By Car

Love and hate in the express lane

April 24, 2014

When it was time for the public to finally be heard on Los Angeles’ new freeway toll lanes, Metro got an earful.

“I love the Metro Express Lanes!!!!! We should have them throughout the city.”

“These fast track lanes have turned into nothing but Lexus Lanes.”

“Express Lanes are the best thing ever to happen to Los Angeles freeways.”

“The Express Lane program is an absolute joke.”

“Please Please Please…expand the express lanes!!!!!!

“ADMIT IT—IT’S A FAILURE!!!!

Metro had asked for the public’s take in March as part of a broad analysis to help the agency’s board of directors determine whether the “high occupancy toll lanes” on two of Los Angeles’ busiest freeways—the 110 and 10—should be made permanent. And on Thursday, the directors gave a unanimous thumbs-up to extending the experiment, despite the deeply divided motoring public reflected in the more than 700 emails the agency received.

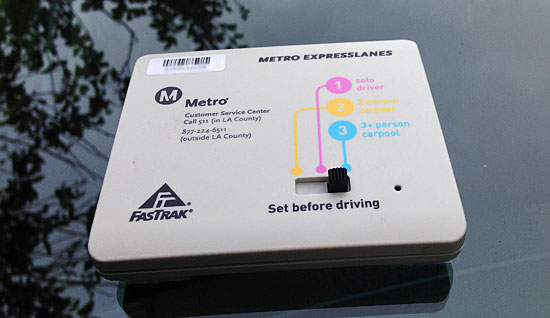

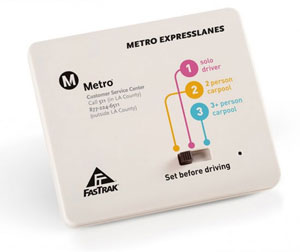

The federally-funded program lets solo drivers, who pay a toll, share lanes with carpoolers, who can continue to drive in them for free, with one important and controversial caveat: everyone must have an electronic device called a transponder to use the “ExpressLanes.” That requires putting $40 into a “pre-paid” toll account, unless a person’s income qualifies him or her for assistance.

Stephanie Wiggins, Metro’s executive in charge of the toll lanes, presented the analysis to the board on Thursday. She said in an interview that she’s “never, never, never” had a job that has attracted so much public heat. “People really love them,” Wiggins said of the new lanes, “or they really hate them. There’s no in-between.” By overwhelming majorities, according to a Metro survey, those who obtained transponders are happy and those who didn’t are not.

Metro director Mike Bonin, who also is a member of the Los Angeles City Council, lauded the pilot program but acknowledged, like others on the board, that it is still a work in progress. “We’re in the breaking eggshells phase of making an omelet,” he said.

It’s not surprising, of course, that the dramatic changes would generate consternation and confusion among motorists who for decades have been freely using the carpool lanes—for 39 years on the 10, east of downtown Los Angeles, and 15 years on the 110, which slices through the heart of the city.

Statistical measures compiled by federal transportation officials in advance of the board’s vote have done little to settle the debate. They can be used by either side to make a glass-half-full/half-empty argument.

The pilot program was intended to improve traffic flow in both the toll and “general purpose,” or free, lanes, while also encouraging the use of transit alternatives, such as the Silver Line buses that travel along the toll lanes. So far, bus ridership has jumped but traffic times are not much different than before the experiment, according to a recent analysis by an independent firm hired by the Federal Highway Administration. Some drive times are slightly faster since the tolls went into effect, while others are slower, depending on the specific hours studied during peak morning and afternoon traffic.

Wiggins acknowledged that “the numbers, on their face, look marginal.” But she said there’s a clear bright spot, too: Solo drivers who’ve moved from the free lanes into the toll lanes have saved more than 17 minutes on some of their drives. And for those who haven’t changed their behaviors and remain in the free lane, they’re not really any worse off than they were before, she said. “And that can be perceived as a positive.”

What’s more, Wiggins noted that the $18 million in net toll revenues generated since the pilot began has far exceeded early projections. That means more money can be reinvested in transit improvements and inducements along the freeway corridors and that no public subsidies will be necessary in the future because the project is raising enough money to be self-sustaining.

As of February, some 260,000 transponders have been issued by Metro, well above the 100,000 that had been set as an initial goal—a fact that prompted board member and L.A. County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky to remark: “People are voting with their cars.”

Wiggins also reported to the board that, in the future, Metro will work even more closely with the California Highway Patrol to crack down on scofflaws who drive in the lanes without transponders and to ticket solo drivers who cheat the system by setting their transponders to get a free ride by claiming multiple people are in the vehicle.

One of the most controversial elements of the toll lanes project had been the initial imposition of a $3 monthly “maintenance fee” on people who purchased transponders but who used the toll lanes fewer than 4 times a month. The fee was intended to recoup a charge levied for each transponder on Metro by the toll lane’s private operator.

To legions of travelers, it seemed unfair that anyone should be charged for not using something. To encourage drivers to participate in the toll lanes experiment, the Metro board last year waived the fee for Los Angeles County residents, who represent 86% of account holders, according to Wiggins.

On Thursday, the Metro board attacked the issue again, this time voting 8-3 in favor of a motion by director and L.A. County Supervisor Gloria Molina to impose a $1 monthly fee on everyone with a transponder, no matter how often they use the toll lanes. In this way, she argued, Metro will no longer be underwriting the fee and will have some $2 million more annually to reinvest in the system and in transportation benefits in communities along the 10 and 110 freeways.

Now that the toll lanes are becoming a permanent part of Los Angeles’ famous (infamous?) car-centric landscape, Wiggins said it’s crucial that Metro do a better job of communicating the value of the program to motorists.

A top priority, she said, will be to educate the public on how transportation is funded.

“We didn’t do ourselves any favors,” she said, “by naming them freeways because we know freeways aren’t free.”

Posted 4/24/14

Toll roads on a roll, minus fee

October 24, 2013

With drivers flocking to the ExpressLanes pilot project and revenue from the toll roads exceeding projections, Metro’s Board of Directors voted to continue to waive a controversial maintenance fee for L.A. County drivers who use the lanes only occasionally.

The board’s unanimous vote means that the $3 monthly maintenance fee will continue to be dropped for infrequent users at least until the pilot program wraps up early next year. The waiver had been set to expire on Friday, Oct. 25.

The toll roads pilot project, funded by a $210 million grant from the United States Department of Transportation, is set to conclude on Feb. 23, 2014, but if successful could be made permanent.

At the Metro board meeting Thursday, a motion to permanently drop the maintenance fee levied on occasional users was sent back to committee. Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, a board member who supports dropping the occasional user fee as a matter of fairness, argued in favor of moving proactively to make the waiver permanent. Given the overall boost in toll road revenue and the increase in drivers signing up for the transponders needed to take part in the program, revenue lost by waiving the maintenance fee is minimal, he said.

“Revenues generally on the ExpressLanes are far in excess of what anybody had anticipated,” Yaroslavsky said. “What we’re finding now, I believe, is that more people are signing up for [ExpressLanes] transponders because they haven’t been required to pay this fee.”

However, Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas said it was too soon to tinker with the program, and Supervisor Gloria Molina said there shouldn’t be a “rush to judgment” on dropping the fee before there’s a fuller study of how that might affect revenue available to reinvest in transit improvements in communities along the ExpressLanes corridors. “I don’t think we should make it permanent,” she said.

Stephanie Wiggins, who is heading up the pilot project for Metro, said that dropping the maintenance fee would cost the agency $1.5 million a year. But, she said, that is offset by the overall spike in revenue: By the end of last month, the ExpressLanes already had generated more than $20 million in gross revenues, well ahead of the $18 million to $20 million anticipated by the project’s conclusion.

According to Metro forecasts, between $16 million and $19 million of that would be available for reinvestment for transportation improvements within the corridors, Wiggins said.

In addition to the unforeseen revenue, far more people are using the program than the 100,000 originally anticipated. As of last month, 176,243 were participating, with 85,102 of those deemed occasional users because they make three or fewer trips a month on the ExpressLanes.

The first ExpressLanes opened on an 11-mile stretch of the 110 Freeway last November. A second stretch on the 10 Freeway from Alameda Street in downtown Los Angeles to the 605 Freeway opened in February.

All ExpressLanes motorists—including carpoolers—are required to obtain a FasTrak transponder and to create an account from which tolls are deducted. Except for carpoolers, all users of the system pay to drive on the ExpressLanes, with amounts varying according to distance traveled and time of day. But, to the chagrin of many, only the occasional users were targeted with the monthly maintenance fee.

The board’s decision in April to temporarily lift the $3 fee had a beneficial effect, Wiggins said.

“Throughout the county, residents are benefiting from the five-month waiver,” she said, noting that the impact has been greatest among users in the South Bay, where the number of FasTrak accounts is highest.

Marianne Kim, representing the Automobile Club of Southern California, told Metro’s board that complaints to AAA about the program have gone down since the waiver went into effect.

Beyond the positive data on revenue and driver participation in the program, there also was some generally upbeat news on travel speeds in the two ExpressLane zones.

Average travel speeds on the northbound 110 improved year-over-year in both the ExpressLanes and the general purpose non-paying lanes next to them during morning rush hour, according to measurements made by Caltrans in May and June. During the afternoon rush hour, the southbound ExpressLanes also were moving faster than they did before the project, but the general lanes were moving more slowly—30.3 mph, compared to 34.7 mph during the same period in 2012.

On the westbound 10, morning rush hour speeds improved in both the toll and general purpose lanes. However, speeds in both kinds of eastbound lanes were down during the afternoon rush hour; traffic was said to be “significantly impacted” by a Caltrans construction project in the area.

Posted 10/24/13

A monthly toll road fee exits early

May 9, 2013

Even infrequent toll road users need a transponder, but they'll no longer pay a monthly maintenance fee.

Metro’s board of directors, taking aim at one component of a controversial ExpressLanes pilot project, voted Thursday to scrap for six months a maintenance fee levied on infrequent users of the toll roads, Los Angeles County’s first.

The board voted 7-4 in favor of a motion by Director and Los Angeles County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky to suspend the fees in the interest of fairness. Yaroslavsky’s motion, originally introduced for consideration in January and recently amended, applies to Los Angeles County residents who make four or fewer trips in the ExpressLanes each month. The motion only applies to local residents so that commuters who live in other counties—where monthly charges continue to exist—can’t go bargain-shopping here for their FasTrak transponders.

Everyone who uses the toll roads, which are located on the 110 and 10 freeways, is still required to have a transponder and to pay tolls if they’re traveling solo in the lanes. Carpoolers (two or more on the 110 Freeway, three or more on the 10 Freeway at peak hours) don’t have to pay any tolls but still must have a transponder in their vehicle. Until now, even carpoolers had been subject to the $3 monthly fee if they used the lanes infrequently.

“I think this is an unfair fee,” Yaroslavsky said, adding that he doesn’t believe exempting infrequent L.A. County users will have much of an impact on the program’s bottom line. Still, his motion sets a six-month time limit for the monthly fee exemption, during which Metro’s staff can gather data on how it affects usage of the lanes and the overall cost of operating them.

Stephanie Wiggins, who is managing the program for Metro, said she expects the number of ExpressLanes accounts to increase now that the monthly fee has been removed, drawing in motorists who “to date haven’t opted in because they feel the $3 fee is an impediment.”

Customers can obtain a transponder online, at AAA and Metro offices, as well as at Albertsons and Costco stores. They must then deposit $40 into an account from which toll charges and fees are deducted. (Some discounts are available.)

A Metro report said the agency started assessing the monthly $3 fees on February 24 and had collected a total of $14,175 from 4,725 infrequent users as of March 31. Overall, there were 107,921 accounts in the system in March, of which 27,620 were infrequent users who live in L.A. County.

The fees haven’t been the only issue to emerge since the first ExpressLanes started operating last November. Large numbers of citations have been issued, and while minimum average speeds in the new lanes have easily met or exceeded their 45 mile per hour target, speeds in the general purpose lanes next to them have dropped—which Metro said is to be expected as motorists get used to a new program.

Supervisor and Metro Director Mark Ridley-Thomas argued that it’s premature to “tinker” with the project by dropping the maintenance fee until the pilot period is complete in 10 months.

“It’s simply too soon,” he said. “I don’t know that it warrants intervention at this point.”

He voted against the measure, along with fellow supervisors and directors Michael D. Antonovich and Gloria Molina. Also dissenting was Director John Fasana, a Duarte city councilman.

Wiggins of Metro acknowledged that the agency has received complaints about the fee, but Ridley-Thomas and Molina said their offices had not received any.

Although she voted against changing the fee, Molina signaled she has some other issues with the program, starting with the fact that she had a tough time finding a place to get a transponder. “I seem to have gone to the only Costco that doesn’t have it.”

Logistics can also be a challenge, she added. “On the 10 [Freeway]…people don’t know how to get on it and utilize it, including myself.”

Posted 4/25/13

Street fighting man

October 4, 2012

The annual Oscar challenge: getting the limos to the Academy Awards safely and on time. Photo/Hebig via Flicrk

In this, the land of cars, all roads lead to Aram Sahakian.

With one false move, one slight miscalculation, he could bring L.A.’s traffic to a hellish halt. There are plenty of powerful jobs in Los Angeles government, but even the mayor takes a back seat to this street-smart guy when it comes to keeping the city moving.

Sahakian oversees special traffic operations for the city’s Department of Transportation and is thus responsible for mapping and implementing street closures for every big event in Los Angeles. Perhaps you know his work: Carmageddon (and next week’s sequel), the Academy Awards, championship parades for the Lakers and Kings, CicLAvia, presidential visits, the L.A marathon and, of course, The Rock’s journey to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

“I have an extremely understanding wife,” Sahakian says of the relentless hours and maddening deadlines of his job. “When you work for me, you better expect not to have much of a personal life.”

Now Sahakian and his small staff are preparing for one of their biggest logistical challenges—getting the retired space shuttle Endeavour from LAX to its new home at the California Science Center in Exposition Park. The shuttle is scheduled to arrive at the airport on Friday. On October 12, it will start a two-day journey to the Science Center, passing through Inglewood and into Sahakian’s turf.

Already, hundreds of trees are being felled to accommodate Endeavour’s 78-foot wing span. But that’s just the beginning. Sahakian says that once Endeavour actually gets rolling on its low-slung, remote-controlled transport, nearly 50 traffic signals along the route will have to be rapidly taken down as the shuttle approaches and then immediately restored after it passes—all in a single day.

“There’s no room for error,” says Sahakian, a 23-year veteran of the department. “If we get a picture in the Los Angeles Times showing the shuttle stuck because of a signal standard, this would not be good.”

In recent days, another complication has surfaced: Sophisticated tests of the streets along the route through South Los Angeles and downtown have revealed vulnerabilities beneath the surface, where sewer and water lines are located. These 14 areas, Sahakian says, could become sink holes under Endeavour’s 78 tons. This would not be good, either.

To fix the problem, Sahakian says that at least 150 plates of thick steel will be placed under the transport’s wheels to distribute its weight along the worrisome stretches. “And I’m not talking about a couple spots here and there,” Sahakian says. Details of the effort are still being worked out, but he expects the entire intersection of Crenshaw and Martin Luther King boulevards to be covered with steel.

Although the logistics of all this may seem dizzying, Sahakian says he has a bigger concern. “This is a cakewalk,” he says of the tightly choreographed traffic plan. “We can do this in our sleep. The big unknown is the crowd.”

Sahakian, who also oversees emergency response for his department, worries that thousands of people could turn out for the once-in-a-lifetime spectacle of the shuttle’s 12-mile urban journey. But this is not like artist Michael Heizer’s granite rock, which drew huge crowds during its slow-motion trip to LACMA, where it became the 340-ton centerpiece of “Levitated Mass.” In the shuttle’s case—because of its width and NASA’s desire to keep the public at a safe distance—there’ll be few places to stand, except at the end of streets that intersect the route or in designated viewing areas.

“What I worry about,” Sahakian says, “is a Rose Parade situation where we’ll have thousands of people out there with no place for them to park or see the shuttle.”

These are the kinds of scenarios that can haunt a planner’s waking—and sleeping—hours. Sahakian says that whether it’s the Endeavour project or the many others he’s constantly juggling, he may get an idea in the middle of the night. “Sometimes, I’ll send emails at 3 a.m. so I don’t forget,” he says.

Sounding more like an inspirational speaker (a la John Wooden) than a traffic engineer, Sahakian says his motto is: “Not planning is planning for disaster.”

Consider the Oscars. It is Sahakian’s job, among other things, to make sure that the fleets of limousines ferrying nominees and other VIPs don’t get tangled up outside the Dolby Theatre, formerly the Kodak, on Hollywood Boulevard. To that end, he has created a “serpentine” of concrete K-rail, through which each limo must slowly (but not too slowly) pass in an orderly fashion—a technique he’ll also be employing for this weekend’s Emmy Awards at Staples Center.

But the planning begins long before the stars emerge from their luxurious rides. “One of the most important elements of traffic planning,” he says, “is to know where people are coming from so you can facilitate the route.” That’s why his crew jotted down limo license plate numbers a few years back and studied their points of origin. Not surprisingly, most were arriving from the Westside.

Sahakian is not necessarily expecting any awards from the motoring public for his efforts. “If it’s a Lakers parade, they’re happy,” he says. “If it’s a 5K fundraiser, they’re not so happy.”

More often than not, he hears, “You guys are messing up the whole city.” Or maybe, “Whose bright idea was this?”

Still, he knows—even if the public doesn’t—that things could be a lot worse.

Last week, in his cramped office on the edge of downtown, Sahakian told a visitor that he’d recently worked with organizers of the hugely popular CicLAvia to change the date of its latest event, which was scheduled for the same October weekend as Endeavour’s journey. “Thank God CicLAvia agreed to move up its date” to October 7, Sahakian said with obvious relief.

A few hours later, however, his visitor got an email that spoke volumes about the man and his work. “Just to make it more interesting,” he wrote, “now I have Obama visiting on 10/7. Yes, Ciclavia :)”

Endeavour on its way to L.A., where Sahakian will help orchestrate its final journey. Photo/Los Angeles Times

Posted 9/19/12

When traffic takes a holiday

July 2, 2012

If you’re sticking around town this Fourth of July week, here’s a little something extra to celebrate:

Chances are your commute this week is lighter than usual, thanks to the 54% of holiday travelers who, according to the Automobile Club, hit the road early to get a head start on Wednesday’s Independence Day revelry.

Call it the mixed blessing of the mid-week holiday.

With Wednesday’s national celebration of the Fourth coming smack in the middle of the work week, many saw an opportunity to frontload their holiday by taking Monday and Tuesday off. (Or even starting out on the previous Friday, June 29.) Others are delaying gratification and opting to declare their independence from work on Thursday and Friday, thus backloading the holiday and spinning it into a 5-day weekend.

Even though the Auto Club estimates that 4.88 million Californians will be traveling for the holiday this year—a 5.2% increase from last year and more than any year since 2003—the staggered departure days appear to be diluting the traffic impact.

“We expect this is going to be a whole week of getaway days,” says Jeff Spring, spokesman for the Automobile Club of Southern California.

Whether they’re traveling or not, there’s plenty of evidence that folks are staying away from work in droves this week.

“You don’t need data,” Spring says. “You can just send some emails and wait for the auto-responses saying people are out of their offices.”

Danny Chung, media relations manager at Southern California Edison in Rosemead, says that although his workplace is going at full tilt, “everybody else seems to be taking it easy.”

“I drive in from La Verne and it has been a very light drive since Friday evening,” he says.

Government offices are closed Wednesday, and the holiday also will shut down local universities for a day in the middle of the week, making the summer session even quieter than usual. By Wednesday, UCLA will be “kind of a ghost town…except for the most diligent students wandering around,” says university spokesman Chris Stanton.

Even the California Highway Patrol, which declares the days on and around major holidays to be “maximum enforcement periods,” has determined that kind of stepped-up action will be needed only on Tuesday and Wednesday this week. By contrast, last July 4, which fell on a Monday, required a four-day maximum enforcement period starting the Friday before the holiday.

Still, don’t expect getting around town to be a picnic on Wednesday. Metro buses and trains will be running on a reduced holiday schedule, and traffic congestion is likely around popular recreation hotspots like the beaches and at major fireworks shows.

CHP Public Information Officer Saul Gomez, who reports on afternoon drive-time patterns for a number of Los Angeles TV and radio stations, predicted that Wednesday would be a “heavy traffic day.” Motorists should plan their route in advance, wear their seatbelts and designate a driver if they plan to raise a glass or two to Old Glory.

“It’s a very busy period,” Gomez says. “The weather is great and people tend to imbibe a little more than they would normally.”

Posted 7/2/12

How UCLA aced its traffic test

April 11, 2012

They said it couldn’t be done. Some said it shouldn’t be done. Yet to the surprise of many, it got done—a vast expansion of UCLA’s facilities without an equally vast increase in cars moving into and out of the campus.

In fact, more than two decades after the university embarked on a long range plan to add millions of square feet to its Westwood campus, the number of trips in and out of UCLA each day stands at its lowest point since such record-keeping began in 1990.

What’s more, it appears that the university’s culture of transportation has changed, too, with just under 53% of its employees driving alone these days—compared to nearly 72% in the county as a whole, according to the university’s latest “State of the Commute” report. The number of those taking public transportation to and from campus has doubled in the past decade—due in large part to a generous bus pass subsidy program that’s funded by parking and citation revenue. The university’s vanpool program is large and visible. And BruinBus, the free, cross-campus shuttle, clocked more than 1.2 million trips last year.

“I love the BruinBus,” said Scott Morrison, a senior majoring in history who lives near campus in a fraternity. “Most people I know don’t have cars.”

Certainly, cars are still a major fact of life in Westwood—with congestion levels there among the worst in the city.

That makes it all the more improbable that an institution in the eye of L.A.’s traffic storm would be able to transform itself into a laboratory for alternative transportation solutions. And those efforts, oddly enough, were inextricably linked to the university’s ambitious, and controversial, growth plans.

Between 1990 and 2011, university officials estimate that campus square footage increased by 66%—from 10.4 million square feet to 17.3 million. Although the new buildings included the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, the Anderson Graduate School of Management and the Terasaki Life Sciences Building, much of the new construction has been for student housing. So even though UCLA’s student population went from 36,427 in 1990 to 40,675 last year—an increase of less than 12%—the percentage of students living on campus rose far more dramatically, from 12% to 29%.

The university’s evolution from commuter campus into a more residential environment means that more than 29% of students now walk to school. Among them is Erika Gonzalez, a first-year biology student, who said that getting from her dorm to class is a cinch.

“I just go down a little hill and I’m there,” she said. “I just walk everywhere.”

And not having a car—it’s prohibited for dorm residents unless a student has an off-campus job or paid internship—has become business as usual.

“Cars kind of become communal things,” said Holli Herdeg, a first-year Greek and Latin student who said dorm-dwellers turn to friends who live in apartments when they need a lift off campus.

A key turning point in the university’s transportation evolution came in 1990, when then-Chancellor Charles Young agreed to something that was relatively novel at the time: city-imposed caps on the number of trips into and out of campus that, if exceeded, would bring new development to a halt.

“Chuck said, yeah, I can live with that. All of his people, their mouths dropped open,” recalled Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, who at the time was a Los Angeles City Councilman representing the area.

“For us down in the trenches, it was a little bit of a gulp,” said Renée Fortier, the executive director of UCLA Events & Transportation, who at the time was the university’s associate director of transportation services. “We agreed with the city that we would measure every single trip into and out of the campus. If we went over, all construction would stop. It wasn’t an agreement that didn’t have teeth.”

A wide-ranging building program on campus was essential, Young said at the time, to keep and expand the university’s standing as a top-tier research university.

But community groups had serious concerns.

“This idea of not producing traffic is a bad joke,” Laura Lake, then president of Friends of Westwood, said skeptically at the time.

Today, Lake sees some positive signs, including the university’s vanpool program and its efforts to house more students on campus. But she questions whether the methodology provides an altogether accurate accounting of UCLA’s overall impact on traffic because it doesn’t include off-campus university-owned buildings in Westwood. “Unless one looks at the whole enchilada, you don’t know what you have,” said Lake, currently co-president of the group Save Westwood Village.

(The university said that the vast majority of employees who work in its Wilshire Center or in leased space elsewhere in Westwood park in UCLA-owned parking facilities and are counted as part of its daily trip averages.)

Sandy Brown, president of the Holmby-Westwood Property Owners Association, added that whatever the numbers show, the experience of driving through Westwood Village is still a “disaster,” especially during afternoon rush hour.

“There’s reality, and then there are studies,” she said. “I would tell you that the studies don’t match reality.”

For his part, Young believes the university succeeded beyond expectations on two difficult fronts by expanding the square footage on campus more than it had initially envisioned and reducing traffic “even more than we thought we would.”

“We knew it wasn’t going to be easy,” he said recently, “but there were actions that we could take that would guarantee or at least make it likely” that UCLA would stay within the agreed-upon limits.

The university, limited by the city of Los Angeles to 139,500 trips to and from the campus each day, got as high as 125,792 trips in 2003 before dropping to the record low of 102,027 last year.

Although the university is no longer required to report its trip counts to the city, it has continued to do so in annual “cordon count” surveys that measure traffic into and out of the campus. While city Department of Transportation officials said they could not immediately project how bad traffic would have been in the area without the agreement, they said it was safe to assume that any trip count that falls below what was mandated in the cap represents a reduction in cars traveling on Westwood streets.

Meanwhile, those still-crowded Westside streets are providing another incentive for UCLA students and staff to get on the alternative transportation bandwagon.

“The congestion is just so bad that some people are happy to let a bus operator drive,” said David Karwaski, UCLA’s senior associate director for Planning, Policy & Traffic Systems.

That’s certainly true of Christina Trieu, a third-year student who lives off campus but walks or takes the BruinBus to get around.

“I do have a car, but I don’t want to drive here,” she said. “It’s too crazy.”

Posted 4/4/12

Westside story—always a traffic drama

October 9, 2011

It’s official: Rush hour on the Westside is nasty, brutish and long.

A new report assessing potential routes for the Westside subway extension looks at current traffic conditions in the area to project what the future would likely bring, with or without a subway.

In doing so, it quantifies some of the modern-day commuter horror stories that have become the stuff of local—and international—legend.

The report offers a snapshot of a deeply dysfunctional network of freeways and surface streets in which rush hour traffic moves at less than 10 miles per hour. A major incident can bring the entire area to a standstill. (Remember President Obama’s motorcade last month?) Rush hour starts at 6:30 a.m. and continues till 10 a.m., then picks up for the afternoon onslaught from 3 p.m. to 7 p.m. “and beyond.”

“During a typical weekday evening, an auto trip along Wilshire Boulevard from Santa Monica to Beverly Hills takes up to 60 minutes to cover a distance of only 8 miles,” according to the report. “Morning and evening peak-hour speeds along Santa Monica Boulevard in Beverly Hills average less than 7 mph.”

The report’s analysis confirms what Westside road warriors have known—or at least suspected—for years. But the document, formally known as a draft Environmental Impact Statement/Environmental Impact Report, offers a level of detail that goes beyond anecdotal complaints.

Among its key findings:

- Of all the busy intersections in the 38-square-mile area around the proposed subway routes, Wilshire Boulevard west of Veteran Avenue is by far the worst, with daily traffic averaging 122,618 vehicle trips. It is followed by Santa Monica Boulevard east of Cotner Avenue (68,277) and Sunset Boulevard east of La Cienega Boulevard (66,043.) Among north/south surface streets, the most crowded intersections are Sepulveda Boulevard at Pico Boulevard, with 59,081 daily trips, and Bundy Drive south of Pico, with 59,022.

Click here for a list of all the key intersections and their daily traffic volume.

- Freeway interchanges, not surprisingly, are even busier. The Santa Monica Freeway at Bundy Drive averages 244,000 vehicles a day; at Crenshaw, the figure is 291,000. It’s even more jammed on the 405 Freeway, where the Olympic Boulevard interchange averages 319,000 vehicles daily.

- Some 42% of intersections in the area are flunking the test for rush hour navigability. With six “level of service” grades beginning at A (flowing freely) and ending at F (unacceptably congested,) 80 of the 192 intersections studied were rated an E or F.This map shows where rush hour traffic is most jammed.

- About 50% of Metro’s entire weekday bus ridership comes from routes that go through the subway study zone. Those buses, with some 550,000 boardings each day, average only 10-15 miles per hour on Wilshire, and 10-14 mph on Santa Monica. (The addition of a dedicated bus lane on Wilshire should improve average passenger travel times by 30%, the report said.)

The report did not compare the conditions in the study area to those elsewhere in the county, although it said: “Wilshire Boulevard represents the single heaviest used transit travel corridor in Southern California.”

Tom Jenkins, a consultant who acted as project manager for the subway extension report when he was with the firm Parsons Brinckerhoff, said there are certainly trouble areas elsewhere, such as in the San Fernando Valley and on the 101 Freeway. However, he said, when the subway study area’s concentration of jobs and activity are factored in, “you’re not going to find any area in the county that’s as congested.”

The draft report marshaled the data in order to make the case for building a westward extension of the subway. The routes under consideration could extend Metro’s Purple Line to Westwood or Santa Monica, with the possible addition of Red Line stations in West Hollywood.

In addition to analyzing the current traffic picture, the report looks ahead to 2035 and predicts worsening congestion in the area because of projected population and job growth.

Metro officials say the subway would not be a “silver bullet” to assuage all of the Westside’s traffic woes.

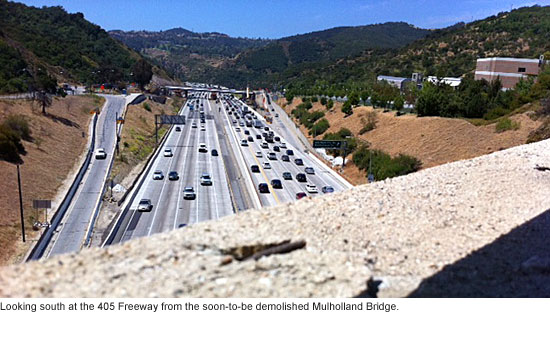

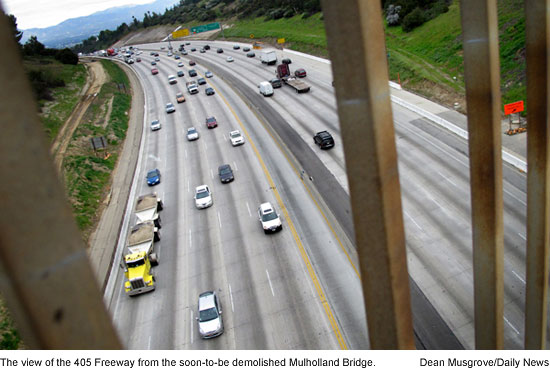

But the report noted that the area is highly urbanized and “built-out,” and has few, if any, options for adding or expanding roads. It stated that the only such project currently underway is the 405 Sepulveda Pass widening, which will add a 10-mile northbound carpool lane to the 405 as it heads away from the 10 Freeway.

“Local jurisdictions are not planning any major roadway expansion projects through 2035,” the report said, adding: “In the cities on the Westside, policy-makers have taken strong positions against the wholesale widening of streets and narrowing of sidewalks to accommodate more travel lanes.”

The subway, the report said, would offer a much-needed transportation alternative—one that is expected to be faster and more reliable than getting behind the wheel.

“The improved capacity that would result from the subway extension,” it said, “is the best solution to improve travel times and reliability and to provide a high-capacity, environmentally-sound transit alternative.”

Posted 9/09/10

Where L.A.’s lost weekend hits home

June 2, 2011

In neighborhoods all around the 405 Freeway, people are scrambling to find answers to the biggest question of the summer: To get out of town, or to hunker down?

In neighborhoods all around the 405 Freeway, people are scrambling to find answers to the biggest question of the summer: To get out of town, or to hunker down?

“I’m terrified. I have company coming from out of town. What are we going to do?” said Dr. Anne Kelly as she waited to have her hair done at a local salon this week.

“We’re going to be virtually prisoners,” said Kelly, a psychologist who’s lived in the Roscomare Valley neighborhood on the east side of the freeway for 40 years. “I understand that things have to be done, but boy oh boy.”

When it was suggested that her professional services may be in demand, she joked: “I think you’re going to need a psychiatrist to dispense medication to deal with all the road rage.”

Yes, when you close one of the world’s busiest freeways for 53 straight hours, emotions run high—and people run scared. That goes double for folks in neighborhoods near the Mulholland Bridge, which is being demolished and rebuilt to make way for a 10-mile northbound carpool lane on the 405.

After a couple of hours of prep work that starts before midnight on Friday, July 15, the entire freeway will be closed all day Saturday, July 16, and Sunday, July 17, reopening at 5 a.m. Monday, July 18. The closure will stretch north from the 10 Freeway all the way to the 101, and south from the 101 to Getty Center Drive. Even with the official mantra of “Plan Ahead, Avoid The Area, Or Stay Home,” there are concerns in the community that huge numbers of motorists will have to be diverted onto their streets, causing gridlock and placing locals under virtual house arrest.

Already, a spirit of resignation is taking hold in Roscomare Valley, on the west side of Bel-Air, as some neighbors get ready to take cocooning to a whole new level.

“As a joke, I said let’s get enough food in for the weekend and not go out. I think it’ll be awful getting out of town,” said Belinda Broughton, a violinist having lunch with her son, Oliver Britten, at the tiny Sugar Cube café.

The same goes for Paul Gamberg, who represents the Roscomare Valley as an alternate on the freeway project’s community advisory committee.

“We’re planning to be landlocked and to swim a lot. We’ll provision up. I don’t think we’ll have a hard time getting to Whole Foods, but we might,” said Gamberg, who oversees a Yahoo message group that serves as a sounding board among neighbors concerned about the project.

“I get emails all the time from people who are up in arms,” he said. “There’s been a lot of fury.”

A lot of it is apprehension about the “hellish” 53-hour freeway closure. But what really has him on edge is what happens afterward—when routes through the “desirable, paradisiacal neighborhood” become clogged and increased traffic worsens the condition of local roadways.

“We’re the first canyon east of the 405,” he said. “The reason our road is closed to through traffic is because it’s a narrow street and the city can ill afford to keep up with the potholes as it is.”

While some are getting ready to tough it out at home, others are making plans to hit the road.

“We’re getting out of here! We’re going to go camping,” said Joko Tamura, who’s also had to reschedule her son’s 11th birthday party from July 16—the actual date—to July 9. (And Tamura’s not the only one to take a red pencil to the calendar; weddings, religious services and museum exhibitions in the area also have been shuttered, moved or postponed.)

Amid all the apprehension, there are those in the neighborhood who feel that the 53-hour closure will just be one more chapter in the long and difficult saga of the $1.034 billion I-405 Sepulveda Pass widening project.

“The street is just awful. Getting to the 405 used to be 5 minutes; now it’s much longer. And Sunset is just unbearable,” said Karen Klaustermeyer, who moved to the Roscomare area in 1971. “It’s just tearing up everything. The city of L.A. should look at the deterioration…I think they’ve forgotten about us.”

For those closest to the action, the best survival strategy for getting through the weekend-long freeway closure will be acceptance—and a positive attitude, said Robert Ringler, president of the Bel-Air Beverly Crest Neighborhood Council and a chair of the LAPD’s West Bureau Traffic Committee. “Screaming and yelling is fruitless,” he said. “Attitude—it’s so important. Attitude and planning.”

Posted 6/2/11

405 reasons to plan a new July route [updated]

May 18, 2011

On July 15, moviegoers around the country will find out whether Voldemort meets his doom in a showdown with the wizarding world. But if you’re thinking of catching a midnight showing of “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2” in Westwood, better find a way to get there that doesn’t involve the 405 Freeway.

On July 15, moviegoers around the country will find out whether Voldemort meets his doom in a showdown with the wizarding world. But if you’re thinking of catching a midnight showing of “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2” in Westwood, better find a way to get there that doesn’t involve the 405 Freeway.

That same night marks the beginning of the end for the Mulholland Bridge. After two hours of prep work starting at 10 p.m. on July 15, demolition of the bridge will begin just after midnight—a maneuver that will require a weekend-long closure of one of the most heavily traveled freeways in the nation.

Moviegoers are just one L.A. interest group that will need to come up with alternate routes to navigate the 53-hour closure, which will be in effect all day Saturday, July 16, and Sunday, July 17, and will continue till 5 a.m. on Monday, July 18. At this point, plans call for closing the freeway from Getty Center Drive to the 101 Freeway, but that and other details may change depending on the outcome of meetings being held this week among Metro, the CHP and other agencies.

Updated 5/27/11: The latest plans call for the 405 Freeway to be closed northbound from the 10 Freeway to the 101. The southbound freeway will be closed from the 101 to the Getty Center Drive offramps. Full details are here.

Already, the mega-closure has event organizers and others scrambling for ways to cope. From LAX-bound travelers to beachgoers, golf lovers to museum hoppers, the closure promises to throw a big curve into that perennial L.A. question of how to get there from here.

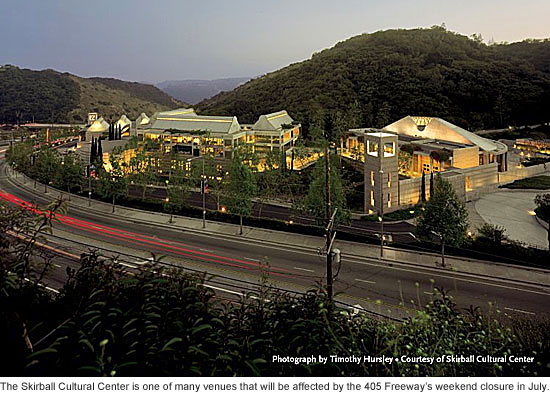

The Skirball Cultural Center has decided to close its gallery doors altogether for the weekend—which means you’ll need to pick another time to check out the center’s popular Houdini and “Masters of Illusion: Jewish Magicians of the Golden Age” exhibits.

At this point, just one private event—a wedding—is still on the books for the Skirball that weekend. The staff is “cooperating closely with the families to come up with best options for guiding guests to our site as efficiently as possible and extending welcome to them upon arrival and throughout the event,” spokeswoman Mia Cariño said in an email.

Like that intrepid wedding party, the nearby Getty Center has opted to stay the course and will remain open. The Getty expects “strong visitorship despite the freeway construction,” spokeswoman Julie Jaskol said in a statement, pointing out that, as plans stand now, the northbound Getty Center Drive ramp will be open, while visitors coming from the south will need to take Sepulveda Boulevard.

Updated 6/2/11: The Getty has since decided to close for the weekend. And that last wedding party at the Skirball? They’ve rescheduled for July15.

The Hermosa Beach Open Beach Volleyball Tournament is also scheduled for that weekend—and the freeway closure plans were not welcome news to organizer Dave Williams.

“This is the first I’m hearing of it. Yes, it will be very negative,” he said. “It’s a big event. We may have to move it.”

Further south, the Trump National Golf Course in Rancho Palos Verdes is the setting for the big Los Angeles Police Celebrity Annual Golf Tournament on Saturday, July 16—which may also require some extra planning by those traveling from the Westside or San Fernando Valley.

“We’re trying to figure out how we’re going to notify people of alternate routes,” said Alan Atkins, executive director of the Los Angeles Police Memorial Foundation, which puts on the traditionally star-studded tournament, to be hosted this year by Jerry West. “It’s going to cause a lot of headaches because probably half of them come from the Westside.”

And at UCLA, school’s not in session, but parents of students enrolled in high school summer programs on the campus that weekend are being notified of potential pick-up and drop-off challenges.

Whatever your summer plans may be, the advice from Metro, which along with Caltrans is running the 405 Sepulveda Pass Improvements Project, is to stay home that weekend if possible or become well-acquainted with the official detour maps before leaving home, since freeways and surface streets beyond the 405 may be affected.

Mike Barbour, in charge of the project for Metro, said picking the date for the weekend-long closure meant avoiding holiday weekends and times when schools were in session.

“We think this is the right date. It was sort of a light weekend, really,” Barbour said.

While the project’s other demolition work on the Sunset and Skirball bridges required a series of overnight closures of the freeway, the steepness of the Mulholland Bridge means that it will be safer for motorists if the demo work is done over one weekend, Metro officials said.

Still, the demolition of the Mulholland Bridge will be the easy part compared to the “very daunting” task of arranging and communicating the freeway closure, Barbour said.

“I would say that the technical work is not that big of a deal,” Barbour said. “But traffic management, and working with all these different agencies, and coming up with a plan to convince people to stay off the freeway—it’s very significant. It’s very challenging.”

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink