The Rock cometh—no, really

December 20, 2011

After months of postponements, the 340-ton boulder that the Los Angeles County Museum of Art has been awaiting since August has cleared what museum officials hope will be its final road blocks and is now scheduled to roll shortly after the first of the year.

After months of postponements, the 340-ton boulder that the Los Angeles County Museum of Art has been awaiting since August has cleared what museum officials hope will be its final road blocks and is now scheduled to roll shortly after the first of the year.

The route hasn’t changed, nor has the means of transit. But officials in the many municipalities through which the shrink-wrapped colossus will travel have at last all signed off on its passage, according to LACMA.

“Yes, it’s true,” laughs museum spokeswoman Miranda Carroll. “The permits are all secured now and all the cities have said okay. Everything is set.”

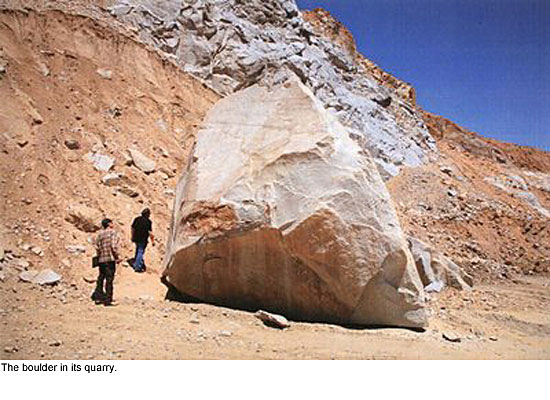

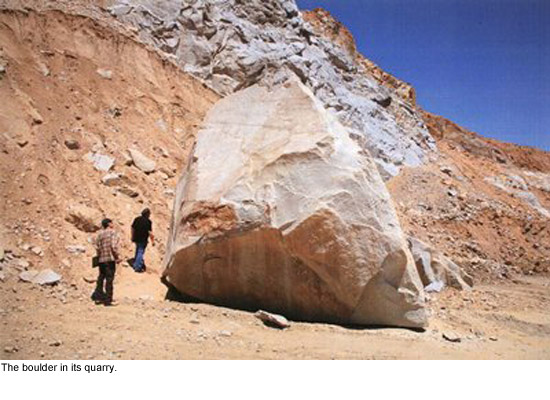

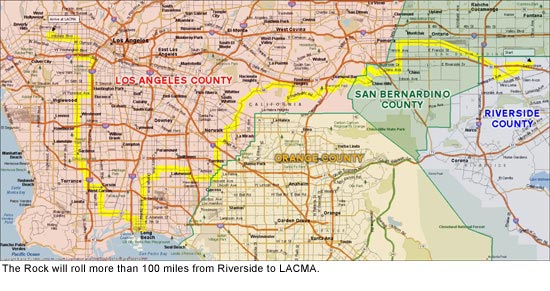

The boulder, destined to be the centerpiece in Michael Heizer’s massive new LACMA installation, has been waiting patiently at a Riverside quarry while officials in four counties tried to coordinate the bureaucratic details of its 100-mile move. The biggest snag involved the complexities of parking the rock on city streets during the daytime, when it will not be on the move.

Also complicating matters was that the transportation logistics turned out to be more complicated and time consuming than expected, forcing a process that normally takes more than a year into a span of six months. But with help from an assortment of players, including members of Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s and Supervisor Don Knabe’s offices, LACMA officials have set a date. Just forgive them if they aren’t ready yet to go public with it.

“We’ll be getting the message out before the holidays, so people know what’s happening, but we just want to be absolutely certain,” says Carroll.

Stay tuned.

Posted 12/8/11

Where’s The Rock?

October 13, 2011

For months, Los Angeles art fans have anticipated the arrival of the 340-ton boulder that will be the centerpiece of Michael Heizer’s massive new installation at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

The Rock, as its minders have come to call the massive hunk of granite, was supposed to roll to Los Angeles in August from the Riverside-area quarry where, since 2005, it has been patiently waiting. The slow-speed odyssey, on the bed of a special truck, is expected to be almost as epic as the artwork, when it is finally completed.

Now, after many false starts and much speculation, a route has been finalized (click here for a map) and The Rock has a new date of departure—October 25, according to LACMA Director of Communications Miranda Carroll and the company orchestrating the move, Portland-based Emmert International.

So what’s been the holdup?

“Well,” jokes Carroll, quoting LACMA associate vice president John Bowsher, “you can’t hurry art.”

The more detailed explanation is that it’s not easy to transport a hunk of stone the size of a 2-story granite teardrop along more than 100 miles of urban surface streets and through the bureaucracies of four counties and more than a half-dozen municipalities.

Just assembling the transporter has been time-consuming. Custom built to The Rock’s dimensions, the special 2-truck contraption, whose segmented design has been compared to a caterpillar, has had to be assembled at the quarry, where the mover’s crews have tested and retested it.

Emmert specializes in transporting buildings, transformers, satellites and other massive objects, but unlike a piece of equipment, The Rock cannot be cut into components or easily strapped down.

Its weight, combined with its transport system, will total 1,210,300 pounds, says Emmert’s director of operations, Mark Albrecht. And because it is not just a boulder but part of an artwork, it must arrive at LACMA intact—no chips, no scratches.

So part of the time has been consumed in arranging the transporter’s complex system of tires and axles so that The Rock is secure and the weight is spread safely. Albrecht says each axle line will carry about 49,000 pounds, less than the weight spread of a standard tractor-trailer, and The Rock will be nestled on a special sling atop them.

“The thing fell off a 400-foot cliff when they blasted it out of the quarry, so I don’t think we can hurt it,” jokes Albrecht. “But we’re still handling it with kid gloves.”

Albrecht says preventing the rock from taking out traffic signals and low-hanging wires has been a major undertaking. He and his crews have had to coordinate with nearly 100 utilities in multiple jurisdictions to lift power lines, remove trees and get other obstacles out of The Rock’s path as it moves.

“Verizon alone has six or seven different areas,” says Albrecht. “The cable companies each have a bunch. And they don’t group up very well.”

Timing also has ramped up the degree of difficulty, says Albrecht, noting that this move is actually considered a rush job in the heavy-haul industry. Glitches are inevitable; bureaucracies are slow. Already, he says, the route has been adjusted three times to avoid roads and bridges that turned out to be weaker than expected.

“When you’re moving something this big, you usually have a year or year and a half lead time to work the permits, but we were just awarded the project in April,” Albrecht says.

The most recent snag has been a hardy Los Angeles perennial—parking. The Rock can only travel slowly and at night. The trip will require eight daylong stops in eight jurisdictions. “The problem is, where do you park something that long and that big and that heavy?” asks LACMA’s Carroll.

Ordinary parking lots aren’t an option, Albrecht says; the transporter is so wide and low-slung that just getting in and out would take six hours. That, in turn, would wreck the down-to-the-minute coordination with utilities whose wires will be cleared and replaced as The Rock moves.

“The route we have can’t change,” Albrecht says, noting that various bridge and overpass constraints have now narrowed the path to a single option. And security is an issue—pulling over also raises the risk that vandals might get to the precious cargo.

So for all but one break (a gravel lot in Pomona that will be its first rest stop), The Rock must be parked somewhere wide, flat, accessible to vehicles, easy to guard and hard to get to for humans. In other words, Albrecht says, The Rock has to park in the middle of the road.

Four jurisdictions (Pomona, Rowland Heights, West Carson and the City of Los Angeles) gave the thumbs up to the one-day disruption in each spot. But Albrecht says local officials expressed reservations in the other four.

So this week’s challenge was persuading Chino Hills, La Mirada, Lakewood and Long Beach that rush hour traffic could be funneled around a boulder, a 20-foot-wide transporter, an 8- to 10-man CHP escort and a flag crew, says Albrecht:

“All we need is someone to say, ‘Okay, we’ll allow it this one time.’”

By Thursday, the cities were mostly on board, and Albrecht was optimistic that The Rock will make it to its designated spot on the North Lawn of the Resnick Pavilion in time for the installation’s scheduled November opening.

There, the boulder will be placed atop the 465-foot-long concrete trench that makes up the other half of the artwork. The half-built trench will be finished, and when the artwork, called Levitated Mass, is finally completed, viewers will be able to walk into the trench and pass under the boulder—an experience that will make The Rock appear to float.

The $5 million to $10 million cost of the project, including its transport, will be borne by corporate donors, such as Hanjin Shipping, and private donors, including a number of museum board members. The experience is expected to be extraordinary, when The Rock finally gets here.

Its estimated time of arrival is November 4, a few hours before sunrise. At least that’s the plan for now.

Posted 10/13/11

Updated 10/25/11:

Newton wasn’t kidding with that stuff about an object at rest wanting to stay put. The Rock’s moving date has been moved again.

Just when it seemed a firm date had been set for the boulder in Michael Heizer’s “Levitated Mass” to be moved from its Riverside quarry, those parking difficulties with the various cities on the route flared up again last week.

“We’ve pushed it back at least week for now,” says Mark Albrecht of Emmert International, the heavy haul transporter handling the move for LACMA. This week’s sticking points: Lakewood and Diamond Bar.

The cities are balking at having such a large load on their roadways, Albrecht says, but the only feasible route to the museum is the one that has already been worked out. He says the cities have no need to worry—the route is more than sturdy enough to handle the cargo, but the permitting is being negotiated in a fraction of the time it usually takes to plan a move this large and complicated.

Talks continue, with more meetings scheduled for this week. Here’s hoping that everyone involved sounds like the opposite of these trick-or-treaters by Halloween.

“The Rock” set to roll through L.A.

August 15, 2011

Later this summer, a 340-ton boulder will make its way from the Inland Empire to the middle of Los Angeles.

Recumbent on steel beams and a specialized 208-wheeled transporter, it will travel by night as the basin lies sleeping, a rough mass of California granite 21 feet wide and two stories tall. It will move on surface streets because it is too slow and huge for the freeway. At each dawn, it will halt; its entire 72-mile trip will take place at less than 10 mph.

From one end of the Southland to the other it will make its epic 9-day journey: down dark frontage roads beside the Pomona Freeway, past the twinkling lights of Ontario International Airport, along strip-malled boulevards in Diamond Bar and Walnut, through porch-lit subdivisions in Whittier and La Palma. Preliminary route maps take it past fast food joints in Compton, startling the night shift, and up through South L.A. by starlight, taking in the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum and the stately palms of the West Adams District.

Finally, The Rock, as its guardians have come to call it, will turn on Wilshire Boulevard, lit by the city and flanked by office buildings, and jog north on Fairfax Avenue for just a short distance. There, at last, it will find its elegant new setting—poised over a 456-foot-long, 15-foot-deep concrete trench as part of Michael Heizer’s Levitated/Slot Mass, an internationally anticipated installation at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

“It’s not like anything we’ve ever done,” says LACMA’s associate vice president for special art installation, John Bowsher, who is overseeing the boulder’s odyssey.

The artwork, scheduled to open to the public in November, will allow visitors to walk underneath the massive granite formation, down a slope that will create the illusion that the boulder is levitating. Assembled, the piece will be about as tall as the Resnick Pavilion, its neighbor on the LACMA campus.

But if Heizer’s work is expected to be a tour de force, so is its installation. LACMA director Michael Govan has called The Rock “one of the largest monolithic objects moved since ancient times.”

Orchestrating the rock’s move to LACMA from a Glen Avon quarry will be Emmert International, a Portland, Ore.,-based heavy-haul transporter.

Although Emmert and LACMA officials declined to discuss costs, officials at the quarry say they have been told the move, including fees, prep work and transport, will cost about $1.5 million. Emmert’s director of operations, Mark Albrecht, says the company’s fee is considerably less than that figure. The transport, like the artwork, is being financed with private donations.

Although Emmert and LACMA officials declined to discuss costs, officials at the quarry say they have been told the move, including fees, prep work and transport, will cost about $1.5 million. Emmert’s director of operations, Mark Albrecht, says the company’s fee is considerably less than that figure. The transport, like the artwork, is being financed with private donations.

Albrecht says a 15-man crew will accompany the boulder throughout the journey, along with various LACMA officials and police escorts. Though a tentative route has been mapped out, he says, the company is still in the process of acquiring state and local permits.

So far, the boulder is expected to travel uncovered (“No plans to shrink-wrap it, or anything like that,” he says, laughing). But like the route and the planned August 5 departure date, that could change as the deadline approaches. LACMA’s Bowsher says there’s been talk of boxing or partially covering the boulder because the artist is concerned that the spectacle of a 21½-foot-high hunk of granite riding like the Rose Queen through the streets of Los Angeles County will detract from the totality of the sculpture.

Heizer, who is famously private, could not be reached for comment. But Albrecht says the artist “has been involved for the whole process,” cautioning them via LACMA to “make sure the rock isn’t scratched or etched, make sure it’s carefully handled, make sure you don’t leave any big marks on it.”

Damaging it would seem to be the least of anyone’s worries, considering that the boulder was blasted in 2005 from the face of a quarry in the Jurupa Mountains and survived intact.

“Came right from the crown of the mountain,” marveled Dan Johnston, then-project manager for Paul J. Hubbs Construction, which owned the quarry. “Blast brought it down and it landed right in the middle of soft dirt.”

Johnston, now retired, says that as soon as he saw it he called Heizer, a geologist’s grandson known for massively scaled artworks, including Double Negative, a 1,500-foot trench cut into the side of a desert mesa.

“Michael had bought some large rocks from us before, in 2004 and 2005, for other projects,” Johnston says. “He wanted granite, and the thing about granite is that not a whole lot of places have it. Riverside granite is like Portland cement—if you know about rock, it’s something you look for. And he had come to us looking for large rocks.

“Well, that was one good-lookin’ rock…Way it was shaped, I knew he’d love it. And he did, he fell in love.”

Stephen Vander Hart, co-owner of Stone Valley Materials Inc., which now owns the quarry, says he had heard that the artist paid $120,000 for the boulder. But Johnston, while refusing to divulge the actual price, says “it was nowhere near that much.”

Vander Hart says the quarry’s crews had been working around the rock for years when his company took over in 2010, and its safekeeping was a condition of the buyout.

“We’ve had to work hard to not bump into it,” he says. “Most of the guys here are just regular equipment operators, blue collar guys, love their wife and kids, and they’re just like, ‘Get it the hell outta here, let me do my job. They’re not that into art.”

But the quarry boss says he, for one, was touched when he heard LACMA Director Govan talk about the artwork and how it came to be.

“He talked about how 400 years from now, people would ask, ‘How did this group of people move something this size? What was their motivation?’ California is all strip malls and franchises. Everything is brand new, at least here in the Inland Empire. We bury our history. But this is something that will be there for a long, long time.”

Posted 6/29/11

Updated 8/16/11: The groundwork is taking a little bit longer than expected, but officials at LACMA say the rock is expected to roll shortly after Labor Day.

“There were some permitting issues for the route from the quarry, ” says Miranda Carroll, LACMA’s director of communications. The tentative start date now is September 6, with an arrival at the museum on September 14 or 15, she says.

The 340-ton boulder is a key element in a much-anticipated installation by the reclusive earth-art master Michael Heizer. Museum officials had hoped to move the 340-ton boulder from its Riverside-area quarry this month.

In any case, Carroll added, “there won’t be a big hoo-hah because we’ll be moving it in the middle of the night.”

A night, and more, at the museum

June 29, 2011

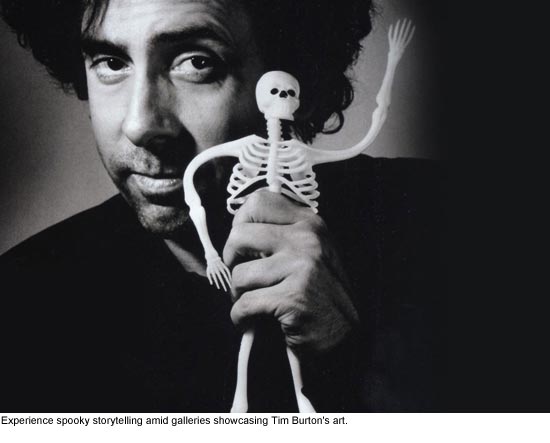

No Ben Stiller. No rampaging dinosaur skeletons. No Egyptian curses.

Better.

Starting Friday, you can experience not one, but five nights at the museum—the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, that is. Families can gather ‘round the flashlight every Friday evening at 7 p.m. throughout the month of July for some spooky but safely kid-friendly nighttime storytelling, set amid the galleries currently featuring the sculpture and artwork of filmmaker Tim Burton.

The fun begins this week on Friday, July 1, with the program “Tales with a Twist,” featuring storyteller Karen Golden sharing creation myths and other mysteries of nature.

Upcoming events will take you traveling with ghosts and offer tales of spiders, bears and other creepy critters. Here is the complete list of programs.

The Tim Burton exhibit is located on the ground floor of BCAM, LACMA’s big red gallery. Tickets are included with general admission, but they’ll only be available an hour before the event, and seating is limited.

Here’s everything you need to plan your visit.

Posted 6/29/11

Curtain call for Hollywood costumes

January 26, 2011

Like many stars of a certain age, they no longer get out much. Still, as Oscar season approaches, they deserve their due. Some made history with Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin. Some were themselves Academy Award-winners.

True, most have spent the past several years in a vault in the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. But the 250 or so historic movie costumes—owned, improbably, by Los Angeles County—represent one of the most well preserved aggregations of stardom in Hollywood.

“The bulk of people don’t know about it, but it’s a very important collection,” says Glenn Brown, archivist at the MGM Corporate Archives. “Its pieces are from some of the earliest days of film, things from the ‘20s and ’30s, donated by the stars themselves. Things you hardly ever find anywhere.”

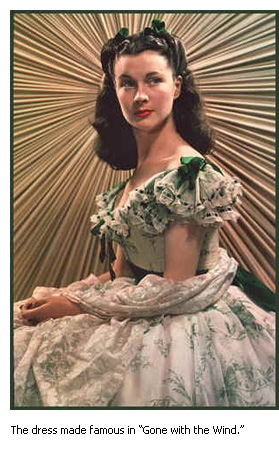

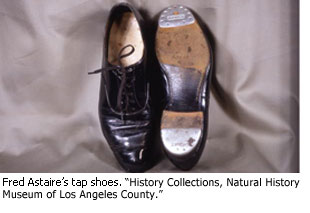

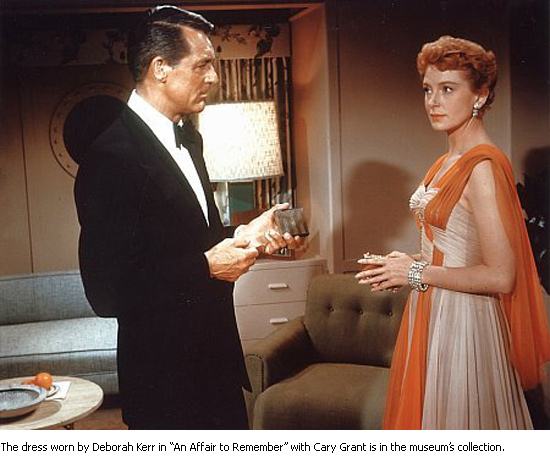

Chaplin’s “Tramp” costume is there. So are Fred Astaire’s tap shoes, Charlton Heston’s “Ben Hur” tunic and the green-sprigged dress (battered but unbowed) that Scarlett O’Hara wore in “Gone With The Wind” at the barbecue at Twelve Oaks. There’s also the pink Howard Greer ball gown that Pickford wore in her first talkie, “Coquette.”

The Natural History Museum has amassed not only many of the most important costumes from the earliest days of the movies, but also a trove of historic film props and other movie mementos, from Lon Chaney’s makeup kit to preserved locks of Pickford’s golden hair, lopped off when she famously bobbed it. Back in the day, such items were considered so insignificant that studios routinely burned, tossed or reused them.

Beth Werling, who manages the collection along with a wide range of three-dimensional artifacts for the museum, says it’s “the biggest collection of its kind in a public institution.” That “public” qualifier is important, historians say, because in recent decades, Hollywood memorabilia has become increasingly privatized at institutions like the Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising and in individual collections, such as one owned by actress Debbie Reynolds.

“Things are everywhere,” says Shelly Foote, a longtime historian in the Smithsonian Institutions’ costume collection. The county’s collection is essential for pieces from the ‘20s and ‘30s, says Foote, who turned to the Natural History Museum in researching her forthcoming book on the designer Greer.

Of course, a public institution best known for dinosaurs and rock collections might be the last place most people would go digging for Hollywood glamour.

“But when the Natural History Museum was founded in 1913,” says curator Werling, “it was called the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science and Art. So we’ve collected Los Angeles history since the very beginning.”

The movie collection began in 1930, she says, after studios and stars in the nascent industry began donating items—some just to get rid of them, others because prescient museum officials felt they might be of historical significance someday.

“The then-curator simply contacted everyone and anyone in the industry at the time and asked for donations,” says Werling. Typically, she and others say, such requests elicited shrugs and amusement.

“Costumes were a means to an end,” explains Deborah Landis, director of the David C. Copley Center for Costume Design at UCLA. “The movie was all that mattered. Just as sets are broken up and props go back to the prop house, costumes were reused and re-dyed, and the hems were cut and remade, and nothing was kept because nothing was valued.”

Werling credits that benign disregard for the museum’s unparalleled cache of Chaplin memorabilia, donated for the most part by the actor himself.

“He was a very, shall we say, cautious individual when it came to money and I don’t think he would have ever given anything away if he had any idea what these items would later be worth,” says Werling.

“But the motion picture industry was only about 25 years old then, and it was the beginning of the studio era. It was still being argued whether it was even an art form. And I think people were just flattered to think that anyone saw what they were doing as something worth saving.”

As a result, the county’s collection ranges from the roller skates Chaplin wore in “Modern Times” to his burlap boots from “Gold Rush.” “He donated his Tramp costume from ‘City Lights’ and, as a result, we have the only complete one in still in existence,” Werling says.

Since then, she says, items have come from a variety of sources. Carl Laemmle, who founded Universal, donated a number of early items. A more recent cache came from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art after curators there refocused their costume collection more on couture and fashion. Still others were donated by collectors who decided their items deserved museum-level care.

A motion picture costume is more than just clothing, says veteran costume designer Jeffrey Kurland, who designed the costumes from last year’s sci-fi thriller, “Inception”.

“It’s character-driven. It helps build a visual picture of a character,” he says. “Think of Scarlett O’Hara in ‘Gone With The Wind’ in that barbecue dress, that garden print, so young and frivolous and puffy. That’s how we meet her. And then watch the progression as war comes and her character changes.

“The clothes become slimmer and tighter, until there she is toward the end, in that garnet red dress with Rhett Butler. Think of the line, the fit, the silhouette. Look where she has finally traveled. The clothes show her character’s arc.”

“The clothes become slimmer and tighter, until there she is toward the end, in that garnet red dress with Rhett Butler. Think of the line, the fit, the silhouette. Look where she has finally traveled. The clothes show her character’s arc.”

Local museum-goers have seen little in recent years of the county’s collection, partly because of space constraints and partly because of the fragility of the costumes themselves. The barbecue dress from “Gone With The Wind”, for example—which came to the museum from LACMA—is undergoing extensive repair work because time has all but shattered the costume’s lining, says Werling.

But mostly the collection has remained backstage because of an ongoing rebuilding and transformation project leading up to the Natural History Museum’s 2013 Centennial. So far, the initiative has restored and seismically retrofitted the Beaux Arts museum building and added the new “Age of Mammals” exhibit. But construction has closed the small area where the costumes used to be shown, a few at a time, in glass cases.

A new California history hall is expected in late 2012, just before the museum’s centennial celebration. When it opens, the public can expect to see a lot more of Hollywood, says Werling. Until then, the public’s best hope is to look for the items that are frequently placed on loan to other exhibitions.

Or look for events like the one set for February 4-5 at William S. Hart Park in Newhall—a “ChaplinFest” celebrating the 75th anniversary of “Modern Times,” whose closing scene, with its poignant rendition of the song “Smile,” was filmed nearby on the Sierra Highway.

It was one of Chaplin’s most important films, depicting the tragicomic breakdown of a factory worker beset by the dehumanization of the industrial era. At one point, in fact, the Tramp is swallowed up by the giant gears of the assembly line and run through the machine in his striped workman’s outfit.

On display at Hart Park will be those iconic overalls Chaplin wore—ready for their close-up, even now.

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink