station areas themselves can become destinations where people can eat, shop and hang out. That’s in sync with the motion’s intention to create “transit/mobility hubs” that would bring more riders into Metro’s system—and not necessarily just those who get there by car.

For bike advocates, new infrastructure is crucial because the stations border the Orange Line Bike Path, the Chandler Bikeway and a future section of the L.A. River Bike Path that’s in the pipeline. Those paths approach the stations but the parking lots were not designed for bicycle access, said Eric Bruins, director of policy and planning for the L.A. County Bicycle Coalition. He added that the stations bookend a stretch of Lankershim Boulevard where the group is pushing for bike lanes. “If you connect these two hubs with lanes, that neighborhood will really take off,” he said.

The move to create better access to the subway stations is one of three recent proposals that aim to improve the San Fernando Valley’s public transportation experience.

After residents around Pierce College complained that Orange Line patrons were urinating on their walkways and alleys because of a lack of bathrooms, Yaroslavsky, Krekorian and Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich moved to have the agency install bathrooms or come up with another solution. Their motion, adopted by Metro’s Board of Directors last week, also calls for the agency to look into adding bathrooms throughout its rail and bus rapid transit system. Blair said that could be a tall order, however; because of security and maintenance needs, having bathrooms at all stations could cost an estimated $70 million or more a year.

Finally, a motion by Yaroslavsky and Krekorian, adopted by the full board, seeks to curb freeloaders on the Orange Line, where fare evasion enforcement is falling short of the agency’s goal, with officers conducting checks only one-third as often as they should. Potential solutions could include increased enforcement, adding gates to stations, installing additional TAP card readers or improving signage.

For Carlos Mora, a commuter who has lived in transit-friendly cities like London and New York, such fixes are overdue steps toward improving what he calls “the crappiest infrastructure for public transportation ever.”

“It’s getting better,” Mora added, as he headed towards the parking space that he’d waited two months to reserve. “But if it was more these hubs where people could work and live and shop and entertain? That would be awesome.”

Posted 12/6/13

Metro locks in more revenue

October 17, 2013

Do the math. Taking L.A.’s subway system off the honor system should mean a bump for Metro’s bottom line—and that’s exactly what happened in the first month since gate-latching was completed.

According to Metro’s data for September—the first full month available—revenues have increased by 40% when compared to May, the last month before the lengthy gate latching process started. If that increase holds steady, it would mean an extra $6 million in collected fares each year, said David Sutton, Metro’s deputy executive officer in charge of the project.

“An increase in revenue like this can be put back into the system,” Sutton said. “We can increase our hours of operation, add train cars, we can buy more buses—there is a whole myriad of things we can do with that money.”

Meanwhile, weeding out freeloaders means that ridership on the subway lines has decreased, even as the number of paying customers using TAP cards to gain access to the Red and Purple lines has skyrocketed.

Fare evaders are now unable to freely enter the system and, for the most part, have moved on to other modes of travel, Sutton said, giving paying customers a better ride by improving their security and safety—and by opening up a little more elbow room.

Even with the gates latched, some committed scofflaws will always find ways to game the system, Sutton said. About 19,000 people entered the subway without paying in September, using a variety of tricks or blatantly jumping the gates. Metro is in the process of tweaking the new system to make fare evasion more difficult, and the Sheriff’s Department is issuing citations to catch those who squeeze through.

Nonetheless, in most places the system is working well. During one morning rush hour this week, transit patrons streamed through the gates at the North Hollywood station, tapping in succession as they rushed to catch the next train. At ticket vending machines, fare purchases were made swiftly, with no long lines forming.

A few cyclists were slow getting through, lifting their bikes over the top of turnstiles or, like one young woman, tapping a fare card before pushing through an emergency gate. Sutton said cyclists can currently use the elevator to access the system, but few avail themselves of the option. Metro is planning to add a new gate, similar to the gates for disabled patrons, that will offer cyclists an easier path.

And a few fare-beaters were still trying to get a free ride. One teenager hopped over the gate, singing loudly to the music on his headphones.

