Talking truth and power behind bars

August 22, 2012

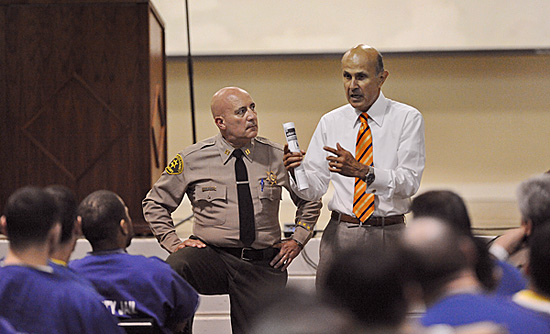

Sheriff Lee Baca, right, and Central Jail Captain Ralph Ornelas hold a "town hall meeting" with inmates.

Lee Baca is standing before a captive audience, sounding more like a preacher than the leader of the nation’s largest sheriff’s department.

“Start decorating your minds like you would a palace,” Baca implores a group of 90 inmates inside the archaic Men’s Central Jail. “Put positive things in there that will make you happy…I happen to believe you’re worth something.”

The men, seated shoulder-to-shoulder on metal pews in a jailhouse chapel, nod in agreement, giving the sheriff an appreciative hand to go along with their list of grievances. Earlier in the session, they’d complained to the boss about broken shower heads, uncomfortably cold air, inadequate “roof-time” recreation and deputies who, for seemingly no good reason, threaten to yank them out of the sheriff’s pet educational program.

Although the incarcerated men expressed gratitude for Baca’s appearance and assurances, the reaction to this “inmate town hall”—and the 173 others that have been convened during the past year—has been far less friendly among the sheriff’s other jail constituency: the deputies who work there.

Their union contends that the town halls have undermined the authority of deputies because inmates are being encouraged to, among other things, sidestep the chain of command, taking their complaints straight to higher-ups. The impact, according to union leaders: a potentially more dangerous workplace as frontline deputies lose the upper hand.

“They’ve never had the sheriff come in and say you can go talk to the captain,” Mark Divis, vice president of the Association of Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs, says of the inmates. “The word from the top is that you can go right past those guys [the deputies] and we’ll come running…At what level do you realize that you’re not dealing with a large number of rational individuals? If you’re in a church, it’s a bad place to talk about Satan worship.”

According to a union survey presented to the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence, 71% of 447 responding deputies said Baca’s town halls had made inmates feel more “empowered” and less respectful. Forty-nine percent said inmates actually had become more hostile toward their jailers.

Baca has dismissed the survey as not fully representative of the roughly 2,000 deputies who serve inside the county’s jails. Still, the findings do suggest a cultural divide that poses a significant challenge for the sheriff as he tries to fix a jail system rocked by allegations of deputy brutality and mismanagement. Among the rank-and-file, Baca’s self-described humanist views are not always embraced.

In police circles nationwide, Baca is known as a fervent reformer who believes in the power of innovative educational programs to transform the lives of inmates and end their cycle of recidivism. He has a doctorate from USC in public administration and says his “second love” is teaching, which he’s done at various levels for more than 30 years.

The inmates he visited last week were part of an educational program that focuses on positive decision-making and self-esteem development. The participants live together in a dorm, not in the packed, dank cells that have drawn most of the scrutiny over deputy conduct.

For that reason, their town hall meeting had a more upbeat tone than most, with some inmates thanking Baca for the opportunity to learn an assortment of life skills for the first time, from job training to anger management. As one told the sheriff: “I’m the kind of guy who ends up in Vegas with three hookers and married to one.”

Baca began the town hall meetings last October as the furor over alleged deputy brutality escalated. Saying his subordinates had failed to inform him of the problems, Baca ordered a series of management and policy changes that have helped reduce incidents of significant force. Baca also backed the creation of the blue-ribbon jail commission by the Board of Supervisors, encouraging current and former members of the department to come forward with testimony critical of top supervisors.

As of late last week, according to Men’s Central Jail Captain Ralph Ornelas, 6,870 inmates had voluntarily attended the town hall meetings, which run about 30 minutes and are led by captains. Baca himself has presided over only a few.

“I’ve learned to listen to what they say,” Ornelas says of the inmate meetings. “Sometimes it has validity. Sometimes they have a certain agenda against a particular deputy.” Whatever the case, Ornelas says, he believes the meetings are valuable because if inmates “see you as a person, then they’re less apt do to do something to you.”

The captain has statistics on his side. The numbers show that not only have use of force incidents declined, so too have inmate assaults on deputies.

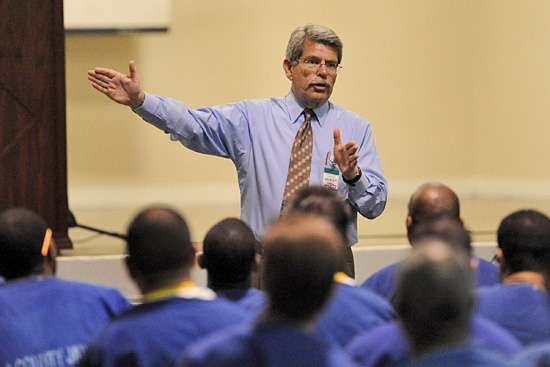

The jail commission’s general counsel, Richard Drooyan, says he sees the union’s resistance to the meetings as “a serious issue,” revealing the philosophical and managerial hurdles ahead for Baca.

“My view is that these meetings represent a positive development. They reduce tensions and that reduces violence,” Drooyan says, adding: “You change the culture by making sure supervisors are on board with your vision and that they tell their charges, ‘This is the way it’s going to be and if you don’t do it, you’ll be held accountable.”

Union leaders argue, however, that such views are better suited to the ivory tower than the central jail. The union’s executive director, Steve Remige, says many inmates simply won’t change their stripes no matter how much “the sheriff wants to teach them peace, love and freedom.”

Take, for example, the two inmates he says participated in Baca’s prized educational program, called MERIT—Maximizing Education Reaching Individual Transformation. “Just hours after graduating from MERIT,” Remige says, “they were caught trying to get some exposed metal under some ceiling tiles.” Remige says he assumes they were looking for materials to make jailhouse weapons.

Nonetheless, the problems in the jail have handed Baca a high-profile opportunity to showcase his reformer’s approach to incarceration. To that end, he invited Los Angeles County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky to observe last week’s town hall—and to say a few words at the end to the men participating in Baca’s educational program.

“The sheriff is trying to do something that is not conventional. On your shoulders rests the sustainability of this program,” the supervisor said. “He’s stuck his political reputation on the line by treating you like human beings…Don’t screw it up.”

Posted 8/16/12

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink