Top Story: Public Safety

Ready or not, here they come

August 26, 2011

With the clock ticking, a multi-agency panel in Los Angeles County has approved a plan to confront a “monumental” shift in California’s criminal justice system, one that forces the county to supervise thousands of newly released state inmates and incarcerate thousands more in its strained jail system.

With the clock ticking, a multi-agency panel in Los Angeles County has approved a plan to confront a “monumental” shift in California’s criminal justice system, one that forces the county to supervise thousands of newly released state inmates and incarcerate thousands more in its strained jail system.

Passage of the complex plan by the Community Corrections Partnership was required under a new state “realignment” law pushed by Gov. Jerry Brown and aimed at reducing California’s prison population while narrowing the state’s budget deficit. On Tuesday, the CCP’s plan goes before the Board of Supervisors, where it can only be rejected by a 4/5 vote.

Supervisors had lobbied hard against the state’s realignment law. They argued that Brown and the legislature were simply shifting the state’s burdens to California’s hard-pressed counties, with little regard for the financial implications or public safety risks. In fact, the state has committed to funding only the first year with a $112-million block grant and $8 million in start-up funds.

“This is going to be a tragedy for justice in our county,” CCP member Dist. Atty. Steve Cooley said Wednesday before casting the sole vote against the realignment implementation plan. “It’s predictable, it’s inevitable.”

The reality is that not even a unanimous rejection of the plan would have blocked or delayed implementation of the new law, known as AB 109.

Beginning October 1, the first flow of newly released state prisoners will begin arriving here and in counties across the state, where they’ll be supervised by local authorities rather than state parole officers. Under the state’s realignment program, only inmates convicted of non-violent, non-serious, non-sexual offenses will be placed under county supervision.

In Los Angeles County, that number is expected to hit 9,000 by June, swelling to as many as 15,000 in the second year. Taking the lead in their post-release supervision will be the county’s Probation Department, despite a highly publicized and contentious bid by Sheriff Lee Baca to assume that role.

Already, inmate files have begun arriving for pre-release review by probation, mental health and other designated officials. The goal is to make sure each parolee is provided with the necessary oversight and programs for rehabilitation. The process also is intended to weed out inmates who should have been exempted from the program because of serious or violent criminal histories or because they’d been earlier designated by corrections officials as “mentally disordered offenders.”

Inmates participating in “post-release community supervision,” who’ll be freed from 33 state prison locations, will be given $200, with orders to report to their designated locations within two business days. Despite the expressed fears of the Sheriff’s Department, the state says that only 2% of this type of inmate population has historically failed to show up for parole orientations within five days of their scheduled appearances.

Once they arrive at their assigned locations, a more thorough evaluation will take place, including risk assessments and “behavioral health screening.” Each supervised person will receive a “risk level determination” of Tier I (high), Tier II (medium) and Tier III (low).

Community-based organizations will be tapped to provide such services as substance abuse treatment, job training and other assessed needs. In the short term, because of time constraints, only organizations with existing county contracts will provide services. But longer term, the county will soon request proposals so more organizations can participate and specific service gaps can be filled.

One of the trickiest elements of the plan—described as a work in progress—will be to determine the precise mental health histories and needs of the new charges. Initial prisoner packets will include no detailed medical information. Talks are underway with state corrections officials to provide mental health records directly to the county’s Department of Mental Health but cost and confidentiality issues have yet to be resolved.

Post-release supervision represents just one component of the realignment challenges. The bill’s most controversial and daunting requirement changes the very nature of California’s county jails and, according to some criminal justice officials, poses the highest potential risk to public safety.

Under the legislation, defendants convicted of non-violent, non-serious, non-sexual crimes will no longer be sentenced to state prison unless they have prior violent or serious convictions or are required to register as sex offenders. Beginning in October, this class of defendants will be serving their time in county jail at an estimated rate of 7,000 a year. That means Sheriff Baca will have to further juggle and prioritize who stays behind bars and who’s freed on work release, GPS monitoring or other “community based alternatives.” Thousands of more beds, depending on funding, also would have to be opened at various jail facilities.

District attorney officials and others worry that, because of overcrowding, this new class of inmate will inevitably be sprung early and end up back on the streets, committing crimes at a time when, in the past, they’d be sitting in state prison cells.

In a section of the CCP implementation report titled “jail population management,” the authors state that the wholesale transfer of such responsibilities from the state to Los Angeles County “is monumental and will not only mark a challenge for the Sheriff’s Department but also the District Attorney, the Public Defender, the Probation Department, the Department of Mental Health, the Department of Health Services, the Superior Court, and all municipalities.”

But there are others who say they’re ready and anxious for the opportunity to help the returning inmates get fresh starts. For the past two months, representatives of community and faith-based groups have shown up at CCP meetings, where they’ve urged that a greater emphasis in the discussions be placed on rehabilitation rather than incarceration. And Wednesday was no exception.

As one speaker put it: “Let’s take a mess and turn it into a blessing.”

Posted 8/26/11

Reaching kids before spark explodes

August 3, 2011

In the summer of 2008, three teenaged boys climbed a hill with a half-dozen big firecrackers. It was July in Pasadena and the slope was tinder dry. Later, they would say that they weren’t thinking about fire hazards as one pulled out a cherry bomb and let another one light it—they just wanted “to make a lot of noise.”

In a backyard patio not far from the hillside, a neighbor heard an explosion and then saw flames rising. Next door, a 911 caller reported yelling and “high-fiving” as the boys ran away. The flames were out of control within minutes; they consumed five acres of the Angeles National Forest before firefighters stopped them. Two of the three juveniles were subsequently convicted of arson.

Though the harshness of the conviction was unusual, the incident wasn’t. According to the Burn Institute in San Diego, minors account for more than 50% of all arson arrests in the nation. A 2010 report for the National Fire Protection Association found that in the year of that Pasadena incident, children playing with fire started some 53,500 conflagrations, causing some $279 million in property damage, 70 civilian deaths and 910 injuries.

That’s why a modest $148,760 grant approved this week by the Board of Supervisors is being welcomed at the Los Angeles County Fire Department. Earmarked for a special program in intervention and one-on-one counseling of juvenile fire setters, it will increase by several orders of magnitude the number of county firefighters who are trained to deal with an ongoing hazard, particularly in fire-prone communities.

“It’s a program we’ve always had, but our ability to train firefighters in these skills has ebbed and flowed over the years,” says Chief Deputy John Tripp, who commands the department’s emergency operations. At the moment, Tripp says, the department has “maybe a dozen” firefighters who have received the special training necessary to intervene when a fire turns out to have been caused by a minor.

“That limited a number of people is of questionable effectiveness when you’re trying to protect 4 million people,” he says.

Administered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the grant—which will be matched by a $37,190 contribution from the county—will allow the department to offer 32 hours of special training to 66 firefighters sometime early next year.

As Juvenile Fire Setter Intervention specialists, those firefighters will then be able to make the necessary assessments when a child starts a fire, bringing a child and his or her family in to the fire station for one-on-one counseling and education or, in more serious cases, referring the child for more extensive professional treatment.

Most fires are accidental, Tripp says, and fires started by children are usually the result of “naïveté about the danger.” But playing with fire can also be a sign of psychological problems.

“The statistics show that without intervention, a lot of juvenile fire-setters will start fires again,” says Heidi Oliva, a civilian administrative services manager for the department who helped shepherd the grant.

Oliva has firsthand experience with the risks of juvenile fire setters. In October, 2007, she and her husband had to flee their Santa Clarita home with a 4-year-old and an infant when stiff Santa Ana winds swept the Buckweed Fire down from Agua Dulce. The fire destroyed 38,000 acres and 21 homes.

Its cause? A 10-year-old child playing with a pack of matches. The child eventually moved and prosecutors chose not to file charges; authorities must prove intent to cause harm in order to charge someone with arson, and that can be difficult with young children.

But the lessons of that fire and others are instructive, Tripp says.

“Fire is a natural foe and a danger to everyone in our community all the time, and if we can step in at the start of a dangerous behavior, we need to do that. Otherwise, a small situation can become a larger, more dangerous one.”

Posted 8/3/11

Homeboy counting on a comeback

July 12, 2011

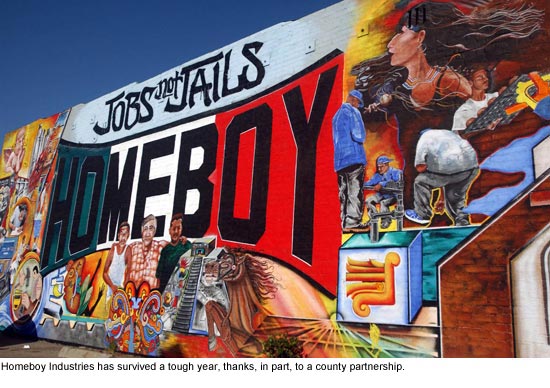

Last May, Homeboy Industries was in serious peril. The recession and a costly expansion had crippled the renowned gang intervention program financially. Three-quarters of its staff had been laid off and Father Gregory Boyle, Homeboy’s Jesuit founder, was relying on volunteers just to keep the doors open.

What a difference a year can make.

With a push for federal funding, a barrage of new initiatives, and—crucially—a key $1.3 million contract from Los Angeles County, “we’re still struggling, but we’re back on our feet,” says Veronica Vargas, Homeboy’s chief operating officer.

Not that they’re unscathed. The organization is accepting only about half the in-house job trainees it used to. Health insurance has been cut for trainees in its Chinatown headquarters. The waiting lists for tattoo removal, mental health care and other services are so long, “we’re doing triage,” says Vargas.

But in the past year, Homeboy, which says it helps 12,000 gang members a year with educational, mental health, legal and job training services, has not only dramatically ramped up its business, but also begun to see the fruits of a county-funded initiative to objectively measure the success of its programs.

“I’ll be blunt—so far, it’s not at all what I expected,” says Jorja Leap, one of two UCLA School of Public Affairs scholars who have been monitoring Homeboy both for a separate longitudinal study and as part of the county’s 9-month contract.

Since September, at the county’s behest, Homeboy has been providing job counseling and development, mental health care, tattoo removal and other services for 665 probationers and other high-risk individuals between the ages of 14 and 30. This week, Leap and her colleague, Todd Franke, submitted the second of three progress reports to the county.

Six months into the contract, Leap says, demand has been strong—and growing, particularly among county probationers and parolees under 30. Early figures show that about 100 county clients per month have volunteered for tattoo removal, and about 300 a month have been taking advantage of Homeboy’s employment counseling services. Another 150 or so each month have attended life skills, GED, 12-step and other classes.

Those numbers—and that word “volunteer”—are important because they reflect the extent to which the county might, over time, reduce duplication between Homeboy and its own gang re-entry programs.

Cal Remington, chief deputy of the county’s Department of Probation, says the reports have been encouraging so far, and Homeboy’s success is well-known, but savings ultimately could be limited.

For example, he says, most Homeboy programs are based on the belief that people don’t change unless they want to, and the organization “wants people to come on their own.” But probation and parole are, by their nature, involuntary. Many probationers and parolees do seek out Homeboy, he says, but unless the entire county caseload volunteered, some would still require county-run re-entry programs.

For example, he says, most Homeboy programs are based on the belief that people don’t change unless they want to, and the organization “wants people to come on their own.” But probation and parole are, by their nature, involuntary. Many probationers and parolees do seek out Homeboy, he says, but unless the entire county caseload volunteered, some would still require county-run re-entry programs.

“I think they provide a real service that benefits the county,” he says, “but we’re interested in finding out how many [probationers] voluntarily take advantage of that, and then how they’re doing in the community.”

Additionally, the report has tracked a smaller cohort of job trainees whose positions are also funded under the county contract.

So far, Leap says, about 50 former gang members, two-third of them male, have cycled through those 30 trainee positions. And though gang populations nationally have a 70% recidivism rate, she says, only three of the county’s Homeboy trainees have been re-arrested and none have gone back to prison so far.

On the other hand, she says, one of the 50 has now entered college, four have gone on to full-time jobs with employers outside Homeboy, about 20 have worked their way up to employment at one of Homeboy’s various businesses and another 22 or so are continuing to progress through the program.

Leap cautioned that the numbers are preliminary. And, she says, the data has not yet come in for a planned comparison with retention and recidivism rates in two county-run gang re-entry programs.

“But,” she says, “you don’t need a Ph.D to tell you that these are phenomenal, phenomenal results.”

“This is why I can’t wait for the county to see how well this program works,” exults Vargas. “Nobody back in prison? That’s huge.”

Although four outside placements and a college enrollment may not sound like much after six months, she says, just sticking with the program is an achievement for many gang members.

One young man profiled in Leap’s report had come to the Homeboy program after an 18-month stint in state prison on an armed robbery conviction. The son of a drug-addicted mother and absentee father, he had grown up in a 3-bedroom apartment shared by 30 people in the Nickerson Gardens Housing Project.

He had thrived as a Homeboy trainee, the report says, and was working with young adults just out of probation camps within three months of his arrival. But his family’s gang ties were a constant source of conflict.

“Some family members would openly mock his efforts, while other relatives would pressure him to get back involved in the streets and the gang life style,” the report says. For a while, the young man slept in his car to escape the pressure, but his struggle has been apparent.

“He continues to be an excellent worker,” according to the report, but “he has not kept all his appointments and seems very conflicted about gang involvement.”

It’s a common pattern, says Vargas. Indeed, one of the county-funded trainees—a 22-year-old who had diligently worked his way up to an office assistant job at Homeboy—was shot and killed last month at a late-night party in Hollywood during what authorities said was a gang-related argument.

According to Leap’s report, the vast majority of Homeboy’s clients are county probationers and parolees who are struggling to regain their footing. Many have spent years in and out of probation camps where, the report notes, they missed out on learning even such basic life skills as how to look employers in the eye and offer a firm handshake.

“Says Vargas: “You can’t rehabilitate someone in six months when they’ve been raised all their lives in violence.”

This, she says, is why she hopes the county will consider renewing its relationship with Homeboy when the current contract expires at the end of next month.

That may not be easy, given the county’s own struggles.

“As you know, we have our own deficit to deal with,” says Sheila Williams, who helps oversee the county’s public safety agencies for the Chief Executive Office. But, she adds, so far, there have been no complaints about Homeboy’s performance and “discussions are continuing.”

Meanwhile, Vargas says, Homeboy has been hustling.

The organization has won a federal grant that will to bring in about $400,000 a year for the next three years. Father Boyle has been on a book tour, promoting his acclaimed memoir, “Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion” ; those proceeds all go to Homeboy as well, Vargas says.

Ralph’s markets began offering Homeboy’s signature chips and salsas in its supermarkets nationally this year, and another initiative is promoting Homeboy products at farmers’ markets.

The conviction of KB Home’s former chief executive, Bruce Karatz, on charges that he lied about backdating stock options resulted in an unusual sentence in which Karatz—who in the run-up to his trial had already pledged $1.1 million to the organization—would bring his experience and contacts to bear as an unpaid Homeboy consultant. Vargas says they’ve only received about $200,000 of the pledge so far, but credits Karatz with the nailing the Ralph’s salsa deal in just a few phone calls after years of conversations.

And City Hall will soon be getting a new Homeboy café.

“We’re doing everything we can think of,” Vargas says. “We have to. You should see our waiting list.

“There are hundreds of people coming through our doors every month, asking for employment, and right now, we can’t provide it for them.”

Posted 5/5/11

Practicing for peril in paradise

April 28, 2011

Topanga Canyon is one of the most storied and bucolic nooks in Los Angeles County. It is also one of the most fire-prone.

Topanga Canyon is one of the most storied and bucolic nooks in Los Angeles County. It is also one of the most fire-prone.

The only way in or out is via a winding and often-gridlocked blacktop. Gardens and yards intertwine with flammable chaparral and tinder-dry wildlands. Past fires have shown over the years that the canyon could burn end to end in less than half the time it would take for its 12,000 inhabitants to get to safety.

“There’s a reason we call Topanga the ‘Perilous Paradise’,” says Maria Grycan, community services liaison for the Los Angeles County Fire Department.

“It’s one of the most beautiful places to live and play, but with that beauty comes a great deal of danger in terms of wildfires.”

This is why Topanga has adopted one of the more aggressive strategies in Los Angeles County when it comes to drilling for fire safety: On May 7, for the second year in a row, residents will practice evacuating the entire town.

Sometime in the morning, Topangans will be roused by the sort of “emergency” phone call they could expect in the event of a fast-moving brushfire. If they’ve done their homework, they’ll know what to do next; if not, they’ll have plenty of firefighters around to help them.

Either way, within a few minutes, if all goes as planned, thousands of canyon dwellers will show up and sign in at an assortment of designated addresses where they could survive a wildfire if the canyon’s escape routes were blocked or congested.

Think of it as a massive dry run for an ongoing threat, but don’t call it a fire drill, says Grycan.

“Drills are just to get people out of a burning building,” she says. “This is way beyond that. We’re dealing with a whole canyon here.”

The exercise, which drew nearly 1,100 participants last year, is considered a crucial link in Topanga’s emergency planning. With the serpentine Topanga Canyon Boulevard as the only main road in or out, Topanga is vulnerable to bumper-to-bumper traffic even on better days. Authorities have estimated that evacuating the whole community could take close to six hours—enough time for the town to burn more than twice over, says Grycan. “A fire that started on the north end of Topanga could get all the way through town and to the coast in less than two and a half hours.”

Also, despite its rural reputation, some parts of Topanga are densely populated.

“We live in the Fernwood area, which has so many trees and so many houses that if a fire came to Fernwood, it would be like Armageddon,” says Debra Silbar, who took part in last year’s drill with her then-14- and 9-year-old children in tow.

So at the county’s behest, the unincorporated community has sought in recent years to become a model for preparedness, splitting itself into nine “tactical zones” for easier evacuation, publishing a “Topanga Disaster Survival Guide”, designating safe – or at least survivable – meeting points throughout town for times when evacuation won’t work and educating residents with an annual Topanga Safety Week and evacuation exercise.

This year’s Safety Week will begin May 2 with a series of daily activities to promote awareness. Grycan says a workbook will be mailed to every household to help locals freshen their knowledge. Topanga Elementary School will drill on Wednesday, and county firefighters will demonstrate firefighting techniques.

The week will culminate with the community-wide evacuation exercise from 9 a.m. to 11 a.m. on Saturday, May 7. Led by the county fire department, the drill will involve an array of local law enforcement, first responders and government and community volunteer organizations, says Grycan. “The premise is, there’s a fire, the road is in gridlock, evacuation is not an option. Where do you go?”

The exercise, she says, will help residents remember the answers to that question.

“Our first preference in the event of a fire is that people leave early enough that they can get out of the canyon,” says Grycan. “Plan B is, if you can’t get out, then get to a safety area. And Plan C is, if you can’t do Plan B, then at least get to a neighborhood survival area where, say, a fire is more likely to blow over you, or where, if you were caught in a fire, you’d be more likely to survive.”

Additionally, she says, the drill will allow local emergency workers to practice their internal coordination, and will offer a chance to test Alert LA, the mass notification system that they were unable to use last year. Grycan says a last-minute glitch forced emergency workers to use a fallback notification system that only allowed notification of residents with landlines. As a result, many Topangans failed to get the reminder, particularly in less densely populated areas of the canyon.

“We were one of the evacuation sites but nobody showed up at our place,” says Patricia Moore, whose 6-acre Eden Ranch has been designated a neighborhood survival area because of its flat terrain and ample access to water. “There were two people here to take names, and they just kind of sat there, which was kind of sad.”

Pat MacNeil, former chair of the volunteer Topanga Coalition for Emergency Preparedness, says she expects turnout to be even better this year.

“With all the disasters in Chile and Japan and Louisiana, people are becoming more aware of the fact that they have to take care of themselves,” she says.

Meanwhile, locals like Silbar say they are looking forward to reprising their civic duty.

“Last year, I put my kids in the car, we drove down and checked in and it literally took one minute,” she says. “It was a simple way to help out the community. But we’ve also had to evacuate before, and we know how crazy things can get in those situations. Drills like this, I think, help our kids realize what happens when there’s an emergency in the canyon, and will give them a better sense of control.”

Posted 4/28/11

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink