Urgent need, serene space

August 11, 2011

Most of us are familiar with “urgent care” as the place to go when a medical situation’s not dire enough for the emergency room—but too serious to ignore.

Now apply that concept to mental health issues and you’ll have a picture of what the county’s now offering in a newly-opened facility.

The Olive View Community Mental Health Urgent Care Center, located at 14659 Olive View Drive in Sylmar, is expected to serve 5,000 people a year and to relieve crowding in the psychiatric emergency room of the nearby Olive View-UCLA Medical Center by assessing and treating patients in psychological distress, as well as helping them to swiftly secure follow-up care.

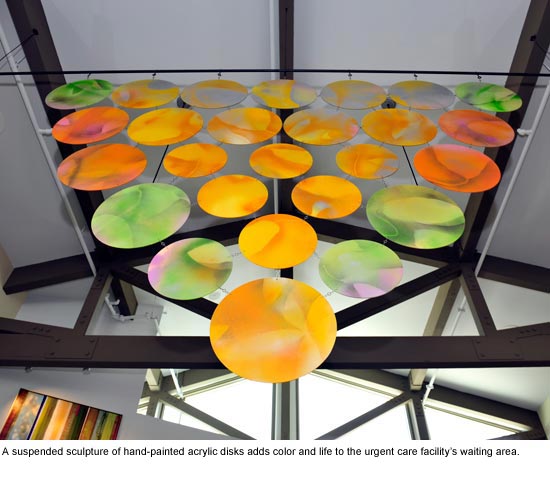

The facility is not just state of the art, it’s full of art—funded under the county’s Civic Art policy and created by Amy Trachtenberg and Jeffrey Miller. Artful elements in the new center explore bright yet soothing motifs, imbued with natural elements. The message—architecturally, artistically and clinically—is one of healing and hope.

The $10.8 million, 10,800-square-foot project—which has earned LEED silver certification—will serve clients from the San Fernando, Santa Clarita and Antelope Valleys. The new facility will allow the county to serve an additional 2,000 people a year. Its opening comes as economic pressures and joblessness are adding stress to the lives of many.

“Opening this new mental health facility today could not have come at a better time. It’s not a moment too soon,” Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky said. “Demand for our services is going up.”

Here’s a look at the new facility, inside and out:

Posted 8/11/11

An artful setting for an urgent mission

March 10, 2010

When artists meet with mental health clients to get a sense of how a psychiatric urgent care center should look and feel, the clients don’t hold back.

“Don’t use any really bright colors—and definitely don’t use any red.”

“Being in nature makes us calm down and feel good.”

And that institutional grey metal file cabinet over there? “That is exactly what we don’t want to see.”

For artists Amy Trachtenberg and Jeffrey Miller, those conversations were a welcome validation of many of their ideas on color, nature, material and mood.

They also form an essential element in an extraordinary collaboration that will begin to take shape later this month when construction begins in Sylmar on the new facility, with the proposed name the Olive View Community Urgent Care Center.

Not so long ago, the aesthetics associated with mental health facilities were at best coldly clinical, at worst something out of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

The Olive View project aims to make a sharp break with all that.

The Mission-style project, which breaks ground on March 17, is the culmination of years of work by a county team that has made art and design central to its exploration of how the look and feel of the new building itself can play a role in the treatment of patients in psychological distress.

From color palette to carpet pattern, no detail has been too small for the county team working with the artists and architects HMC and gkkworks. The multifaceted working group includes representatives from the departments of mental health and public works, the arts commission and deputies from the offices of Supervisors Zev Yaroslavsky and Michael D. Antonovich. (A 2004 motion by Yaroslavsky, followed by another motion he authored with Antonovich a few weeks later, got things rolling on bringing psychiatric urgent care to an underserved area.)

The new facility is part of a larger movement to bring high-quality art into hospitals and other health care facilities not just as decoration, but to help in the treatment process.

Diane Brown, the founder of RxArt, a New York nonprofit that specializes in bringing contemporary art into medical settings across the country, says that hospitals were wary when they started nearly 10 years ago.

“When we did our first project, we had a hard time getting our foot in the door,” Brown says. “It was free, museum-quality art, and we couldn’t give this stuff away…Now hospitals call us up. We don’t have to beg anybody.”

RxArt, which is planning to place a Jeff Koons installation in the CAT scan room of a children’s hospital in Chicago, has worked on an inpatient psychiatric ward and has an upcoming mental health urgent care project of its own coming up, at New York’s Kings County Hospital.

“You have to be so careful with what you’re putting in,” Brown says of such projects. “Something I thought was perfect was just completely inappropriate.”

On the opposite coast, such considerations are front and center during a meeting to determine tile, paint and flooring choices for the new Olive View urgent care. A certain shade of green draws comments like “I’m thinking psychiatric hospital circa-1965 throwback.”

At the same meeting, someone asks whether blue should be ruled out as a “depressive” color.

James Coomes, the mental health department’s program head for Olive View urgent care, quickly responds to that one, saying that in this kind of treatment setting, “it’s really the bright red that we were concerned about. If someone’s agitated, we want to bring them down.”

Such nuances are crucial when you’re creating a space for the relatively new concept of mental health urgent care. The facility must serve patients too troubled to wait weeks for a simple counseling session but who may not need full-on psychiatric emergency room treatment. Clients could be people experiencing the onset of schizophrenia, a serious bout of depression, or a traumatic event. Many, if not most, have substance abuse problems as well.

“We can decompress the psychiatric ER [at Olive View-UCLA Medical Center] if we do our job right,” Coomes says.

Even without a permanent home, the county’s mental health urgent care operation in the San Fernando Valley has been seeing a growing caseload: from 832 cases in 2006 to 1,570 cases last year.

One of those clients, William O’Reilly, says the urgent care staff threw him a lifeline when he was in the throes of a profound depression.

“That place saved my life,” says O’Reilly, 47. “There was so much compassion shown…That’s fantastic that there’s going to be a new facility.” When the new urgent care opens, the county aims to treat more than 3,000 clients a year there.

The input from clients—part of a day-long tour for the artists–came from residents at the county’s Hillview intensive residential center, for homeless people who have received mental health treatment.

“This was really quite a wonderful thing for us,” Trachtenberg says. “We got to learn the kinds of things they are drawn to and what repels them.”

The artists—who are a married couple as well as professional partners on this project—say they drew on a wide range of influences, from Ayurvedic medicine to “sacred geometry” and classical allusions, to create the Olive View plan.

“Our goal is to try to create a kind of calming, restorative place,” Trachtenberg says. “We really drew from various cultures…timeless forms, ancient forms, a response to nature and to geometry—an approach both ornamental and restorative that hopefully will lift the spirit.”

“The staff was important, too,” says Miller, who is also a landscape architect. “They were making sure we were aware of certain color relationships.”

While psychiatric urgent care is offered elsewhere in the county, including St. John’s Hospital in Santa Monica and the Augustus F. Hawkins Mental Health Center in South Los Angeles, Olive View will be the first stand-alone facility to be built specifically for that purpose.

The $10.8 million, 10,800-square-foot project—which aims for LEED silver certification for its environmentally sensitive building practices—is also the first in the county to incorporate the artists’ concepts in the plan from the very beginning of the process.

The $10.8 million, 10,800-square-foot project—which aims for LEED silver certification for its environmentally sensitive building practices—is also the first in the county to incorporate the artists’ concepts in the plan from the very beginning of the process.

“It’s really been great having this team effort—not just coming in after the fact and plunking in some art,” says Carrie Brown, a civic art project manager for the county Arts Commission who has been working on the Olive View project for the past three years.

Integrating art into new projects took off with the enactment of the county’s civic art policy in 2004. Since the 2005-2006 fiscal year, 1% of the design and construction budget for capital projects must be allocated to art in and around the new developments.

When it came to selecting the artists for Olive View, the San Francisco-based Trachtenberg and Miller drew high marks for their experience. They’ve previously worked on projects including an atrium at Children’s Hospital in Oakland and a multi-faceted art installation for the rotunda of the Hillview Library in San Jose. Trachtenberg also served as the sole visual artist on a mayoral advisory panel for the suicide barrier on the Golden Gate Bridge.

But in the end, it was their artistic approach as much as their track record that won over the staff at the department of mental health.

In fact, mental health staffers were amazed when they first saw the interlocking circles motif incorporated into the project’s signature stepping stones.

Had the artists gotten a look at their treatment playbook?

The design looked like a direct homage to the “family systems theory” pattern at the heart of their therapeutic model—in which patients are linked with family and other support sources.

“They were sure that we had studied their diagrams,” Trachtenberg says.

Work on the Olive View art elements—which, in addition to the stepping stones, will include a painted frieze on wood panels, suspended sculpture, and a 49-foot “horizon sliver” composed of polycarbonate panels—is set to begin this summer. Trachtenberg and Miller are planning to install their work right after construction finishes in the summer of 2011.

The new facility can’t open soon enough for the staffers who will work there.

It’s been five years now since the phalanx of psychiatrists, social workers and nurses, caseworkers and community workers attached to the urgent care program squeezed into “temporary” borrowed space at the San Fernando Mental Health Center. That has meant five years of working in “submarine-like conditions,” often with little privacy as they seek to diagnose, treat and refer desperately troubled clients.

“This is stolen space. Actually, more begged and borrowed space,” Coomes says on a tour of the facility, introducing a small team of case managers and community workers charged with staying in touch with clients and making sure they are scheduled for follow-up visits.

The group’s supervising psychiatrist, Dr. Jeffrey Marsh, recently gave up his office to a junior colleague who sees more patients than he does. Marsh has a cubicle now. As for ambiance, well, it’s safe to say that a high point may be the Sigmund Freud action figure he’s put up on the wall.

Working conditions aside, what’s most important to Coomes, Marsh and their colleagues is being able to offer clients—and their families—a tranquil and healing environment to come to at a frightening and stressful time.

“To create an atmosphere that’s safe, calm and pleasant is really important for the population,” Marsh says. “There aren’t a lot of places like that.”

Posted 3/10/10

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink