Going Green

A farewell to lawns

July 17, 2014

Start saying so long to the lawns of Southern California.

As the realities of climate change and drought have begun to sink in statewide, local figures indicate that homeowners have finally begun—gradually—to let go of their grass.

Amid new state conservation mandates and growing financial incentives, thousands of lawns and millions of square feet of green turf have disappeared during the last three years in Los Angeles County, much of it during the past year of record-low rainfall.

The reason? Outdoor irrigation is now consuming an estimated 50 percent of the average water bill.

This week, in an unprecedented action, the State Water Resources Control Board made it a statewide criminal infraction to waste water, particularly on landscape irrigation. Meanwhile, cities throughout the county have upped turf removal incentives encouraging homeowners to go drought-tolerant, at least in their front yards.

The moves have accelerated a trend that is already approaching critical mass in Southern California, even as they reorder a landscape that has long characterized the region.

“It’s slow, but things are really changing,” says Matthew Lyons, director of planning and water conservation for the Long Beach Water Department.

“Three of the last four years have been dry and this last winter was catastrophic. There’s just not a future here for grass lawns.”

Acceptance of that reality hasn’t been easy.

“People have had a hard time letting go of their beautiful green sward,” says Lili Singer, director of special projects and adult education for the Sun Valley-based Theodore Payne Foundation, a native plant organization that has done a land-office business this year helping county homeowners rethink their landscapes.

“Everybody on the block has the same setback and the same yard and people don’t want to be the oddball,” said Singer. “But there’s also this thing about having an estate.”

“It’s an enormously emotional thing,” agrees Stephanie Pincetl, director of the California Center for Sustainable Communities at UCLA. “People’s property values are tied up in it. And there’s the sort of iconic manliness in having a good-looking lawn that’s reinforced by TV programs and ads and all sorts of cultural messages.”

Generations of L.A. suburbanites can attest to this cultural attachment, whether they grew up tending the dichondra around a San Fernando Valley ranch house or assiduously edging the Bermuda grass at a Mid-Wilshire cottage.

Pincetl said that when she replaced the grass on the median strip of her small condominium complex last year with colorful, drought-tolerant plantings, a neighbor sent her a note accusing her of “threatening to destroy the aesthetic of the street and overpower the parkway.”

Cultural historian Ann Scheid says that aesthetic dates to the 1800s, to East Coast settlers who “imported their architecture from the East, and imported their lawns, too.”

Though a native plant movement did crop up here in the 1890s, she said, it didn’t catch on then because many of the large estates were second homes whose owners only visited during the winter.

By 1912, she noted, Los Angeles also had the L.A. Aqueduct, and, later, the Metropolitan Water District, which imports water from the Colorado River.

“So we never really had to face the problem,” she says. “Until now.”

Now, with climate change heating an already arid and densely populated region, conservation has become a mantra.

Some communities have been ahead of the curve: In Santa Monica, where no-grass lawns have become common, a pair of decade-old demonstration gardens have helped show the value of drought-tolerant landscapes, not just in water savings but in diminished labor and green waste.

The City of Los Angeles has imposed mandatory water conservation rules on homeowners since 2007, including alternating watering days and a ban on daytime lawn sprinkling. The city Department of Water and Power says the strategy has cut L.A.’s water use by 17 percent over the last seven years.

Also useful have been MWD’s conservation incentives and turf removal rebates, which have been increasingly adopted by member cities this year as the drought has worsened. The MWD rebate doubled in May to $2 per square foot, an incentive that can be augmented by member cities. In Los Angeles, the rebate is $3 per square foot; in Long Beach, it’s $3.50.

The program has prompted more than 1,900 L.A. homeowners to switch from grass to “California Friendly” landscapes during the past three years; in Long Beach, the toll has been 1,300 lawns, including 433 so far this year.

“I have a lot of cactus now, and perennials and lavender and lily of the valley,” says Long Beach resident Argy Abel, who took advantage of her city’s program two years ago, and is now one of three homeowners on her block alone to have gone grass-less.

Even smaller programs have made a mark: Though only a limited number of water users have qualified for the Los Angeles County Department of Public Works’ turf replacement program, the “Cash for Grass” incentive has made more than 250 grass lawns disappear, mostly in the Antelope Valley. And that’s not counting the people who went drought-tolerant on their own.

Still, some neighborhoods remain cautious. Beverly Hills, for example, not only has a longstanding lawn culture, but also supplies about 10 percent of its own drinking water through a municipal water treatment plant.

There, turf replacement incentives haven’t found many takers, though the city has had some luck with voluntary conservation and a high-tech, remote leak detection system, says City Manager Jeff Kolin. He says that with the new state mandates, “we’ll probably be adding some more incentives and enforcement.”

Good luck, says Peter Eberhard, a Westside landscape designer, who notes that wealthier homeowners tend to have bigger lawns and less sensitivity to the price of water.

“No one is calling us and saying, ‘Oh, I’m concerned about this drought, please take my lawn out’,” he laughed.

Posted 7/17/14

Green river milestone

July 10, 2014

Improving the Los Angeles River has become a local cause célèbre, with increasing numbers of Angelenos pushing to transform the concrete channel into a place where people can exercise, play and relax.

This Saturday, L.A. County takes a big step toward that goal when it opens the L.A. River Headwaters Project, which is located at the river’s official beginning—the convergence of Calabasas and Bell creeks in Canoga Park.

The $11.5 million project is the river’s largest greenway improvement so far, with 2.5 miles of upgrades that benefit the public and the environment. Cung Nguyen, the river’s watershed manager for the Department of Public Works, said the opening is an important milestone.

“If we improve the beginning and end of the river, then we can start filling in all the gaps,” Nguyen said. “Ultimately, the grand picture is to provide connectivity for recreation along the whole river.”

Joggers and bicyclists will gain access to 2.5 miles of new trails (1¼-mile in each direction) on which to ride and run, passing safely under street crossings and over pedestrian bridges. Rest areas with benches will provide pit stops for those who prefer to take a slower pace.

Native landscaping replaces the former backdrop of an access road and chain link fencing. It also creates new habitat for wildlife, including 300 species of migratory birds that rest their wings by the river. Maintenance crews have been trained to know when nesting seasons are so they won’t disturb the avian guests as they pass through.

The project is still designed to help prevent devastating floods while reducing the amount of urban runoff with bioswales—subsurface plant and sediment-filled structures that let water seep into the ground to be filtered naturally rather than getting fast-tracked, pollutants and all, into the ocean. Nguyen estimated that up to 587,000 gallons of water will be recaptured in an average year.

The headwaters project is funded by the county Flood Control District, along with a $1.8 million grant from Prop. 84, a state initiative dedicated to improving water systems. The project originated with the 1996 L.A. River Master Plan, which recognized the waterway’s importance as a natural resource and targeted publicly-owned lands for future projects. More than 50 of those projects have been completed to date, with another 50 or so to come. Coming up are more greenways like the headwaters project as well as things like wetlands, parks, bike paths and kayaking programs. Just last month, another San Fernando Valley greenway, the half-mile Valleyheart Riverwalk project, opened between Studio City and Sherman Oaks.

While those project-by-project efforts continue, a $1 billion revitalization plan approved by the Army Corps of Engineers in May is expected to drastically improve a sweeping 11-mile section of the river between downtown L.A. and Elysian Park.

But every piece matters; even after the entire river is revitalized, few people will use all 51 miles of it in a single day. The local community of Canoga Park stands to benefit most from the headwaters project, something that Luis Rodriguez, principal of Canoga Park High School, is keenly aware of. His school sits just west of the headwaters. He sees a great educational opportunity for his students, who have been focusing on topics like water conservation and drought-resistant plants in the context of one of California’s most severe water shortages on record.

“For our school it makes a huge difference, but it’s going to revamp the entire community in a positive way,” Rodriguez said. “There’s so much industry in our area, but living spaces where people can have fun? That’s something that is really needed.”

The official opening ceremony takes place at 11 a.m. on Saturday, July 12, at DeSoto Avenue and the Los Angeles River in Canoga Park, 91303.

Posted 7/10/14

Moving forward at Descanso

June 11, 2014

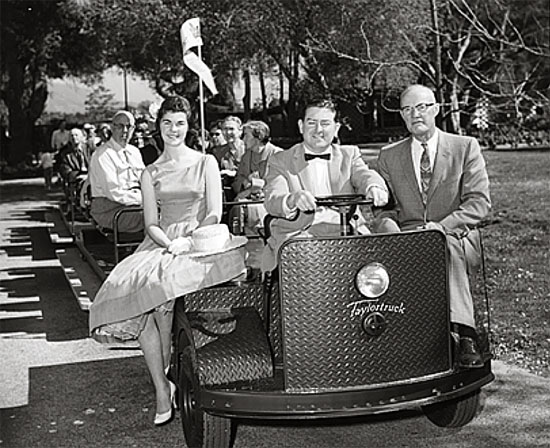

Trams have been a fixture at the gardens since the 1960s. But they've now come to the end of the road.

When an early morning fire engulfed a storage structure at Descanso Gardens in January, a bit of history went up in smoke. And maybe that wasn’t so bad, admits the garden’s executive director, David R. Brown.

Descanso’s vast botanic collection completely escaped the blaze that took firefighters about 2 hours to extinguish. But the flames devoured virtually all of the Los Angeles County facility’s tools and vehicles—including trams that had ferried visitors around the 160-acre grounds since the early 1960s.

While the trams were part of Descano’s longtime culture, they also were “very large and noisy and intrusive,” unable to deliver people to some of the garden’s most popular but secluded spots, according to Brown. That included the historic Boddy House, with a hilltop setting too challenging for many of Descanso’s elderly, disabled or simply out-of-shape visitors to reach.

In all, Brown said, only 8% of Decanso’s 250,000 annual visitors were boarding the trams, which would sit idle on busy weekends because they were too unwieldy for the garden’s crowded walkways.

In visitor surveys, Brown said, “mobility came up over and over and over again, that it’s not comfortable to walk here.” The fire, he said, “allowed us to rethink the notion of a superior visitor experience.”

Among other upcoming changes, Brown said, the trams will be replaced by electric-powered shuttles—essentially big golf carts—that will transport as many as six passengers into regions previously accessible only by foot. The shuttles will be free and compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act—unlike the $4-a-ride trams.

The timing, Brown said, couldn’t be better. In the months ahead, Descanso will open a 5-acre exhibit in a previously-closed section of the gardens. Promotional materials say the undertaking will replicate and honor the region’s native landscape of oak woodlands, meadows and chaparral—an ecosystem that has been increasingly threatened by aggressive development. The new shuttles, he said, are key in helping the Oak Woodland Project find its audience.

“We wanted to give people access to the further reaches of the gardens,” Brown said, “so they can have a physical experience with a landscape that typified Southern California before it was explored and developed.”

Descanso gardens has long been considered one of Southern California’s premiere public gardens, perhaps best known for its thousands of towering camellias and expansive rose garden. Located in affluent La Canada Flintridge, in the shadow of the San Gabriel Mountains, Descano was founded by E. Manchester Boddy, the former publisher of the Los Angeles Daily News. He sold the property—including his 22-room mansion—to Los Angeles County in 1953.

Brown, the former president of Art Center College of Design, was named executive director of Descanso in 2005 by the Board of Supervisors.

Beyond the trams, he said other vehicles and equipment destroyed in the fire also will be replaced with more efficient, environmentally-friendly versions through insurance, county funding and foundation grants.

Still, everything post-fire isn’t coming up roses—or camellias, as the case may be. Damage from the fire, which apparently was sparked by an electrical problem, has been estimated to be as high as $750,000. And some of the items reduced to ash were priceless—including two old refrigerated boxcars owned by Boddy.

“Mythology holds that Mr. Boddy once used them to ship his camellias to customers in the Midwest and on the East Coast,” Brown said.

But overall, now that the smoke has cleared, the opportunities are clear.

“In a way, the fire was sort of a cleansing experience,” Brown said. “It kind of pulled us together.”

Posted 6/11/14

Bag bans bring parks a holiday gift

April 24, 2014

Griffith Park Maintenance Supervisor Michael Watkins says the bag measures are "definitely working."

As the guy in charge of picking up Griffith Park’s litter, Michael Watkins usually dreads this week.

“Easter is our busiest day of the year, by far,” says the park maintenance supervisor. “We get about ten times the normal amount of garbage. Doing what I do on the week after Easter is like working at Macy’s on Black Friday or being a tax man on April 15.”

This year, however, the bunny left a pleasant surprise for Watkins: a notable reduction in one of his least favorite trash items—single-use plastic bags.

“That bag ban the city passed is definitely working,” he said. “Usually the wind blows them everywhere—up in the trees, along the fence line. This year, there weren’t as many. I can see a huge difference.”

In January, after years of analysis and discussion, the City of Los Angeles became the largest city in the nation to ban plastic bags. The ordinance made the city one of more than 100 California municipalities to outlaw the flimsy, disposable sacks, which can take centuries to decompose, but which are rarely recycled. Used and tossed by the millions, the bags typically end up in landfills after a single use, or blow out onto the streets, storm drains and beaches, where they endanger fish and wildlife.

At the time, opponents of the ban and representatives of the plastic bag industry argued that the bags’ environmental impacts were overblown. But as the area covered by bans has grown to encompass about a third of California’s population, those on the front lines say they’re beginning to see a difference.

A study done in the aftermath of San Jose’s comprehensive 2012 bag ban found that plastic bag litter had dropped by 89 percent in the storm drain system, 60 percent in creeks and rivers and 59 percent in streets and neighborhoods.

“We’ve been seeing a lot less of them, which is good because they’re a real eyesore,” says Shawn Wright, a maintenance worker at Whittier Narrows Recreation Area in unincorporated Los Angeles County, where a county ban on single use plastic bags has been in place since July 2011.

“Of course, there are still some around, blowing into the lakes and onto the fence line, and we still have all the other debris,” Wright said. As usual, he said, it was taking days to clean up the mess left by the tens of thousands of picnickers who had filled—and refilled—the 15-acre park’s trash bins on Sunday.

“The little plastic eggs, the candy wrappers, the confetti, the watermelon rinds, the mango peels, the aluminum foil from the barbeques, the charcoal bags . . . “

Maintenance workers noted one downside to the bag bans: Without plastic bags to fall back on, picnickers seemed to have fewer options to consolidate their trash.

“People would use them to carry, say, their hamburger buns into the park, and then put their empty Coke cans and napkins and whatever into them and toss them when they were finished,” says Rich Cambaliza, a manager for Rich Meier’s Landscaping in Lancaster, which helps maintain El Cariso Community Regional Park in Sylmar. “They were a pain in the butt, but people did have them when the trash cans overflowed.”

And the bag bans have forced picnickers to improvise with leftovers as well, says Steve Dennis, El Cariso’s landscape contract monitor.

“I’ve been seeing people using our Mutt Mitts—the bags we supply here at the park for dog waste—to take home their leftover barbeque or whatever,” says Dennis, laughing that the trick is giving new meaning to the phrase “doggie bag.”

“Hey, they’re clean and right from the manufacturer. I guess you just have to look past what they’re actually supposed to be used for,” he laughed.

At Griffith Park, Watkins says cleanup crews enlisted the public’s help on Sunday, handing out trash bags and asking them to pitch in. By Tuesday afternoon, he said, the cleanup was almost finished—and he had a new candidate for least-favorite garbage.

“If only we could get people to stop using that damned plastic Easter grass,” he said.

Posted 4/24/14

The buses of summer

March 27, 2014

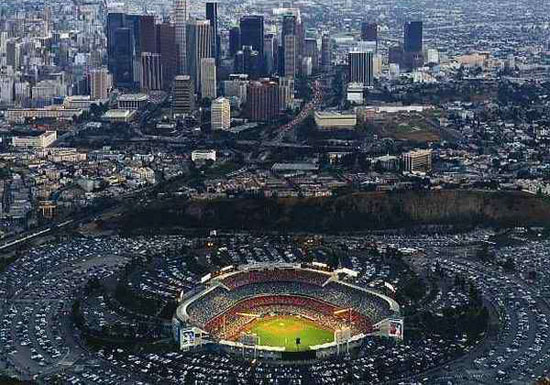

With millions of fans expected to pack Dodger Stadium, traffic planners are swinging for the fences.

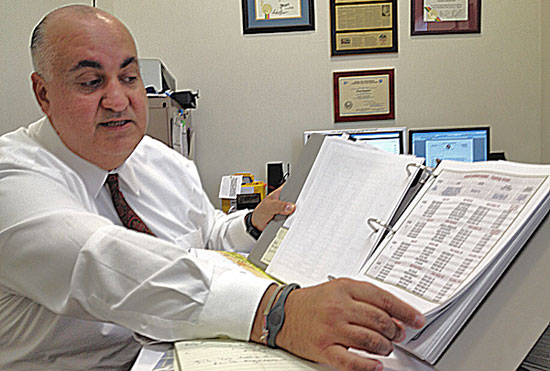

Aram Sahakian doesn’t begrudge the rejuvenated Los Angeles Dodgers their success. But Blue Heaven can mean one helluva headache on his playing field—the city’s streets.

For Sahakian, who oversees special traffic operations for the Los Angeles Department of Transportation, it’s batter up every time there’s a major traffic event in the city. Now, with the L.A. Marathon and the Academy Awards behind him, he’s getting ready for the rush-hour throngs that will wend their way into Dodger Stadium beginning next week.

Although game-day traffic is always heavy around Chavez Ravine, it was particularly challenging last year. Attendance soared to its highest level in seven years—nearly a million above its 2011 low point, when San Francisco Giants fan Brian Stow was brutally beaten in a stadium parking lot in the season’s early weeks. With new owners and a powerhouse lineup that notched an epic winning streak, the Dodgers became one of the hottest tickets in town virtually overnight.

And this year could be even bigger. Sahakian says he’s been told that all but 15 of the team’s 81 home games already have sold at least 40,000 tickets, with tens of thousands more expected to be snapped up as the season progresses.

If baseball is a sport of statistics—batting averages, slugging percentages, RBIs, ERAs and the like—then so, too, is the traffic game. And Sahakian is a student of the stats. He knows, for example, that when the number of cars per hour, per lane, exceeds 1,200, “speed starts slowing down and you get into a gridlock, standstill type of situation.” That string of 40,000-ticket games for this season? He says they’ll easily push the streets beyond their free-flowing capacity, requiring a game plan every bit as nuanced as the one Dodgers skipper Don Mattingly will create for his crew.

To ease the coming crunch, Metro and city transportation officials are urging fans to save themselves some stress—and do their fellow motorists a favor—by ride-sharing or hopping aboard the Dodger Stadium Express bus, which leaves Union Station every 5 to 10 minutes, beginning 90 minutes before the game and continuing through the 3rd inning. The ride is free for ticket holders.

The express buses have been running for four seasons, but last year they scored their highest ridership yet, jumping from 136,000 passengers to 186,000. “Obviously,” Sahakian says, “we want to double that, if not triple it, this year.”

Last year, the route included for the first time a 1.5-mile dedicated bus lane along Sunset Boulevard. If more people continue to ride the express, Sahakian says, then traffic should ease for commuters struggling to get home along Sunset’s main lanes, which frequently were bumper to bumper from downtown to the stadium.

This year, Sahakian says, he also was determined to fix what he saw as a traffic and safety issue—the use of orange cones to keep vehicles out of the newly-designated Dodger express bus lane. Not only were buses “knocking cones all over the place,” he says, but transportation workers were “putting themselves in harm’s way” by setting them up with cars whizzing past. The cones also made it difficult, he says, for police to pull violators out of the bus lanes without a nearby side street or a break in the cone line.

So instead of the cones, Sahakian says, what he really wanted was a stripe on the pavement—“and I said I wanted it immediately.” And that, in turn, would end up giving L.A. cyclists a much-needed gift in the process.

Sahakian’s inquiries led to the discovery that the city’s bicycle master plan called for a lane to be painted along that same stretch of Sunset Boulevard at some point in the future—a time frame that was accelerated to create a combination year-round bus and bike lane during peak traffic hours.

The Dodger Stadium Express buses, however, are just one facet of a broad push to ease ballpark congestion. Among other things, a bus/bike lane has now also been painted on eastbound Sunset Boulevard to facilitate the post-game flow. What’s more, another stadium entrance, at Scott Street, will be opened to help reduce congestion, despite complaints from Echo Park residents who worry that the increased traffic will bring problems to their neighborhood.

Sahakian acknowledges that reopening the Scott Avenue gate “is a very sensitive issue.” But he insists that the city is working hard to avert problems with a plan to route vehicles around residential neighborhoods, increase the number of traffic control officers and create a locals-only preferential parking district.

But no matter how many traffic mitigation measures are undertaken, Sahakian says, there’s really nothing that can be done about the biggest one, a truism of L.A. fandom. “It’s not a secret that Angelenos,” he says knowingly, “don’t plan on getting to any sporting event early enough to avoid traffic.”

Posted 3/27/14

Market’s got a brand new bag

October 15, 2013

Attention, Grand Park shoppers: plastic bags are no longer on the menu at your weekly farmer’s market.

On Tuesday, merchants started handing out paper bags with purchases, and park employees distributed more than a hundred free, reusable tote bags to shoppers who agreed to fill out a short, six-item questionnaire about their market experience.

“We ran out in the first two hours,” said Karen Tran, one of two workers handing out the totes.

The market’s manager, Susan Hutchinson, said some merchants had initially expressed concerns that paper bags would be more expensive than plastic and would not hold up as well to potentially messy items, like ripe peaches and plums.

Both fears proved to be unfounded when vendors transitioned from Styrofoam clamshell containers to cardboard, and she expects an equally smooth transition to the new bags, which are required under county law and will be mandated by the city as well beginning Jan. 1, Hutchinson said.

“The reality is it’s not such a big deal,” Hutchinson said. “People adapt.” She’s hoping that customers’ adaptation will include remembering to bring their own reusable bags to the market, which runs from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. on Tuesdays.

On Day 1, the lunch time crowd seemed to welcome the change.

“I think it’s great,” said county employee Nyla Jefferson, carrying two paper bags loaded with apples, peaches, plums and blueberries.

LAPD Detective Ron Walker held one of the free tote bags as he waited for his apple feta salad to be prepared. He said he was glad to see the bag policy change.

“Even supermarkets are charging for bags now,” he said.

Posted 10/15/13

Love on the beach

September 18, 2013

From cigarette butts to lottery tickets, you never know what you’ll find at the International Coastal Cleanup. Eveline Bravo and Olga Ayala, for instance, found love.

It was 2007, and Bravo, brand new in her job as Heal the Bay’s beach programs manager, was recruiting site captains for the worldwide volunteer day, which this year takes place on Saturday.

Ayala was enlisted to help with the effort—the second year in a row that she had been called upon to round up volunteer trash-pickers.

At first, neither was particularly enamored of the other.

“The year before, and I kid you not, they had called me just one weekend prior,” Ayala remembers. “And I had dropped everything and done everything in my power to help them, but only about 15 people showed up.

“So this time, I was thinking ‘Maps, geographic zones, resources, highlighters—I’m gonna show them how you do this.’ And she was, like, ‘Uh, that sounds great, but actually, here’s how we’re going to do it.’ ”

“We clashed,” Bravo says, laughing. “I wanted to do my job my way.”

For months after that first meeting, their relationship remained frosty, even though Ayala—secretly impressed by the competence of the 10-years-younger Bravo—mustered hundreds of volunteers and broke a Heal the Bay record that year with the tonnage of trash they retrieved from their assigned cleanup site, a Panorama City park. (Cleanups in inland areas are a large part of the beach initiative because everything that gets into local waterways ends up in the ocean.)

With time, however, the ice melted. “She became like a challenge to me,” says Ayala. “I was like, ‘I’m nice, and you’re gonna like me.’ ” Bravo, meanwhile, says she began to do some soul searching.

“My New Year’s resolution that year had been to be nicer to people, and for some reason, as I made it, my thoughts went to her. So I sent her an email and a few months after that, we went out dancing. And somebody at the club asked me, ‘Are you two together?’ And after I said yes, I realized that she hadn’t been asking if we had come there together.

“So I looked at Olga and said, ‘I think we just told that girl that we’re together together. And she said, ‘Do you want to be?’ ”

The two became a couple, bound in part by the gifts that had drawn them to public service.

“I admire hardworking people who know what they’re doing,” says Ayala, who at the time she met Bravo was a field deputy to then-Los Angeles City Councilman Tony Cardenas. “And she was so hardworking, and straightforward, and kind, and beautiful—I fell in love.”

For Bravo, Ayala’s open heart was a revelation.

“As we became friends, I realized how pure and genuine she is—nothing bad ever comes out of her brain. I thought that people like that didn’t exist, but somebody can be mean or poor-spirited or a bad influence, and Olga just won’t see it. She never judges. Her heart is just genuinely into doing the right thing.”

In 2010, the bond deepened: Bravo was diagnosed with cancer and they discovered how much harder an ordeal like that could be for gay and lesbian couples, who lacked the legal protections that straight, married people took for granted. After her treatment, Bravo says, they made a pact to throw all their leftover energy and expertise into the marriage equality movement.

“We had to make all these hard decisions and go through surgery and get legal permission for Olga to be in the hospital with me,” says Bravo. “We decided that we needed our rights.”

So last month, a scant six weeks after the courts officially re-opened the doors for same-sex marriage in California, the two were wed in Calabasas by Ayala’s ex-boss Cardenas, who was elected to Congress, representing the San Fernando Valley’s 29th District, in 2012.

Now they live in mid-city Los Angeles with their cocker spaniel Sparky. And on Saturday, you’ll find them at this year’s Coastal Cleanup, picking up trash—together—at the Santa Monica Pier.

Posted 9/18/13

From museum gardener, seeds of change

April 4, 2013

Florence Nishida's Natural History Museum class has sprouted gardens all over L.A. Photo/Gordon Hendler

For some, spring is a chance to plant a few tomatoes. For Florence Nishida, it’s an opportunity to re-landscape the face of Greater L.A.

This month, for example, the 75-year-old master gardener will be checking in on some of the 20 or so South Los Angeles yards she helped turn into vegetable gardens. She’ll be sizing up a front lawn and a parkway for makeovers by Los Angeles Green Grounds, the urban gardening group she co-founded.

She’ll be monitoring the community garden she recently did in Koreatown for the new First 5 initiative, Little Green Fingers, and following up with the Los Angeles Conservation Corps on the raised beds she devised for outside their East L.A. office. Then there’s the LA Green Grounds table to set up and man for Earth Day at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, not to mention the regular Sunday gardening workshops she conducts at the museum.

And this is the former schoolteacher’s idea of retirement.

“From years and years ago, it has been my goal,” explains Nishida, “to have a vegetable garden and a fruit tree on every block in L.A.”

Nishida isn’t the only urban gardener on a mission these days in Los Angeles County, but lately, she has been among the more productive ones. Since 2010, when she persuaded the Natural History Museum to let her install a small teaching garden on its Exposition Park campus as part of an inner-city community project, her green thumb has been in many, if not most, of the urban gardening projects that have sprouted across the city like backyard zucchini.

One of her first students, artist Ron Finley, has won international acclaim with a pair of TED talks on urban gardening. Her former teaching assistant, the museum’s public programs manager Vanessa Vobis, is among at least five protégés who have gone on to become fellow master gardeners. Green Grounds, which she co-founded with Finley and Vobis, has literally broken new ground in South L.A., where the group has worked one yard at a time, installing gardens at volunteer “dig-ins” to help under-served neighborhoods grow their own organic produce.

Nishida herself has been called in increasingly to consult on community gardening projects throughout the county. Meanwhile, her edible garden at the Natural History Museum has drawn some 150 students just to the beginner’s workshop; this year, her class will expand to the new Erika J. Glazer Family Edible Garden, a showplace of fruit trees and seasonal plantings that will open officially in June with the rest of the museum’s new Nature Gardens.

“The museum was ground zero,” Nishida says now. “It all started from that class.”

Nishida hasn’t always seen gardening as a road to anyone’s revolution. A native Angeleno, she says, home gardens were a fact of life for her Japanese-American relatives throughout Southern California and in the Exposition Park neighborhood where she grew up.

“After World War II, my grandparents resettled in West L.A. near Sawtelle and grew vegetables in their front yard, as did a lot of people,” she remembers. But as time passed and L.A.’s economy shifted, fast food joints, un-walkable streets and dense apartments crowded out the kitchen gardens and mom-and-pop produce stands, gradually eroding the city’s health and turning organic produce into an upper-middle-class status symbol.

As Nishida moved to Topanga, worked and raised her four children, she says, she always held a notion that her old, blighted neighborhood might be restored if someone could bring back the green space. Eventually—after 20 years as an English teacher in the Los Angeles Unified School District, another 20 as a bureau manager and research librarian at People magazine’s West Coast Bureau and a graduate degree in botany that resulted in a sideline as a mushroom expert at the Natural History Museum—she decided to revisit her old theory.

“I had seen a little article in the Los Angeles Times about the master gardening program at the UC Cooperative Extension,” she remembers. “It was a tiny little article, but for whatever reason, I just saved it.” When she retired in 2008, she says, she took the classes, which require, among other things, that graduates go on to lead community gardening projects in under-served parts of their cities; one of her early projects was a home garden that later served as a model for Green Grounds. Another was a plan to bring gardening knowledge to Exposition Park by launching a class at the museum.

That idea—which dovetailed with the museum’s centennial plans to re-landscape its North Campus into a “living laboratory”—led to her meeting with Finley, an experienced gardener in his own right who had signed up for her class after he had noticed another master gardener’s project near Dorsey High School. Soon Nishida was asking Finley for advice on how to bring more neighborhood people into her museum classes.

“I told her, ‘They’re not gonna come to your classes—they got Burger King, they got Kentucky Fried Chicken’,” recalls Finley. “We gotta take it to them.” That, he says, was the start of Green Grounds, which effectively installs free gardens in people’s front yards in the style of an old-fashioned barn raising, and which has taken off since Finley’s second TED talk in February.

“We got people driving in from Ventura,” he marvels. “I’m like, damn! Is it that boring in Ventura? I mean, we had over 300 people sign up at our last dig-in, and all we needed was 15.”

Nishida says Green Grounds has been an education, not only in the art of managing volunteerism but on the laws of nature in L.A. Their first garden flourished for three months, only to be destroyed by the homeowner’s German shepherd. Another garden fed a family for nearly half a year before they were evicted. A third fell prey to a local gang she’d never heard of—gophers. Finley famously fought with the City of L.A. over the parkway he wanted to replant outside his house.

Nonetheless, Nishida says, 13 of the Green Grounds gardens are still blooming, with more in the pipeline; recently the group set up a fiscal sponsorship with the L.A. Community Garden Council to handle the influx of donations since Finley’s TED talks. And those gardens have, in turn, been change agents: Neighbors have gotten to know each other over samples of fresh produce, she says, and exercise groups have sprung up among dig-in volunteers and recipients of gardens.

In fact, she says, her only disappointments have been that the movement hasn’t spread faster, and that her commitments have left her so little time to tend to her own yard.

“Oh, it’s awful,” she confesses, laughing. “My vegetable beds are overrun with weeds.”

Posted 4/4/13

Bug fare at the Bug Fair

May 16, 2012

David George Gordon, who won last year's bug cookoff, is an ardent advocate of insect cuisine. Photo/Time

Fancy yourself an adventurous eater? The county’s Natural History Museum has something to challenge your palate at the 26th annual Bug Fair. That’s right—it’s time to grub on grubs.

The “Bug Chef Cook-Off” debuted at last year’s fair, and it’s back again in 2012 by popular demand. Three of the top entomophagists (bug chefs) from across the country are ready to go antenna to antenna with their best bug dishes.

They’re part of a burgeoning bug cuisine movement that’s grabbed the attention of publications including Time and The New Yorker, which have chronicled the efforts of those seeking to make insects palatable as human food for a variety of environmental, ethical and economic reasons.

One of the movement’s stars, David George Gordon, won last year’s cook-off at the museum with tempura-battered tarantula and teriyaki grasshoppers on rice noodles. Gordon, 62, an ardent bug consumption advocate, said hosting the cook-off is a very progressive move by the museum.

“In the United States and Europe it is an uphill struggle,” said Gordon. “Europeans have a bad attitude about bugs. But meat is basically muscle, whether from a tarantula or a cow. Tarantula has a similar texture to crab.”

Gordon, a science writer in the process of updating his Eat a Bug Cookbook, said a trip to Switzerland inspired him to add fondue to this year’s menu (think decadent, chocolate-dipped locusts).

Daniella Martin, the brains behind the Girl Meets Bug blog, is on her own mission to bring critter cuisine to the public. Her YouTube videos offer step-by-step instructions on how to cook and eat things like wax worm tacos and fried scorpion.

The third contestant is David Gracer, 47, of Rhode Island. He is the founder of Small Stock Foods, a company that arranges educational programs, bug tastings, bug catering and bug food sales. He has appeared on “The Colbert Report” and the “Tyra Banks Show” to promote human consumption of bugs. According to Gracer, the reasons to eat insects are both environmental and culinary.

“It’s a good way of dealing with overpopulation by conserving our water and food resources,” said Gracer. “On the other hand, there is also the adventure and fun of eating something new. When you eat insects you are eating closer to nature.”

Gracer’s dishes will feature wax worms, Ugandan katydids (“surprisingly rich, they taste a lot like crispy French fries”) and a surprise ingredient—maybe giant ants, he said.

In addition to competition dishes, the chefs plan on providing courageous attendees with free samples, like Gordon’s famous Chirpy Chex Party Mix. (The “chirpy” part, as you may have guessed, is roasted crickets.)

The Bug Fair, which bills itself as the biggest bug festival in North America, will provide plenty of other entertainment, too—entertainment that doesn’t involve eating or watching other people eat bugs.

The theme for Bug Fair 2012 is the “Year of the Fly,” and if that conjures thoughts of biting horseflies or pesky gnats, museum curator of entomology Dr. Brian Brown wants a chance to change your perspective.

“A few bad apples like mosquitoes that have ruined our thinking about flies,” said Brown. “Most are neutral or beneficial to humans.”

For example, Brown will be presenting “flower flies,” which look a lot like wasps or bees. Brown said flower flies are important pollinators that also feast on aphids— the small, plant-devouring pests that are the bane of gardeners everywhere. Brown also said the flies are a popular subject for amateur naturalists who have moved beyond the most popular species like birds and butterflies.

Other attractions at the event include bug pinning demonstrations, bug-sniffing dogs, specimen handling opportunities and “Supersized Insect Walkabouts”—costumed performances that include a giant monarch butterfly on stilts. The museum and its insect exhibits will also be on display, along with a related special exhibition of jewel-encrusted butterfly brooches in the Gem and Mineral Hall.

The Bug Fair runs from 9:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. on Saturday, May 19, and Sunday, May 20. Tickets are $12 for adults, $9 for seniors and students, $8 for youth ages 13 to 17 and $5 for children ages 5 to 12. Kids under 5 are free. Parking is $8 or $10 in adjacent lots, but attendees may opt to try Metro’s new Expo Line, which has two stops just a short walk from the museum.

Out of the frying pan and into the belly? Maybe, if the eating public decides that bugs are food. Photo/Time

Posted 5/16/12

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink