Framing the future of L.A. art

November 14, 2014

It’s been dubbed L.A.’s living room, and the coming transformation of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art promises that, artistically speaking, we’ll be living large for generations to come.

LACMA embarked on an ambitious new course recently with the announcement of the largest art gift in its history from entertainment mogul A. Jerrold Perenchio, just a day after the county Board of Supervisors unanimously gave conceptual approval to a plan to help fund a dramatic new Wilshire Boulevard-spanning museum building by acclaimed architect Peter Zumthor.

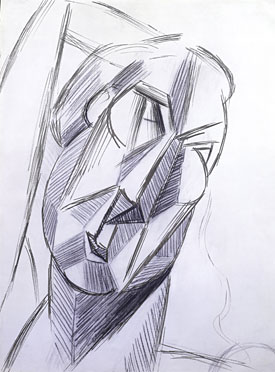

Perenchio’s collection includes spectacular but until now rarely-seen works by a range of celebrated European artists, including Claude Monet, Pablo Picasso, Edgar Degas, Edouard Manet and René Magritte. The 47 works are to join LACMA’s collection following Perenchio’s death, but the public will have a chance to view some of them at a special exhibition next spring, when the museum celebrates its 50th anniversary.

The infusion of art and architecture comes as LACMA’s attendance is surging and the rest of Los Angeles County’s cultural landscape is enjoying exponential growth.

“What’s happening here at LACMA is really emblematic of what’s happening in arts and culture in Los Angeles County and the region,” Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky said, ticking off a 15-year run that has included two new pavilions at LACMA, the opening of Walt Disney Concert Hall, extensive renovations to the county’s Natural History Museum and the Hollywood Bowl, establishment of the Colburn Conservatory of Music and the debut of a new Valley Performing Arts Center at Cal State Northridge, among other highlights.

“If we had just done one of them, or two of them, we would have called it a good decade and a half. But we’ve had all of them,” Yaroslavsky said.

There’s more in store. The Hollywood Bowl this winter will be finishing a series of inside-the-amphitheatre improvements that already have brought patrons amenities like LED screens, updated picnic furniture and new bench seats. The county’s Ford Amphitheatre has embarked on an ambitious overhaul to replace its stage, shore up and re-landscape its scenic hillside and create a striking new terrace dining-and-concession area. On LACMA’s west campus, a new movie museum is about to rise. And LA Opera has launched a new tradition of bringing free, live outdoor simulcasts to audiences outside the Civic Center.

Nowhere is the excitement more visible than at LACMA. Yaroslavsky has coined the term “L.A.’s living room” to describe the museum campus’ around-the-clock pull on visitors, who make themselves at home with activities ranging from outdoor summer jazz to school field trips to photo ops in front of Urban Light to early morning jogs under Levitated Mass.

“When you come here even at 6 in the morning, as I do from time to time, or at midnight, this place is humming,” Yaroslavsky said.

Since the arrival of director Michael Govan in 2006, the museum has made Chris Burden’s Urban Light a crowd-pleasing beacon along Wilshire, created a communal touchstone across Southern California with the rolling of the massive boulder at the heart of Michael Heizer’s Levitated Mass, and doubled its attendance to 1.2 million annually.

Now things are about to get really interesting.

The masterpieces in the Perenchio collection will make their permanent home in the new building being designed by Swiss architect Zumthor, winner of the 2009 Pritzker Prize.

If all goes as planned, the sinuously curved new building should be completed by 2023, just as the Purple Line subway extension reaches the museum as part of its westward march.

The trifecta of the new building, the masterworks from the Perenchio collection and the arrival of the subway promises to accelerate LACMA’s momentum well into the future.

“The museum has become a cultural force in the community, and the Zumthor building will carry it into the 21st Century and beyond,” Perenchio, 83, said at the news conference celebrating his gift to the county museum.

Perenchio, the former chairman and CEO of Univision, has made previous donations anonymously. He said he went public this time in hopes of spurring others to contribute artworks and money to LACMA as it prepares to build the new structure.

Under the plan unanimously approved by the Board of Supervisors, the county has agreed to provide $125 million for the new building, which would replace four aging structures on the museum’s campus. But under the agreement, LACMA’s board must raise $475 million in private funding to make the building a reality. Perenchio said he hoped his gift would “encourage all types of donations, large and small—hopefully more large than small.”

“We have to make the Peter Zumthor building a reality,” he said. “Failure’s not an option here. We’ve got to do it, for the city and everybody who lives here.”

Posted 11/14/14

New LACMA design spans Wilshire

July 3, 2014

Two Los Angeles County museums’ unique but conflicting visions for the future were enough to send an internationally renowned architect back to the drawing board—literally. Now, after a collaborative process that included exploring the grounds of the La Brea Tar Pits with scientists, architect Peter Zumthor is back with a bold new approach for a signature building at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art that avoids the famed Ice Age fossil trove and instead creates a dramatic bridge across Wilshire Boulevard.

Zumthor’s new design for the most part preserves his original concept: a largely transparent building with a shape reminiscent of a curvaceous tar pit. But instead of constructing the entire 400,000-square-foot building on the Hancock Park campus that LACMA shares with the tar pits, he now proposes having one quarter of the structure reach south across Wilshire to what’s currently the museum’s Spaulding Avenue parking lot. One of the new building’s five distinctive glass pavilions—through which passersby will be able to see the museum’s art—would now be located on the south side of the boulevard.

A model of Zumthor’s original plan for the building was displayed last spring as part of a LACMA exhibit intended to inspire public conversation about the project. But Topic No. 1 in that conversation quickly became Natural History Museum officials’ concern that the proposed structure could obstruct future scientific discoveries hidden in the rich subterranean world of micro-fossils.

In the face of such worries, officials of both museums appeared before the Board of Supervisors last September and pledged to work together to preserve the tar pits while creating a new building that would replace several aging structures on the LACMA campus.

The current design, which still must obtain a range of environmental and governmental approvals in order to go forward, grew out of that process.

“Necessity is the mother of invention,” said Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, who has directed county funding to a feasibility study of the project that is now underway. The new design “is actually more iconic than his original design. It’s a win-win.”

“We think the design is much better,” agreed Michael Govan, LACMA’s director and CEO. He said the new approach opens up more park space around the tar pits, creates better vistas on a “continuous veranda” around the building and makes a more compelling visual statement by bridging Wilshire.

“It really becomes a landmark,” Govan said.

Zumthor had originally intended the design to be a “love letter to the tar pits,” but as criticism emerged about its possible negative impact on science at the site, he “joked that the tar pits didn’t love it back,” Govan said.

Well, that loving feeling appears to have returned.

“I think the results show that we all worked in good faith to both provide LACMA with an exciting building and to protect and preserve the tar pits,” said NHM director and president Jane Pisano, who walked the site with Zumthor and her team of scientists in February. “It was a chance to really talk to the person who had the challenge of coming up with the solution. I have to say, I was just very impressed by what a good listener he is.”

Museum officials have previously said that it will take a $650 million campaign to bankroll all elements of creating the new building. An updated figure, taking into account a potentially more complicated construction process, will not be available until the feasibility study is completed in the spring.

Meanwhile, though, the collaboration between the two county museums already is paying dividends.

“I personally have had a lot of fun getting to know in more depth the science of the La Brea Tar Pits,” Govan said.

As for Pisano, she said she always felt a good solution eventually would emerge.

“One of the things that I knew for sure was that architects, particularly good architects, thrive when they’re given very difficult design challenges,” Pisano said. “And I think that both the thriving and the design challenges were present in this case.”

Posted 6/24/14

Magic in the muck

June 19, 2014

John Harris loves the smell of asphalt in the morning. As chief curator of the county’s Page Museum at the La Brea Tar Pits, he’s been enjoying the pungent smell since 1980. “I open the door of the car, and I’m here,” he said, demonstrating his appreciation with a dreamy sniff.

Not everyone shares his olfactory pleasure. “It sure smells,” observed a little boy in a baggy yellow T-shirt as he checked out some of the famous black ooze before heading into the museum with his family.

Individual noses notwithstanding, there’s a sweet smell of progress around the iconic tar pits these days. The famous mammoth and mastodon statues by the bubbling lake bed have been spiffed up and, more significantly, two scientific hot spots on the museum campus have been reactivated so that the public can get a sense of the discoveries being made each day right beside busy Wilshire Boulevard.

Beginning June 28, the mid-century Observation Pit—a repository for large Ice Age fossils from throughout the tar pit area—will become a highlight of the museum’s new Excavator Tour, after being closed since the mid-1990s. At the same time, Pit 91 is now open for excavation and public viewing after a seven-year hiatus.

The re-opened sites promise to be tourist attractions, educational resources and must-see stops on any fossil geek’s itinerary. They also mean new jobs. The museum has hired two new excavators for Pit 91. In addition, two new gallery interpreters will lead tours and five new guest relations staffers have been added.

Museum officials said the Observation Pit was closed for many years to allow excavators to concentrate their attention on the very productive Pit 91, site of such key finds as the first confirmed piece of a very young mammoth. But the excavation of Pit 91 eventually ceased because of another treasure trove of fossils uncovered in 2006 during construction of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s subterranean parking lot. Page Museum officials decided to focus excavation resources on the new finds, the most renowned of which was a mammoth nicknamed Zed. That ongoing effort is named Project 23 after the number of crates of specimens uncovered there.

Re-opening the Observation Pit and Pit 91 seemed like a good way to give visitors a different vantage point for exploring the museum’s collection, said Jane Pisano, president and director of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, which oversees the Page.

“We have a very exciting opportunity here to preserve the tar pits for present and future scientific discoveries and at the same time do a much better job for our visitors connecting the work outside with what’s on display inside the Page Museum,” Pisano said.

She added that the new exhibits offer a window into the latest scientific thinking on what fossils can teach us. The bottom line: size matters. Smaller is better for examining changes in the environment, including climate change. While it may be sexier to find a big cat or mastodon, “the reason to focus on the smaller fossils is that those critters lived here year round,” Pisano said. “We know the bison and larger animals were migrating and only came here once in a while.”

As chief curator Harris put it: “The real emphasis now is not on the big fossils, because we’ve learned pretty much what we can. Now it’s the smaller fossils and what they can tell us.”

Officials unveiled the new attractions today. Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky said it’s all part of a virtuous cycle of education and inspiration.

“The more access that people have to the tar pits, the more their curiosity gets piqued. The more their curiosity gets piqued, the better our quality of life is. And one or two of those kids who come here may become scientists who ultimately work for the Natural History Museum, analyzing what’s found underneath these properties,” Yaroslavsky said.

The reactivated exhibits at the tar pits are part of a Miracle Mile boom that includes extending the Purple Line subway and creating a new building at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, to be designed by renowned architect Peter Zumthor.

“This part of Los Angeles…is on a roll,” Yaroslavsky said. “We are very excited about the future as much as we are curious about the past.”

Yaroslavsky checks out some of the fossil excavation efforts taking place on the grounds of the tar pits.

Posted 6/19/14

Turning 50, to applause

April 3, 2014

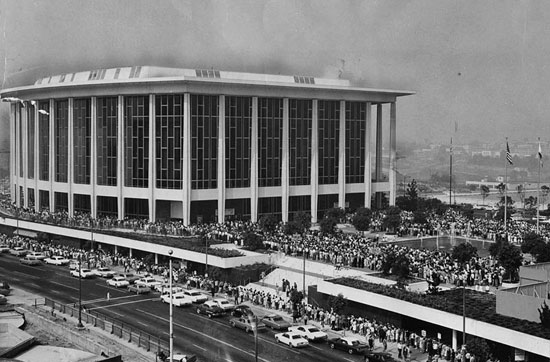

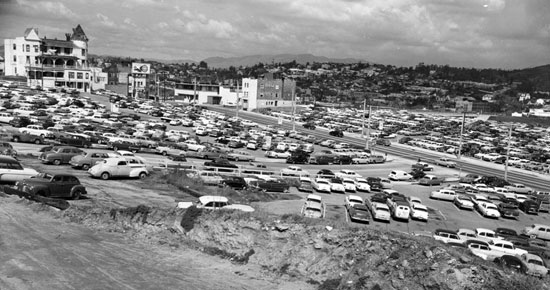

Within a year, the Music Center was a cultural fixture in L.A. Here, thousands of people line up for "Hello, Dolly" tickets. Photo/Herald Examiner

Like any grand dame, she avoids dwelling on birthdays. Still, a half-century is a milestone for a cultural icon in L.A.

So fans of the Los Angeles Music Center have gotten off to an early start in celebrating her upcoming 50-year mark. This week, a launch party on the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion stage kicked off a months-long celebration that will include some 60 large and small programs, including a gala on her December 6 golden anniversary and a public bash the next day on the Music Center Plaza.

“The Music Center has been critical to Los Angeles’ culture,” says Board Chair Lisa Specht. “We’re one of the top three performing arts centers in the country, along with Lincoln and Kennedy Centers, and for decades, we’ve been a hub of creativity.”

Not to mention a game-changer for L.A.’s metropolitan evolution.

“The Music Center was a major turning point in L.A. coming into its own in the postwar era as a major American city,” says Teresa Grimes, a Los Angeles historic preservation consultant who has documented the Center’s architectural heritage for past restoration projects.

Though the Los Angeles Philharmonic had been well established, it had no permanent home at the end of World War II other than the Hollywood Bowl, which was forced to close in 1951 due to a financial crisis, Grimes says. A series of “Save the Bowl” concerts, orchestrated by Dorothy Buffum Chandler, the wife of the Los Angeles Times’ publisher Norman Chandler, reopened the beleaguered band shell, but underscored the cultural shortcomings of the burgeoning city.

The winners of a Cadillac Eldorado, part of Dorothy Chandler's fundraising drive for Music Center construction.

Between 1951 and 1954, plans for a civic auditorium and convention center had been put on the local ballot three times, but never garnered the two-thirds majority it needed for passage. So in 1955, Chandler and the local Symphony Association began raising private funds for a hall to house the Philharmonic, which for years had been playing in leased space. As the highlight of their gala kickoff at the Ambassador Hotel, they raffled off a new Cadillac El Dorado.

“That was the beginning of it all,” Chandler is quoted as saying in Grimes’ Historic American Buildings Survey. “When we raised $400,000 in a few hours on El Dorado Night, I knew southern Californians wanted a music center badly enough to build it themselves.”

The effort took nearly a decade, at a time during which Downtown L.A. was being radically redeveloped. It required legislative approval and involved civic leaders from Donald Douglas to the Irvine family to Cecil B. De Mille.

Led by their arm-twisting society matron and her family newspaper, the Music Center boosters powered through social barriers dividing the Pasadena elite from Westside show business people, overcame pushback from provincial politicians, outlasted an economic downtown and triumphed in a last-minute squabble over whether the Center would be situated at First and Hope Streets, where the county wanted to put it, or at Chandler’s preferred location, the summit of Bunker Hill.

Chandler won, bumping the planned Department of Water and Power Building to the next block as the once-stately—and by now shabby—community of Bunker Hill was razed beyond recognition. She also brought on the architect of her choice, Welton Becket, who had worked with her on the Hollywood Bowl comeback and had master planned the campus of UCLA.

When Chandler decided during a visit to Europe that a single concert hall wouldn’t suffice, and that the new facility would do better financially if it also had a theater and a smaller forum, she won that battle also. Eventually, her tenacity in the project would put her on the cover of Time magazine.

The ultimate cost of the project was $33.5 million, with some $19 million of it from private contributions, including more than $2 million in small cash donations that local citizens dropped in so-called “Buck Bags” that were designed by Walt Disney and placed at cultural gatherings.

On December 6, 1964, the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion opened, resplendent with its crystal chandeliers and gold-leaf ceiling; the Mark Taper Forum and the Ahmanson Theatre were dedicated two years later. Opening night featured the renowned violinist Jascha Heifetz performing Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D Major, and the Los Angeles Philharmonic conducted by a 24-year-old Zubin Mehta.

In the ensuing years, everyone who is anyone has performed at the Music Center, from Ingrid Bergman and Nat King Cole to Neil Young and Ravi Shankar. Esa-Pekka Salonen and Simon Rattle made their American debuts at the Music Center, as did groundbreaking productions from “Angels in America” to “Zoot Suit.”

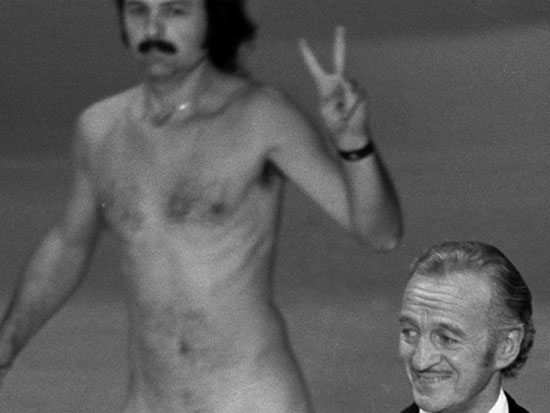

Between 1969 and 1999, most of the Academy Awards ceremonies were held there. The Dorothy Chandler Pavilion is where Sacheen Littlefeather refused Marlon Brando’s Oscar, where a naked man streaked onto national television behind David Niven and where Sally Fields exalted at being really liked by the Academy.

And countless Angelenos have memories of youthful jobs as Music Center ushers.

“I worked there as an usher during my senior year of high school,” recalls William Estrada, now curator and chair of the History Department at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. “It was the days of Zubin Mehta and we were required to wear these heavy, long Nehru-type jackets that were just awful to wear in the summer. Dorothy Chandler had her own parking space, and sometimes one of us was selected to walk her from her car to her seat.”

Today, Estrada notes, the Music Center, built on the site of the old Bunker Hill community, is just one cultural component in a downtown cityscape that is hardly recognizable compared to its pre-1960s, World War II incarnation. And it has expanded: The LA Phil is now housed at Disney Hall, the Center’s latest venue, and the L.A. Opera is at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion.

Nonetheless, some things change more than others: this week’s anniversary kickoff was sponsored by Cadillac.

Click here to buy tickets to anniversary events and to share your memories of the Music Center, and here to volunteer.

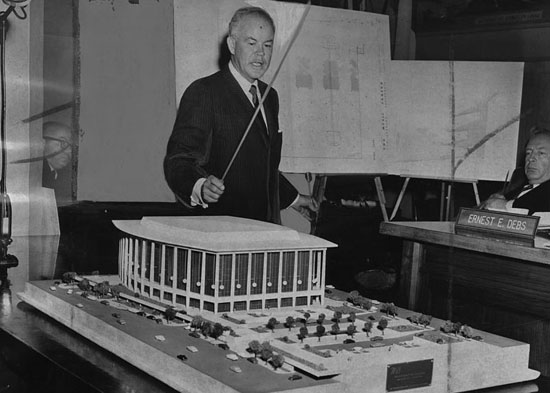

Architect Welton Becket presents plans for the new Music Center to the Board of Supervisors in 1960.

The Music Center was built as a public-nonprofit partnership on county land but was underwritten by private donations. Photo/Herald Examiner

The Mark Taper Forum went up in 1966, covered with a mural of precast terrazzo. Photo/Herald Examiner

Some memorable moments occurred during the Music Center's reign as the Oscar's home. In 1974, a streaker crashed the party and actor David Niven's presentation.

Posted 4/3/14

LACMA redesign to respect tar pits

September 26, 2013

Jane Pisano of the Natural History Museum addresses supervisors, as LACMA's Michael Govan, far left, and James Gilson of NHM look on.

Leaders of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Natural History Museum are pledging to work together to make sure that a proposed new signature building on the LACMA campus doesn’t harm the landmark La Brea Tar Pits.

Preliminary plans for the new art gallery, to be designed by Pritzker Prize-winning architect Peter Zumthor, were unveiled this summer as part of LACMA’s “Presence of Past” exhibition, which showcased the architect’s concepts for transforming the museum campus.

The Swiss architect’s proposal calls for a largely transparent gallery—allowing passersby to view art through glass even without entering the museum—built in a curving shape reminiscent of the tar pits on the site.

But concerns about those tar pits quickly bubbled up after an early model and design were put on public display.

Officials of the Natural History Museum and its Page Museum, which oversees the Pleistocene era fossil-rich tar pits as an active scientific research site as well as a public attraction, were worried about the impact of the proposed LACMA construction.

On Tuesday, leaders of LACMA and the Natural History Museum came together to inform the Board of Supervisors that they are committed to working together to make sure the tar pits are protected.

“We can guarantee that there will not be a significant impact on the La Brea Tar Pits as we develop the plan,” Michael Govan, LACMA’s director and CEO, told the supervisors. He added that the design, now in its “earliest stages,” is meant not only to improve LACMA but also to create better access to the Page Museum and the tar pits that share the Hancock Park site, which he said would end up with an additional 1.2 acres of ground space. A cantilevered section of the design over the tar pit lake bed already is being altered in response to concerns, Govan said.

Jane Pisano, the Natural History Museum’s president and director, noted that LACMA’s plan is still “very preliminary and fluid, and if there is a negative impact on the tar pits, the design can and will be adjusted to protect them. This is something that Michael has said many times, and we take him at his word.”

However, she added, there are challenges ahead.

“Preliminary review of the plans for the building indicate that it would severely impact six of the nine tar pits in the park,” she said.

“So, early days, we know we have a lot of work to do. But we are assured that it is early days,” Pisano said. She said the early collaboration is essential to ensure that this “world-renowned destination” and unique scientific resource isn’t harmed.

“Ice Age fossils and micro fauna trapped in the tar below the surface provide invaluable information about life thousands of years ago, as well as possible clues for climate change and habitat in the future,” Pisano said.

Both parties said they are continuing to work with the county’s Chief Executive Office in the coming weeks to develop a memorandum of understanding to help them chart the course ahead. If the project is approved by LACMA’s board of trustees, the museum would undertake a two-year feasibility study. Construction would not begin until sometime after a new motion picture museum opens on the campus in 2017.

Govan said that the project presents LACMA with a unique opportunity to be a leader in reimagining how an encyclopedic museum can be structured.

“It has a plan that will be more accessible to the public than I think any that’s been designed anywhere in the world to date,” he said. “And that’s one of the exciting opportunities of a museum in a park.”

Doing nothing is not an option, he added, given the deteriorating state of the four buildings that would be replaced by the new structure.

Just bringing those buildings up to code would cost $317 million, he said. Early construction cost estimates for the new building range from $400 million to $450 million—costs that would be offset by significant energy savings from the building’s solar panels and by an increase in visitors to the museum, he said.

Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky said that he was “not overly thrilled’ by the design at first, but has come to see it as a “stroke of genius.”

“This is a controversial plan architecturally. Any decent architectural plan is going to be controversial. If there’s no controversy, it isn’t worth the paper it’s written on.”

“Being able to build your project without doing any damage to the tar pits and the scientific research that continues to be done there is a no-brainer,” Yaroslavsky said. “There is room enough on that campus for both the tar pits and for the museum. And that’s the way it’s going to have to be.”

Architect Peter Zumthor's initial vision for LACMA shows a cantilever over tar pit lake bed. That element has since been altered. Photo/LACMA

Posted 9/25/13

L.A.’s biggest science project ever

June 13, 2013

Natural History Museum “citizen science” yielded the first L.A. sighting of this gecko species. Photo/Gary Nafis

When the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County launched its recent renovation, one of the goals was to make room for more science. Turns out it also made room for more scientists—of the backyard amateur variety, no lab coat required.

With the addition of the new Nature Lab and Nature Gardens as part of its centennial celebration, the museum’s growing involvement in so-called “citizen science” projects has gained new prominence, enlisting Southern Californians by the thousands in projects to catalogue the region’s biodiversity.

From insect counts to inventories of freeway roadkill, the museum has more than a dozen initiatives that are either ongoing or in the works now in which the public is playing a key role in the study of wildlife in Los Angeles County.

“It’s like crowdsourcing, and it can be an amazing resource,” says Lila Higgins, manager of citizen science and live animals at the museum.

Also known as participatory science, citizen science has become increasingly common as technology has made it easier for scientists, professional and amateur, to share observations and collaborate.

“In some ways, it isn’t new,” says Greg Pauly, curator of herpetology at the Natural History Museum, noting that volunteers at the NHM’s Page Museum have been helping process fossils for many years. “But with the Internet and smart phones and other digital devices, anyone can, say, photograph an organism and send it over the net to be included in scientific research. And people of all ages can help that way.”

Worldwide projects, such as the extraterrestrial life site SETI@Home, and the ornithology database eBird, have been reaching out to the public for more than a decade, and the Natural History Museum has been among the local pioneers of the concept. As far back as 1994, for instance, museum ornithologists enlisted the public in a study of feral parrots in Southern California.

The California Parrot Project, which is still ongoing, asked birdwatchers to let the study’s organizers know about local parrot sightings, and eventually yielded one of the first reliable counts of the numbers—upwards of a dozen species—of parrots breeding in the wild here, says Kimball L. Garrett, ornithology collections manager at the museum.

“It was extremely primitive—we’d mail out newsletters,” says Garrett. “But all this research from the mid-1990s gave us a baseline to figure out whether these populations are expanding or contracting now.”

Of the museum’s current batch of citizen science projects, the oldest is the 11-year-old Spider Survey, which asks the public to collect spiders in their homes and gardens, take down some data and bring or send what they find to the museum, Higgins says.

“At the time, it was the cutting-edge thing,” she remembers. “We launched it in 2002 at the museum’s Bug Fair, and the first week, a thousand spiders came in.”

Since then, some 6,000 spiders have been sent into the museum from throughout Los Angeles County; among the project’s findings was the first sighting of a brown widow spider in L.A.

“We’re a port city with people and goods coming and going on a daily basis, and with them, creatures sometimes hitch a ride,” Higgins explains.

Other citizen science projects have yielded even more exciting data. In 2010, Will and Reese Bernstein, a father and son from Porter Ranch, submitted a photo of a tiny reptile they’d seen at a backyard dinner party to the museum’s Lost Lizards of Los Angeles project. The critter turned out to be the first documented discovery of a Mediterranean House Gecko in L.A.

Although the non-native gecko (also known as Hemidactylus turcicus) has been spotted in the southeast United States, the L.A. sighting was so significant that the Herpetological Review plans to publish the finding this fall, says Pauly: “So Reese Bernstein, who is 12 years old now, will already have published a paper in a scientific journal.”

In April, the Lost Lizards project turned up yet another out-of-state reptile, an Indo-Pacific Gecko that was found in a backyard in Torrance. The project has been so successful, in fact, that it’s being expanded to include amphibians.

Greg Pauly’s Lost Lizards of Los Angeles project worked so well that it’s expanding. Photo/SoCal Wild

“Maybe you see a turtle at the park, or an alligator lizard in your yard, or maybe a salamander in the Santa Monica Mountains,” says Pauly. “You submit a photograph of it to our project, and that data will be available to scientists for generations to come.”

Coming up will be the citizen science component of Bioscan, a 3-year look at, among other things, the diversity of Los Angeles insects. Project Coordinator Dean Pentcheff is looking for a homeowners willing to host bug traps in their backyards and volunteers willing to sift through the take, sorting beetles from butterflies. A special side project in August will count bugs drawn to porchlights.

“We’re about three months in,” says Pentcheff, “and already we’ve found new species unknown to science.”

Pauly, the herpetologist, says such projects are especially important in places like Los Angeles County because the interface between the wilderness and the expanding urban landscape is on the cutting-edge of science these days.

“When you ask people here where they go to see nature, they say things like, ‘Sequoia’ or ‘Anza Borrego.’ But we’re surrounded by incredible diversity, and you don’t even have to leave L.A.”

Posted 6/13/13

Historic bash for Natural History Museum

May 30, 2013

An artist's rendering of the Natural History Museum's new entry, with a fin whale skeleton suspended above.

Los Angeles was a hard-partying hick town when top-hatted civic leaders opened its first museum, toasting it with water from the then-day-old Los Angeles Aqueduct. The fairground where the new landmark stood had been a nest of saloons and gamblers. L.A. was so culturally young that, for its first acquisition, the museum touted a goldfinch nest from the San Gabriel River bottom.

But a century can make such a difference.

On June 9, the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County will kick off its centennial with a day and night of hoopla in the rowdy ex-fairground that is now called Exposition Park. The festivities—with kid-friendly activities, food trucks, garden tours, live music, scientists and a nighttime concert by DEVO—will not only honor one of the nation’s largest and best-known natural history museums, but also will mark a milestone in the decade-long renovation and restoration.

The museum’s hallmark 65-foot fin whale will welcome guests from the top of a dramatic new glass entrance. Two Expo Line Metro stops will ferry visitors who prefer to arrive via L.A.’s burgeoning mass transit system.

A 3.5-acre Nature Garden will blossom outside a companion, state-of-the-art Nature Lab, where visitors can study wildlife, see it in action and then collaborate with science lovers region-wide in crowdsourced “citizen science” projects. Nearby, the museum’s acclaimed new Dinosaur Hall and award-winning Age of Mammals exhibits, both already opened, will be joined in July with the unveiling of the renovation’s final piece, “Becoming Los Angeles,” a permanent installation on the development of Southern California.

Meanwhile, visitors will be able to get a local history fix in the halls and rotunda of the 1913 building, which is on the National Register of Historic Places, and which has been restored and seismically strengthened.

“If you haven’t visited the Natural History Museum in a while, you should be prepared to find a vastly different institution,” says President and Director Jane Pisano. “This is a museum that has transformed itself.”

Pisano says the remodel arose from a change of philosophy at the museum.

“The old philosophy was very typical of natural history museums everywhere,” she says. “It was all about us—how we do research, how we take care of collections—and we changed that mission to focus on the visitor.”

The new aim, she says, is not to be “a book on a wall,” but to inspire wonder and a sense of discovery and responsibility in those who come to the museum. “We were doing a good job on wonder, but not so well on discovery and least well on inspiring a sense of responsibility for the natural world.”

Nor, she says, was the museum working as well as it could with Southern California’s natural landscape.

“There are very few cities that have the kind of climate we have,” she noted. So with the help of a new, county-funded garage that has consolidated parking, acres of paved land were transformed into wildlife habitat and gardens. Meanwhile, the building’s grand architecture was tweaked to create an easier flow between indoor and outdoor wonders.

Now visitors can take in the museum’s longstanding highlights—the dinosaur bones, the marine fossils—but also enjoy workshops led by master gardeners in the edible garden and unleash their kids in a “Get Dirty Zone.” The remodel also has set the stage for a long-term “citizen science” study of local biodiversity that museum experts expect to stretch throughout the Los Angeles Basin.

“This is a place where living things will come in and we can appreciate them in the wild,” says Karen Wise, the museum’s vice president of education and exhibits. “We don’t have to just have dead things on display.”

The new Natural History Museum isn’t the only cultural institution in Southern California to be reimagining the museum experience ways that are more authentic to L.A. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art under Director Michael Govan also has taken a more indoor-outdoor approach with installations such as Michael Heizer’s “Levitated Mass” and Chris Burden’s “Urban Light” on its campus. In fact, on the same day as the Natural History Museum celebration, LACMA will unveil a proposed architectural remodel that would make the county’s 50-year-old art museum literally transparent to visitors.

“I love letting the light in,” says Pisano. “I think it changes everything about the museum. I love that it’s fun, and I love that it has become a destination where visitors of all ages can come and spend the day and still not see it all.”

And, she says, there’ll be more to love as the next century gets underway at the museum. Pisano says the renovation has upgraded about 60 percent of the public space on the campus, with plenty of projects on the horizon.

“We need to redo the auditorium,” she says. “There still are exhibit galleries that need to be re-presented. We need to redo our Gem and Mineral Hall. We’ve talked about a Hall of the Americas for a long time.

“There’s a lot to be done,” says the museum director, “but I’m so optimistic about the future of this place.”

Posted 5/29/13

From museum gardener, seeds of change

April 4, 2013

Florence Nishida's Natural History Museum class has sprouted gardens all over L.A. Photo/Gordon Hendler

For some, spring is a chance to plant a few tomatoes. For Florence Nishida, it’s an opportunity to re-landscape the face of Greater L.A.

This month, for example, the 75-year-old master gardener will be checking in on some of the 20 or so South Los Angeles yards she helped turn into vegetable gardens. She’ll be sizing up a front lawn and a parkway for makeovers by Los Angeles Green Grounds, the urban gardening group she co-founded.

She’ll be monitoring the community garden she recently did in Koreatown for the new First 5 initiative, Little Green Fingers, and following up with the Los Angeles Conservation Corps on the raised beds she devised for outside their East L.A. office. Then there’s the LA Green Grounds table to set up and man for Earth Day at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, not to mention the regular Sunday gardening workshops she conducts at the museum.

And this is the former schoolteacher’s idea of retirement.

“From years and years ago, it has been my goal,” explains Nishida, “to have a vegetable garden and a fruit tree on every block in L.A.”

Nishida isn’t the only urban gardener on a mission these days in Los Angeles County, but lately, she has been among the more productive ones. Since 2010, when she persuaded the Natural History Museum to let her install a small teaching garden on its Exposition Park campus as part of an inner-city community project, her green thumb has been in many, if not most, of the urban gardening projects that have sprouted across the city like backyard zucchini.

One of her first students, artist Ron Finley, has won international acclaim with a pair of TED talks on urban gardening. Her former teaching assistant, the museum’s public programs manager Vanessa Vobis, is among at least five protégés who have gone on to become fellow master gardeners. Green Grounds, which she co-founded with Finley and Vobis, has literally broken new ground in South L.A., where the group has worked one yard at a time, installing gardens at volunteer “dig-ins” to help under-served neighborhoods grow their own organic produce.

Nishida herself has been called in increasingly to consult on community gardening projects throughout the county. Meanwhile, her edible garden at the Natural History Museum has drawn some 150 students just to the beginner’s workshop; this year, her class will expand to the new Erika J. Glazer Family Edible Garden, a showplace of fruit trees and seasonal plantings that will open officially in June with the rest of the museum’s new Nature Gardens.

“The museum was ground zero,” Nishida says now. “It all started from that class.”

Nishida hasn’t always seen gardening as a road to anyone’s revolution. A native Angeleno, she says, home gardens were a fact of life for her Japanese-American relatives throughout Southern California and in the Exposition Park neighborhood where she grew up.

“After World War II, my grandparents resettled in West L.A. near Sawtelle and grew vegetables in their front yard, as did a lot of people,” she remembers. But as time passed and L.A.’s economy shifted, fast food joints, un-walkable streets and dense apartments crowded out the kitchen gardens and mom-and-pop produce stands, gradually eroding the city’s health and turning organic produce into an upper-middle-class status symbol.

As Nishida moved to Topanga, worked and raised her four children, she says, she always held a notion that her old, blighted neighborhood might be restored if someone could bring back the green space. Eventually—after 20 years as an English teacher in the Los Angeles Unified School District, another 20 as a bureau manager and research librarian at People magazine’s West Coast Bureau and a graduate degree in botany that resulted in a sideline as a mushroom expert at the Natural History Museum—she decided to revisit her old theory.

“I had seen a little article in the Los Angeles Times about the master gardening program at the UC Cooperative Extension,” she remembers. “It was a tiny little article, but for whatever reason, I just saved it.” When she retired in 2008, she says, she took the classes, which require, among other things, that graduates go on to lead community gardening projects in under-served parts of their cities; one of her early projects was a home garden that later served as a model for Green Grounds. Another was a plan to bring gardening knowledge to Exposition Park by launching a class at the museum.

That idea—which dovetailed with the museum’s centennial plans to re-landscape its North Campus into a “living laboratory”—led to her meeting with Finley, an experienced gardener in his own right who had signed up for her class after he had noticed another master gardener’s project near Dorsey High School. Soon Nishida was asking Finley for advice on how to bring more neighborhood people into her museum classes.

“I told her, ‘They’re not gonna come to your classes—they got Burger King, they got Kentucky Fried Chicken’,” recalls Finley. “We gotta take it to them.” That, he says, was the start of Green Grounds, which effectively installs free gardens in people’s front yards in the style of an old-fashioned barn raising, and which has taken off since Finley’s second TED talk in February.

“We got people driving in from Ventura,” he marvels. “I’m like, damn! Is it that boring in Ventura? I mean, we had over 300 people sign up at our last dig-in, and all we needed was 15.”

Nishida says Green Grounds has been an education, not only in the art of managing volunteerism but on the laws of nature in L.A. Their first garden flourished for three months, only to be destroyed by the homeowner’s German shepherd. Another garden fed a family for nearly half a year before they were evicted. A third fell prey to a local gang she’d never heard of—gophers. Finley famously fought with the City of L.A. over the parkway he wanted to replant outside his house.

Nonetheless, Nishida says, 13 of the Green Grounds gardens are still blooming, with more in the pipeline; recently the group set up a fiscal sponsorship with the L.A. Community Garden Council to handle the influx of donations since Finley’s TED talks. And those gardens have, in turn, been change agents: Neighbors have gotten to know each other over samples of fresh produce, she says, and exercise groups have sprung up among dig-in volunteers and recipients of gardens.

In fact, she says, her only disappointments have been that the movement hasn’t spread faster, and that her commitments have left her so little time to tend to her own yard.

“Oh, it’s awful,” she confesses, laughing. “My vegetable beds are overrun with weeds.”

Posted 4/4/13

Calling all junior nature lovers

March 22, 2011

Will kids go wild for a machine that mimics the mouth of a pill bug? How durable should a soil sifter be if you want it to last for more than a field trip or two? Will people examine a compost pile without an invitation?

Inquiring minds at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County want to know.

In less than a month, the museum’s wildly popular Butterfly Pavilion will open for the spring and summer. In past years, the action has all been inside, in the fluttering realm of some 55 species of moths and butterflies.

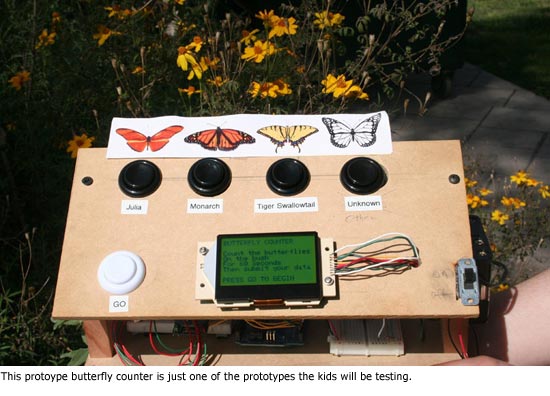

But this April 10 when the Pavilion opens, the creatures with wings won’t be the only ones under observation. In an effort to perfect displays planned for the new North Campus gardens that will open in 2013 at the museum, an assortment of prototype gadgets and interactive science exhibits will be tested throughout the summer in the outdoor space around the greenhouse-like structure.

And museum workers are looking to visitors, young and old, for help.

“We’ll be making observations on how people use these interactive exhibits,” says Lila Higgins, the museum’s manager of citizen science and live animals. “We’ll be talking to visitors, listening to their feedback.”

New displays will be set up, one or two at a time, to see how visitors use them and to pinpoint aspects that need tweaking. Pint-sized focus group (aka kids) are especially invited to weigh in.

Museum officials hope the new garden—part of a sweeping renovation that began last year with the “Age of Mammals” exhibition and that this summer will double the museum’s dinosaur exhibits with a new Dinosaur Hall—will teach visitors more about Southern California’s natural environment and give the museum experience a novel outdoor component. Proposed areas include a Home Garden with vegetables and fruit, an Urban Wilderness featuring many native California flora and fauna and a “Get Dirty Zone” where kids can, for example, play in a dirt pile.

Interactivity, however, is considered to be key, and museum staffers have spent months brainstorming ideas for displays, Higgins says.

“I personally love looking through compost piles and finding little beetles and grubs in there,” she says, “but will other people want to do that?

Ideas that have made it to the prototype stage include a butterfly counter, a periscope that will give children a birds-eye view of the landscape, a gizmo that will let kids sift soil and—dear to Higgins’ heart—a heart machine that will demonstrate how pill bugs break down leaves to help create compost.

“Everybody knows that worms aerate the soil, but not everyone knows what pill bugs do,” says Higgins. “So we were all around the table, with ideas flying around, and we knew we were going to have this Get Dirty Zone, and so we started talking about what pill bugs do. Well, they shred leaves. So what if a kid could have the chance to be like a pill bug? Maybe turn a crank and see that a pill bug’s mouth is like a leaf shredder?”

Within a few months, they had a prototype from Cinnabar California Inc, the Los Angeles firm that designed and built the Age of Mammals exhibit. Devised so that children as young as 5 can access it, it’s a metal mechanism in a wooden box that demonstrates the mechanics of the bug’s mouth.

“I don’t know if I’ve seen anything like it anywhere in the world,” says Higgins. “Maybe it’s a bit wacky, but the first time I saw the mock-up—well, when I see a kid use it, I’m going to be so excited.”

Posted 3/22/11

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink