The last map standing

September 28, 2011

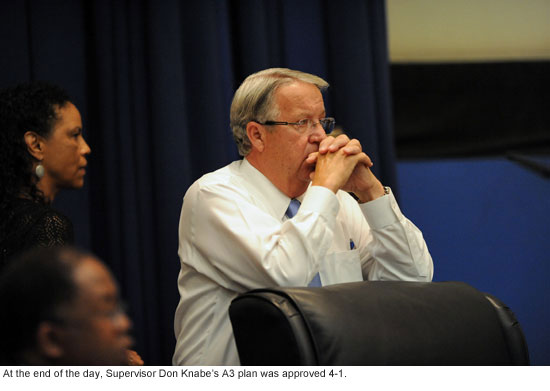

After weeks of robust debate that sparked thousands of letters, e-mails and public comments, Los Angeles County’s most contentious redistricting process in a generation came to a dramatic close Tuesday as supervisors voted 4-1 to approve new political boundaries that hew relatively closely to the current map.

After weeks of robust debate that sparked thousands of letters, e-mails and public comments, Los Angeles County’s most contentious redistricting process in a generation came to a dramatic close Tuesday as supervisors voted 4-1 to approve new political boundaries that hew relatively closely to the current map.

The supervisors voted after hearing six hours of public testimony from 243 speakers who invoked the history of Latinos in L.A., the meaning of changing demographics and sharply divergent opinions on whether “racially polarized voting” still exists in the county to such an extent that it denies Latinos an equal opportunity to elect a person of their choosing. Others asked supervisors to preserve existing “communities of interest” so that neighborhood priorities such as protecting the environment and building health care networks would not be jeopardized.

In approving the redistricting map known as A3, supervisors rejected competing proposals by Supervisors Gloria Molina and Mark Ridley-Thomas that had sought to create a second supervisorial district in which Latinos make up a majority of the citizen voting age population.

In an initial round of voting toward the end of Tuesday’s meeting, it became clear that none of the proposed maps would receive the 4-1 “supermajority” vote needed to pass. So, after a brief closed session and some minor amendments to the A3 plan offered by Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich, Ridley-Thomas signaled he would change his vote.

“There is a rather obvious lack of consensus on a map here today,” Ridley-Thomas said. With a possible legal challenge from the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund looming, he said he wanted to avoid a “potentially divisive delay” and to push the matter toward the “closure” of a federal court ruling on what the Voting Rights Act required.

While he said he still believed in the plans he and Molina had put forward, he said he wanted to avert “the unnecessary gamble of the uncertainty of an untested appeal process”—a reference to the special redistricting commission made up of the District Attorney, Assessor and Sheriff that would have stepped in to decide the matter if the five-member Board of Supervisors had been unable to muster four votes for any of the proposals. After Ridley-Thomas’ change of course, the board voted 4-1 in favor of the A3 plan, with Molina casting the dissenting vote.

Ridley-Thomas’ S2 map and Molina’s T1 proposal would have moved up to 3.5 million residents to new electoral homes and split the San Fernando Valley into three supervisorial districts instead of the current two. The plans drew strong reactions across the county, and were criticized as blatant gerrymandering by Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky and others.

Knabe, in remarks before the vote, said that his A3 plan was the best way to ensure all groups in the county are well-represented. More radical boundary changes, he said, weren’t legally necessary and don’t reflect modern-day electoral realities.

“We cannot hold onto the past when we see clear illustrations of change with the election of minority candidates at every level of government,” Knabe said. “Hanging onto the legal battles of 20 years ago does nothing to move us forward…At the end of the day our job, as elected officials, is to represent all ethnicities, all people in Los Angeles County.”

Molina, however, in a presentation before the vote, contended that creating a second “meaningful Latino opportunity district” was required under the federal Voting Rights Act because of current demographics and a long history of bias.

“The legacy of Latino political exclusion and discrimination in L.A. County is so pervasive,” she said, “that it has affected not only the way Latinos and Latino candidates are perceived by non-Latinos but the way Latinos perceive their own ability to participate in the political process.”

Map A3, she said, waters down the voting strength of Latinos by creating a large Latino majority only in her 1st District while keeping their numbers to a third, or lower, in the other four districts. Latinos make up nearly 48% of the population countywide, and about a third of the county’s citizens of voting age.

Yaroslavsky kept his remarks brief, saying he had already written or said just about everything he needed to on the issue. But he thanked the community for what he called “this unprecedented turnout” and for the level of discourse throughout the process. “On the whole it was an elevated public testimony that we heard and it contributed to the public understanding … of what’s before us,” he said.

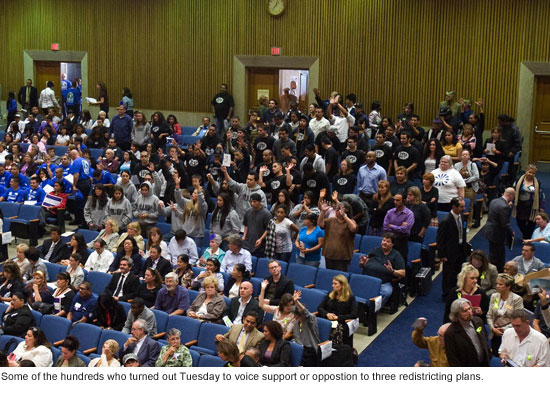

More than 900 people turned out for the meeting, arriving in the early morning, filling the board hearing room and spilling into three overflow rooms and a large white tent erected on the Hall of Administration lawn.

But by the time the final vote was taken just after 6 p.m., only a handful of spectators remained to witness the moment—the culmination of the once-every-decade process in which boundaries are redrawn to reflect U.S. Census data. (Click here for our story on the day-long civics lesson for hundreds of students who attended the meeting.)

The new district boundaries take effect in 30 days. Here are some of the changes in store forLos Angeles County under the plan:

More than 277,000 people will move to new districts, and several communities will get a new supervisor. Claremont, for instance, will move from the 5th District to the 1st. Santa Fe Springs will move from the 1st to the 4th.

Several other communities, now split between two supervisors, will be consolidated. The lake area of Silverlake will no longer be in the 3rd District, for instance; instead, the whole community will be drawn into the 1st District, as will all of Pico Rivera, Azusa and West Covina. Similarly, the 2nd District will encompass all of Hawthorne and all of Florence/Firestone, and the 4th District will include all of South Whittier and West Whittier/Nietos.

The San Fernando Valley will continue to make up more than 50% of the 3rd District’s electorate, and the 3rd District also will continue to represent the Westside, Hollywood and the Santa Monica Mountains. The 3rd District will lose 15,468 people, creating a district that is 45.8% white, 37.9% Latino, 11.1% Asian/Pacific Islander and 4% African American.

The population of voting-aged Latino citizens will fall in the 1st District from 63.3% of the electorate to 59.7%. In the 4th District, it will rise slightly from 31.6% of the electorate to 32.8%.

Asian Pacific Islanders, who had expressed concerns that redistricting would dilute their representation, will continue to be concentrated in the 1st, 4th and 5th Districts, with the highest concentration of voting-aged API citizens in the 1st District at 19%.

Population also will be more evenly distributed among the districts under the plan adopted Tuesday. Prior to A3’s approval, the largest district, the 5th, had 2,088,786 people, while the smallest, the 1st, had 1,893,001. That deviation, about 10%, will be reduced under the new plan to 1.57%.

Posted 9/27/11

Redistricting’s silver lining

September 27, 2011

In my many years of public life, never have I seen the kind of massive and spirited civic engagement that has unfolded during these past few weeks of Los Angeles County’s redistricting efforts. On Tuesday, overflow crowds once again converged on the Hall of Administration as the Board of Supervisors, on a 4-1 vote, approved new boundary lines for the five supervisorial districts.

In my many years of public life, never have I seen the kind of massive and spirited civic engagement that has unfolded during these past few weeks of Los Angeles County’s redistricting efforts. On Tuesday, overflow crowds once again converged on the Hall of Administration as the Board of Supervisors, on a 4-1 vote, approved new boundary lines for the five supervisorial districts.

The approved plan, while not perfect, is far better for residents throughout Los Angeles County than the two proposed alternatives. It keeps together communities of shared geographic, economic and environmental interests (to name a few), while remaining fully compliant with the federal Voting Rights Act, which protects the crucial electoral interests of minority groups.

To be sure, the process that culminated in Tuesday’s historic vote was punctuated with strong words and heated emotions. But there was something encouraging about it all, no matter what your views or loyalties. From one end of the county to the other, from its urban core to its rural reaches, people were engaged, writing thousands of letters and appearing en masse to express their diverse opinions on representative democracy in their communities.

The debate forced us to assess—and rally behind—the things that are most important to us in this complicated region of competing interests and values. We may not always have liked what we heard, but I had the sense that, at least, we were listening and learning. Consider this: despite the passionate feelings on all sides, I can’t recall a single speaker of the hundreds who testified who was shouted down or disrespected.

As we move forward, I know this issue could continue to generate controversy with potential litigation. But I do believe it’s important at times like these to reflect on those things that we, as a broader community, can take pride in. I’d like to thank all of you who participated in our deliberations and demonstrated your commitment to our collective future.

Posted 9/27/11

A hearing—and a civics lesson, too

September 27, 2011

Hilda Placencia got a lesson in the complexities of political representation. Jesse Almaraz learned that government isn’t necessarily dull. Christopher Trujillo discovered that, when it comes to civic engagement, it helps to be a morning person.

Hilda Placencia got a lesson in the complexities of political representation. Jesse Almaraz learned that government isn’t necessarily dull. Christopher Trujillo discovered that, when it comes to civic engagement, it helps to be a morning person.

“We were the first ones into the building,” the 18-year-old El Monte student noted, planting himself in a choice seat in the Kenneth Hahn Hall of Administration. “But we had to be ready to go at 5:45 a.m.”

Tuesday’s public hearing on redistricting was many things to many people—a referendum on social justice, a call for a geographic balance of power, a refresher course on Los Angeles County’s shifting demography.

But for hundreds of adolescents packed into the audience—some bused in by community organizers, some carpooled in with their high school teachers—the marathon meeting was a daylong civics lesson.

“My teacher explained it to us, but this is explaining it better,” said Placencia, a 16-year-old senior (“Class of 2012!”) who was part of a contingent from Schurr High School in Montebello. “I learned more today here at this meeting than I did all day yesterday.”

More than 900 people showed up in the early morning to applaud, testify and otherwise weigh in on three rival plans for redrawing the county’s supervisorial boundaries. By the time the Board of Supervisors voted to adopt an amended version of plan A3, which mostly follows the current boundaries, it was dinner time.

But one of the most striking aspects of the crowd was its youth.

One section was packed with row upon row of students bused in from job training programs in Supervisor Don Knabe’s Fourth District. Another was filled with 50 blue-shirted teenagers and young adults who came from the San Gabriel Valley Conservation Corps in Supervisor Gloria Molina’s First District in a convoy of vans.

A classroom of students from Bell Gardens High School, escorted by Molina staff members, shuttled in and out, politely observing until mid-afternoon, when their school day ended; later, the supervisor—whose own Latino-majority district had been created as the result of a redistricting lawsuit—clambered onto a Roosevelt High School bus to thank still more young people for coming.

Teenagers being teenagers, of course, few could name their supervisors—a problem that afflicts some adults as well. But that didn’t dampen their interest. At one point, Placencia and a group of friends from Schurr High found themselves in a tutorial on how redistricting can affect environmental policies as well as ethnic power—a conversation that started when they found themselves seated next to Rosie Dagit, senior conservation biologist with the Resource Conservation District of the Santa Monica Mountains.

At Dagit’s suggestion, the students began examining wall maps delineating the proposals. Soon they were talking to Topanga environmentalist Ken Wheeland, who was sitting nearby. They listened attentively as Wheeland—his denim work shirt decorated with a small sage-green ribbon to demonstrate his concern for mountain preservation—explained that he feared the environment would take a backseat to commercial interests if the mountains were placed in the same district as the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.

As their conversation wound down, Wheeland also shared some adult political perspective, saying that no matter what map won, “there’ll probably be a lawsuit and a judge will decide.”

The students then returned to their seats, periodically peppering Wheeland’s fellow environmentalist, Dagit, with questions as the surrounding crowd waved signs for the redistricting plan backed by Molina.

“I told them, ‘I’m not here to tell you what to think—you should make your own decisions, think about what’s important to you, look at the maps, listen to the testimony’,” Dagit reported. “About halfway through, three of them asked us for green ribbons.”

Elsewhere in the audience, 18-year-old art student Jesse Almaraz of Long Beach sketched as he listened to the proceedings. A student at Urban Arts Crew, a South Bay job training program supported by Knabe, Almaraz said he wanted his supervisor to remain the same.

“If our district were to change,” he said, “we might lose our funding. I’m all for equal representation or whatever, but I don’t feel that only Latinos can represent Latinos.”

What surprised him and his friends most, he said, was the vigor with which all the groups defended their positions.

“I thought this would be kind of a quiet thing but people keep making noise and shaking signs,” he marveled. “I wish we had some signs, man. That would be cool.”

Across the aisle,Trujillo and the Conservation Corps contingent stayed almost to the end of the proceedings.

“It’s a lot of information,” the teenager said. “But I’m learning a lot about what’s fair and what’s not fair. Some of it sounds right and some sound wrong, but I’m just gonna support Molina. I’m listening so I can prepare for the next time this comes around.”

And one bit of preparation he’d repeat, he said, was fortification for a long siege.

“Burritos and fruit snacks,” he recommended. “Stayin’ strong.”

Posted 9/27/11

It’s officially “Pacific Standard Time”

September 26, 2011

Pacific Standard Time starts this week in earnest, examining L.A.’s role in the postwar arts scene in venues as vaunted as the Getty Center and as modest as a Westside school for the arts.

Pacific Standard Time starts this week in earnest, examining L.A.’s role in the postwar arts scene in venues as vaunted as the Getty Center and as modest as a Westside school for the arts.

Although choice sneak previews have been open for a few weeks at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and at smaller museums, this weekend marks the official opening of the massive arts initiative centered on Southern California. Whether you love art or just love L.A., the range of shows opening this week should, like the city itself, have a little something for everyone.

Highlights include the first major study of modern California design at LACMA, with an accompanying side exhibition at the A+D Architecture and Design Museum honing in on the work and philosophy of Charles and Ray Eames. The LACMA show, California Design, 1930-1965: “Living in a Modern Way,” will start with the origins of California modernism in the 1930s and include, along with important work by Richard Neutra and Rudolph Schindler, a vintage Airstream Clipper and a reconstruction of the Eames’ living room, which was dismantled piece by piece and moved to the museum from the Eames House in Pacific Palisades.

Another must-see show will be at the Getty Center, where Pacific Standard Time: Crosscurrents in L.A. Paintings and Sculpture will look at those two art forms in Southern California from the 1940s until the 1970s. The exhibition, featuring some 50 important L.A. artists, is in some ways the ground zero for the Pacific Standard Time initiative, which was launched as a joint initiative of the Getty Research Institute and the Getty Foundation.

The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles will also be in on the PST action, with a show that highlights its role as the city’s contemporary art venue before its art exhibitions were moved to LACMA in the mid-1960s. Among the featured artists will be John Baldessari, Ed Moses, Robert Irwin and Ed Ruscha.

The Hammer Museum will examine L.A.’s African American visual artists, ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives will look at the gay and lesbian art scene here and a show at MOCA’s Geffen Contemporary will show how L.A. art reflected the foment of the Vietnam War and the Watergate Era.

Meanwhile, a small show at the Sam Francis Gallery at the Crossroads School will explore the role of women art dealers in L.A. in the 1960s and 1970s.

And that’s only a taste of PST’s opening week of shows, talks and happenings. For a more complete calendar, click here, and for information on the initiative, click here.

Posted 9/26/11

Deadly force by deputies targeted [updated]

September 26, 2011

A study released Thursday takes aim at shootings by deputies in the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, concluding that Latinos and blacks are shot in disproportionately higher numbers when compared to their arrest rates and that an unusually large number of unarmed individuals were fired upon last year.

In his 30th semi-annual report to the Board of Supervisors, Special Counsel Merrick Bobb also expressed “deep concerns” about the consistently high numbers of shootings in the department’s Century Station, where a large percentage of deputies have been involved in multiple shootings and where many, he says, have fallen behind in the department’s mandated training.

Moreover, Bobb was sharply critical of the department’s record-keeping. He disclosed that data on shootings is “missing, inaccurate, lost, or lacking in basic internal integrity.” This, he said, undermines the department’s ability to thoroughly track and analyze the use of deadly force, an issue that carries with it powerful community emotions and potent financial risks for the county.

Sheriff Lee Baca had no immediate comment. But department executives, who were shown a copy of Bobb’s report last week, questioned some of its methodologies, assumptions and conclusions—especially those involving race. In some cases, they say, the report relies on dated information from the 2000 U.S. Census. They also expressed concerns that reporters might take some of the report’s sharply worded statements out of context.

As a result, Bobb agreed to include with his report a five-page “transmittal letter” addressed to Baca. In it, Bobb reiterates his findings but stresses that he is not contending that any shootings were racially motivated.

“Your staff has expressed concern that the media might misinterpret this report because of its frank discussion of the race and ethnicity of persons shot by the LASD,” Bobb wrote. “It would be a serious error for anyone to conclude from this report that LASD deputies intentionally shot any individual because that individual was black or Latino.”

He added: “The LASD’s beef should be directed more at the media than at the messenger.”

Bobb’s report examines hit-and-miss shootings between 1996 and 2010, a 15-year span during which 178 persons were killed by sheriff personnel and 204 were wounded. For the most part, however, he focuses on the past six years.

Although the numbers cited in the report are not large enough for formal statistical conclusions, Bobb and his staff reached their findings on racial breakdowns by, among other things, comparing shootings with overall arrest rates. By this measure, the report argues, Latinos are “overrepresented,” meaning that they are fired upon more often than other races when compared to their arrest rates. White individuals, the report says, are “underrepresented.”

“This disproportion is particularly stark,” Bobb writes, “in the year 2007, when a full 72 percent of all shootings Department-wide involved Latinos. Shootings of African Americans by LASD personnel appeared more proportionate to the overall arrest rate than that of other groups.”

The report also breaks down the race of the deputies involved in the shootings; 47 percent were Latino, 42 percent were white, 7 percent were black and 2 percent were Asian American or Filipino.

Bobb says one of the study’s most troubling findings involved a spike last year in so-called “state of mind” or “perception” shootings, those in which a deputy believes, accurately or not, that a suspect is armed or is reaching for a weapon. In 2010, these increased by 50 percent, from 9 to 15, according to the report. Of these, 8 suspects were wounded.

None of these 15 individuals were later confirmed to be carrying a firearm, though some may have had time to dispose of one before their apprehension. In these “state of mind” shootings, Latinos and blacks also were disproportionately represented, according to Bobb.

“It goes without saying that such incidents, particularly where the victim turns out to be unarmed, carry the potential for great tragedy,” the report states. “They also present a risk of significant liability to the County and may make the work of LASD deputies more difficult by fomenting distrust among the population they serve.”

Bobb’s report calls on the department to reevaluate and improve its training, while doing a better job of collecting data to track and reduce such shootings.

Bobb also urged the sheriff’s officials to scrutinize the reasons behind the Century Station’s consistently high number of shootings—nearly double the number at the department’s next busiest station, Lennox. Century is based in Lynwood and includes some of the region’s most active gang neighborhoods, including the Florence-Firestone area.

Although it would be expected that a station like Century would have more shootings, Bobb says the number has remained high even as homicide and violent crime rates have fallen, a trend that he argues should lead to fewer cases of deadly force.

He said that 56 percent of all shootings at Century, involved a deputy who’d been involved in an earlier incident. Deputies there also had “relatively poor results” in attending annual or bi-annual refresher “shoot/don’t shoot” training. (Deputies do, however, engage in other shooting scenarios at the practice range.)

“We urge the department,” the report says, “to focus intensely on Century and its performance in this area.”

Posted 9/22/11

Updated 9/22, 6 p.m.:

Late today, Sheriff’s Department officials released a 26-page response to the Bobb report, mostly reiterating earlier complaints they had voiced with the special counsel.

Specifically, the department challenged Bobb’s “flawed analysis” in which he used comparative arrest statistics to conclude that Latinos and blacks were more likely to be the targets of lethal force than other races. The department said that Bobb used countywide arrest statistics, not those that would specifically account for the kind of violence and weapons deputies confront daily in gang-plagued areas.

The department also criticized Bobb for relying on outdated, 2000 Census information. During the past 10 years, according to the department’s response, the Latino population within the sheriff’s territory has increased 21%, further skewing Bobb’s analysis.

As for “state of mind” shootings, the department acknowledged that, in 2010, deputies fired at 15 unarmed people, hitting 8 of them. But the department said that “all of them involve suspects who were engaging in activity that was criminal in nature, non-compliant or both.”

Department officials also took issue with Bobb’s contention that many deputies were not complying with departmental training mandates that would help them determine when—and when not—to shoot. They said this training could be fulfilled through various courses, not just the one identified by the special counsel.

The department did agree that elements of its data collection could and will be improved.

To read the sheriff’s complete response, click here.

Fighting fire with some super friends

September 25, 2011

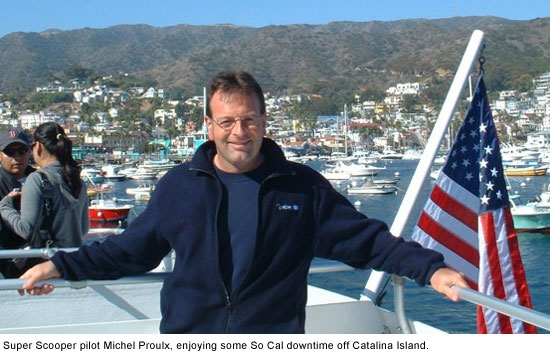

Michel Proulx has spent so many autumns in Los Angeles that he’s now a regular at pickup hockey games in the San Fernando Valley. Stéphane Monette has used his off-hours to teach himself to speak Spanish and to surf. One year, it was so dry for so long that Christmas came and went before Carl Villeneuve could return to his wife and three children near Quebec City.

Michel Proulx has spent so many autumns in Los Angeles that he’s now a regular at pickup hockey games in the San Fernando Valley. Stéphane Monette has used his off-hours to teach himself to speak Spanish and to surf. One year, it was so dry for so long that Christmas came and went before Carl Villeneuve could return to his wife and three children near Quebec City.

“It was OK,” he recalls with a laugh in his French-accented English. “You do not have snow in Los Angeles, but you have a lot of the winter decoration. One time in each four or five years, it is not so bad.”

For the past 18 years, an elite band of French-Canadian pilots and mechanics has left the Quebec backcountry to spend their autumns—and occasionally their winters—fighting fires in Los Angeles.

Fresh from their own wildfire season, they board two Bombardier CL-415 Super Scoopers leased from the government of Quebec by Los Angeles County. In the bright fixed-wing aircraft, which fly much lower and slower than commercial jet planes, they make the long trip south and west to the land of sunshine, celebrities and Santa Anas.

Once here, they check into the Burbank Holiday Inn—”our Hollywood house,” as Proulx jokingly calls it. Some meet wives and children. Some unpack sports equipment. Some pull out fiddles and guitars and hold Acadian jam sessions in their hotel rooms.

Then they get down to some of the most dangerous work on either side of the nation’s northern border.

“It’s really a unique situation, ” says Battalion Chief Anthony Marrone, who for the past seven years has acted as the Los Angeles County Fire Department’s liaison with the fliers from Canada’s Service Aérien Gouvernemental.

“They come here to risk their lives for people they don’t know, for a place that isn’t their country, for a job in which they’re not making a ton of money. But over the years, they’ve really become a part of our firefighting family.”

The famed Super Scoopers, which over the years have become a red-and-yellow icon of Southern California’s fire season, skim water from local lakes and the ocean and airdrop it onto wildfires. Los Angeles County has leased two of the sturdy aircraft during fire season annually since 1994, a year after the Old Topanga Fire killed three people and destroyed hundreds of homes in Topanga, Malibu and Calabasas. Each plane can pull in 1,620 gallons in 12 seconds, dump it and circle back at more than 170 miles an hour.

Marrone says the Super Scoopers cost the county about $2.75 million each fire season, which typically runs for 90 to 120 days, from September into December.

That price includes the pilots and their support crews, who work in 11-man rotations—four captains, four copilots and three mechanics. Each group stays for about a month, working out of the county’s air tanker base at the Van Nuys Airport, before a new group arrives via commercial airlines.

Over the years, the crews have been summoned to nearly every major fire in the county, particularly since the devastating 2009 Station Fire, when the U.S. Forest Service, which was managing the blaze, was criticized for not deploying more air power. The fire, the largest in county history, claimed the lives of two Los Angeles County firefighters while burning more than 160,000 acres and destroying some 200 homes and other buildings.

Since their arrival September 1, the planes and their crews have helped extinguish blazes in Newhall, Agua Dulce and Mandeville Canyon, among other hotspots.

“They’ve been there in Malibu, in the Buckweed Fire in Santa Clarita, in La Cañada Flintridge, in Diamond Bar and Palos Verdes, in Calabasas—everywhere,” says Marrone. “I was the helicopter coordinator on the Marek Fire in 2008 and they were out there long after any other air tanker would have had to turn back.”

The pilots downplay the danger.

“Sometimes we get bounced around when the Santa Ana winds pick up and we’re in the canyons, but mostly it is business as usual,” says Proulx, 46, who has been coming to L.A. since 2001. “We fly an aircraft that performs well in that kind of situation. When you’re using the right tool, it’s like driving a rig—it’s just a job.”

“We manage the risk carefully,” agrees chief pilot Villeneuve, who spent 11 years as a Canadian bush pilot before signing on with the Service Aérien Gouvernemental 15 years ago.

The biggest challenge, they say, is to keep track of all the moving parts of an urban fire scene. The wilderness of Quebec has its pitfalls, but news choppers and power lines and dolphins leaping in and out of the waves don’t tend to be among them. Nor do subdivisions and milling crowds.

The biggest challenge, they say, is to keep track of all the moving parts of an urban fire scene. The wilderness of Quebec has its pitfalls, but news choppers and power lines and dolphins leaping in and out of the waves don’t tend to be among them. Nor do subdivisions and milling crowds.

In Canada, Proulx says, their work mostly involves dipping into remote lakes to put out forest fires. But L.A. “looks like Legoland from the sky—I don’t know the English word for it, but the city goes on and on forever and ever. When we drop the water, we’re about 75 to 100 feet above the ground and we can see the people waving and all that. Sometimes we can see the firefighters’ faces down there.”

In fact, Monette says, one of his most vivid experiences here was in 1999 during his first L.A. fire season, when he looked down from the cockpit and realized for the first time just how high the human stakes would be on this job.

“The fires were so close to the people and the cities—it made me feel that to miss just one drop would be awful,” remembers the veteran pilot. Now 46 and the father of two teenagers in Quebec City, Monette has volunteered for the Los Angeles County contract at least a dozen times since that initial flight.

For the Canadians, the L.A. rotation is more than just a chance to hone their job skills. It’s also an opportunity to create a traveling hybrid of north-south culture. Some, like avionics technician Jean Larocque, go mountain climbing in their off hours. Eric Tremblay, 45 and on his first stint here, went to Lake Arrowhead during some time off last weekend. Jean-David St.-Laurent, a 37-year-old serving his second year in L.A., says he has taken to starting each day with a brisk 2-hour hike through the chaparral in Wildwood Canyon Park, near the hotel.

Monette is drawn to the beaches when he manages to get a day off; over the years, he says, he has acquired two surfboards. He also has worked on his communication skills. “I was surprised when I came here that everything was more or less in Spanish, not English, so I learned the language,” he recalls.

Coming to California, he says, “was a dream, since I was a little boy—this place is so associated with freedom, the California way of life.” The reality is, of course, more complex, he has since decided. “How free are you, really,” he asks, “when your way of living turns out to be an eternal rush hour?”

Proulx, whose rotation starts in October, plans to find an amateur hockey game as soon as he gets here, a habit he developed after he hooked up with an organization for Quebec expatriates online. “This year, I’m thinking about Burbank—I’ve already played in Simi Valley and Van Nuys.”

And, he adds, he’ll be bringing his fiddle.

“Another guy brings his guitar, and sometimes in the evenings, we have a few beers and play music until the bursar from the hotel comes and tells us to lower the noise.

“We play funny songs, dirty songs…My favorite one is called in English, ‘You’ve Broken the Chain on my Tractor.’ Hey, you got to do something besides just wait for fires.”

But the best part of coming to L.A., they say, is the chance to be of assistance.

Each year, they are touched by the grateful fan mail they receive. Once, they were feted by Topanga homeowners; another time, a classroom of schoolchildren drew them a packet of pictures.

And the Canadians have a secret: L.A. brushfires die more readily than Quebec’s tree-fueled conflagrations, especially with fire operations as well-run as those here.

“In Canada, we can be working on a fire for days and days and you can almost never see the end of it,” Proulx says. “But in L.A., you take off and see that big smoke, and every time, we know we’re going to go work hard and fight hard, but we got a good chance to win.”

Posted 9/14/11

Decision time for L.A. County

September 21, 2011

One way or another, history is likely to be made on Tuesday, September 27, at a momentous hearing to determine Los Angeles County’s political boundary lines for the decade to come.

Hundreds are expected to turn out for a final public airing of the competing redistricting plans that have sharply divided the Board of Supervisors in recent weeks. The plans known as T1 and S2 would radically redraw the boundary lines to create a district in which Latinos make up a majority of the citizen voting age population. The proposals would shift up to 3.5 million residents from their current electoral homes and split the San Fernando Valley into three districts instead of the present two. A third plan, A3, would keep current boundaries largely intact but still would reassign more than 277,000 people to new districts.

After the public has had its say during what is expected to be a spirited and long-running session Tuesday, it will be the supervisors’ turn to act. Their vote will represent a pivotal moment in the once-every-decade redistricting process in which supervisorial districts are rebalanced to incorporate population changes measured by the U.S. Census.

But it’s clear that this season of redistricting, aimed at evenly incorporating the 299,274 newcomers who arrived in Los Angeles County between 2000 and 2010, has been anything but a simple numbers exercise.

Board members must weigh an array of competing and compelling concerns—balancing issues of geography, community, ethnicity and race—and come together behind one of three proposed redistricting maps before October 1 in order to comply with the deadline established by the state Elections Code.

It’s a mark of the complexity of the debate that each of the three plans under consideration has a different supervisor behind it, with Gloria Molina backing T1, Mark Ridley-Thomas S2 and Don Knabe A3, while Zev Yaroslavsky has spoken out against T1 and S2 as a “bald-faced gerrymander” that needlessly breaks up communities. (Read his blog here.)

Because the County Charter requires the five-member board to pass a redistricting plan with at least four votes—not just a simple majority—the matter has the potential to veer off on an unprecedented course.

If four supervisors can’t agree on a plan by the deadline, then the decision would go before a special redistricting commission made up of District Attorney Steve Cooley, Assessor John Noguez and Sheriff Lee Baca. Although there have been hard-fought redistricting battles in the past, the “committee of three” apparently has never been called in to make the final call, said Martin Zimmerman, county assistant chief executive officer.

The state Elections Code specifies the composition of the panel and that the District Attorney serve as its chairman. In addition to the D.A., it mandates the participation of the assessor and a third elected official. Because Los Angeles County’s top elections official and school superintendent are appointed, the third slot here would fall to the sheriff, under the code.

Much of the redistricting debate has hinged on exactly what is required under the federal Voting Rights Act, and whether there is “racially polarized voting” in the county. Courts have ruled that “50% districts”—those in which one minority group makes up more than 50% of the voting age citizenry—are required only when voting is so racially polarized that non-minorities vote against minority-preferred candidates so consistently that those candidates are denied an opportunity to win. That’s not the case here, opponents of the T1 and S2 maps say, because Los Angeles voters of all races have shown time and again that they will elect Latino candidates, including Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, Sheriff Baca and Assessor Noguez.

Much of the redistricting debate has hinged on exactly what is required under the federal Voting Rights Act, and whether there is “racially polarized voting” in the county. Courts have ruled that “50% districts”—those in which one minority group makes up more than 50% of the voting age citizenry—are required only when voting is so racially polarized that non-minorities vote against minority-preferred candidates so consistently that those candidates are denied an opportunity to win. That’s not the case here, opponents of the T1 and S2 maps say, because Los Angeles voters of all races have shown time and again that they will elect Latino candidates, including Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, Sheriff Baca and Assessor Noguez.

Despite that, advocates for the T1 and S2 proposals contend that racially polarized voting does exist here and that the county must respond to it by creating a second district with at least 50% Latino citizens of voting age. Latinos now make up 48% of the county’s overall population and about one-third of its citizens of voting age.

Adding to the complexity of the debate are concerns voiced by some Asian-Pacific Islander leaders who say the T1 and S2 proposals could seriously undercut their communities’ voting clout.

Then there are those who point out that, by law, race and ethnicity cannot be the only considerations in redistricting decisions.

Many of them, from neighborhoods across the county, turned out for a public hearing earlier this month to urge the Board of Supervisors to keep together existing “communities of interest” under the A3 plan in order to handle pressing regional issues such as transportation and the environment.

The outpouring at that hearing came as part of a redistricting process in which the public, for the first time, was invited to design and submit its own maps using a new county website. In all, 19 plans were submitted by individuals and organizations—16 of them using the software on the county site. The site, which also features thousands of letters from the public and a wealth of links to data and documents, has drawn nearly 48,000 visits since it was launched in March.

And the public’s participation is not over yet. The Board of Supervisors’ meeting begins at 9:30 a.m. on Tuesday, September 27, in Room 381 of the Hall of Administration, 500 W. Temple St. Those who can’t make it in person can still make their views known by emailing [email protected] or sending a letter to the Executive Office, Board of Supervisors, Room 383, Kenneth Hahn Hall of Administration, 500 W. Temple Street, Los Angeles CA 90012.

Viewers also will be able to tune in to the meeting via live webcast.

Posted 9/21/11

Teaming up for all breeds of disaster

September 21, 2011

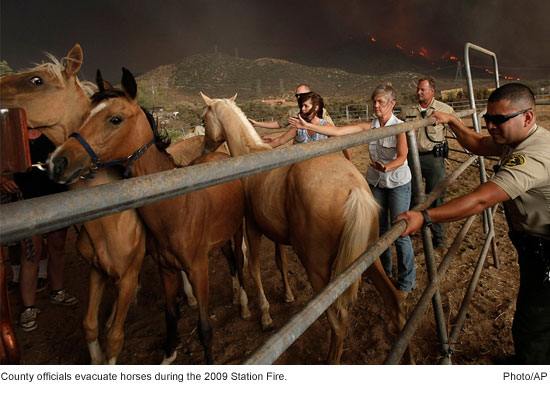

People aren’t the only creatures who need help in a natural disaster—just ask the buffalo who was rescued from its backyard during the 2009 Station Fire. Or the zoo animals evacuated in 2007 when Griffith Park burned. Or any number of feline or canine survivors of the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

People aren’t the only creatures who need help in a natural disaster—just ask the buffalo who was rescued from its backyard during the 2009 Station Fire. Or the zoo animals evacuated in 2007 when Griffith Park burned. Or any number of feline or canine survivors of the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

For years, when Los Angeles County has needed help rescuing animals in peril, local municipalities and nonprofit animal welfare societies have willingly pitched in. The system has had just one problem, says county Directorof Animal Care and Control Marcia Mayeda: It hasn’t been official.

Now that situation is about to change, thanks to a mutual assistance agreement that spells out the framework under which the county and animal welfare groups will cooperate.

“No one has ever had a problem,” says Mayeda, “but over time, we began to realize that signing a formal Memorandum of Understanding might be good.” Although local agencies always responded gladly, she says, disasters elsewhere made it clear that potential liability questions and lines of communication could be clarified and federal reimbursement could be streamlined if a formal agreement were put in place.

This week, to the relief of Southern Californians of many species, the Board of Supervisors set the process in motion, approving an MOU with the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Los Angeles.

Mayeda says the agreement, which lays out general lines of authority and resource sharing between the county and spcaLA, will help local officials respond to disasters more efficiently. Over time, she says, the department will ask other animal services agencies to sign on; the MOU can be expanded to include various humane societies and local animal control offices as co-signatories in times of need.

“There are about a dozen agencies like this that we’ve worked with in L.A.County,” she says. Cooperation is crucial, she says, because “a disaster or emergency knows no boundaries.”

“There aren’t a lot of us in the world who spend our time being concerned about the welfare of animals,” says Madeline Bernstein, executive director of spcaLA. “So we can get a lot more done when we help each other out in mutual aid.”

Bernstein says spcaLA has teamed up with the county informally on many occasions, manning shelters when county workers were out doing rescues, rounding up and dispersing food at pet evacuation centers, even joining forces with county investigators to help prosecute cases of animal cruelty.

During the Station Fire, she says, spcaLA helped the county feed and house countless animals who were rendered homeless by the conflagration near the Angeles National Forest.

“We had dogs, cats, birds, a very large pig, a llama they were trying to pull to safety,” she remembered. “A buffalo who was someone’s pet. We evacuated part of the Wildlife Way Station in conjunction with the county. In a disaster, there are all sorts of animals other than the ones you’d expect.”

Bernstein says Hurricane Katrina and other recent natural disasters spurred the move toward formalization.

“After Katrina, when we could see that people were choosing not to evacuate rather than to leave pets behind, it became clearer that a disaster plan should include animals,” she says.

“We have done exactly this forever,” says Bernstein. “This just puts forth a more organized face.”

Posted 9/21/11

Music stampedes the Broad Stage

September 21, 2011

Things will get a little wild and woolly on the Broad Stage in Santa Monica as “Carnival of the Animals,” Camille Saint-Saëns’ kid-friendly orchestral masterwork, hops, tweets and roars to life.

Things will get a little wild and woolly on the Broad Stage in Santa Monica as “Carnival of the Animals,” Camille Saint-Saëns’ kid-friendly orchestral masterwork, hops, tweets and roars to life.

The Broad Stage’s production combines classical performance with lively audience interaction, courtesy of conductor Rachel Worby. The composition’s fourteen movements are animal-themed, with names like “Tortoises,” “Elephants” and “The Aviary.” The music mirrors the behavior, sounds and moods of the animals, using jumping fifths for kangaroos, a double bass for elephants, and airy piano and flutes for birds.

Saint-Saëns composed the work in 1886 but didn’t allow it to be published until after his death, fearing its light-hearted motifs would damage his reputation as a serious composer. Since then it has become one of his most popular works.

There will be two performances this Saturday, September 24—one at 10 a.m. and another at 11:30 a.m. Tickets range in price from $20 to $35 and are available online. The Broad Stage is located at 1310 11th Street in Santa Monica; directions are on its website.

Posted 9/21/11

Check for the latest closure information

Check for the latest closure information