From the ashes, monumental memories

November 20, 2012

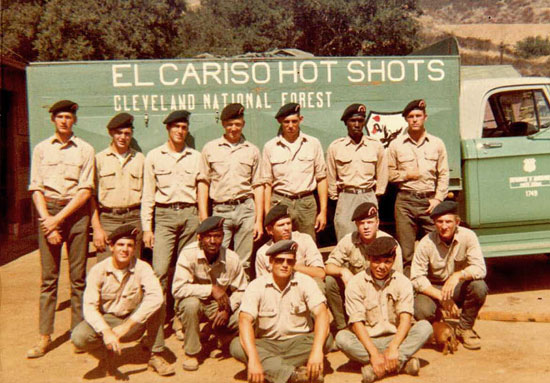

Rich Leak, in front with sunglasses, in the year of the Loop Fire. Five fellow "Hotshots" in this picture died.

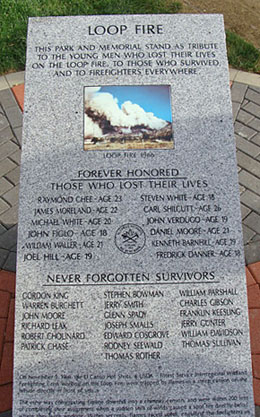

Last week, a memorial was relocated in the San Fernando Valley, a bit of granite that was moved for improvements at El Cariso Community Regional Park. The marker is modest, standing in sharp contrast to the tragedy it commemorates: Forty-six years ago this month, 31 young men were dispatched to a wildfire near Sylmar, and only 19 of them survived.

Rich Leak was 19 that summer, the gung-ho son of a Camp Pendleton fire captain. “All my life,” he recalls “I had wanted to be a fireman.” After attending a summer firefighting program at the U.S. Marine base, he had joined an elite ground crew of “hotshots” based near Lake Elsinore, so called because they were dispatched to the hottest parts of forest blazes. By 1966, his second year with the El Cariso Hotshots, he was a crew foreman, traveling the West to cut fire lines and clear brush around raging wildfires and “loving the excitement and the adrenalin rush.”

The Nov. 1, 1966, call came on a hot day at the end of a long fire season: A faulty power line had sparked a brushfire near Pacoima Dam. Whipped by Santa Ana winds, the blaze had charred some 2,000 acres around Loop Canyon. But it appeared to be dying by the time Leak and his fellow hotshots got what they regarded as an easy assignment—to scrape a fire line along a ravine near the smoldering fire.

“There wasn’t a lot of brush, and the fire was starting to lay down, so the line we were cutting didn’t have to be that big,” Leak remembers. The young men worked without gloves, their hands thick and calloused, their shirtsleeves rolled up. Their orange fire shirts had been washed so many times that they had long since lost their fire retardant coating. No one carried a radio or stood lookout. No one bothered to haul in a portable fire shelter.

And no one understood the dangers of the terrain, Leak says. Now firefighters know that a steep crease in a slope can act as a draft for combustible gasses. But on that day, no one knew that the 31 guys in orange hardhats were entering a death trap. They were nearly done with their work when, at 3:35 p.m., the wind abruptly shifted. A spot fire ignited on the hillside below them. As Leak looked up, the air around him suddenly went wavy.

Down the line an order came: Get out—now! But within seconds, a mighty rush of super-hot gas swept up the 2,200-foot ravine and exploded.

“It was like when you pour lighter fluid on a charcoal barbeque and put a match to it,” Leak remembers. “There was this big wooooof! And then all I could see was just a wall of orange flame. I had to look straight up to see blue sky.”

Leak held his breath so his lungs wouldn’t sear in the 2,500-degree heat, falling to his knees as the shock wave hit him. “Guys were yelling and screaming and praying and calling for their mothers,” he remembers. “I was talking to my Savior, that’s for sure.”

The Loop Fire would change safety protocols for fighting fires in narrow canyons, encouraging lookouts and radios and the development of much-improved fire gear, but not before it claimed the lives of 12 hotshots, most in their late teens and early 20s. Ten more were critically burned and scarred for life by the disaster. The fireball lasted no longer than 60 seconds, but in that time Leak suffered full-circumference burns from his elbows to his wrists, and lost four of his fingers.

After the smoke cleared, he recalls, “I was in shock, running around from one guy to the next, trying to put out the fire with my bare hands. At one point, I looked down at my arms and saw skin hanging down. All I thought was, ‘Wow, I guess I got burned pretty good.’”

It took three years and more than 30 surgeries for doctors to repair Leak’s wounds, using skin grafts from his stomach to repair his damaged hands. He has had to relearn how to type and eat with utensils. He struggles to pick up coins and he has to use both hands to screw a hose onto a faucet. He has no fingerprints.

“For a long time, I was very self-conscious,” he remembers. He went back to school at Palomar College near his hometown of Vista, earning an associate degree in business, thinking he might become a CPA. Then he heard the Vista Fire Department was hiring dispatchers. “It’s hard to describe unless you’re a firefighter,” he says. “It never goes away for me.”

He spent 30 years with the Vista Fire Department, working his way up to fire investigator before retiring to Hesperia 12 years ago. He married a friend’s neighbor and helped raise her two children. “To her, it was what was in my heart that mattered,” he says. “She told me she didn’t even notice I was burned at first.”

Then in 1996, the U.S. Forest Service sent him a notification: A memorial commemorating the 30th anniversary of the Loop Fire was going to be installed in El Cariso Park. Not all the survivors could make it, but some did. Sadly, they recalled the fallen.

“I still remember ‘em,” Leak says. “Raymond Chee, my crew boss, a Navajo I think from New Mexico—very quiet guy, used a brush hook. He was the best hook I’ve ever seen. The White brothers, Michael and Stephen, 22 and 18. They were from San Diego. Their dad was a captain in the Navy. It was devastating for their family.

“John Figlo, he was 18, kind of a quiet guy. Strong. James Moreland. He was in his twenties. Frederick Danner, a tall guy and a really good worker. He died in the hospital. Kenneth Barnhill, nice guy. I knew his brother. Carl Shilcutt, he was 26, one of the older guys on the crew.” He continues down the list: Daniel Moore, Joel Hill, William Waller. John Verdugo, a 19-year-old kid whose body was the first one he saw when he opened his eyes.

Leak kept in touch with the other survivors. He and another ex-hotshot, Ed Cosgrove, began giving talks together to fire academy classes. There were reunions—that’s how he found out that the 1996 marker was in serious need of repair. A drunk driver had hit it and cracked the granite. Skateboarders had worn down the lettering; taggers had marred it with graffiti.

So Leak spearheaded a move for a new one, only to learn that it was going to be moved anyway to make way for park improvements. Last week, a new marker was re-dedicated near a park office building. “It’s near a walkway,” he says. “Granite, just like the original.”

“There are times when I think, ‘What if I’d perished?’” says Leak, now 65. “But you can’t let things haunt you. You have to get over your injuries and go for it. I’m thankful to be here, living my life.”

Posted 11/7/12

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink