Naomi and the homeboys

October 28, 2010

His homies call him “Cranky,” and he’s the first to admit he doesn’t have much of a sense of humor. Nothing funny, he says, about his first 16 years of life, not with what he’s seen and done.

So when the do-gooder Israeli lady showed up at Camp Gonzales in the Santa Monica Mountains to talk to the incarcerated teenagers about how to have healthy relationships with women—specifically, girlfriends and wives—“I thought it was real corny, like it wasn’t for me.”

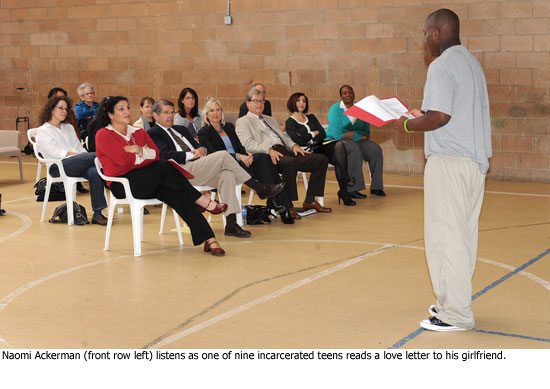

Yet here he is, standing before a small audience in the probation camp’s gymnasium this week, reading a love letter he’s written to his girl on the outside.

“I hope by the time you receive my letter, the sky is cleared up beautiful, and full of life, just like that special someone you are.”

One by one, eight more wards of the system quietly step forward, young men whose crimes—many of them violent—seems wildly out of whack with their boyish missives:

“No one can compare to the beauty I see in your eyes.”

“I need you in my life, I’m sorry for the damage that I caused you.”

“I love you and wanna be with you, but if you feel another man can treat you better than I can, let me know.

And so it goes, each letter followed by applause, each teenager exploring a tender side that few of them have seen in their own families, a side they believe can get them hurt in neighborhoods ruled by gang machismo. For now, though, they feel safe; none have mailed their letters—yet. As one author jokes, if his note hit his sweetheart’s mailbox, she’d say, “That’s not my boyfriend writing.”

And besides, mailing the letters isn’t really the point of Relationships 101, a pilot program created by American-born Israeli Naomi Ackerman and brought for the first time to one of the county’s Probation Department camps, where minors are sentenced for commitments of up to 9 months. It was funded with $3,500 from Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s office.

Ackerman says that the letters—combined with role playing, word association and improvisation—are a starting point for participants in probation camps or in high schools to understand the power of words to create sick or healthy relationships.

“Change has to start somewhere,” Ackerman says after the program’s culmination on Monday. “If you start by writing, then maybe you can say the words aloud and then, finally, begin to act more gently and compassionately…In the many squares of sorrow and horror in their lives, if one square can have peace and sanity and goodness, then I’m happy.”

***

In a sense, Ackerman’s relationship with the young men is proof of her premise. Although she’s had only about a half-dozen sessions with them since summer, you can see they like and respect her. An actress and playwright, she communicates directly and openly. Most important, when they speak, she listens. Ackerman knows that the challenges she faces here are far greater than those she’s confronted at private academies or public schools such as Fairfax High.

How many of you, she asks, have seen a relationship that’s lasted more than five years? Out of 10 participants, only two answer yes. Their grandparents, they say.

“When I listen to their reality on the street,” she says. “I don’t know how I can change that. I’m telling them to speak nicely to their girlfriends and then they go into their neighborhood and someone is going to shoot them in the face.”

Still, she got her captive audience to dial down their attitudes during four one-hour workshops, the first of which began with an excerpt from her powerful one-woman play, “Flowers Aren’t Enough.” It’s the story of a bright woman from an upper-middle class family whose husband gradually and brutally isolates her, before she finally reclaims her life. Ackerman has performed her play more than 1,000 times throughout the world.

But the real buy-in for the group, Ackerman says, came when she played the Annie Lennox song, Thin Line Between Love and Hate, in which a woman has been treated so badly for so long that she finally takes violent revenge on her man.

This, they get—a real-world consequence to the mistreatment that Ackerman’s been talking about. It touched a nerve for them all. “It made us calm down,’ says one participant, making them realize that, despite varying crimes and allegiances, “we had something in common.”

***

It’s nearly showtime at Camp Gonzales, a place that houses 90 minors between the ages of 16 and 18. Children’s advocates have praised the facility for its forward-thinking programs and emphasis on counseling and staff interaction. Which is not to say the place is soft.

Just days before the performance, Ackerman says, three of her participants are yanked and placed in lock-up for fighting. “Don’t take this away from them, too,” Ackerman says she begged, successfully.

Before the guests start arriving (they’ll include Yaroslavsky and the Probation Department’s new No. 2 man, Cal Remington), Ackerman lays down some of her own expectations for the nine fidgeting and distracted participants as they sit in a row of plastic chairs.

“I know it’s not in your nature, but it will not kill you if you smile,” she says, sounding like the Israeli military sergeant she once was. “You look like you’re going to a funeral. What these people think about you is that you only know how to be tough.”

She also gives it to them straight that their behavior could impact her hopes of getting more funding to expand Relationships 101 to other Probation Camps.

“Today is about money,” she says. “I’m not going to lie to you. But it’s also about you, what you’ve done.” So act accordingly, she warns. No grabbing your crotches or other kinds of street-posturing behaviors.

With the audience now seated and hushed, Ackerman tosses a rubber ball to one of the boys, who laterals to another. Each barks out a word that Ackerman says has no business in a relationship. Hate. Unfaithfulness. Unreliable. Dishonest. Cheating. Violence…Then the flipside. Trust, Respect. Commitment. Affection. Faith. Love…

With the audience now seated and hushed, Ackerman tosses a rubber ball to one of the boys, who laterals to another. Each barks out a word that Ackerman says has no business in a relationship. Hate. Unfaithfulness. Unreliable. Dishonest. Cheating. Violence…Then the flipside. Trust, Respect. Commitment. Affection. Faith. Love…

During the next half-hour or so, the teenagers perform role-playing exercises on how to handle situations (some don wigs to act as girlfriends) and, of course, they read their love letters. But the most revealing part comes during the unscripted session at the end, when the young men take questions from audience members whose lives would likely intersect with theirs only in a venue like this.

Surprisingly, they’re anxious to answer, seemingly energized by the reality that their visitors sincerely want to hear their opinions and experiences. Smiles suddenly come easily to them all.

Cal Remington asks how they’ll carry into the outside world the lessons they’ve learned in the program.

“Homies are kind of slow, you know,” one of them explains to the department’s second-in-command. “I’ll have to break it down for them, get it through their thick heads.”

Laughs all around.

A woman then asks what the young men would do if their sisters or mothers were being abused. One voice emerges above the others anxious to answer. He says he’d give him “some advice” to stop. “But I’m not gonna lie. If it’s my blood, I’m not going to let it go. I’d give him some of his own.”

Reality-check all around.

***

With the audience gone, Ackerman gathers her guys in a circle. “Incredible, incredible, incredible,” she says.

The boys don’t want her to leave. “I’m not saying good-bye,” she assures them. She says she’ll return to share with them a video she’s made of the event. Maybe, she says, they can perform at another camp, maybe one for girls. More smiles.

“I just want to say thank you, Naomi,” says one 16-year-old, confessing that “it was hard to do this in front of so many people.”

“A round of applause for Naomi,” says another of the teens.

And with that, their clapping fills the empty gym.

Posted 10/28/10

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink