Assessing the tragedy

January 18, 2011

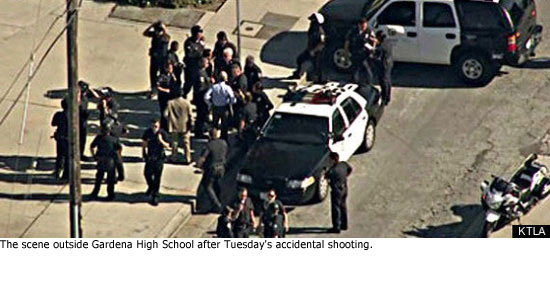

The 911 calls flew from the terrified crowds to the police dispatchers and, within minutes, to the desk of Tony Beliz: Shots fired at Gardena High School. Students wounded.

As tragedy swept through yet another campus on Tuesday morning, Beliz—deputy director of the Department of Mental Health’s emergency outreach bureau and part of an elite cadre of county mental health and law enforcement experts—rolled out to confront the questions that in the past three years have become a specialty for the School Threat Assessment Response Team.

What causes school shootings? Can they be prevented? And what is the best, and safest way to handle the aftermath?

Launched in the aftermath of the Virginia Tech massacre that left 32 dead in 2007, the county’s so-called “START” program helps schools cope with—and — and head off– such catastrophes. The first comprehensive program of its kind in the nation, START brings schools, mental health professionals and law enforcement together to prevent and deal with campus violence.

In situations like Gardena’s—in which a gun in the backpack of a reportedly frightened teenager apparently accidently fired, wounding two students with a single bullet—Beliz says he and his colleagues will make themselves available for after-the-fact mental health counseling and other support to the students and school, should it be needed. In other situations, the teams intervene early to evaluate the public threat of students exhibiting mental health problems.

START’s mission—and that of threat assessment teams like it on campuses all over the country—has been especially relevant in the wake of high profile incidents both nationally and locally.

In Arizona, a threat assessment team at Pima Community College identified Jared Lee Loughner as a potential concern months before the gunman killed six people and injured 13 in Tucson, but the larger community response was too fragmented to stop him.

Closer to home, at Cal State Northridge, school mental health counselors and campus police worked together last week to hospitalize and arrest a 22-year-old student who had not only allegedly threatened students and staff, but also had hidden firearms and explosives in his dorm room.

CSUN Police Chief Anne Glavin established the department’s threat assessment program after her arrival in 2002. Still, the department turned to county mental health officials for help at one point in ensuring that all the doctors involved understood the gravity of the student’s behavior. The student, who has pleaded not guilty, is being held on $1 million bail.

On Tuesday, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted to develop a plan to expand programs like START as a way to better identify students with mental health problems that might threaten public safety.

“Timely intervention has likely prevented a number of school tragedies,” said Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, who introduced the motion asking the Department of Mental Health and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department to explore ways to expand school violence prevention services.

“The continued presence of conditions that contribute to the frequency and severity of school-based threats make the need for an ongoing and expanded comprehensive prevention and intervention program readily apparent,” Yaroslavsky said.

Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas agreed, citing the Gardena incident.

“This kind of shocking occurrence proves that we must do everything in our power to eradicate the roots and causes of violence on our campuses,” he said.

Since its inception, START has responded to some 250 incidents of potential violence at elementary, middle school, high school and college campuses. START teams average about 200 student referrals a month, Beliz says.

The staff, comprising about 120 county clinicians and 80 law enforcement officers in Los Angeles city and county, Long Beach, Santa Monica and Pasadena, has worked closely with a variety of school districts and local universities, although the bulk of its work has been with the Los Angeles Unified School District and Los Angeles County Office of Education.

Not every school takes advantage of the program, but when they do, START makes a difference.

“There was a college student last year who had decided to stop taking his meds and was contemplating hurting himself and other people,” Beliz remembers. “And recently a 7 year old boy came to our attention, a really disturbed little boy who is fascinated by killing animals. We just saw a 13-year-old who had somehow tasted the blood of dead animals and was fascinated with violence.”

Protecting the safety of students can sometimes be tricky, requiring an understanding of possible motivations behind the potential violence, Beliz says.

“Often the schools want to expel the kid who’s made the threats,” Beliz says. “Well, think. Because with some kids, that’s the final justification. So we remind schools that every action triggers a reaction, and help them develop appropriate plans beyond zero tolerance.”

And, he says, START helps all the disparate agencies and helping hands of Greater Los Angeles find and interact with each other—no small feat in this massive metropolis.

“We try and make sure all the dots are connected,” Beliz says.

Posted 1/18/11

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink