Ocean-friendly gardening starts here

February 6, 2012

Malibu made a prizewinning environmental “cleaning machine” out of a vacant lot that had been the community’s annual chili cook-off site. You don’t need to own a spread like Legacy Park, though, to help curb urban run-off.

Paul Herzog, coordinator of the Surfrider Foundation’s Ocean-Friendly Gardens Program, recommends “CPR”—conservation of water, permeability in your soil and retention devices such as rain barrels and rain gardens—to homeowners who would like to build water cleanliness into their landscaping.

And even small changes can help. Here are few:

Apply mulch. “It’s a simple thing to do, and it makes a big difference,” says Herzog. “Some areas even offer mulch from the city for free.” Mulching keeps weeds down, and, more importantly for the oceans, captures and holds water that might otherwise make its way down to the beach.

Redirect your rain gutter onto your landscape. Don’t let water wash over your roof and then send it directly into a storm drain. Turn your downspout or, if necessary, buy an attachment at the hardware store to send that water onto your lawn or garden, where it’ll do more good.

Reset your irrigation timers when you reset your clocks. You know how you spring forward and fall back for Daylight Savings Time? Well when you reset your clocks in the fall, adjust your irrigation to account for the rainier winter weather. And when spring arrives, set them again for the drier summer days.

Go native. Think about what naturally grows here the next time you landscape. Native plants don’t have to be dull. (Click here for ideas.) “Monarch butterflies journey from Canada to Mexico and there’s only one plant that baby Monarchs will feed on,” he says. “Milkweed. And some varieties are native to this place.”

Posted 2/6/12

Steering clear of bad fertilizer

November 16, 2011

Ah, November. The days are shorter, the light is sharper, and if you breathe deeply, you can almost smell the—whew! Maybe let’s not smell the air today.

Ah, November. The days are shorter, the light is sharper, and if you breathe deeply, you can almost smell the—whew! Maybe let’s not smell the air today.

Yes, fall is fertilizer season in Southern California. And as the autumn air grows pungent over the lawns of Los Angeles County, homeowners are being reminded to spread the wealth responsibly.

“The same nutrients that make your grass grow also will make algal blooms grow if they wash down the storm drains and into the waterways,” notes Susie Santilena, an environmental engineer in water quality at Heal the Bay.

The nitrogen and phosphorus that are so good for plants may contribute to toxic red tides in the ocean and can make algae run wild in freshwater areas like Malibu Creek, creating dead zones as the green scum blocks sunlight and inhibits the growth of other plants and animals, Santilena says.

The algae even wreaks havoc when it dies, because it sucks oxygen out of the water as it decomposes, a process known as eutrophication.

“When you don’t have oxygen in your waterway, your marine life suffocates and you get fish die-offs because there’s no dissolved oxygen in your water,” she says. “And there are aesthetic issues—algae growth can create pond scum, which is just kind of gross to look at in waterways.”

So what to do? It’s tricky, environmental advocates say, because while organic fertilizers such as steer manure and worm castings have advantages that chemical fertilizers don’t share, both can create destructive runoff if they aren’t applied carefully.

Manure tends to adhere to the soil better, so its runoff is less concentrated, but it also can introduce harmful bacteria into the water.

“I have a personal preference for worm castings for multiple other benefits, including environmental impact of production, but they can be overused like the other fertilizers,” says Santilena, noting that worm castings also can be hard to obtain in sufficient quantities for large-scale application.

“It’s how and when the fertilizer is applied that matters most.”

Environmental consultant and master gardener Curtis Thomsen, who conducts the Countywide Smart Gardening program, recommends a half-and-half mix of compost and fertilizer, sprinkled lightly over a lawn that has been aerated.

If you don’t have compost, he adds, there are sites in Los Angeles that offer free mulch that you can shred to make some and low-cost bins can be purchased at Smart Gardening workshops countywide. “The worms smell the organics in it and pull them down, which allows water to penetrate deeper,” he says, adding that compost is especially good for getting nutrients to the roots of thick grasses that tend to thatch. Also, he says, if you add that mixture to your garden plot this fall, it will improve yields, reduce disease in the soil and produce healthier, stronger plants next year.

Meanwhile, Rudy Valenzuela, regional grounds maintenance supervisor for the county Department of Parks and Recreation, notes that the county aerates and fertilizes its park lawns with a commercial chemical blend of nitrogen, potassium and iron that is geared to its sturdy mixture of grasses. He notes, however, that the crews wait until after dark to water and then do it judiciously, turning off the sprinklers after about 15 minutes per station to avoid runoff.

Both approaches keep in mind the need to keep your fertilizer on your own grass. Here are some dos and don’ts from Heal the Bay:

– Do use fertilizer as sparingly as possible, no matter what type you use. Less is more.

– Don’t ever apply fertilizer right before a rainstorm, and never overwater after applying. Too much water will just lift your fertilizer and wash it off.

–Don’t apply to highly compacted or steeply sloped grasses, which also prevent fertilizers from fully soaking into the soil.

–Do consider creating a rain garden, using rain barrels and other containers that will keep rain in your hard and out of the street.

Posted 11/16/11

From pit to park

September 14, 2011

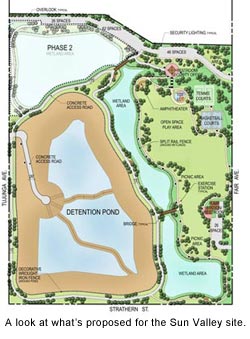

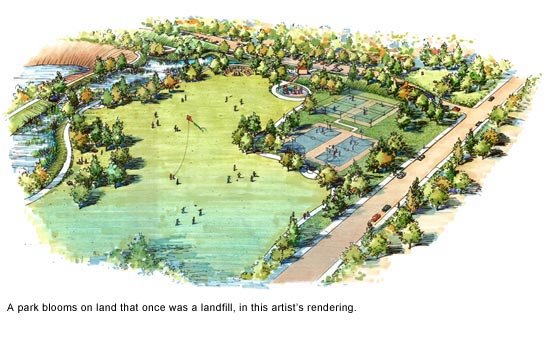

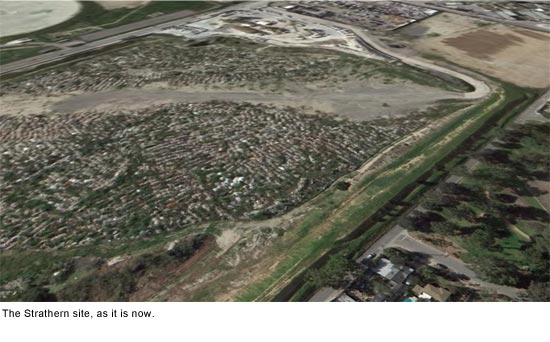

It’s not much to look at now. But when Sun Valley’s Strathern Pit is reborn as the Strathern Wetlands Park, the new facility is expected to offer picnic spots, walking trails, basketball and tennis courts, an exercise station, wildlife habitat and landscaped ponds.

Those water features aren’t just ornamental—they are being designed to play an important role in diverting and treating storm water runoff.

The multifaceted approach promises to bring beauty and usefulness to the 46-acre site, which until 2009 was used as a construction debris landfill.

The multifaceted approach promises to bring beauty and usefulness to the 46-acre site, which until 2009 was used as a construction debris landfill.

The park’s proposed recreational features were developed at a community workshop in April. Get a look at what’s being planned at a community meeting this Saturday, September 17, at the Richard E. Byrd Middle School Auditorium, 8501 Arleta Avenue in Sun Valley. The meeting runs from 10 a.m. until 1 p.m. Reservations aren’t required but if you’d like to RSVP, you can do so by contacting project manager Mark Lombos at (626) 458-7143 or by emailing [email protected].

Construction on the wetlands park is expected to begin in the fall of 2013. The $50 million project is being funded by the Los Angeles County Flood Control District, City of Los Angeles Proposition O and the City of Los Angeles Department of Water and Power.

A “Great Wall” becomes even greater

August 30, 2011

Every city has its hidden treasures. Take “The Great Wall of Los Angeles”.

Every city has its hidden treasures. Take “The Great Wall of Los Angeles”.

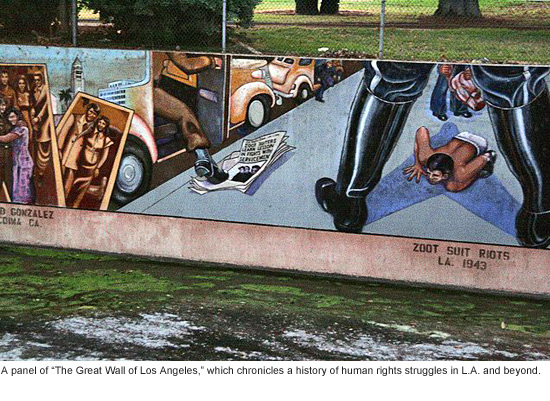

More than three decades old and 13 feet high, it unfurls like a vibrant tattoo for nearly a half-mile, recounting the history of human struggle and achievement along a concrete retaining wall in the Tujunga Flood Control Channel.

Flanked by a narrow park, it’s easy to miss what’s believed to be the longest mural on the planet. And yet it is this singular work—painted by hundreds of hands in the course of five summers—that launched Los Angeles’ reputation as the world’s mural capital.

Despite such rich origins, few public artworks have had to endure so many indignities. It’s been soiled by car exhaust, corroded by smog, bleached by fertilizer runoff and baked by the relentless sun of the San Fernando Valley. What’s more, political crosscurrents over the decades have generally put the kibosh on obvious possibilities for expanding the project, even as its once radical-seeming material—from the sins of the Spanish missionaries to the Japanese internment—has crossed into the historical mainstream.

“One would think it would have completely disappeared by now, given all it’s gone through,” marvels Judy Baca, the Watts-born activist, artist and UCLA professor whose vision has, since 1976, been the guiding light behind the project. “But what’s remarkable is how much of it is still there.”

Los Angeles has more than 3,000 murals, and their upkeep has been an ongoing civic battle. But next month will bring good news from “The Great Wall.”

For the past three years, Baca and a crew of artists, volunteers and interns have been painstakingly restoring the artwork. In mid-September, the project is expected to be finished. A ribbon-cutting and celebration are being planned for September 17 at the park near the wall, which lies between Burbank Boulevard and Oxnard Street off Coldwater Canyon Avenue. (Click here for driving directions.)

For the past three years, Baca and a crew of artists, volunteers and interns have been painstakingly restoring the artwork. In mid-September, the project is expected to be finished. A ribbon-cutting and celebration are being planned for September 17 at the park near the wall, which lies between Burbank Boulevard and Oxnard Street off Coldwater Canyon Avenue. (Click here for driving directions.)

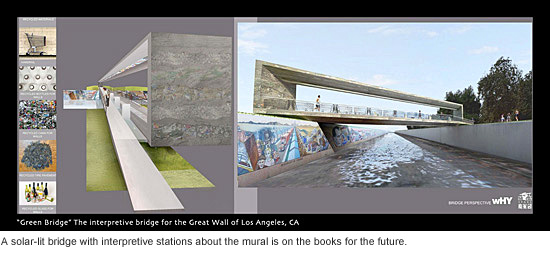

After that, Baca says, signage, lighting and a solar-lit “green” bridge with interpretive stations will be added, the better to see and understand the monument to L.A.’s multi-cultural history.

The entire $2.1 million improvement—spearheaded by the Venice-based Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC), with funding and assistance from the City of Los Angeles, L.A. County, the California Cultural and Historical Endowment, the Rockefeller and Ford foundations, the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy, Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s office, and others—should be finished late next year.

That, in turn, will set the stage for a fundraising drive to finish the next four decades of the mural (it now stops in the 1950s) using already-designed sketches that will take the narrative through the Vietnam War and the Los Angeles riots up to the 21st century.

For Baca, now an iconic figure on the Los Angeles art scene, the restoration is both a personal and civic milestone. A one-time high school art teacher in the San Fernando Valley, she has spent the better part of her life as a fiery advocate for public art.

As a summer art teacher in 1970 for the City of Los Angeles, she organized rival gang members in East Los Angeles to paint “Mi Abuelita,” a mural of a grandmother with outstretched arms that for many years was a Hollenbeck Park landmark. The project landed Baca a job as the head of a citywide mural program manned by at-risk teenagers, and led from there to the creation of SPARC, the nonprofit community arts organization.

“The Great Wall,” commissioned by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers at the behest of the L.A. County Flood Control District to help improve the area around the Tujunga Wash, was SPARC’s first project. Since then, SPARC, for which Baca is artistic director, has produced hundreds of murals throughout the city, commissioning hundreds of artists and training thousands of youth apprentices.

More than 400 at-risk youths, along with scores of artists and historians and hundreds of community members, worked on “The Great Wall” between 1976 and 1984, when painting stopped due to rising costs and safety concerns and the changing political climate during the Reagan Era. Many of those who worked on it found the experience to be life-altering, as this video recounts.

Although the mural’s initial segments were designed by at least 10 artists, each taking a different historical period, it was Baca who created the overall aesthetic beginning with the 1920s mural panel. When the “Great Wall” was started, she was 30. By the time she and her crews celebrate its restoration, she’ll be a week shy of 65. Time, she laughs, has taken a toll on the artist as well as the art.

“We have a funny thing going on down there,” she says of the restoration. “We have the senior citizens, who aren’t body-agile but have great hands, and then we have the younger ones, whose hands aren’t as adept but who have the bodies to continue. We’re transferring knowledge and teaching them to collaborate—it’s a very important moment.”

But, she adds: “I think this will be my last year on the channel. It’s incredibly physically demanding. I think it’s time for the younger people to take over.”

Meanwhile, she says, she’s had the privilege of revisiting a formative period in her life.

“I’m having these dialogues with my younger self on a daily basis,” she says. Simple decisions—what color to use in restoring the image of an Okie, or whether to underscore the Madonna-and-child subtext of a migrant worker holding a baby—“give me this visual of who I was when I painted it,” Baca says.

“That Judy was working with this incredible passion. She had boundless energy and this incredible willingness to put it all out there. This Judy, at 65, would probably say, ‘This is way too hard.’”

If she had to do it all over again, she says wouldn’t change a thing.

Although the project, in retrospect, was an “incredible marathon” and a massive undertaking, she says, it also was “a great labor of love”—and of youthful idealism.

“I may have much more wisdom now, but that girl was limitless,” says Baca. “She was limitless.”

Boom times on the L.A. River

March 31, 2011

When the heavens open, as they did epically last month, the Los Angeles River becomes a roaring, churning testament to urban junk and waste.

When the heavens open, as they did epically last month, the Los Angeles River becomes a roaring, churning testament to urban junk and waste.

With a collection area of nearly 900 square miles, it carries in its rain-swollen waters anything that can be chucked into flood-control channels or pushed down curbside catch basins—sofas, stereos, soccer balls, spray paint cans from taggers, whatever.

Then there’s the trash, layers of plastic bags and Styrofoam mixed with tangled vegetation mowed down by fast moving waters on the river’s channel bottom, where it’s been allowed to grow wild again.

At the end of this mucky 51-mile journey to the sea is Jared Deck of Los Angeles County’s Public Works Department. He oversees a multi-million dollar operation in Long Beach to corral all that junk in a boom unfurled across the river, just north of the Queen Mary and the harbor. Think of it as a goal line stand.

At first, it’s hard not to be caught off guard by Deck’s youthfulness in a bureaucracy in which some guys have been on the job longer than he’s been alive. But then you learn that the 26-year-old is a Hermosa Beach surfer with a unique feel for the value of his job—and those of his colleagues in the Flood Maintenance Division—every time he paddles into the water.

“It’s fulfilling,” Deck says. “My playground is the outdoors so I enjoy doing anything I can to make it better.”

In March, the stakes were historically high for him and the boom, which was first placed across the river 11 years ago as a pilot project. More dammed up debris—460 tons of it—was hauled out of the water than at any time before, tangible evidence of the severity of the March storms. The tonnage included full, uprooted trees. (See video below of the boom in action.)

To be sure, the county, along with its private and government partners, has worked hard to significantly reduce the amount of debris and pollutants flowing into the Los Angeles River from a watershed area of nine million people.

Among other things, county officials have installed 11,000 catch basin screens and other devices in unincorporated areas and have encouraged cities across the region to do the same. They’ve also launched ad campaigns to discourage dumping and educate the public about the relationship between the ocean and what they wash down their driveways.

Still, during the storm season between October and April, all bets are off. Those catch basin inserts, for example, are designed to unlock so greater loads can be accommodated and street flooding can be reduced. And, with as much as 330 million gallons a day flowing through the river, there’s little to do but wait for the debris to hit the boom.

Formerly called the Los Angeles River Trash and Debris Collection System, the boom is operated by a private contractor, Frey Environmental of Newport Beach. On Tuesday, the Board of Supervisors renewed Frey’s contract for an annual sum of $795,000, with a 66-month maximum of about $4.4 million.

Formerly called the Los Angeles River Trash and Debris Collection System, the boom is operated by a private contractor, Frey Environmental of Newport Beach. On Tuesday, the Board of Supervisors renewed Frey’s contract for an annual sum of $795,000, with a 66-month maximum of about $4.4 million.

Since Frey first got the business in 2003, Dave Duncan has been there for the company as one its site operation managers. During the past eight years, he says he’s seen it all, including the sad discovery of a 35-year-old woman’s body. “I thought it was a mannequin,” he says.

Duncan says he understands why there’s so much old junk that ends up at the boom, where it’s lifted into dumpsters by cranes with “grab buckets.”

“If you’re on the low end of things, making $8 an hour and you don’t have money to go to the dump, what do you do? You throw it in the channel and hope for the best,” he says.

The experience and continuity that Duncan has brought to the operation gave a sense of confidence to Deck, who, in 2008, was assigned by the county to work directly with the contractor. “Whenever I’m on the site, Dave is always there,” says Deck, who was promoted last fall and now supervises the person who got his old job.

Deck grew up in central Maine—“in the middle of the woods”—and attended an engineering school in Worcester, Mass. Deck says he was quickly recruited by Los Angeles County before hiring freezes ended such efforts.

The recruiter, a Boston native, took him straight to the beach. “I was sold from there,” says Deck, who had learned to surf while studying abroad in Puerto Rico. An avid skier, too, he now lives in a Hermosa Beach apartment.

In his short number of years here, Deck says he’s had a great vantage point for seeing the success of efforts to keep the ocean cleaner by diverting runoff and trapping debris. “When I go surfing,” he says, “the water quality is significantly better…It’s great to see the system functioning and working.”

The boom in action

And here’s something you can do: Join the Friends of the Los Angeles River’s 22nd annual cleanup on Saturday, April 30th, from 9 a.m. to noon. The details are here.

Posted 3/31/11

Malibu’s worthiest of waves

October 7, 2010

It has starred in more than 75 movies. It is the namesake for one of California’s best known environmental groups. And its “original perfect wave” has made Malibu a Mecca for generations of surfers.

Now Surfrider Beach—the birthplace of modern surfing in California—will add yet another accolade to its long list of laurels: On Saturday, it will officially be dedicated as the nation’s first World Surfing Reserve.

“These special surf spots are the Yosemites of the coast,” said Dean LaTourrette, executive director of Save The Waves Coalition, a non-profit environmental organization based in Santa Cruz County that has spearheaded the international initiative to designate and preserve iconic surfing coastlines worldwide.

“People need to understand how valuable and fragile they are, and the World Surfing Reserve designation will help the international and local communities focus on protecting them.”

Although the World Surfing Reserves designation is purely honorary and will have no regulatory authority or impact, LaTourrette said the groups involved hope it will raise awareness. The designation, modeled after a successful Australian program that has singled out more than a half-dozen of that continent’s beaches, was inspired, he said, by UNESCO’s World Heritage Sites, which help preserve locations of cultural significance.

The Malibu reserve, he said, will be the first in a series of World Surfing Reserves—“a UNESCO of surfing”—planned for pristine coastlines in Australia, Hawaii and other important surf destinations.

Surfrider Beach, formally known as Malibu Lagoon State Beach, lies near the Malibu Pier on the northern arm of Santa Monica Bay. Although it has been plagued over the years by crowds and water quality issues, its long, smooth-breaking waves are considered the “definitive California pointbreak,” according to “The Encyclopedia of Surfing” by former Surfer magazine editor Matt Warshaw.

Surfrider beat out more than 125 nominees for the inaugural designation, including Trestles, Mavericks, Waikiki, Manly Beach in Australia and breaks in Indonesia and Europe. The choice, LaTourrette said, was based in part on the long fight surfers have waged to help keep it clean.

Situated at the mouth of the Malibu Creek watershed and Malibu Lagoon, Surfrider’s history has been entwined with the environmental movement since the late 1960s, when runoff began fouling the lagoon with waste and sewage. In fact, the Surfrider Foundation, one of the state’s most dogged environmental groups, was founded as a response to Malibu’s environmental issues.

The World Surfing Reserve designation “is a statement by the global surfing community that Malibu is extremely important to surfing and should be protected,” said Chad Nelsen, the Surfrider Foundation’s environmental director.

“Of course, WSR do not have any legally binding protection, so the real value of the WSR will be demonstrated by local and global support for the protection of Malibu.”

In recent years, a number of public and private sector initiatives have been undertaken to reduce the pollution that has long plagued the waters of Surfrider—the most recent being Malibu’s newly opened Legacy Park.

Beneath the $38-million project is a network of pipes and filters designed to remove bacteria and contaminants from stormwater runoff in Malibu Lagoon, Malibu Creek and Surfrider. Among the governments donors was L.A. County, which contributed $700,000. Private donors included Rita Wilson and Tom Hanks, Don Henley, Rob and Michele Reiner, the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation and the Marilyn and Jeffrey Katzenberg Family Foundation.

As part of the surfing reserve designation, a local stewardship council has been created to help coordinate and publicize Surfrider’s various preservation efforts. Members so far include such local surfing legends as Allen Sarlo, Andy Lyon and Steven Lippman, community leaders such as Michal Blum of the Malibu Surfing Association and Jefferson “Zuma Jay” Wagner, the wave-riding mayor of Malibu.

“We’re the local ones who will keep an eye on it,” said Wagner, adding that the designation will be invaluable as a fundraising and advocacy tool.

“The social stigma of messing with a preserve may not be much to a lawyer, but, boy, to the general public, that’s a battle cry.”

The dedication on October 9 will begin with a sunrise ceremony on the beach and a blessing by local Chumash leader Mati Waiya, followed by a paddle-out, a formal dedication at 11 a.m. and an evening celebration at Duke’s Malibu.

California Coastal Commissioner Ross Mirkarimi said the commission has already adopted a resolution supporting the World Surfing Reserves program, which he said “will benefit not only surfers, but also the greater coastal community.”

Posted 10/07/10

More L.A. beaches acing their tests

May 27, 2010

The grades are in, and water quality at Los Angeles County beaches improved significantly last year, according to environmental watchdog Heal the Bay’s statewide 2009-10 Beach Report Card.

The latest report, released this week, gives 79 percent of the county’s beaches an A or B grade during the dry-weather summer season, up significantly from last year’s 70 percent and from the six-year average of 73 percent. The report uses a complex scorecard based on weekly measurements of bacterial pollution between March 2009 and April 2010 at 326 California beaches, including 86 in L.A. County.

The latest report, released this week, gives 79 percent of the county’s beaches an A or B grade during the dry-weather summer season, up significantly from last year’s 70 percent and from the six-year average of 73 percent. The report uses a complex scorecard based on weekly measurements of bacterial pollution between March 2009 and April 2010 at 326 California beaches, including 86 in L.A. County.

Heal the Bay President Mark Gold says the improved grades are the result of efforts to clean up water runoff from streams and storm drains. “These pollution cleanup projects are beginning to pay dividends,” he said.

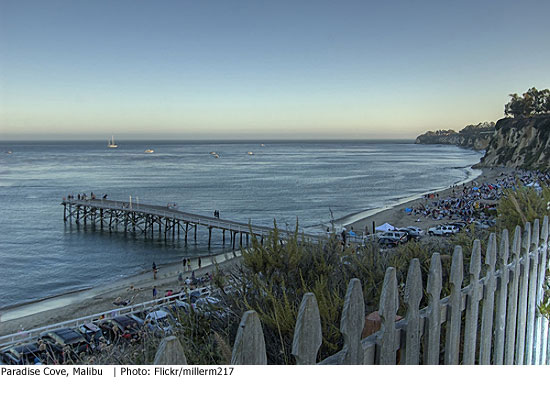

Failing grades at two troubled Malibu beaches last year jumped to B’s this time, thanks to recently-installed cleanup systems. A county Department of Public Works project at Marie Canyon launched in late 2007 zaps bacteria-tainted water with ultra-violet radiation before returning it to the creek that empties into the ocean at Puerco Beach. At Paradise Cove, the cleaner flows correspond with the completion of new privately-owned sewer and waste water treatment systems.

Despite the good news, Los Angeles County’s overall water quality remains the worst in California. Seven local beaches earned an F in year-round testing—down from 15 last year, but still troubling, Gold said.

Five local beaches made the group’s “Beach Bummers” list of the worst summer-season spots. The bummers include beaches at Avalon Harbor Beach on Catalina; Cabrillo Beach in San Pedro; Santa Monica Pier; Colorado Lagoon in Long Beach; and Sunset Boulevard and Pacific Coast Highway in Pacific Palisades.

Even with cleaner beaches, Gold counsels swimmers to stay out of water near creek mouths or storm drains. “If it’s an open-ocean beach, it’s a clean beach,” Gold said.

For Heal the Bay’s press release on L.A. region beaches, click here.

Posted 5/27/10

Let’s fix this elections mess

February 18, 2010

Voters in parts of the San Fernando Valley may cast ballots four times this year for the same office–with two of those votes coming in a single day.

Voters in parts of the San Fernando Valley may cast ballots four times this year for the same office–with two of those votes coming in a single day.

No one loves elections more than I do, but we all know it’s possible to get too much of a good thing.

This bizarre case of election overkill going on now in the 43rd Assembly District is the latest manifestation of the growth of special “vacancy elections” in Los Angeles County and throughout California.

The need for these extra elections is driven by term limits, as termed-out officials leave one post early after winning election to the next. And it’s becoming clear that the increasing need for such elections saddles taxpayers with burdensome costs and runs the risk of driving up voter fatigue and apathy.

Ground zero right now is the 43rd District, which includes Glendale, Burbank and a slice of the San Fernando Valley. Voters there are preparing to go to the polls on April 13 to pick a successor to serve out the final months of the Assembly term of Paul Krekorian, who left to join the L.A. City Council.

And April 13’s election is just the beginning. If no candidate gets a majority that day, there’ll be a runoff on June 8.

But it just so happens that June 8 is the same day as the regular primary election, in which there’ll be –you guessed it – a second slate of candidates on the same ballot vying to win the next two-year term that begins in December.

So in effect, voters would have to make a short-term pick and a long-term pick on the same ballot. And the list of names may well overlap. Talk about confusing.

This ordeal-by-ballot-box would finally end in November, when exhausted voters could select Krekorian’s long-term successor in the general election.

There are two basic problems with this system. It does a disservice to taxpayers by driving up cost. The April 13 vote, for instance, may cost us an extra $1 million. And it does a disservice to voters because holding elections at unexpected times of the year depresses turnout.

So what’s to be done? If we could fix the problem locally, we would. But it’s state law that dictates how and when elections are run, and the county can’t unilaterally make improvements. The onus is on the Legislature and the governor.

One place they could start is by doing a better job of covering expenses related to the elections. The state does cover some costs, but the current system is cumbersome and reimbursement is spotty. We in Los Angeles County have paid more than $12 million for special vacancy elections in the past decade, but only got about $4 million back from the state. That needs to change. So earlier this month State Sen. Curren Price introduced a bill that would guarantee future payments in all special elections.

Clearly, though, for most taxpayers the bigger issue is not who foots the bill, but how to fix the underlying issues that got us here.

And for some fresh thinking on that, we need look no further than our own Registrar-Recorder/County Clerk, Dean C. Logan.

Logan, a nationally-recognized expert on election policy and reform who’s been supervising L.A. County elections since he was appointed to his post in 2008, argued persuasively for change in an opinion piece this week in the Los Angeles Times. I completely agree with his contention that by holding too many special elections we drive up both taxpayer costs and voter discontent.

His suggestions for solutions range from holding special elections only on already scheduled election dates to instant-runoff voting. There’s even the option of using a hybrid system, as some states do, to allow short-term appointments to fill vacancies until consolidated elections can be held.

Personally, I’m not yet certain which of these suggestions will ultimately be most effective. But I’m sure of one thing. In a time of strained county budgets and alienated voters, doing nothing is not an option.

Posted 2/18/10

Not so much trouble in Paradise (Cove)

October 29, 2009

They set out to solve one mystery, but they ended up with another.

First, the good news: An unusual three-year research partnership has found that the water quality at Malibu’s Escondido and Paradise Cove beaches is dramatically better than expected. Now the puzzling news: Nobody knows why.

“It’s like you hired Scotland Yard to solve a murder and three weeks later the dead person walks in and says, ‘Whatcha doing?’ ” says Steve Weisberg, executive director of the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project, which is running the study with $800,000 in funding from Los Angeles County. “We were hired to find the source of the problem….Where we’re at is a point of frustration.”

When the project started in May, 2006, the targeted beaches stood out as significant problem areas, according to Mark Gold, president of Heal the Bay, which has participated in the research along with the county Department of Public Works.

“Escondido was the most polluted beach we had ever seen,” Gold says. On the group’s annual Beach Report Card, he says, “I think it got a zero one year.” (Now Escondido Creek, just east of Escondido State Beach, and Paradise Cove Pier at Ramirez Canyon Creek mouth are both on the group’s honor roll.)

Back then, Gold suspected that the pollution was coming from “illegal dumping of tremendous amounts of horse manure” and maybe also from waste discharge problems from a nearby restaurant and some mobile homes.

All this added up to an opportunity for some collaborative detective work, bringing together the county and its sometime-adversary Heal the Bay, which has pushed hard for more aggressive government enforcement of clean water regulations.

The Southern California Water Research Project was “brought in as a neutral party,” Weisberg says, adding that he thought the best way to achieve a détente was to have everyone in the field “taking samples together.”

At their disposal was an array of scientific tools – including tests for optical brighteners found in laundry detergent to learn if household wastewater was involved. (For more on those, click here.) Overall, the prospects for finally determining whodunit (or whatdunit) looked good.

“The problem,” Weisberg says, “is that we just have not found strong, recurrent problems at that beach.”

One theory holds that a series of unusually dry winters led to a temporary improvement in the bacteria levels flowing from Escondido and Ramirez creeks into the bay. Another scenario posits that someone was illegally dumping, found out about the study in progress and decided to clean up his or her act. Or maybe different testing methods yield a different result? “We don’t know,” Weisberg says, “but we know it stopped.”

Weisberg says the hunt will continue in the coming year, with some discussion of testing to determine whether “birds pooping on the beach” mighty be to blame for the pollution, rather than problems in the watershed.

Gold, for his part, thinks it’s probably not worth continuing the testing effort unless there’s significantly more rainfall this year, which would bring more runoff to analyze. He does, however, advocate keeping an eye on a restaurant at the “very lowest part of the watershed.”

“You never get to pack your bags and go home,” says Gold, who praises Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky for responding to long-running concerns about the beaches’ bacteria levels and pushing for funds to study the problem. “I’m glad we did it,” Gold says. “I think it put a lot of people’s minds at ease.”

Mark Pestrella, deputy director of water resources for the county Department of Public Works, says he also is glad the study went forward and wants to see it continue for a fourth year. “The supervisors and the constituents out there really want to know that these beaches are safe,” Pestrella says.

“The study helped us set up protocols that were not in place before….Methods of sampling, the health department’s and Heal the Bay’s, were tried side by side,” he says. “It gave us more information on the percentage of the problem we should allocate to humans. Although we didn’t actually break down every source, we eliminated several areas. In Escondido, we were able to say we did not find a human source of indicator bacteria at the beach.”

The bottom line, Pestrella says, is that the study so far has “bettered the county’s understanding of how to monitor and test for indicator bacteria. It very much put science in front of rhetoric.”

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink