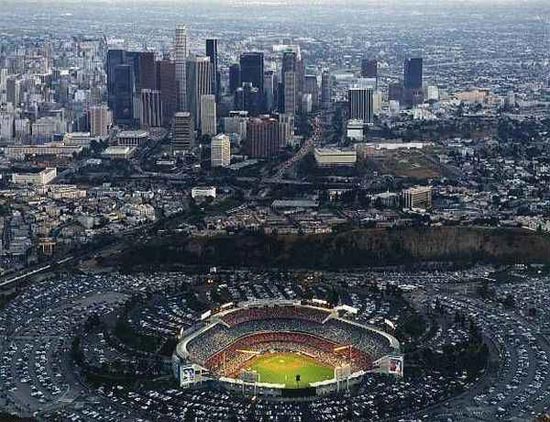

Bus me out to the ballgame

March 23, 2011

Don’t get beaned by traffic this baseball season—take the Dodger Stadium Express.

Metro is providing direct bus service from Union Station to Dodger Stadium beginning with the March 28 preseason matchup with the Anaheim Angels and continuing through all 81 home games (we won’t jinx the playoffs just yet).

Game and season ticket holders ride for free; all others pay $1.50 each way. Rides will depart every 10 minutes in the 90 minutes pre-game, and every 30 minutes throughout the game and for 45 minutes after the final out.

The Dodger Stadium Express, now in its second year, is funded by the Mobile Source Air Pollution Review Committee (MSRC), a group dedicated to reducing motor vehicle air pollution along the SoCal coast.

New to the program this year, Metrolink is providing special late trains for night games. They depart from Union Station at 11 p.m. to Ventura County, San Bernardino County, and the Antelope Valley. The cost of the Metrolink trains ranges from $8 to $10 depending on how far you need to go.

Take the express bus on game day and you will save on parking as well as gas. General parking at the Stadium starts at $15 per car. Consider planning your whole excursion with Metro so you can focus on other things, like how you’re going to digest all those Dodger Dogs.

Posted 3/24/11

Calling all junior nature lovers

March 22, 2011

Will kids go wild for a machine that mimics the mouth of a pill bug? How durable should a soil sifter be if you want it to last for more than a field trip or two? Will people examine a compost pile without an invitation?

Inquiring minds at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County want to know.

In less than a month, the museum’s wildly popular Butterfly Pavilion will open for the spring and summer. In past years, the action has all been inside, in the fluttering realm of some 55 species of moths and butterflies.

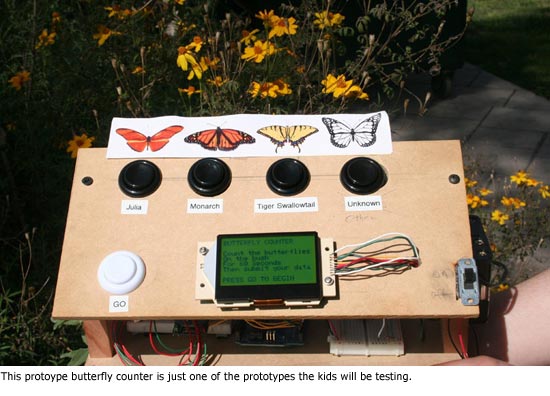

But this April 10 when the Pavilion opens, the creatures with wings won’t be the only ones under observation. In an effort to perfect displays planned for the new North Campus gardens that will open in 2013 at the museum, an assortment of prototype gadgets and interactive science exhibits will be tested throughout the summer in the outdoor space around the greenhouse-like structure.

And museum workers are looking to visitors, young and old, for help.

“We’ll be making observations on how people use these interactive exhibits,” says Lila Higgins, the museum’s manager of citizen science and live animals. “We’ll be talking to visitors, listening to their feedback.”

New displays will be set up, one or two at a time, to see how visitors use them and to pinpoint aspects that need tweaking. Pint-sized focus group (aka kids) are especially invited to weigh in.

Museum officials hope the new garden—part of a sweeping renovation that began last year with the “Age of Mammals” exhibition and that this summer will double the museum’s dinosaur exhibits with a new Dinosaur Hall—will teach visitors more about Southern California’s natural environment and give the museum experience a novel outdoor component. Proposed areas include a Home Garden with vegetables and fruit, an Urban Wilderness featuring many native California flora and fauna and a “Get Dirty Zone” where kids can, for example, play in a dirt pile.

Interactivity, however, is considered to be key, and museum staffers have spent months brainstorming ideas for displays, Higgins says.

“I personally love looking through compost piles and finding little beetles and grubs in there,” she says, “but will other people want to do that?

Ideas that have made it to the prototype stage include a butterfly counter, a periscope that will give children a birds-eye view of the landscape, a gizmo that will let kids sift soil and—dear to Higgins’ heart—a heart machine that will demonstrate how pill bugs break down leaves to help create compost.

“Everybody knows that worms aerate the soil, but not everyone knows what pill bugs do,” says Higgins. “So we were all around the table, with ideas flying around, and we knew we were going to have this Get Dirty Zone, and so we started talking about what pill bugs do. Well, they shred leaves. So what if a kid could have the chance to be like a pill bug? Maybe turn a crank and see that a pill bug’s mouth is like a leaf shredder?”

Within a few months, they had a prototype from Cinnabar California Inc, the Los Angeles firm that designed and built the Age of Mammals exhibit. Devised so that children as young as 5 can access it, it’s a metal mechanism in a wooden box that demonstrates the mechanics of the bug’s mouth.

“I don’t know if I’ve seen anything like it anywhere in the world,” says Higgins. “Maybe it’s a bit wacky, but the first time I saw the mock-up—well, when I see a kid use it, I’m going to be so excited.”

Posted 3/22/11

Fire rescue team airborne again

March 11, 2011

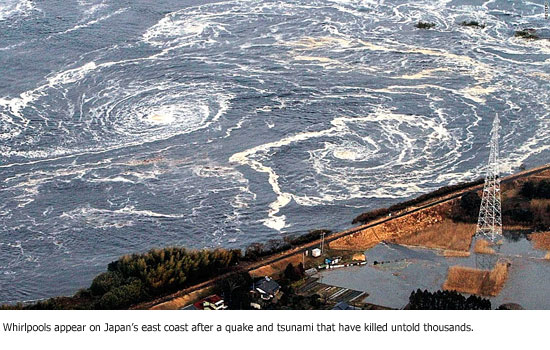

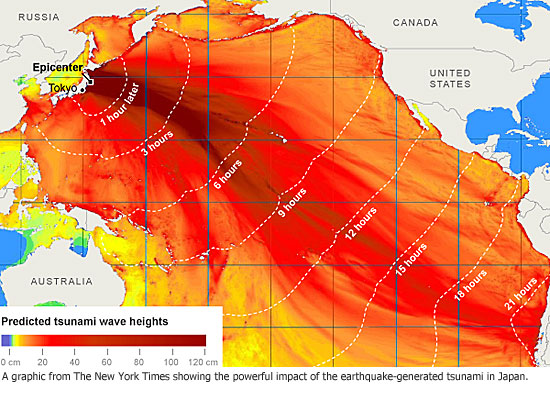

The Los Angeles County Fire Department’s acclaimed rescue team, just days removed from digging through earthquake rubble in New Zealand, is now being dispatched a world away, to the devastated shores of Japan.

The Los Angeles County Fire Department’s acclaimed rescue team, just days removed from digging through earthquake rubble in New Zealand, is now being dispatched a world away, to the devastated shores of Japan.

“You reset, refocus and start planning,” said Battalion Chief Thomas Ewald, who just returned from New Zealand himself and will be helping to coordinate from here the 74-person team’s rescue efforts in Japan, where the death toll from a monstrous earthquake and tsunami is mounting by the minute.

The Fire Department’s California Task Force 2 is only one of two urban search and rescue teams in the country regularly pressed into action by the U.S. aid agency’s Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance. The other is the Fairfax County Fire and Rescue Department. The two had distinguished themselves as the nation’s best.

In a memo to the Board of Supervisors on Friday, newly named Fire Chief Daryl L. Osby wrote: “It is a source of great pride for our organization to not only have this highly specialized response capability but to be called into duty by USAID to help save lives and property beyond our borders.”

The mission at hand differs substantially from those undertaken in the wake of earthquakes in New Zealand and in Haiti, where the team earned international praise for its work in finding and freeing residents trapped for days under buildings. This one will include a swift water rescue component because of the massive tsunami flooding.

Battalion Chief Ewald said that team members, who’ll be transporting with them inflatable rescue boats, have trained for this kind of challenging work at a variety of far-flung locations, including the Colorado River, a Department of Water and Power facility in Sylmar and the Roaring Rapids ride at Six Flags Magic Mountain in Valencia.

“This lets us put people into a controlled swift water environment,” Ewald said of the amusement park training.

The team is scheduled to leave Los Angeles International Airport tonight on a commercial charter flight that will also carry the rescue squad from Virginia.

Posted 3/11/11

A new kind of green incentive

March 10, 2011

Sure, you consider yourself an environmentally conscious consumer doing all you can to reduce your carbon footprint. But spending a few dollars on recyclable grocery bags is one thing, undertaking a costly upgrade of your home to make it more energy efficient is quite another.

Sure, you consider yourself an environmentally conscious consumer doing all you can to reduce your carbon footprint. But spending a few dollars on recyclable grocery bags is one thing, undertaking a costly upgrade of your home to make it more energy efficient is quite another.

Now, however, Los Angeles County can help you put your wallet where your heart is.

The county’s Office of Sustainability is rolling out a program called Energy Upgrade California, designed to reward homeowners with rebates and incentives when they make green improvements to their homes. The program’s goal is to retrofit 18,000 homes while creating 2,000 green-collar jobs and reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 20,000 metric tons.

To drum up interest and participation, a Home Energy Makeover Contest will be held this spring, with winners receiving up to $50,000 worth of energy upgrades to their homes.

Energy Upgrade California—an alliance between L.A. County, cities within the county, Southern California Edison and Southern California Gas Company—is being underwritten by funds from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). The program advocates a “whole house” approach designed to maximize energy savings in both dollars and kilowatts.

Homeowners can take advantage of the program simply by registering online. Energy Upgrade and its partners take it from there.

First, contractors meet with homeowners and conduct a computer modeling of their houses to determine the most efficient and effective level of upgrades. The contractors then make the actual improvements and apply for all government and utility rebates on behalf of the customers. These basic upgrades usually include everything from sealing windows to insulating walls to installing energy efficient water heaters and fixtures.

Additional home upgrades are available upon request, including solar power installations or “green upgrades” that will certify the eco-friendliness and efficiency of your home with a GreenPoint rating.

The initial cost of upgrades can range from $2,000 for a basic package to $8,000-$15,000 for an advanced one. Rebates can total up to $4,500 depending on how much work you have done and how much energy is saved. For the truly committed, spending about $50,000 will bring a house close to zero energy consumption.

Between the rebates and savings from reduced utility bills, it’s possible to partially or completely recoup the initial investment. For $1,000 in improvements (after rebates) it is expected that a homeowner will save 10% in utility costs. The market value of your house will also improve. For more complete examples and explanations see “Meet the Sanchez Family” on Energy Upgrade’s website, or watch their video vignette.

Contractors who want to participate in the program must complete a training workshop, and meet other requirements. To perform services beyond basic house-sealing and insulation, they must be certified by the Building Performance Institute (BNI), a nonprofit organization that works with the Department of Energy and the Environmental Protection Agency to develop home energy efficiency methods.

Meanwhile, to enter the Home Energy Makeover Contest, visit the website by March 31 and be ready with your name, address, phone number, utility provider, information about your home and last years’ utility bills. You must be over 21 to enter and own a home located in Los Angeles County.

Winners will be selected based on their capacity to save energy and serve as examples for future energy-saving homeowners. Five winners will be selected to receive $10,000 each in free improvements. One grand prize winner will receive $50,000 worth of improvements. Complete details on eligibility and prizes are available online.

Energy Upgrade California represents the latest in a nationwide push to protect the environment and create sustainable jobs. There have been some setbacks along the way, but with cooperative efforts like this we may be able to preserve our planet and our pocketbooks at the same time.

Posted 3/10/11

County gets rolling on a new bike plan

March 10, 2011

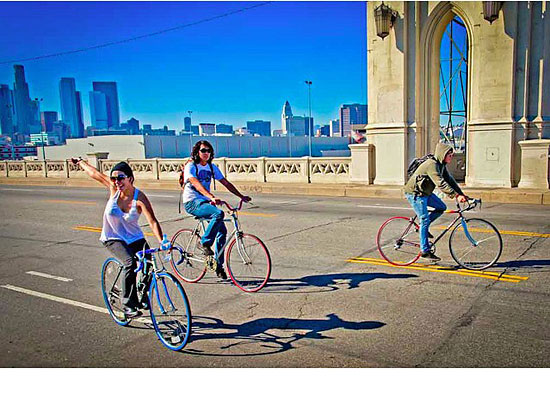

The last time Los Angeles County created a bicycle plan, disco was king, “Jaws” was chewing up the box office and Chevy Chase was channeling Gerald Ford on “Saturday Night Live.”

The last time Los Angeles County created a bicycle plan, disco was king, “Jaws” was chewing up the box office and Chevy Chase was channeling Gerald Ford on “Saturday Night Live.”

Times change, and so has Los Angeles bike culture. Now the county’s jumping into the cycling revolution with both wheels.

A newly drafted Bicycle Master Plan, the county’s first since 1975, puts forth a wide-ranging new blueprint for cycling in Los Angeles County that includes the creation of 695 miles of new bikeways in unincorporated territory over the next two decades, including 20 miles of rider-friendly “bike boulevards.” Nearly 300 miles of the new bikeways would be dedicated bicycle paths and lanes, while the rest would fall under the category of “bicycle route,” in which signage and, potentially, pavement markings, would designate preferred cyclist thoroughfares.

The plan as drafted also contains a range of policy and program recommendations, including support for new “end-of-trip” facilities for cyclists to stow bikes and maybe take a shower; a push for a county “healthy design ordinance”; proposals to make roads safer for cyclists; a recommendation to add bicycles to the county’s transportation fleet; and an endorsement of bicycling as a valid, and growing, transportation option that makes people and communities healthier and more environmentally-friendly.

“It’s a sweeping document in that it provides a vision,” said Abu Yusuf, the county’s bikeway coordinator. “We’re trying to be very proactive.” He said the draft plan is as much about human behavior as it is about infrastructure: “If people aren’t motivated to use the bikeways and to feel safe doing so, they’re not going to use the facilities.”

The plan goes out for a final round of public comments later this month. Once those comments are integrated into the document, the plan, if adopted by the Planning Commission and Board of Supervisors, would become part of the county’s General Plan.

The action on the county bike plan comes as Los Angeles rides a huge wave of cycling activism. The city, to great acclaim, recently approved a new bicycle plan that aims to add 1,680 miles of new bikeways. Bicycle advocates have also pushed for greater law enforcement attention to motorists who hit cyclists, for “sharrows” markings to make it clearer that cars need to share the streets with their two-wheeled brethren, and for bike-friendly amenities like a new “bike corral” in Highland Park and “open street” events like CicLAvia.

“The cyclists have come out of the woodwork, so to speak, in the last 18 months and demanded that government do better. And the county is doing better,” said George Wolfberg, a member of the county’s bicycle advisory committee, which helped prepare the draft plan.

Sam Corbett, a senior associate with Alta Planning + Design, which created the bicycle plan draft for the county’s Department of Public Works, said street-level efforts in Los Angeles are part of a larger national picture.

“I’ve found that grassroots activism plays a critical role in pushing the agenda and elevating the importance of bicycling issues in Los Angeles and in other cities throughout the country,” Corbett said. “Without advocates and concerned citizens’ requests for more bicycle-friendly policies, programs and facilities, there’s no question that we wouldn’t have seen as much progress in the past 10-15 years throughout the country in improving bicycling conditions.”

The county plan proposes adding four kinds of bikeways at a cost of $284.8 million over the next 20 years. Those include some 69 miles of “Class 1” car-free bike paths that would be created in unincorporated pockets across the county, with the largest stretches in the San Gabriel and Santa Clarita valleys. There also would be nearly 225 miles of “Class 2” bicycle lanes, with dedicated space for cycling painted onto roadways throughout unincorporated Los Angeles County.

The county plan proposes adding four kinds of bikeways at a cost of $284.8 million over the next 20 years. Those include some 69 miles of “Class 1” car-free bike paths that would be created in unincorporated pockets across the county, with the largest stretches in the San Gabriel and Santa Clarita valleys. There also would be nearly 225 miles of “Class 2” bicycle lanes, with dedicated space for cycling painted onto roadways throughout unincorporated Los Angeles County.

And the plan calls for creation of more than 380 miles of “Class 3” bicycle routes—primarily in the Antelope and Santa Clarita valleys, but also through the Santa Monica Mountains.

“Don’t get too excited about that, unfortunately,” said Tom Foote, a lawyer who regularly commutes from his Topanga home to his office in Santa Monica. Foote, a member of the bicycle advisory committee that consulted on the report, said no one should expect to wake up one day to find a dedicated bike lane running through the mountains; the topography would make it tough, if not impossible, to widen roads sufficiently.

However, the bicycle route designation would mean bicycle signage and possibly shared lane markings in some areas, and would require future planners to consider bicycle needs when they work on roads in the future.

Finally, the report advocates creating 20 miles of “bicycle boulevards” in the San Gabriel Valley and the county’s central, urban core. Such boulevards—with “calming” features such as traffic circles, along with signage and shared lane markings, added to streets that already have low automobile volumes—have proven popular with families and other riders in places like Berkeley, Corbett said.

The plan covers all of unincorporated Los Angeles county, with nearly 2,657 square miles comprising 65% of the county’s total land but home to just 11% of its population. The sheer size poses difficulties for bicycle planners.

“The challenge in a lot of the county is that it’s vast. There’s a huge amount of space,” Corbett said, noting that while trips of 5 miles or less can be enticing to a would-be cyclist, 15- to 20-mile voyages in places like the Antelope Valley can be daunting.

Another obstacle comes from Los Angeles’ entrenched car culture. “Politically and just practically, it can be challenging to put in bikeway facilities,” Corbett said.

To help overcome those challenges, the plan marshals an array of environmental, health and safety information to make the case for thoroughly integrating bicycles onto Los Angeles streets that have long been considered—by some—to be the exclusive domain of automobiles.

Among its findings:

Streets must be made safer for cyclists. There were 1,307 collisions involving bicycles reported in unincorporated county areas from 2004-2009. Many of those—228—took place in East Los Angeles. On the Westside, there were 56 crashes, with the vast majority (37) occurring in Marina del Rey. “Bar none, safety is the No. 1 concern that citizens have with cycling,” Corbett said. Helping people overcome those fears through education and better design puts more cyclists safely on the streets, the report said.

Bicycling is the green transportation choice. By 2035, increased bicycle use is expected to reduce the number of vehicle trips in unincorporated areas by more than 6 million a year, reducing emissions of hydrocarbons, carbon dioxide and other substances linked to climate change and smog.

Cycling is a public health issue. Bicycle-friendly communities contribute to improved public health by encouraging physical activity and helping to combat chronic diseases such as diabetes and heart disease.

Riding is a lot cheaper than driving. The report said cyclists’ annual operating costs run just 1.5% to 3.5% of motorists’ expenses. (An argument that seems likely to get more persuasive as gas prices move north of $4 a gallon.)

In undertaking its first bike master plan in 36 years, the county has to make up for lost time, and lost funding opportunities. The biggest state source of funding for commuter bike facilities requires master plan updates every five years, Corbett said.

The bike master plan puts the county back in the game—lagging behind places like Portland, New York and even Long Beach, but ready to roll. “It’s undoubtedly a big advance over the last master plan, which is ancient and completely outdated,” Foote said.

“This is a major document,” added Yusuf. “It provides a vision for what the county wants to do.”

Public workshops on the county’s Bicycle Master Plan begin March 28 at 6 p.m. at the Topanga Elementary School. For a list of meeting times and locations, click here.

Public workshops on the county’s Bicycle Master Plan begin March 28 at 6 p.m. at the Topanga Elementary School. For a list of meeting times and locations, click here.

Posted 3/10/11

Young photographers’ vision on display

March 10, 2011

This weekend, the Venice Arts Gallery hosts an opening reception for a new photography exhibit called “Picturing Health,” showcasing more than 50 compelling images captured by young photographers throughout Southern and Central California. Their work reveals more than a bit of tarnish on the Golden State, documenting the community impacts of gang violence, poor nutrition and inadequate health care.

This weekend, the Venice Arts Gallery hosts an opening reception for a new photography exhibit called “Picturing Health,” showcasing more than 50 compelling images captured by young photographers throughout Southern and Central California. Their work reveals more than a bit of tarnish on the Golden State, documenting the community impacts of gang violence, poor nutrition and inadequate health care.

This project was funded by the California Endowment through the Building Healthy Communities initiative, with faith in the power of photojournalism to help expose and correct inequity and injustice in our society.

The reception takes place Saturday from 5 to 8 p.m. at the Venice Arts Gallery, 1702 Lincoln Blvd. in Venice. The exhibit runs from March 12 through April 30. For further information, call (310) 392-0846 or email inquiries to [email protected].

Posted 3/10/11

Beach’s elder statesman looks back

March 10, 2011

Edward Craig remembers waves so oil-polluted that he couldn’t swim without washing himself afterward with turpentine. He remembers beach crowds so environmentally careless that they blithely dumped their trash right onto the sand.

Edward Craig remembers waves so oil-polluted that he couldn’t swim without washing himself afterward with turpentine. He remembers beach crowds so environmentally careless that they blithely dumped their trash right onto the sand.

He remembers when surfers waxed their longboards with the paraffin their mothers used for canning. He remembers when women’s tank suits turned to bikinis and bikinis turned to thongs.

But ask the 70-year-old how many lives he has saved as Los Angeles County’s longest continuously serving lifeguard, and memory fails him. “Oh, my gosh,” he says. “Thousands.” Which makes sense, since Craig has been watching over local beach-goers every summer, without exception, for more than 50 years.

A retired teacher who for 38 years taught music in the Anaheim Union High School District, and who still supervises student teachers at Biola University, Craig has had a second career lifeguarding on weekends and summers since his late teens. County employment records show he was hired in May 1959 and has worked every summer since, including last summer. (One other recurrent lifeguard is older and has an earlier hire date, but records indicate that a medical issue sidelined him last year.)

“I’ve always liked the water,” says Craig, who grew up in Lennox and bicycled as a child down Imperial Boulevard to the ocean. “Riding on the waves as a body surfer, the ocean throwing you toward shore.”

Craig played water polo at Inglewood High School, El Camino College and Cal State Long Beach, and spent his childhood swimming and surfing in the South Bay. His favorite beach as a young man, he says, was the popular Manhattan Beach surf hangout known as El Porto; located near the Chevron oil refinery in El Segundo, its signature attraction is underwater—a deep fissure in the bay floor known as Redondo Canyon, which generates bigger-than-average waves on a consistent basis.

It also generates bigger-than-average crowds and bigger-than-average risks for swimmers—downsides that Craig would learn more about when, at 19, he became an ocean lifeguard. El Porto, which is still where he works most, ended up being his first professional post.

“On my first day on the job, I had 37 rescues,” Craig remembers. “People losing their boards, people stepping into rips. It was a pretty rough day.”

Does he remember the first swimmer he saved? “No,” he says, “but I do remember some amazing rescues over the years.”

There were the two exhausted swimmers he pushed for the length of three football fields on a surfboard to free them from a particularly vicious riptide.

There were the seven kids from Lawndale who ran full-tilt into the ocean, even though they could not swim and Craig had warned them to stay out of the water.

“I had two on the can, one by the hair, one in a cross-chest carry, one holding onto my foot, ” he remembers. “I was out there by myself—all the other guards were involved in other calls that day. Fortunately an older surfer came by and took the other two off my hands.”

Then there was the yellow Labrador who chased a stick into a riptide, leaving his anguished master ankle-deep in water, shouting the dog’s name helplessly at the waves. “The dog was way out there and really struggling—I could just see his nose barely sticking out of the ocean,” Craig remembers.

“I started swimming, wondering how in the world I was going to do this rescue. But when I swam up and I shoved my rescue can under his belly, he put his paws through the front handholds and they got stuck! I was able to drag him to shore, and the guy was so grateful, he came back to the tower with a case of beer the next day.”

Craig was glad, too: “I kept thinking, ‘What if I have to give this dog mouth-to-mouth?’”

Craig says the county’s beaches have changed substantially over the summers. For one thing, they are much cleaner and safer than they used to be.

“There was a lot more pollution. We’d often take a gallon of turpentine along to wash ourselves off after swimming. We’d paint each other down with a big paintbrush—you didn’t want to track that oil through your mom’s house. Also there was a lot of litter—you could look all up and down the beach and not see a trash can. And there was a lot more tar on the beach.”

Now, government regulation and environmental consciousness deter litterbugs and industrial polluters. “The beaches are meticulously cleaned,” Craig says. “We have four trash cans every hundred yards.”

And beach-goers are safer. Lifeguards are more professional, more numerous, better trained and stationed in lifeguard towers that are better equipped and closer together.

“Back in the ’60s, rescues were much longer distance because people would be pulled out farther,” Craig remembers. “Not because ocean conditions were different, but because there were so many fewer of us that by the time we got to them, they could be 50 yards offshore in a big boil. And there were no wave runners to help us out.”

Nor, for many years, was there much law enforcement, at least at El Porto. When Craig started, the beach was an unincorporated “county island” between Manhattan Beach and El Segundo. Packed end-to-end with little surf shacks arrayed along narrow alleys, El Porto was notorious in those early days for the bevies of airline stewardesses who bunked there and the surfers who populated its raucous bar scene. Until Manhattan Beach annexed the 34-acre area in 1980, the nearest authorities were 20 minutes inland at the sheriff’s Lennox substation, he says.

“We had one period in the mid-1970s where a group of armed Nazi surfers declared it their turf,” Craig remembers. “They’d throw things at people from the parking lot and shoot holes into the back of the lifeguard towers.” If someone at the beach was injured, he says, the paramedics of first resort were the lifeguards. Now, of course, El Porto is just another well-patrolled coastal neighborhood in sedate, pricey Manhattan Beach.

One thing that hasn’t changed much is the exceptional fitness required of county ocean lifeguards. Craig still vividly remembers his first lifeguard certification test.

“You swam around a buoy at the Hermosa Pier, and then south to the breakwater, then around another buoy and then back to the beach,” he recalls. “You did this in mid-April, so the water was still quite cold. It was a thousand-yard swim, not counting the 200 yards out and the 200 yards back in, and there were over 200 people, probably, the year I took the test.

“They took the top 25 across the line. I saw the mob going for the buoy and I thought, ‘Oh, my God.’ I was a decent swimmer, but it was daunting. The water was so cold, and the current so strong, and the wind so fierce that almost half the people had to be picked up or brought back in before they covered the first 200 yards.”

But Craig made it: “I was No. 11,” he remembers. “These things stick in your mind. “

Craig still takes the test every year, and still passes. “Obviously I’m not the fastest guy on the beach, but my average time is about 10 minutes, 30 seconds, depending on conditions,” he says.

His fitness regimen is not the average 70-year-old man’s daily workout. A 30-mile bike ride every Monday. An 80-lap swim on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday. Two-miles of wind sprints on the beach, twice weekly. A 3-to-5-mile row in a single-man Dory twice monthly. On-duty workouts daily. Oh, and he still surfs two or three times a month.

“He’s the perfect waterman—an elder statesman of lifeguarding,” says Section Chief Terry Yamamoto of the County Fire Department’s lifeguard division, who has known Craig for three decades, since Yamamoto was a teenager hanging out at El Porto and Craig was the summer lifeguard there. Craig, he says, was one of a handful of lifeguards who mentored him into the profession. Among other things, Yamamoto says, Craig taught him “how to stay calm in all situations.”

“The older you get, the wiser you get in this job,” says Yamamoto. “You can almost predict how people are going to behave on the beach. It becomes instinctual, so that you can be where you need to be almost before something happens.

“We’ve been on literally hundreds of rescues together, and because he’s been on the job for so long, Ed tends to be there as quickly as the younger guys because he knows where he’s going to be needed.”

Nonetheless, Craig says, “this year will probably be my last.”

“I’ve never lost a swimmer,” he says, “and I still feel I could make any rescue I could see. But I’m getting to the point now where you try to be realistic about your career.”

Retiring from the lifeguard tower would give him more time for his music, his wife of 46 years and his two granddaughters; it might also make for some slightly less stressful summers. “Ninety percent of the job is sheer boredom and ten percent is sheer terror,” jokes Craig.

Still, he says, “I don’t think I’ll ever get tired of watching the water—the pelicans flying by, the surf, the sailboats, the ships offloading their supplies. It never changes, and yet it’s always different, always moving. It’s one of the fascinating things about the sea.”

El Porto Lifeguard Station

Posted 2/16/11

Masters of ceremony

March 9, 2011

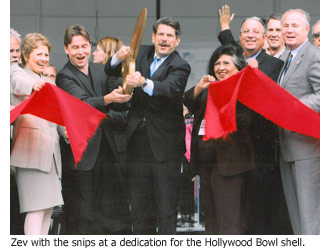

Every time a Los Angeles County dignitary grins into the camera and cuts a big red ribbon, somewhere up there Arthur “Ski” Wisniewski is smiling, too.

Every time a Los Angeles County dignitary grins into the camera and cuts a big red ribbon, somewhere up there Arthur “Ski” Wisniewski is smiling, too.

Back in the early ’80s, Wisniewski, a carpenter and manager in the Internal Services Division, ushered in the county’s modern era of ceremonial snipping when he handcrafted a pair of immense solid wood scissors with sharp metal blades that actually cut.

Of the five original pairs (one for each supervisorial district), only two remain in service. They’re closely guarded implements, ferried to events in custom-crafted cases and quickly packed away once the TV cameras have gone home.

“We have to more or less guard them now,” says Randy Bittner, ISD’s section manager for facilities operations services, who keeps the scissors locked up when they’re not in use. “The guys never take their eyes off them.”

“The guys” are ISD’s special events section—the backstage crew for virtually every public event staged by a county supervisor or department anywhere in L.A. County.

If ceremonial events provide a symbolic narrative of government work in action, these guys are the story’s unsung ghost writers.

They work out of a hangar in East Los Angeles equipped with a carpentry room and well-stocked with folding chairs, tables, lattice backdrops, tents, gold-painted shovels (for groundbreakings) and even a couple of ice machines.

You get the feeling that, given a cake and a deejay, these guys could stage a pretty good wedding reception if they had to. It hasn’t come to that, but they have set up events ranging from hospital wing openings and park gymnasium groundbreakings to postage stamp unveilings and supervisorial trail rides. They created an impromptu “green room” for Seal when he performed at the county’s Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center. Their carpentry work ranges from ADA-accessible walkways to those oak podiums featuring the county seal, regularly seen at press conferences on the nightly news.

“We see our programs on television all the time. I tell my wife, ‘I built that,’ ” says Sylvester “Sly” Anthony, the team’s carpenter supervisor.

As for the scissors, the ISD team oversees a dry run before each event to make sure the ceremonial cut takes place without a hitch. (The advice is always the same: Make sure the ribbon is pulled taut.)

Even though the scissors are as tall as a toddler, they are surprisingly easy to use. Despite being pressed into service at hundreds of events over the years, they’ve held their edge without any special maintenance.

Even though the scissors are as tall as a toddler, they are surprisingly easy to use. Despite being pressed into service at hundreds of events over the years, they’ve held their edge without any special maintenance.

“It’s not like trimming hedges,” Bittner says.

In recent years, they’ve helped to inaugurate projects big and small, including the new County-USC Medical Center, the new emergency room at Olive View-UCLA Medical Center, the Department of Public Social Services’ mobile food stamp sign-up van and a fitness zone at El Cariso Park in Sylmar.

By all accounts, creating the scissors was Wisniewski’s idea.

“I believe he took it upon himself. He just wanted a better, more impressive pair of scissors,” says Paul English, ISD’s division manager of craft operations.

Wisniewski’s decision to equip his creation with a working blade automatically elevated them above the props widely used elsewhere—the ones that look good for the cameras but can’t shear through even the flimsiest ribbon.

“Most of them don’t cut,” English says. “I’ve never seen one with an edge.”

Wisniewski got to see his scissors in plenty of action before he retired in 1997 after 35 years of county service. He died last year, but his scissors remain on active duty—as sharp as ever.

“We like ‘em,” English says. “They’re visually impressive.”

Sowing the seeds of smart gardening

March 9, 2011

For a dozen years, Curtis Thomsen has crisscrossed Los Angeles County, preaching the gospel of gardening.

For a dozen years, Curtis Thomsen has crisscrossed Los Angeles County, preaching the gospel of gardening.

Don’t throw away yard waste, he exhorts. Composting can reduce water consumption by up to 50% per household. And don’t forget the lowly earthworm.

“Worm tea is the strongest organic fertilizer there is,” he likes to say.

Thomsen, an environmental consultant and master gardener based in Cerritos, has conducted the Countywide Smart Gardening initiative for the Los Angeles County Department of Public Works since 1998. Launched 20 years ago as a way to reduce the amount of yard waste being sent to landfills, the program has grown to encompass not only green-waste recycling, but a range of assistance on the creation and maintenance of sustainable landscapes.

The county now operates nine demonstration and learning centers where visitors can learn—for free—about sustainable agriculture, native plants, water conservation and organic gardening. As a bonus, Thomsen’s weekend workshops offer subsidized compost and worm bins for $40 and $65, respectively—a healthy 60% discount.

Countywide Smart Gardening information stands have been installed in parks, schools, community gardens and nature centers. The program’s experts will make presentations at the L.A. County Fair in September and host a booth at the Natural History Museum next month as part of its “Sustainable Sundays” program on “edible landscapes.”

Public Works’ Smart Gardening Program Manager David Perez says the program has educated thousands of Southern Californians, who have been increasingly driven toward home gardening by concerns about the environment and sustainability.

“We do free workshops where the public can learn about composting, where they can see native plants and native gardens, where they can get a feel for the process,” says Perez. And one of the most popular features (besides the discounted composting apparatus) is Thomsen’s no-cost advice.

“I come from an agricultural background—we’ve done composting since I was about 5,” says Thomsen, who was born in San Gabriel and raised on farms in Oregon and Idaho. Thomsen earned bachelors degrees at Oregon State in business administration and statistics, with a special emphasis in agriculture.

He returned to Southern California in the early 1990s to get his certifications in solid and hazardous waste management at UCLA, just as municipalities were working to comply with a then-new law requiring cities and counties to halve the waste they were sending to landfills. Thomsen and his brother, Keith, who holds a Ph.D. from UCLA in environmental science, began working with engineering consultants to help local governments set up composting facilities and recycling programs before the law’s 2000 deadline.

He returned to Southern California in the early 1990s to get his certifications in solid and hazardous waste management at UCLA, just as municipalities were working to comply with a then-new law requiring cities and counties to halve the waste they were sending to landfills. Thomsen and his brother, Keith, who holds a Ph.D. from UCLA in environmental science, began working with engineering consultants to help local governments set up composting facilities and recycling programs before the law’s 2000 deadline.

That expertise, he says, led to the creation of their own environmental consulting firm, BioContractors, Inc., through which Thomsen—with contract oversight from Public Works’ Perez—now runs Countywide Smart Gardening. Thomsen and his crew do 50 workshops a year at the learning centers, plus another 35 or so hosted offsite presentations that are co-sponsored by church groups, nonprofits and other municipalities. Spring is crunch time; between Earth Day observations and demand for spring planting information, his calendar is typically booked solid.

“Right now we’re at 31 events scheduled for April alone,” he says.

“The big push we like to do is vermi-composting because it has so much benefit to the environment,” Thomsen says. That’s composting with worms. Thomsen’s favorites are Eisenia fetida (also known as African Red Worms or Red Wigglers). Bred to thrive in the debris layer of jungle topsoil, they can process massive amounts of organic matter quickly, eating and excreting 80% to 100% of their body weight each day in food waste.

Besides aerating the soil, Thomsen says, they produce manure, or castings, that can be mixed with potting soil to create a high-nitrogen bioactive fertilizer. And, he says, the liquid from those castings—a substance called ‘worm tea’—can be diluted to create a systemic fertilizer, or used straight to kill gnats, aphids, white flies and most weeds.

Thomsen tells his audiences that even regular backyard composting can dramatically improve their garden yield—and make a crucial environmental difference. “The average person in L.A. County generates about a ton of garbage a year,” he says. “Forty percent of that is compostable.”

That’s 800 pounds of table scraps and grass clippings per year per person that could and should be fertilizing yards in L.A. County, “instead of going into a landfill.”

Is composting smelly? “No,” he says. “If you do it right, there should be no odor.”

Is it time-consuming? “No. About three minutes to put the bag of material in the bin and stir. You add water on a weekly basis.”

Does he compost at his house?

Here he laughs. Turns out Thomsen used to, but his current landlords, in Bellflower, are—for now—non-believers in his gospel.

“They won’t let me put in a composter, so I take all my stuff to the office. I have four worm bins there.”

Here is a video introduction to Backyard Composting, brought to you by L.A. County’s Countywide Smart Gardening program.

Posted 3/9/11

Check for the latest closure information

Check for the latest closure information