Community Law Enforcement

Board orders audit of sheriff’s budget

January 23, 2013

Sheriff patrols have been reduced throughout the county's unincorporated areas. Photo/Navymailman via Flickr

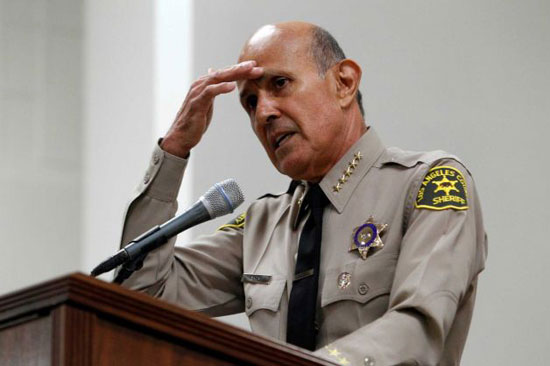

After a testy public confrontation with Los Angeles County Sheriff Lee Baca over patrol cutbacks, the Board of Supervisors unanimously called for a “forensic audit” of his department’s $2.8 billion budget.

The Tuesday action came after several supervisors accused the sheriff of potentially jeopardizing public safety by reducing the number of patrol cars in the county’s unincorporated areas to save money on rising overtime costs.

Baca insisted that, with crime rates down substantially, there was little danger that fewer patrol cars would lead to higher public risks. He said he had no choice after being hit with multimillion dollar budget cuts for three consecutive years and unacceptable overtime costs in recent weeks.

“We have the largest county in the United States, and the safest county in the United States,” Baca said, adding: “I just believe we need to account to [the public] as to what we’re doing and what are the true facts regarding their safety.”

Although the Board of Supervisors sets the department’s budget, the sheriff has wide discretion over how it’s actually spent.

During Tuesday’s Board hearing, Baca faced the stiffest criticism from Supervisor Gloria Molina, whose district includes the unincorporated community of East Los Angeles, among others.

“I’d like to cut your budget in other places and I’m going to try and find a way,” warned Molina, who joined with colleague Don Knabe in introducing the motion for an independent audit of the department’s budget.

Both Molina and Knabe suggested that Baca was undermining an “equity policy” ensuring that unincorporated areas get the same level of services as cities that contract with the department. Instead, Molina said, costs are being reduced in unincorporated areas to subsidize other department functions and responsibilities.

“You are stealing,” she told the sheriff, who responded: “Stealing is over the top, supervisor.”

“I want you to let me finish,” Molina interrupted.

“Not when you say something that is so outrageous that it’s not worth the dignity of your office,” the sheriff said.

Later, Molina apologized for the “stealing” characterization, and Baca thanked her for being a “stellar supporter” of the department. The sheriff also assured the board that he was already taking measures to ensure that patrol levels would not be reduced for long, including in the unincorporated area of Topanga Canyon in Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s district. The vast majority of his district is patrolled by the Los Angeles Police Department.

No date was set for completion of the independent audit, which will be arranged through the county’s Auditor-Controller’s Office.

Posted 1/23/13

Playing through the pain

November 20, 2012

Rival gang members stand face-to-face, struggling to transcend their natural hostility towards one another. But it’s not a real-life showdown. They’re portraying lovers, lead actors in a play they helped write. In fact, it’s just another day in the life for The Unusual Suspects, a nonprofit group that teaches at Camp David Gonzales, a Los Angeles County juvenile detention center.

Sally Fairman, the group’s executive director, says theater arts are an ideal form of expression for the boys, who are incarcerated at the camps for serious crimes. In preparing to confront an audience, students are compelled to confront their own demons.

“Because they are going to be in front of people with their story, they have a big investment,” Fairman says. “They really have to come together if they want to succeed. Every player is important to the show and each of them feels that sense of importance to themselves and to their fellows.”

The educational program consists of two 10-week sessions, each culminating in a live performance. The first session focuses on playwriting. When it’s over, professional actors perform the play under the direction of the young writers, who offer advice on how to portray their characters. The second session centers on performance, using games and improv to teach acting skills. At the end of that session, the students themselves perform the play. The staff and teaching artists are theater pros, and they teach in a hands-on style, about one teacher to every 3 kids.

It’s not always smooth sailing. Many of the kids carry the baggage of physical and sexual abuse, drug and alcohol issues and abandonment problems from absentee parents. A good number of them have gang affiliations, like the two rivals who were playing opposite each other as lovers in true Shakespearean tradition, with one taking the role of a woman. These obstacles must be overcome for a successful play.

Getting beyond such issues is the underlying goal of the program, according to Michal Sela-Amit, a board member of the group who chairs the Families and Children Concentration at USC’s School of Social Work. The camp workshops are intended to function like group therapy sessions, although that’s not how it feels to participants. They’re too busy acting and writing.

“They’re not going to come to therapy that quickly and they’re not going to talk about those things so willingly,” Sela-Amit says of the workshops. “Drama works on so many levels—with the individual, the group, the audience—you’re having fun with a group of people.”

Sela-Amit says the program is intended to maximize a person’s full brain power. She says that traumatic experiences, such as those experienced by the young adults in the camps, settle into the brain’s more creative right side, where they inhibit learning and growth and create worries and anxieties. The exercises of writing and acting, she says, essentially push these traumas to the brain’s more logical left side, where they can be processed. Once that happens, new neural connections can form, enhancing an individual’s ability to interact with society in a more positive way.

Mike Varela, director of Camp Gonzales for the county’s Probation Department, says he can see the results as tough guys at his camp break out of the hard shells they’ve built up over the years.

“You have these hard guys with these façades, and suddenly they are laughing and having the time of their life,” he says.

This Saturday, November 10 at 1 p.m., professional actors will perform the students’ latest composition—Money, Power, & Regret—for a public audience at Camp Gonzales. (For security reasons, advance reservations are required for those who want to attend. While the official deadline for reservations has just passed, staff from the Unusual Suspects said they will try to accommodate late requests. For more information, email [email protected].)

The Unusual Suspects was founded in 1993 by actress Laura Leigh Hughes in response to the Los Angeles riots of the previous year. The group first came to Camp Gonzales in 2004. Over the years, the group has taught thousands of youths, now averaging about 300 per year across the region.

The organization reaches beyond detention facilities, too, to kids ages 9 to 21, who live in high-crime, impoverished and underserved areas. Fairman says the program is always evolving, and they’ve recently started engaging multi-generational groups in south L.A. and Pacoima, with positive results. Older members of the communities are getting involved after seeing their own lives reflected in the performances, she says.

Fairman wants to keep adding The Unusual Suspects’ brand of therapeutic theater to the existing mix of tools and organizations in local communities. So far, she says, communities have embraced the program and offered their own suggestions, such as incorporating visual arts, dance and cultural traditions.

“I would like to see us be a model, expand nationally,” says Executive Director Fairman, “and help more communities place arts at the center of their strategies for transformation.”

Actors Marcus Woodswelch and Hilary Ward portray characters in "The Lost Son," a play written by Camp Gonzales students in 2011.

Posted 11/8/12

The big inmate shift: one year later

October 12, 2012

Appointed last October, Probation Chief Jerry Powers promptly became responsible for realignment's rollout.

Don’t expect a lot of folks in Los Angeles government to be toasting Sacramento in celebration of this month’s one-year anniversary of the most dramatic remake ever of California’s criminal justice system. Called “realignment,” it triggered a massive overnight transfer from the state to its counties of responsibility for supervising certain ex-prisoners and jailing a new, more serious class of offender.

The changes were pushed by the governor and legislature despite strong resistance from local authorities, who argued that the plan was being rushed to relieve the state of its prison crowding and budget problems at the expense of public safety and the dwindling resources of local governments.

Now, data collected by Los Angeles County suggests that the impact here is even more challenging than anyone envisioned, prompting a scramble for new solutions and dollars.

County officials say, for example, that they received more “high risk” former state inmates to supervise than they’d initially predicted, and many arrived with mental illnesses that were far more serious than expected. Those individuals have been placed in costly lock-down psychiatric facilities, leap-frogging other patients who’ve been bumped to waiting lists and, as a result, are consuming precious beds in public hospitals.

Meanwhile, more than 30% of the 11,000 former state inmates whose supervision has been transferred to the county’s Probation Department were rearrested during the past year for allegedly committing crimes ranging from vehicle code violations to serious felonies, including 16 murders, 23 attempted murders and 205 robberies. County officials emphasize, however, that these same alleged offenses could just as easily have occurred had state parole officers remained responsible for post-release supervision.

And it doesn’t end there. County probation Chief Jerry Powers says another provision of the realignment law, AB 109, carries the potential of even more problems, placing new strains on the county’s already bursting jail system and raising more questions about risks to the public.

Under AB 109, the county is now responsible for jailing criminals convicted of non-serious, non-violent, non-sexual crimes—offenders, who, in the past, would have been sentenced to state prison and placed on parole after their release. But under the realignment law, there’s no requirement—or funding source—for them to have any supervision, or “tail,” at all after their release from county jail.

“Frankly,” Powers told the Board of Supervisors this week, “that scares me more than this population that is coming from the state prison system [for county supervision.]”

The news, however, is not all grim.

Reaver Bingham, the point man for realignment in the county’s Probation Department, says his agency has, among other things, begun to beef up supervision ratios because of the unexpected number of ex-state inmates who are considered to be higher risks to commit new crimes. “If they mess up,” he says, “we’re right there to address the violation.”

He also said that 90% of the former state prisoners who’ve been ordered since last October to report to the county had done so, allowing authorities to create customized supervision and treatment plans for them. Of those who failed to show, Bingham says, warrants were issued and most of the missing individuals were contacted or picked up within 30 days. As of this week, he says, there are 917 active warrants, not counting the 529 warrants issued for individuals who’ve now been deported. Bingham acknowledged that some of the county’s new charges have been arrested for new crimes—some of them serious—but he says most are property- and drug-related offenses. More than 600 cases, for example, were for methamphetamine possession, while nearly 400 involved arrests for burglary, according to Sheriff’s Department records.

Bingham says the recidivism among the group is not surprising. Although these ex-inmates were transferred from the state after completing sentences for non-violent, non-serious, non-sexual offenses, they often have earlier, more egregious convictions. “I think it’s safe to say that over 50% have serious and violent crimes in their past,” says Bingham, a 30-year veteran of the probation department.

Like his boss, Powers, Bingham says he’s also concerned about the lack of post-release supervision for inmates who, for the first time, will be serving sentences in county jail rather than in state institutions. So far, the average jail stay for these individuals is 12 months, excluding time already spent in custody and automatic reductions in sentences.

“When they’re out, they’re done,” Bingham says. In the past, when this same class of inmate was released from state prison, they’d receive years of parole supervision, giving California authorities leverage to try to avert bad behavior and reduce recidivism. “Without supervision, we have no opportunity to determine whether these people have benefited from programs they’ve received during incarceration with us,” Bingham says. “We have no idea whether the rehabilitation took to them.”

Law enforcement authorities throughout California have been pushing for legislation that, at a minimum, would attach a “search and seizure” requirement to the release of inmates from county facilities, just as the state has been doing for the same class of prisoner. This would give authorities the right to search a person and his property. Any violations could lead to the filing of new charges.

“At least that way, the system is still in their life,” says Mark Delgado, executive director of the Countywide Criminal Justice Coordinating Committee, which has played a key role in the realignment process here.

From the start, one of the most difficult populations to address in realignment has been those inmates with mental health needs. Initially—until the intervention of the governor’s office—county officials couldn’t even get complete medical histories of these individuals from the state to create treatment programs.

Dr. Marvin Southard, director of the county’s Department of Mental Health, says some of these ex-inmates have “garden variety mental illnesses,” for which about half are engaged in treatment. “The challenge has been that there’s a second minority group with very severe mental illnesses.”

These people, Southard says, have been immediately placed in secure, privately-owned psychiatric facilities with which the county has contracts. “Any one of those cases could have been problematic for individual and public safety,” Southard says.

But, according to Southard, there’s been a price to pay—both in dollars and in the operation of the mental health system. These AB 109 clients, he says, “have jumped the line,” creating a backlog among patients in serious need of those same beds. “This has put more pressure on the psych wards at the county hospitals. It backs up the system.”

Still, Southard, Delgado, Bingham and others say there has been a bright spot in all of this: realignment has forced an unprecedented level of cooperation among agencies throughout the county.

Just last week, for example, the Department of Mental Health, the Sheriff’s Department and the Department of Public Health teamed up to begin providing the new AB109 inmates in county jail with a promising anti-addiction drug called Vivitrol.

“We’re working together more synergistically now than we ever have,” says Bingham, who credits his staff with helping make interagency strides.

“Whether you agree with realignment or not,” adds Delgado, “everyone has pulled together, committed resources and been fully invested in doing whatever they can to make this thing work.”

Posted 10/12/12

Sheriff agrees to broad jail reforms

October 3, 2012

Breaking a nearly week-long silence, Sheriff Lee Baca says he applauds the commission's efforts. Photo/AP

Chastened and conciliatory, Los Angeles County Sheriff Lee Baca said Wednesday that he fully agrees with—and will begin implementing—dozens of recommendations from a blue-ribbon panel that accused him and his top command of failures in leadership that fostered a culture of brutality among jail deputies.

“I couldn’t have written them better myself,” Baca said of the more than 60 recommendations issued last week by the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence, which concluded a year-long investigation with a blistering report on management breakdowns inside the nation’s largest jail system.

But, in response to a question during a packed news conference, the elected sheriff brushed aside talk of a possible resignation. “I’m not a person who thinks about quitting on anything,” he said.

Baca convened the massive media gathering in the chapel of the Men’s Central Jail, an aging facility on the edge of downtown Los Angeles, where the vast majority of brutality allegations against deputies have been leveled over the years by inmates and civilian monitors, including the ACLU. As Baca spoke from the pulpit under a large cross, more than 20 members of his jail command staff sat solemnly behind him, some on risers. In the pews—behind a bank of TV cameras—were rows of inmates, dressed in L.A. County’s jailhouse blues.

It was an usually theatrical setting for the sheriff’s first response to the 194-page report by the jail commission, which was appointed by the Board of Supervisors and included former judges, a police chief and a longtime South Los Angeles pastor. And he went to great lengths not to criticize any aspect of the commission’s effort, which he said he supported from the outset. “I’m paid to take criticism,” said the sheriff, dressed in uniform. “Even when it’s unfair.”

In fact, as he has in the past, Baca was quick to accept blame for use of force issues that had been intensifying for several years. Those problems became especially acute under the leadership of Undersheriff Paul Tanaka, according to the commission. The panelists concluded that Tanaka had “exacerbated” the problems by, among other things, publicly belittling internal affairs investigators and unilaterally killing a plan to break-up deputy cliques by rotating them into new jail assignments.

“They needed me to set a higher standard for performance,” Baca said of Tanaka and other key members of his command staff, whom the sheriff said had failed to alert him to the brewing problems inside the crowded county lockup.

The commission was highly critical of Baca for not holding Tanaka and others accountable for their conduct, saying his failure to act has sent a troublesome message to the rank and file. Repeatedly pressed on that point by reporters on Thursday, the sheriff sharpened his tone. “I’m not a person who acts impulsively or in my own self interest when it comes to someone else’s career. We will either have the facts or we won’t have the facts.”

Baca, who said he is reviewing Tanaka’s conduct, added: “I don’t lead with my ego. I lead with my intellect.”

The sheriff said Tanaka, a certified public accountant who was not at Wednesday’s event, would remain with the department, overseeing administrative services and the agency’s budget, a far smaller portfolio than he once held.

Among the commission recommendations (read the panel’s executive summary here), Baca said he supports two that, in concept, would vastly enhance oversight of the jail operation.

One would create an independent Office of Inspector General reporting to the Board of Supervisors. The new agency would essentially consolidate and broaden the review responsibilities of three existing civilian bodies—the Special Counsel, Office of Independent Review and the Office of the Ombudsman. The idea for an inspector general is modeled after a watchdog agency that oversees the Los Angeles Police Department. Exactly how such a body would be created and function for the Sheriff’s Department will likely be a matter of considerable public debate.

The second recommended reform would be the creation of a new assistant sheriff position, staffed by an experienced corrections leader from outside the department. This person would report directly to Baca, who said he supports the idea and already is seeking candidates.

The commission also called for tougher discipline for excessive force and dishonesty, a simplification of the disciplinary system and creation of a new investigations division that would report directly to the sheriff.

Baca said he welcomes these recommendations as a way to make “a stronger and safer jail,” a place where deputies respect the humanity of inmates, who, for their part, can learn life skills and end the cycle of recidivism. “I do have some deputies who have done some terrible things,” he said.

Still, Baca stressed that since last October when the ACLU presented him with numerous accusations of excessive force in the jail, he aggressively instituted a series of measures that have reduced “significant force” in the jails by 53 percent—“a historic low,” he said. He said he also has initiated tough new policies while increasing supervision, video surveillance and training. Baca said he and his management team have “responded massively.” (A video of Baca’s hour-long news conference can be seen here.)

In its report, the jail commission acknowledged the significant improvements Baca had brought to the custody operation after he belatedly became engaged with the issues. But commission member Robert Bonner, a former federal judge and ex-head of the Drug Enforcement Administration, said those measures do not go far enough and that the department needs sweeping cultural and structural changes.

“The modest steps taken by the sheriff are not permanent, institutional reforms,” Bonner said during last week’s commission meeting. “They are Band-Aids—meant to staunch the bleeding.”

Posted 10/3/12

Stopping a danger in the sand

April 4, 2012

Rescuers work feverishly to uncover a teen in Newport Beach who was buried for 30 minutes but survived.

The county’s new beach ordinance may have launched more than its share of wisecracks about allegedly outlaw Frisbees, but lifeguards say that at least one of the less-discussed changes could save lives—and that’s no joke.

The new law, which won final approval from the Board of Supervisors on Tuesday, bans the digging of holes deeper than 18 inches to avert dangers not widely known to beachgoers, said Los Angeles County Lifeguard Section Chief Mickey Gallagher.

“In my 40-year career, people have been badly injured and even killed as a result of sand tunneling,” he said. “This is about a safety hazard. It isn’t about little kids with plastic shovels digging a little hole in the sand.”

Last August, for instance, a teenager was buried alive for more than 30 minutes in Newport Beach. The then-17-year-old boy was building a tunnel when the sand collapsed around him. He survived, several feet below ground, only because he had managed to wiggle his head a little as the sand poured in around him, creating a slight air pocket that kept him alive long enough for emergency crews and bystanders to get to him.

Two months before that, in June 2011, a Northern California teenager on a beach outing with a church group was permanently disabled after being buried for more than 10 minutes when a sand tunnel collapsed on him.

In the same week, according to Los Angeles County lifeguard records, a 10-year-old boy in Manhattan Beach was rescued from a similar situation—only the top of the boy’s head was showing when the lifeguard found him. He’d been lying on his back in a hole, tunneling laterally, and had ignored a prior warning to stop digging because it was dangerous.

Nine months earlier, on Labor Day weekend, a 3-year-old toddler was taken by air ambulance from Zuma Beach to Harbor-UCLA Medical Center after she crawled into a sand hole that had collapsed on her, county lifeguard records show.

And two months before that, on July 25, 2010, an 11-year-old boy burrowing in Manhattan Beach was buried for five minutes as more than a dozen beachgoers, emergency workers and lifeguards tried frantically to extricate him. Lifeguards later said that the only reason they even located him was that his cousin had run, screaming, for help and one of his rescuers had glimpsed a patch of his blue swim trunks as they dug blindly under the sand’s surface. By the time he was pulled free, his lips were blue and he had stopped breathing; he vomited sand after a physician who happened to be at the scene administered mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

“Sand is really unstable, even when it’s hard-packed,” said Gallagher. “Every year, someone will try to dig a deep hole, or tunnel in from a steep berm after a high tide and get into trouble. Some people actually come down to the beach with big shovels, like you use in construction.

“People think they can make a tunnel or a cave, and to the untrained eye, the sand may seem fine because it’s wet. But without support, those tunnels will collapse, and sand is extremely heavy. And once someone is buried, it’s extremely hard to find them. And there’s no oxygen down there.”

The revisions to the beach ordinance make a number of other clarifications to the existing rules for recreation at the beach. Among other things, they make clear for the first time that Frisbees and footballs are allowed on the beach, albeit with certain restrictions. (Basically, you can do it anytime except when it endangers someone or a lifeguard deems it unsafe.)

Inaccurate press reports initially drew criticism of the changes, including the ban on digging, which was derided as meddlesome fun-killing. But Beaches & Harbors Director Santos Kreimann says lifeguards requested the digging restrictions so they could have legal backup in preventing a problem they’ve informally been guarding against for generations.

Beyond dangers to the diggers, Kreimann said, holes in the sand also create a hazard for emergency workers, who are jolted by them when they transport people with neck and back injuries.

“The bottom line is: Have a good time and play in the sand if you want to,” Kreimann said. “But don’t dig more than knee-deep, and if you make a hole, fill it back up.”

All that's left: the hole in Newport Beach where sand swallowed a 17-year-old boy. Photo/Los Angeles Times

Posted 4/3/12

OMG i just got pulled over :(

April 4, 2012

Text messaging is all the rage these days—even grandmas and grandpas are doing it. Unfortunately, texting and driving is as dangerous as getting behind the wheel after a couple of cocktails. If you have a habit of using a hand-held phone while driving, now is a good time to break it—local law enforcement is cracking down on the practice for Distracted Driving Month.

“People are so distracted that they don’t even notice a patrol car has pulled up beside them,” said Sgt. Richard Cohen of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department.

Law enforcement agencies statewide are strictly enforcing California’s distracted driving laws this month. Motorists caught texting or operating hand-held cell phones will be fined a minimum of $159 for the first violation and $279 for subsequent violations.

California is one of nine states that ban texting and other hand-held phone usage while driving (like talking on the speakerphone while the phone is in your hand). According to the federal Department of Transportation, California road fatalities dropped 22% within two years of the initial ban taking effect.

Distracted driving in general includes texting, eating, grooming and other activities that divert a driver’s attention from the road. In 2009, crashes involving distracted driving resulted in 5,474 deaths and 448,000 injuries. Texting while driving was found to make crashes 23 times more likely than driving without distraction. For more statistics and information, visit the transportation department’s distracted driving website or check out the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s summary of the issue.

For everyone’s safety (and to avoid hefty fines), Cohen urges drivers to wait or pull over at a safe location if it’s necessary to use the phone. One quick message behind the wheel could mean loved ones might not actually “c u in 30 min.”

Posted 4/4/12

At probation, the new powers that be

October 26, 2011

Jerry Powers could have predicted as much. The first paragraph of the Los Angeles Daily News story announcing his hiring Tuesday by the Board of Supervisors began with the phrase, “Los Angeles County’s troubled Probation Department has a new chief.”

Jerry Powers could have predicted as much. The first paragraph of the Los Angeles Daily News story announcing his hiring Tuesday by the Board of Supervisors began with the phrase, “Los Angeles County’s troubled Probation Department has a new chief.”

“Every news report, it’s the same thing, ‘troubled, troubled, troubled,” Powers was saying just the other day. “I was joking with the board that my cards will have my name, title and ‘Troubled L.A. County Probation Department.’ ”

Powers, of course, knows that reporters are unlikely to abandon the descriptive shorthand until he gives them a new story line, a daunting challenge for an agency that has, among many other things, come under intense Justice Department scrutiny for failures in its juvenile camps, severe budgeting lapses and considerable churn at the top. Powers’ predecessor is leaving after only 18 months on the job.

“We’ve got some flaws, and some work to do,” Powers acknowledges. “That’s been well documented. But I’m convinced we can fix that. This department can be a leader in the field again.”

Powers, who’ll begin work on December 5 and earn an annual salary of $255,000, is likely to experience some culture shock, not only because of the enormity of the issues confronting the department but because of its sheer bulk.

He’ll arrive here after a well respected career in Stanislaus Countyin the northern Central Valley, where he’s been chief probation officer since 2002. There, the department’s 250 employees oversee 7,000 adults and 900 juveniles. Its budget is $25 million.

Those numbers, however, represent a fraction of what Powers will confront inLos AngelesCounty, where 6,200 staffers supervise more than 50,000 adults and 20,000 juveniles. Its budget is $716 million.

What’s more, no probation department in Californiawill feel a greater impact from the state’s new criminal justice “realignment” law, which transfers to the counties the responsibility of supervising newly-released prison inmates who’d been serving sentences for non-violent, non-serious, non-sexual crimes.

In Los Angeles County, these paroled inmates—many with prior histories of serious and violent crimes—are predicted to number 9,000 by June.

Asked how he’ll make the adjustment from a relatively small operation to such a huge one, Powers says “that’s the No. 1 question.” But he’s convinced “it’s strictly a leadership issue,” whether you’re responsible for 250 employees or 2,500. And that means “being visible, holding people accountable and putting people in the right places to succeed.”

Powers, who is president of California’s association of probation chiefs—and was a reported finalist to become Stanislaus County’s chief executive officer until taking the L.A. job—describes himself as a “collaborative” and “flexible” leader, “who’s pretty sure about what I want and what I don’t want.”

“But at the end of the day,” he says, “I’m ultimately responsible, and we’re [the staff] going to move in the same direction. And if you’re not interested in pulling in the same direction, then we’ll get people who are. The vast majority of people here do not want to work for a ‘troubled’ department. They want to be proud of who they work for and know that what they do is of value to the community.”

Posted 10/26/11

County re-ups with Homeboy

July 13, 2011

Nine months after Los Angeles County stepped in to help keep the doors open at Homeboy Industries, its contract for re-entry services has been extended, preserving a key source of job training for gang-affiliated probationers and parolees.

Nine months after Los Angeles County stepped in to help keep the doors open at Homeboy Industries, its contract for re-entry services has been extended, preserving a key source of job training for gang-affiliated probationers and parolees.

The Board of Supervisors on Tuesday voted to renew the county’s $1.3 million agreement with Homeboy, which originally had been approved as a 9-month pilot project.

The public money will pay for 12 more months of job training, tattoo removal, legal counseling and other services for more than 600 county probationers and parolees between the ages of 14 and 30. It also will continue to fund 20 to 30 revolving job trainee positions at Homeboy businesses, along with an ongoing outside evaluation of the program’s effectiveness.

Although the final evaluation of the joint venture’s first nine months won’t be complete until August, the social scientists conducting it say Homeboy’s success rate appears to be strikingly higher than the national average.

UCLA adjunct professor Jorja Leap said preliminary data shows approximately 80% of the county-funded trainees to be either fully employed or still enrolled in the Homeboy program at the end of the initial 9-month contract, with only about 10% back behind bars. The national rate of re-incarceration among gang members is about seven times higher than that, Leap says.

“This is all very cautionary and short term, and with the contract renewed, we’ll be able to learn even more,” she says. But if the numbers hold up, “it’s absolutely phenomenal.”

Founded in 1992 by the Rev. Greg Boyle, a Jesuit priest, Homeboy Industries is the nation’s largest gang intervention program. Operating under the slogan, “Nothing stops a bullet like a job,” the organization operates a bakery, two cafes, a silk screening and embroidery shop and a janitorial company, among other endeavors.

The organization also is known for its tattoo removal program—a prosaic but potentially life-altering service that annually eliminates a crucial job impediment for thousands of repentant gang members. Boyle has said Homeboy’s job training, educational, legal and mental health services help some 12,000 at-risk youths and young adults every year.

Boyle has noted that Homeboy has served for years as the county’s unofficial—and largely un-reimbursed—“after-care and re-entry program for gang members.” According to Leap’s preliminary numbers, Homeboy’s client base is overwhelmingly, if not entirely, made up of county probationers and parolees who came to Homeboy on their own initiative.

The county also runs various re-entry programs for ex-inmates, but the demand for help far outstrips the supply, says Cal Remington, chief deputy of the county’s Department of Probation. So when a financial shortfall last year forced the organization to lay off hundreds of staffers, Homeboy turned to the county as a natural ally.

“This is really a public safety issue for the county,” says Homeboy’s Chief Operating Officer Veronica Vargas. “You can’t expect someone who has never held a job to walk back into society and know how to get hired.”

Remington calls Homeboy “a good resource,” particularly in light of the state’s desire to shift responsibility to the county for thousands of non-violent parolees, who “still tend to need a lot of resources wrapped around them…Homeboy is legitimate, and has credibility in the community, so I think they could have a real role to play.”

Posted 6/28/11

Hall of Justice to reopen in 2014

July 10, 2011

Los Angeles’ long-slumbering Hall of Justice just moved closer to a 2014 reawakening as a new home for the Sheriff’s Department and members of the District Attorney’s staff.

Los Angeles’ long-slumbering Hall of Justice just moved closer to a 2014 reawakening as a new home for the Sheriff’s Department and members of the District Attorney’s staff.

The storied 1925 building, which played host to some of L.A.’s most famous and infamous figures, from Charles Manson and Sirhan Sirhan to Marilyn Monroe after her death, has been closed since the Northridge earthquake in 1994.

Since then, workers have virtually gutted the space to set the stage for the hall’s revival. On Tuesday, the Board of Supervisors approved a design-build contractor, Clark Construction Group California LP, to finish the job.

The board’s action set the budget for the project at $231,785,000. Long term bonds were issued to fund the project in November. A report submitted to supervisors said the debt service on the bonds would be more than covered by lease savings realized by moving staff into the rehabilitated building. Over 30 years, the net lease savings would be $160,300,000, the report said.

When finished, the building will feature 308,000 square feet of office space and a 1,000-space parking structure.

Clark is set to begin design-build work next month. The report said the company has offered to upgrade the finished building’s environmental ranking from LEED Silver to LEED Gold at no additional cost to the county.

To get a look at the Hall of Justice’s historic interior as it awaits transformation, check out this flashlight tour.

Posted 7/12/11

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink