Ex-military nurse now fights for vets

January 31, 2013

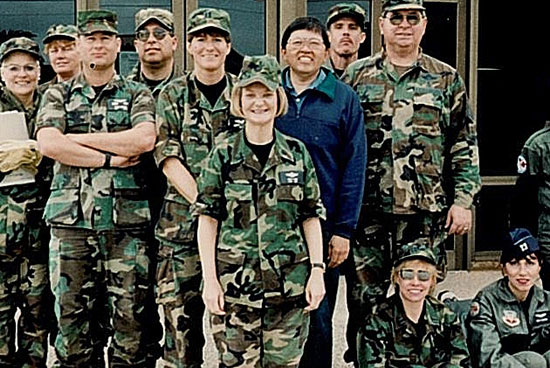

Ruth Wong, center, leading a military exercise at Camp Pendleton in 1990, a year before Operation Desert Storm.

Even as a little girl, Ruth Wong aspired to the Right Stuff.

“I knew at 8 years old that I wanted to be a nurse, and I was probably 12 when I started thinking about the military,” she remembers.

By the age of 20, she was in the U.S. Air Force, studying to become a flight nurse. By 40, she was in the Persian Gulf, commanding 50 medical personnel, sleeping in a chemical suit and packing a 9-millimeter sidearm.

By the time she retired from the service in 2001 and went to work for Los Angeles County, she was a Brigadier General.

So last week, as U.S. Defense Secretary Leon Panetta lifted the ban on women in combat, Wong—who last month became the first woman to head the Los Angeles County Department of Military and Veteran’s Affairs—cheered it as a step in the right direction for the institution that had helped her realize her heart’s desires.

“They’ll have to be physically able, emotionally strong, and be able to fight shoulder-to-shoulder with their male counterparts,” she says. “But this is going to afford an opportunity for women to advance in career fields they may have dreamed about for a very long time.”

Wong, who moved to the military and veterans affairs department in August after nearly a decade as executive director of the county’s Quality and Productivity Commission, says she sometimes thinks that her whole life has been leading her toward her current job.

“When I came here, I was told it would be a temporary assignment,” says Wong, who became acting director after the retirement of Col. Joseph N. Smith in December. “But after a couple of months, I began to think, ‘This is where I belong.’”

The department, which helps L.A. County veterans access housing, education, mental health care and other services, offers a front-line view of the military’s evolution and of veterans’ evolving needs. A 2010 study by the Economic Round Table counted 328,000 veterans in Los Angeles County, including some 36,000 who had served since 9/11. That total, Wong says, has since grown to an estimated 400,000, and is projected to grow further by 2017 as forces in Afghanistan and Iraq complete planned drawdowns.

“About a third of the young people coming back from Iraq and Afghanistan are suffering from post-traumatic stress or some other mental health issue,” Wong says. “Those who aren’t suffering from post-traumatic stress are having to adapt to a new environment.”

And, Wong says, the new veterans are twice as likely to be female; 13% of veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan are women, compared to 6% of veterans overall, according to the Economic Round Table. The ban on women in combat notwithstanding, she says, the female veterans now have seen more action than at any time in U.S. history, and are coming home with not only that trauma, but with a whole set of needs specific to women.

“Some are coming back as primary caretakers to families and children, or maybe to a husband they have to bond with again,” she says. “We are seeing women who, unfortunately, are getting divorced, with young children, and have no job and don’t know where to go.”

Wong understands these struggles, both as a married woman and as a veteran who has watched the military evolve since the early 1970s. When she WAS commissioned as an Air Force officer, fresh out of nursing school in Chicago, the Vietnam War and the draft were winding down and the Equal Rights Amendment was being debated. Women made up less than 2% of the armed forces and were barred from two-thirds of the military job specialties.

“I wasn’t a feminist,” she says, recalling that her main motivation had been to travel without having to postpone her career in nursing. In fact, when her World War II-veteran father feared aloud for her safety, “my response was, ‘I’m going to be a nurse in a hospital—I probably won’t even carry a gun.’”

She met her husband, a Pasadena physician, while they were both stationed at a New Mexico air base. She served at Point Hueneme while he built a Southern California practice. Then, in 1991, war struck. Wong was promoted to flight commander of Aeromedical Evacuation Operations at the Sharjah Air Base in the United Arab Emirates. Though Operations Desert Storm and Desert Shield never brought her directly into combat, she says, she was responsible for scores of subordinates and there were frequent threats of chemical attack from SCUD missiles.

The experience shaped her in ways she recognizes in the veterans she serves now.

“I was stronger when I came back,” she says. “Just being in a country that was so different, in a wartime scenario, working with people I’d never worked with before—just being able to survive all that gave me a feeling of, ‘I can do almost anything. I’m a little bit more of a superwoman than I thought I was.”

It also sensitized her to veterans’ struggles. “They’ve faced so many things that others haven’t had to experience or face,” she says. “Things in their hometowns are different. They’re different. When I came back from the Persian Gulf, I was different.”

And, she says, so were her loved ones. “My husband is a jovial person, and when I came back, people told me over and over, ‘Your husband didn’t smile the whole time you were gone.’”

The 6-month deployment moved Wong up the ladder; her final decade in the military was spent directing and administering nursing services for the Air Force at Andrews AFB and in the Surgeon General’s Office in Washington, D.C.

She retired just before 9/11 and returned fulltime to Pasadena, where she and her husband had based their temporarily bicoastal marriage. Then the military changed her life again.

This time, it was a phone call from an old Air Force buddy, wondering if she would be interested in an opening at Los Angeles County, where the friend now worked. Soon, Wong, who had spent six years consulting with nurses to make Air Force field units more efficient, was evaluating efficiency at the county Department of Mental Health.

That gig led to the job as executive director at the Quality and Productivity Commission, and, in turn, to her current job—proving, she says, that with or without combat experience, military service can be valuable in the civilian workplace.

As can Air Force buddies. “As they say, 66% percent of all jobs are gotten through networking,” she says with a laugh.

Posted 1/31/13

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink