Fighting fire with some super friends

September 25, 2011

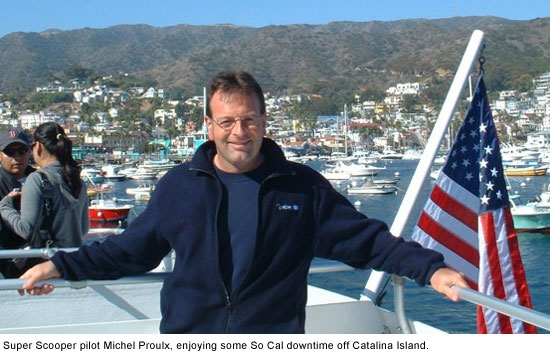

Michel Proulx has spent so many autumns in Los Angeles that he’s now a regular at pickup hockey games in the San Fernando Valley. Stéphane Monette has used his off-hours to teach himself to speak Spanish and to surf. One year, it was so dry for so long that Christmas came and went before Carl Villeneuve could return to his wife and three children near Quebec City.

Michel Proulx has spent so many autumns in Los Angeles that he’s now a regular at pickup hockey games in the San Fernando Valley. Stéphane Monette has used his off-hours to teach himself to speak Spanish and to surf. One year, it was so dry for so long that Christmas came and went before Carl Villeneuve could return to his wife and three children near Quebec City.

“It was OK,” he recalls with a laugh in his French-accented English. “You do not have snow in Los Angeles, but you have a lot of the winter decoration. One time in each four or five years, it is not so bad.”

For the past 18 years, an elite band of French-Canadian pilots and mechanics has left the Quebec backcountry to spend their autumns—and occasionally their winters—fighting fires in Los Angeles.

Fresh from their own wildfire season, they board two Bombardier CL-415 Super Scoopers leased from the government of Quebec by Los Angeles County. In the bright fixed-wing aircraft, which fly much lower and slower than commercial jet planes, they make the long trip south and west to the land of sunshine, celebrities and Santa Anas.

Once here, they check into the Burbank Holiday Inn—”our Hollywood house,” as Proulx jokingly calls it. Some meet wives and children. Some unpack sports equipment. Some pull out fiddles and guitars and hold Acadian jam sessions in their hotel rooms.

Then they get down to some of the most dangerous work on either side of the nation’s northern border.

“It’s really a unique situation, ” says Battalion Chief Anthony Marrone, who for the past seven years has acted as the Los Angeles County Fire Department’s liaison with the fliers from Canada’s Service Aérien Gouvernemental.

“They come here to risk their lives for people they don’t know, for a place that isn’t their country, for a job in which they’re not making a ton of money. But over the years, they’ve really become a part of our firefighting family.”

The famed Super Scoopers, which over the years have become a red-and-yellow icon of Southern California’s fire season, skim water from local lakes and the ocean and airdrop it onto wildfires. Los Angeles County has leased two of the sturdy aircraft during fire season annually since 1994, a year after the Old Topanga Fire killed three people and destroyed hundreds of homes in Topanga, Malibu and Calabasas. Each plane can pull in 1,620 gallons in 12 seconds, dump it and circle back at more than 170 miles an hour.

Marrone says the Super Scoopers cost the county about $2.75 million each fire season, which typically runs for 90 to 120 days, from September into December.

That price includes the pilots and their support crews, who work in 11-man rotations—four captains, four copilots and three mechanics. Each group stays for about a month, working out of the county’s air tanker base at the Van Nuys Airport, before a new group arrives via commercial airlines.

Over the years, the crews have been summoned to nearly every major fire in the county, particularly since the devastating 2009 Station Fire, when the U.S. Forest Service, which was managing the blaze, was criticized for not deploying more air power. The fire, the largest in county history, claimed the lives of two Los Angeles County firefighters while burning more than 160,000 acres and destroying some 200 homes and other buildings.

Since their arrival September 1, the planes and their crews have helped extinguish blazes in Newhall, Agua Dulce and Mandeville Canyon, among other hotspots.

“They’ve been there in Malibu, in the Buckweed Fire in Santa Clarita, in La Cañada Flintridge, in Diamond Bar and Palos Verdes, in Calabasas—everywhere,” says Marrone. “I was the helicopter coordinator on the Marek Fire in 2008 and they were out there long after any other air tanker would have had to turn back.”

The pilots downplay the danger.

“Sometimes we get bounced around when the Santa Ana winds pick up and we’re in the canyons, but mostly it is business as usual,” says Proulx, 46, who has been coming to L.A. since 2001. “We fly an aircraft that performs well in that kind of situation. When you’re using the right tool, it’s like driving a rig—it’s just a job.”

“We manage the risk carefully,” agrees chief pilot Villeneuve, who spent 11 years as a Canadian bush pilot before signing on with the Service Aérien Gouvernemental 15 years ago.

The biggest challenge, they say, is to keep track of all the moving parts of an urban fire scene. The wilderness of Quebec has its pitfalls, but news choppers and power lines and dolphins leaping in and out of the waves don’t tend to be among them. Nor do subdivisions and milling crowds.

The biggest challenge, they say, is to keep track of all the moving parts of an urban fire scene. The wilderness of Quebec has its pitfalls, but news choppers and power lines and dolphins leaping in and out of the waves don’t tend to be among them. Nor do subdivisions and milling crowds.

In Canada, Proulx says, their work mostly involves dipping into remote lakes to put out forest fires. But L.A. “looks like Legoland from the sky—I don’t know the English word for it, but the city goes on and on forever and ever. When we drop the water, we’re about 75 to 100 feet above the ground and we can see the people waving and all that. Sometimes we can see the firefighters’ faces down there.”

In fact, Monette says, one of his most vivid experiences here was in 1999 during his first L.A. fire season, when he looked down from the cockpit and realized for the first time just how high the human stakes would be on this job.

“The fires were so close to the people and the cities—it made me feel that to miss just one drop would be awful,” remembers the veteran pilot. Now 46 and the father of two teenagers in Quebec City, Monette has volunteered for the Los Angeles County contract at least a dozen times since that initial flight.

For the Canadians, the L.A. rotation is more than just a chance to hone their job skills. It’s also an opportunity to create a traveling hybrid of north-south culture. Some, like avionics technician Jean Larocque, go mountain climbing in their off hours. Eric Tremblay, 45 and on his first stint here, went to Lake Arrowhead during some time off last weekend. Jean-David St.-Laurent, a 37-year-old serving his second year in L.A., says he has taken to starting each day with a brisk 2-hour hike through the chaparral in Wildwood Canyon Park, near the hotel.

Monette is drawn to the beaches when he manages to get a day off; over the years, he says, he has acquired two surfboards. He also has worked on his communication skills. “I was surprised when I came here that everything was more or less in Spanish, not English, so I learned the language,” he recalls.

Coming to California, he says, “was a dream, since I was a little boy—this place is so associated with freedom, the California way of life.” The reality is, of course, more complex, he has since decided. “How free are you, really,” he asks, “when your way of living turns out to be an eternal rush hour?”

Proulx, whose rotation starts in October, plans to find an amateur hockey game as soon as he gets here, a habit he developed after he hooked up with an organization for Quebec expatriates online. “This year, I’m thinking about Burbank—I’ve already played in Simi Valley and Van Nuys.”

And, he adds, he’ll be bringing his fiddle.

“Another guy brings his guitar, and sometimes in the evenings, we have a few beers and play music until the bursar from the hotel comes and tells us to lower the noise.

“We play funny songs, dirty songs…My favorite one is called in English, ‘You’ve Broken the Chain on my Tractor.’ Hey, you got to do something besides just wait for fires.”

But the best part of coming to L.A., they say, is the chance to be of assistance.

Each year, they are touched by the grateful fan mail they receive. Once, they were feted by Topanga homeowners; another time, a classroom of schoolchildren drew them a packet of pictures.

And the Canadians have a secret: L.A. brushfires die more readily than Quebec’s tree-fueled conflagrations, especially with fire operations as well-run as those here.

“In Canada, we can be working on a fire for days and days and you can almost never see the end of it,” Proulx says. “But in L.A., you take off and see that big smoke, and every time, we know we’re going to go work hard and fight hard, but we got a good chance to win.”

Posted 9/14/11

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink