Three maps, many voices

September 7, 2011

Officially, three maps—two of which would radically reshape L.A. County’s political landscape—were at the heart of the Board of Supervisors’ public hearing on redistricting Tuesday.

But the day really belonged to the people, hundreds of them, who came to the Hall of Administration from all corners of the county to take a personal stand on what has become a highly political redistricting fight.

They packed the 690-seat board hearing room and at least 200 more crowded into two overflow rooms during the lively but generally good-tempered meeting. In all, 207 speakers, each allotted a minute to make their point, ended up addressing the Board of Supervisors during the marathon session. Their comments offered a dispatch from the front lines of governance, touching on everything from literally street-level services like traffic-slowing rumble strips on canyon roads to the very nature of representative democracy itself.

And many speakers, from many parts of the county, seemed to feel the same way as Malibu City Councilmember Lou La Monte, who told the board: “We ain’t broken. Please don’t fix us.”

“Anyone who lives here knows that the North Bay and South Bay have different interests,” La Monte said. “Maintaining as closely as possible the existing 3rd District lines would continue the success we have achieved working with our natural neighbors…Our present 3rd District works very well the way it is.”

The public hearing represented an important moment in the county’s once-a-decade redistricting process, in which the five supervisorial districts are rebalanced to reflect population changes measured by the U.S. Census. On Tuesday, many speakers favored map A3, which makes only modest changes to the current district boundaries, and opposed maps S2 and T1, which would dramatically redraw the lines and reassign more than 3 million residents in an effort to create a second supervisorial district in which Latinos make up a majority of the citizen voting age population. Both S2, submitted by Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, and T1, proposed by Supervisor Gloria Molina, would divvy up the San Fernando Valley among three supervisors, instead of the two who share it now.

“While I’m proud of my culture and my heritage, I am torn between two lovers today,” said Sylmar resident and community activist William “Blinky” Rodriguez, who said he’d decided to side with his current supervisor, Zev Yaroslavsky, in the redistricting showdown. He credited Yaroslavsky and his staff with years of commitment to the northeast San Fernando Valley, with its large Latino population, and said: “I’m here to support not breaking up the San Fernando Valley, not breaking up the 3rd District.”

Yaroslavsky, who is in his final term as a county supervisor and thus not personally affected by the proposals, has strongly objected to the S2 and T1 plans as needlessly disruptive and damaging to communities throughout the county. (Read his blog here.)

Some 3rd District residents said they fear that the sweeping redistricting proposals would sweep away years of environmental progress.

“I haven’t heard enough here today about the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area,” said one speaker, Bruce Benson. “It’s the largest urban national park in America. T1 and S2 will slice and dice this national treasure. Without A3, the wealthiest and most influential among us will move in to develop the mountains. Without A3, the bulldozers are on their way.”

Supervisor Don Knabe, who is up for re-election next year in a district that would be profoundly transformed under either the S2 or T1 plan, came in for vocal praise from many of his constituents, who turned out to support his A3 plan and advocate for keeping the 4th District largely intact.

“He is our hero,” said one speaker, Robert Thome of Whittier, a patient at Rancho Los Amigos Hospital in Downey.

Some who showed up to support Knabe’s A3 plan wore black T-shirts from the Energy Pathway Program at the South Bay Center for Counseling. Others, from communities linked by the Santa Monica Mountains, wore green ribbons. Both factions stood and waved together when their favored plan was mentioned.

On the other side of the issue, supporters raised signs reading “Follow the numbers…Follow the law!” when speakers advocated the S2 and T1 plans. Some also praised Molina as a trailblazer whose presence on the board grew out of a redistricting battle two decades ago.

“Twenty years ago, it took a court case to create the district that we now have [represented by Supervisor] Gloria Molina,” said Andre Quintero, mayor of El Monte. “This is one of those last legacy issues where you can create a district that not only gives Latinos an opportunity for another position here on the Board of Supervisors, but will create a huge impact for the county.”

“I urge you not to turn back the clock. Support two Latino districts,” added Jesus Andrade, of the National Council of La Raza.

Latinos make up 48% of the county’s overall population, and about one-third of its citizen voting age population. The federal Voting Rights Act requires equal opportunity for minority groups. However, courts have ruled that “50% districts”—those in which one minority group makes up more than 50% of the voting age citizenry—are required only when voting is so racially polarized that non-minorities vote against minority-preferred candidates so consistently that those candidates are denied an opportunity to win.

One speaker, George Brown, a Gibson Dunn attorney who served as voting counsel to the statewide Citizens’ Redistricting Commission, told the board that studies have found evidence of “racially polarized voting” among Latino and non-Latino voters in Los Angeles County.

But others argued that county voters have demonstrated they will vote for Latino and other minority candidates without the need for such dramatic boundary changes.

“To say that we need more Latino elected officials in our area is ridiculous,” said Alina Mendizabal, a community activist in Sylmar.

“Please. You don’t know our neighborhood. If you knew the San Fernando Valley, you’d know we already have tons of [Latino] elected officials.”

“We already have equality in our county,” added Mario Guerra, a city council member in Downey. “I’m insulted that anyone would suggest that in our particular city that we vote by the color of the skin or somebody’s surname…Let’s not move 3 million people around. Representation, not race.”

Other speakers expressed concerns that the Asian-Pacific Islander community would lose out under S2 and T1. “As we all know, L.A. County is one of the most culturally diverse places in the world, and the current 4th District boundary is well-balanced with diverse people from the white, Latino, African America, Asian American and other minority groups,” said Kimthai Kuoch of the Cambodian Association of America. ”Under plan S2 and T1, millions of people will be shifting and it will dilute our voting voice to almost nonexistent.”

Beyond questions of race and representation, the afternoon-into-evening session also offered a vivid look at how geography can be destiny—for better or worse.

People from communities in and around the Santa Monica Mountains, for example, worried that proposed boundary changes could have a negative effect on everything from land use to water quality to emergency preparedness.

And some feared the loss of long-running alliances.

“The city of Santa Monica currently has a number of regional issues, including homelessness, the environment, transportation, all of which are being addressed on a regional basis through our long-standing ability to work with our neighbors,” said Gleam Davis, mayor pro tem of Santa Monica, who said she was speaking as an individual citizen. “If our neighbors become very distant, such as in Long Beach, it will be much more difficult to find that community of interest and more difficult for us to meet the needs of our own constituents.”

Davis, a former trial attorney in the Justice Department’s Civil Rights division, said she believes the board “can meet both the letter and spirit of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act by still maintaining the communities of interest that have been developed over the past few decades. It would be a shame to unravel the very important and powerful relationships that we have formed over the past decades by changing so many people and moving them around.”

The Board of Supervisors will hear a final round of public comments on the redistricting proposals on Sept. 27 and are expected to take a vote that day. If supervisors can’t pass one of the plans with a 4-1 margin, a special redistricting commission made up of District Attorney Steve Cooley, Sheriff Lee Baca and Assessor John Noguez will choose a plan.

Posted 9/7/11

Road warriors get ready to rumble

February 1, 2011

The switchbacks and hairpins of the Santa Monica Mountains have lured thrill seekers for generations. But starting this spring, Los Angeles County will be throwing speed demons a new kind of curve.

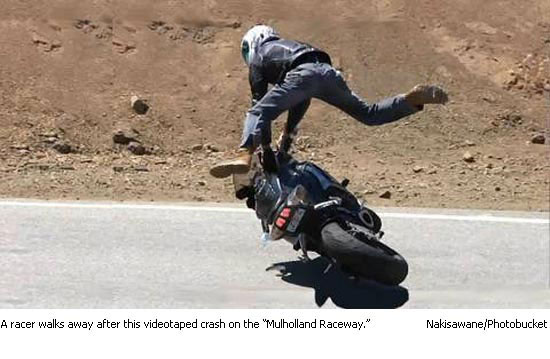

After years of study and preparation, the Department of Public Works will soon be installing speed-deterring “rumble strips” down the center lines of one of the most popular and storied amateur racing loops in Southern California: the section of the so-called “Mulholland Raceway” that starts and ends at Mulholland Highway and traverses Stunt, Schueren, Piuma and Cold Canyon roads.

The move comes at the behest of local homeowners, who for years have sought relief from the rip and roar of the high-performance sports cars and motorcycles that race through the canyons day and night. Over the years, authorities have tried various solutions, from increased traffic patrols to seizing the vehicles of illegal street racers, but the practice has persisted.

California Highway Patrol Officer Leland Tang says the patrol area around the Stunt-Piuma loop has averaged nearly 40 traffic collisions a year for the last several years. The collision average has been about 50% higher on the west side of Las Virgenes, Tang says, but the outcry on the east side has been more concentrated because that area is more densely populated. (Click here for a map of the loop.)

“It’s scary just to go to your mailbox,” says Mary Ellen Strote, who has lived near the top of Stunt Road since 1981.

Some are just Sunday drivers and law-abiding enthusiasts, she and other homeowners say, but too many others are revved-up young men testing their machines and their mettle.

“The tailgating, the passing on blind curves, the aggression,” Strote says. “You’ll be driving along, and there’ll be a bicyclist on one side and a motorcyclist in the other lane and then here will come some insane person, passing on a blind curve.”

Those curves—blind and otherwise—are the targets of the rumble strip project, says Todd Liming, senior civil engineering assistant at the county Department of Public Works.

During the past decade, residents have complained that street racing in the area has become an increasing danger, as drivers and motorcyclists—especially the inexperienced ones—have sought to shave seconds by cutting corners and darting across the center line in and out of oncoming traffic. Some race in packs, warning each other of law enforcement via text message and cell phone. Some yearn to emulate professional test drivers.

Strote and others say Stunt Road has become particularly popular because outsiders think—incorrectly—that it was named for Hollywood stunt drivers. (In fact, the road was named for the Stunt family, homesteading fruit-growers whose nearby ranch is now part of the University of California Natural Reserve System.) Over time, pressure has grown to find fresh solutions to the ongoing concern.

Initially, Liming said, area residents urged speed humps as a way to discourage racing, but humps posed too big a safety risk on the hilly and winding roadways. Improved signage helped, as did stricter enforcement, which was ramped up over the years as part of Operation Safe Canyons, a state and local task force led by Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s office.

But traffic mitigation is particularly difficult in mountain areas, says Liming. And patrols can only do so much in an area as vast as the Santa Monica Mountains, Tang adds. Finally, after several years of study, county engineers came up with centerline rumble strips – sections of small grooves cut directly into the asphalt – as a possible way to deter corner-cutting, drifting and other dangerous aspects of what amateur racers call “canyon carving.”

The indentations, which are 5 inches wide and a little less than a half-inch deep, literally and figuratively underscore the double yellow line that separates lanes of opposing traffic.

Used for years along the sides of highways elsewhere to warn drowsy motorists that their cars might be straying onto the shoulder, rumble strips along the center line offer a similar warning to cars and especially motorcyclists who stray toward the middle of the road, rather than its edges, Liming says. The strips create an intense, unpleasant vibration when tires hit them and alter the road surface just enough to force cyclists to slow down in the event they decide to cross them—especially at high speeds and at an angle.

The solution is not without its own possible downsides. Although centerline rumble strips have been used successfully in other areas—the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, for example, credited them last year with a 35%-50% reduction in crashes in areas on which they were installed—any change in the road surface can create hazards, especially for bicyclists and motorcyclists.

And homeowners may be trading one form of noise pollution for another: When tires hit the strips, however they’re positioned, it’s loud.

“This is a pilot project,” says Liming, who stresses that county engineers will be closely monitoring the effort. If the strips work, he says, they will eventually bisect the entirety of the 14.5-mile loop except for a short section on Mulholland Highway. This might lead to their use in other race-plagued roads in the area. The project is expected to cost $425,000 to $475,000, though federal grants are covering most of that price tag. The initial phase, put out to bid late last year, is expected to start in April.

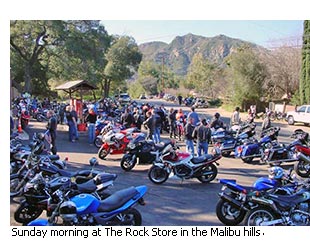

The plan drew mixed reviews on a recent day at The Rock Store, the popular Mulholland Highway restaurant and biker hangout.

“What?! No way!” exclaimed veteran motorcyclist Scott Storey, a 53-year-old Canadian who says he’s been riding since the age of 15 and is still recovering from a fall on a blind curve that wrecked his Ducati in July. Storey expressed concern that rumble strips anywhere on the road might pose an accident risk to an inexperienced rider. He says that once a motorcycle loses traction, especially while leaning into a curve, only the most skilled can keep from crashing.

Pulling a camera from his pack, Storey shared some videos he’d just taken of rides along Stunt and Piuma, using a lens strapped to his chest. They provide a rider’s-eye view of the curving roadway and sheer cliffs along the loop, and illustrate the difficulty of negotiating these roads quickly.

“I figure if you can’t stay on your side of the road, you can’t drive very well,” says Storey. “I figure its best to live to ride another day. But some people, their idea is to get down the road as fast as possible to feel like a big man. And the fastest route is to ignore the double yellow lines.”

“It’s not gonna stop ‘em,” agreed Malibu photographer Paul Herold. “It’ll discourage the bikes, but the bikes aren’t crossing the double yellow anyway—anybody on two wheels up here will tell you that the first rule of canyon riding is to never cross the double yellow. The cars, though—the cars aren’t gonna slow down.”

Other enthusiasts, however, thought rumble strips might be worth trying.

“I used to live off Latigo Canyon in the 1970s, and there would be nobody when we’d ride, but it’s too congested now,” says Kaming Ko, a 56-year-old former motorcycle and auto racer who lives in Woodland Hills.

“You can’t change what people do, but you can discourage them from doing something stupid. They’re still going to go fast, but maybe this will help them maintain some integrity and get them to stay in their own lane.”

Posted 2/1/11

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink