Spotlight Story

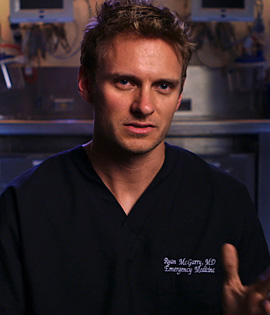

Cracking the ER “Code”

August 13, 2014

In the beginning, the idea was simply to produce some archival footage—a project pitched by a young medical student to document life-saving efforts unfolding amid the controlled chaos of the emergency room at Los Angeles County’s old General Hospital.

It was there, on the edge of downtown, that the concept of emergency medicine was born in 1971 and, in some respects, had remained the same in theory and practice throughout the ensuing decades.

Despite medical modernizations that had become the norm at most hospitals, the emergency crew at the renamed Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center still operated more like a battlefield MASH unit. Crowds of doctors and nurses swirled around patients suffering the most catastrophic of injuries. Side by bloody side, the stricken were packed into a cramped trauma bay in the ER called “C-booth,” with barely a curtain between them.

But in 2008, all that was about to change, and first-year resident Ryan McGarry, who also had a keen interest in filmmaking, wanted to capture the era before it was gone. Because of earthquake damage to the old county hospital, the emergency department was moving next door to a new state-of-the-art facility that would rocket the doctors into 21st century medicine, complete with its emphasis on patient privacy and layers of paperwork.

Although initially modest in scope, McGarry’s ambitions for the project soared with the support of top Los Angeles County officials and the help of a producing team that included USC Distinguished Professor Mark Jonathan Harris, who has won three Academy Awards for documentaries.

McGarry’s film, Code Black, opened nationwide in June and has become a critical success, a gripping and graphic look at the shifting world of emergency medicine for the destitute and working poor who rely on public hospitals, such as County-USC, for their care. The term Code Black refers to the hospital’s designation for the highest level of emergency room crowding. Among other honors, the film won the Jury Award for best documentary at the 2013 Los Angeles Film Festival.

Focusing on a cadre of idealistic young residents, including himself, McGarry explores the challenging new realities for the next generation of emergency room physicians as they remain committed to maintaining a personal connection with patients while confronting the escalating regulatory demands and settings that emphasize patient privacy.

Dr. Sean Henderson, chairman of the hospital’s emergency department, says his 21-year-old daughter saw the documentary at a film festival in Santa Barbara and was so inspired that she changed her major.

“She decided to become a physician’s assistant because of that movie,” he said.

“Often, doctors are portrayed as overpaid snobs who don’t really care,” he continued the other day, sipping a caffeine-free Coke in his office in the old county hospital. “But I think you’ll see in this movie that this is not always the case. There are people doing things because they really care about the people they serve.”

Still, Henderson said he has some personal reservations about the film—a project he inherited from his predecessor, Edward Newton—and isn’t sure he would have green-lighted it himself.

“I’ve never believed in cameras in the hospital,” he explained. “The fact that you’re in an emergency room with an unplanned, unscheduled, unanticipated event—stressed, waiting, probably less informed than you’d like to be—I think that’s a very vulnerable place to be.”

That said, Henderson praised the filmmaker for getting two sets of consents from patients whose emergency room visits are shown in the film—everyone from a drunken man belting out a romantic ballad in the waiting room to the family of a patient whom doctors unsuccessfully fought to save as they cut into his chest to keep his heart beating.

Henderson, who became department chair in 2012, also appears in the film, but mostly to defend a prominently featured action he imposed in the face of a severe nursing shortage. In a dramatic segment of the documentary, he shut down an area of the new emergency department, creating a monumental patient backlog, to make the point “that we couldn’t continue to care for all these people with inadequate resources.”

“I caused the crisis and I had to defend the crisis. I was the villain,” he said, and then offered a fuller explanation of his actions than he did in the film.

He said that in the past, before Health Services Director Mitchell Katz’s arrival in 2011, “the way you got attention in the county system was to create a crisis. It wasn’t just me. It was throughout the system…If you have a crisis, resources are pulled from someone who’s not having a crisis to take care of your crisis. And so, without permission from the school [USC] or the county, I created a crisis knowing full well that it would create a pushback downtown that would allow them to hear my pleas that heretofore had gone ignored.

“It was manipulative, it was sneaky, and mea maxima culpa. But it worked,” he said, noting that more funding was soon made available for the desperately needed nurses.

Another top L.A. County emergency department official, Dr. Erin Wilkes, said she’s seen her good friend McGarry’s film more than a dozen times in various stages along the way. The two were residents together, beginning in the old hospital’s emergency department. Today, she’s the director of Emergency Medicine Systems Innovation & Quality.

Wilkes said she helped organize various Code Black screenings for county officials, including the Health Services executive team. The feedback was mostly positive, she said, although “there were a lot of questions about what the consent process was like.” Wilkes said McGarry obtained his first consents at the hospital and then got a second round of permissions after showing people the actual footage he wanted to use.

Wilkes said she’d now like to build on Code Black’s positive buzz by holding a panel discussion event at USC that would include McGarry, now an assistant professor of emergency medicine at New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical College.

In a recent interview with the emergency medicine publication ACEPNow, McGarry talked about the demands of simultaneously pursuing his residency and filmmaking. “It was three years of no vacation,” he said. But he said he had no regrets.

“One thing that I feel very lucky to have experienced,” he said, “is nonmedical people sitting through some pretty tough stuff in cases we show. And at the end of the film people give us a standing ovation. I wish I could share that with every physician, nurse and X-ray tech who leaves a really tough shift.”

Posted 7/17/14

A park vote to keep the green flowing

August 6, 2014

From the Malibu Pier to trails running through the Santa Monica Mountains, from a dog park in La Crescenta to a skate park in Downey, two L.A. County park measures have generated nearly $1 billion in improvements over the past two decades for some of the region’s best-loved gathering places, great and small.

The measures—Proposition A in 1992 and a follow-up initiative known as “Baby A” in 1996—have helped to fund 1,545 projects across the county including “tot lots,” tree planting, swimming pools, soccer fields, bikeways and fitness gardens, along with facilities for seniors and youth, wildlife habitat projects and graffiti abatement services.

Among the measures’ most broadly visible success stories: a new shell installed at the Hollywood Bowl, a county park, in 2004; the extensive restoration of the Griffith Observatory, which reopened to the public in 2006; and expansion of the Kenneth Hahn State Recreation Area, with amenities including a play area and ball fields. Prop. A funding also has helped transform El Cariso Community Regional Park in Sylmar, which now boasts new features including soccer fields and a 15,000-square-foot community center and gymnasium. And it is allowing kids to make a splash this summer in the new Olympic-sized pool at Belvedere Park in East Los Angeles.

But the flow of green amenities to parks in L.A. County’s unincorporated areas and its 88 cities could be coming to an end, with Prop. A set to expire next June 30. (Its 1996 counterpart will finish in 2019.)

Concerned about derailing a successful program of investing in local parks and recreation facilities, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors decided this week to place on the November ballot a measure that would essentially carry on the 1992 Prop. A for 30 more years, generating a similar $53 million per year.

“We need to do this if we want to keep the momentum going,” said Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, who along with Supervisors Don Knabe and Gloria Molina voted to place the measure on the Nov. 4 ballot. “The public has benefitted from this. They like the parks that have been built. They like the recreational opportunities that have been provided. I don’t think they want to see this come to a grinding halt on June 30 of this coming year.”

But Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich, who joined Mark Ridley-Thomas in opposing the action, said it was too soon to place what he called a “half-baked tax” before the voters, especially since Prop. A ’96 is continuing for several more years and some unspent funds remain in Prop. A coffers.

Russ Guiney, the county’s director of Parks and Recreation, acknowledged that there is a current balance of $154 million in Prop. A funds, but said $20 million of that is committed to upcoming projects. Unless the proposed continuation of Prop. A passes, the remaining funds will be spent down rapidly on park projects and maintenance demands that run around $55 million annually, Guiney said.

The average homeowner currently is assessed $13 a year for Prop. A ’92 and $7 annually for Prop A. ’96, for a total of $20 a year. The measure now heading to the Nov. 4 ballot would replace the Prop. A ’92 assessment with a flat tax of $23 a year per parcel. If passed by the required two-thirds of county voters, that would bring the average homeowner’s total tab for park improvements to $30 per year.

Guiney noted that 64% of voters approved the 1992 measure, and even more—65%—voted in favor of the 1996 proposition.That bodes well, he said, especially since so many projects built with funds from the previous parks measures are now visible and being used enthusiastically by the public.

“I think the voters understand and appreciate this, based on past history,” he said. “We’re optimistic.”

Posted 8/6/14

Sky rangers get their day in the sun

July 24, 2014

Not many people immediately think of the Santa Monica Mountains as a hotspot for star sightings in L.A. But Ranger Robert Cromwell of the National Park Service has a contrarian view when it comes to glimpsing famous luminaries.

“Meteor showers, the Orion Nebula, Saturn, Jupiter, the Transit of Venus, which only happens once every 110 years—we’ve had some spectacular sightings up here,” says Cromwell, the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area’s coordinator of night sky programs.

“It’s always eye-opening to people,” he says. “Here we are, right next to one of the world’s biggest cities and yet you can actually see the Milky Way.”

This, Cromwell says, is partly because preservation of the night sky has become a priority in the mountains, both by the National Park Service and by the county, which has regulated artificial light in rural areas with a Dark Sky Ordinance since 2012. Soon, a sweeping new environmental plan for the Santa Monica Mountains, awaiting final approval by the Board of Supervisors, will protect those starry night views for generations to come.

Cromwell and a small team of park volunteers and rangers have made it their business during the past three years to turn the public on to Los Angeles’ celestial treasures and to the importance of protecting night skies from light pollution.

Cromwell calls his team “The Night Sky Rangers.” Since 2011, when they threw their first mountaintop stargazing party, astronomy events at the recreation area have become seasonal extravaganzas. Last year’s Summer Star Festival drew a crowd of 800, and this year’s, scheduled for August 2 at 7:30 p.m. at the park’s Paramount Ranch, is expected to be just as popular, if not more.

More than a dozen telescopes will be trained to night sky attractions, the Santa Monica Mountains Ranger Band will play astronomy-themed rock music, and there will be children’s programs and lectures by local astronomy and physics professors.

The emphasis on night sky preservation stems from a National Park Service decision in the late 1990s to formally recognize the night sky as a natural resource. As development encroaches on wilderness across the nation, streetlights and billboards have systematically crowded out starlight. Two-thirds of Americans, by some estimates, are now unable to see the Milky Way from their backyards.

Natural nighttime darkness is important not only to the circadian rhythms of humans but also to many wildlife species, who rely on natural patterns of light and dark for navigation and protection from predators.

Some national parks are renowned for their lack of light pollution. Death Valley National Park, for instance, is home to an assortment of Full Moon Festivals and Mars Fests, and the International Dark Sky Association has designated it the world’s largest “dark sky” park.

Most of the Santa Monica Mountains recreation area, which straddles the Los Angeles-Ventura County line north and west of the city, is too close to L.A. and saturated by city lights to get that kind of a designation, says Cromwell.

“But there are some sites within the mountains that I think have potential,” he says.

The Dark Skies Ordinance, passed two years ago by the county, restricts rural lighting across a designated district that hopscotches from Rowland Hills through the Antelope Valley and the Santa Monica Mountains to the coast. County code enforcement officers say that since the ordinance’s passage, cases have dropped to a handful as rural property owners have become better educated on the issue.

Park officials also have played a role in raising consciousness. Among other things, they’ve weighed in on development proposals, working with the City of Agoura Hills, for instance, to prevent light from a parking lot from encroaching too badly on a nearby wildlife corridor.

The park also has dimmed its own light footprint, hoping to lead by example.

Park spokeswoman Kate Kuykendall says about 65 percent of the park’s lighting is now night-sky-friendly LED, and outdoor fixtures are being switched to point downward instead of toward the sky.

Cromwell, who has been a ranger in the Santa Monica Mountains for five years, says the night sky has fascinated him since his childhood in Moorpark. One of his most vivid memories is when he was about 11 or 12 and surfing Malibu at twilight. He laid back on his board.

“It was one of those clear nights that you don’t always get at the beach, and I remember looking up and seeing the stars and seeing them reflect on the water,” he says of that memorable summer evening. “I was just, like, wow.”

The astronomy festivals grew out of a 2010 Yosemite National Park workshop. The national parks were encouraging night sky programming, Cromwell says, and although astronomy so close to a city seemed a challenge, he and his fellow park workers decided to try.

He, volunteer campground host Tony Valois and Ken Low, another park ranger with expertise in the night sky, have developed relationships with local enthusiasts, who now provide help and equipment. At the upcoming festival, for example, the Ventura County Astronomical Society will provide some of the telescopes, Cal Lutheran University Professor Mike Shaw will offer a family friendly tutorial on stargazing and Hal Jandorf, an astronomy professor at Moorpark College, will lead a constellation tour.

“The experts really make it possible,” Cromwell says. “And when people look out and see the glow from a development or something, they become conscious of how important it is to preserve experiences like this. Because on clear nights, you can see other galaxies sometimes. It’s spectacular.”

This year’s Summer Star Festival is scheduled for August 2 from 7:30 p.m. to 10:30 p.m. at Paramount Ranch, 2903 Cornell Road, Agoura Hills. In the event of rain, the program will be cancelled. For more information, call 805-370-2301

Last summer's festival drew a crowd of 800. Red cellophane light filters are used to reduce glare. Photo/Mike Shaw

Posted 7/24/14

Bursting in air o’er Grand Park

July 2, 2014

There was a time when fireworks on the roof of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion would have been as hard to imagine as a crown of sparklers on the head of its namesake philanthropist/socialite.

The Dorothy Chandler was the stateliest spot in one of the stateliest cultural centers in the country, surrounded by high rises and imposing government buildings. And downtown was a place that many Angelenos went for work, if they went there at all—not a prime destination for frolicking in a park.

Talk about changing times.

Last year, some 10,000 showed up at Grand Park for its first Fourth of July party, so many that organizers thought it was a fluke until 20,000 arrived for New Year’s Eve.

Now, armed with lessons learned since the park opened in 2012 as an instant L.A. icon, park officials are replacing old rules with a growing playbook of downtown event planning. On the horizon: Everything from more ambitious community gatherings to a two-day Budweiser Made in America event on Labor Day weekend, featuring John Mayer, Steve Aoki and, possibly, Jay Z (park officials say he hasn’t confirmed yet).

This Fourth of July, Grand Park programmers are anticipating some 25,000 people, and are preparing a downtown perimeter to potentially handle twice that many. Two live bands—one soul, one indie—will provide music, twice the entertainment provided last year. No alcohol will be allowed in the park (bags will be checked.) But there will be more food trucks, more security and, thankfully, more bathrooms. Organizers have even lined up a free bike valet to help park your ride.

Most striking, though, will be the changes in the pyrotechnics.

“Last year, we shot off the fireworks in the middle of the park, which meant we forfeited some of the real estate that people could have used to gather,” says Julia Diamond, Grand Park’s programming director.

This time, she says, the fireworks will come from the roof of the Dorothy Chandler, where programmers turned in an effort to save space and maximize visibility for the park’s farflung neighbors.

“We’re recognizing that these park events aren’t just park events, they’re becoming L.A. events,” Diamond says. “This year, the show will be visible from Boyle Heights, parts of Echo Park, Elysian Park—all over. People will not only have the option to come to the park, but they’ll also be able to watch from home if they want and still have a celebration. And this will give us flexibility to shoot off more and bigger fireworks than we’ve done before.”

The move reflects no small measure of ambition. Last year’s Fourth of July spectacle was impressive, but because the fireworks were launched from ground level, they were more like the stage pyrotechnics at a rock concert than the traditional Independence Day overhead extravaganza.

According to Los Angeles City Fire Inspector Ben Flores, the fire marshal for the Grand Park celebration, the traditional type of show is possible only with the use of projectiles that explode hundreds of feet in the air and require hundreds of feet of clearance so that onlookers aren’t singed by the burning, pressed-wood shells that fall in the wake of the starburst.

Past attempts at urban projectile-style fireworks downtown have had mixed results.

In 2006, for instance, a fireworks display at a black tie gala ignited a small blaze when one of the projectiles accidently flew into a ninth floor window at Los Angeles City Hall.

“Luckily, a sprinkler head was right there,” recalls Flores. “It didn’t so much burn as set off the sprinklers and cause water damage.”

Nonetheless, Diamond says, the experience was sobering enough for city firefighters that no one at the park even suggested City Hall as a staging area for this year’s fireworks.

Because Grand Park is technically part of the Music Center, the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion loomed as the obvious venue.

“We installed new security railings to ensure the production team will be safe,” Diamond says. “And we’ll be using water to hose down part of the Music Center Plaza to make doubly sure there’s no damage.”

The roof itself, she says, is already fireproof. And the location is ideal because the Music Center complex is at the top of Bunker Hill, about 100 feet above the elevation of City Hall.

Diamond says security crews will begin clearing crowds long before the 9 p.m. start time of the fireworks show to ensure that the area around the Music Center is safe and clear for viewing.

And the fireworks’ change of venue should provide plenty of Instagram-ready moments.

“The Department of Water and Power will be right there, which is also an iconic backdrop,” says Diamond. “It’s going to be beautiful.”

Grand Park’s 4th of July Block Party will be held from 4-9 p.m. at 200 N. Grand Ave. in Downtown Los Angeles. The event perimeter will extend from Temple to Second Streets between N. Grand Avenue and N. Spring Street. Doors open at 1 p.m. Music starts at 4 p.m. Fireworks are at 9 p.m.

Posted 7/2/14

The L.A. River’s stormy past

June 5, 2014

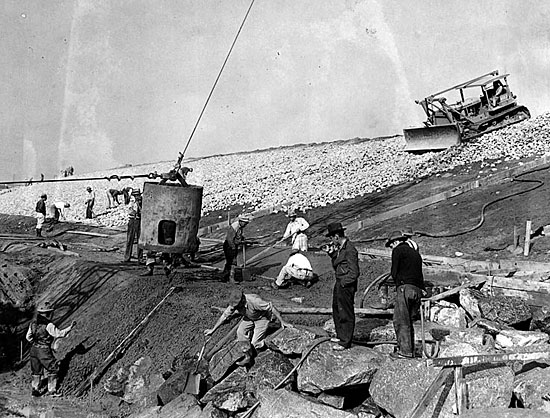

After pounding storms in 1938 brought death and destruction, the river would be tamed with concrete.

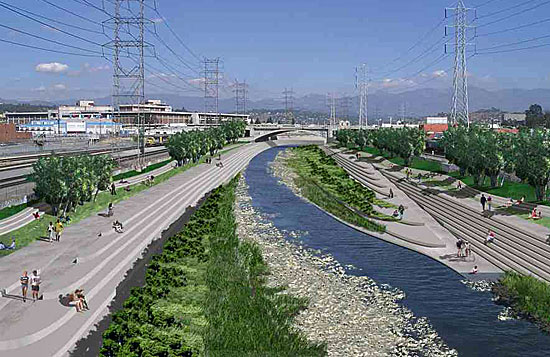

For decades, the Los Angeles River has been ridiculed across the country as being as fake as a Botox brow, maligned in its own backyard as nothing more than a 51-mile concrete eyesore. But the river’s image is about to undergo a game-changing makeover, thanks to the Army Corps of Engineers’ recent endorsement of a $1 billion revitalization plan, which more than doubled an earlier recommendation.

The plan to transform an 11-mile stretch of the river from Griffith Park to downtown L.A. is intended to give people of all ages a healthy urban getaway, where they can relax and play. But back in the days when the river was first encased in concrete in one of the nation’s largest Depression-era public works projects, the federal government’s investment was about much more than improving lives. It was about saving them.

The unpredictable waterway had killed hundreds of people during a series of storms that had repeatedly devastated the region over the previous half-century. Two particularly vicious wallops in the 1930s forced local officials to seek federal help. The first, in 1934, killed dozens of people in a watery siege witnessed by folk songwriter and poet Woody Guthrie, who memorialized it in The Los Angeles New Year’s Flood:

Whilst we all celebrated

That happy New Year’s Eve,

We knew not in the morning

This whole wide world would grieve;

The waters filled our canyons

And down our mountains rolled;

That sad news rocked our nation

As of this flood it told.

No, you could not see it coming

Till through our town it rolled;

One hundred souls were taken

In that fatal New Year’s flood.

But it was the urgency generated by a second deadly storm, this one in 1938, which brought the biggest infusion of federal dollars through the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration to protect the safety of one of America’s fastest growing regions. Between February 27 and March 3 of that year, Los Angeles, Orange and Riverside counties were drenched by more than 10 inches of rain. The river jumped its banks and flooded a third of the city, killing 115 people, while destroying or damaging more than 6,000 homes. Total property damage was about $1.44 billion in today’s dollars. (See video footage of the flood here.)

The Los Angeles County Flood Control District, overseen by the Army Corps of Engineers, put 17,000 people to work on the job at the height of the Great Depression. Almost all of the work was done by hand. They moved 20 million cubic yards of earth, poured 2 million cubic yards of concrete, laid 150 million pounds of steel and set 460,000 tons of stone. The entire length of the L.A. River was channelized, along with 147 miles of tributary channeling. Also built were 5 flood control basins and 316 bridges.

The transformation of the river took 20 years to complete.

By the time it was finished, the L.A. River was unrecognizable from its natural state. About 90% of it had been lined with concrete along its sides and bottom. A natural riverbed was kept for the remaining 10%. Formerly a home for frogs, fish and birds, the river became a graffiti-scarred channel for urban runoff and garbage, sending pollutants of various sorts speeding towards the sea. It was immortalized in movies like Grease and mocked by comedian Conan O’Brien.

It was, in short, a river in name only—a reputation that restoration leaders are now determined to change, while maintaining the river’s ability to control flood waters.

In addition to the billion-dollar revitalization project, there are ongoing efforts to build a continuous 50-mile bike path and greenway along the river. Last summer, a pilot kayaking program was launched in the Elysian Park neighborhood. Based on its success, the L.A. City Council voted in February to make the program permanent, while expanding it to another section of the river, the Sepulveda Basin.

So for now, although the history of the L.A. River is still being written, a new chapter has opened.

Posted 6/5/14

The creature from Topanga Creek

May 28, 2014

Louisiana red swamp crayfish may be a delicacy in the gumbo pot, but these voracious Cajun imports are an unwelcome ingredient in Topanga Creek, where they cloud the water and chow down on native fish, bugs and amphibians.

They’ve been in residence since 2001, when a local resident is said to have dumped a batch of live crayfish into the creek in hopes of cultivating a perennial free bait supply. Since then, there have been intermittent community clean-ups, and those efforts—coupled with winter storms that traditionally have washed many of the crustaceans out to sea—were usually enough to keep the population in check. But a lack of significant rainstorms since March 2011 has spawned a crayfish baby boom.

“We’ve had perfect growing conditions for crayfish. The water is slow-moving. It’s warm. And they have gone berserk,” says Rosi Dagit, a senior conservation biologist with the Resource Conservation District of the Santa Monica Mountains. “They’re a very intense predator…It’s kind of gotten out of control.”

That’s bad news for the health of the creek and also for creatures like the California newt, a snack of choice for hungry crayfish.

“One day we literally witnessed a newt in the hands of five crayfish,” says Lizzy Montgomery, 25, a Watershed Stewards Project intern working at the site. Montgomery and her fellow intern, 24-year-old Crystal Garcia, are in the midst of a crayfish research and removal plan now underway at the creek.

They rescued the newt, but the sight of the near-carnage was enough to help Montgomery get over her qualms about dispatching the crayfish with extreme prejudice. (The creek is clean but the crayfish are bottom-feeders and probably not suitable for people to eat, Dagit says. The collected specimens have been frozen and donated to the Nature of Wildworks wildlife center as food for raccoons being rehabilitated there.)

The interns haven’t been working alone. Starting in October, they mobilized a brigade of local schoolchildren from Calvary Christian School in Pacific Palisades and the Topanga Wildlife Youth Project to conduct weekly crayfish removals in a section of the creek. Their haul to date: more than 400 crayfish.

With the end of the school year, the program has gone on hiatus but Montgomery and Garcia say they hope to bring it back. Supervised removals are important because of Topanga Creek’s delicate eco-system; the creek is home to several endangered or threatened species and fishing is prohibited, with special permission required for any crayfish removal, Dagit emphasizes.

Meanwhile, Montgomery and Garcia also are conducting scientific research comparing the cleaned-up area with an adjacent part of the creek where the crayfish continue to run wild. They’ve already created a scientific poster that they’ve presented at two conferences, and hope eventually to have their findings published by the Southern California Academy of Sciences.

Their internships, funded by a grant from the office of Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, are set to end in August. After that, it will be time for an all-too-common Southern California pastime—hoping for rain. Even a wet winter probably wouldn’t be enough to completely eliminate the crayfish, which Dagit says are now established in most of the creeks in the Santa Monica Mountains. But it would help keep the invaders in check.

“What we’re hoping is that we’ll get some really good rains and that the population will get severely diminished,” Dagit says. “And at that point we will mobilize people as best we can to do a really concerted removal.”

For a peek at how it’s done, check out the YouTube video below.

Posted 5/28/14

County fish story no whopper

May 22, 2014

L.A. County crews hauled tons of anchovies and sardines out of the marina, with help from the pelicans.

You could see in the sky that something was fishy.

On Sunday, hundreds of pelicans were dive-bombing the waters of Marina del Rey, while swarms of screaming gulls circled overhead. “It was like a scene out of Hitchcock,” recalled Kenneth Foreman of the Los Angeles County Department of Beaches and Harbors.

But unlike the film version, these frenzied birds (and legions of gluttonous sea lions) were gorging themselves on a spread of anchovies and sardines—a very big, stinky spread. For reasons still unclear, the tiny fish had found their way into a corner of the marina, where they depleted the oxygen and suffocated.

As division chief of the agency’s facilities and property maintenance section, it was Foreman’s job to get rid of the silvery mess that had boaters and residents crying foul.

By late Sunday afternoon, less than a day after the fish surfaced en masse, Foreman’s crews had removed an estimated 6 tons of them. “Our guys did a great job in a short period of time,” said Foreman, a 30-year veteran of the department. For the record, he said, the fish carcasses weren’t placed in a shallow, sandy grave. They were transported by a disposal company to Victorville, where they’ll be converted into compost “so that some beneficial use can come of this.”

The media frenzy that surrounded the weekend die-off and clean-up offered a rare moment in the sun for Foreman’s operation. Away from the glare, his crew tackles everything from cleaning the county’s 51 beach bathrooms to stringing nets on 292 volleyball courts to alerting authorities to the occasional pre-dawn discovery of dead bodies on the sand—some of them apparent suicides.

“I guess the beach was the last thing they wanted to see,” said Foreman, whose 157 employees are also responsible for 1,169 trees, 8.5 miles of sand berms, 4,700 boat slips and 8,161 beach parking stalls.

Every year, between 50 to 60 million visitors flock to the 61 miles of beaches maintained and operated by Los Angeles County. That’s more than all the national parks combined, according to Foreman’s boss at Beaches and Harbors, Deputy Director John Kelly. He said the maintenance division, which has collected 84,000 tons of trash during the past two decades, prides itself on getting the beaches and their restrooms ready before daybreak, unlike some other jurisdictions.

In the early morning, he said, “Santa Monica [beach] parking lots are strewn with trash. You pass by the county beaches, they’re already clean.”

But Foreman’s crews also tackle many less predictable duties that don’t get public notice or end up on the division’s stat sheet.

Foreman said, for example, that in recent years the department increasingly has been called on to help law enforcement authorities deal with “panga” boats abandoned on the sand by drug dealers or illegal immigrants trying to come ashore. The last incident, he said, occurred near Manhattan Beach and led to the arrest of 20 people allegedly trying to enter the country illegally.

More often, however, the department is dispatched to get rid of old, unseaworthy boats that have broken free of makeshift moorings and ended up shipwrecked on the sand.

Sometimes, the division confronts ocean creatures very different from those tiny specimens it encountered over the weekend. It’s not unusual, Foreman said, for dead sea lions, dolphins or whales to wash up on the county’s beaches, as two did in 2012. “Ideally,” he said, “we try to tow them out to sea so Mother Nature can take care of them.” But if it looks like the tide might push them back to shore, “then we try to bury them in the sand.”

“In this department,” he added, “we’ve seen it all. There’s never an opportunity to get bored. Something new and different is going to occur, guaranteed.”

Posted 5/22/14

Bike boom’s hidden headache

May 15, 2014

There’s good news on the cycling front, with a new report showing L.A. bike use growing by 7.5% and new lanes, paths and “sharrows” buzzing with two-wheeling commuters and recreational cyclists.

But there’s also a less heralded statistic in the 2013 Bike and Ped Count released this week by the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition:

Only 46% of L.A. cyclists wear helmets.

That’s troubling to medical experts like Dr. Mitchell Katz, director of the county’s Department of Health Services and a (helmet-wearing) cyclist in his own right.

“The evidence from a medical point of view is very clear: helmets prevent brain injury, and brain injuries are some of the most devastating events besides the possibility that you might actually die,” Katz said.

Katz said his own experiences on the streets of L.A. corroborate the report’s findings on helmet-wearing.

“I’ve noticed that certainly more than half of the bicyclists do not. I think young people are especially guilty of not wearing helmets,” Katz said.

Those riders are taking a big chance, given that 15- to 19-year-olds were the bicyclists likeliest to land in L.A. County emergency rooms in 2012, with 64.3 per 100,000 people in that population showing up to be treated for bike injuries.

Injuries to Los Angeles County cyclists are steadily increasing, from 2,916 hurt in collisions with vehicles in 2007 to 4,759 injured in 2011, according to state data provided by the county Department of Public Health. Twenty-six bike riders were killed in 2007 and 30 in 2011. Only 14% of those injured and just 20% of those killed were using “safety equipment” at the time of their accidents in 2011.

However, the state injury data did not include a specific breakout for helmet usage within the category of “safety equipment”—something Katz said could be helpful in raising consciousness about the dangers of riding without protective headgear.

“I think there is a misconception, that people think, ‘I’m a great bicycle rider. I don’t need to wear a helmet.’ What they’re not thinking of is it doesn’t have anything to do with what kind of bicycle rider I am. It has to do with whether a car hits me and I fly through the air. You don’t have any control, once you’re flying through the air, of how you land,” Katz said.

Adults aren’t legally required to wear bike helmets in California, but advocacy groups like the Bicycle Coalition officially recommend them. And when elected officials like Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti go out for a spin on Bike to Work day, they’re invariably photographed wearing a helmet.

So why aren’t more L.A. cyclists following their lead?

The answer is complicated—and, within the cycling community, often polarizing.

“It can get pretty heated once you start talking about helmet use because there’s a contingent of bicyclists who are really adamant about wearing helmets and there’s a contingent of bicyclists who are really adamant about not wearing a helmet,” said Colin Bogart, education director for the Bicycle Coalition, who advises his students to don helmets and always wears one himself.

Some people “just don’t think it’s that important…it’s the ‘it’s-not-gonna-happen-to-me’ sort of thing,” Bogart said. Then there are those sometimes called “invisible riders”—day laborers and other workers commuting by bike out of necessity and perhaps unable to afford safety equipment like helmets and lights.

And, particularly among younger riders, “there’s the whole coolness factor, right?” Bogart said. “It’s like, ‘You’re a dork if you wear a helmet.’ ”

Underlying the contentious issue is the feeling—held even by bike advocates who strongly recommend helmet use—that too much focus on headgear diverts attention from a broader mission of pushing for better, safer cycling spaces throughout the city.

“I think ultimately what we’d like to see is a situation in which our built environment is such that people don’t even feel like they need to have a helmet because they feel so safe doing it,” Bogart said. “When you look at photographs of people biking in a lot of these cities in the world where the percentage of cycling is way beyond anything we have here, almost nobody is wearing a helmet. [That’s] because it’s viewed as so everyday and so not hazardous to your safety that people just ride without ‘em. “

Although some, like Dr. Katz, think it would be a good idea to pass laws mandating helmet use for adult bicyclists as well as those 18 and under, Bogart said he believes that could deter would-be riders from joining the growing cycling movement.

“That’s a real concern, that if you make it a requirement, a lot of people are just going to say, OK, forget it,” Bogart said.

The helmet statistic was not highlighted in the bike count’s official news release. But it might dovetail with another finding: that fewer than 20% of L.A. cyclists are female. That suggests there still aren’t enough safe bikeways to attract women, traditionally considered more “risk-averse” riders.

To get more women, children and older people bicycling on city streets, the new report calls for creation of more “protected bikeways,” which carve out dedicated space for cyclists to ride with some separation from automobile traffic.

Because let’s face it: “If you’re riding on the streets as they are right now, you’re pretty risk tolerant,” said Eric Bruins, the coalition’s planning and policy director.

Posted 5/15/14

New beach chief rides the waves

May 8, 2014

Gary Jones’ new job as director of the Los Angeles Department of Beaches and Harbors is a little like going surfing while wearing a tie. It’s an ongoing attempt to marry L.A.’s freewheeling beach culture with business concerns such as permits, parking, environmental impact and—always—budget.

Access to L.A. County’s beaches remains an emotional issue for residents, many of whom treasure days at a local beach among childhood memories, Jones says. The 45-year-old Englishman’s first visit to Southern California took him to Venice’s Muscle Beach. “Venice Beach and the L.A. lifeguards are iconic, in part from Baywatch. Surfing, the beach life, the fire pits —that type of culture is very much transmitted around the world,” Jones says.

Jones’ Marina del Rey office affords a picture-postcard view of blue sky, seagulls and sailboats. Hailing from the English “rowing town” of Bedford, he loves to observe rowing teams from UCLA and Loyola Marymount University take on the chilly early mornings. On his desk are the less enticing realities of the gig: The first proposed increases in fees affecting the public since 2009 are set to come before the Board of Supervisors next week. They include increases in summer parking fees, beach permits for organized recreational classes such as yoga, youth camp expenses and dry storage of trailered boats.

And if past experience is any guide, those kinds of changes—ranging from new meet-up rules to a misunderstood Frisbee policy—can kick up a lot of sand.

“In the dynamics surrounding the county’s operation and ownership of beaches and the coastline, there are some very interesting forces at play,” adds Jones, who served as interim director for eight months before stepping into the permanent post on April 15. “Underpinning it all is that overwhelming sense that this is something the public should have access to. Some people think that access translates to free, or as low cost as possible. Or if I want to join 50 or 100 of my closest friends and train for a triathlon, I can do that.”

Standing out among the currently proposed increases are a new fee for the annual senior parking pass ($25) and substantial hikes for five-day youth camps, some of which have recently been on hiatus. Sailing and surf camp fees would go up sharply (sailing rising from $165 per participant to $375, surf camp from $165 to $300). Jones notes that the department continues to look for ways to cut operating costs so fees may end up being lower than proposed. He adds the department will still give financial assistance to needy participants.

Jones says the department is also looking to expand the county’s popular water taxi service that transports the public to concerts and events at Chace Park, along with other stops including Fisherman’s Village and Mother’s Beach. This summer, the service is slated to begin June 19.

Jones, who moved to the U.S. in 1998, began his Southern California career managing assets for the city of San Diego. He came to Los Angeles County’s beaches and harbors department in 2009. Jones stepped into the interim director position when then-director Santos Kreimann became acting county assessor after the elected assessor, John Noguez, was placed on leave pending a trial on corruption charges.

With the approach of Memorial Day and the traditional opening of summer beach season, Jones says his foremost concerns include the continuing redevelopment of Marina del Rey (money from private development flows into the general fund, he says) and beach maintenance for the summer onslaught (sand grooming, restroom upgrades, parking lot re-surfacing).

Also at the top of the list: A greater social media presence and a more user-friendly website to provide up-to-the-minute information on parking and rates, easily accessible by smart phone or tablet.

Jones adds that some beaches require a delicate balance between humans and wildlife. Visitors don’t always understand the needs of the grunion or the Snowy Plover, or why the “rack line” of seaweed left behind by the tide represents an important ecosystem, not just a source of odor and pesky sand flies. “We have 50 million plus people using our beaches every year —how do you balance that with being a good environmental steward?” muses Jones.

And why did Jones take on this balancing act? “No municipal department has the blend of what this department is responsible for,” Jones asserts.

“I don’t think I could have been satisfied churning out commercial real estate deals or office deals,” he says. “It’s very rewarding when you see a project come together and you see people enjoying it, the impact it has on a community. I think that’s what makes me tick.”

Posted 5/7/14

Check for the latest closure information

Check for the latest closure information