Disaster Readiness and Relief

The hills have eyes

June 30, 2011

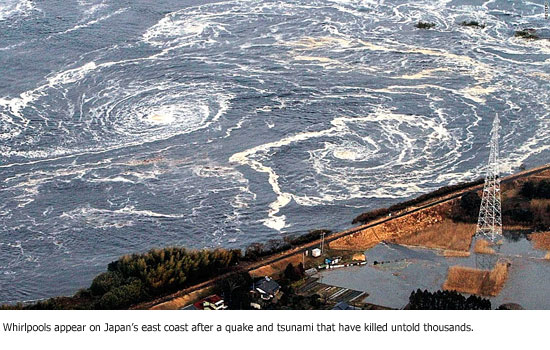

They’ll be watching the fireworks, but not like the rest of us. For them, it’s personal, a call to duty.

On this Fourth of July, the volunteers of Arson Watch once again will be positioning themselves throughout 185 square miles of the Santa Monica Mountains, keeping an eye out for illegal fireworks and holiday revelers who could spark fires in the tinder-dry hills.

“We don’t want a great family holiday to turn into an out-of-control, raging nightmare,” says Sharon Donaldson, public information for the group, which works hand-in-hand with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department.

Like others in the group, Donaldson says that she and her husband joined Arson Watch after a brush with flames themselves. In their case, the “Old Topanga Fire” of 1993 blazed dangerously close to their home while they were vacationing in Hawaii. They watched the whole thing unfold on CNN.

“It was the worst feeling in the world. It was horrifying,” she says. “You’re feeling totally helpless, watching your neighbors’ houses in flames.”

The group was founded in 1982 by the late actor Buddy Ebsen after the “Dayton Canyon Fire” torched his neighbors’ homes and gravely threatened his family and ranch. When he learned that the inferno was arson, he sprung into action. Along with his daughter Cathy, he aggressively recruited his neighbors to help local authorities prevent future fires, forming the original nucleus of Arson Watch.

Today, Arson Watch is staffed by 112 volunteers who log 2,500 to 4,000 hours per year. They assist the Sheriff’s Department at the Lost Hills/Malibu station by patrolling, talking to the public and serving as witnesses. They represent an early warning system in case of an actual fire, notifying fire officials who can try to contain it.

“We are the eyes and the ears of the Santa Monica Mountains when there is fire weather,” says Donaldson, who adds that their presence alone can serve as a deterrent.

While there’s no way to definitely gauge the deterrence effect of Arson Watch, its members note that there has been only one major fire started in the Topanga/Malibu area since the group was launched—the fatal blaze that raced through Donaldson’s neighborhood.

Independence Day, with so many people in party mode, poses some unique and tricky challenges for the volunteers.

For example, on one recent July 4th, an Arson Watch volunteer was alone in remote Tuna Canyon, walking on a fire road where the public is not permitted. There, winds can quickly whip a spark into a wall of flame. The volunteer was soon overwhelmed by a crowd of young people clambering up a bluff to throw an impromptu “rave,” says Donaldson.

She remembers hearing his concerned voice over their two-way radios. Hundreds of partiers were upon him, carrying fireworks and smoking. Refusing his pleas to leave, he enlisted help from the sheriffs, who broke up the dangerous celebration.

According to data from the National Fire Prevention Association, illegal fireworks caused an estimated 18,000 reported fires in 2009, including 1,300 structure fires, 400 vehicle fires and 16,300 “outdoor and other” fires. In all, they caused a reported $38 million in property damage and 30 reported injuries.

The risk is especially high in wildfire-prone regions, such as the Santa Monica and San Gabriel mountains. The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection has already recorded 33 major wildfires in 2011. About two weeks ago, Governor Jerry Brown issued an executive order devoting more resources to fighting and preventing the fires.

This 4th, remember that all fireworks are illegal in L.A. City, unincorporated parts of L.A. County, and in other cities including Pasadena and Long Beach. A few cities such as Gardena and Alhambra permit “safe-and-sane” fireworks–but there are restrictions on who, where, and when they can be used.

The penalties for illegal fireworks can be severe. Small amounts are confiscated and may incur fines, says Sergeant Mark Bock of L.A. County Sheriff’s Malibu/Lost Hills Station. However, aerial fireworks and others like M-80s are considered explosives, and can bring felony charges. If the fireworks injure or kill anyone, perpetrators can be charged with serious felonies like mayhem, manslaughter, or even murder.

Donaldson recommends leaving fireworks to the pros, and suggests contacting law enforcement if you see people lighting them.

“It’s illegal, number one, and it’s not worth it,” she said. “There are amazing fireworks shows everywhere; you can go see these professional shows and not put lives at risk.”

She and her fellow Arson Watchers will be in the mountains this weekend to make sure people heed that advice.

Posted 6/30/11

Time for spring clearing

May 5, 2011

Los Angeles County fire officials once again are on the prowl, inspecting some 40,000 parcels across the region to make sure owners have complied with brush clearance laws.

Los Angeles County fire officials once again are on the prowl, inspecting some 40,000 parcels across the region to make sure owners have complied with brush clearance laws.

“It’s a tremendously huge job,” said Assistant Fire Chief Kevin Johnson, who oversees the department’s forestry program. The goal, he said, is to create “a defensible space” for firefighters to try to stop flames before they reach structures.

The brush clearance ordinance targets areas where there’s a “wildland/urban interface” and requires, among other things, the removal of brush within 50 feet of homes and businesses, Johnson said. Notices were sent to property owners in these areas earlier this year. The compliance deadline for most county residents was last Sunday, with June 1 being the deadline in coastal areas.

Johnston said property owners essentially are given two warnings. After that, the county steps in to clear the brush, charging the costs to the property owners. Last year, 93% of property owners complied, Johnson said, with the county being forced to clear only 32 parcels.

For full details on the Fire Department’s brush clearance program, including a list of private vendors, click here. If you live in the Santa Monica Mountains, check out the “Road Map to Fire Safety,” produced by the Santa Monica Mountains Fire Safe Alliance.

Posted 5/5/11

Wave of tsunami prep heads our way

March 24, 2011

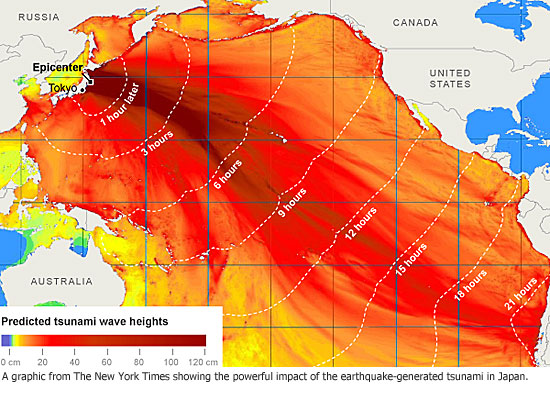

Add this to the list of potential catastrophes that come with living in Southern California: an earthquake-triggered tsunami washing over beaches and harbors and leaving devastation all along the coast.

The nightmarish images of powerful waves buffeting Japan after the March 11 quake there have prompted many to wonder whether the same thing could happen here—and how to escape it if it does. But some Los Angeles experts and planners have been focused on the local tsunami threat long before the first wave hit Japan.

And their assessment of what could be coming our way, and how best to prepare for it, is both simple and complex.

Costas Synolakis, who directs the Tsunami Research Center at USC, said tsunamis triggered by faraway events occur once or more a decade here, and generally pose a relatively minor threat to human safety in Southern California—although they can wreak havoc in the ports by damaging docks and disrupting shipping. A tsunami triggered by a large earthquake in Chile last year did just that, he said—though since it was a Saturday, its impact was less severe than it might have been.

However, a major temblor in the Aleutian earthquake zone in Alaska could pose a significant exception to the general rule about distant-source tsunamis. Such a quake could unleash a powerful tsunami that could endanger both people and property in low-lying coastal communities such as Marina del Rey, Venice and Long Beach, Synolakis said.

To better understand the possible impact of a hypothetical 8.8 quake in the Eastern Aleutian Islands, officials with the U.S. Geological Survey started work in January on their first-ever emergency planning “tsunami scenario” for Southern California. Modeled on the Great California ShakeOut, the scenario, when completed in 2013, will assess how such a tsunami would affect the region economically, environmentally and as an emergency response challenge. It also could serve as the basis for future tsunami response exercises.

Whether they end up causing minor or major damage, tsunamis that originate far away come equipped with one important safety feature: forecasters can see them coming, often hours in advance, allowing time to alert the public and evacuate beach areas likely to be affected.

A “local-source” tsunami would not be so kind. A tsunami triggered by a nearby offshore earthquake could trigger an underwater landslide, causing profound and fast-moving damage all along the Santa Monica Bay—with little or no time for evacuations.

“The landslide event keeps me up more at night because it’s far less predictable,” Synolakis said.

On the upside: it’s an exceptionally rare occurrence, taking place once every 2,000 to 3,000 years, he said.

The Board of Supervisors voted to designate this week “Tsunami Awareness and Preparedness Week” in Los Angeles County, part of a national effort that includes videos like this one.

Planning for any kind of tsunami in Los Angeles County is complicated because there’s no way of knowing in advance which kind will strike.

However, here are some guidelines to improve your odds of staying safe and dry.

Know where you are:

Tsunami “inundation zones” are located all along the coast. Check out this map for a more detailed look at the terrain in various communities. In Marina del Rey, recently-posted signs designate entry and exit points for the tsunami zone, and also point out evacuation routes. “We were fortunate to get one grant to do one [sign] demonstration. We wanted to show it could be done. We just finished it in March,” said Jeff Terry, program manager for the L.A. County Office of Emergency Management.

Make friends with your local emergency services coordinator

With fourteen incorporated cities along the coast, evacuation routes and response plans can vary. In unincorporated Marina del Rey, the latest evacuation map is here.

When the earth moves, get away from the water:

“For most of L.A. County, it’s simply a matter of moving away from the beach,” said Keith Harrison, assistant administrator of the county’s Office of Emergency Management. Resist the temptation to stick around and watch the action; these aren’t ordinary waves.

Don’t expect a siren:

The best source of emergency information will be on radio, TV or online. Los Angeles County emergency response officials said it would be impractical and too expensive to install and maintain enough sirens along the coast to serve as an effective warning system. In addition, the county’s “reverse 911” system, known as Alert L.A., allows authorities to rapidly telephone every land line in the county with emergency information. To be even better plugged in, you can…

Register your cell phone number and e-mail address with Alert L.A.:

Land lines already are covered but take a few minutes to sign up to make sure that official emergency information reaches you wherever you are.

Sometimes the best way out is on foot:

In the event of a fast-approaching local-source tsunami, people in the tsunami zone may have only 5 to 20 minutes to get to higher ground. “Most places you walk up a couple blocks and you’re safe,” Terry said. Added Harrison: “On foot is what we recommend. Don’t get in a car.” For people in a high-rise building, the best response to an extremely fast-moving tsunami could be to climb to a higher floor. (But If there’s time to evacuate, leaving the building and setting out for higher ground would be the safer course.)

The county’s overall tsunami plan was approved in 2006. It’s a good start, but there is still more to do, Harrison said. “One of our goals is to eventually qualify for the “tsunami-ready” designation by NOAA,” he said, referring to the program administered by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Individual county departments have their own plans, and already are working to incorporate insights gained from the recent events in Japan.

“When you look at the video of Japan, it’s apocalyptic. It’s almost surreal, like a movie shoot. It does definitely hit home,” said Santos H. Kreimann, director of the county’s Beaches and Harbors department. “It’s consciousness-raising.”

His department used its new Twitter account to send out messages about the tsunami advisory issued for the Los Angeles coast following the quake in Japan. And it’s been busy ever since with logistical questions such as how best to communicate with and evacuate “live-aboards” who reside on boats in the marina, and figuring out how to relocate the department’s earth-moving equipment far enough from the coast so it will be safe and available for cleanup work after the crisis is over.

“The Japanese event required us to really look at this closer and try to get things done sooner rather than later,” Kreimann said.

Posted 3/2211

County rescuers back in town—for now

March 24, 2011

You could call them the masters of disaster.

But even with an internationally-acclaimed skill set and more frequent flier miles than you can shake a boarding pass at, Los Angeles County’s urban search and rescue team has never before had a run—or a wake-up call—quite like this one.

No sooner had they returned from their post-earthquake work in Christchurch, New Zealand than they were summoned to Japan less than 36 hours later to help with the aftermath of the deadly quake and tsunami there.

No sooner had they returned from their post-earthquake work in Christchurch, New Zealand than they were summoned to Japan less than 36 hours later to help with the aftermath of the deadly quake and tsunami there.

“That is a first for us as a team,” said Battalion Chief Tom Ewald, who between disaster assignments heads up the county Fire Department’s Battalion 3, serving East Los Angeles and nearby communities.

The back-to-back deployments made for some joking around on the tarmac as the team—formally known as California Task Force 2—came back from mission No. 2.

“Let’s make it more than 36 hours this time before seeing each other again,” they told each other before heading home at last.

But the lessons learned on both missions are no laughing matter. And they hit close to home for members of the team because both New Zealand and Japan are affluent, highly-developed countries with many similarities to Southern California.

But the lessons learned on both missions are no laughing matter. And they hit close to home for members of the team because both New Zealand and Japan are affluent, highly-developed countries with many similarities to Southern California.

“We write off a lot of the lessons learned in underdeveloped countries,” such as Haiti, Ewald said, because of stark differences in building codes and other factors.

This time, “some of the takeaway was how these types of disasters would have impacted Los Angeles County.”

“Christchurch looks just like downtown Pasadena, or Long Beach,” he said. And as for the tsunami that devastated Japan: “Their only crime there was having exposure to a coastline, which we also have…How would we respond if that kind of widespread, catastrophic event had happened here?

“The skills we learned there are directly transferable.”

“The skills we learned there are directly transferable.”

Ewald said both incidents point up the need to further hone disaster planning and preparedness in Los Angeles, and suggest that a “decentralized decision-making” process may be required in the event of a massive catastrophe like that experienced in Japan.

On a personal level, Ewald—who managed to grab the time to watch “American Idol” with his family between deployments—took advantage of some rare down time early in the week to drop out of sight, as far as work was concerned.

“I kind of kept myself below the radar,” he said. “My cup runneth over.”

California Task Force 2 returned home from Japan on Saturday, March 19. This YouTube video captures the homecoming, as does this CBS Channel 2 video. An array of still images showing the team’s work in Japan and New Zealand is on Facebook. And a National Public Radio report is here.

Posted 3/23/11

Fire rescue team airborne again

March 11, 2011

The Los Angeles County Fire Department’s acclaimed rescue team, just days removed from digging through earthquake rubble in New Zealand, is now being dispatched a world away, to the devastated shores of Japan.

The Los Angeles County Fire Department’s acclaimed rescue team, just days removed from digging through earthquake rubble in New Zealand, is now being dispatched a world away, to the devastated shores of Japan.

“You reset, refocus and start planning,” said Battalion Chief Thomas Ewald, who just returned from New Zealand himself and will be helping to coordinate from here the 74-person team’s rescue efforts in Japan, where the death toll from a monstrous earthquake and tsunami is mounting by the minute.

The Fire Department’s California Task Force 2 is only one of two urban search and rescue teams in the country regularly pressed into action by the U.S. aid agency’s Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance. The other is the Fairfax County Fire and Rescue Department. The two had distinguished themselves as the nation’s best.

In a memo to the Board of Supervisors on Friday, newly named Fire Chief Daryl L. Osby wrote: “It is a source of great pride for our organization to not only have this highly specialized response capability but to be called into duty by USAID to help save lives and property beyond our borders.”

The mission at hand differs substantially from those undertaken in the wake of earthquakes in New Zealand and in Haiti, where the team earned international praise for its work in finding and freeing residents trapped for days under buildings. This one will include a swift water rescue component because of the massive tsunami flooding.

Battalion Chief Ewald said that team members, who’ll be transporting with them inflatable rescue boats, have trained for this kind of challenging work at a variety of far-flung locations, including the Colorado River, a Department of Water and Power facility in Sylmar and the Roaring Rapids ride at Six Flags Magic Mountain in Valencia.

“This lets us put people into a controlled swift water environment,” Ewald said of the amusement park training.

The team is scheduled to leave Los Angeles International Airport tonight on a commercial charter flight that will also carry the rescue squad from Virginia.

Posted 3/11/11

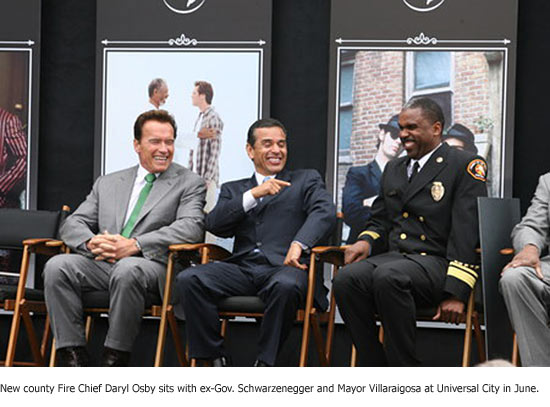

First black picked as county fire chief

February 23, 2011

In a historic choice, the Board of Supervisors on Tuesday announced that it has selected Daryl Osby as the next chief of the Los Angeles County Fire Department, making him the first African American to hold that position in an agency that had been slow to integrate.

In a historic choice, the Board of Supervisors on Tuesday announced that it has selected Daryl Osby as the next chief of the Los Angeles County Fire Department, making him the first African American to hold that position in an agency that had been slow to integrate.

Osby, a 27-year veteran of the department—and the son of a career firefighter who led fire departments in Inglewood, San Jose, San Diego and Oceanside—will assume the top job next month after the retirement of long-serving chief P. Michael Freeman.

Most recently, Osby, 49, has been in charge of the department’s business operations. He also has worked as the top commander of fire operations for a number of major incidents in recent years, including the massive fire siege in 2003, the 2005 Topanga Fire and the 2008 Wildland Fires. He also spent 18 days in Louisiana in the wake of Hurricane Katrina helping to manage recovery efforts there.

“I’m shocked but excited,” Osby said when reached in a meeting moments after the announcement of his appointment. “It’s emotional. It’s awesome to think that the board has the confidence in me to replace Chief Freeman, who has led this department for more than two decades.”

He said he was profoundly aware of the milestone his appointment represented.

“I think it’s important to understand the sacrifices not just of African Americans, but of all people who pave the way,” Osby said. “I’m excited to be the first African American, but above and beyond that, I think the board chose me because they felt I was the best candidate for the position. First and foremost, I’ve just tried to be the best individual and the best member of the fire service that I could be.”

Osby was chosen from a short list of finalists comprised entirely of department veterans. Freeman—who worked for 24 years in the Dallas Fire Department before coming to Los Angeles—has said in interviews that one of his biggest challenges was the “steep learning curve” he faced as an outsider. He suggested that the county might do well to hire its next chief from within to oversee the department, which has a budget of some $923 million and a service area roughly the size of Delaware.

Osby’s elevation is significant for a department in which diversity issues—including the recruitment and treatment of women—has been a concern.

Although the city of Los Angeles’ fire department has had black firefighters since the late 1800s, the county didn’t hire its first African American firefighter until 1953, and didn’t promote a black until the mid-1970s, after a discrimination lawsuit began to progress toward the U.S. Supreme Court. The hiring rendered the case moot by the time the high court heard it.

Today, diversity advocates within the department note that while the department has hired more than 1,000 firefighters during the past decade, only about 50 of them have been African American.

His appointment also represents a kind of continuity, however.

Born in the San Diego County community of National City, Osby is the son of a veteran fire chief. His father, Robert, was in the fire service for more than four decades before retiring as Oceanside’s first black fire chief in 2005.

The younger Osby joined the Los Angeles County Fire Department at the age of 23 in 1984 as a firefighter and paramedic. He rose steadily through the ranks, gaining experience in virtually every aspect of the department’s firefighting and internal operations.

By 2000, he was an assistant fire chief in charge of community services, public information and executive planning. The following year, he was promoted again to oversee emergency service, personnel, training and budget issues for 76 fire stations in more than 30 unincorporated areas. In 2008, he became chief deputy, initially oveseeing the county’s emergency operations and later taking responsibility for the department’s business operations, including employee relations and financial management.

That experience is expected to be crucial as the department—like the rest of county government—grapples with massive cuts in the state budget and a proposed “realignment” of responsibility and funding.

“Budget-wise, our priority is going to be that we have a sound financial plan and not have our spending exceed our revenues,” said Osby. “We’ve worked hard here to find efficiencies and work smarter, and we’ll continue that.” Among the department’s challenges, he added, would be the need to update the its infrastructure and address a number of pressing construction issues “while trying to maintain efficiencies and not have it impact public service.”

And, said Osby, the father of two daughters, diversity would continue to be a priority, in gender as well as ethnicity. Only about 1 percent of the department’s firefighters are women, for example, and Osby said one of his first jobs will be to “sit down with all our stakeholders and come up with a strategic approach.”

“We need to look at strategies to ensure we have proper outreach to let people know that this is a career for everyone,” he said. “Some people still don’t see that. And we need to break down those barriers.”

Posted 2/8/11

Our rescuers Down Under

February 22, 2011

Los Angeles County’s disaster rescue-and-recovery team was mobilizing today to head to New Zealand, where a 6.3 magnitude earthquake crushed buildings and killed at least 65 people—a toll that is expected to rise as the search for the dead and injured continues around Christchurch.

The 74-member unit, known as “California Task Force 2,” was expected to leave at 2 a.m. Wednesday.

The team, made up of Los Angeles County firefighters, paramedics, emergency room doctors and other specialists, earned high marks for its work after the earthquake in Haiti. The urban search and rescue squad also has seen action in previous emergencies including Hurricane Katrina and the Oklahoma City bombing.

They’re traveling to New Zealand at the request of the U.S. Agency for

International Development and U.S. Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance, County Fire Chief Daryl Osby said in a letter to the Board of Supervisors.

“It is a source of great pride for our organization to not only have this highly specialized response capability, but to be called into duty by USAID to help save lives and property beyond our borders,” Osby said.

A fire department official is also heading to Washington, D.C., to help coordinate the team’s efforts in New Zealand.

The task force will be commanded by Battalion Chief Tom Ewald, a 19-year county fire department veteran who heads up county fire’s Battalion 3, serving East L.A., Bell and nearby communities. He worked as the team’s Pacoima-based deployment coordinator during the Haiti operation, and took part in disaster response operations after 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina.

When his day started Tuesday, Ewald had been preparing for another kind of trip. “I thought I was going home to get ready to take my family skiing,” Ewald said. “That all changed around 7 a.m.”

By early afternoon, the final arrangements were underway to transport staff and equipment to New Zealand. Ewald said the team will be ready to work as soon as they land.

“Once our equipment is off the aircraft, we can be operational within an hour,” Ewald said. “They have work sites already identified for us.”

It’s a high pressure assignment in a dangerous setting far from home. But for the Los Angeles County team, Ewald said, it’s nothing they haven’t seen before.

“It’s what we do as professional rescuers, day in and day out. We’re just plying our skills in somebody else’s backyard.”

Posted 2/22/11

Assessing the tragedy

January 18, 2011

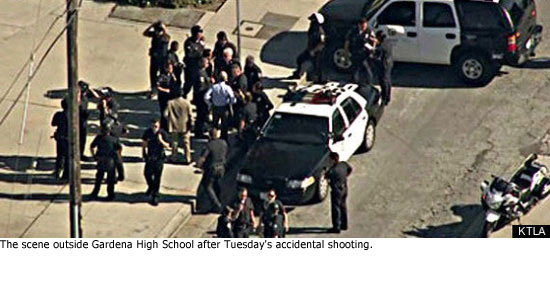

The 911 calls flew from the terrified crowds to the police dispatchers and, within minutes, to the desk of Tony Beliz: Shots fired at Gardena High School. Students wounded.

As tragedy swept through yet another campus on Tuesday morning, Beliz—deputy director of the Department of Mental Health’s emergency outreach bureau and part of an elite cadre of county mental health and law enforcement experts—rolled out to confront the questions that in the past three years have become a specialty for the School Threat Assessment Response Team.

What causes school shootings? Can they be prevented? And what is the best, and safest way to handle the aftermath?

Launched in the aftermath of the Virginia Tech massacre that left 32 dead in 2007, the county’s so-called “START” program helps schools cope with—and — and head off– such catastrophes. The first comprehensive program of its kind in the nation, START brings schools, mental health professionals and law enforcement together to prevent and deal with campus violence.

In situations like Gardena’s—in which a gun in the backpack of a reportedly frightened teenager apparently accidently fired, wounding two students with a single bullet—Beliz says he and his colleagues will make themselves available for after-the-fact mental health counseling and other support to the students and school, should it be needed. In other situations, the teams intervene early to evaluate the public threat of students exhibiting mental health problems.

START’s mission—and that of threat assessment teams like it on campuses all over the country—has been especially relevant in the wake of high profile incidents both nationally and locally.

In Arizona, a threat assessment team at Pima Community College identified Jared Lee Loughner as a potential concern months before the gunman killed six people and injured 13 in Tucson, but the larger community response was too fragmented to stop him.

Closer to home, at Cal State Northridge, school mental health counselors and campus police worked together last week to hospitalize and arrest a 22-year-old student who had not only allegedly threatened students and staff, but also had hidden firearms and explosives in his dorm room.

CSUN Police Chief Anne Glavin established the department’s threat assessment program after her arrival in 2002. Still, the department turned to county mental health officials for help at one point in ensuring that all the doctors involved understood the gravity of the student’s behavior. The student, who has pleaded not guilty, is being held on $1 million bail.

On Tuesday, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted to develop a plan to expand programs like START as a way to better identify students with mental health problems that might threaten public safety.

“Timely intervention has likely prevented a number of school tragedies,” said Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, who introduced the motion asking the Department of Mental Health and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department to explore ways to expand school violence prevention services.

“The continued presence of conditions that contribute to the frequency and severity of school-based threats make the need for an ongoing and expanded comprehensive prevention and intervention program readily apparent,” Yaroslavsky said.

Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas agreed, citing the Gardena incident.

“This kind of shocking occurrence proves that we must do everything in our power to eradicate the roots and causes of violence on our campuses,” he said.

Since its inception, START has responded to some 250 incidents of potential violence at elementary, middle school, high school and college campuses. START teams average about 200 student referrals a month, Beliz says.

The staff, comprising about 120 county clinicians and 80 law enforcement officers in Los Angeles city and county, Long Beach, Santa Monica and Pasadena, has worked closely with a variety of school districts and local universities, although the bulk of its work has been with the Los Angeles Unified School District and Los Angeles County Office of Education.

Not every school takes advantage of the program, but when they do, START makes a difference.

“There was a college student last year who had decided to stop taking his meds and was contemplating hurting himself and other people,” Beliz remembers. “And recently a 7 year old boy came to our attention, a really disturbed little boy who is fascinated by killing animals. We just saw a 13-year-old who had somehow tasted the blood of dead animals and was fascinated with violence.”

Protecting the safety of students can sometimes be tricky, requiring an understanding of possible motivations behind the potential violence, Beliz says.

“Often the schools want to expel the kid who’s made the threats,” Beliz says. “Well, think. Because with some kids, that’s the final justification. So we remind schools that every action triggers a reaction, and help them develop appropriate plans beyond zero tolerance.”

And, he says, START helps all the disparate agencies and helping hands of Greater Los Angeles find and interact with each other—no small feat in this massive metropolis.

“We try and make sure all the dots are connected,” Beliz says.

Posted 1/18/11

At the intersection of safety and tragedy

December 2, 2010

On Feb. 12, 2008, a commercial fire broke out near Compton. A Los Angeles County fire truck rushed east along 135th Street toward the scene. Lights flashing, siren blaring, the truck was doing 35 mph when the light turned red at Figueroa Street. Firefighters thought everyone had stopped or pulled over. So, downshifting, the truck rolled through the intersection en route to the emergency.

They were mistaken. A catering truck had suddenly made a left turn into the fire truck’s path. In the back of the vehicle, court documents would later show, an $80-a-day cook named Antonia Roman had just finished warming tortillas for the next stop. Unrestrained by a seat belt, she was making her way back toward her passenger seat when the crash sent the catering truck careening onto its side.

Roman, a 43-year-old mother with a 6-year-old son still at home in Montebello, was thrown from the wreckage. When she regained consciousness, she was a paraplegic. The firefighter behind the wheel, meanwhile, would later discover that, in the course of a few years, the county’s policy for negotiating intersections on emergency calls had changed without his knowledge, requiring him to come to a full stop at the light, rather than to slow to a speed that was safe for the situation.

This week, the Board of Supervisors approved a $3.3 million settlement to Roman in the case.

The incident is significant, and not only because the injuries were so tragic and the settlement so substantial. It also highlights, once again, a complex, life-and-death question that public safety workers and policymakers deal with every day: What is the safest, best way for the driver of an emergency vehicle to negotiate an intersection when lives are in the balance?

In 2008, the last year for which statistics are available, there were 340 collisions involving emergency vehicles on Code 3 calls in California, 116 of them at intersections, according to the California Highway Patrol. The collision that crippled Roman was one of 36 involving emergency vehicles in Los Angeles County intersections that year.

Although the law is clear for civilian drivers—when an emergency vehicle approaches, you stop or pull over and yield the right-of-way—answers are not as definitive for those on the other side of the lights and sirens.

The California Vehicle Code exempts emergency vehicles en route to 911 calls—fire trucks, ambulances, police cars, etc.—from many rules of the road, including those involving red lights. The sole stipulation is that that the vehicle be driven at a speed that’s safe for the road conditions and “with due regard for the safety of all persons using the highway.”

Within those parameters, however, policies vary among agencies and jurisdictions when it comes to balancing the urgency of the call against the need for safety.

“The law says you have to clear the intersection—you can’t just blow through it,” says California Highway Patrol Executive Lt. Kevin Gordon. “You have to make sure it’s safe to proceed and that other motorists are aware of your presence. But there are variances in how best to implement that.”

The policy of the Los Angeles City Fire Department, for instance, is to “stop at all red lights and stop signs . . . and when safe, proceed through the intersection with caution.” The Pasadena Fire Department’s policy does not spell out whether a full stop is required when entering an intersection against a red light. However, the department’s emergency response procedures list “driving against traffic lights” as one of a series of conditions that require “reduced speed and extra caution.”

The county’s policy, meanwhile, has gone back and forth in its attempt to maximize safety, from a 2000 policy that instructed drivers to “slow to a speed which would allow observation of approaching vehicles and pedestrians” to the policy in force at the time of the collision, which told drivers to “stop at all signal controlled intersections that display a red light . . .”

Since then, the policy has again been updated, requiring that the driver simply apply the law with caution and “clear the intersection, lane by lane, until all traffic has yielded the right of way.”

An overview presented to the Board of Supervisors in connection with the Roman case suggests that those shifts may have been confusing. Listed among the factors that “gave rise to [the] accident” was a “failure to be aware of and adhere to the current Department driving policy” on the driver’s part, and a similar failure by his captain to make him aware of the policy.

“We’re trying to learn from what happened,” says Los Angeles County Fire Chief P. Michael Freeman. The challenge, he says, is in balancing the need for swift, potentially life-saving emergency response with the need to navigate traffic safely as public safety workers rush to deliver help.

Traffic safety is crucial, he says, but bringing a heavy truck to a full stop and then getting it up to full speed again takes time when every moment counts. What’s more, he says, stopping at an intersection may confuse other drivers about whether they should stop, go or look for flames around them.

Says the chief: “It’s a question of what’s safest for the public and what’s safest for the people on the other end of the 911 call we’re trying to get to.”

Posted 12/2/10

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink