Benched Lakers star still on a mission

May 8, 2012

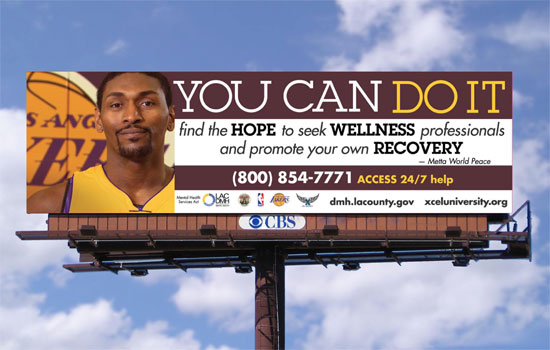

Billboards like this represent the continuing collaboration between Metta World Peace and Los Angeles County.

“I was 110 percent wrong,” the suspended Laker says of decking an opposing player with a nasty elbow to the head. “People can say what they want. I’m not going to get down on myself because I made a mistake. I’m not perfect. But it’s not going to stop me from talking about mental health.”

And the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health suddenly has a teachable moment on its hands.

For more than a year, the player formerly known as Ron Artest has been in a very public partnership with the mental health department, appearing at high school assemblies and in public service announcements to encourage young people to be unafraid of seeking psychological treatment. Dozens of billboards and transit ads with World Peace’s picture, along with the NBA logo and the L.A. County seal, carry the catchphrase: “You can do it.”

The campaign was, in a sense, testimony to the public rehabilitation and redemption of Artest, who was famously suspended for 86 games for brawling with fans in the Detroit Piston’s arena in 2004 when he played for the Indiana Pacers. Last year, World Peace—who credits a team of therapists for helping him with everything from parenting skills to anger management—was honored with the NBA’s good citizenship award.

But on Sunday, April 22, that goodwill vanished the moment James Harden of the Oklahoma City Thunder crumpled to the hardwood of Staples Center. World Peace had been pounding his chest after a dunk when he let loose with a powerful round-house elbow behind the left ear of Harden, who’d come face-to face with the pumped-up Lakers forward.

The fallout was swift. World Peace, suspended for 7 games, was widely criticized on TV, talk radio and internet postings as a thug who’d lost the right to be called World Peace, a fraud who preached mental health but who indulged his demons. He was, they said, back to being Ron Artest.In an a column for ESPN.com, former Lakers’ great Kareem Abdul-Jabbar put it like this: “In returning to his old ways, Metta has wasted all the goodwill, including the J. Walter Kennedy Citizenship Award, he earned when he was on his best behavior.” A sports columnist for the Orange County Register, Jeff Miller, was equally harsh, saying that World Peace had “tainted all the good things he has achieved in promoting mental health.”

But inside the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health, the view was decidedly more nuanced. Experts there emphasized that mental health recovery is a process often accompanied by relapse.

“When I saw what happened in the game, I thought, man, the adrenaline just got out of control,” said Dr. Marvin Southard, the department’s director. “It was an ugly event but it seemed to me that it was not purposeful, rather an artifact of the emotion of the moment.”

For all of us, Southard said, “our aspirations and desires to do the right thing don’t always live up 100 percent to our actions…It doesn’t happen all at once. The goal is for the actual self to get closer to the ideal self day by day.”

As for the agency’s partnership with World Peace, Southard said: “I don’t feel embarrassed that the department is connected to someone who makes a mistake. I don’t know who hasn’t made one.”

For his part, World Peace said in an interview with Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s website that the incident occurred simply because he got “over excited” after slamming down several dunks that reminded him of his performance as a younger player.

“I never thought I could reach that plateau again,” he said, adding: “It was pure excitement.”

World Peace said that, with his much improved game, he’s now working “all the time” with his therapist to keep from getting overtaken by emotion, as he did last month and in his earlier years. “She’s trying to show me how to play with less passion and still be effective.”

And that’s no easy lesson, he said, because this is “no kids’ game. I know people who throw more elbows than me. It doesn’t feel like a game to us. It feels like life or death.”

As he tries to reconcile the disconnect between his public image and his public mission, he can’t help feeling that he’s being judged more harshly than he should be in the situation.

“The only issue I have is people trying to single me out, trying to tarnish what I’m trying to do in the community. They try to destroy everything I’m working for.”

And those things, he said, “are bigger than basketball.”

Posted 5/8/12

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink