Spotlight Story

Defenders mark a century of L.A. law

January 19, 2014

In this 1963 photo, Public Defender Kathryn McDonald confers with client Gregory Powell (left), who was accused with Jimmy Lee Smith in the "Onion Field" killing of LAPD officer Ian Cambell.

In the early 1880s, an Italian immigrant in San Francisco was charged with trying to collect $500 in insurance by torching his house on Telegraph Hill. The man was innocent but could not afford a decent attorney, and when his trial date rolled around, his lawyer didn’t show.

So the judge, as judges did then, went into the hallway and ordered the first lawyer he saw to represent the defendant. This didn’t bode well, since most court-appointed defense lawyers at the time were not only unpaid but also incompetent.

The lawyer—Clara Shortridge Foltz—was, in fact, just out of law school. But she won the case and used it as Exhibit A in a national push that led to the opening of the nation’s first public defender’s office in 1914 in Los Angeles.

One hundred years later, the Public Defender’s Office of Los Angeles County is marking its centennial anniversary. Some 700 attorneys work there now—more than at any criminal defense firm in the nation—along with hundreds of investigators, paralegals, psychiatric social workers and support staff. Last fiscal year, they defended clients in more than 400,000 felony and misdemeanor cases, not counting the thousands more defendants in juvenile delinquency and mental health courts.

Like Foltz, they occasionally make history. And, like Foltz, they tend not to become particularly famous. (In 2001, when the criminal courthouse downtown was renamed in her honor, the Los Angeles Times noted “a chorus of people saying: ‘Clara Who?’”)

“We usually pick up cases because nobody else is there,” says Alan Simon, a now-retired public defender bureau chief who spent five mostly unsung years representing the Hillside Strangler, Kenneth Bianchi.

“But most of the great names in public defense are not the ones that you see in the headlines. Charlie Gessler was probably one of the best defense lawyers ever. Do you know who he is? Probably not.”

Deputy Public Defenders Bernadette Everman and Dave Meyer at arraignment of "Night Stalker" Richard Ramirez.

Less obscure are some of the names of the clients represented over the years by the department. The Night Stalker had a public defender. So did the Onion Field killers and members of the Manson and Menendez families. Public defenders played a key role in uncovering the Rampart scandal at LAPD in the 1990s, and handled the crush of cases filed in the wake of both the Watts Riots and the L.A. Riots.

Most of the office’s clients, however, are the kinds of people to whom society tends to pay little attention—the impoverished, the downtrodden, the lost, the addicted, the difficult.

“It’s a calling,” says Public Defender Ron Brown, who has spent 33 years in the office, where turnover for reasons other than retirement averages a miniscule 2 percent a year.

“Our clients aren’t always nice people,” Brown says. “But somebody has to defend them, and vigorously defend them, in order for justice to be done. So what we do is about protecting peoples’ constitutional rights, and people who work here find that this is a place where they can do God’s work, as corny as that may sound.”

As integral as the Public Defender’s Office now is to the legal system, it was a radical notion when it began. It arose from decades of lobbying by Foltz, whose long list of accomplishments included being the first female lawyer in California. With fellow suffragettes and Progressive allies, she sought to balance the odds in the late 1800s against impoverished defendants who were often railroaded by ambitious prosecutors and judges, even though they were supposed to be presumed innocent.

At the time, the state prosecuted people suspected of criminal wrongdoing, but didn’t underwrite any of their defense costs. A judge could appoint a lawyer to represent a pauper. But the court-appointed attorney, who was duty-bound to take the assignment, had to work without pay, or pro bono.

As a result, few competent lawyers made themselves available for such work. Instead, judges typically drew from the lowest ranks of the courthouse pecking order, often strolling out into the hallways and grabbing whoever happened to be around.

Foltz was outraged by the situation. A lawyer’s daughter, she had turned to the law to support herself after her husband deserted her and their five children. She had a soft spot for the poor.

She also had a knack for agitation: When she learned that only white males could become lawyers in California, she hounded the governor into signing landmark legislation to abolish the inequality. When she couldn’t’ get into law school, she sued for admission. Now, pressed into action on behalf of poor clients, she believed the time had come for lawyers like her to be able to make a living.

So she began agitating for legal reforms that would guarantee a paid defense and balance the odds against the defendant. According to a definitive biography of Foltz by retired Stanford law professor Barbara Babcock, she spent three decades campaigning in state legislatures and drafting model statutes before a political tide of Progressives and women—who had just gotten the vote here—led to success in California.

By then, Foltz was working as a deputy district attorney in Los Angeles County, another first for a woman, and was an influential political voice, both nationally and here. In November 1912, Los Angeles County voters approved a charter that included the creation of the Office of the Public Defender, and the following year, it was ratified by the state legislature.

After a competitive exam, the Board of Supervisors appointed Walton J. Wood, a Los Angeles deputy city attorney, as the first public defender in the nation. The office opened on Jan. 9, 1914.

Over the years, according to Public Defender Brown, the office’s focus has changed with the societal landscape.

“In the past, we looked exclusively at winning—at getting the guy out and moving on,” he says. “The thought was that we’re lawyers, not social workers. But in fact, a good lawyer really is a kind of social worker. You end up getting involved with everything from housing to mental health needs.”

To that end, the office now works closely with social services in the county, from children’s services to mental health. It also has helped pioneer the use of specialized courts for addicts, veterans, the mentally ill and women, and has become involved in communities with programs like Parks After Dark.

And as it heads into its next century, he says, the department has added to its diversity in ways that would probably please the suffragette who made it happen: More than half of the lawyers—from trial lawyers to managers—are female now.

Clara Shortridge Foltz's groundbreaking activism led to the creation of L.A. County's Public Defender's Office in 1914, the first of its kind in the nation.

Posted 2/21/14

Ringing in a Grand new tradition

December 12, 2013

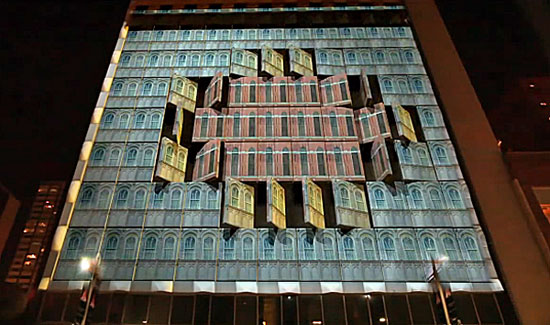

Like the tranformation of this Dallas building, a spectular "3D digital mapping" show is planned for City Hall.

From the first, it was part of the civic vision—a big, free, central place where Los Angeles would, for once, come together in public on New Year’s Eve.

Even while it was on the drawing boards, Grand Park was being touted as a rival to the big, cold-city countdowns that have always seemed to have the market cornered on December 31st at midnight. At meetings, civic leader Eli Broad talked excitedly about the notion, envisioning televised images of a 12-acre party between The Music Center Plaza and L.A. City Hall.

Now, at last, Grand Park will step up with its first New Year’s Eve celebration, an event that, at least for now, may not draw the hundreds of thousands annually estimated at Times Square, but that is expected to set its own kinds of records with a dazzling technological display that will be the largest of its kind ever attempted on the West Coast.

Of course, there’ll be live music, dancing, food trucks and a cash bar. But the highlight is expected to be a colossal presentation of so-called “3D digital mapping”—a high-tech urban art form that will make L.A.’s iconic City Hall do some things that it may have to blame on the champagne in the morning.

“I don’t think anyone in L.A. has done anything on this scale,” says Jonathan Keith, creative director at Idea Giants, the local consortium of 3D special effects artists who created the extravaganza.

The technology, which employs projectors and sophisticated 3D models to make art out of ordinary landscapes, has been used to turn skyscrapers into everything from ancient ruins to giant dancing monkeys. Windows can seem to extrude, walls can seem to fall away, and—in one stunt hinted at by the creators of the New Year’s Eve show—whole landmarks can seem to disappear and be replaced by Grand Park’s renovated jewel, the Arthur J. Will Memorial Fountain. (Click here for a sample of what digital mappers can do to an unsuspecting building.)

Keith says his team will use a 20-foot stack of five 40,000-lumen projectors weighing about 500 pounds each—state-of-the art equipment. “I believe we have every 40K projector in California for this event,” Keith says. “We needed some major fire power with a structure the size of City Hall.”

The party is the most ambitious undertaking yet for park programmers, who have built audiences for the new downtown destination through a number of high profile events. The biggest was on the Fourth of July, when some 10,000 revelers flocked to Grand Park’s lawns to watch fireworks, but thousands also have gathered for events ranging from a live screening of the 2012 Presidential Elections, Mayor Eric Garcetti’s swearing-in celebration, an assortment of outdoor concerts and CicLAvia.

To that end, Julia Diamond, the park’s director of programming, says organizers have tried to err on the side of caution in planning the New Year’s Eve celebration. Although they’re planning for a repeat of the Independence Day attendance, they also avoided bringing too much celebrity wattage to the entertainment lineup, lest a too-massive turnout spoil the park’s vibe.

“I think especially in this early period, the event isn’t about a person or a band, especially on New Year’s Eve,” says Diamond. “Maybe down the road we’ll go with a big national name, but right now, this space isn’t a 100,000-person venue or even a 30,000-person venue.

“We don’t want to re-create the kind of experience you have at Times Square, where you’re smashed into a packed concrete space where you can’t sit down and can’t move and can’t eat. And the bigger names you have, the more you get of those logistical issues. We want people to come in, find a bench, spread out and enjoy themselves with their families.”

A key question, of course, is: What will the countdown look like? Organizers have been close-lipped about the details, but they will confirm that they don’t want their clock to strike midnight the way Times Square’s does either, although there will be a live feed of the ball dropping for early birds at 9 p.m.

“We can represent the passing of time in ways that are much more creative and dynamic and sleek now,” Diamond says. “The ball dropping is great and iconic, but it’s really analog.”

Beyond that, Diamond says, there will mostly be brightness and action. Images of revelers and their hopes for the New Year will be projected on the Hall of Records, as will names of the various communities of Los Angeles County.

“The first thing people will notice is a sort of neon takeover of the park,” she says. “You’ll be surrounded by lights and color and New Year’s Eve.”

The party will also showcase art installations symbolic of the city by Michael Murphy, Geoff McFetridge and Charles Baker, and dancing by the hip-hop Versa-Style Dance Company.

Dublab, an L.A. nonprofit web radio collective, will provide music, and Fool’s Gold, a Los Angeles Afropop collective, will headline and ring in 2014 with their rendition of “Auld Lang Syne.”

In short, she says, midnight on December 31 promises to be a lot like L.A.—light-hearted, cutting-edge, and—at least lately—a little more interested in community.

“This hasn’t been a place where New Year’s Eve is celebrated collectively, but I think people are more interested in coming together,” says Diamond. “What we’re building is a new tradition for L.A.”

Posted 12/12/13

Making spirits bright

December 6, 2013

The holiday season demands a soundtrack, and for many musicians, this is one of the busiest times of the year.

Just ask Jane Sarture what her ensemble is up to these days.

“We played this morning in a real estate office,” Sarture said. “We’re going to go out to hospitals, senior centers, the Ronald McDonald House charity Christmas party. We’ll be playing at Olive View hospital. We’re going to be at the Kaiser farmer’s market… I don’t think I ever stopped to count yet but I think we have 25 performances across 24 days.”

Sarture is a music director, but she’s not leading a local orchestra, singing group or jazz combo. Her musicians are developmentally disabled adults who play in the ARC Handbell Choir.

Their rendition of “Jingle Bells” may not be the slickest version you’ll hear this season, but it’s undoubtedly the most heartwarming.

“It is inspiring,” said Sarture, 52, a former associate producer of television game shows who switched careers to work at ARC 22 years ago and now accompanies the group on keyboard during their performances.

“The first day I walked in, I was like, “This is so cool.’ It’s like that old cliché: it’s not a job, it’s a calling,” she said of her work at the non-profit ARC (Activities Recreation and Care). The North Hollywood organization offers adults with cognitive disabilities a chance to take part in a wide range of life-enriching activities, from camping and field trips to volunteering at senior centers and even running marathons. The handbell choir is one of the most visible manifestations of the organization’s mission; they’ve performed 11 times since 1999 in the county’s Holiday Celebration, which is broadcast live on KCET. (This video captures one of their previous performances.)

This year, they’re returning to the stage of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion for the 12th time to perform in the annual Christmas Eve extravaganza, produced by the county Arts Commission and featuring an array of performers in many genres. If past experience is any indication, look for the audience to respond to the handbell choir with a rousing ovation—and perhaps a discreet tear or two.

“People are amazed,” said Jennifer Davis, an ARC employee who conducts the ensemble’s performances and also serves as the organization’s volunteer marathon coach. She ran the New York Marathon this year with ARC client Jimmy Jenson, who has Down syndrome and received national acclaim on the “Today” show for his accomplishment.

“A lot of times people see the young, cute babies and they don’t know what happens [to the developmental disabled] when they grow up,” Davis said. “You’ll see people with tears streaming down their faces and they’ll say ‘I have a six-year-old and to think that my child can grow up and live such a phenomenal life.’ ”

Davis said an overarching message behind the group’s success is a determination to look past what people can’t do and focus instead on what each individual is capable of.

“When we look at what we can do, and what we can contribute, that’s when community and the real music in life happens,” she said.

ARC’s handbell choir has been jingling all the way since 1985 and now performs year-round.

They don’t charge for their performances, but happily accept donations, which Sarture said can range from “a great lunch and a couple of candy canes” to a check for $50 or even $2,000.

It all comes in handy when you’re trying run a handbell choir.

“It’s an expensive operation,” Sarture said. “If you drop a bell, it’s $200.”

There’s plenty of music in the air, but one thing you won’t hear from this group is any complaining about how busy things get when the holidays roll around.

“It’s amazing,” said one performer, 34-year-old Hillary Shaw, after an evening performance at a holiday open house in Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s Van Nuys district office this week.

And as for Sarture? “It’s a blast,” she said. “It’s my favorite time of the year.”

Posted 12/6/13

County has designs on voting

November 13, 2013

IDEO founder David Kelley has melded utility with elegance in his firm's designs for famous clients.

It’s not easy to re-imagine the largest voting system in the nation, but it doesn’t hurt to have the company behind stand-up toothpaste on your team.

For the past year or so, Los Angeles County has been working closely with IDEO, the innovative Bay Area design firm, to help with the county’s multi-faceted initiative to update its antiquated voting apparatus. The challenge is a big one: The county’s system serves some 4.8 million registered voters in 11 languages at some 5,000 polling places, and is currently using technology that dates, in some cases, to the 1960s.

So in an effort to think creatively about the future, the office of the Registrar-Recorder/County Clerk and the committees guiding the county’s Voting Systems Assessment Project reached out to a firm whose groundbreaking design work goes back to Apple’s first computer mouse in the 1980s.

“We wanted to focus on innovation, and we were attracted by their philosophy of design that’s human-centered,” says Efrain Escobedo, governmental and legislative affairs manager for the Registrar-Recorder/County Clerk’s office. IDEO, he says, studies “what the experience is underlying a project—whether it’s a filling station or a vegetable peeler—rather than just designing around what’s cheapest.”

Created as a merger of four design firms—one in Palo Alto, two in San Francisco and one in London—IDEO, which is now global, specializes in cutting-edge product and organizational design. One of its founders, David Kelley, was close friends with the late Apple co-founder Steve Jobs, whose elegant products became a computer industry standard. But IDEO’s work has run the gamut, from upright dispensers for Crest toothpaste to a rethinking of school lunches.

Initially, Escobedo says, the county learned about IDEO during an experiment with crowdsourcing in which the county put out a call for ideas on the future of voting through OpenIDEO, an online platform and community. But in early 2013, after conducting its own extensive data-gathering process, the county engaged the company’s consultants to help analyze the research under a series of short-term agreements worth about $1 million.

Among IDEO’s objectives is a rethinking of the traditional voting machines so they not only accommodate voters in a multiplicity of languages and settings, but are also universally accessible no matter the voter’s age, education, familiarity with the process or physical abilities.

“We’ve delivered three really, really rough concepts that we’re working now to whittle down into one,” says Sarah Rienhoff, IDEO’s public sector lead on the voting project. Visual renderings and mock-ups have ranged from boxy one-stop, hands-free voting stations to lightweight podium-like contraptions that can be easily moved around by poll workers and stored.

To augment data the county gathered, IDEO consultants examined on their own the extremes of the voting spectrum—newly naturalized citizens, older voters, young voters, people who had stopped voting and people with physical limitations that impacted their use of the existing system.

That last group was especially important, in part, because advocacy groups for the disabled have sued over issues such as the lack of touch-screens and the paper ballot requirement—mandates that, they contend, make voting harder and less private for visually-impaired voters.

So, Rienhoff says, the group put a special emphasis on disabled voters. One focus group brought county staffers nearly to tears as a man with cerebral palsy talked about the alienation of being shunted off to vote in a separate booth for handicapped people.

Another exercise took the form of an educational field trip.

“We did ‘dining in the dark’ at Opaque, a restaurant in Santa Monica where all the [servers are] visually impaired or blind and the customers eat in a fully dark dining room,” says Rienhoff, adding that they went back the next day to interview their waiter—one of more than 44 individual interviews they conducted last spring.

The IDEO group also studied lottery kiosks as an example of a system in which decision-making is paired with convenience and observed elections in Pasadena and Compton to compare voting in diverse communities.

What’s more, the firm’s creative approach served to inspire the Registrar-Recorder staff, Escobedo says. Among other things, they created an “idea wall” in the executive office in Norwalk after visiting IDEO’s workspace.

As the project’s self-imposed 2016 deadline approaches, some broad outlines have begun to take shape. For one thing, Escobedo says, it is clear that the new system won’t include voting via Internet or smart phone, at least for now, due to security concerns.

That, however, doesn’t preclude the possibility of the vote-by-mail option morphing someday into a scanned ballot sent by encrypted email, or a digital tablet onto which voters can electronically upload their pre-marked decisions. Also, look for bigger ballots, voting machines with universal design and hands-free access and possibly a voting process that revolves less around a single day at a single polling place than, say, a 2-week voting “window” or community voting centers.

“By the end of the year, we hope, we’ll have an actual final design concept that we can begin to engineer,” says Escobedo, who expects to start prototyping some time next year.

One aspect of the process is unlikely to change, however: That little “I Voted” sticker?

“Oh, that’s a mandatory do-not-leave-out,” laughed Escobedo. “People love that. It’s not going anywhere.”

One possibility for future voters might be more portable voting machines, as seen in this IDEO rendering.

Posted 11/13/13

A beach for one and all

November 7, 2013

When it comes to reinforcing stereotypes of the California dream, few towns can match Manhattan Beach. Its finely-groomed sands draw scores of barely-clad stars of beach volleyball, including Olympic champions. Its waves are crowded with high-flying surfers and its shoreline bikeway is among the region’s most scenic.

But now, thanks to the persistence of a 90-something activist, the South Bay community is clearing the way for a new group of beachgoers to hit the sand, a group that’s certain to grow as baby boomers advance well into their senior years.

On Tuesday, the Board of Supervisors approved the drafting of an agreement between the city of Manhattan Beach and the county’s Department of Beaches and Harbors for the construction of a “Path to the Sea” that will provide access on the sand for people with disabilities.

Already, Santa Monica has two access ramps across the sand near the pier that stop short of the water, one made of wooden planks, the other of recycled tires. There’s also one that travels alongside the north jetty and at “Mothers Beach” in Marina del Rey.

But the permanent concrete path proposed for Manhattan Beach, which juts directly onto the sand, is the first of its kind for southern Los Angeles County-operated beaches. It will be located at the city’s northern end near the popular El Porto parking lot, where wheelchair ramps currently exist. From there, the 10-foot-wide path will extend 70 feet onto the beach, with a broad turnaround at the end, about 150 feet from the water’s edge.

The project represents an “a very interesting experiment” that poses challenges unmatched by other kinds of access for disabled people, said Chief Deputy Director Kerry Silverstrom of the Department of Beaches and Harbors. Foremost among those, she said, was determining how to construct a permanent path that won’t be undermined by eroding sand or damaged by tractors that drag the beach for trash.

“The beach is a natural resource that should benefit everybody,” Silverstrom said. “But it’s particularly complicated with urban beaches where a lot of grooming occurs…It’s hard enough to keep a bike path maintained. How do you keep these kinds of walkways maintained and free of sand for people who need them?”

Logistical questions like these kept the project on the drawing board for years, to the frustration of neighborhood activist Evelyn Fry, 98, the driving force behind the walkway, which will be constructed by Manhattan Beach, at an estimated cost of between $33,000 and $38,000, but cleaned daily by the county.

Fry, who is not herself disabled, championed the path as part of her active participation for decades in the civic life of the community, to which she moved in 1938. She could not be reached to discuss her latest success.

According to Manhattan Beach engineering technician Ish Medrano, Fry wanted the concrete path to extend to the shore’s edge. But that wasn’t possible, he said, because of the possibility of it being washed away by the surging sea. “I think she’s going to be a little disappointed,” Medrano said of Fry, who became so well known at City Hall that when she walked through the door “it was like an alarm going off: ‘Evelyn’s here!’”

Medrano described Fry as “the nicest woman” but “relentless” in her six-year crusade. “I think she’d like to see it completed before she passes away,” Medrano said, quickly adding: “She’s joked about that herself.”

Posted 11/7/13

Kitty cat 90210

October 24, 2013

Even a cat can dream big in this town. Take Harry. Just five months ago, he was wandering the alleys. Now he lives in a landmark 6.5-acre Beverly Hills estate.

At the Virginia Robinson Gardens, a 102-year-old historic property owned by Los Angeles County, staffers say the white stray with the black tail and ear has been an unofficial colleague since April.

“He just showed up one day and started following one of the gardeners around,” said Superintendent Timothy Lindsay on a recent morning. “He was very friendly, very domesticated—and very vocal.”

“Meoooow,” confirmed Harry, glancing up from the tiled Italianate pool, where he appeared to be alternately drinking and scouring the blue water for signs of sea life.

“He likes to think there are fish in there,” whispered Lindsay.

Harry switched his tail. Lindsay said he was recently named Chief Mouser and Rat Patrol.

The property, built by the heir to the Robinson’s Department Store fortune and bequeathed to the county after his widow’s death in 1977, is a paradise, even by non-cat standards. A national, state and local landmark, it is now operated by the county Department of Parks and Recreation and supported by the nonprofit Friends of Robinson Gardens as one of Los Angeles County’s first great estates.

The owners, Harry and Virginia Robinson, were community pillars in L.A. for decades, famed for their star-studded parties, their elaborate landscaping and the many pets on whom they lavished attention.

“I think they were more dog people,” Lindsay said, noting the canine paw prints in the concrete walks connecting the estate’s five gardens. “And they had 300 blue songbirds that she imported from New Zealand, and a toucan that spent time on the loggia, eavesdropping on all the Hollywood gossip.”

But Lindsay said the cat, who sauntered in without even a microchip of identification, had such a confident air that the gardens staff named him after the estate’s founder. After a student working on the grounds volunteered to take him to the veterinarian to make sure he was vaccinated against rabies, the staff and live-in groundskeeper took him in and started to feed him.

“He’s a great mouser, and averages two a day,” says Lindsay. “He brings them to the kitchen door and drops them. And he’s so entertaining—he flops over like a dog and wants you to rub his belly. He sleeps in the laundry room in the staff quarters adjacent to the main house. We have a little bed for him.”

Harry isn’t the only creature to have adopted the gardens, says Lindsay. Coyotes drop in occasionally, and two horned owls have taken up residence in the estate’s King Palm grove. But, he says, the cat is the estate’s only domestic pet.

“He’s made this his house,” Lindsay said as Harry trotted across the flossy emerald lawn, settling in for a nap near the Renaissance Revival pool pavilion, which was modeled after Italy’s famed Villa Pisani. “The cat’s no dummy. He picked the nicest place in the neighborhood.”

Posted 10/24/13

Grand Park comes of age

October 3, 2013

They built it. And they came.

This week marks the one-year anniversary of downtown’s Grand Park, a four-block expanse that has provided a jolt to Los Angeles’ Civic Center for reasons well beyond its hot-pink furniture.

Since its dedication last October, the 12-acre park between the Music Center and City Hall has drawn tens of thousands visitors for events big and small, from a Fourth of July extravaganza to daily yoga classes. Although the big-city development around it continues to be vigorously debated, the park itself has proven to be an intimately scaled magnet for families and children. The “splash pad” at the Arthur J. Will Memorial Fountain, in particular, has drawn knee-high youngsters and their parents from across the region.

“It’s just as serene and beautiful as I expected,” said Kesha Barkulis, who, on a recent and sparkling autumn weekday, was following her drenched and teetering 9-month-old daughter, Luna, as she navigated the 79 gentle water jets of the fountain.

It was their first visit to Grand Park, one that Barkulis said she’d wanted to make all summer, ever since reading about the ¼-inch-deep pool on a website aimed at moms seeking kid-friendly outings. They had taken the Red Line subway from North Hollywood to the Civic Center station, located just steps away from the fountain, which has become a popular venue for toddler birthday parties now.

For decades, the area formerly known as the “Civic Center Mall” was largely hidden by concrete parking ramps and two blockish government buildings—the Superior Court and Los Angeles County Hall of Administration. As a result, the mall and its 1960s-era fountain ended up being used mostly as an outdoor break area for bureaucrats and jurors.

But after a $56-million privately-financed makeover, which was required as part of the approval process for commercial development along Grand Avenue, the park is now generating crowds—and buzz—through a mix of programming experiments overseen by the Music Center.

The Fourth of July event, for example, drew an estimated 10,000 people, according to Grand Park Programming Director Julia Diamond. Thousands of people, she said, also have shown up for dance events and a movie series featuring such family fare as “ET” and “The Never Ending Story.” Last Sunday, 2,000 music fans gathered on a Grand Park lawn to watch the first simulcast of a Walt Disney Concert Hall performance, which featured jazz great Herbie Hancock.

Not bad for Year One.

“People think of Angelenos as wanting to celebrate privately,” Diamond said. “But people in L.A. are game for sharing.”

The park, which she called a “cultural and civic space with no walls,” has tapped into that growing hunger for collective experiences, exemplified by the widely popular CicLAvia events.

One key to the park’s early success, Diamond said, is that thousands of people in offices and lofts downtown “have actually shown a large appetite for diversion and entertainment in the middle of the day, uniting around something that speaks to a part of themselves outside of their work lives.” Besides lunchtime yoga and informational fairs on such topics as green transportation and public health, the mid-day programming has included a weekly farmer’s market and concerts ranging from Latin jazz to classical music to pop.

Diamond said she’s also been struck by the ethnic and economic diversity of the visitors—a result, she suggested, of having a park without a strong neighborhood history or existing identity. “This gives the park a lot of freedom to be whatever people want it to be,” she said.

Still, not everything’s gone as the programmers had hoped. One of the biggest first-year challenges, Diamond said, has been to get the downtown workers to become an after-hours crowd. “They get into their cars and drive away,” she said, adding: “If you gave people a reason to stay, they would. We haven’t found that reason yet.” (One possible reason: Grand Park’s official 1st birthday bash, which takes place from 7 p.m.-10 p.m. on Thursday, Oct. 10, and features free entertainment on the Performance Lawn.)

Diamond said Grand Park programmers and marketers also have been stymied by the nature of downtown itself, which she described as “sort of like the Balkans.” The farther away from Grand Park people work, such as in the Bunker Hill area, the harder they are to engage. Downtowners, she said, “tend to stay in their micro-community.”

Diamond’s anniversary wish for the next year?

“I want everyone in Los Angeles to know about Grand Park,” she declared. “A year ago, we didn’t exist. I want that name to have instant recognition as an amazing place.”

Grand Park's music events have proven particularly successful in drawing crowds during the first year.

Posted 10/3/13

New law puts bike czar in rider’s seat

September 26, 2013

Senior bike coordinator Michelle Mowery has seen a sea change in attitudes about biking in Los Angeles.

You’ve got to hand it to Michelle Mowery. For two decades, she’s persevered, holding the job of “bicycle coordinator” in the nation’s most car crazy city. “A candle in the wind,” she calls herself. Make that a hard-blowing headwind.

But now, almost overnight, Mowery’s mandate has found a powerful constituency in City Hall and on the roads, giving her once-invisible position in the Los Angeles City Department of Transportation rising stature.

“We’ve put in more bike lanes in the past two years than during my entire career here,” she says. “We have a lot of work to do, but we’re getting stuff done.”

The latest achievement came this week, when Gov. Jerry Brown signed a law requiring California motorists to stay at least 3 feet away from cyclists when passing—a requirement already in effect in 22 other states. Four earlier versions of the measure had died because of various safety and liability concerns.

When Mowery heard the news on Monday, she says one word came to mind: “Finally.” For years, she had championed such a law, alongside elected officials in Los Angeles and bicycle advocates statewide. She praises the measure as “a start and an acknowledgement that cyclists need that little bit of space to stay safe.” It will take effect next September.

When Mowery heard the news on Monday, she says one word came to mind: “Finally.” For years, she had championed such a law, alongside elected officials in Los Angeles and bicycle advocates statewide. She praises the measure as “a start and an acknowledgement that cyclists need that little bit of space to stay safe.” It will take effect next September.

According to the California Bicycle Coalition, which launched a “Give Me 3” campaign with Los Angeles advocates to give visibility to the issue, passing-from-behind collisions are the state’s leading cause of bicyclist fatalities. In fact, Mowery says, a galvanizing moment in the long effort to win passage of a buffer zone for cyclists came in 2006, after popular UC Santa Barbara triathlete Kendra Payne was struck and killed by an asphalt truck that tried to pass her on a sharply-curving road.

Mowery says existing California law simply states that drivers must keep a “safe distance” when passing cyclists, a subjective standard. Now, she says, law enforcement has been given a specific tool to cite motorists who invade a rider’s legal space. Even if police don’t make enforcement a top priority, the legislation’s educational value alone could save lives, says Mowery, a lifelong cyclist who’s now 54. She added that this is especially true in Los Angeles, where riders often need more room to dodge bad pavement conditions. “They’re not always able to ride in a straight line,” she says.

Mowery attributes the growing clout of cyclists to shifting demographics. She says that when baby-boomers like her learned to drive, the region’s freeways were new “and wide open. It was the land of opportunity for cars.” These days, however, the under-30-crowd is driving less, while increasing numbers of teenagers are deciding not to even get drivers licenses.

“They see people sitting in traffic and it doesn’t look like fun,” Mowery says.

Eric Bruins, planning and policy director of the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition, agrees, calling this “a golden era for bikes.” The new buffer-zone law, he says, is a “huge” step forward. “For us on the street, this is something we encounter every single day. Everybody just needs a better understanding of what it means to pass safely, and that’s what this law provides.”

Bruins credits Mowery with being a leading force behind the new law through her advocacy in Los Angeles and as a member of statewide cycling organizations. “I don’t think the bike community has understood what a quiet champion she has been…She’s been trying to get this [law] passed forever.”

Bruins says that, for years, Mowery had been a controversial figure, the public face of City Hall recalcitrance to demands for more bike friendly streets. But now, with the growing influence of Los Angeles cyclists, Bruins says, the city’s bike boss is riding high.

Says Bruins: “She is finally empowered to do her job.”

Posted 9/26/13

On kids’ side against sex traffickers

September 18, 2013

Michelle Guymon understands why people pass by the children on the boulevards, looking but not really seeing youthful lives shrouded in peril and despair.

For years, she did it herself.

“I’ve seen young girls on the side of the road,” said Guymon, who joined the county’s Probation Department in 1989. “There comes a time in your life when you don’t even pay attention to that anymore because you’re on the phone, you’re on your way to work, you’re focused on the street lights…You just drive by stuff.”

She’s not just driving by anymore. Three weeks ago, Guymon was named the first director of the county’s Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking Project. She’s determined to help the system—and the public—see the grim reality of underage girls, some as young as 10 years old, being victimized by the sex trade.

Guymon, 52, said her own awakening was a long time coming. For years, like others in the criminal justice system, she had taken a dim view of those girls by the side of the road.

“I had looked at these young women as teenage prostitutes, and this was just the crime they committed, like this girl over here committed a crime for robbery,” she says. “And I remember having judgments about them, that this was their fault, this was their choice.”

An unexpected assignment to a subcommittee on underage sex trafficking in 2010 shook her world view. At first, she was puzzled by the terminology being used, assuming that “trafficking” was something that just happened to kids from faraway countries.

When she attended the first meeting, she discovered that everything she thought she knew was wrong.

“It wasn’t until that moment when I realized, oh my gosh, you mean these kids are not teenage prostitutes? They’re not out doing this and making lots of money as a career choice?” she said. “They’re being what we’d consider sexually exploited. It was a defining moment for me.”

Instead of being victims of shadowy international sex trafficking rings, young girls here in Los Angeles, she found, are being sold into what some have called sexual slavery by local street gangs and other opportunistic homegrown criminals.

Now those girls had a champion, on the inside.

“She is probably one of the most committed, action-oriented and solution-focused persons that I have worked with in a very long time,” said Fesia Davenport, chief deputy director of the county’s Department of Children and Family Services, which is developing its own plan to attack the problem as part of the countywide effort. “She doesn’t have any egotistical skin in the game. She’s willing to take a good idea from anyone.”

Working with a colleague, Hania Cardenas, Guymon began dedicating herself to the issue—even though both she and Cardenas were also working demanding fulltime jobs within Probation.

In the three years since then, the county, with Probation at the forefront, has emerged as a leader in raising consciousness about underage girls being trafficked. Guymon estimates that her department alone currently has 435 sex trafficking victims under the age of 18 currently under its supervision, with some 3,000 more between the ages of 18 and 24.

Even as officials continue to gather data to get a better handle on the scope of the problem, initiatives—like a special “Girls’ Court” in Compton—have been launched to help surround young victims of sexual exploitation with supportive services and the kinds of human connections needed to break the bonds they’ve developed with their pimps.

Commissioner Catherine J. Pratt of the Girls’ Court said it is essential to have someone in Guymon’s position to keep the momentum going. “There’s a lot of system change that we need to do,” she said. “And she’s a wonderful person for it.”

Guymon’s small team—herself plus “a mighty three” probation officers—are focused on building that kind of trust. “These kids have my probation staff on speed dial, 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” she said.

Monthly training sessions at a hotel in Downey have now reached nearly 3,000 county employees and community activists, with a waiting list stretching through November.

The Board of Supervisors recently unanimously voted to urge the state to increase penalties for men who pay for sex with underage girls—including higher fines and a requirement that they register as sex offenders. Guymon testified in favor of the action, along with officials including District Attorney Jackie Lacey and Long Beach Police Chief Jim McDonnell, who said that local gangs’ involvement in sex trafficking is similar to their incursion into the narcotics trade in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s.

Ultimately, Guymon believes the state should decriminalize prostitution for girls under 18 years of age. But she acknowledges there’s a long way to go before the system is ready to deal with all the “unintended consequences” that might result.

In the meantime, she and a cross-departmental team are pushing forward to develop new protocols and practices to attack the problem.

“Once you know better, you have to do better,” she said. “You’ve gotta do something. You can’t ignore it. Our kids are counting on us.”

Probation Chief Jerry Powers said he named Guymon to her new post because the scope of her work on the problem had “mushroomed.”

“Even having been in the profession as long as I’ve been it, I would have never guessed it was as significant as it’s turned out to be,” Powers said. “Michelle’s work has helped us understand the complexity of the issue and the magnitude of it.”

“I think she’s awesome,” added Cardenas, her probation colleague and partner in the effort. “We always laugh about how we complement each other so well. She’s so outspoken. She likes to present. I’m a better writer. She kind of ended up being the face of it, which is her strength.”

The oldest of seven children, Guymon grew up in St. George, Utah, aspiring to play college basketball and ultimately to become a women’s basketball coach at the university level.

She went on to compete in college but found another, more satisfying, court to play on when she accepted an invitation to become the recreation director at a boys’ group home. Eventually, that work led her to a job with the Los Angeles County Probation Department. Looking back now, Guymon, who has a bachelor’s degree and master’s of social work from Cal State San Bernardino, knows she made the right move.

“Life threw me a curveball and I was just hooked,” she said. “I really am a kid junkie on some level. I feel like it’s where I’m supposed to be.”

Posted 9/18/13

Check for the latest closure information

Check for the latest closure information