But, glitches aside, gate latching has already proved transformative for the transit agency. Metro currently is working to bring some latched gates to its expanding light rail system. While not all stations can be latched due to logistical barriers, Sutton said he believes fare collection will continue to improve as Metro latches some stations along the Gold, Blue and Green lines, an effort scheduled for completion by February, 2014.

More than a million TAP cards are currently active in the system, about twice as many as when ticket vending machines were made TAP-only two years ago.

“If you look at the numbers and you look at the behavior, people are tapping,” he said. “I don’t think we’ve ever had gates; it’s a big behavioral change.”

With the assistance of help phones near entry points, Metro has been able to accomplish that change without having staff present at every station.

“It’s been incredibly smooth—we were expecting a lot more customer pushback,” Sutton said. “The biggest thing I remember is people that would give us a thumbs-up and say ‘it’s about time.’ People that pay want and expect everyone else to pay.”

Posted 10/17/13

Gate latching hits a roadblock

September 26, 2013

Elevated light rail stations, like in Culver City, are among the next targets for latching. Photo/L.A. Times

L.A.’s subway system has locked its gates and finally moved past an honor system that’s been in place for more than two decades. But it’s a different story at dozens of Metro light rail stations, which usually have stand-alone fare-card readers but no barriers to entry.

David Sutton, Metro’s deputy executive officer in charge of the gate-latching project, said that won’t change any time soon. Last week, in response to a July motion from several members of the Board of Directors, Sutton and his team released a report on the feasibility of installing lockable turnstiles on Phase 1 of Expo Line and at future stations throughout the expanding rail system.

“We’re not going to be able to lock them all,” Sutton said. “Some of the stations just don’t lend themselves to gates because of the space available and the cost.”

The primary reason is safety, said Rick Meade, who manages station construction for the agency. The National Fire Protection Association requires safe evacuation of platforms within 4 minutes in case of an emergency, as well as clearance to a “safe distance” within 6 minutes.

“As soon as you put gates on there, your exiting calculations are going to change because you have an obstruction that slows everything else down,” Meade said. Underground and aerial stations have space to accommodate enough gates for a swift exit, he said, but street-level stations usually do not. For those, increasing the size of platforms is often the only solution, a costly proposition that can encroach on traffic lanes or other property.

Some stations on the light rail system are already equipped with turnstiles, and their latching is slated for completion by February, Sutton said. On the Gold Line, the 5 out of 21 stations with turnstiles were latched earlier this month. Next up is the Blue Line, where 6 of 21 stations are scheduled to be latched in December, followed by all 14 stations of the elevated Green Line.

Along all Metro’s light rail routes, there currently are 41 stations where customers can enter without a barrier requiring payment, including the entire first phase of Expo Line. Sutton and his team examined the possibility of installing barriers at all non-gated light rail stations and have identified 13 for further analysis.

For Expo’s first phase, Metro estimates it would cost $3.1 million to add gates to three elevated stations, an investment the agency says could be recouped within 7 years because of increased fare collection. At the street-level stations, where there’s no room for gates, Metro is planning to add more stand-alone card validators at a cost of $173,000, plus $141,000 in annual operating expenses. Sutton said the non-gated card readers have been effective elsewhere in the system in reminding riders who want to comply with the rules to tap their fare cards.

“With gates and these kinds of things, it keeps honest people honest,” Sutton said.

Sutton said he plans to return to Metro’s Board of Directors in January with a full engineering analysis of what would be needed to install gates and additional card validators on Expo’s first phase, which goes from downtown to Culver City.

A similar gating scenario is being faced by Expo’s second phase, which will end in Santa Monica and is now under construction. At least two of the seven stations in that phase could not have locked gates, while four others are able to accommodate barriers and one other is being reviewed. For future rail projects that have yet to be designed or constructed, lockable gates will be required, Sutton said.

Meanwhile, on the Red and Purple lines, where gates have already been latched, preliminary data on fare collection for August is encouraging, showing a 22% increase in ticket machine sales over the same month last year—worth more than $614,000. Sutton said many free riders have left the system, opening more seats for paying customers.

The latched stations have also been a help to law enforcement, said Lieutenant Sergio Aloma, a transit services officer with the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department, which is tasked with policing the system.

“Any time you can latch stations, it is better from a fare enforcement standpoint,” Aloma said. “I just wish we could latch them all.”

Aloma said latching even some gates allows officers to be deployed in larger numbers to non-gated locations. The increased visibility of law enforcement, he said, works as a deterrent to would-be fare evaders.

Aloma also said that, even at stations where gates are locked, dedicated scofflaws will find ways to beat the system by, for example, sneaking through access points for disabled people or jumping turnstiles. On the other hand, some riders may make honest mistakes such as forgetting to tap their fare cards when transferring lines as they try to figure out the new system.

“In some cases deputies have to use discretion and determine whether we need to take a customer-relations viewpoint or an enforcement viewpoint,” Aloma said. “This is still new and we want to educate folks on how to use the system.”

Posted 9/26/13

Look what’s next on Wilshire

September 5, 2013

Purple-blooming jacaranda trees, shown in rendering above, will be spared when new Wilshire bus lane is built.

As the Wilshire segment of the massive 405 Project winds down, with the completion of sweeping new flyover ramps in the months ahead, another big project is about to hit the boulevard.

The Wilshire Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) project, which is creating a dedicated bus lane running from MacArthur Park to the border of Santa Monica, is set to begin work in March, 2014, on a segment of Wilshire Boulevard near the V.A. Hospital in West Los Angeles.

Construction on the Wilshire segment of the 405 Project is expected to wrap up by January, 2014. With the exception of some landscaping work, the freeway project is not anticipated to overlap with the bus lane construction.

In the V.A.-area section of the bus project, Wilshire is being widened from Bonsall Avenue to Federal/San Vicente to incorporate a new eastbound lane that buses will be able to use exclusively during peak morning and afternoon rush hour periods. In the off-hours, the new lane will be available to all vehicles.

Initially, there were concerns that more than 30 jacaranda trees that line the median on Wilshire between Federal and Bonsall would need to be removed as part of the project.

Now, however, plans call for the trees to be boxed up during construction and replanted when the widening project has been completed. Trees deemed not healthy enough to survive transplanting will be replaced.

“We’re going to improve the situation,” said Lance Grindle of the county Department of Public Works, which is designing the project and overseeing work on the .8 mile stretch. New street lighting is being installed, along with a new, more reliable irrigation system.

“There are quite a few nice healthy trees there. There are also quite a few trees that are in distress because they didn’t get enough water,” Grindle said.

In addition to replacing the jacarandas in the median, more than 35 Brisbane box trees will be planted along the north side of the boulevard with other landscaping.

“It actually creates a nice little walking area,” Grindle said.

The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors this week authorized Public Works to move ahead with the V.A. segment of the project.

Martha Butler, director of regional transit planning for Metro, the lead agency for the project as a whole, said the new lane is essential to speeding up bus travel times along Wilshire.

“It’s the most important corridor in the county, our No. 1 in terms of ridership,” Butler said. She said the bus station at Bonsall, serving the V.A., is particularly heavily used, with 700 boardings a day.

“It really provides a critical service to veterans,” she said.

Butler noted that the new bus lane is an addition to the existing lanes on Wilshire and will not usurp any current travel space. Construction will take place in phases, beginning with the north side of Wilshire, and two lanes will remain open in each direction throughout the project. In addition to the new bus lane, there will be longer left-turn pockets on westbound Wilshire at San Vicente and on eastbound Wilshire at Sepulveda.

An initial segment of the BRT project—which in its entirety will span 12.5 miles, including 7.7 miles for buses only during peak hours—opened in June from MacArthur Park to Western Avenue. Construction on the segment running from Western to San Vicente is expected to begin this month. (The dedicated bus route is not continuous, as this map shows. Areas excluded from the project include the entire stretch of Wilshire through Beverly Hills and a one-mile stretch in Westwood.)

When the whole project is completed in November, 2014, average travel times along the corridor are expected to improve by 24% and spark a bus ridership increase of 15% to 20%.

Posted 9/5/13

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink