Better buy a ticket to ride

October 13, 2011

For Conrad Armour, the free ride came to an end Wednesday.

For Conrad Armour, the free ride came to an end Wednesday.

Not that the 23-year-old student was intentionally trying to evade the subway fare; he swears he inadvertently left his monthly pass in his gym locker. But on this particular afternoon, a gym locker was the worst possible place for that pass to be.

Metro officials, preparing for the first time to bring locked turnstile gates to local subway lines, are conducting a pilot test in four stations this month. That means spot-checking passengers’ tickets as they get off trains and monitoring ticket sales as incoming patrons realize they’ll have to pay to ride, or face the consequences. (A ticket for fare evasion can mean a $250 fine.) The test run is intended to explore, among other things, how many fare evaders the locked gate system could turn into paying customers.

As incredible as it might seem to transit riders from other big cities like New York and San Francisco, where locked gates are the time-honored way to prevent or at least slow down fare-beaters, Los Angeles’ subway was designed to operate on the honor system.

In recent years, Metro has taken steps to change that. In 2008, the agency’s board approved installation of a $46 million barrier gate system for L.A.’s Red Line and Purple Line subways as well as some light rail lines. At the time, it was estimated that fare-beaters cost the system $5.5 million a year, and that the system would begin paying for itself in its fourth full year of operation.

By last year, the turnstile gates were all installed but have remained unlocked while the agency tries to figure out how best to implement the new system. Still-unresolved issues include finding ways to handle passengers with paper tickets instead of the widely-used TAP “smart cards” that are designed to open the gates, and to incorporate travelers from other local transit lines that haven’t become part of the TAP network.

There’s also been debate over how far the amount of additional ticket revenue will actually go toward offsetting the cost of changing the system.

On Wednesday, Metro’s team directed patrons coming into the Purple Line’s Wilshire/Western station based on whether they had a TAP card, a paper ticket or no ticket at all. Vending machines appeared to do a brisk business selling to customers who may or may not have been planning to pay.

“It’s a lot more than a handful,” observed Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, who dropped by the station Wednesday as part of a small delegation of Metro board members including Santa Monica Councilmember Pam O’Connor, Lakewood Vice Mayor Diane DuBois and representatives from the office of Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa.

As part of the operation, fare enforcement officers were on hand to spot-check for tickets as passengers got off the trains.

While many people showed legitimate tickets or cards, many others did not. And the excuses were flying.

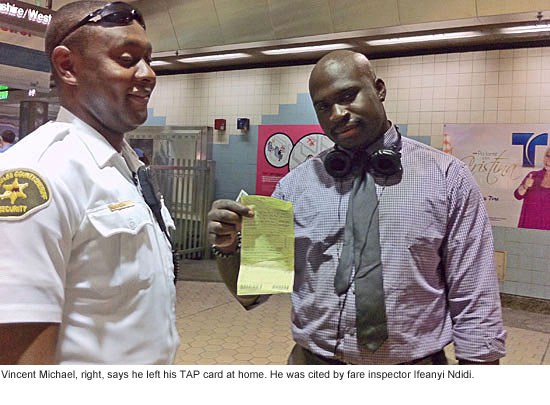

“The stories—some of them are good,” said Daniel Pickering, who along with Ifeanyi Ndidi was checking to make sure people had paid their fares.

Pickering said the body language could be a tip-off, with some patrons putting on an elaborate show of patting down their pockets, avoiding eye contact or rushing by flashing just the back of a ticket.

Some passengers—with and without tickets—got flustered.

“Where is that ******* ticket I got for $5?” one woman said as she angrily rummaged through her things before finally producing a ticket and hurrying on her way.

Another was escorted out of the station in handcuffs after a loud and lengthy exchange that escalated after she refused to sign her citation for fare evasion. (A sheriff’s patrol car was summoned but the woman was released after she finally decided to sign.)

The fare inspectors had the discretion to issue a warning or a citation. For example, a visiting student from France, Nathalie Karouni, was given the chance to purchase a ticket instead of getting a citation. And Isaac Taez, an 18-year-old student at the Friedman Occupational Center, got off with a warning.

Other travelers were slowed down a bit, like the 9th grade girls who had to wait for the one member of their group who’d forgotten her TAP card Wednesday and had to explain herself to the fare inspectors.

Sgt. Jeff Jablonsky, the sheriff’s department’s liaison to the TAP card/gating program, said 53 citations have been given out during the test program so far, with more likely next Wednesday, October 19, when all four of the test stations will be operating with locked gates from 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. (The stations are Wilshire/Normandie and Wilshire/Western on the Purple Line, and Vermont/Beverly and Hollywood/Western on the Red Line.)

In addition, he said, 5 people have been arrested, including a suspected graffiti vandal and a suspect with an outstanding warrant for a narcotics violation.

Jablonsky said that from what he’s heard, the transit-riding public supports locking the gates. “The comment that we’ve heard most of the time is, ‘It’s about time,’ ” Jablonsky said. “And we have other ones who say ‘I’m from New York and our gates are locked all the time. I don’t understand why your gates aren’t locked.’ The public is ready for it.”

That seemed to be the prevailing sentiment among travelers Wednesday. “I use the train, so I should pay for it. Otherwise I should walk,” said Sacha Larrabee, a 33-year-old grad student at Azusa Pacific University.

“It’s better because usually people come down here with nothing—no money, no TAP card,” said Alex Avalos, 18. “It’s like it’s free!” agreed Alyssa Segarra, 19.

Even some of those cited seemed more resigned than angry.

“I have a bus pass!” said Armour, the student who said he’d left the pass in his gym locker. “Unfortunately I just got caught up in it.” He said he was confident he could convince a judge to throw out the ticket when he produces the pass.

Vincent Michael, a 22-year-old security officer, said he also plans to fight his citation.

“I have a TAP card, a valid one, and I forgot it at home today, so I’ll just take it to court,” he said, before offering his support for the locked-gate project.

“It keeps everybody on their toes,” he said. “It makes everybody pay the fare.”

Posted 10/13/11

Missing a $26,234 tax refund?

October 13, 2011

Los Angeles County is $2.32 million richer this week, thanks to more than 6,000 unclaimed property tax refunds that have nowhere to go but the county’s general fund.

Los Angeles County is $2.32 million richer this week, thanks to more than 6,000 unclaimed property tax refunds that have nowhere to go but the county’s general fund.

State law authorizes counties to keep excess tax payments if no one claims them for four years. So every year about this time—as tax bills go out to millions of Southern Californians—the Treasurer and Tax Collector’s Office reluctantly deposits another pile of money from over-payers who couldn’t be located.

This year’s unclaimed refunds, from 2005-06, were only a tiny fraction of the more than $11 billion collected in the county that tax year. Many were for modest amounts ($1.59 was the smallest), but someone out there also failed to claim a refund worth $26,234.

Los Angeles County Assistant Treasurer and Tax Collector Nai-len W. Ishikawa says the county tries hard to track down recipients of refunds, and gets better at it every year; unclaimed overpayments have steadily declined for the past three years, even though collections rose during the tax periods involved.

But sometimes, the trail just goes cold, she says.

“Sometimes the property owner has passed away,” says Ishikawa. “Sometimes there’s been a change in ownership and we don’t have the person’s address.”

Typically, she says, overpayments occur when a tax bill has been inadvertently double-paid by spouses or a mortgage company and the county lacks sufficient information to generate an automatic refund. This, she added, can happen when the overpayment has been made via cash, a money order or an unaddressed check.

In other cases, the county gets a payment, but can’t apply it because the taxpayer forgot to include the bill stub or to write the parcel number on the check or wrote an invalid number, she says.

Although the vast majority of unclaimed refunds this year—about 5,500 items totaling about $1.43 million—were for overpayments, checks with missing parcel numbers or bill stubs hardly amounted to pocket change. In all, there were 942 of them, totaling about $880,000. The largest was $17,412.

Ishikawa says the county cannot issue a refund without documentation of an overpayment. But, she added, taxpayers can claim their money even after the 4-year deadline if the documentation shows that the county has made a mistake.

Donna Doss, the assistant treasurer and tax collector whose staff processes payments, says unclaimed refunds automatically go into a special file. Staffers in her office then begin the arduous process of finding and notifying the recipient before the 4-year deadline.

“We check our records to see if they own additional property in the county,” Doss says. “We look for any address on file within the county and send letters. We contact the title company.”

About 99% of the overpayments are cleared up, she says: “Often, we are able to locate people and they’re happy to receive their refund.”

But, she adds, staff is limited and searches can’t last forever. Each year, the county generates and processes about 2.3 million property tax bills. Less than one-hundredth of one percent of payments end up with unclaimed refunds.

“Our main mission is to collect taxes, after all,” Doss says. “At some point, you hit diminishing returns.”

Posted 10/13/11

Where’s The Rock?

October 13, 2011

For months, Los Angeles art fans have anticipated the arrival of the 340-ton boulder that will be the centerpiece of Michael Heizer’s massive new installation at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

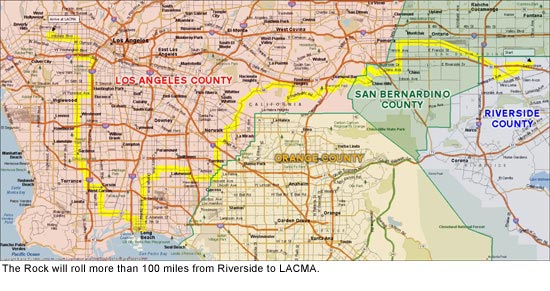

The Rock, as its minders have come to call the massive hunk of granite, was supposed to roll to Los Angeles in August from the Riverside-area quarry where, since 2005, it has been patiently waiting. The slow-speed odyssey, on the bed of a special truck, is expected to be almost as epic as the artwork, when it is finally completed.

Now, after many false starts and much speculation, a route has been finalized (click here for a map) and The Rock has a new date of departure—October 25, according to LACMA Director of Communications Miranda Carroll and the company orchestrating the move, Portland-based Emmert International.

So what’s been the holdup?

“Well,” jokes Carroll, quoting LACMA associate vice president John Bowsher, “you can’t hurry art.”

The more detailed explanation is that it’s not easy to transport a hunk of stone the size of a 2-story granite teardrop along more than 100 miles of urban surface streets and through the bureaucracies of four counties and more than a half-dozen municipalities.

Just assembling the transporter has been time-consuming. Custom built to The Rock’s dimensions, the special 2-truck contraption, whose segmented design has been compared to a caterpillar, has had to be assembled at the quarry, where the mover’s crews have tested and retested it.

Emmert specializes in transporting buildings, transformers, satellites and other massive objects, but unlike a piece of equipment, The Rock cannot be cut into components or easily strapped down.

Its weight, combined with its transport system, will total 1,210,300 pounds, says Emmert’s director of operations, Mark Albrecht. And because it is not just a boulder but part of an artwork, it must arrive at LACMA intact—no chips, no scratches.

So part of the time has been consumed in arranging the transporter’s complex system of tires and axles so that The Rock is secure and the weight is spread safely. Albrecht says each axle line will carry about 49,000 pounds, less than the weight spread of a standard tractor-trailer, and The Rock will be nestled on a special sling atop them.

“The thing fell off a 400-foot cliff when they blasted it out of the quarry, so I don’t think we can hurt it,” jokes Albrecht. “But we’re still handling it with kid gloves.”

Albrecht says preventing the rock from taking out traffic signals and low-hanging wires has been a major undertaking. He and his crews have had to coordinate with nearly 100 utilities in multiple jurisdictions to lift power lines, remove trees and get other obstacles out of The Rock’s path as it moves.

“Verizon alone has six or seven different areas,” says Albrecht. “The cable companies each have a bunch. And they don’t group up very well.”

Timing also has ramped up the degree of difficulty, says Albrecht, noting that this move is actually considered a rush job in the heavy-haul industry. Glitches are inevitable; bureaucracies are slow. Already, he says, the route has been adjusted three times to avoid roads and bridges that turned out to be weaker than expected.

“When you’re moving something this big, you usually have a year or year and a half lead time to work the permits, but we were just awarded the project in April,” Albrecht says.

The most recent snag has been a hardy Los Angeles perennial—parking. The Rock can only travel slowly and at night. The trip will require eight daylong stops in eight jurisdictions. “The problem is, where do you park something that long and that big and that heavy?” asks LACMA’s Carroll.

Ordinary parking lots aren’t an option, Albrecht says; the transporter is so wide and low-slung that just getting in and out would take six hours. That, in turn, would wreck the down-to-the-minute coordination with utilities whose wires will be cleared and replaced as The Rock moves.

“The route we have can’t change,” Albrecht says, noting that various bridge and overpass constraints have now narrowed the path to a single option. And security is an issue—pulling over also raises the risk that vandals might get to the precious cargo.

So for all but one break (a gravel lot in Pomona that will be its first rest stop), The Rock must be parked somewhere wide, flat, accessible to vehicles, easy to guard and hard to get to for humans. In other words, Albrecht says, The Rock has to park in the middle of the road.

Four jurisdictions (Pomona, Rowland Heights, West Carson and the City of Los Angeles) gave the thumbs up to the one-day disruption in each spot. But Albrecht says local officials expressed reservations in the other four.

So this week’s challenge was persuading Chino Hills, La Mirada, Lakewood and Long Beach that rush hour traffic could be funneled around a boulder, a 20-foot-wide transporter, an 8- to 10-man CHP escort and a flag crew, says Albrecht:

“All we need is someone to say, ‘Okay, we’ll allow it this one time.’”

By Thursday, the cities were mostly on board, and Albrecht was optimistic that The Rock will make it to its designated spot on the North Lawn of the Resnick Pavilion in time for the installation’s scheduled November opening.

There, the boulder will be placed atop the 465-foot-long concrete trench that makes up the other half of the artwork. The half-built trench will be finished, and when the artwork, called Levitated Mass, is finally completed, viewers will be able to walk into the trench and pass under the boulder—an experience that will make The Rock appear to float.

The $5 million to $10 million cost of the project, including its transport, will be borne by corporate donors, such as Hanjin Shipping, and private donors, including a number of museum board members. The experience is expected to be extraordinary, when The Rock finally gets here.

Its estimated time of arrival is November 4, a few hours before sunrise. At least that’s the plan for now.

Posted 10/13/11

Updated 10/25/11:

Newton wasn’t kidding with that stuff about an object at rest wanting to stay put. The Rock’s moving date has been moved again.

Just when it seemed a firm date had been set for the boulder in Michael Heizer’s “Levitated Mass” to be moved from its Riverside quarry, those parking difficulties with the various cities on the route flared up again last week.

“We’ve pushed it back at least week for now,” says Mark Albrecht of Emmert International, the heavy haul transporter handling the move for LACMA. This week’s sticking points: Lakewood and Diamond Bar.

The cities are balking at having such a large load on their roadways, Albrecht says, but the only feasible route to the museum is the one that has already been worked out. He says the cities have no need to worry—the route is more than sturdy enough to handle the cargo, but the permitting is being negotiated in a fraction of the time it usually takes to plan a move this large and complicated.

Talks continue, with more meetings scheduled for this week. Here’s hoping that everyone involved sounds like the opposite of these trick-or-treaters by Halloween.

Westside story—always a traffic drama

October 9, 2011

It’s official: Rush hour on the Westside is nasty, brutish and long.

A new report assessing potential routes for the Westside subway extension looks at current traffic conditions in the area to project what the future would likely bring, with or without a subway.

In doing so, it quantifies some of the modern-day commuter horror stories that have become the stuff of local—and international—legend.

The report offers a snapshot of a deeply dysfunctional network of freeways and surface streets in which rush hour traffic moves at less than 10 miles per hour. A major incident can bring the entire area to a standstill. (Remember President Obama’s motorcade last month?) Rush hour starts at 6:30 a.m. and continues till 10 a.m., then picks up for the afternoon onslaught from 3 p.m. to 7 p.m. “and beyond.”

“During a typical weekday evening, an auto trip along Wilshire Boulevard from Santa Monica to Beverly Hills takes up to 60 minutes to cover a distance of only 8 miles,” according to the report. “Morning and evening peak-hour speeds along Santa Monica Boulevard in Beverly Hills average less than 7 mph.”

The report’s analysis confirms what Westside road warriors have known—or at least suspected—for years. But the document, formally known as a draft Environmental Impact Statement/Environmental Impact Report, offers a level of detail that goes beyond anecdotal complaints.

Among its key findings:

- Of all the busy intersections in the 38-square-mile area around the proposed subway routes, Wilshire Boulevard west of Veteran Avenue is by far the worst, with daily traffic averaging 122,618 vehicle trips. It is followed by Santa Monica Boulevard east of Cotner Avenue (68,277) and Sunset Boulevard east of La Cienega Boulevard (66,043.) Among north/south surface streets, the most crowded intersections are Sepulveda Boulevard at Pico Boulevard, with 59,081 daily trips, and Bundy Drive south of Pico, with 59,022.

Click here for a list of all the key intersections and their daily traffic volume.

- Freeway interchanges, not surprisingly, are even busier. The Santa Monica Freeway at Bundy Drive averages 244,000 vehicles a day; at Crenshaw, the figure is 291,000. It’s even more jammed on the 405 Freeway, where the Olympic Boulevard interchange averages 319,000 vehicles daily.

- Some 42% of intersections in the area are flunking the test for rush hour navigability. With six “level of service” grades beginning at A (flowing freely) and ending at F (unacceptably congested,) 80 of the 192 intersections studied were rated an E or F.This map shows where rush hour traffic is most jammed.

- About 50% of Metro’s entire weekday bus ridership comes from routes that go through the subway study zone. Those buses, with some 550,000 boardings each day, average only 10-15 miles per hour on Wilshire, and 10-14 mph on Santa Monica. (The addition of a dedicated bus lane on Wilshire should improve average passenger travel times by 30%, the report said.)

The report did not compare the conditions in the study area to those elsewhere in the county, although it said: “Wilshire Boulevard represents the single heaviest used transit travel corridor in Southern California.”

Tom Jenkins, a consultant who acted as project manager for the subway extension report when he was with the firm Parsons Brinckerhoff, said there are certainly trouble areas elsewhere, such as in the San Fernando Valley and on the 101 Freeway. However, he said, when the subway study area’s concentration of jobs and activity are factored in, “you’re not going to find any area in the county that’s as congested.”

The draft report marshaled the data in order to make the case for building a westward extension of the subway. The routes under consideration could extend Metro’s Purple Line to Westwood or Santa Monica, with the possible addition of Red Line stations in West Hollywood.

In addition to analyzing the current traffic picture, the report looks ahead to 2035 and predicts worsening congestion in the area because of projected population and job growth.

Metro officials say the subway would not be a “silver bullet” to assuage all of the Westside’s traffic woes.

But the report noted that the area is highly urbanized and “built-out,” and has few, if any, options for adding or expanding roads. It stated that the only such project currently underway is the 405 Sepulveda Pass widening, which will add a 10-mile northbound carpool lane to the 405 as it heads away from the 10 Freeway.

“Local jurisdictions are not planning any major roadway expansion projects through 2035,” the report said, adding: “In the cities on the Westside, policy-makers have taken strong positions against the wholesale widening of streets and narrowing of sidewalks to accommodate more travel lanes.”

The subway, the report said, would offer a much-needed transportation alternative—one that is expected to be faster and more reliable than getting behind the wheel.

“The improved capacity that would result from the subway extension,” it said, “is the best solution to improve travel times and reliability and to provide a high-capacity, environmentally-sound transit alternative.”

Posted 9/09/10

Calling all job-seekers

October 6, 2011

Job-seekers in the San Fernando Valley may want to press that suit or polish those shoes for a very special event set to take place in Encino on Wednesday, October 12. It’s the first-ever “Valley Hiring Spree.”

More than 50 employers will have information and representatives on hand to meet and greet those looking for a new position, including retailers like Target, Ross, 99 Cents Only Stores, along with restaurants, government agencies, employment agencies, manufacturing firms, and others.

Specialized workshops will offer helpful advice on using social media to maximize your job search prospects, understanding the employers’ perspective, and other topics.

Be sure to bring your updated resume to:

Balboa Sports Center

17015 Burbank Blvd.

Encino

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

10:00am-1:00pm

For more information, visit www.TheValleyHiringSpree.com

Posted 9/6/11

Realignment gets all too real

October 6, 2011

Inside a cramped, dingy-white building in Alhambra, one of California’s most radical—and some say reckless—experiments in its criminal justice history is unfolding. There, officials are getting a detailed first look at some of the thousands of state inmates who’ll be supervised by Los Angeles County once they’re freed, a process that began this week.

Inside a cramped, dingy-white building in Alhambra, one of California’s most radical—and some say reckless—experiments in its criminal justice history is unfolding. There, officials are getting a detailed first look at some of the thousands of state inmates who’ll be supervised by Los Angeles County once they’re freed, a process that began this week.

So far, it’s not an encouraging sight.

Hundreds upon hundreds of prisoner files—some woefully incomplete—are haphazardly arriving by mail, fax and Fed-Ex at Los Angeles County’s “pre-screening” hub in the Probation Department’s Alhambra field office. Eagle-eyed probation workers are uncovering mistakes, large and small, in the state records, including inmates who should be sent to other counties and others whose crimes should disqualify them entirely from the new “realignment” program.

Only late last week, after intense pressure from L.A. County, did state corrections authorities even begin sending comprehensive mental health records on ex-convicts headed here for supervision, information that’s crucial in developing treatment plans for the clients and protection for the public.

What’s also become increasingly clear in recent days is that the state has not been entirely forthcoming about the fine print of the controversial realignment plan, which is aimed at reducing prison overcrowding while slashing the state’s budget deficit.

Again and again, the governor and legislature have publicly stressed that the ex-inmates who’ll be supervised by the counties are “low-level” offenders convicted of non-serious, non-violent, non-sexual crimes. They also note that these individuals would have returned to their home counties no matter who was responsible for their oversight. But that’s not the whole story, as L.A. County officials are quickly learning.

These same felons could—and sometimes do—have prior cases involving very serious crimes. Under the realignment law, AB 109, only the most recent conviction, or “commitment offense,” is considered in determining whether inmates will be supervised by counties or state parole agents after their release.

Take, for example, one inmate who was scheduled to be freed on Wednesday and has been ordered to report to L.A.County for post-release supervision. He was serving time for second-degree commercial burglary, attempted grand theft of personal property, forgery and identity theft—all non-serious, non-violent crimes under the penal code. But over the previous decade, he had more than a dozen arrests or convictions for a slew of serious and violent crimes, including assault with a deadly weapon, robbery and terrorist threats.

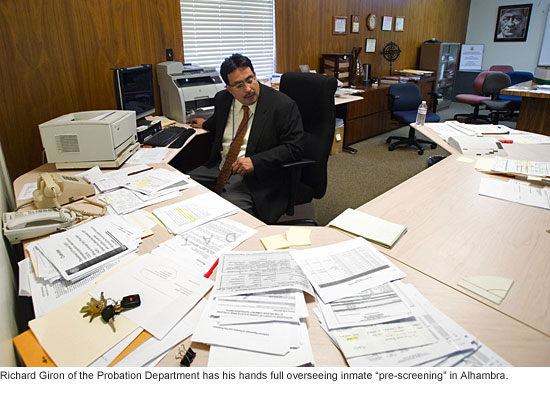

“We’re literally seeing every criminal record you could think of,” says Richard Giron of the Probation Department, who’s in charge of the pre-screening center in Alhambra, where nearly 2,000 files have been received. “We’re seeing prior violence, prior sex offenses—the full range of minimal criminal records to extensive, serious records.”

Giron says his staff is flagging such individuals for heightened supervision as part of the case plans developed when inmates arrive at other hubs throughout the region for face-to-face interviews.

Reaver Bingham, the Probation Department’s deputy chief of adult services and juvenile placement, called some of the county’s new charges “very hard core” but insisted that his agency is trained and prepared to deal with them. “This population is not unfamiliar to us,” he said, noting that the department currently supervises 15,000 adults with histories of serious and violent crimes.

In recent weeks, as AB 109’s October 1 implementation date drew near, concerns about public safety took center stage, with the harshest warnings coming from Los Angeles County District Attorney Steve Cooley. He predicted that crime rates would soar not only because of the freed inmates who’ll be under county supervision but because, under the law, defendants convicted of non-violent, non-serious crimes will now be sentenced to county jail rather than state prison. He and others argue that this will lead to even greater jail overcrowding and more inmates being released early by the Sheriff’s Department, which manages the sprawling system.

In the Alhambra screening center, Giron and his hand-picked team understand the high stakes for public safety and are determined to make sure no inmate is erroneously placed under the county’s jurisdiction. His 11 deputy probation officers and two supervisors scour every document the state sends and then comb criminal databases, as well as court records, for additional information on each of the inmates scheduled for release.

In the process, Giron says, his staff has uncovered mistakes that have given county officials ammunition to keep dozens of inmates from falling under probation’s purview.

“I’m doing everything I can in my power to reject cases that are inappropriate for supervision in L.A. County,” Giron says. Those cases have included an inmate who’d been serving time for molesting a child under the age of 14, a prisoner convicted of a serious extortion attempt and yet another who was described by the state’s own prison board as not safe to be released.

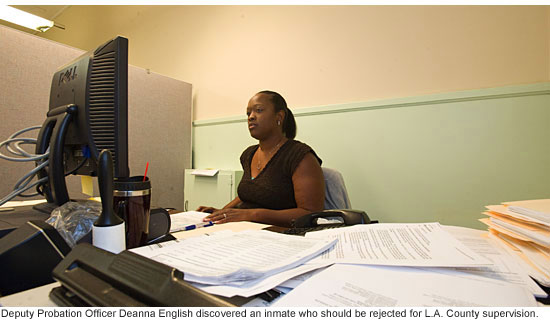

On Wednesday morning, Deputy Probation Officer Deanna English, a 22-year veteran of the department, found yet another, using the scant information contained in the state’s own file as a springboard.

Corrections officials had determined that a 20-year-old inmate at the California Rehabilitation Center in Norco was eligible for county supervision because, according to a release form, he was serving time for a second degree burglary. But that was wrong. Contained within the file itself was the notation that he’d been sentenced for a robbery, a serious crime that would exempt him from the realignment program. English says she then checked the actual court record, which confirmed the robbery conviction.

“Honestly speaking, I thought they were trying to pull one over on us,” she says of corrections officials. “Their thing is to get as many [inmates] out of the state system as they can.” English says she feels “a high sense of duty” to thoroughly vet every file.

Making the job even more challenging for the Alhambra crew is the fact that the state has no centralized point of contact. The county is receiving files from 33 separate prisons. And those files are not being sent based on the chronological release dates of inmates, dates that seem to be constantly shifting.

Just the other day, as Giron talked with a visitor from Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s office, another probation supervisor, Al Montellano, walked up with a handful of documents fresh off the fax. They stated that eight inmates scheduled for release on December 4 will now be freed on October 23, meaning that the time-consuming review of their cases will have to be rushed into the mix, putting others on hold.

“That,” Giron says with a hint of understatement, “is operationally inefficient.”

Progress finally has been achieved, however, in one of the most crucial facets of the screening process—determining the mental health status and needs for the estimated 20 percent of inmates coming to the county who’ll need some level of treatment.

For months, the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health, a key player in the realignment process, had been stymied in its efforts to obtain comprehensive treatment records for inmates. The information provided by the state was simply a notation that mental health services had been delivered in prison.

“We were getting promises and assertions that were not true,” says Dr. Marvin Southard, director of mental health. “It was very frustrating.”

Among other things, Southard says his department was directed to dial an information number on the inmate forms. “If you call that number, you get a correctional counselor—the cell-block staff person—but they have no access to the medical records,” Southard says.

Further, according to Southard, his staff was told that they’d have to individually contact each of the state’s 33 prisons for information, which would consume crucial time in learning an inmate’s needs and creating a treatment plan.

The issue reached a boiling point two weeks ago when the Board of Supervisors voted to send a stern letter to Gov. Jerry Brown. In it, they warned that, unless the necessary information was forthcoming, “we will not accept parolees with mental health issues.”

“After that, everything changed,” Southard says, noting that a centralized system was developed by California’s corrections officials. “The governor’s staff promised that we’d get the records we need.”

Still, even if the county manages to overcome all these logistical challenges, there’s still the overarching question of whether the state will provide the money necessary to make it all work today and in the future.

“This has been my concern from Day One,” says Supervisor Yaroslavsky. “We’ve been asked to take a leap of faith that the reimbursement is adequate to meet our responsibilities. You can’t blame us for being skeptical, especially given the problems that have emerged in the opening days of this program. Even though the governor has assured us he will make us whole, it’s not entirely up to him and that makes me nervous.”

Posted 10/6/11

An Idle chat with Renaissance author

October 6, 2011

Stephen Greenblatt is coming to Beverly Hills to discuss his newest book next week—and he’s bringing reinforcements. Comedian Eric Idle will join him for a talk that’s likely to be informative, witty and—for Monty Python fans—something completely different.

Greenblatt’s book, The Swerve: How the World Became Modern, is a bibliophile’s dream. A 15th-century Italian book collector travels on horseback across Europe in a quest for ancient Roman manuscripts. He discovers a 50 B.C. writing that sets the stage for thinking during the Renaissance and beyond: Lucretius’ “On the Nature of Things.” The shocking ideas of the text bring him face to face with the power of the medieval Catholic Church.

Greenblatt, a Harvard professor, also wrote the bestselling Shakespeare biography Will in the World. Known for including personal stories in his interviews and writing, he has told how he once literally ran into T.S. Eliot (knocking him over), played guitar with Art Garfunkel at a summer camp, and performed with members of the group that became Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

Greenblatt, a Harvard professor, also wrote the bestselling Shakespeare biography Will in the World. Known for including personal stories in his interviews and writing, he has told how he once literally ran into T.S. Eliot (knocking him over), played guitar with Art Garfunkel at a summer camp, and performed with members of the group that became Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

He’ll be chatting about his new book with Idle, whose own expertise on medieval life and religion were famously displayed in the 1975 film Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Idle drew from it more recently to create the popular musical “Spamalot.”

The Tuesday, October 11, conversation is presented by the nonprofit literary group Writer’s Bloc. It takes place at 7:30 p.m. at Temple Emanuel, 300 North Clark Drive in Beverly Hills. Tickets cost $20 and must be paid for in cash or check at the venue. Reserve a seat by emailing [email protected].

Posted 10/6/11

Putting a foot down on Alzheimer’s

October 6, 2011

The fight to end Alzheimer’s disease is moving forward one step at a time in hospitals, homes and research labs. On Sunday, a few million steps will be taken in a walk that’s part of the nation’s largest Alzheimer’s awareness and fundraising effort.

Since 1989, the Walk to End Alzheimer’s has raised over $347 million for Alzheimer’s care, support and research, battling a disease that currently afflicts 588,000 people in California alone. Each fall, more than 600 communities across the county participate in the walk, which is organized by Alzheimer’s Association. Last year, the Los Angeles walk drew about 4,000 people. Organizers expect a similar turnout this year.

Registration is free, and may be completed online or in person. Walkers set fundraising goals individually or as a team, and commemorative T-shirts will be given to those who raise $100 or more. The event website offers online fundraising tools to assist.

A “family festival” also will be held, with free snacks and coffee, live music, games, and booths with health and advocacy resources.

The walk heads out from Century City’s Century Park this Sunday, October 9, at 9 a.m. On-site registration opens at 7 a.m. If you can’t make it, you can still join the fight by donating online. If you go, bring comfortable shoes and sunscreen, and put your foot down on Alzheimer’s.

Posted 10/6/11

A big wheel in L.A.’s bike world

October 5, 2011

If there’s a geographic birthplace for Los Angeles’ burgeoning bicycle culture, it’s Eco-Village, the cooperative living compound tucked away on an East Hollywood side street and home to many of the activists who over the past 15 years have sparked an improbable cycling revolution in this most car-loving of cities.

And if you’re looking for someone who was there for the birth and has remained a leading voice through the movement’s sometimes challenging adolescent years, meet Joe Linton, the affable, versatile and endlessly energetic community organizer—and longtime Eco-Villager—who’s on a mission to humanize L.A.’s streets, one lane, path and policy at a time.

Linton, along with a handful of other bicycle pioneers, has played a seminal role in Los Angeles’ ongoing transportation transformation—with the most visible and exuberant public manifestation of their years of work coming this Sunday, October 9, in the form of CicLAvia, in which 10 miles of city streets will go car-free for a freewheeling street festival/bike excursion/urban explorathon that’s expected to draw 100,000 participants.

Sunday’s CicLAvia, the third in what Linton and others hope will eventually become a far more frequent facet of Los Angeles street life, runs from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. on a route that stretches from Hel-Mel (the Heliotrope Drive and Melrose Avenue neighborhood that’s home to the community-christened Bicycle District) to Hollenbeck Park in East L.A. New spurs will extend the route north for the first time to El Pueblo de Los Angeles and south as far as the African American Firefighter Museum. (A route map and directions are here. Information on getting there via Metro—and navigating all the bus detours—is here.)

And Linton will be, as he has for so many of L.A.’s big moments in cycling, right in the thick of it. As a fulltime consultant to the event, he’ll be helping to deploy an army of some 400 CicLAvia volunteers (and he’s still on the lookout for more. Click here to sign up.) He’ll probably also jump in to serve as a “route angel,” assisting with simple bike repairs along the way. And leading up the event, he’s been blogging about what’s in store, from street chess to dodge ball to Balinese gamelan music, along with colorful overviews of what the new route will offer to the south and north.

And Linton will be, as he has for so many of L.A.’s big moments in cycling, right in the thick of it. As a fulltime consultant to the event, he’ll be helping to deploy an army of some 400 CicLAvia volunteers (and he’s still on the lookout for more. Click here to sign up.) He’ll probably also jump in to serve as a “route angel,” assisting with simple bike repairs along the way. And leading up the event, he’s been blogging about what’s in store, from street chess to dodge ball to Balinese gamelan music, along with colorful overviews of what the new route will offer to the south and north.

Linton’s CicLAvia portfolio, mingling big picture vision and in-the-trenches hard work, reflects his multifaceted approach to activism. Not only did he co-found the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition—the influential bike advocacy organization that helped shape the city’s recently-adopted Bike Plan—he also designed the organization’s first T-shirt. In addition, he’s worked for C.I.C.L.E., another prominent L.A. bike group.

Linton doesn’t look like a stereotypical cycling fanatic. On a recent morning in Eco-Village and the nearby Bicycle District, he wears the local equivalent of business casual—black polo shirt and khakis (although it must be noted that in his case the khakis are shorts.) He smiles often as he runs into fellow activists, and is candid about how far L.A.’s cycling movement has come—and how far it still has to travel.

“Some weeks I feel like we’re finally changing,” he says, “and some weeks I feel like ‘Oh man, they’re up to the same old tricks that they said they wouldn’t do.’ ”

Overall, he seems to be a glass-half-full kind of guy. A vigilant monitor of how government agencies follow through on their commitments—he’s watching the progress of the city’s bike plan closely—he also sees the importance of selling his fellow Angelenos on the notion that making streets friendlier for cyclists will improve everyone’s quality of life.

Thus, no car-hating here: “I don’t think we need to fight against cars. I think we need to promote fun, wonderful alternatives and the cars will gradually fade away. We’ll still use them for things that we really need them for but I think they’ll be less and less in demand.”

He shrugs off being called a “founding father” of the movement—“I think I am just one of many folks who are working hard on this”—but it’s hard to find anyone who’s contributed more, or longer.

So how’d a fellow from suburban Orange County end up helping to rewrite the rules of the road in one of the largest and most vehicle-entrenched cities on earth?

Well, like the best bike paths, Linton’s route has had some interesting curves in it.

Linton, now 48, grew up in Tustin and remembers riding his bike all over, including to the ocean by way of the Santa Ana River Trail. A visual artist and author as well as a cyclist, he studied biochemistry at Occidental College but “got politicized” and left the pre-med track. He lived and worked for a time in Long Beach, ditched his car, moved to L.A. and got a job as a systems analyst at Children’s Hospital. At the same time, he plunged into the world of activism, notably on behalf of Friends of the L.A. River.

By 1996, he was living at Eco-Village, where the Bicycle Kitchen, the non-profit bike repair organization that would also become a major player in L.A.’s cycling evolution, was born in the compound’s actual kitchen. Before long, he was a fulltime activist.

Talk about being in the right place at the right time.

“We like to consider LA Eco-Village as the center of bicycle culture in L.A.,” says Lois Arkin, Eco-Village’s founder, who on a recent morning was strolling along a shady back path at the compound, a basket of just-harvested guavas on her arm. “It all emanated from here. This is where it all started.”

You can see why. With its backyard composting, potluck dinners, bicycle room, solar dryer (read: clothes line) and egg-laying hens, Eco-Village is a full-on green living demonstration incongruously come to life right behind a bustling Vermont Avenue strip mall complete with Little Caesars and KFC. The buildings will soon be owned by a residents’ cooperative and the land held by a community trust, to ensure that the same mix of very-low-to-middle-income residents can always live there, Arkin says.

It’s the kind of place that gives a $20-a-month rent discount to residents who don’t own a car. Where else would L.A.’s bicycle revolution begin? Arkin credits Linton and other residents such as Ron Milam, who with Linton co-founded the bicycle coalition, and Bobby Gadda, who helped import the CicLAvia concept from Bogotá and now serves as its board president (as well as one of Eco-Village’s resident beekeepers.)

There’s a lot riding on their efforts—and on CicLAvia, Arkin says: “The big goal for Angelenos is for us to overcome our stereotype and our stereotype is that we’re car-centric. We simply need to transcend our stereotype. That may give the whole world hope and more optimism.”

Nearby, the Bicycle District stands as an example of transcended stereotypes. As traffic buzzes by on Melrose, this stretch of Heliotrope is buzzing in its own way. Bicycles and a few cars line a walkable block that’s home to an organic coffeehouse, hip eyeglass boutique and Scoops ice cream shop, as well as the Orange 20 Bikes store and the nonprofit Bicycle Kitchen, which has relocated from Eco-Village’s kitchen to its own storefront. (The original kitchen’s now a food co-op.)

“I always describe this as our slice of Portland,” says Matt Ruscigno, a public health consultant specializing in vegan nutrition. “This is phenomenal. I mean, look at all these bikes.”

And everybody, it seems, knows Linton.

“A lot of bike energy is concentrated here,” Linton says. “It’s way cooler today than it was in the ‘90s.”

As if to prove his point, up rolls Kelly Martin, “operations facilitator” at the Bicycle Kitchen. As she takes off her bicycle helmet and opens the door, she and Linton reflect on CicLAvia’s bigger meaning.

“What CicLAvia does is it slows L.A. down to the pace of a cyclist or a walker,” Martin says.

“It’s a democratization of public space,” Linton agrees. “If you take the cars away, it becomes a really egalitarian space.”

On this morning, less than a week before CicLAvia, he’s pushing a simple message: “I think a healthy city gives people options. You should have choices for trips, and you use the one that works for you.” (In this part of town, though, it’s clear that going without a car is a badge of honor, with people exchanging their number of car-free years as easily as their phone numbers. Linton’s number is 20. He bikes just about everywhere, although he travels by foot and public transit a fair amount, too.)

Nearby, Ron Milam, Linton’s bicycle coalition co-founder who now has his own consulting practice, sits at one of Cafecito Organico’s sidewalk tables. He takes a few minutes to reminisce about the early days, and victories like bike lanes on Silver Lake and Venice boulevards, and getting Metro to increase its funding for cycling and pedestrian projects.

“Of anybody, Joe put the most time and energy into it,” Milam says, recalling that while others debated whether a bike coalition was needed in L.A. County, “Joe said, ‘Absolutely, let’s do this!’ ”

When that can-do spirit hits the streets Sunday, CicLAvia participants are likely to experience something fresh, whether they traverse the route on two wheels, or two feet.

“Cyclists and pedestrians can share spaces,” Linton says. “They do it all over the world; they do it all over L.A. That’s what makes cities great. We all need to enter the mix and be respectful.”

Posted 10/5/11

Check for the latest closure information

Check for the latest closure information