Top Story: Public Safety

Ex-jail captain feeling the heat

July 12, 2012

Inside Men's Central Jail, where allegations of brutality led to the creation of a commission on jail violence.

Eight months ago, amid mounting reports of brutality in Los Angeles County’s jails, Sheriff Lee Baca would offer only a few words of explanation about why the former captain of the Men’s Central Jail had been placed on leave and sent home.

“I’m looking into a few matters,” the sheriff said.

In recent weeks, some of those matters have come into very public view.

Captain Daniel Cruz has unhappily found himself front-and-center in an investigation by the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence, a high-powered panel created by the Board of Supervisors to, among other things, “restore public confidence in the constitutional operation of our jails.”

During the commission’s last two hearings, Cruz has been accused by former and current members of the department of failing to hold deputies accountable for significant levels of serious force against inmates. According to testimony, scores of brutality investigations languished over the years in file boxes and desk drawers, undermining the department’s ability to track abusive deputies. One witness, a former lieutenant, said he was repeatedly told by Cruz not to spend too much time attacking the backlog that had been growing under the captain and his predecessors.

In an interview, Cruz insisted that he’s undeservedly being vilified for reasons that have more to do with personalities than with facts.

“I’m in front of the firing squad right now and everybody is taking a shot at me,” the 33-year department veteran told a writer for Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s website. “I have to sit back and listen to everybody saying what a schmuck I am. If I was reading what’s in the papers, I would think this guy wasn’t doing his job. But that’s far from the case. It’s not a true representation of my character. I worked very hard to reduce force at CJ [Central Jail] and the numbers show that I did.”

Cruz served as the Men’s Central Jail captain between 2008 and 2010. He was transferred to the department’s Transit Services operation before being placed on paid leave. So far, he has not appeared before the 7-member commission, whose members include retired judges, the current Long Beach police chief and the one-time spiritual leader of First AME Church. But Cruz said he wants to share his side of the story with investigators. “I’d like to get my turn at bat,” he said.

Also emerging as a central figure in the commission’s inquiry has been the man who reportedly favored Cruz for the job, Undersheriff Paul Tanaka. He, too, has been criticized in testimony for allegedly creating a culture that fostered excessive force by openly deriding the work of internal affairs investigators and by ordering supervisors to, among other things, “coddle” jail deputies.

For his part, Tanaka, the department’s No. 2 man and the mayor of Gardena, has so far remained quiet, declining requests for comment. He and Baca are scheduled to testify before the commission on July 27, a hearing that’s certain to generate considerable interest within a department that has been rocked by the ongoing controversy over its management of the county’s vast jail system.

By all accounts, conditions have improved markedly in the jail as Baca has moved to intensify oversight and accountability. He has installed new leadership there and created a commander-level task force that briefs him regularly on jail operations and trends. Incidents of significant force have fallen dramatically.

Still, the commission was given a mandate by the Board of Supervisors to look back at the possible root causes of the problems that led to the panel’s creation last October and offer recommendations for the future. Along the way, it has generated a number of disclosures about the policies and people who have governed jail operations.

Beginning during a commission hearing in mid-May, it became evident that panel investigators—many of them former federal prosecutors working pro bono—had begun to believe that specific individuals may have been as responsible for a rise in serious inmate injuries as any structural or systemic problems. During that session, both Cruz and Tanaka were criticized by two retired officials of the jail for allegedly undermining efforts to break-up deputy cliques and of failing to hold jailers accountable for unnecessary force.

That theme continued last week with testimony from an active-duty captain, Michael Bornman, a 30-year veteran who currently oversees educational programs in the jail. Obviously uncomfortable as he was questioned by the commission’s executive director, Bornman described his testimony as “the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my entire life.” Commission staff say he was encouraged to appear before the panel by Baca himself.

Bornman recalled instances that he said raised alarms in his mind about Cruz’s views on deputy violence—both on and off the job. One of those incidents involved the beating by several deputies of an inmate near a jail medical clinic, which was captured on a newly installed video camera about which few knew. According to Bornman, the prisoner was punched, kicked and repeatedly knee-dropped by one particularly bulky deputy. The inmate, he said, suffered broken ribs.

If that wasn’t disturbing enough, Bornman said, he was taken aback by what he contended was Cruz’s reaction. “I see nothing wrong with that use of force,” Bornman quoted the captain as telling a group of jail supervisors, who’d gathered to watch the video. Ultimately, an internal investigation—with Bornman’s active participation—called for the firing of one deputy and the suspension of two others.

Bornman also recounted a speech he said Cruz gave in 2009 to a banquet hall filled with jail deputies during their annual holiday party. “What do I always tell you guys?” Cruz reportedly asked the crowd. “Not in the face!” they responded in unison—an allusion, Bornman said, to how to strike an inmate without leaving tell-tale marks.

But Cruz, in the interview, disputed Bornman’s account, saying that his former subordinate offered a sinister and incomplete version of the event.

Cruz said he typically ended his remarks to the troops with three admonitions: “Don’t drive drunk. Don’t put your hands on your wives and girlfriends and don’t hit people in the face.” Cruz said that last warning had nothing to do with hiding the signs of a beating. “When you hit someone in the face, you can end up injuring yourself and the inmate,” he said. “It’s generally an ineffective tactic.”

Whatever the case, Bornman said he was so put off that he decided to sit out the following year’s ill-fated party at the Quiet Cannon in Montebello, where deputies from different floors of the Men’s Central Jail squared off in a wild parking lot brawl. When Montebello police arrived, Cruz assured them there was nothing left to investigate, that all was resolved. In the end, six deputies were ordered fired.

Said Bornman: “I could have predicted what happened there.”

As in the commission’s May hearing, panel members explored the relationship between Cruz and Tanaka. Under questioning from one commission member, former U.S. District Judge Robert Bonner, Bornman said Cruz “made it very clear that Mr. Tanaka had helped him.” In fact, Bornman quoted a defiant Cruz as insisting that he still reported to Tanaka, who was no longer even in charge of custody operations.

Although Tanaka is largely unknown to the public, he is powerful presence within the Sheriff’s Department, second in command to the elected Baca. He receives high marks from many in the department. But he’s been criticized during the commission’s hearings, which have dealt only with a limited part of his broad portfolio. Among other things, he’s been called to task for allegedly brushing back supervisors in the jail and elsewhere when they’ve tried to rein in deputies they believe are acting too aggressively.

On Friday, for example, the commission released a 2007 memo that memorialized a visit by then-Assistant Sheriff Tanaka to the Century Station, an area of high gang activity. The memo was written by the station’s captain at the request of the region’s field operations commander. In it, the captain quotes Tanaka as warning captains and supervisors not to be “hasty” in filing complaints, or “cases,” against aggressive deputies, “who should function right on the edge of the line.” Tanaka said such actions can have “a negative impact on his performance and personal life.”

The memo went on say that Tanaka does not like the Internal Affairs Bureau and then recounted this promise from the assistant sheriff: “He said he would be checking to see which Captains were putting the most cases on deputies and that he would be putting a case on them.”

Posted 7/12/12

These jailhouse lawyers work for us

June 13, 2012

Former federal prosecutor Richard E. Drooyan is leading the investigation of deputy force in the county's jails.

When it comes to police scandal and reform, attorney Richard E. Drooyan has found no shortage of opportunity in Los Angeles.

A former high-ranking member of the U.S. Attorney’s Office, he served on the Christopher Commission after the Rodney King beating and helped lead an independent inquiry into corruption by anti-gang officers in the LAPD’s Rampart Division.

Now, he’s back, this time as general counsel to the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence, a panel created in October by the Board of Supervisors to investigate alleged brutality and management failures in the county jail system. The commission is packed with marquee names in law enforcement and legal circles. But it’s the lesser-known Drooyan who’s largely orchestrating the historic effort—with the quiet help of some of Los Angeles’ most prestigious law firms.

Drooyan is drawing on a model that dates back to the Christopher Commission, one not widely known beyond Los Angeles’ legal community. Today, as in the past, he’s drafted an army of high-powered lawyers to conduct every facet of the investigation, assigning each with responsibility for a specific area of inquiry. Those attorneys, in turn, have dipped into the ranks of their own firms.

In all, some 50 lawyers, representing ten firms, have been pressed into action—without a single billable hour among them.

“Fortunately, there’s been a history of very talented lawyers in the town’s top firms who’ve been willing to devote pro bono hours to these kinds of investigations,” Drooyan said from his office at Munger, Tolles & Olson. “The reality is, you need experienced people who can devote a lot of time and energy but you don’t have the budget to pay them. If you were to add up the final billable hours for the jail commission, it would be north of seven figures.”

The payoff, so far, has been substantial. This unsung cadre of legal firepower has identified and interviewed scores of witnesses, reviewed hundreds of documents and, in a series of public hearings, elicited dramatic testimony suggesting that the department’s second-in-command contributed to a climate in which jail deputies used unnecessary force.

The Commission’s chair, retired federal judge Lourdes Baird said the legal team has become “an integral part of our commission’s efforts” and “exemplifies the best of public service in our legal community.”

One of the recruited attorneys is Nancy Sher Cohen of Proskauer Rose, who calls herself a “worker bee for the commission.” Like Drooyan, Cohen also served on the Rampart panel. “Most of us tend to work on corporate litigation,” she explained. “Of course, you love your clients but this has a social justice piece that makes it very special.”

Bert Deixler, who served with Drooyan on the Christopher Commission and has been tapped for the jail study, says the unique investigative approach also provides newer attorneys with the experience of having societal impact while serving with seasoned law veterans across the city, a rare opportunity in a highly structured business.

“You take some young stars in your firm and say, ‘Here’s a chance to pay it forward.’ There’s a sense for all of us that this is part of what lawyers are supposed to do. It’s not just about collecting money,” says Deixler, a former member of the U.S. Attorney’s Office who’s now a partner with Kendall Brill & Klieger.

To get a feel for the job at hand, the recruited lawyers toured the troubled Men’s Central Jail on the edge of downtown, built mostly during the early 1960s. With more than 4,000 inmates packed into dark cells, it’s become the primary focus of the commission’s inquiry.

“For those who hadn’t seen it before, they came away from the experience feeling speechless,” said the commission’s executive director, Miriam Krinsky, who went on five of the trips. “It can’t help but hang with you.”

The attorneys assembled by Drooyan are a formidable group. Many are former federal prosecutors—skilled investigators with experience in analyzing data and coaxing reluctant witnesses to come forward. Already, their effectiveness has been on display during a series of headline-generating hearings during the past several months.

This was particularly true on May 14, when Drooyan presented as witnesses three retired jail supervisors. Their testimony went beyond the more familiar allegations of brutality and suggested that a series of moves by a top Sheriff’s Department manager undermined jail supervisors and led to higher levels of excessive force.

They described a culture in which longtime jail deputies—who, like some behind the bars, dub themselves OG’s, short for “Original Gangsters”—seemed to carry more clout than their bosses. Retired Sergeant Daniel Pollaro told of insubordinate deputies changing work assignments that their supervisors had created to break up “cliques” on floors throughout Men’s Central Jail. Retired Lt. Alfred Gonzales, meanwhile, recounted, among other things, the resistance he met while patrolling those floors in an effort to keep deputies in line and out of trouble, a practice not embraced by his predecessors.

But the testimony that raised the most eyebrows was Gonzales’ account of a meeting that then-Asst. Sheriff Paul Tanaka convened with jail supervisors in 2006, which followed an unusual closed-door session he’d held with complaining deputies.

“You guys are a bunch of dinosaurs,” Gonzales quoted Tanaka as saying. “Your supervisorial skills are antiquated.” According to Gonzales, Tanaka instructed the supervisors to “coddle” the deputies and to “stay off those floors and let those deputies do what they have to do.”

“The chain of command was totally broken,” Gonzales testified.

Tanaka, now the department’s undersheriff, is scheduled to appear before the commission in late July, along with Sheriff Leroy Baca. Neither has commented on last month’s testimony.

By all accounts, one of the biggest challenges for this commission—like others before it—is not only to identify witnesses but also to get them to testify publicly.

Drooyan said that Gonzales and Pollaro agreed to testify because after spending much of their working lives in the Sheriff’s Department, “they genuinely wanted to see issues addressed that were of deep concern to them.”

Sometimes, though, it can be tougher, especially in eliciting cooperation from current members of the department.

“They feel their careers are on the line,” said Fernando Aenlle-Rocha, a former federal prosecutor who’s now with the firm of White & Case. “We don’t have subpoena power and we can’t immunize people—the kind of tools that are given to prosecutors. You can just use your persuasive skills.”

So far, according to a recent commission status report, more than 150 potential witnesses have been identified between the five investigative teams created to examine the jail system’s management and oversight, use of force, culture, discipline and personnel. Each team will write a chapter for the commission’s final report, which is expected to be issued in early fall after more hearings. The full commission has met nine times to date. A committee held its first community forum on May 30.

Executive Director Krinsky stressed that the Sheriff’s Department and the commission have been extremely cooperative with each other. “It’s not a ‘gotcha,’ ” she said.

Drooyan agreed, adding that Baca himself has personally assisted in the commission’s requests for information.

“Everybody,” Drooyan said, “wants to improve the jail.”

Updated: At the Decemember, 4, 2012, meeting of the Board of Supervisors, Drooyan was appointed to oversee implementation of more than 60 reforms recommended by the jail commmision in its final report, which was released in September. Click here to read it.

Posted 6/13/12

The Westside’s too “social” party scene

April 11, 2012

Police suspect that the movie "Project X" inspired the free-for-all parties in Pacific Palisades and Holmby Hills.

Talk about paradise lost.

While vacationing in Hawaii two weeks ago, a Pacific Palisades teenager learned from postings on his Facebook page that he was missing a party—at, gulp, his own house. The boy had unwittingly opened the door by letting his Facebook “friends” know that he and his family would be out of town.

“The father called us from Hawaii saying that something might be going on at his home,” recalled Los Angeles Police Officer Raymond Barron. That was an understatement. The house had been broken into and trashed by a crowd of drinking, partying young people, some of whom allegedly stole laptops and sound equipment. Eleven juveniles and 2 young adults were arrested.

Meanwhile, also on the Westside that same weekend, more than 500 partyers overtook an apparently vacant home in Holmby Hills after they’d been chased out of a house by police in Beverly Hills. Once again, word of the roving party had spread instantaneously through Twitter and other social media. It took nearly an hour for officers, who made numerous arrests, to clear the revelers who’d streamed into the quiet neighborhood “like a swarm of bees,” according to one resident.

Members of the LAPD’s West Los Angeles Area are, of course, no strangers to the occasional big, unruly party that might get going near UCLA or in large homes rented out for the night, said Officer Barron. But the two “flash mob parties” that occurred on the weekend of March 31 represented a troubling twist on the party scene, one that Police Chief Charlie Beck said requires some basic digital-age precautions. Perhaps most important: “If you’re going to be absent from your residence,” the chief said, “don’t put it on social media.”

In a “community alert” this week, the West L.A. station’s crime analysis detail said there appeared to be a link between social media-fueled parties and the release of “a particular movie.” In the most recent cases, the department has speculated that “Project X” may have served as inspiration. The movie, released in March, is about three friends who plan on becoming popular by throwing a raucous party that quickly escalates out of control.

Or as one blurb said of the movie’s plot: “A parent’s worst nightmare.”

Posted 4/11/12

Stopping a danger in the sand

April 4, 2012

Rescuers work feverishly to uncover a teen in Newport Beach who was buried for 30 minutes but survived.

The county’s new beach ordinance may have launched more than its share of wisecracks about allegedly outlaw Frisbees, but lifeguards say that at least one of the less-discussed changes could save lives—and that’s no joke.

The new law, which won final approval from the Board of Supervisors on Tuesday, bans the digging of holes deeper than 18 inches to avert dangers not widely known to beachgoers, said Los Angeles County Lifeguard Section Chief Mickey Gallagher.

“In my 40-year career, people have been badly injured and even killed as a result of sand tunneling,” he said. “This is about a safety hazard. It isn’t about little kids with plastic shovels digging a little hole in the sand.”

Last August, for instance, a teenager was buried alive for more than 30 minutes in Newport Beach. The then-17-year-old boy was building a tunnel when the sand collapsed around him. He survived, several feet below ground, only because he had managed to wiggle his head a little as the sand poured in around him, creating a slight air pocket that kept him alive long enough for emergency crews and bystanders to get to him.

Two months before that, in June 2011, a Northern California teenager on a beach outing with a church group was permanently disabled after being buried for more than 10 minutes when a sand tunnel collapsed on him.

In the same week, according to Los Angeles County lifeguard records, a 10-year-old boy in Manhattan Beach was rescued from a similar situation—only the top of the boy’s head was showing when the lifeguard found him. He’d been lying on his back in a hole, tunneling laterally, and had ignored a prior warning to stop digging because it was dangerous.

Nine months earlier, on Labor Day weekend, a 3-year-old toddler was taken by air ambulance from Zuma Beach to Harbor-UCLA Medical Center after she crawled into a sand hole that had collapsed on her, county lifeguard records show.

And two months before that, on July 25, 2010, an 11-year-old boy burrowing in Manhattan Beach was buried for five minutes as more than a dozen beachgoers, emergency workers and lifeguards tried frantically to extricate him. Lifeguards later said that the only reason they even located him was that his cousin had run, screaming, for help and one of his rescuers had glimpsed a patch of his blue swim trunks as they dug blindly under the sand’s surface. By the time he was pulled free, his lips were blue and he had stopped breathing; he vomited sand after a physician who happened to be at the scene administered mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

“Sand is really unstable, even when it’s hard-packed,” said Gallagher. “Every year, someone will try to dig a deep hole, or tunnel in from a steep berm after a high tide and get into trouble. Some people actually come down to the beach with big shovels, like you use in construction.

“People think they can make a tunnel or a cave, and to the untrained eye, the sand may seem fine because it’s wet. But without support, those tunnels will collapse, and sand is extremely heavy. And once someone is buried, it’s extremely hard to find them. And there’s no oxygen down there.”

The revisions to the beach ordinance make a number of other clarifications to the existing rules for recreation at the beach. Among other things, they make clear for the first time that Frisbees and footballs are allowed on the beach, albeit with certain restrictions. (Basically, you can do it anytime except when it endangers someone or a lifeguard deems it unsafe.)

Inaccurate press reports initially drew criticism of the changes, including the ban on digging, which was derided as meddlesome fun-killing. But Beaches & Harbors Director Santos Kreimann says lifeguards requested the digging restrictions so they could have legal backup in preventing a problem they’ve informally been guarding against for generations.

Beyond dangers to the diggers, Kreimann said, holes in the sand also create a hazard for emergency workers, who are jolted by them when they transport people with neck and back injuries.

“The bottom line is: Have a good time and play in the sand if you want to,” Kreimann said. “But don’t dig more than knee-deep, and if you make a hole, fill it back up.”

All that's left: the hole in Newport Beach where sand swallowed a 17-year-old boy. Photo/Los Angeles Times

Posted 4/3/12

Game-changer for a probation camp

February 14, 2012

The Malibu probation camp, one of the few to offer CIF sports, is getting a makeover. Photo/L.A. Daily News

Camp Vernon J. Kilpatrick has been rehabilitating troubled teens for generations. Now the famed Los Angeles County probation camp will be getting a rehab of its own.

This week, after nearly a year of analysis and study, the 50-year-old Malibu facility was chosen as the site of a $41 million makeover aimed at making the probation camp system less prison-like and more therapeutic. Underwritten by a $28 million state grant, the project will demolish the aging, 125-bed camp and replace its run-down infrastructure with a state-of-the-art rehabilitative compound.

“This is a real win for the kids who will go to that camp,” says Assistant Chief Probation Officer Cal Remington. “The architecture really does make a difference, and we’re hoping this will become a prototype.”

Camp Kilpatrick’s two residential dormitories will be split into four smaller cottages that will accommodate up to 120 boys, aged 15 to 18. Office and treatment spaces will accommodate counseling and small group meetings, and classrooms and medical facilities will be more intimate and safer. Parking, utilities and security will be updated. Even Kilpatrick’s frayed recreational facilities will be improved—it is one of the few camps in which teens have CIF sports as an incentive for good behavior, and a recreational multipurpose field is included in the grant plans. (This Los Angeles Daily News slide show took a look at the camp’s football team in 2006.)

Research has shown that small group settings are most effective in helping turn around the behavior of incarcerated adolescents, says Remington, but most of the county’s probation camps are built around big, institutional barracks and classrooms that subvert, rather than encourage, introspection and change.

The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted 4-1 Tuesday to replace Camp Kilpatrick, with Supervisor Gloria Molina casting the only “no” vote. The board’s action is the latest move in a longstanding plan to bring the county’s 17 probation camps into the modern era. The camp system houses some 1,300 young offenders, mostly in environments that feel, in many cases, like army outposts.

“All these camps are so old,” says Remington. “And they were all pretty much built according to the thinking of the early 1950s and 1960s, which was a military barracks-type scheme. And that architecture just does not work. When you put 105, 110 kids with school and gang issues into one of these big dorms, it’s just a recipe for more problems. There’s more competition, factions get created, you have gang problems. There’s just something about human nature that people get along better in smaller groups.”

Moreover, Remington says, the system’s operating costs have been soaring as the camps’ infrastructure has degenerated. An analysis by the county Chief Executive’s Office found that Camp Kilpatrick needs some $22.3 million worth of renovations beyond the $1.127 million the county spends, on average, to maintain it annually. Necessary repairs range from the camp’s faltering emergency response system to its gym, which has been yellow-tagged since the Northridge earthquake, and are so extensive that county officials determined it would be cheaper to simply tear it down and replace it.

“The camps are all old,” Remington says. “We just chose Kilpatrick because it was the biggest money pit.”

The state grant—authorized by the 2007 Juvenile Justice Reform Bill, which shiftedCalifornia’s non-violent juvenile offenders into county programs— will pay 75% of the cost of the remodel, with the county anteing up $12.4 million in matching funds. Remington says the department is aiming to have the new camp completed and opened by 2016.

The new design will allow camp supervisors to assign youths to cottages according to their various treatment needs and risk levels, and will create classrooms and treatment areas in which the camps’ charges can focus more easily.

During construction, however, the 100 or so adolescents now being housed at the camp will have to be relocated, and the supervisors instructed probation officials to report back in 90 days with a comprehensive plan. Remington says they will probably be moved in the short term to another camp in the system—one that probation officials hope will have room to continue the sports program.

Posted 2/14/12

A boatload of homeland security

January 10, 2012

Sheriff's officials are hoping to soon have a second terrorist-fighting boat patroling the waters off L.A. County.

Its crews have secured evidence from offshore pot busts. Its advanced sonar helped locate wreckage from a mid-air plane crash off the coast three years ago.

But mostly the Ocean Rescue II spends its days scanning for a threat that its crew hopes will never appear on any law enforcement blotter: the possibility that weapons of mass destruction might be smuggled into the massive Port of Los Angeles.

“This boat essentially provides homeland security for the entire L.A.County coast,” says Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Lt. Jack Ewell, who has worked on the 55-foot-long, super-high-tech vessel since its deployment in the port three years ago.

Paid for with a $2.25 million federal grant from the Department of Homeland Security and operated by a rotating 3-man crew from the sheriff’s special enforcement bureau, the Ocean Rescue II can scan ship hulls for traces of biological, radiological, chemical and nuclear weapons and can transmit the data to onshore labs in real time. Its sonar sees threats in the murkiest waters; its remote underwater vehicle can pluck bombs from ship bottoms and retrieve evidence 3,000 feet underwater.

“It’s pretty unique,” says David Gutierrez, vice-president of manufacturing at Willard Marine in Anaheim, which custom-built the vessel for the Sheriff’s Department. “It looks like just a standard boat with a lot of bells and whistles, but it’s a very important piece of equipment at the port.”

But the combination of all that technology and salt air is an ongoing issue: “You have to keep it painted, maintain the engines—to keep a boat like that working 7 days a week requires a lot of maintenance,” Ewell says.

“It’s like a patrol car,” agrees Gutierrez. “It has to always be ready to go.”

This, Ewell says, is why the sheriff hopes to bring in a backup with the help of a $3 million federal grant won by the department last year.

“A second boat will give us the capability to rotate vessels, or to have two boats in the water at the same time,” Ewell says.

It also will add to the sheriff’s already impressive counter-terrorism arsenal, which includes a radiation-detecting helicopter and a biological- and chemical-weapon-sniffing Labrador named Johnny Ringo.

At least eight of the 34 boats in the sheriff’s department fleet are assigned to the Special Enforcement Bureau, which includes the Homeland Security Division where Ewell works. Another dozen—including an offshore vessel with nuclear detection capabilities—patrol out of Marina del Rey or Catalina Island.

Backing them up, of course, are maritime forces from the U.S. Coast Guard as well as port-stationed boats manned by the Long Beach police, the Port of Los Angeles police and other law enforcement agencies.

The stakes are high, Ewell explains.

“It’s been estimated that an incident that shut down the port here would cost theU.S.economy $2 billion a day,” he says. “Forty percent of the nation’s imports come through here, and our coastal region is heavily populated. It would devastate the region if anything were to affect the port.”

So far, Ewell says, the boat’s daily scanning hasn’t uncovered any dirty bombs. (“Believe me, you’d know it if they did.”)

But it has been put to other uses. In April 2010, for instance, the sheriff’s department used it to help secure a large cache of marijuana from an isolated cove on Catalina Island where a smuggler’s boat had been stranded.

And in 2009, when two private planes collided in mid-air off the coast of Long Beach, Ewell says, “the boat was used for two weeks straight to recover parts of the planes, and to find the victims and return the remains to their families.”

The second boat, if authorized next week by the Board of Supervisors, would similarly do double duty, Ewell says. Like Ocean Rescue II, it is expected to be equipped with advanced life support equipment, and to be set up for large-scale diver operations.

“We’ll use it on medical emergencies, criminal investigations, plane crashes,” he says. “The way budgets are these days, you have to get a lot of bang from the buck.”

Posted 1/10/12

Jail cameras now rolling, sheriff says

November 1, 2011

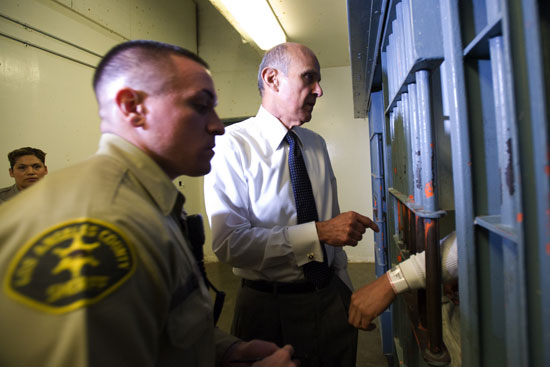

Los Angeles County Sheriff Lee Baca, responding to mounting public criticism and an increasingly impatient Board of Supervisors, said Tuesday that the long-overdue installation of surveillance cameras in the Men’s Central Jail is finally underway and that new measures have been mandated to ensure faster investigations of alleged brutality by deputies.

“My intent …is to reduce force to the absolute barest minimum,” Baca told the supervisors as he presented a report on the department’s progress in implementing an array of reform recommendations, from banning flashlights as “impact” weapons to nabbing violent deputies through undercover sting operations. Baca said some use of force in the jails is inevitable but that he wanted to manage such situations “so that we are not the provocateurs of force.”

The flurry of action inside the department comes at a time when an independent investigative commission, created recently by the Board of Supervisors, has started to take shape. As of Tuesday, three of the five supervisors had announced their selections to the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence, all of the nominees well known figures in judicial and criminal justice circles.

They are: Lourdes G. Baird, a former U.S. attorney and retired federal judge, selected by Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky; retired U.S. District Judge Dickran Tevrizian, named by Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich, and Carlos R. Moreno, a former associate justice of the California Supreme Court, who was picked by Supervisor Gloria Molina. [Updated 11/3/11: Supervisor Don Knabe announced Thursday that he has selected Long Beach Police Chief Jim McDonnell, a former LAPD Medal of Valor recipient, as his nominee to the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence.]

Baca, confronting the biggest controversy of his four terms as the county’s elected sheriff, has said he supports the commission’s scrutiny. Long considered one of the nation’s most forward-thinking law enforcement officials, Baca suddenly finds himself at the center of a storm over the alleged mistreatment of inmates under his department’s supervision. The ACLU, which monitors alleged brutality within the county’s bursting jail system, has called for the sheriff’s resignation.

In a stunning public concession several weeks ago, Baca told the Los Angeles Times that his command staff had not kept him fully informed about problems within the lockup, thus slowing the implementation of reforms to curb excessive force.

“I wasn’t ignoring the jails,” Baca said, “I just didn’t know. People can say, ‘What the hell kind of leader is that?’ The truth is I should’ve known. So now I do.”

Specifically, Baca said that during a recent visit to the Men’s Central Jail, he spotted 69 video cameras still sitting in boxes in the captain’s office. They’d been purchased more than a year ago, at a cost of $157,530, to monitor inmates and deputies.

In his testimony Tuesday, Baca said that all those cameras are now up and running, along with 17 others that have been installed in the booking area of the Twin Towers jail. An additional 300 cameras were ordered last week, at a cost of $308,306, and will be installed within five months, Baca told the board members.

“The need for them was yesterday, not five months from today,” Supervisor Antonovich responded.

“This is like the third time we’ve asked for these cameras to be installed,” Molina said.

Baca explained that the high cost of installation quoted by an outside company had slowed the timetable. Now, the work is being done in-house.

Despite skeptical questioning, Baca also assured supervisors that he has put in place new policies to review cases involving severe use of force in the jails within 30 days—one of a series of reforms recommended over the years by two Sheriff’s Department watchdogs, Special Counsel Merrick Bobb and the Office of Independent Review. Both report to the Board of Supervisors.

Currently, such cases “just sit around for a long time,” Molina said. Baca insisted that his new Custody Force Response Team will be able to meet the new 30-day deadline.

“I’m confident that when we talk about this in two more months, I’ll have some data for you,” Baca said.

According to the sheriff’s report, another potential reform being considered is whether jail deputies should wear video cameras while interacting with inmates. The report said the department currently is looking at three different camera models to see how they might work in county jails.

Another longstanding reform recommendation—creation of a “two-track career path” for deputies inside and out of the jails—also remains under review. Critics have long complained that the current policy of assigning all new deputies to years of service in the jails before they’re placed on patrol duty can contribute to hostility and brutality toward inmates. The department is now working with the deputies’ union on a way to offer alternatives, said Baca’s report, which begins with this “mission” statement:

“Until all deputies feel a sense of professional accomplishment while providing sensible and constitutionally established services to those in our care, our success as a department is not accomplished.”

Posted 11/1/11

Cracking down on jail beatings

October 26, 2011

A united Board of Supervisors sent a strong message to the Sheriff’s Department this week that it will not tolerate brutality in the county’s jails, insisting that such conduct by deputies not only undermines the constitutional rights of inmates but also shatters public confidence in the wider law enforcement community.

A united Board of Supervisors sent a strong message to the Sheriff’s Department this week that it will not tolerate brutality in the county’s jails, insisting that such conduct by deputies not only undermines the constitutional rights of inmates but also shatters public confidence in the wider law enforcement community.

During its Tuesday meeting, the board approved a series of get-tough recommendations that call for, among other things, the installation of surveillance cameras throughout the sprawling jail system, a ban on using heavy flashlights as weapons, a mandate for medical personnel to report “suspicious” inmate injuries and a requirement for more intensive supervision.

But perhaps most ambitiously, the board created a seven-member commission to examine excessive force in the nation’s largest jail operation and provide a road map for reform.

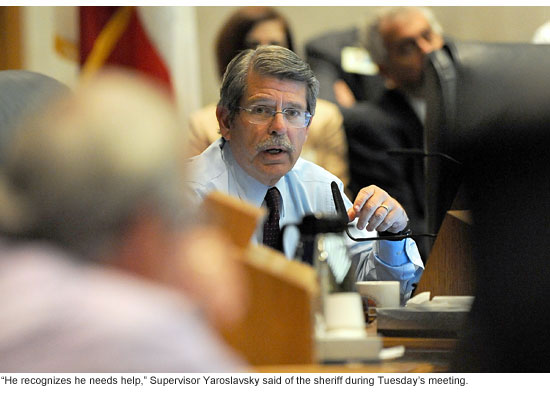

“There are jails around the country that have had problems like ours in the past and they’ve turned themselves around,” said Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, who, with board colleague Mark Ridley-Thomas, called for the commission’s creation. “We’ve got to do that here.”

Yaroslavsky said the job involves more than promulgating new policies or rules. The commission’s most crucial and daunting role, he said, will be to determine the “fundamental issue” of how a small minority of abusive jail deputies have succeeded in “contaminating the entire culture of the institution.”

Yaroslavsky said Sheriff Lee Baca, who did not attend Tuesday’s session, supports the new Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence, whose work is certain to be closely scrutinized by inmate advocates and civil liberties groups that have long complained about—and litigated over—conditions in the county’s overcrowded lockup.

“I think he needs help,” Yaroslavsky said of the sheriff. “And he recognizes he needs help. And I think we [the supervisors] need help. There is no monopoly of wisdom or information on the board, at the Sheriff’s Department or any other place.”

In pushing for “a fresh set of eyes” to examine inmate mistreatment, Ridley-Thomas said the Sheriff’s Department cannot be asked alone to tackle unwarranted deputy violence, which has persisted despite earlier and ongoing probes.

“There is a level of insularity that will only lead to our being back here over and over again,” he predicted. “To leave it exclusively under the domain of the Sheriff’s Department is problematic.”

Each of the five supervisors will appoint one member to the new commission, which will then name two more. The Board of Supervisors has asked staff for a budget plan for the commission, with funding coming from a Sheriff’s Department account used to pay lawsuits and settlements. It’s hoped that at least some of the commission’s staff will perform the work on a “pro bono” basis.

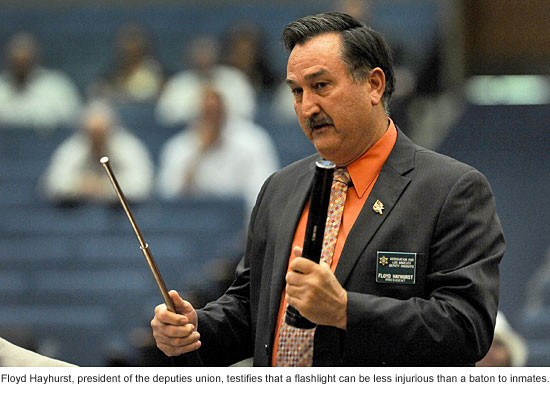

Before the board unanimously voted to create the commission and adopt nearly a dozen recommendations in a motion by Supervisor Gloria Molina, the deputies’ union chief urged supervisors to remain open-minded.

“I’m not here to claim that we have never had, nor will ever have, any bad personnel,” said Deputy Floyd Hayhurst, a 29-year-veteran of the department and president of the Association for Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs, or ALADS. “We do, just like all of the professions. However, I’m here to ask you not to paint all of us with a broad brush and think we are not performing our jobs to the best of our ability with honor, dignity and respect.”

Despite years of controversy, the issue of excessive force in the jails has gained momentum in recent weeks with reports by the ACLU and in the Los Angeles Times of cases in which deputies allegedly brutalized inmates in front of civilian monitors and others who were shocked and scared by the behavior. There were also revelations of an FBI investigation into alleged jailhouse beatings.

Meanwhile, the Office of Independent Review, which monitors the Sheriff’s Department and reports to the Board of Supervisors, released a study earlier this month that turned up the public heat.

Describing the jail as a “cauldron of inmates, many with violent criminal histories,” the report said “it cannot be denied that deputies sometimes use unnecessary force against inmates in the jails, either to exact punishment or to retaliate for something the inmate is perceived to have done.” The OIR study further stated say that some deputies “get away” with these beatings because they “can craft a story of justification for the force which may be impossible to disprove.”

Among the questions the board has asked the Sheriff’s Department to explore in the weeks ahead is one that has been debated for at least two decades. That is: should the department continue its policy of requiring all new hires to start their careers in the custody division, where they can serve for years before assuming patrol duties?

Critics contend that impressionable rookies become quickly hardened by spending years in a grim environment among violent and hostile criminals. Not only do some deputies become brutal jailers, according to the critics, they end up carrying these aggressive behaviors and poisoned perceptions with them when they eventually hit the streets.

On the other side, top sheriff’s officials have long argued that custody experience prepares deputies—many of them young and naïve—in learning how to deal with gang members and other criminals as well as how to assert control without the use of a gun.

Currently, according to the department, the 3,500 deputies assigned to the jail spend an average of 3 to 5 years there. The board wants to know whether that time can be reduced and whether it’s advisable to create two separate career paths for deputies—one for custody duties, the other for patrol—an idea to which Baca has said he might be open.

Ultimately, it’s the sheriff who’ll decide what changes will be made in a department that L.A. County voters have elected him to lead. But as Supervisor Molina noted: “We do have a little bit of leverage because he has to get his budget approved by us.”

Posted 10/20/11

Deadly force by deputies targeted [updated]

September 26, 2011

A study released Thursday takes aim at shootings by deputies in the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, concluding that Latinos and blacks are shot in disproportionately higher numbers when compared to their arrest rates and that an unusually large number of unarmed individuals were fired upon last year.

In his 30th semi-annual report to the Board of Supervisors, Special Counsel Merrick Bobb also expressed “deep concerns” about the consistently high numbers of shootings in the department’s Century Station, where a large percentage of deputies have been involved in multiple shootings and where many, he says, have fallen behind in the department’s mandated training.

Moreover, Bobb was sharply critical of the department’s record-keeping. He disclosed that data on shootings is “missing, inaccurate, lost, or lacking in basic internal integrity.” This, he said, undermines the department’s ability to thoroughly track and analyze the use of deadly force, an issue that carries with it powerful community emotions and potent financial risks for the county.

Sheriff Lee Baca had no immediate comment. But department executives, who were shown a copy of Bobb’s report last week, questioned some of its methodologies, assumptions and conclusions—especially those involving race. In some cases, they say, the report relies on dated information from the 2000 U.S. Census. They also expressed concerns that reporters might take some of the report’s sharply worded statements out of context.

As a result, Bobb agreed to include with his report a five-page “transmittal letter” addressed to Baca. In it, Bobb reiterates his findings but stresses that he is not contending that any shootings were racially motivated.

“Your staff has expressed concern that the media might misinterpret this report because of its frank discussion of the race and ethnicity of persons shot by the LASD,” Bobb wrote. “It would be a serious error for anyone to conclude from this report that LASD deputies intentionally shot any individual because that individual was black or Latino.”

He added: “The LASD’s beef should be directed more at the media than at the messenger.”

Bobb’s report examines hit-and-miss shootings between 1996 and 2010, a 15-year span during which 178 persons were killed by sheriff personnel and 204 were wounded. For the most part, however, he focuses on the past six years.

Although the numbers cited in the report are not large enough for formal statistical conclusions, Bobb and his staff reached their findings on racial breakdowns by, among other things, comparing shootings with overall arrest rates. By this measure, the report argues, Latinos are “overrepresented,” meaning that they are fired upon more often than other races when compared to their arrest rates. White individuals, the report says, are “underrepresented.”

“This disproportion is particularly stark,” Bobb writes, “in the year 2007, when a full 72 percent of all shootings Department-wide involved Latinos. Shootings of African Americans by LASD personnel appeared more proportionate to the overall arrest rate than that of other groups.”

The report also breaks down the race of the deputies involved in the shootings; 47 percent were Latino, 42 percent were white, 7 percent were black and 2 percent were Asian American or Filipino.

Bobb says one of the study’s most troubling findings involved a spike last year in so-called “state of mind” or “perception” shootings, those in which a deputy believes, accurately or not, that a suspect is armed or is reaching for a weapon. In 2010, these increased by 50 percent, from 9 to 15, according to the report. Of these, 8 suspects were wounded.

None of these 15 individuals were later confirmed to be carrying a firearm, though some may have had time to dispose of one before their apprehension. In these “state of mind” shootings, Latinos and blacks also were disproportionately represented, according to Bobb.

“It goes without saying that such incidents, particularly where the victim turns out to be unarmed, carry the potential for great tragedy,” the report states. “They also present a risk of significant liability to the County and may make the work of LASD deputies more difficult by fomenting distrust among the population they serve.”

Bobb’s report calls on the department to reevaluate and improve its training, while doing a better job of collecting data to track and reduce such shootings.

Bobb also urged the sheriff’s officials to scrutinize the reasons behind the Century Station’s consistently high number of shootings—nearly double the number at the department’s next busiest station, Lennox. Century is based in Lynwood and includes some of the region’s most active gang neighborhoods, including the Florence-Firestone area.

Although it would be expected that a station like Century would have more shootings, Bobb says the number has remained high even as homicide and violent crime rates have fallen, a trend that he argues should lead to fewer cases of deadly force.

He said that 56 percent of all shootings at Century, involved a deputy who’d been involved in an earlier incident. Deputies there also had “relatively poor results” in attending annual or bi-annual refresher “shoot/don’t shoot” training. (Deputies do, however, engage in other shooting scenarios at the practice range.)

“We urge the department,” the report says, “to focus intensely on Century and its performance in this area.”

Posted 9/22/11

Updated 9/22, 6 p.m.:

Late today, Sheriff’s Department officials released a 26-page response to the Bobb report, mostly reiterating earlier complaints they had voiced with the special counsel.

Specifically, the department challenged Bobb’s “flawed analysis” in which he used comparative arrest statistics to conclude that Latinos and blacks were more likely to be the targets of lethal force than other races. The department said that Bobb used countywide arrest statistics, not those that would specifically account for the kind of violence and weapons deputies confront daily in gang-plagued areas.

The department also criticized Bobb for relying on outdated, 2000 Census information. During the past 10 years, according to the department’s response, the Latino population within the sheriff’s territory has increased 21%, further skewing Bobb’s analysis.

As for “state of mind” shootings, the department acknowledged that, in 2010, deputies fired at 15 unarmed people, hitting 8 of them. But the department said that “all of them involve suspects who were engaging in activity that was criminal in nature, non-compliant or both.”

Department officials also took issue with Bobb’s contention that many deputies were not complying with departmental training mandates that would help them determine when—and when not—to shoot. They said this training could be fulfilled through various courses, not just the one identified by the special counsel.

The department did agree that elements of its data collection could and will be improved.

To read the sheriff’s complete response, click here.

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink