Top Story: Public Safety

D.A. sees new day for mentally ill

November 20, 2014

District Atty. Jackie Lacey tells the Board of Supervisors that jail diversion is “right within my mission.”

When Jackie Lacey won election as district attorney in 2012, no one expected the county’s chief prosecutor to become a crusader for taking people out of—rather than into—jail.

Yet this month, she was again center stage before the county Board of Supervisors to push for sweeping, if gradual, reforms to provide the mentally ill with alternatives to incarceration.

“Too often, our default position is to lock mentally ill people away because of a perception that there is no alternative,” Lacey said. “Well, there are alternatives — we just need to dedicate resources to expanding the capacity of those alternatives.”

Flanked by leaders of the county’s criminal justice system and social safety net, and with advocates for the mentally ill sitting in the audience, Lacey vowed to present a comprehensive report on diversion programs in early 2015.

She emphasized that initial goals for the Criminal Justice Mental Health Project should be “modest and achievable.” Progress, she said, would take time.

“I want to temper our expectations for a quick fix,” Lacey told the board, pointing out that the county is so large and complex that it’s “a country unto itself.”

Still, there is a sense of urgency to the undertaking, not just for mentally ill inmates whose conditions are worsening behind bars. The U.S. Department of Justice has accused the county of failing in its constitutional duty to adequately serve mentally ill inmates and will likely force the county into a court-supervised federal consent decree.

Although the board is weighing a $1.7-billion proposal to replace Men’s Central Jail with a Consolidated Correctional Treatment Facility, envisioned as “a treatment facility for inmates, construction won’t be completed for years.

The county does have diversion programs already in place for the mentally ill but none has the capacity to serve the vast numbers of people whose schizophrenia, paranoia, bipolar disorder and other conditions may cause them to run afoul of the law. An estimated 15 percent of county’s 20,000 inmates have been diagnosed with a mental illness.

A pilot program was recently created to provide permanent supportive housing for 50 chronically homeless, mentally ill people who’ve been arrested for low-level offenses in the San Fernando Valley. Championed by the office of Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, the Third District Diversion and Alternative Sentencing Program is envisioned as a potential template for diversion programs countywide.

Currently, the Department of Mental Health has only three psychiatric urgent care centers and three crisis residential treatment programs across the 4,000-square mile county, and 30 mobile crisis support teams to respond to emergencies, sometimes while partnered with sheriff’s deputies or police officers.

Thanks to a $40.1-million state grant, however, those services will soon be expanded. The board voted to double the number of its urgent care centers, and potentially multiply its crisis residential treatment programs tenfold. It authorized creating 11 more mobile crisis support teams.

In an interview, Mental Health Director Marvin Southard said only those who are not considered a danger to society would be eligible for diversion.

“If somebody has committed a serious crime, they need to pay the consequences,” he said. “Whether they happen to be depressed is really beside the point.”

DMH also has mental health professionals embedded in 22 courthouses, but Lacey acknowledged that some prosecutors and public defenders don’t utilize their services or even know they exist.

She said officers of the court, as well as law enforcement officers, need additional training to ensure the mentally ill receive treatment, instead of ending up behind bars. She said that training would be the “short term” goal of the Criminal Justice Mental Health Project.

County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky believes that having Lacey spearhead the county’s diversion efforts is a “game changer.”

“It’s one thing for a non-law enforcement officer to advocate for this sort of thing, but it’s another when one of the chief law enforcement officers in the county — in this case, the D.A. — gives this the imprimatur of acceptability,” he told her after her recent testimony.

“I think this will be a real revolution for the county,” he said. “And I hope that we have the political will to get it done.”

In an interview after her board appearance, Lacey said she sees diversion programs as being “right within my mission.”

“My mission is to seek justice,” she said. “The stories of people who have loved ones in jail, or who have been put in jail themselves while mentally ill, just speaks to me personally.”

Posted 11/20/14

Help isn’t just a text away (yet)

October 23, 2014

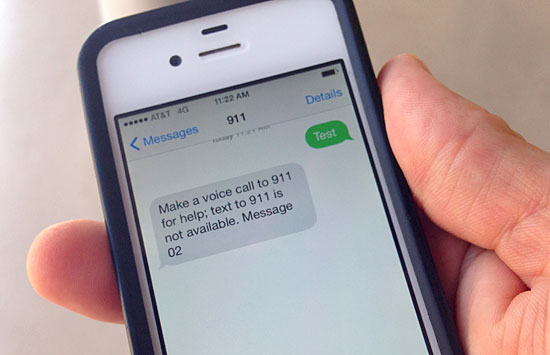

“Make a voice call to 911 for help; text to 911 is not available.”

That automated message isn’t what you want to receive during an emergency, when seconds count. But for now, that’s what people in Los Angeles County get when they send a text to 911.

That could be changing with the advent of new systems—called “text-to-911” and “Next Generation 911”—which would allow people to send texts, and eventually pictures and videos, directly to emergency dispatchers. On Tuesday, acting on a motion by Supervisor Don Knabe, the Board of Supervisors directed the county’s Chief Executive Office to explore ways of implementing the new technology.

The ability to receive photos and video could make a big difference for public safety workers, helping solve crimes and potentially saving lives, said Lieutenant Antonio Leon, who manages the Sheriff’s Department data network.

“The dispatcher would look at it and provide information to deputies in the field,” Leon said. For example, if a robbery has occurred and officers have a basic description of the suspect, “a video can corroborate that and provide additional information like height, facial hair or a unique item of clothing.”

And in the case of an active shooter situation, he said, law enforcement could get a head start on sizing up the situation and coordinating resources accordingly.

“Right now if something like a school shooting happens you’ll see people post things to social media, but it doesn’t become available [to authorities] until a long time after,” Leon said. Someone who now posts a photo to Twitter or Facebook could in the future send those images directly to a dispatcher, along with data indicating where it was taken. “Maybe there are people that are injured. Now you know you’re going to need medical resources ready to go, or maybe you just have to send the SWAT team in right away instead of waiting.”

Basic text-to-911 “should be capable of deploying in short order,” Leon said. But Next Generation 911—which goes beyond basic texting to include photos and videos, and the ability to pinpoint a user’s location via GPS— won’t be available until further down the road. First, the Sheriff’s Department and other first responder agencies must upgrade their technology. Another obstacle is funding, since local governments’ emergency call center equipment is provided by the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services. Karen Wong, the agency’s assistant director for public safety communications, said Next Generation 911 could be available statewide within five years—but only if funds can be found to make it happen.

Consumers’ increasing reliance on texting and communicating with smartphones has, ironically, dried up the state’s main source of funding for the program—fees attached to long distance calls from land lines. “The state account does not have enough money and it is actually depleting because it is based on interstate calls in California,” Wong said.

California’s program is part of a national effort being coordinated by the Federal Communications Commission. On August 8, the agency adopted an order requiring all text messaging providers to deliver emergency texts to any public safety agency that requests them. So far, a few dozen agencies in 12 states have launched text-to-911 and about 15 agencies have switched to full Next Generation 911, Leon said.

Still, most agencies aren’t quite ready to receive text messages, photos or videos just yet.

“If we do this right, this thing will be real nice and something we can rely on,” Leon said. “But it’s going to take a lot more work to get it going.”

It's not possible yet, but the county is studying ways to enable people to text emergency dispatchers.

Posted 10/23/14

Piloting a path away from jail

September 18, 2014

Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky announces the creation of a new jail diversion program, with Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey, in the yellow jacket, among those in attendance.

Confronting a jail system packed with rising numbers of mentally ill inmates, an unprecedented coalition of criminal justice and social services agencies have rallied behind an initiative that stresses rehabilitation over punishment for certain low-risk offenders and holds out the promise of reduced recidivism.

Eleven agencies—including the Superior Court and the offices of the district attorney, city attorney and public defender—are collaborating in the pilot project, orchestrated by Los Angeles County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky as a way to provide chronically homeless and severely mentally ill individuals with a carefully proscribed path out of jail and into recovery.

“I believe this is a more intelligent way of dealing with people like this, rather than putting them in jail, which is a far more expensive and less effective way to address mental health issues,” Yaroslavsky said during a Wednesday news conference at the Van Nuys courthouse.

“This program is going to start here, at the Van Nuys Courthouse and at the San Fernando Courthouse, but it could easily be placed in Compton, in Pomona, in Inglewood, Santa Monica, anywhere,” said Yaroslavsky, who allocated nearly half of the initiative’s $750,000 price tag from his district’s discretionary funding.

Among those who stood alongside the supervisor for Wednesday’s announcement was Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey. In recent months, she has become the leading proponent of alternative sentencing for low-risk mentally ill offenders, whom she says have little chance of success inside the county’s overcrowded lockup.

Lacey called the incarceration of such defendants, who suffer from bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress syndrome and other mental illnesses, an “unconscionable waste of human life and money.”

The new Third District Diversion and Alternative Sentencing Program will, under a series of specific conditions, provide 50 eligible participants with a variety of wraparound services—including permanent supportive housing and mental health treatment—intended to keep them off the streets, out of jails and emergency rooms, and put them on a path to self-sufficiency. Those services will be arranged by the non-profit San Fernando Valley Community Mental Health Center.

Under the program’s protocols, prosecutors and public defenders will collaborate with psychologists to identify severely mentally ill—but nonviolent—chronically homeless individuals eligible for the program’s shelter, counseling, medication management and other services, including employment and vocational assistance. A judge must approve the defendant’s participation.

Eligible misdemeanants will undergo treatment for 90 days and pay restitution, if necessary. Charges will be dismissed after the successful completion of the program. Otherwise, the criminal case will proceed.

Eligible felons, meanwhile, will be required to plead guilty or no contest to the charges against them and undergo treatment for 18 months, with case managers and probation officers regularly checking their progress. They also will have to pay restitution.

“What I like about this program is it does have a lot of leverage with participants,” said Adrian Sheff, director of adult and older adult programs at the San Fernando Valley Community Mental Health Center. “They’re not just being diverted from jail and told to bring a note back from their treatment provider to say they completed the program. Instead, there are ongoing reports, feedback with the court and probation and other measures to ensure they won’t wind up back in jail or commit new offenses.”

City Atty. Mike Feuer, whose office prosecutes misdemeanors, agreed during Wednesday’s event that jail is the wrong place to deal with severe mental illness. He said the pilot program’s more “innovative and humane” approach will keep neighborhoods safer.

Said Superior Court Presiding Judge David Wesley: “It is sometimes in the best interests of the public, and of mentally ill offenders, to divert someone from the criminal justice system.”

Los Angeles County Mental Health Director Marvin Southward said he hopes the pilot program marks the beginning of lasting reforms in the way the criminal justice system treats the severely mentally ill and chronically homeless.

“I think we have to show that by investing in an intensive program like this, we could produce good enough outcomes and save enough money that it’s worth spreading this model to other places.”

Posted 9/18/14

From boot camp to home base

September 11, 2014

A probation official at the old central command center, where the camp's open dorms were supervised.

When bulldozers rumble into Camp Vernon Kilpatrick in Malibu, they will not only demolish an obsolete juvenile corrections facility but make way for an innovative approach to rehabilitating delinquent youths.

The Los Angeles County Probation Department is turning away from traditional methods that focused on control and punishment. Instead, it’s gradually adopting a model that emphasizes mentoring and a sense of community.

“It’s about building relationships and trust,” said Sean Porter, a director with the department’s Residential Treatment Services Bureau.

“There’s a saying: (the youths) won’t care what we think until they think we care about them,” Porter added. “The more time we spend with the youths, and convey compassion and genuine interest in them, the more they’ll listen to us.”

On Friday, probation officials, along with Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, will hold a ceremony to kick off the demolition of Camp Kilpatrick’s aging dormitories, classrooms and gym —only the kitchen and pool will be left intact — while plans for a modern facility are finalized. The project’s completion date is still to be determined.

Originally built as a barracks in 1962, Camp Kilpatrick had an institutional configuration, with bunk beds arranged in rows against cinderblock walls, exposed showers and toilets, and spaces designated for solitary confinement.

It was essentially a boot camp, and Porter believes such an approach tends to produce only short-term benefits

“It’s temporary,” he said. “Unless you change the way the youths think, you’re not going to change the way they behave.”

Probation Chief Jerry Powers is determined to reform the system by emulating some of the techniques used by Missouri’s Division of Youth Services.

The so-called Missouri Model puts youths in small groups with a more home-like—as opposed to jail-like—environment, supervised closely by supportive probation officers, social workers, teachers, psychologists and other professionals.

The approach has dramatically lowered juvenile recidivism rates in Missouri, and jurisdictions in New York, New Mexico, Washington D.C. and California’s Santa Clara County have created their own versions of it.

Powers’ $48-million vision for Camp Kilpatrick calls for tearing down the dilapidated dormitories and building cottages for “core groups” of 8-12 youths.

They would attend classes, eat meals, and engage in counseling sessions and other activities together. The cottages would be furnished with comfortable beds and other amenities, and have lots of natural light and fresh air.

In addition, there would be an on-site doctor’s clinic, daily nursing services and extended mental health clinician coverage—all unique to the Los Angeles Model.

Powers said the goal is to help the youths feel secure, while developing a sense of responsibility, accountability and community.

“Aligning the new facility with new treatment and educational approaches will translate to reduced recidivism, increased academic achievement, and better employment opportunities,” he wrote in a letter to the Board of Supervisors in May.

To date, the board has approved a $41-million budget for the project, about three-quarters of which has been raised through state grants.

Angela Chung, a policy associate with the nonprofit advocacy group Children’s Defense Fund, is excited about the proposed changes.

“I think this is a chance for Los Angeles to be ahead of the curve and move toward a more healing model,” she said.

Porter said if core groups are like a sports team—with their probation officer acting as their coach—Camp Kilpatrick already has a track record of success.

Its winning football team inspired the movie Gridiron Gang, with Porter portrayed by actor/wrestler Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson. Its basketball team almost won a regional championship, while the soccer program has produced a league MVP.

“We’ve used sports to teach self-discipline and the value of hard work, and to develop self-esteem,” Porter said.

“When the youths walked out of the camp and back into their communities, their shoulders weren’t slumped down and their head wasn’t hanging because they were able to accomplish something, and they knew they could do more.”

The vacant Camp Kilpatrick will be razed and replaced with a modern facility and a change of philosophy.

Posted 9/11/14

Jail alternatives gain momentum

July 31, 2014

Thousands of mentally ill inmates are in L.A. County jail cells, making succesful treatment unlikely.

In recent months, a single word has dominated Los Angeles’ criminal justice debate, one that’s positioned the county’s top prosecutor as a champion of reform and consumed meetings of the Board of Supervisors, including this week. The word: diversion.

District Atty. Jackie Lacey, in her first term, is at the forefront of a growing, multi-jurisdictional initiative to provide community-based diversion to thousands of county inmates who suffer from mental illness and can’t be effectively treated behind bars. This, she argues, creates a cycle of recidivism that’s harmful to the individual and that ripples through society. Lacey is expected to present her recommendations in September to the supervisors, who’ve also been confronting the diversion issue.

In early June, the U.S. Department of Justice, noting a rise in jail suicides, criticized the county’s handling of mentally ill inmates and said it was prepared to seek federal court oversight of the lock-up, which is operated by the Sheriff’s Department. But the agency made a point of praising the county for its recent efforts to explore diversion for low-risk offenders.

Diversion also played a key role in the board’s recent debate to raze the old Men’s Central Jail and build a new one designed to double as a treatment facility for inmates with mental health needs. At a cost of at least $2 billion, Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky cast the only dissenting vote, arguing that community-based diversion programs should have been fully explored before the county committed to its most expensive construction project ever.

On Tuesday, the board again tackled the topic—this time debating a motion by Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas to, among other things, commit $20 million for a “coordinated and comprehensive” diversion program for mentally ill inmates. The board, he argued in his motion, “needs to demonstrate its financial commitment to diversion.”

Although supervisors expressed strong support for placing low-risk mentally ill inmates in community-based diversion programs, the majority 0pposed earmarking money without a spending plan. The better way, they said, was to see what Lacey recommends and then consider the funding during the board’s late September budget process.

“We would be making a huge mistake just throwing money at it and saying: ‘Look at us. Aren’t we great at diversion?’” said Supervisor Gloria Molina. “We need to be thoughtful. We need to have a plan.”

Supervisor Yaroslavsky said that nearly a decade ago, the county set aside tens of millions of dollars to combat homelessness. But like now, he said, there was no blueprint for spending it. “We were so excited to have the money to set aside,” he said, “we forgot to develop a plan. And so we shouldn’t make that mistake a second time.”

“We need to have a road map,” Yaroslavsky continued. “I have confidence that under the leadership of the district attorney, with the participation of all of us, we can develop something like that.”

The board voted to consider the motion’s funding element during supplemental budget deliberations in late September.

Posted 7/31/14

Searching a web of clues

May 30, 2014

Scouring social media sites, sheriff's researchers have put a serious crimp in hundreds of teen parties.

There are no bigger party poopers in town than a tiny team of web savvy sleuths in the Sheriff’s Department, who patrol social media looking for potential trouble, including jammed-to-the-rafters raves that promise alcohol and drugs to underage partyers, particularly teenage girls.

During the past few years, the little-known unit has “intercepted” and helped block 1,000 parties before they even got started, according Cmdr. Mike Parker, the department’s leading authority on social media and online communications.

Sometimes, Parker said, deputies are dispatched directly to doorsteps, where they warn adults that they’ll be arrested for contributing to the delinquency of a minor should the party go off as advertised on Facebook, Twitter or other social media sites. Other times, the deputies will join an online conversation among would-be celebrants with this buzz-killing greeting: “Thanks for the invite. See you there!”

As a result, the department’s proactive Internet strategy has short-circuited the assaults and neighborhood disruptions that often accompany raves—and saved public dollars that otherwise would be spent on patrols and prosecutors.

“If it’s being shared for all the world to see,” Parker said of the party promotions and other postings that raise red flags about public safety, “then it’s the social equivalent of standing outside of school with a bullhorn. There’s no expectation of privacy. But if, as a law enforcement officer, you’re pretending to be someone else, that’s where you get into that danger zone of Big Brother accusations.”

The notion of proactively scouring the web for possible crime clues has emerged on the public radar in a very different context in recent days. In the aftermath of last Friday night’s Isla Vista murders, sheriff’s officials in Santa Barbara have been questioned about whether they should have known more about the killer with whom they’d had earlier contact and who had posted provocative videos and rants. Authorities there have acknowledged that, while they were aware of Elliot Rodgers’ videos, they did not view them.

In reality, most local police agencies have yet to explore the potential of the Internet as a preemptive crime-fighting tool, one that requires training and staffing, just like any other specialized law enforcement job, says Parker, who emphasizes that he is not second-guessing Santa Barbara police.

“It’s not like a 911 call that you’re obligated to respond to,” Parker said the other day, as he prepared to deliver a social media presentation at the county’s annual leadership conference. “It’s a very different challenge. You have to go out and hunt, and you have to want to do it. You have to pride yourself on finding things.”

Parker, a 29-year-veteran of the department, is a nationally-recognized leader of that effort. Until his recent promotion as commander of the north county patrol division, he headed the Sheriff’s Headquarters Bureau, which included the new Electronic Communications Triage Unit. Today, he’s its consultant and evangelist.

The unit has two full-time members and some part-timers whose web work extends far beyond raves. Using “keyword” and “geo-tag” searches, they target issues that could touch a broad swath of society or a single family—from preparing for a flash mob that’s been promoted online to trying to rescue a suicidal teenager. Parker shared this story:

After an assault with a deadly weapon occurred in a particular neighborhood, one of the unit’s members began searching the web for postings by witnesses that deputies could interview. In the process, she discovered a posting by a neighborhood girl who was threatening to take her own life. She’d posted pictures on Instagram and revealed she’d been cutting herself.

A street sign in the background of one of the photos allowed deputies to zero in a possible home. On the first visit, no one answered. The second time, mother and daughter were both there, Parker said.

“That’s when the mom found out that her girl was cutting herself and wanted to kill herself,” he said, adding that the mother knew her teen was depressed but did not understand the depth of her despair. The girl was voluntarily admitted for mental health care.

Asked whether the deputies’ intrusion into the girl’s life could be seen as a breach of her privacy rights, Parker responded:

“A key element is that she is sharing what she is doing for the entire world to see, including a potential predator, who would see her vulnerability as something to exploit. Psychologists would call her actions an open cry for help. We heard her cries and came to help. Too often, people are afraid to get involved…and sadness and regret often follow.”

“We could probably keep someone busy fulltime just working on people who want to hurt themselves,” Parker said.

Looking to an increasingly digital future, Parker said he believes that a robustly staffed regional center should be created to help law enforcement officers scour the web for open source material that could produce investigative leads at any time of day, just like other kinds of multijurisdictional task forces.

“As I say that, I know civil libertarians get concerned,” he admitted. But he argued that people put information into the public domain for the world to see—“and I’m a member of the world.”

Cmdr. Mike Parker has been leading the way in using the Internet to proactively identfy potential trouble.

Posted 5/30/14

Board clears way for $2B jail

May 8, 2014

The grim Men's Central Jail will be razed for one that focuses on the needs of mentally ill inmates.

On the outskirts of a gentrifying downtown Los Angeles, where trendy eateries and pricey lofts are drawing a wave of hip urban pioneers, there sits a residence of a vastly different sort–“an antiquated, dungeon-like facility,” home to some 5,000 people, many of them mentally ill.

That’s how a blue-ribbon citizen’s commission in 2012 described the county’s notorious Men’s Central Jail, which has been around since the Kennedy Administration. More recently, the so-called MCJ was ground zero in the Sheriff’s Department brutality scandal that led to the indictments of 20 deputies and the departure of Sheriff Lee Baca.

For a decade, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors has been debating various plans to replace the old lockup with one that reflects the latest thinking in modern jail construction and management. Each time, the price climbed. The stakes were rising, too, as the federal government intensified its oversight of how the county was providing constitutional care for thousands of inmates with mental health problems.

So on Tuesday, under increasing pressure to act, a divided board set in motion what promises to be the most expensive construction project in the county’s history. It approved a nearly $2 billion plan to replace Men’s Central Jail with a facility designed to confront the unique architectural and staffing requirements for treating mentally ill inmates in county custody.

The board majority, which also voted to move forward the renovation of Mira Loma Detention Center in Lancaster to house women, picked one of five options for the new downtown jail provided by Vanir Construction Management, which was hired as a consultant by the supervisors. The company will not be a bidder on the project.

While there was no disagreement among board members about the need to replace the Men’s Central Jail, the potential price of the undertaking drew strong warnings from Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky. He cast the lone vote against authorizing the expenditure of $30 million to begin design work and an environmental review of Vanir’s “Option 1B.” (Voting in favor of the plan were Supervisors Don Knabe, Gloria Molina, and Michael D. Antonovich. Mark Ridley-Thomas abstained.)

Yaroslavsky argued that the board should have been given alternatives to incarceration that might reduce the number of mentally ill inmates in the new jail, thus possibly lowering the construction and operating costs borne by taxpayers.

“I think I have been, as a member of this board, somewhat shortchanged by not having that information available to me as I’m being asked to make a decision—a $2 billion decision,” Yaroslavsky said, adding: “All of us have been around long enough to know that if you’re telling us it’s $2 billion today, it’s not going to go down. It’s only going to go up.”

Yaroslavsky urged the board to delay a vote until more information on diversion programs for the mentally ill was provided, rather than being forced to decide solely on a series of construction scenarios. He also noted that District Atty. Jackie Lacey was leading a high-powered task force on mental health and substance abuse diversion that could inform the board’s ultimate decision.

Testifying before the board, Lacey said that since a big chunk of the new jail’s cost is for the mentally ill, “you should know that there’s a committed group of professionals …who are looking for alternative ways to address this issue. We’re serious about it, and I’m optimistic.”

Assistant Sheriff Terri McDonald, who oversees custody operations, acknowledged the importance of increasing capacity for inmates placed in community diversion programs. “I don’t think the right solution is just build, build, build, build. It’s too expensive. It’s not sustainable.”

But, she said, such efforts must “run along parallel tracks” with the design and construction of a new jail, which is essential for the inmates and the county’s legal position with the federal government.

Supervisor Antonovich, who, with Molina, pushed the vote forward, agreed: “If we don’t act,” he said, “the choice will not be ours, but up to a receiver who will force us to act, at a much higher cost.”

Posted 5/8/14

New sheriff writes a new chapter

April 17, 2014

When former Sheriff Lee Baca announced his surprise resignation to a crush of reporters in January, he closed with a heartfelt recitation of the agency’s “core values.”

“As a leader of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department,” he said, his voice wavering with emotion, “I commit myself to perform my duties with respect for the dignity of all people, integrity to do right and fight wrongs, wisdom to apply common sense and fairness in all I do, and courage to stand against racism, sexism, anti-Semitism, homophobia, and bigotry in all its forms.”

It was not the first time the sheriff had publicly, solemnly recited the code. He’d long ago committed the words to memory and had spoken them often during the ups and downs of his tenure—especially during those final months when he and his department were under siege for alleged deputy brutality in the jails.

But now Baca is gone. And so, too, is his code of core values.

On Monday, interim Sheriff John Scott sent out an all-hands email announcing the creation of a new statement, one containing “the same deeply-held values” but expressed in a new way. Scott explained that he’d reached out to a committee of deputies, sergeants and professional staffers to craft the new statement, with its extra emphasis on professionalism, compassion and accountability—words that were absent in Baca’s code.

“I will hold myself accountable for serving our Department and the public in a manner consistent with these values, and I will, in the same way, hold each of you accountable for your actions,” Scott pledged in his department-wide email.

What went unsaid was the subtext. Many in the rank-and-file had come to view the old code as a collection of empty vows, violated by some at the top of the organization, Scott explained in an interview.

The old code had become an example of, “do as I say, not as I do,” Scott said. “That was the driving force [behind the change]. The code should not be just nice words on a wall. It should reflect values you live by in the light of day and in the shadows of darkness.”

The new code was built around six words (one for each point of the badge) that the 12-member committee concluded best described how department members should conduct themselves in the pursuit of their mission, Scott said. Those words were then woven into this short statement:

“With integrity, compassion, and courage, we serve our communities—protecting life and property, being diligent and professional in our acts and deeds, holding ourselves and each other accountable for our actions at all times, while respecting the dignity and rights of all [emphasis included].”

Beyond its statement of guiding principles, the new code also is meant to send a broader symbolic message.

Since his temporary appointment by the Board of Supervisors in late January, Scott has wasted no time dismantling remnants of the Baca Administration that he believes had damaged morale, undermined the department’s effectiveness and broken the public’s trust.

Among other things, he’s shaken up the management ranks, created new internal controls and even banned cigar smoking on a patio at the agency’s Monterey Park headquarters that was frequented by friends of the top brass and had come to represent clubbiness and exclusion.

These actions, like the rewritten statement of core values, will let the troops and the communities they serve know that “this is a new beginning,” said Scott.

Scott has said he wanted to institute these kinds of changes nine years ago, while serving in the department’s command staff. But unable to get Baca’s buy-in, Scott said, he retired in 2005, later becoming the No. 2 official in the Orange County Sheriff’s Department, where he has led reform efforts in that once-troubled agency.

As part of Scott’s deal with the Board of Supervisors, he’ll return to Orange County after voters here elect a new sheriff either in the June primary or a November runoff. The board did not want an interim sheriff to be distracted by a divisive political campaign at a time when the department needed clear, focused direction.

The day after his appointment, Scott said, he shared a private meal with Baca to talk about the future of a department to which both had devoted decades of their lives.

“I told him, ‘There’s going to be some things I do and it’s going to be sensitive to you. It’s not personal. It’s not about me, it’s not about you. It’s about the department.’ ”

Posted 4/17/14

Maximizing our “big gulp”

March 6, 2014

Here’s a factoid for those who think last week’s storms are water under the bridge now: Thanks to Los Angeles County’s flood control system, about $18 million worth of that rain is in the bank.

Los Angeles County Public Works Director Gail Farber reported this week that the county’s flood control infrastructure—sprawling, complex and generally taken for granted by Southern Californians—managed to collect and store some 18,000 acre-feet of rainfall by the time the skies cleared.

That’s enough water to supply 144,000 people for a year—roughly the population of Pasadena. Or, for Westsiders, a year’s worth of hydration for everyone in Santa Monica, the Pacific Palisades, Topanga Canyon and Malibu combined.

At about $1,000 per acre-foot for imported water, that’s good news, Farber told the Board of Supervisors on Tuesday. But in the midst of this drought, even more of that precious precipitation could have been saved had county dams not been clogged with dirt, sand and gravel from prior storms.

Instead, Farber said, water at Santa Anita Dam and Devil’s Gate Dam was released to maintain a safe capacity and prevent flooding.

“Had we more capacity behind our dams,” says Farber, “we could have captured more rain than we did.”

The storms dumped nearly a foot of rain last week on parts of Los Angeles County, raising water levels by as much as 36 feet at some of the county’s 14 dams. Though eagerly anticipated in this water-starved year, the rain also brought the threat of mudslides in foothill neighborhoods where brushfires have hit hard in recent months.

County workers had been out in force, working with surrounding municipalities and first responders to buttress vulnerable streets and help homeowners get ready, and were on hand round-the-clock as the storms hit.

Farber said the Department of Public Works alone “had more than 325 employees out there day and night, working 12-hour shifts in the pitch black with mud and debris flowing, and the rain coming down, and snow in the mountains, and hail sometimes.”

For all of that, the downpours scarcely made a dent in the three-year drought that has been withering the region, says Deputy DPW Director Massood Eftekhari.

“We’ve only accumulated 22 percent of what we normally accumulate, compared to prior years,” Eftekhari says. “We still have to conserve and collaborate to capture and utilize every drop we get.”

To that end, Public Works officials have been focused on maximizing the system’s capacity to better store rainwater when future storms hit. The county’s dams are set up not just to prevent rains from inundating neighborhoods in the flats and foothills, but also to collect storm water. That water later is released gradually onto massive spreading grounds where it percolates into the underground aquifers that supply about a third of L.A. County’s drinking water.

But each accumulation of rain also brings an accumulation of sediment and runoff. That sediment—hundreds of thousands of cubic yards of gunk in a typical year, enough to fill the Rose Bowl several times over—settles in dams and debris basins, and takes up space that otherwise would hold valuable rainfall.

Typically, that gunk gets trucked out over time by Public Works crews who dispose of it in designated “placement sites”, landfills and rock quarries—an epic task that, until recently, followed a time-honored schedule. After the historic 2009 Station Fire, however, so many tons of charred debris washed into the system that the county’s entire sediment management plan had to be recalculated, says Farber.

Now, she says, at least four county dams—Devil’s Gate, Big Tujunga, Pacoima and Cogswell—have been put on an accelerated sediment removal schedule. Devil’s Gate, which is near Pasadena, is first in line, with an environmental impact report already underway, and Pacoima will be soon to follow.

That intensified need to make room in the system has drawn some fire from neighborhoods near some of the dam sites. Though they have the most to lose should the clogged dams overflow, they also stand to suffer the greatest inconvenience from the truck traffic inherent in removing millions of cubic yards of muck.

As communities around the dams measure their risk against the potential for upheaval, the officials noted that the county will be working with state and federal agencies to come up with efficient ways to capture more storm water and prepare for future storms.

Meanwhile, they remind, this is no time to let our guard down.

“This was a good-sized gulp, but the drought still is not over,” Eftekhari says.

Posted 3/6/14

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink