Unlikely duo writes new script for inmates

December 28, 2009

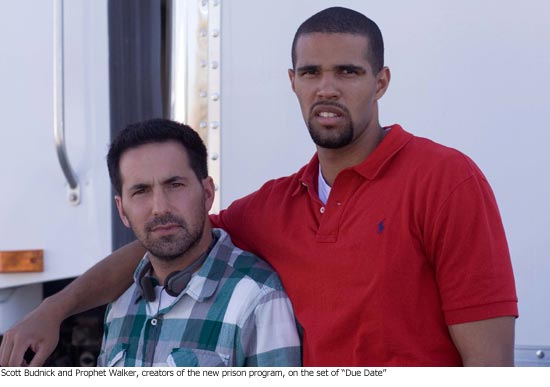

As a Hollywood executive, Scott Budnick produces buddy movies with a twist, like “The Hangover,” this summer’s gross-out comedy about the aftermath of a lunatic Vegas bachelor party, which has been nominated for a Golden Globe.

But he’s also starring, albeit far more quietly, in a real-life buddy production.

The high-energy film executive teamed up with a young prison inmate to create a new state program that gives an educational boost to L.A. County juvenile inmates who, at age 18, are facing time in California’s tough adult prisons. Launched last year, the Youthful Offender Pilot Program so far has placed about 50 juvenile offenders in safer settings with better educational and job training programs.

“I love a challenge,” says Budnick, 32. “This is a population that no one really cares about. These guys are demonized, and some people think they can’t be rehabilitated. It’s not true.”

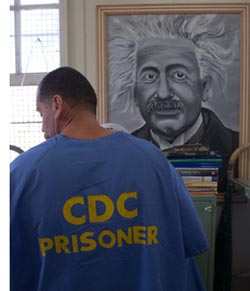

A good number of these young inmates—eight of them—are at the medium security California Rehabilitation Center in Norco, near Riverside, living in a “college dorm” decorated with murals of Albert Einstein and astronaut Neil Armstrong and featuring quiet study rooms.

There, these young charges of the penal system, along with nearly 100 older inmates, have been allowed to participate in an already existing, federally-funded college program for inmates under the age of 35. They take correspondence courses ranging from art to pre-calculus and watch DVD lectures on four new flat screens.

From Budnick, they’ve learned lessons of another sort.

“He don’t have to do none of this for us,” says Michael Tavarez, 18, from La Puente, who arrived at Norco this spring after a conviction for assault with a deadly weapon. “He has his own life, but he’s doing all this just to help us out.”

The idea for the program actually started with an inmate named Prophet Walker, who was sentenced to six years for assault with great bodily harm. He had been one of Budnick’s students in a writing program at Juvenile Hall in Sylmar, where he earned a high school degree.

At 18, Walker was shipped to an adult facility in Blythe, a rough setting for a young guy determined to right his life. Despite the environment, Walker continued to pursue his education and steered clear of the gangs that ruled the roost. After two years of lobbying prison officials, he won a bed in the lower-security Norco and a seat in its coveted educational program.

Given his own experiences, Walker figured there must be some way for other juveniles who’d done well during their incarceration to sidestep the more dangerous adult prisons, which he believed were undermining rehabilitation.

So, in 2008, he turned to Budnick for help. And the executive turned the challenge back on Walker, telling the inmate that, if he came up with a good plan, he’d sell it to prison higher-ups. In fact, Walker came up with a very good plan.

He proposed revamping the scoring system that state correctional officials use to place new inmates in prisons so that it rewarded juveniles who behaved well during their incarceration. Budnick jumped on the idea. A week later he arranged a meeting in Sacramento with Scott Kernan, who oversees inmate classifications for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation as undersecretary for operations.

Kernan was quickly receptive. He shared concerns that younger inmates can get “thrown to the wolves” in tougher, high-security facilities, making rehabilitation even more remote. “We hope this will help avert some of those problems,” Kernan says.

If an inmate and an outsider teaming up for prison reform wasn’t enough of a Hollywood ending, Walker, now 22, earned parole in November after completing an associate’s degree behind Norco’s walls. In January, he’s scheduled to start classes at Loyola Marymount University as an undergraduate engineering student.

“It’s amazing,” Walker says of his accomplishments. “I’m still coming down from the high.”

As for Budnick, he says he’s driven to help the young inmates because most people see them as a “disposable population” best locked up and forgotten.

Budnick, who grew up in a nice Atlanta neighborhood and says he never got in trouble, believes that kids in tougher neighborhoods are afflicted by the same lack of awareness of consequences as teens in more affluent areas. The difference, he says, is that guns are more pervasive in some neighborhoods. “If you grow up like me in the suburbs, the kids get in a fight and it’s not a big deal,” he says. “Here, everyone’s armed, and it takes it to a different level.”

Budnick is president of Green Hat Films, the production company of director Todd Phillips. Besides “The Hangover,” Budnick also has producer credits for “Starsky and Hutch” and “School for Scoundrels.” He’s an executive producer of another upcoming Phillips buddy film, “Due Date” with Robert Downey Jr., which was shooting this fall.

One morning in November, Budnick played hooky from filming at the Ontario Airport to visit his friends at the college classroom at Norco, the sprawling prison that houses 4,680 inmates.

“Molina, you keeping up with your work?” he asks Luis Molina, 20, from Van Nuys. Molina arrived in March, after time at Folsom State Prison for attempted murder and robbery.

“Alfaro!” Budnick greets Anthony Alfaro, 23, from Santa Monica, who entered the program last year and says he is “halfway to an associate’s degree.” Convicted of attempted murder as a teen, he’s now planning on enrolling in college after parole in two years and hopes to get an MBA someday. “I’ve got a lot of ambition,” he says.

Like Walker, Alfaro entered the state prison under the old rules, and was assigned to Centinela State Prison in Imperial County. And, like Walker, he too had known Budnick from the InsideOUT Writers group as a juvenile inmate in L.A. and stayed in touch.One day, he was on lockdown at Centinela when, out of the blue, officials told him he’d just gotten a new deal.

“They said, ‘I don’t know who you know, but you just got a transfer,” Alfaro recalls.

In the classroom at Norco, Budnick praised the inmates’ progress in a macho style that aimed to encourage without being saccharine.

“Hey Van Pelt!” he calls out to Don Van Pelt, the program’s administrator, within Alfaro’s earshot. “I’m shocked these guys know how to do PowerPoint presentations!”

Across the classroom, the intense Alfaro, whose left forearm is covered in tattoos, smiles.

To remain in the program, the students have to complete assignments as well as stay out of fights and gangs. “So far, we have not had any of Scott’s guys kicked out,” says Van Pelt, referring to Budnick.

The young inmates understand that if they foul up they’ll get sent back to the tougher prisons. “Not a lot of good opportunities come in life,” says Gerardo Vasquez, 19, of La Puente, serving time for armed robbery. “Scott gave us an opportunity, so now we got to take it and get the best out of it.”

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink