Fresh start for failed youth camp school

November 4, 2010

Less than a year after a class action lawsuit alleged a near-total breakdown in the school system at the county’s largest juvenile detention camp, the Board of Supervisors has approved a far-reaching settlement that will overhaul educational services at the Challenger Memorial Youth Center in Lancaster.

Under the agreement negotiated with a coalition of civil rights groups and approved Wednesday, the complex of six probation camps colloquially known as “Camp Challenger” will have up to a year to vastly upgrade an educational system that has been beset for several years by accusations of incompetence and disregard.

Among other things, the camp, which is required by law to provide schooling to some 650 students, will be forced to hire reading specialists and create vocational and literacy programs for its charges, many of whom arrive with reading skills that are several years behind grade level. Also among the mandates are improvements in access to books and workspaces, a designated classroom for kids in the facility’s special handling unit, an updated security system and improved monitoring of teacher absences.

A panel of nationally-known educational experts will develop and monitor the reforms at the institution. Intensive tutoring also will be made available to students who were at Challenger after 2008, the parties said.

“Los Angeles is going to be a national model,” said Mark Rosenbaum, chief counsel of the ACLU of Southern California, which brought the class action along with Public Counsel and the Disability Rights Legal Center on behalf of three youths who had been held at Challenger as minors.

“While we do not acknowledge that all the allegations are true, we did recognize there were some serious problems and this lawsuit brought it to everyone’s attention,” agreed Assistant County Counsel Roger Granbo, who negotiated on behalf of the county. “There’s going to be a complete culture change out at Challenger.”

The suit, filed in January against the probation department and the Los Angeles County Office of Education, had depicted educational negligence at Challenger in epic proportions—a years-long situation in which teachers were routinely AWOL, kids lacked textbooks, pleas for educational help were ignored or punished and at least one teenager who had been at Challenger for most of his adolescence was awarded a diploma, even though he was illiterate.

One teenager allegedly spent months in a solitary cell with no schooling except for occasional meetings with a teacher who sometimes left after as little as 15 minutes. Classwork, the suit claimed, consisted of occasional worksheets thrown under the cell door. Another said he was denied special instruction even though, at 17, he had the reading comprehension of a second grader and had repeatedly told his teachers he didn’t understand the classwork.

The suit alleged that students were so illiterate that they could not complete job applications or read restaurant menus. “These kids were regarded as disposable people,” Rosenbaum says.

Situated in the desert next to a prison, the Challenger complex has suffered from its remote location, as well as architecture that imparts a forbidding, prison-like atmosphere, even without the punitive culture and hostility that have plagued it in recent years, educational experts say. Allegations of mistreated teenagers there made it the target of a Department of Justice investigation, and a 2009 Los Angeles County Probation Commission report called its school system “broken.”

However, both sides said, the settlement promises to address longstanding concerns in and outside the probation system, and retirements and resignations in recent months have turned over leadership at both the county probation department and the office of education.

“Already we’re seeing changes at Challenger,” said Cal Remington, chief deputy of the probation department. “There’s a new principal I have a lot of confidence in, and he’s already making a difference. And we’ve already brought in some experienced teachers from other institutions.”

Rosenbaum praised the county for seizing on the lawsuit as an opportunity to push for more change. “This was a cooperative venture from the beginning — all the energy was toward finding a solution for the kids,” he said.

And experts in the rehabilitation of juvenile offenders said that even at an institution like Challenger, teachers and programs can make a difference.

“You can blame the kids, you can blame the architecture, you can say the place is in the desert far from home,” said University of Maryland education professor Peter Leone.

“But I’ve seen some correctional settings that were really unappealing and they have some terrific programs. Look, we’re the adults in this situation. If we teach kids begrudgingly and don’t inspire within them the spark of learning, we have no one to blame but ourselves.”

Although the county and the ACLU have agreed to the settlement, it will not be finalized until the court signs off.

Posted 11/4/10

Touring Hall of Justice, by flashlight

November 3, 2010

The temperature outside was pushing 90, but when the padlock came off the chained doors of the Hall of Justice, the air rushed out like a chilly blast from the crypt.

Inside, though, the legendary 1925 building looks like it’s starting to wake up from its big sleep.

The Hall of Justice—where Charles Manson, Bugsy Siegel, Sirhan Sirhan and a host of other big- and small-time criminals once cooled their heels, where Marilyn Monroe’s body ended up after her suicide and where Robert Mitchum once did time for marijuana possession—is one of downtown’s Los Angeles’ most striking landmarks.

Red-tagged and vacant since the 1994 Northridge earthquake, the Hall not so long ago was rat-infested, debris-ridden and home to the occasional transient.

Now its interior has been cleaned out and virtually gutted.

Later this month, the county Board of Supervisors will be asked to approve the selection of a firm to undertake the historic rehabilitation and retrofitting that will turn the site into the new headquarters for the Sheriff’s Department. Staff from the District Attorney, Public Defender and Alternate Public Defender also will be stationed in the building, located at Spring and Temple, across from the criminal courts building.

Work on the three-year project is expected to begin early next year. The approximately $244 million Hall of Justice rehabilitation, along with other capital projects, will be funded in part by “Build America” bonds whose issuance was approved by supervisors on Wednesday. The project’s cost is expected to be partly offset by lease savings for the departments that will be relocating to the building.

Alicia Ramos, who has been overseeing the Hall of Justice project for the county Department of Public Works since 2004, said that years of advance work have been devoted to “trying to create the cleanest slate we can” for the new office space interior.

On Tuesday, Ramos led a writer for Supervisor Yaroslavsky’s website and a county photographer on a flashlight-illuminated tour that started in the building’s basement and ended on its rooftop. A gallery of photos from the tour, below, offers an unusual glimpse inside the building as it awaits its transformation.

To get to this point, tons of debris—including about a half million dollars’ worth of recycled jail cell bars—have been hauled away and reams of once-confidential documents have been incinerated and sent to that great repository in the sky. (See update below.) Elevator shafts now stand empty, their vintage wood-and-brass cabs sidelined until they can be pressed back into service with a modern operating system.

All of the building’s jail cells have been ripped out. One cell block, said to have housed Manson, has been preserved and relocated to the first floor, where it eventually will be opened to the public as part of a new museum/interactive center focused on the history of the building and the sheriff’s department.

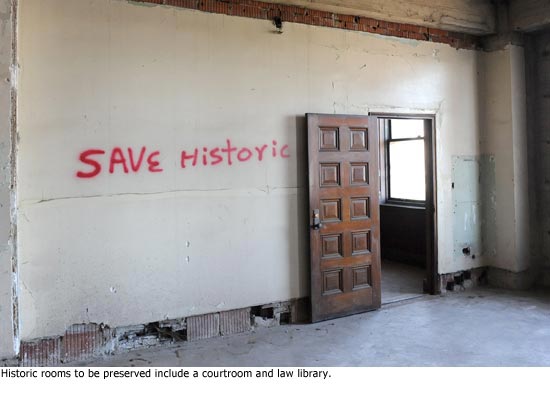

The building’s courtrooms, once the site of trials that included the Sleepy Lagoon murder case, have all been demolished except for one, which is being preserved right down to its embellished plaster corbels and will be restored and used as a sheriff’s conference room. The same goes for a wood-paneled law library nearby. Both are located on the building’s 8th floor, where the sheriff will have his office.

The plan to bring the Hall of Justice back to life includes seismic reinforcement; new electrical, plumbing and mechanical systems; a 1st floor cafeteria that will be open to the public; and a nine-level, 1,000-vehicle parking structure, half of it underground.

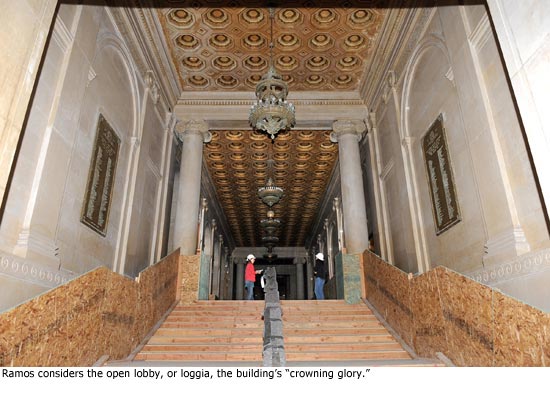

The building’s open lobby, or loggia—which Ramos calls “the crowning glory of the Hall of Justice’—also is awaiting restoration. Even in its current state, the loggia exudes glamour and gravitas, from its marble columns to its elaborate ceiling and chandeliers. Covered up for the moment are its terrazzo floors and historic iron-and-brass stairs.

“It’s dramatic. It’s the scale, it’s the materials,” said Ramos, 37, an architect and Cal Poly Pomona grad. “It really can take you back to a period.”

Even in its current state, the Hall—whose architectural style is variously described as Beaux Arts, Italian Renaissance or Federalist—holds no terrors for Ramos, despite its sometimes macabre past.

“I haven’t gotten any ghost stories out of this building,” she said. Those she’s heard from others can be logically explained. (Voices in the basement, for instance, are more likely coming via a closed-up tunnel from an adjoining county building, not from the spirit world beyond.)

“They’re all stories to me. I’ve never seen anything wicked or sinister,” Ramos said.

She even ventured inside the Hall alone occasionally, like the time she came inside to photograph a judicial seal inside the law library.

Later, she was there when a transient who’d been caught living in the building was escorted away by police.

The man looked at Ramos. “He said, ‘I know you. I’ve seen you walking through here.’ The hair went up on my neck.”

Nowadays, she said, “I don’t go through the building by myself.”

Up on the building’s roof—once a prison yard-style exercise area for inmates that may be turned into a jogging track for employees—Ramos reflected on everyone and everything these walls have seen.

“Between Marilyn Monroe and Charlie Manson,” she said, “it’s kind of the good and the bad that come through these kinds of facilities.”

Photos by Scott Harms/Los Angeles County

Posted 11/3/10

Updated 11/4: Regarding questions about the destruction of documents, sheriff’s officials said Thursday that they removed all records from the Hall of Justice and left behind only trash or outdated forms. Department of Public Works officials said they exercised an abundance of caution and treated all papers left behind as confidential because they were not in a position to evaluate them. They said all documents were destroyed in accordance with the county’s policy.

DCFS data collection called “colossal mess”

November 3, 2010

Two weeks ago, in an effort to find possible trends in the tragic deaths of youngsters who’d come to the attention of Los Angeles County child welfare officials, the Board of Supervisors asked for data on fatalities dating back two decades.

.

On Wednesday, however, a clearly angry Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky said the board would be lucky to get useful information from just two years ago, calling the data collection efforts of the Department of Children and Family Services “a colossal mess.”

Yaroslavsky said the Chief Executive Office has expressed concerns that the historical information may not even be available. This, Yaroslavsky said, “begs the question: What is the Department of Children and Family Services basing any of its policies on when it comes to protecting children’s lives?”

The supervisor’s remarks came during yet another debate—and more motions—involving the performance of DCFS, which has come under withering criticism in the wake of numerous child deaths and the department’s failure to publicly disclose some of them.

One of the motions, approved by the board during its Wednesday meeting, called for a single county entity to track and compile information on child deaths related to abuse or neglect. Another motion called for the reversal of the board’s earlier request for 20 years of fatality data in the belief that it’s better to look forward than back.

But the board majority disagreed. Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, who had co-authored the motion for historical information with colleague Michael D. Antonovich, said that without such data, “the best you do is find yourself being driven by the anecdotal rather than analytical.”

Acting on a compromise suggested by Yaroslavsky, the board scaled back its request to10 years. Although the department may be unable to generate even that data, Yaroslavsky said, the effort should still be aggressively pursued in the spirit of transparency for a public that “is livid” with the county, from the top down.

If the information isn’t available, then “the public ought to know that the Department of Children and Family Services can’t respond to that kind of fundamental question,” he said. “But to just pull out and say, ‘Never mind. We don’t really want to do that,’ is not the way I want to do business.”

He added: “I think we should stop being defensive about this and just let the chips fall where they may.”

Posted 11/3/10

State wins billions in needed federal health aid

November 3, 2010

After more than a year of tortuous negotiations between state and federal health officials, it was announced this week that California will receive $10 billion in health aid during the next five years through the renewal of its ongoing Medicaid waiver.

After more than a year of tortuous negotiations between state and federal health officials, it was announced this week that California will receive $10 billion in health aid during the next five years through the renewal of its ongoing Medicaid waiver.

The infusion of new federal funding will expand health coverage for uninsured low-income residents, improve access and quality of care for seniors and the disabled, and help implement federal health care reform when its new rules take effect in 2014.

The negotiations took place between the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services and California’s Department of Health and Human Services.

The County of Los Angeles—constituting roughly 30% of the state’s population but 34% of the state’s medically indigent and 36% of those living below the federal poverty level—will be a major beneficiary of the aid. Those funds have helped to underwrite the County’s continuing reform and restructuring efforts since 1995, when the Clinton Administration granted the initial five-year federal waiver under Section 1115(a) of the Social Security Act.

That waiver allowed Los Angeles County to reconfigure its health-care services, creating public-private partnerships with non-profit community-based clinics and expanding ambulatory and outpatient services with federal money. This was accomplished by “waiving” federal requirements that had restricted the funding to reimbursement for in-patient hospital services, the costliest type of medical care.

To learn more about the recently approved agreement, formally known as California’s “Bridge to Reform: A Section 1115 Waiver Proposal,” visit the California Department of Health Care Services site here.

Posted 11/03/10

Changing of the guard at Watts Towers

November 3, 2010

Minding a masterpiece isn’t easy. The Watts Towers have been among Los Angeles’ great public treasures, but their upkeep has been a full-time challenge almost since they were finished in 1954.

Rattled by earthquakes, assaulted by rainstorms, the fantastic, filigreed metropolis erected by an Italian-born amateur stonemason in a South-Central barrio is perpetually in a state of deterioration. The mortar cracks. The tiles are forever falling. The joints are damp with seepage and rusting from within.

Late last month, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art announced plans to lend a hand to the recession-slammed city in ensuring that Simon Rodia’s renowned public sculpture is preserved. The art world is applauding the one-year agreement, in which LACMA will contribute expertise, staff and — most crucially — fundraising assistance.

And cheering the loudest are Zuleyma Aguirre and Virginia Kazor.

For some 20 years, Aguirre and Kazor have tended the towers. Before her retirement this summer, Kazor spent 19 years as the historic site curator, managing the conservation effort for the city’s cultural affairs department. Aguirre, her lead conservator, handled all the on-site restoration, tending every inch of concrete, tile and metal until she was sidelined two years ago by an injury on the job.

For some 20 years, Aguirre and Kazor have tended the towers. Before her retirement this summer, Kazor spent 19 years as the historic site curator, managing the conservation effort for the city’s cultural affairs department. Aguirre, her lead conservator, handled all the on-site restoration, tending every inch of concrete, tile and metal until she was sidelined two years ago by an injury on the job.

Together, the two women – one an art historian raised in Los Angeles, the other an El Salvador-born expert in the restoration of pre-Columbian artifacts – have shepherded the landmark through the Los Angeles riots, the Northridge earthquake and countless storms and budget woes. This week, they sat down with ZevWeb to talk about the labor of love that became not only Simon Rodia’s life’s work, but theirs as well.

“The first time I came to the towers,” Aguirre remembers, “it was 1988. They were just – oh! Amazing! Rodia’s work made me feel like I really had not done too much in the world.”

She had come to the United States in the early ‘80s on a grant to visit museums, and remained, reluctant to return to her country’s civil war. The Watts job became hers after she hired on with a city consultant working on the towers’ preservation. The project, she immediately realized, would be like no other.

“I had come from working in museums,” she says, “and the towers were just so different. There were no drawings we could find, no blueprints. We had to do X-rays to learn how he did the connections on 5,000 joints.”

“I had come from working in museums,” she says, “and the towers were just so different. There were no drawings we could find, no blueprints. We had to do X-rays to learn how he did the connections on 5,000 joints.”

In 1991, Kazor became Aguirre’s supervisor on the project. Already a longtime curator for the city, her relationship with the towers was more than three decades old. As a student in 1958 at the University of Southern California, she had been assigned to report on them by her design teacher.

“I was so fascinated that after that, when I met someone and found him interesting, I’d always take him first to the Watts Towers,” she remembers, laughing. “And if — and only if — they liked them, then I’d go out with them.”

Then and now, she says, she was moved by the assemblage – a collection of 17 structures, built over 33 years by an eccentric handyman. Constructed by hand out of scraps and castoffs, the towers’ famed spires soar up to 99 feet over their impoverished surroundings.

Kazor, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s shortly after being assigned to Rodia’s project, connected with the resolve that fueled it: “They’re ours and they’re absolutely unique. And they are a testament to what one person can accomplish, if they just set their minds to it.”

That determination, the women say, was what most impressed them, day after workday.

“Rodia was a common laborer who took part-time jobs,” Kazor says, “but he was sort of intuitively brilliant. He took any steel he could find — rebar if it was available, but he’d use water pipe or anything he thought would work.

“And he didn’t weld. He overlapped the pieces, wrapped the overlapped portion with wire to hold them together, and then covered that with chicken wire. Then he took a very dry concrete mix — you could pick it up by the handful and it would hold its shape — and he’d press that into the chicken wire. Then he would press into that the decorative elements he had chosen. Seashells or tile or the impression of a tool or broken glass.”

But his work didn’t end there. “After that, he would have to keep the concrete moist by spraying it with water for more than a week,” Kazor says. “And he did this by climbing up the towers as if they were scaffolding. And he would carry on his arm a bucket with whatever materials he needed. And every time he needed more materials, he had to go all the way back down to the ground and then all the way back up again.”

Honoring that artistic commitment has required its own brand of determination. After every Santa Ana wind or winter rainstorm, tile and bits of concrete shower from the structures onto the ground. Moisture is a constant challenge.

“Once water gets past the decorative surface and through the concrete, the steel inside it rusts,” says Kazor. “And then the rust expands. And the cracks get larger, and more water gets in, and eventually the interior steel structure rusts away.”

Part of Aguirre’s job, she says, was to walk the site with her crew daily, picking up fragments and carefully documenting where they had fallen and where they belonged.

“Early on in the project, the whole structure was completely photographed, and broken down into a 4-foot grid,” says Kazor. “So each worker, every day, would be assigned a certain area, and at the end of the day, record what he did there.”

That painstaking documentation, she says, has been the key to FEMA and other grants that have underwritten tower restoration again and again.

The work hasn’t always been safe.

“Once,” Kazor says, “one of our construction workers was on the scaffolding 40 feet in the air, and an earthquake hit. And he said, ‘Please don’t fire me, but the scaffolding was shaking so hard, I had to hang onto the tower.’ When he looked down, he said, he could see the wave of the earthquake come down the street, lifting the backs of the parked cars.”

In fact, Aguirre has been unable to work for more than two years, after having been struck by a piece of scaffolding that damaged two cervical vertebrae in 2008. It was not her first on-the-job injury. In 2001, she says, she was mugged as she arrived for work early one morning, carrying her purse and her laptop.

“This young fellow asked me for the time, and when I didn’t know, he went with his fist in my face,” Aguirre remembers. The blow broke six of her teeth and severed an artery, and Kazor says Aguirre nearly bled to death before she was found.

Yet for all the challenges, the women say, the towers have been deeply rewarding.

“It’s magic there,” says Aguirre. “I felt I could hear Rodia’s steps some days, when everybody went to lunch and I stayed there alone. From the top, you can see all over the city. It’s gorgeous. You have a whole other vision of Watts. Or just sitting there below, looking up. Hearing all the Watts sounds. The neighbor sounds – the rap, the Mexican music, the lambada, the smell of the materials. The mix. Everywhere you look, it is art.”

This fragile, unconventional beauty, Kazor says, is why LACMA’s involvement is so welcome.

“The city does not really have the resources any more to do what needs to be done,” she says, noting that by the time she retired, the manpower the city had committed to the towers had fallen from about 14 full- and part-time workers to two.

“The Watts Towers are as important as any work in a museum. They are like the Eiffel Tower, or the Millennium Wheel in London. They’re a great gift to Los Angeles.”

Watch this short film on the Towers

Posted 10/28/10

Check for the latest closure information

Check for the latest closure information