Vowing a fairer future

March 27, 2013

In October 2008, Supervisor Yaroslavsky officiated at the marriage of Rita Romero, left, and June Lagmay.

During my many years in public life, there’ve been just a handful of times when I’ve been caught off guard.

This week, as the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments on the constitutionality of California’s voter-imposed ban on same-sex marriage, I thought back to one of those surprising—and humbling—moments. It came some two decades ago when, as chairman of the Los Angeles City Council’s finance committee, I championed a measure to provide domestic-partner benefits to couples who’d been living together for more than a year.

After the vote, the committee’s clerk asked whether she might speak with me for a moment. By then, the hearing room at City Hall had cleared. It was just the two of us. I figured she had some committee business to discuss. And, in a very deep and unexpected sense, she did. She revealed that she’d been living with a partner, a woman, for nearly 20 years. “I just want you to know,” she said, “that this legislation will improve the quality of our lives in a truly meaningful way. Thank you.” I was overwhelmed. It’s rare that you get to witness such an immediate and profound impact of a vote on a person’s life. That was a good day.

Throughout my career, I’ve worked hard to be a consistent advocate for groups and individuals marginalized by society, including gays and lesbians. From my earliest days on the City Council, I confronted the Los Angeles Police Department for wrongly harassing gays and lesbians. I was the first straight elected official in California to debate then-State Senator John Briggs over his infamous (and doomed) ballot initiative in 1978 that would have prohibited gays and lesbians from teaching in the public schools, a measure ultimately opposed by Ronald Reagan.

But until a decade ago, I didn’t embrace the movement for same-sex marriage. I didn’t see the point. Hadn’t we provided gay and lesbian couples with virtually all the benefits of marriage except a license? With so many other important fights to pick, was this among the most pressing struggles for our society’s well-being?

Then I got educated. I had a conversation with my daughter, one that reminded me of that old Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young song, “Teach Your Children.” In the final refrain, it calls out to the young listeners of the day to “teach your parents well.” And in my home, like millions of others across America, that’s what happened.

“What difference does it make to you, Dad, if same-sex couples want to get married?” asked my daughter, who was then in her 20s. Although it was a simple question, I couldn’t summon a satisfactory answer no matter how hard I tried. The core issue was no different than any other civil rights struggle: a right extended by government to some was being denied to others solely because of sexual orientation, putting it in the same class as other discrimination battles our nation has known all too well.

While some people have described their support of marriage equality as an evolution, it was more like a 180-degree revolution for me after that conversation with my daughter. In the ensuing decade, I’ve supported same-sex marriage and I campaigned against Proposition 8, the California ballot measure now before the Supreme Court.

I’m hoping that the justices go big, that they rule as unconstitutional any laws banning same-sex marriage anywhere in the country. Judging from their questions and observations from the bench this week, most experts think that’s unlikely. Still, I’m keeping my fingers crossed that the court will at least begin to get on the right side of history and strike down California’s Proposition 8, which enshrined discrimination in the state’s constitution.

Maybe if each justice had the chance to preside over a same-sex union, as I have, they’d have a better sense of why Americans increasingly favor marriage equality.

In the fall of 2008, during a five-month window when such marriages were legal in California, I was honored to be asked by June Lagmay and Rita Romero to officiate at their wedding. June was no longer the clerk for the City Council’s finance committee, as she was when we had that private chat in the hearing room so many years ago. She’s now the City Clerk for the City of Los Angeles, and she’d waited a long time to wed her partner of 40 years, a wait that had joyously ended when the California State Supreme Court ruled for marriage equality.

The couple’s home in Temple City was packed with friends and family. There were beautiful rings, champagne toasts and a big layered cake. But most of all there was love, the kind that’s full of understanding and acceptance, a love that’s too powerful to be contained by bigotry and bad laws.

Posted 3/27/13

Dry time for county’s new storm boss

March 27, 2013

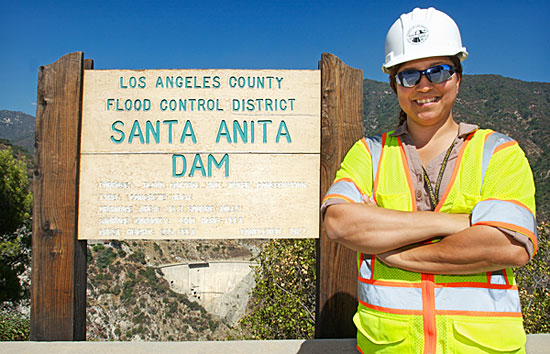

Meet L.A. County's storm boss, Michele Chimienti. Rainfall's been light during her first winter on the job. Photo/Public Works

If this was a normal year, water would soon be gushing from the Los Angeles County dam system’s reservoirs. It would be surging down rivers and channels, rushing into spreading grounds to be filtered and recycled, and flowing through wildlife habitats where it would sustain plants and animals through the long, hot summer.

But this is not a normal year.

For the second season in a row, winter storms have largely bypassed Los Angeles County and much of California. Local rainfall levels so far have reached only 37% of normal levels, and prospects for the kind of sustained, heavy rain required to make up the difference seem increasingly unlikely. (The storm that’s been forecast for this weekend isn’t expected to do much to bring county reservoirs—now holding just 5.5% of what they’d stockpile in a normal year—back up to where they should be.)

What’s more, a “new normal” seems to be emerging. Just ask Michele Chimienti, the county’s new “storm boss.”

“We’re seeing more of the high-highs and the low-lows. Nothing’s really normal. There’s no average,” said Chimienti, a county Public Works engineer who, since October, has been in charge of operations for the department’s water resources section. “You have one extreme or the other. Like in 2005, we had our historic wet year. That’s obviously an extreme. Then we had a dry year last year.”

For consumers, such extremes can be a pocketbook issue, with water rates going up and conservation programs aimed at lowering outdoor water use being heavily promoted—from “Cash for Grass” to “ocean-friendly” gardening.

For the water pros, the seasonal extremes are a challenge to business as usual. As hanging onto every possible drop of rainwater becomes increasingly crucial in Southern California, Public Works is accelerating its efforts to modernize and expand water retention capabilities throughout the region. (A list of completed and upcoming projects is here. Such efforts also are a central element in the proposed Clean Water, Clean Beaches parcel tax; the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors has asked for more details on the measure before deciding whether to place it before voters next year.)

And for those like Chimienti on the frontlines of storm water management, the dry spell has posed its own kinds of challenges—of the lonely Maytag repairman variety.

“I actually would have loved it if we’d had a wet season. That’s what we thrive on,” Chimienti said. “It does get a little frustrating when we have dry year upon dry year.”

Still, she and her team are using the time in which they’d ordinarily be controlling and diverting fast-moving stormwater to make needed repairs and upgrades to the system.

“This is our downtime right now because it has been such a slow storm season,” she said, “so we’re looking toward the future: what can we do to improve our water conservation in all of our facilities?”

Even though she hit a dry patch in her first winter on the job, the 40-year-old Chimienti has seen plenty of storm activity in years gone by.

“You can volunteer for storm duty, and I did that for the past six, seven years,” she said. “It’s a good way to learn the facilities. You see the river. You see how it reacts. You get a good idea of the amounts of water, the quantity of flow that’s coming down. You get to learn the names of all the flood maintenance guys who actually do this day in and day out, run up and down the rivers, making sure people are out of the flow when water’s coming down, making sure it’s safe.”

Chimienti, the first woman to serve as the county’s “storm boss,” was named a Top Young Leader last year by the American Public Works Association, testament to her work in her previous assignment: project engineer on the $100 million Big Tujunga Dam retrofit.

The work on “Big T,” as the dam is affectionately dubbed within Public Works, focused primarily on bringing the facility up to modern seismic safety standards. But an added benefit was that a reinforced reservoir could hold—and hang onto—much more water in the wet years.

“We’re able to conserve an additional 4,500 acre feet a year,” Chimienti said. (An acre foot is approximately 326,000 gallons.)

That kind of capacity is crucial when the amounts of rainfall vary so widely from year to year. As for what’s behind the variations, Adam Walden, senior civil engineer in Public Work’s water resources division, said they might be attributable to climate change but “we don’t know for sure.”

“What is known is that, in recent years, we are seeing extremes in L.A. County’s rainfall,” according to Walden. “We have had both the wettest year on record (40.5 inches in 2004-2005 season) and the driest year on record (3.6 inches in 2006-2007 season.)”

And that, Chimienti said, means it always makes sense to conserve.

“Don’t waste it,” she said. “It is a vital natural resource, and it’s not limitless.”

Effects of dry winter are visible at county's Cogswell Dam in the San Gabriel Mountains. Photo/Public Works

Posted 3/27/13

These co-workers go the distance

March 21, 2013

Showing off the hardware. From left, Ernestina Rhind, Salene Giron, Maria Duron, Sachi Hamai and Avianna Uribe.

Among the thousands of runners at the start of the L.A. Marathon in 2011 was a nervous but excited band of sisters. It was their first marathon, and at their side was their “mother hen,” veteran runner Sachi Hamai, more commonly known by her official title—executive officer of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors.

Three of the women were on Hamai’s staff. The fourth worked for Supervisor Gloria Molina. For months, Hamai would lead them on pre-dawn runs of gradually increasing distances. Before they’d even hit the streets, she’d drive the route and strategically stash water bottles so the women wouldn’t have to carry them.

After one of their sessions edged above 13 miles, Hamai, who oversees the Board of Supervisors’ agenda, came clean with an agenda of her own. “We’re going to do a marathon,” she decreed. At the close of those morning training sessions, she began urging them to visualize what it would be like to cross the finish line into the joyous and proud embrace of family and friends

Hamai was so persistent that before the starting gun was fired on the morning of the 2011 marathon, Maria Duron of the executive office remembers thinking: “What am I doing here? Did I ever say yes?” In the end, she’s forever grateful she never said no. “When we started training, I couldn’t even run a mile,” she says. “When we finished, I said, ‘We did it!’”

All five women did, in fact, finish the race, one of the most grueling in L.A. Marathon history, with rain coming down so hard that the streets were sometimes shin-deep in cold water. “I felt so horrible,” Hamai recalls. “I thought they’d never run with me again.”

She was happily wrong. Since then, the co-workers have logged countless more miles together in a ritual that the women say has created not only strong bodies, but strong bonds. “There’s a lot of chatter during our runs, but it’s not about work,” says Hamai, whose running shoes are always within arm’s reach, even when she’s at her desk. “We listen to each other about our personal lives. We push each other. If one of us says, ‘Let’s just get some coffee this morning,’ someone else will say, ‘Let’s get it after the run.’ ”

Come Sunday, 26,000 runners will once again lace up for the L.A. Marathon, a 26.2 mile journey of sweat and blisters from Dodger Stadium to Santa Monica. This time, though, the coach will be on the sidelines. “My mind is willing but my body isn’t,” Hamai says. Instead, she’ll be rooting for the sole member of the team to brave this year’s race—Avianna Uribe, operations director for Molina. “They’ll be there in spirit,” Uribe says of her training partners in the board’s executive office.

Still, Uribe will have company from a few other county colleagues along the route, including Ryan Alsop, assistant chief executive officer for intergovernmental and external affairs. This will be his fifth L.A. Marathon. But unlike the county women, he runs solo. “I’m an intense trainer and I like to be in my own head,” says the 42-year-old Alsop, whose fastest marathon time is 3 hours and 16 minutes. Although the fleet-footed exec will be running alone—heavy metal music pulsing through his ear buds—he says he’ll be joined at the starting line by a first-timer, the county’s Sacramento lobbyist, Alan Fernandes, whom Alsop convinced to give it a shot.

Fernandes, a long time cyclist and modest runner, says he thought the L.A. Marathon would be a perfect way to get a street-level view of the county he represents. “I’m using it as a sightseeing tour,” says the Northern California native. Fernandes is hoping he’ll be able to make that tour all the way from stadium to sea. His longest training run a few weeks back was 20 miles, he says, and that one “really kicked my butt. Going another six miles is going to be pretty tough stuff.”

“I’m kind of nervous,” he admits, “but I’m going to try to be calm.”

Meanwhile, Hamai is going to try to stay optimistic about her future on the roads. “It’s sad because I almost feel like I might not be able to run that far again,” she says. Last year, she and Uribe ran two marathons—Los Angeles and Chicago—and a dozen half-marathons, all of which took a toll on her body. “I just need to back off,” she says.

But, apparently, not for too long.

The other morning, Hamai and her business-attired running crew—Uribe, Duron, Salene Giron and Ernestina Rhind—gathered in her office in the Hall of Administration to display their bounty of gleaming race medals for a county photographer. Hamai noted that the sign-up for the St. George Marathon in Utah—where she ran her first marathon in 1997—was beginning on April 1.

“You can bet I’ll be trying to get into that one,” she said, and then added with a sly smile: “And I’m going to get the other girls to sign-up, too.”

(To watch the race, consider taking Metro, which has nine stations along the course. And if you’re driving, watch out for street closures.)

In their matching Tinker Bell costumes for a half-marathon at Disneyland, from left: Hamai, Rhind, Uribe and Giron.

Updated: Avianna Uribe and Ryan Alsop finished the marathon in fine form. But Alan Fernandes, after months of training, was unable to make the trip to L.A. from Sacramento because he was sick. Hats off also to two other marathon finishers from the county workforce: Andrew Veis, assistant press deputy to Supervisor Don Knabe, and Mark Pestrella of the Department of Public Works.

A legend lives on, with library’s help

March 21, 2013

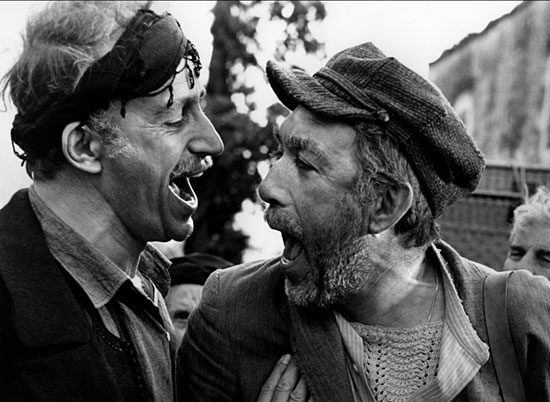

Heavy metal: the suit John Barrymore wore in "Richard III" is just one of the Anthony Quinn Collection's treasures.

There’s the suit of armor his mentor, John Barrymore, gave him. There’s the cap, now bronzed, that he wore in “Zorba the Greek.”

When Anthony Quinn left his papers to the East L.A. library on the site of the house where he spent part of his boyhood, the late actor defined the bequest broadly; there are movie stills, letters, handbills, art works, even a couple of Oscar nominations.

Less comprehensive was the plan to preserve the collection for posterity.

“Most of this came to us in boxes, which we changed to County Library boxes,” says Chicano Resource Center Librarian Daniel Hernandez, who oversees the Anthony Quinn Collection, a trove of some 2,000 items of personal and show business memorabilia that the artist gave to the county library more than 25 years ago.

The collection is a historical gem, offering a wide-ranging view of Quinn’s East Los Angeles roots and his life as a self-made man and 20th century film star, but its preservation has been a concern since Quinn made the donation in 1987, says Hernandez.

A few pieces—the suit of armor, the Zorba cap—have been used as library displays and a few others have been loaned to other museums for exhibits on show business or Latin culture. Most, however, have spent the past couple of decades in storage, he says, and the cardboard library boxes, while an improvement over the original containers, have hardly been a long-term solution.

“Everything has been safe,” says Hernandez, gesturing to a wall of cabinets, stacked floor to ceiling, in a locked room at the Anthony Quinn Library. “But even though it’s OK for right now, it’s not OK for the future to come.”

So this week, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors accepted a $6,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to help preserve the cache, from film scripts and taped interviews to thank you notes and birthday cards. The funding will, among other things, underwrite an assessment from a professional conservator and pay for appropriate preservation supplies and containers.

“There’s not that much knowledge of this collection,” says Hernandez, flipping through a draft of one of Quinn’s two autobiographies, typed and annotated on fragile onionskin paper. Next to it sat a cardboard box filled with gilt-framed black-and-white photos—Quinn as a young actor, Quinn in Italy, Quinn with his “Zorba” co-star Melina Mercouri.

“People are aware it’s out there but they don’t know what’s in it. One of our goals is to get that out into the public consciousness.”

Born in 1915 in the Mexican state of Chihuahua, Quinn—who inherited his surname from his part-Irish father, Francisco—came into the U.S. as an infant with his parents, who were migrant farm workers for several years before settling in Los Angeles. Here, Quinn’s father found work as a studio property man and the family moved into a house at the corner of Hazard and Brooklyn (now Cesar Chavez) avenues in East Los Angeles.

“I can’t tell you what an emotional thing it is to be standing on the spot my cousin beat the hell out of me,” Quinn joked to the Los Angeles Times in 1983, when the site—long since razed to make way for the county’s Belvedere Library—was renamed in his honor. In a more somber moment, the actor also said that when he was 9, his father had been killed in an automobile accident near the same corner.

Photos in the collection commemorate Quinn’s youth as a student at Belvedere Junior High School and Polytechnic High School, where he took courses in art and architecture, but, according to obituaries, never earned a degree.

After stints in Los Angeles as a boxer, a musician and even an evangelical preacher, Quinn tried acting. In 1936, he debuted in a cameo role in the film “Parole” and in a stage role that had been written for John Barrymore, a much older and more famous actor.

Among the papers in the collection is an account of his friendship with Barrymore, who took him on as a protégé after seeing the performance, and later gave him a suit of armor he had worn in Richard III, comparing it to the sword a retiring bullfighter hands down to “his preferred novillero.”

The suit—the largest item in the collection—is on display in the reading room of the branch library that now stands on the site of Quinn’s old homestead.

Quinn went on to act in more than 100 movies, working well into his 80s and winning two Oscars for best supporting actor—first as the brother of the Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata in “Viva Zapata!” and later as the artist Paul Gauguin in “Lust for Life”.

As his fame grew, he spent more of his time in Italy and New York than on the West Coast, but he maintained his local connections.

“He never forgot his people,” the sister of one of the defendants in the famous 1942 “Zoot Suit” murder trial told the Los Angeles Times at the 1983 library dedication, noting that Quinn—married by the time of the historic trial to the director C.B. DeMille’s daughter—had gone out on a limb both politically and professionally to help raise money for the appeal.

“He’s still pretty much of a local hero,” says Hernandez. “He’s an example of how you can work your way up and always care for your community. People here all seem to remember his aunt, or to have gone to school with him, so it’s a big social goal for us to save his works and preserve them.”

Quinn died in a Boston hospital in 2001 of respiratory failure. “But here in the community,” Hernandez says, “he’s very alive.”

Quinn won two best supporting actor Oscars, and was nominated for his star turn in "Zorba the Greek."

Posted 3/21/13

A mountainous achievement

March 20, 2013

After this acquisition, most of the land around Ladyface will be under public ownership. Photo/Agoura Hills Patch

Lovers of the Santa Monica Mountains soon will have 612 acres of new reasons to cherish the wilderness expanse at the edge of one of the world’s largest cities.

The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors this week approved two major acquisitions by the Mountains Recreation & Conservation Authority totaling 612 acres, including a vast expanse of land on the south face of the distinctive peak known as Ladyface Mountain.

“In terms of interior, non-coastal acquisitions, there hasn’t been anything this big in a long, long time,” said Paul Edelman, chief of natural resources and planning for the organization.

Preserving the Ladyface Mountain property—more than 525 acres in unincorporated Cornell, near Agoura Hills—means that a huge bloc of wildlife habitat will remain unaltered by development or other human activity. “It will always be there,” Edelman said. “It’s something we can count on.” The iconic views of the property, with its dramatic rock outcroppings, will continue to dominate the vista seen by those who travel along Kanan Dume Road.

Beyond the unspoiled beauty of the landscape itself, he said, placing the property under public ownership opens up vast new possibilities for how visitors will be able to use it.

“It creates a trail opportunity that few people have ever even dreamed of,” he said. For the first time, he said, the Pentachaeta Trail in Westlake Village will be able to connect across Triunfo Canyon and into the heart of the mountains.

The other property, in Escondido Canyon near Malibu, is much smaller—just over 86 acres. But its environmental, aesthetic and recreational significance is immense, Edelman said.

A central feature is a deeply shaded creek that flows year-round. Someone—no one’s sure exactly who—long ago created “a little bit of a Shangri-La” on the property, with a pond, terraces and picnic areas, Edelman said.

Both properties have drawn their share of headlines over the years.

Long-running development battles raged over an on-again, off-again plan to turn the Escondido Canyon property into a New Age retreat, featuring 95 of the Mongolian tents known as yurts, along with swimming pools, tennis courts, fitness facilities and meeting rooms. Now the property—made up of 34 separate parcels—will remain undeveloped.

Ladyface Mountain also has attracted plenty of attention, including a cheeky 2010 April Fool’s Day prank by the local newspaper, the Acorn, which claimed that a massive sculpture and aerial tramway—or “even a small bullet train”—were in the works for the site.

All joking aside, the Acorn also spent some time exploring the derivation of the peak’s unusual name—said to be a poetic reference to a Native American legend of the mountain’s distinctive outline—and concluded that it “had more to do with modern day marketing than Chumash Indian lore.

“The legend that tells of a lady peering into the skies waiting for the return of her warrior lover was fabricated by Art Whizin, a real estate developer and businessman who moved to the area in 1954 and wanted to build a restaurant on the crest of the mountain,” the newspaper reported.

When this latest acquisition by the Mountains Recreation & Conservation Authority is completed, the vast majority of land around the mountain will be in public hands and immune to any such development proposals in the future.

The purchase of both properties, at a total cost of $8.3 million, is being funded by 3rd District funds generated by, among other sources, Proposition A, the parks measure approved by county voters in 1992 and 1996.

Posted 3/20/13

Mapping the end of the road on the 405

March 14, 2013

A key part of the project, a new Skirball Drive onramp to the southbound 405, opened earlier this month.

With the massive 405 Project now two-thirds complete, officials have unveiled a staggered endgame schedule which calls for major portions of the project to wrap up this year while work on one troublesome segment continues into 2014.

The delay involves the project’s middle segment—chiefly in the area around Montana Avenue and Church Lane—where utility relocations and the necessity of shifting Sepulveda Boulevard have proved vastly more time-consuming than expected.

Overall, unforeseen utility relocation issues have not only eaten up valuable time but also have driven up the cost of building the project, according to a briefing presented this week to Metro’s Construction Committee.

Engineering challenges involving a single 12-foot-by-12-foot box encasing a storm drain under Sepulveda Boulevard were particularly problematic, project manager Mike Barbour told the committee. In addition, 16 retaining walls needed to be torn down and rebuilt because they were deemed to be structurally unsound.

Metro officials say that even with the unanticipated obstacles, the project’s “design-build” construction process, in which engineering takes place as work moves along, has saved hundreds of millions of dollars and seven years of building time.

As it stands now, virtually all of the utilities have now been relocated, and the project is on track to finish work on most major elements by year’s end—including the Wilshire flyover ramps and all three bridges that have been demolished and are being rebuilt as part of the project.

The heart of the undertaking is construction of a 10-mile northbound carpool lane on the 405 Freeway from the 10 to the 101. When completed, it will form part of a 100-mile carpool lane through Los Angeles and Orange Counties, believed to be the nation’s longest such stretch.

In addition to building the carpool lane and demolishing and reconstructing the Sunset, Skirball and Mulholland bridges, workers have realigned 28 on- and off-ramps, widened more than a dozen underpasses and constructed some 18 miles of retaining and sound walls.

The southernmost segment of the project, running from the 10 Freeway to Wilshire Boulevard, is expected to open by mid-year, while the north stretch is on target to finish by year’s end, Barbour said.

The sheer size and complexity of the project has made things difficult for those who live in the area, Barbour acknowledged. But the end is in sight.

“They’re getting through it,” he said in a recent interview. “We’re as frustrated as they are. It’s been a long, torturous job.”

Posted 2/21/13

Coldwater Canyon’s pipe with a past

March 14, 2013

Undated DWP photo shows pipe used for aqueduct. Smaller pipe of the same riveted steel built the trunk line.

It was 1913 when William Mulholland famously declared, “There it is. Take it.”

But it wasn’t until 1915 that thirsty folks down in the city of Los Angeles could actually take a swig of all that Owens River water pouring into the Los Angeles Aqueduct.

The missing link? The City Trunk Line, known at the time as the “San Fernando Syphon,” an underground water pipe stretching from Sylmar across the Valley (not yet part Los Angeles) through a tunnel in the Santa Monica Mountains to the Franklin Reservoir above Beverly Hills.

With the trunk line’s completion on June 6, 1914, and connecting pipes finished the following year, Mulholland’s aqueduct at last had a direct connection to the city whose growth it would fuel so explosively in the decades to come.

Now, 99 years later, a new generation of Angelenos is feeling its power. And not in a good way.

Commuters on Coldwater Canyon Avenue, a major thoroughfare between the San Fernando Valley and the Westside, recently learned that the street will be closing between Mulholland Drive and Ventura Boulevard for nearly five weeks, from March 23-April 25, so that the city’s Department of Water and Power can replace a 1.3-mile segment of the aging pipe. [Updated 4/24/13: Coldwater Canyon has been reopened, two days ahead of schedule, city officials announced. However, restrictions on left-hand turns are still in place through June 1.)

Clearly, the inconvenience will be sizeable. As Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky told reporters at a news conference this week announcing the closure: “You can put lipstick on a pig, but it’s still a pig. And this is a pig of a project.”

But he and other local leaders emphasized that the work is important—and unavoidable.

Corroded and susceptible to leaks, a section of the trunk line burst sensationally in 2009, sending millions of gallons of water bursting through the pavement and damaging homes and businesses around Coldwater Canyon and Ventura Boulevard. Earlier, in 2002, the line ruptured in Pacoima after workers inadvertently scraped the pipe, hastening corrosion on that segment to the breaking point.

The Coldwater Canyon closure comes after some 35-45% of the old pipe already has been replaced; modernizing the entire trunk line is expected to take about ten years, said Susan Rowghani, director of the DWP’s water engineering and technical services division.

About 25,000 gallons of water gush through the trunk line on the average each minute. With a diameter ranging from 62 inches to 72 inches in various places, the pipe is smaller than the massive pipes of the aqueduct itself, which range from 84 inches to 120 inches and were photographed at the time of construction with automobiles and even horse-drawn buggies parked comfortably inside. Other than size, though, the pipes used in the aqueduct and trunk line were virtually identical, made of the same riveted steel that was the construction standard at the time, said Fred Barker, manager of water transmission operations at the DWP and the agency’s unofficial historian.

Despite the trunk line’s ripe old age, he said, it’s far from unique in the city’s subterranean water world, where 287 miles of the DWP’s 7,289 miles of pipe date back to 1914 or before.

There’s even a cast iron pipe from the mid-1880s that still runs under 7th Street downtown for six to eight blocks, he said. There are no plans to replace it at the moment. “It’s performing very well,” Barker said. “There’s no need to replace a pipe that doesn’t leak.”

Sadly, the same can’t be said of the venerable City Trunk Line. So it’s with a sense of respect for history that Barker marks its inevitable passing from the scene.

“We talk about this event in 1913, when Mulholland and 40,000 people were out there and the water came down the hill and he said, ‘There it is. Take it.’ But the only way they could take it was in little souvenir bottles…if you wanted that water, you had to go out to Sylmar to get it.

“They had to get it to the city. This is the pipe that did it.”

Now the riveted steel pipe of a century ago is giving way to modern day welded steel—which, Barker said, “is going to last at least as long—and maybe twice as long.”

Posted 3/7/13

Making new connections in the Valley

March 14, 2013

There’s a new ride coming to the Valley—either a light rail or rapid busway. Now’s your chance to weigh in.

First came the Orange Line, a dedicated busway in the San Fernando Valley that gives folks from Woodland Hills to North Hollywood a speedy alternative to local bus lines or traffic on the 101. Ridership on the line continues to surge, and an extension to Chatsworth opened last June.

Now the focus shifts eastward. The East San Fernando Valley Corridor project, to be routed along Van Nuys Boulevard and San Fernando Road, is about to enter its environmental review phase.

“The Van Nuys corridor is the most heavily traveled north-south route in the San Fernando Valley, with about 25,000 boardings per day,” said Walt Davis, manager of the Metro project. “There is a need for a premium service to serve those people.”

During the environmental review phase, plans for the project will be studied in greater detail and refined. This Saturday, Metro will hold the first of four meetings to present the options as they now stand, and take feedback and comments.

“It’s a chance to better define the scope of what we’ll be looking at and for the public to tell us what their concerns and needs are,” Davis said.

Two alternatives will be studied. One is a light rail option and the other is a bus rapid transit line similar to the Orange Line. Either choice would go along Van Nuys Boulevard and San Fernando Road between Ventura Boulevard and the Sylmar/San Fernando Metrolink station. (Click here for a map of the light rail alternative and here for a map of the rapid bus alternative, which includes several sub-options south of the Orange Line). The line is scheduled to begin operating in 2018.

The rail alternative is projected to generate more riders, and it also comes with a higher price tag, somewhere between $1.8 billion and $2.3 billion. The rapid bus option is projected to cost between $250 million to $500 million. Currently, only about $170 million is dedicated to the project, so more funding would need to be lined up in either case.

In addition to serving immediate neighborhoods, which include shopping centers, schools, health care facilities and civic centers, the line will provide a fast link to other transit options. It will connect to Metrolink stations in Van Nuys and San Fernando as well as to the Orange Line, which in turn links to the Red Line and the rest of the Metro rail system. The south terminus of the line will be designed to connect to a future line between the Valley and the Westside that is under study.

The public meetings will take place at the following times and locations:

- Saturday, March 16, 10 a.m. to 12 p.m. at Panorama High School, 8015 Van Nuys Boulevard

- Tuesday, March 19, 6 p.m. to 8 p.m. at the City of San Fernando Regional Pool Facility, 208 Park Avenue

- Thursday, March 21, 6 p.m. to 8 p.m. at Arleta High School, 14200 Van Nuys Boulevard

- Wednesday, March 27, 4 p.m. to 6 p.m. at Marvin Braude Constituent Service Center, 6262 Van Nuys Boulevard

In addition to the meetings, Metro for the first time will accept formal comments on social media. Go to the project’s Facebook page and click on “Submit Scoping Comments” or tweet to @EastSFVTransit using the hashtag #ESFVScoping to take advantage of this option. Formal comments may also be mailed to Metro or submitted by email to [email protected].

Posted 3/14/13

Building on Pacific Standard Time

March 14, 2013

It’s big, it’s sprawling, it’s diverse, it could only have happened in Southern California.

You could be talking about L.A.

Or you could be talking about L.A. architecture, which is the subject of a big, sprawling, diverse SoCal initiative that launches next month, courtesy of the folks who brought you Pacific Standard Time, last year’s sweeping examination of Los Angeles’s place in the post-war art world.

“Pacific Standard Time Presents: Modern Architecture in L.A.” will celebrate the megalopolis’ man-made landscape with nine exhibitions and programs around the Southland, from tours of modernist homes in Pasadena to a first-ever major survey of Los Angeles’ postwar development at the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Underwritten by the Getty Foundation, which made some $3.6 million in grants to 15 participating organizations, the spinoff is about one-sixth the size of last year’s PST. “Obviously, we can’t do an initiative on the scale of Pacific Standard Time every year,” says J. Paul Getty Trust President and CEO Jim Cuno.

Still, it’s comprehensive. The Neutra ranch houses, the Norm’s diners, the Frank Gehry landmarks, the 405 Freeway, Beverly Boulevard photographed from a car window and Wilshire Boulevard explained for participants in CicLAvia—they’re all there (and more) in shows scattered from LACMA and MOCA to the University Art Gallery at Cal Poly Pomona.

Exhibitions are scheduled to run from April through July, though the heaviest programming will run from mid-May until mid-June. For a full list of events, click here.

Posted 3/7/13

Check for the latest closure information

Check for the latest closure information