Justice and the Courts

Realignment gets all too real

October 6, 2011

Inside a cramped, dingy-white building in Alhambra, one of California’s most radical—and some say reckless—experiments in its criminal justice history is unfolding. There, officials are getting a detailed first look at some of the thousands of state inmates who’ll be supervised by Los Angeles County once they’re freed, a process that began this week.

Inside a cramped, dingy-white building in Alhambra, one of California’s most radical—and some say reckless—experiments in its criminal justice history is unfolding. There, officials are getting a detailed first look at some of the thousands of state inmates who’ll be supervised by Los Angeles County once they’re freed, a process that began this week.

So far, it’s not an encouraging sight.

Hundreds upon hundreds of prisoner files—some woefully incomplete—are haphazardly arriving by mail, fax and Fed-Ex at Los Angeles County’s “pre-screening” hub in the Probation Department’s Alhambra field office. Eagle-eyed probation workers are uncovering mistakes, large and small, in the state records, including inmates who should be sent to other counties and others whose crimes should disqualify them entirely from the new “realignment” program.

Only late last week, after intense pressure from L.A. County, did state corrections authorities even begin sending comprehensive mental health records on ex-convicts headed here for supervision, information that’s crucial in developing treatment plans for the clients and protection for the public.

What’s also become increasingly clear in recent days is that the state has not been entirely forthcoming about the fine print of the controversial realignment plan, which is aimed at reducing prison overcrowding while slashing the state’s budget deficit.

Again and again, the governor and legislature have publicly stressed that the ex-inmates who’ll be supervised by the counties are “low-level” offenders convicted of non-serious, non-violent, non-sexual crimes. They also note that these individuals would have returned to their home counties no matter who was responsible for their oversight. But that’s not the whole story, as L.A. County officials are quickly learning.

These same felons could—and sometimes do—have prior cases involving very serious crimes. Under the realignment law, AB 109, only the most recent conviction, or “commitment offense,” is considered in determining whether inmates will be supervised by counties or state parole agents after their release.

Take, for example, one inmate who was scheduled to be freed on Wednesday and has been ordered to report to L.A.County for post-release supervision. He was serving time for second-degree commercial burglary, attempted grand theft of personal property, forgery and identity theft—all non-serious, non-violent crimes under the penal code. But over the previous decade, he had more than a dozen arrests or convictions for a slew of serious and violent crimes, including assault with a deadly weapon, robbery and terrorist threats.

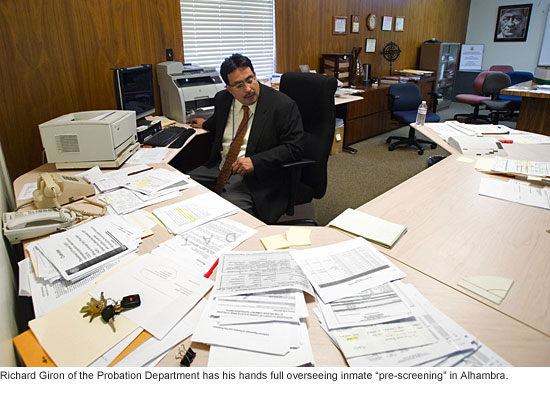

“We’re literally seeing every criminal record you could think of,” says Richard Giron of the Probation Department, who’s in charge of the pre-screening center in Alhambra, where nearly 2,000 files have been received. “We’re seeing prior violence, prior sex offenses—the full range of minimal criminal records to extensive, serious records.”

Giron says his staff is flagging such individuals for heightened supervision as part of the case plans developed when inmates arrive at other hubs throughout the region for face-to-face interviews.

Reaver Bingham, the Probation Department’s deputy chief of adult services and juvenile placement, called some of the county’s new charges “very hard core” but insisted that his agency is trained and prepared to deal with them. “This population is not unfamiliar to us,” he said, noting that the department currently supervises 15,000 adults with histories of serious and violent crimes.

In recent weeks, as AB 109’s October 1 implementation date drew near, concerns about public safety took center stage, with the harshest warnings coming from Los Angeles County District Attorney Steve Cooley. He predicted that crime rates would soar not only because of the freed inmates who’ll be under county supervision but because, under the law, defendants convicted of non-violent, non-serious crimes will now be sentenced to county jail rather than state prison. He and others argue that this will lead to even greater jail overcrowding and more inmates being released early by the Sheriff’s Department, which manages the sprawling system.

In the Alhambra screening center, Giron and his hand-picked team understand the high stakes for public safety and are determined to make sure no inmate is erroneously placed under the county’s jurisdiction. His 11 deputy probation officers and two supervisors scour every document the state sends and then comb criminal databases, as well as court records, for additional information on each of the inmates scheduled for release.

In the process, Giron says, his staff has uncovered mistakes that have given county officials ammunition to keep dozens of inmates from falling under probation’s purview.

“I’m doing everything I can in my power to reject cases that are inappropriate for supervision in L.A. County,” Giron says. Those cases have included an inmate who’d been serving time for molesting a child under the age of 14, a prisoner convicted of a serious extortion attempt and yet another who was described by the state’s own prison board as not safe to be released.

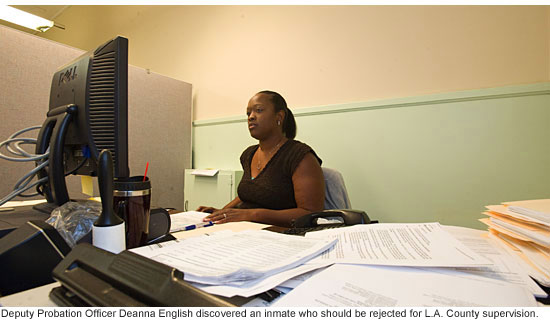

On Wednesday morning, Deputy Probation Officer Deanna English, a 22-year veteran of the department, found yet another, using the scant information contained in the state’s own file as a springboard.

Corrections officials had determined that a 20-year-old inmate at the California Rehabilitation Center in Norco was eligible for county supervision because, according to a release form, he was serving time for a second degree burglary. But that was wrong. Contained within the file itself was the notation that he’d been sentenced for a robbery, a serious crime that would exempt him from the realignment program. English says she then checked the actual court record, which confirmed the robbery conviction.

“Honestly speaking, I thought they were trying to pull one over on us,” she says of corrections officials. “Their thing is to get as many [inmates] out of the state system as they can.” English says she feels “a high sense of duty” to thoroughly vet every file.

Making the job even more challenging for the Alhambra crew is the fact that the state has no centralized point of contact. The county is receiving files from 33 separate prisons. And those files are not being sent based on the chronological release dates of inmates, dates that seem to be constantly shifting.

Just the other day, as Giron talked with a visitor from Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s office, another probation supervisor, Al Montellano, walked up with a handful of documents fresh off the fax. They stated that eight inmates scheduled for release on December 4 will now be freed on October 23, meaning that the time-consuming review of their cases will have to be rushed into the mix, putting others on hold.

“That,” Giron says with a hint of understatement, “is operationally inefficient.”

Progress finally has been achieved, however, in one of the most crucial facets of the screening process—determining the mental health status and needs for the estimated 20 percent of inmates coming to the county who’ll need some level of treatment.

For months, the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health, a key player in the realignment process, had been stymied in its efforts to obtain comprehensive treatment records for inmates. The information provided by the state was simply a notation that mental health services had been delivered in prison.

“We were getting promises and assertions that were not true,” says Dr. Marvin Southard, director of mental health. “It was very frustrating.”

Among other things, Southard says his department was directed to dial an information number on the inmate forms. “If you call that number, you get a correctional counselor—the cell-block staff person—but they have no access to the medical records,” Southard says.

Further, according to Southard, his staff was told that they’d have to individually contact each of the state’s 33 prisons for information, which would consume crucial time in learning an inmate’s needs and creating a treatment plan.

The issue reached a boiling point two weeks ago when the Board of Supervisors voted to send a stern letter to Gov. Jerry Brown. In it, they warned that, unless the necessary information was forthcoming, “we will not accept parolees with mental health issues.”

“After that, everything changed,” Southard says, noting that a centralized system was developed by California’s corrections officials. “The governor’s staff promised that we’d get the records we need.”

Still, even if the county manages to overcome all these logistical challenges, there’s still the overarching question of whether the state will provide the money necessary to make it all work today and in the future.

“This has been my concern from Day One,” says Supervisor Yaroslavsky. “We’ve been asked to take a leap of faith that the reimbursement is adequate to meet our responsibilities. You can’t blame us for being skeptical, especially given the problems that have emerged in the opening days of this program. Even though the governor has assured us he will make us whole, it’s not entirely up to him and that makes me nervous.”

Posted 10/6/11

Supes OK “win-win” jail phone pact

September 20, 2011

The Sheriff’s Department will, indeed, get a new jail phone vendor, promising cheaper calls for families of inmates and a bigger share of phone revenues for the county’s Inmate Welfare Fund.

The Sheriff’s Department will, indeed, get a new jail phone vendor, promising cheaper calls for families of inmates and a bigger share of phone revenues for the county’s Inmate Welfare Fund.

Under the new contract with Public Communications Services Inc., the county’s share of revenue for the Inmate Welfare Fund will rise to 67.5%, with a guaranteed annual minimum of $15 million. That’s a 30% increase over the $10 million or so that was generated for the fund last year.

Meanwhile, the price of a collect call from jail will be cut from $3.54 to $1.25 for the first minute, with a 15-cent-per-minute charge thereafter. The price of a 17-minute phone call will fall 30% to about $3.65.

“This is a win-win,” said Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, who congratulated Sheriff Lee Baca for changing direction three years ago after the Board unanimously denied the department’s request to extend the contract with the current vendor, Global Tel*Link, and insisted that it be put out to competitive bid.

“It wasn’t your original path forward, but once it became the Board’s path forward, you did it with zeal, and I think the results are spectacular.”

PCS was the top scoring bidder among four who were vying for the contract, including the current vendor, GTL. Shortly after PCS submitted its winning bid, the company, then headquartered in Los Angeles, was acquired by GTL, which in the past year or so has acquired at least one other rival and has announced plans to acquire at least two more.

The terms of PCS’ bid are binding regardless of the change of ownership, according to the contract approved by supervisors on Tuesday.

The new contract, which takes effect in November, will cut the price of calls to public defenders via a special speed-dial number to a flat 12 cents per minute. Families of international callers will be charged a 50-cent connection fee in addition to the cost of the call, which will vary according to the country.

Calls to Mexico, for instance, will cost 50 cents to connect plus 50 cents per minute thereafter and calls to El Salvador and Guatemala will cost 50 cents plus 95 cents per minute; calls to most other countries will cost $1.25 per minute after the connection fee.

Sheriff’s officials told the board that the contract will cover some 5,800 phones in the jail and probation system—one of the largest public phone systems in the state.

Posted 9/20/11

New jail phone plan may be a win-win

September 8, 2011

Families of Los Angeles County inmates who’ve been forced to pay unusually high rates for collect calls from jail telephones could soon find relief under a proposed new contract that also would generate more county revenue.

Families of Los Angeles County inmates who’ve been forced to pay unusually high rates for collect calls from jail telephones could soon find relief under a proposed new contract that also would generate more county revenue.

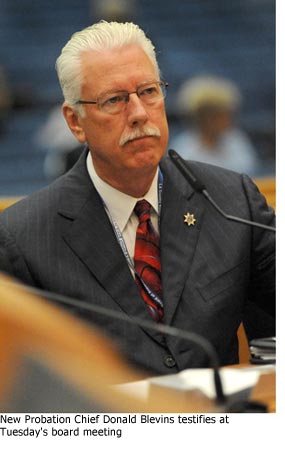

A proposed change of vendors, outlined in a letter to the Board of Supervisors from Sheriff Lee Baca and Chief Probation Officer Donald Blevins, would cut rates for an average phone call from the county lockup by about 30% while adding millions in guaranteed annual funding for key inmate programs and jail maintenance.

Tentatively scheduled for consideration by the board on September 20, the recommendation to hire Public Communications Services, Inc., is the result of a competitive bidding process urged by critics, including Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, who complained that families were paying too much for jail phone calls and that the county was receiving too little in the existing contract’s revenue sharing provisions.

“My argument from Day One has been that if the rates were less burdensome on inmates families who were being overcharged, then more calls would be made and more money would be generated for the Sheriff’s Department,” Yaroslavsky said. “Now we have a proposal in place that hopefully will achieve those objectives.”

The price of phone calls from county jails has been controversial. Studies show that maintaining close contact with families via phone, correspondence and visits, can reduce recidivism among inmates and improve their chances of a successful reentry into society.

High phone rates deter that crucial communication. But they can also indirectly benefit inmates because, by law, the county’s portion of revenues from jail phones must go into special Inmate Welfare Funds that underwrite educational, recreational and other projects that are geared to them.

Debate over the rates charged to Los Angeles County jail phone users dates back several years to early preparations for the renewal of the current contract, which is held by Global Tel*Link Corp., a private, Alabama-based company that provides jail and prison phone systems nationally.

GTL had offered a $3.5 million fee to the county in exchange for a contract extension. The sheriff, meanwhile, argued against opening the contract to competitive bidding, saying that it might damage the department’s revenue stream.

But the supervisors and County CEO William T Fujioka insisted that putting the contract out to bid would be the best way to lower prices and maintain funding.

“I’m absolutely convinced, you put this out on the street, we’re going to get a more competitive contract,” Fujioka told Supervisors in 2008. Ultimately, in the fall of 2009, a competitive process was undertaken, leading to the new proposal.

The push for more competitive rates comes amid a shrinking competitive landscape. In fact, the winning bidder, PCS, was acquired by GTL three months after the bidding closed. GTL is among the larger firms in the prison telecommunications sector; PCS, whose customers include the Michigan Department of Corrections, was its Los Angeles-based rival.

Earlier in 2010, GTL acquired another competitor, Digital Solutions Inc., and has announced plans to acquire at least two more this year, Conversant Technologies Inc. and Value-Added Communications.

Unlike phone contracts that govern the rates of residential users, jail phone pacts have had little regulation, allowing a handful of specialized service providers to charge whatever the market will bear.

Such high prices allow carriers to offer counties lucrative revenue sharing arrangements on contracts that, in Los Angeles County’s case, have typically amounted to millions of dollars a year.

But the situation has had its downsides. Families of inmates—many of whom are among the poorest people in the county—have borne some of the highest phone rates in California at a time when the price of phone service in even far-flung places has been slashed by technology.

Under the county’s current contract, GTL charges families of Los Angeles County jail inmates $3.54 for the first minute of a collect call—more than almost every other county jail in Southern California and about seven times the price of a 50-cent pay phone call. The Sheriff’s Department gets 52% of the revenue generated by the roughly 5,400 phones in the county’s jail system—a split that last year generated about $10 million for the county’s Inmate Welfare Fund.

In contrast, the 5-year PCS plan would cut the first-minute rate to $1.25, with a 15-cent-per-minute charge thereafter. The cost for an average 17-minute inmate phone call would fall from about $5.20 to around $3.65. The new contract also would increase the county’s share of revenue to 67.5 percent, with a guaranteed minimum of $15 million annually for the Inmate Welfare Fund and $59,000 for the county’s Probation Department.

Lt. Ronald E. Gilbert of the Sheriff’s Inmate Services Bureau said PCS was one of four bidders whose names will become a matter of public record after the supervisors’ upcoming vote.

Gilbert said PCS submitted its proposal before bidding was closed in August, 2010, three months before its acquisition by GTL. The terms of PCS’ bid would be binding, despite the change in ownership, Gilbert said, adding: “They’re still their own entity. As far as the contract is concerned, we’re dealing with them as PCS.”

Gilbert said the proposal’s guaranteed revenue is especially welcome in a time of constricted state funding. In recent years, Gilbert said, the county’s share of money has dropped as steep budget cuts have prompted the release of thousands of inmates from overcrowded jails while the tough economy has forced families to limit phone time with those who remain incarcerated. Gilbert predicted that the lower prices would likely increase inmate calls, which during the first six months of this year numbered 2.4 million.

“It generates a more stable income stream for the Inmate Welfare Fund, and it benefits the inmate and family population,” he said. “Everybody seems to win on this deal.”

Posted 9/8/11

State prisoners, meet your minders

July 27, 2011

After a rare public tussle between two powerful local criminal justice agencies, the Board of Supervisors has unanimously picked the Los Angeles County Probation Department to oversee thousands of freed California prisoners who, as part of the governor’s budget plan, will no longer be charges of the state.

After a rare public tussle between two powerful local criminal justice agencies, the Board of Supervisors has unanimously picked the Los Angeles County Probation Department to oversee thousands of freed California prisoners who, as part of the governor’s budget plan, will no longer be charges of the state.

Chief Probation Officer Donald Blevins was given the nod over Sheriff Lee Baca, who had forcefully argued that his department was better suited to monitor an estimated 8,000 inmates who’ll be heading back to the streets of Los Angeles County during a nine-month period.

Critics of Baca’s proposal argued that such sweeping new duties would create public confusion over the mission of a department charged largely with suppressing crimes, not rehabilitating those who commit them. In Los Angeles and throughout the state, that job traditionally has been the responsibility of probation and parole agencies.

The board’s decision on Tuesday was based on a motion by Supervisors Michael D. Antonovich and Don Knabe, who noted that the Probation Department “has been providing supervision and rehabilitative services to adult probationers for over a century.” For that reason, they said, the agency has the kind of infrastructure and expertise that makes it best qualified to run the so-called “post-release community supervision program.” But the supervisors also called for a role for the Sheriff’s Department in identifying and, when necessary, apprehending high-risk parolees in the program.

The truth is that county officials at all levels wish they’d never had to confront the issue in the first place. Earlier this year, they argued strongly against being forced to take responsibility for the freed inmates, a key facet of Gov. Jerry Brown’s “realignment” budget strategy to save money and reduce prison overcrowding. Faced with the county’s fears about funding and strains on a local jail system already tearing at the seams, the state agreed to pay for the first year but has yet to fulfill its promises for funding beyond that.

The ex-inmates, whose releases are scheduled to begin October 1, are known as “non, non, nons”—meaning non-violent, non-serious, non-sex offenders. Under a new state law, those who violate the terms of their release will no longer be returned to state prisons. With few exceptions, they’ll serve a maximum of 180 days in county jails.

That same law also mandates that counties create an operational plan—including staffing, budget needs and re-entry services—through new multi-agency Community Corrections Partnerships. In L.A. County, the CCP will submit a plan to the Board of Supervisors for approval in August, one that is likely to include a role for the Sheriff’s Department.

Indeed, during Tuesday’s meeting Baca made clear that his department would not be relegated to the margins. “When it comes to managing high-risk parolees,” he said, “I’m not going to ask the chief probation officer for permission. I’m just going to do it.”

Obviously irritated, Baca also criticized Blevins for statements in a report to the chief executive officer in which he “literally had kind of drawn a moat around his department and looks upon me and my department as some kind of threat to the traditions of rehabilitation when, in fact, we are at the forefront of rehabilitation for parolees.”

During the meeting, Blevins, who chairs the county’ CCP, did not address Baca’s comments. But he later told the Daily News that the Sheriff’s Department would have a role in the oversight of the soon-to-arrive ex-inmates, albeit a limited one.

“Our original plan,” Blevins was quoted as saying, “was for absconders or individuals who have been working with probation but need a higher level or more intensive supervision, we would ask [the sheriff’s] assistance on those kinds of cases…The sheriff has indicated they are 24/7 and they can provide those kinds of services.”

Posted 7/27/11

Touring Hall of Justice, by flashlight

November 3, 2010

The temperature outside was pushing 90, but when the padlock came off the chained doors of the Hall of Justice, the air rushed out like a chilly blast from the crypt.

Inside, though, the legendary 1925 building looks like it’s starting to wake up from its big sleep.

The Hall of Justice—where Charles Manson, Bugsy Siegel, Sirhan Sirhan and a host of other big- and small-time criminals once cooled their heels, where Marilyn Monroe’s body ended up after her suicide and where Robert Mitchum once did time for marijuana possession—is one of downtown’s Los Angeles’ most striking landmarks.

Red-tagged and vacant since the 1994 Northridge earthquake, the Hall not so long ago was rat-infested, debris-ridden and home to the occasional transient.

Now its interior has been cleaned out and virtually gutted.

Later this month, the county Board of Supervisors will be asked to approve the selection of a firm to undertake the historic rehabilitation and retrofitting that will turn the site into the new headquarters for the Sheriff’s Department. Staff from the District Attorney, Public Defender and Alternate Public Defender also will be stationed in the building, located at Spring and Temple, across from the criminal courts building.

Work on the three-year project is expected to begin early next year. The approximately $244 million Hall of Justice rehabilitation, along with other capital projects, will be funded in part by “Build America” bonds whose issuance was approved by supervisors on Wednesday. The project’s cost is expected to be partly offset by lease savings for the departments that will be relocating to the building.

Alicia Ramos, who has been overseeing the Hall of Justice project for the county Department of Public Works since 2004, said that years of advance work have been devoted to “trying to create the cleanest slate we can” for the new office space interior.

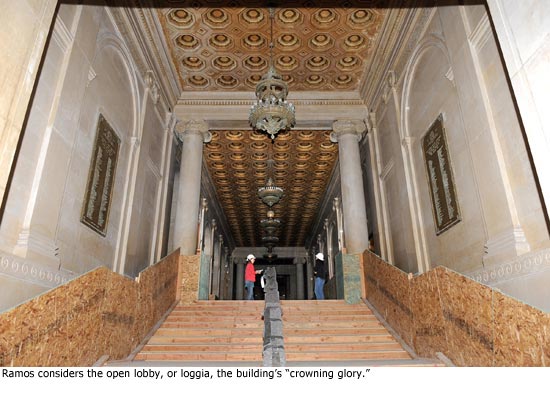

On Tuesday, Ramos led a writer for Supervisor Yaroslavsky’s website and a county photographer on a flashlight-illuminated tour that started in the building’s basement and ended on its rooftop. A gallery of photos from the tour, below, offers an unusual glimpse inside the building as it awaits its transformation.

To get to this point, tons of debris—including about a half million dollars’ worth of recycled jail cell bars—have been hauled away and reams of once-confidential documents have been incinerated and sent to that great repository in the sky. (See update below.) Elevator shafts now stand empty, their vintage wood-and-brass cabs sidelined until they can be pressed back into service with a modern operating system.

All of the building’s jail cells have been ripped out. One cell block, said to have housed Manson, has been preserved and relocated to the first floor, where it eventually will be opened to the public as part of a new museum/interactive center focused on the history of the building and the sheriff’s department.

The building’s courtrooms, once the site of trials that included the Sleepy Lagoon murder case, have all been demolished except for one, which is being preserved right down to its embellished plaster corbels and will be restored and used as a sheriff’s conference room. The same goes for a wood-paneled law library nearby. Both are located on the building’s 8th floor, where the sheriff will have his office.

The plan to bring the Hall of Justice back to life includes seismic reinforcement; new electrical, plumbing and mechanical systems; a 1st floor cafeteria that will be open to the public; and a nine-level, 1,000-vehicle parking structure, half of it underground.

The building’s open lobby, or loggia—which Ramos calls “the crowning glory of the Hall of Justice’—also is awaiting restoration. Even in its current state, the loggia exudes glamour and gravitas, from its marble columns to its elaborate ceiling and chandeliers. Covered up for the moment are its terrazzo floors and historic iron-and-brass stairs.

“It’s dramatic. It’s the scale, it’s the materials,” said Ramos, 37, an architect and Cal Poly Pomona grad. “It really can take you back to a period.”

Even in its current state, the Hall—whose architectural style is variously described as Beaux Arts, Italian Renaissance or Federalist—holds no terrors for Ramos, despite its sometimes macabre past.

“I haven’t gotten any ghost stories out of this building,” she said. Those she’s heard from others can be logically explained. (Voices in the basement, for instance, are more likely coming via a closed-up tunnel from an adjoining county building, not from the spirit world beyond.)

“They’re all stories to me. I’ve never seen anything wicked or sinister,” Ramos said.

She even ventured inside the Hall alone occasionally, like the time she came inside to photograph a judicial seal inside the law library.

Later, she was there when a transient who’d been caught living in the building was escorted away by police.

The man looked at Ramos. “He said, ‘I know you. I’ve seen you walking through here.’ The hair went up on my neck.”

Nowadays, she said, “I don’t go through the building by myself.”

Up on the building’s roof—once a prison yard-style exercise area for inmates that may be turned into a jogging track for employees—Ramos reflected on everyone and everything these walls have seen.

“Between Marilyn Monroe and Charlie Manson,” she said, “it’s kind of the good and the bad that come through these kinds of facilities.”

Photos by Scott Harms/Los Angeles County

Posted 11/3/10

Updated 11/4: Regarding questions about the destruction of documents, sheriff’s officials said Thursday that they removed all records from the Hall of Justice and left behind only trash or outdated forms. Department of Public Works officials said they exercised an abundance of caution and treated all papers left behind as confidential because they were not in a position to evaluate them. They said all documents were destroyed in accordance with the county’s policy.

Naomi and the homeboys

October 28, 2010

His homies call him “Cranky,” and he’s the first to admit he doesn’t have much of a sense of humor. Nothing funny, he says, about his first 16 years of life, not with what he’s seen and done.

So when the do-gooder Israeli lady showed up at Camp Gonzales in the Santa Monica Mountains to talk to the incarcerated teenagers about how to have healthy relationships with women—specifically, girlfriends and wives—“I thought it was real corny, like it wasn’t for me.”

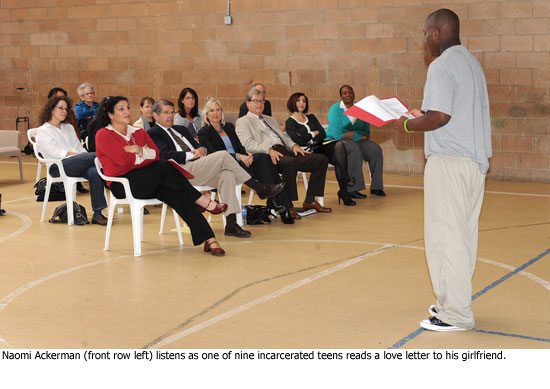

Yet here he is, standing before a small audience in the probation camp’s gymnasium this week, reading a love letter he’s written to his girl on the outside.

“I hope by the time you receive my letter, the sky is cleared up beautiful, and full of life, just like that special someone you are.”

One by one, eight more wards of the system quietly step forward, young men whose crimes—many of them violent—seems wildly out of whack with their boyish missives:

“No one can compare to the beauty I see in your eyes.”

“I need you in my life, I’m sorry for the damage that I caused you.”

“I love you and wanna be with you, but if you feel another man can treat you better than I can, let me know.

And so it goes, each letter followed by applause, each teenager exploring a tender side that few of them have seen in their own families, a side they believe can get them hurt in neighborhoods ruled by gang machismo. For now, though, they feel safe; none have mailed their letters—yet. As one author jokes, if his note hit his sweetheart’s mailbox, she’d say, “That’s not my boyfriend writing.”

And besides, mailing the letters isn’t really the point of Relationships 101, a pilot program created by American-born Israeli Naomi Ackerman and brought for the first time to one of the county’s Probation Department camps, where minors are sentenced for commitments of up to 9 months. It was funded with $3,500 from Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s office.

Ackerman says that the letters—combined with role playing, word association and improvisation—are a starting point for participants in probation camps or in high schools to understand the power of words to create sick or healthy relationships.

“Change has to start somewhere,” Ackerman says after the program’s culmination on Monday. “If you start by writing, then maybe you can say the words aloud and then, finally, begin to act more gently and compassionately…In the many squares of sorrow and horror in their lives, if one square can have peace and sanity and goodness, then I’m happy.”

***

In a sense, Ackerman’s relationship with the young men is proof of her premise. Although she’s had only about a half-dozen sessions with them since summer, you can see they like and respect her. An actress and playwright, she communicates directly and openly. Most important, when they speak, she listens. Ackerman knows that the challenges she faces here are far greater than those she’s confronted at private academies or public schools such as Fairfax High.

How many of you, she asks, have seen a relationship that’s lasted more than five years? Out of 10 participants, only two answer yes. Their grandparents, they say.

“When I listen to their reality on the street,” she says. “I don’t know how I can change that. I’m telling them to speak nicely to their girlfriends and then they go into their neighborhood and someone is going to shoot them in the face.”

Still, she got her captive audience to dial down their attitudes during four one-hour workshops, the first of which began with an excerpt from her powerful one-woman play, “Flowers Aren’t Enough.” It’s the story of a bright woman from an upper-middle class family whose husband gradually and brutally isolates her, before she finally reclaims her life. Ackerman has performed her play more than 1,000 times throughout the world.

But the real buy-in for the group, Ackerman says, came when she played the Annie Lennox song, Thin Line Between Love and Hate, in which a woman has been treated so badly for so long that she finally takes violent revenge on her man.

This, they get—a real-world consequence to the mistreatment that Ackerman’s been talking about. It touched a nerve for them all. “It made us calm down,’ says one participant, making them realize that, despite varying crimes and allegiances, “we had something in common.”

***

It’s nearly showtime at Camp Gonzales, a place that houses 90 minors between the ages of 16 and 18. Children’s advocates have praised the facility for its forward-thinking programs and emphasis on counseling and staff interaction. Which is not to say the place is soft.

Just days before the performance, Ackerman says, three of her participants are yanked and placed in lock-up for fighting. “Don’t take this away from them, too,” Ackerman says she begged, successfully.

Before the guests start arriving (they’ll include Yaroslavsky and the Probation Department’s new No. 2 man, Cal Remington), Ackerman lays down some of her own expectations for the nine fidgeting and distracted participants as they sit in a row of plastic chairs.

“I know it’s not in your nature, but it will not kill you if you smile,” she says, sounding like the Israeli military sergeant she once was. “You look like you’re going to a funeral. What these people think about you is that you only know how to be tough.”

She also gives it to them straight that their behavior could impact her hopes of getting more funding to expand Relationships 101 to other Probation Camps.

“Today is about money,” she says. “I’m not going to lie to you. But it’s also about you, what you’ve done.” So act accordingly, she warns. No grabbing your crotches or other kinds of street-posturing behaviors.

With the audience now seated and hushed, Ackerman tosses a rubber ball to one of the boys, who laterals to another. Each barks out a word that Ackerman says has no business in a relationship. Hate. Unfaithfulness. Unreliable. Dishonest. Cheating. Violence…Then the flipside. Trust, Respect. Commitment. Affection. Faith. Love…

With the audience now seated and hushed, Ackerman tosses a rubber ball to one of the boys, who laterals to another. Each barks out a word that Ackerman says has no business in a relationship. Hate. Unfaithfulness. Unreliable. Dishonest. Cheating. Violence…Then the flipside. Trust, Respect. Commitment. Affection. Faith. Love…

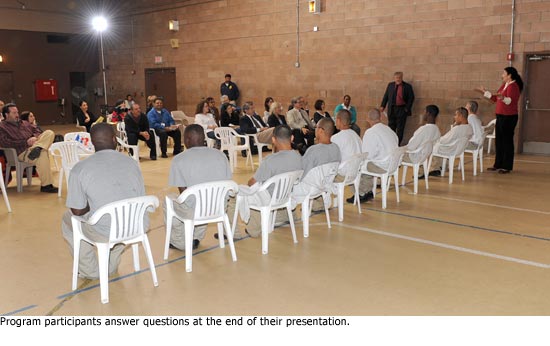

During the next half-hour or so, the teenagers perform role-playing exercises on how to handle situations (some don wigs to act as girlfriends) and, of course, they read their love letters. But the most revealing part comes during the unscripted session at the end, when the young men take questions from audience members whose lives would likely intersect with theirs only in a venue like this.

Surprisingly, they’re anxious to answer, seemingly energized by the reality that their visitors sincerely want to hear their opinions and experiences. Smiles suddenly come easily to them all.

Cal Remington asks how they’ll carry into the outside world the lessons they’ve learned in the program.

“Homies are kind of slow, you know,” one of them explains to the department’s second-in-command. “I’ll have to break it down for them, get it through their thick heads.”

Laughs all around.

A woman then asks what the young men would do if their sisters or mothers were being abused. One voice emerges above the others anxious to answer. He says he’d give him “some advice” to stop. “But I’m not gonna lie. If it’s my blood, I’m not going to let it go. I’d give him some of his own.”

Reality-check all around.

***

With the audience gone, Ackerman gathers her guys in a circle. “Incredible, incredible, incredible,” she says.

The boys don’t want her to leave. “I’m not saying good-bye,” she assures them. She says she’ll return to share with them a video she’s made of the event. Maybe, she says, they can perform at another camp, maybe one for girls. More smiles.

“I just want to say thank you, Naomi,” says one 16-year-old, confessing that “it was hard to do this in front of so many people.”

“A round of applause for Naomi,” says another of the teens.

And with that, their clapping fills the empty gym.

Posted 10/28/10

Homeboy gets an intervention

September 14, 2010

The famed Homeboy Industries—dedicated to giving gang members an alternative to street life—has been given a helping hand to navigate its own future.

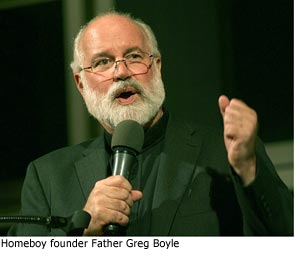

The Board of Supervisors on Tuesday approved a $1.3 million contract with the financially ailing Homeboy Industries to provide job training, counseling and tattoo removal for gang members seeking new lives. Earlier this year, faced with a $5 million shortfall, Homeboy was forced to layoff hundreds of staffers.

“This will be an enormous help,” said Father Greg Boyle, the Jesuit priest who founded Homeboy Industries, the nation’s largest gang-intervention program. “It helps us keep the doors open and continue to offer hope.”

In May, Boyle was forced to slash staffing from 427 to about 100 because of a crippling money crunch brought on by the recession, an expanding clientele and the organization’s costly expansion in 2007 to a new Chinatown headquarters.

Despite the cutbacks, Boyle kept open Homeboy’s bakery, café and other businesses. But he was forced to call on volunteers to perform services crucial to the program’s broader mission, such as counseling, mental health assistance and tattoo removal.

Founded in 1992 in Boyle Heights, Homeboy Industries’ slogan is: “Nothing stops a bullet like a job.” The organization says it helps 12,000 gang members yearly with educational, mental health, legal and job-training services. It runs five businesses, including Homeboy Bakery, Homegirl Café, as well as a silk-screen and embroidery shop and a janitorial and maintenance company.

Boyle said the county contract is recognition of the important role Homeboy plays in guiding Los Angeles gang members along the road from incarceration to independence.

“It’s really heartening and gratifying that the county has confidence in us,” said Boyle, whose recently published memoir is called “Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion.”

“The county,” he said, “has never asked us to be the after-care and re-entry program for gang members, but that’s what we’ve been.”

Since Homeboy’s highly publicized layoffs, the organization says it has raised $4.3 million in donations from foundations and individuals. As a result, staff levels rose to about 200 during the summer and included Homeboy’s executive team. Boyle said Homeboy has a $9.5 million budget, with revenues from its businesses totaling $3.5 million.

Still, Mona Hobson, Homeboy Industries’ director of development, said the organization isn’t out of danger. She said Homeboy must raise $13.3 million by the end of 2011 to cover expenses and establish a $2 million reserve fund for the first time. Hobson said that means Homeboy needs to raise roughly $7.5 million more.

The new L.A. County contract, which runs through June 2011, will fund, among other things, tattoo removal, job counseling and development and mental health services for 665 probationers and other high-risk individuals between the ages of 14 and 30. In addition, it will pay 20 trainees to work at Homeboy businesses.

Supervisors approved the contract 3-0. Supervisors Mark Ridley-Thomas and Michael D. Antonovich were absent for the vote.

Boyle said Homeboy negotiators sparred with the county over a few key points. The county initially wanted the funding used exclusively for clients referred to Homeboy by the Probation Department. But Boyle made the argument that a client who voluntarily seeks the organization’s services may be more motivated than someone who is compelled to participate.

Boyle said Homeboy negotiators sparred with the county over a few key points. The county initially wanted the funding used exclusively for clients referred to Homeboy by the Probation Department. But Boyle made the argument that a client who voluntarily seeks the organization’s services may be more motivated than someone who is compelled to participate.

The two sides agreed that the funding would support a mix of referrals and walk-ins.

Homeboy officials also opposed a request that services be pre-approved by county officials—a fee-for-service arrangement that Boyle argued could cause harmful delays and deter clients.

“If a client comes in and says he wants mental health counseling, we want to provide it right away,” Boyle said. “He may not come back later. Why would you put up obstacles?”

Homeboy has had state, city and county contracts in the past, mostly for pilot programs that are separate from the core services that will be supported by its new pact with the county.

The “reentry grant” contract, as it’s called, will provide funding to cover portions of salaries for 17 existing staffers, including case managers, job developers, mentors and three mental health therapists.

Under the contract, Veronica Vargas, Homeboy’s chief operating officer, will become the project director. Homeboy’s current director of case management, Mario Prietto, will serve as program manager.

The contract also provides $100,000 to fund two UCLA scholars from the School of Public Affairs to evaluate the program’s outcomes. The researchers have been studying Homeboy for two years under a private grant. They’ll keep track of clients’ attendance, retention and re-incarceration rates, comparing them to other county programs aimed at similar populations.

Vargas said that Homeboy welcomes the scrutiny.

“We want to prove that we are a national model,” she said. “We’re very cost effective. A dollar goes a long way at Homeboy.”

Click here for a short documentary on Homeboy Industries.

Posted 9-14-10

Report says Probation rife with problems

August 25, 2010

In a searing critique, a top official of Los Angeles County’s Probation Department says the agency has been plagued by weak management, poor communication, entrenched perceptions of favoritism and staffers who would never have survived a rigorous background check.

In a searing critique, a top official of Los Angeles County’s Probation Department says the agency has been plagued by weak management, poor communication, entrenched perceptions of favoritism and staffers who would never have survived a rigorous background check.

“It appears that problems were ignored continuously and defective operations were allowed to ‘muddle by’ with little emphasis placed on getting back to the basics to become a high functioning organization,” Remington wrote.

Five months in the making, the report by the department’s current chief deputy, Cal Remington, provides a study in organizational dysfunction across multiple fronts, particularly in the Administrative Services Bureau, which he says affects every phase of the department. The bureau includes such responsibilities as internal affairs, budget and fiscal services and human resources.

Remington’s 67-page report—called “Back to the Basics: The Steps Required While Moving Forward”—was presented to the Board of Supervisors on Tuesday. It offers 131 recommendations to improve management, increase transparency and accountability, and improve services and staff morale while cutting improprieties and poor performance.

The supervisors mandated the report in March as the 6,100-person department, the nation’s largest, was being rocked by disclosures that, among other things, employees used county credit cards to buy electronics goods, that dozens of employees accused of misconduct escaped discipline because the investigations ran too long and that the department could not fully track $79 million allocated by the Board largely to hire personnel.

In an interview, Remington said the department already has jettisoned ineffective staffers from important middle and upper management positions “and replaced them with people who are competent.”

Remington’s proposed fixes range from sweeping strategic changes, such as developing new programs as alternatives to incarceration, to relatively quick fixes that include launching a department newsletter to boost morale. He said the department should also continue to build on a June report by the watchdog Office of Independent Review, which called for an overhaul of internal discipline.

In his report, Remington said he was surprised by the broad community interest among children’s advocates, parents, service providers and others in improving the department’s operations, only to be rebuffed by the organization. “One individual,” Remington said, “indicated that community groups have been knocking on Probation’s door for years, however, the Department would not let them in.”

That situation, he stressed, must be changed.

“The future focus of this Department clearly needs to be on community-based alternatives to incarceration; more programs focusing on families and programs that prepare juveniles and young adults to become productive citizens of the community,” Remington concluded. “This can best be accomplished by working with community-based organizations.”

Remington, a retired probation chief from Ventura County, was acting head of the department in March when he launched his study, serving until new Chief Probation Officer Donald Blevins arrived in April. He now serves as the department’s chief deputy.

He said there must be more transparency in promotions to end nepotism and cronyism that has led to a widespread “feeling that ‘it isn’t what you know, but who you know’” when it comes to promotions. Remington said managers complained to him that “unqualified candidates are promoted with systemic favoritism, nepotism, and chicanery.”

That same attitude among staffers—a sense of being on the outside—extended to the way information has sometimes been conveyed in the department, Remington said, particularly when it comes to personnel issues. This, he said, has created a workplace where “rumors are prevalent and run rampant.”

He also had some harsh words for “a few” members of the department’s executive team. These individuals were described in interviews as “being rude and having abusive ways in dealing with subordinates.” These top-tier individuals also were described as “being involved with infighting and cliques that have been destructive.”

The report urges that all managers receive mandatory ethics training and calls for the creation of a succession plan that includes a “leadership academy” to groom staffers for promotion.

To improve future hiring, Remington said standards must be raised for background checks. He said that based on his review of disciplinary cases, some employees should have been “screened out at the background phase.” Unlike most departments that hire peace officers, he said, probation does not use a polygraph to screen applicants—a shortcoming he hopes will now be rectified.

He also called for a crackdown on “work-time abuse” by staffers who fail to put in a full 40-hour week for which they’re being paid. In the interview, Remington said the extent of this abuse remains unclear. “It’s a problem we still need to look at,” he said.

The department’s 16 juvenile camps, housing 1,300 clients, were another key target for reform. This area is particularly important because the camps are the subject of an agreement with the U.S. Department of Justice, which is monitoring, among other areas, allegations of child abuse and poor mental health treatment.

Remington said all but three camp directors were interviewed at length and appear, as a group, to be “capable of effectively managing” their responsibilities. The problem, Remington said, is that they’ve “been demoralized as their roles have been shifted from leaders to passive followers.” He said they “feel stripped of the authority to operate their camp or manage their staff” when their decisions are “rescinded without explanation” from higher-ups.

Remington said this problem can be quickly corrected by simply restoring authority to these managers.

To save money and improve services, Remington recommended moving the camps’ reception and assessment units from the Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall in the San Fernando Valley to Challenger Memorial Youth Center, a complex of probation camps in Lancaster.

Despite the deep troubles at Probation, not all of the news is bad, Remington said. Some reforms have already started, and many in the department want to improve. “People here are tired of reading about the ‘dysfunctional or beleaguered Probation Department’ and they want to make a change.”

Posted 8/25/10

Supervisors back probation reforms

June 29, 2010

Standing along a back wall in the Board of Supervisors’ hearing room, the newly appointed chief of the Probation Department almost smiled as his bosses unanimously passed three measures aimed at restoring integrity and accountability to the troubled agency.

Standing along a back wall in the Board of Supervisors’ hearing room, the newly appointed chief of the Probation Department almost smiled as his bosses unanimously passed three measures aimed at restoring integrity and accountability to the troubled agency.

“I thought the vote was very encouraging,” said Chief Probation Officer Donald Blevins, who has little to smile about these days. “This is another example of the message I continue to get from [the Supervisors]—that we brought you in to fix a huge problem and we want to give you the tools to get the job done.”

The motions, which passed quickly and without discussion, had been tabled after Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas abstained from voting on them last week, leaving the short-handed board one vote short of the three needed for passage. Although the supervisor did not explain the move, the next day he called on the Justice Department to broadly oversee the Probation Department, saying the problems were too entrenched for the new management team to fix—a view not shared by his colleagues.

On Tuesday, Ridley-Thomas voted to approve the three motions. Supervisor Don Knabe was absent.

In recent weeks, the 6,000-person Probation Department has been rocked by disclosures that, among other things, employees used county credit cards to buy electronics goods that dozens of employees accused of misconduct escaped discipline because the investigations ran too long and that the department cannot fully track $79 million allocated by the Board of Supervisors largely to hire personnel.

Two of the motions passed Tuesday were co-authored by Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky. One, written with Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich, will expand the responsibilities of the Office of Independent Review to include oversight of the Probation Department’s internal investigations. For nearly a decade, the OIR’s work has been largely confined to monitoring the operations of the Sheriff’s Department.

The second motion—this one co-authored with Supervisor Gloria Molina—directs the CEO, County Counsel, personnel officials and others to explore within 30 days how Blevins could, under Civil Service rules, begin hiring more managers from outside the Probation Department—a break with current practices.

The third motion, authored by Supervisors Antonovich and Knabe, attempts, among other things, to insure that that no employees in the future escape discipline because of unnecessarily long internal investigations and that probation officials responsible for such lapses in the past be held accountable.

In an interview, Blevins said that, thanks to the passage of the motions, he was “pretty satisfied that we have the right tools we need now.” He didn’t rule out, however, the possibility that he’ll return to the Board for help in solving future problems.

Moving forward, Blevins stressed the need for building a management team of about four to eight people, including insiders and outsiders, that can hit the ground within 60 days. “It’s important,” he said, “to have a management team that’s loyal to you.”

He said he also wants to quickly initiate discussions with the Office of Independent Review so its attorneys can start providing the kind of tough oversight that will reduce bottlenecks that have plagued the department’s internal disciplinary system. He praised a recently completed OIR study of the department’s disciplinary lapses, saying it offered “the same conclusions I would have come to.”

On Tuesday, Blevins also presented the supervisors with a status report on the management and administration of the department, focusing on areas where the department already has begun to confront deficiencies and impose tighter controls.

Blevins said, for example, that the department is now attempting to track where each of its employees currently is assigned to work. This surfaced as an embarrassing problem after probation officials were unable to tell the board exactly how the $79 million allocated for new hires had been spent.

Blevins also said in his report he is determined to increase the department’s operational and financial efficiency by making sure staffing ratios are appropriate and that the department’s network of juvenile camps are not housing charges who would benefit from less costly community-based alternatives.

Still, despite the many problems facing his department, the well-respected probation chief sounded a positive note.

“Although there are departmental practices and procedures which have developed over many years and are within a departmental culture that is by nature resistant to change,” he said, “such resistance can be overcome as many staff and managers appear to be supportive of change to improve the Department.”

Two additional reports are scheduled to be delivered to the Board of Supervisors next month. One is an assessment undertaken by Chief Deputy Cal Remington and the other is a report by county-hired consultants on the juvenile probation camps.

Posted 6/29/10

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink