How Westside subway got back on track

October 28, 2010

Twenty-five years ago, a methane gas explosion ripped through a Ross Dress for Less store in the Fairfax District, injuring nearly two dozen people and delivering a seemingly fatal blow to plans to build a subway along Wilshire Boulevard to the Westside of Los Angeles.

Twenty-five years ago, a methane gas explosion ripped through a Ross Dress for Less store in the Fairfax District, injuring nearly two dozen people and delivering a seemingly fatal blow to plans to build a subway along Wilshire Boulevard to the Westside of Los Angeles.

The area was designated a “methane gas hazard zone” and Congress moved swiftly to outlaw tunneling through the area.

Today, however, the subway is back. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority board on Thursday approved a locally preferred route for the Westside Subway Extension that would send the project through the once-banned territory. The board’s approval now moves the project into the final environmental review process.

“This is an historic day,” said Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, a member of Metro’s Board of Directors. “This is the first time in my lifetime, and in probably all of our lifetimes, that we have gotten this close, this far along the road to extending and building a public mass transportation line through the Wilshire Corridor.

“For all of the vicissitudes that we’ve had over the past quarter century,” Yaroslavsky said, “we finally are at the point where this is becoming more of a reality than a dream.”

The subway’s resurgence—one of the more remarkable comebacks in American transit history—came about in part because of more than two decades’ worth of technological advances, along with the findings of an expert peer review panel which led Congress to lift its prohibition at the urging of Rep. Henry A. Waxman.

“People had all but left it for dead,” said Raffi Hamparian, Metro’s government relations manager. He pointed to the evolution of new tunneling technology and the vote of confidence by the American Public Transportation Association’s peer review panel as two of the key turning points in the subway saga.

In a November 2005 report, the panel of nationally-acclaimed experts said it had unanimously determined that building the Westside subway, with proper procedures and technologies, poses a risk “no greater than other subway systems in the United States.”

As improbable as it might have seemed at the time, that March 24, 1985 blast, which sent flames shooting through fissures in sidewalks with its force, ended up becoming something of a galvanizing event in construction safety.

“We now have the benefit of hindsight. We also have the benefit of new technology,” said Dennis Mori, Metro’s executive officer of construction project management. He said lessons learned during the construction of Metro’s Red Line subway and Gold Line Eastside Extension will provide valuable guidance for tunneling through the gassy territory of the Wilshire corridor.

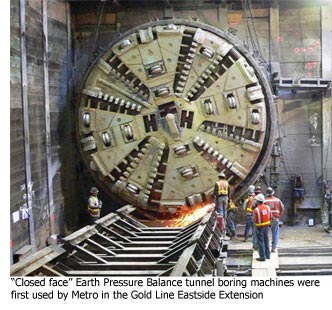

One of the biggest game-changers—literally—may be the “Closed Face Earth Pressure Balance” tunnel boring machine.

“The machine, fully assembled, is about the length of a football field,” Mori said. First used in L.A. during the Gold Line extension project that started in 2004, the machines offer operators greater control over how fast ground is displaced as they dig, lessening the risk of settlement and sinkholes.

The machines also can be outfitted with what Mori describes as “very robust ventilation equipment” to help workers avoid gas exposure while tunneling through the sometimes-challenging terrain that the Westside subway would need to traverse.

Dr. Geoffrey Martin, a USC professor emeritus and member of Metro’s tunnel advisory committee, said that advances in “slurry shield” tunneling technology also have made it safer for workers to remove gassy soil.

On Thursday, the board adopted a preferred route that would extend the Purple Line subway along Wilshire from Western Avenue to the V.A. Hospital. The route’s cost, about $4.2 billion in 2009 dollars, could rise to more than $5 billion by the project’s completion. All of the potential routes considered as part of the subway’s draft environmental impact process would have needed to pass through “an area characterized by oil and gas fields,” according to the project’s draft environmental report. “Therefore, hazardous subsurface gasses pose a significant hazard for all of the Build Alternatives.”

The draft environmental report listed a number of abandoned or idle oil wells in the area, also noting the La Brea Tar Pits’ “extensive tar sands” and high methane and hydrogen sulfide gas levels.

The Metro board also feels it can move forward with confidence because of years of successful underground projects since the Ross Dress for Less explosion.

Those include work by the city of Los Angeles’ Bureau of Engineering, which successfully tunneled through “almost 30 miles of similar gassy formations.” The bureau was commended by Cal-OSHA for successfully completing “the most dangerous tunnel job in the history of the state.”

More recently, LACMA’s new two-level subterranean garage, which opened in 2008, generated voluminous studies that have been provided to Metro to assist in the subway planning process. Under the proposed route, the Westside subway’s Fairfax station would be located next to the museum.

LACMA President and Chief Operating Officer Melody Kanschat said the museum, given its location beside the Tar Pits, approached the $33 million garage project cautiously, with substantial geological advance work, including boring into the ground to test for gas levels across eight acres at the site. And, with paleontological specimens in abundance—including a spectacular mammoth named Zed—great care also needed to be taken to safely preserve the fossils for the neighboring Page Museum.

She said that the Ross Dress for Less blast—once a dramatic catalyst for new building practices and technologies—seemed to be an increasingly distant memory for members of the public who weighed in on the garage project.

“Honestly, the methane is not as much of a concern for the general public as it was then,” Kanschat said. “The public was actually more concerned about the paleontological discoveries.”

That wasn’t the case, however, at Thursday’s Metro meeting.

The possibility of an underground explosion was among the many potential hazards cited by speakers from Beverly Hills, who turned out Thursday to voice their concerns about the possibility of tunneling beneath the city’s high school. While no final decisions have been made, the route under the high school is one of the options to be studied further under the plan adopted by the board.

Lisa Korbatov, vice president of the Beverly Hills Board of Education, read from a letter to Metro Board Chairman Don Knabe from a lawyer representing the school district:

“It is well known that the high school is located on a working oil field approved many years ago, with oil wells located onsite. The process of tunneling through the hazardous area underneath the high school imposes unacceptable explosion and cancer risks to the high school’s population”—risks, the letter said, that will never go away.

The Beverly Hills residents’ opposition centers on the placement of the subway’s Century City station. They oppose building a station on Constellation Boulevard because it would require tunneling under Beverly Hills High School. They favor an alternative that would run under Santa Monica Boulevard, which sits atop an earthquake fault. However, other speakers, from Westwood’s Comstock Hills neighborhood, spoke out in favor of the Constellation option.

Both options will be explored as part of the project’s final environmental review and preliminary engineering and design process. And, under a motion by Yaroslavsky that was adopted by the board in its vote Thursday, Metro staff was directed to fully explore all possible ramifications of the tunneling in Beverly Hills as well as from Century City to Westwood.

“Obviously, safety is the No. 1 issue for us,” Yaroslavsky said. “We will not build a tunnel that we believe is unsafe, whether it’s under the high school, or whether it’s under Santa Monica Boulevard or whether it’s under the residences in Westwood, or anywhere else in the County of Los Angeles.”

Another speaker, attorney Kenneth A. Goldman, called into question the safety of the machines Metro would use to build the subway, saying they had been linked to accidents in other countries, including Germany, Brazil, China and Korea.

But Metro board members and staff emphasized the safety records of recent local projects, including the Red Line to North Hollywood and the Gold Line Eastside Extension.

“In fact, on the Eastside Gold Line there wasn’t one single safety infraction for that entire period,” said Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, a Metro board member whose 30/10 initiative is seeking to accelerate building of the Westside subway along with other projects in the region.

Still, as Thursday’s board meeting made clear, the 1985 explosion’s after-effects are not being forgotten.

“We need to know what we have at every step of the way,” Yaroslavsky said, “where there’s an oil shaft, where there’s a methane pocket…and mitigate it and ensure that when we build it, our construction workers are safe. The people who live around the construction are safe. And when we finish it, the people who ride it are safe.”

Posted 10/28/10

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink