Defenders mark a century of L.A. law

January 19, 2014

In this 1963 photo, Public Defender Kathryn McDonald confers with client Gregory Powell (left), who was accused with Jimmy Lee Smith in the "Onion Field" killing of LAPD officer Ian Cambell.

In the early 1880s, an Italian immigrant in San Francisco was charged with trying to collect $500 in insurance by torching his house on Telegraph Hill. The man was innocent but could not afford a decent attorney, and when his trial date rolled around, his lawyer didn’t show.

So the judge, as judges did then, went into the hallway and ordered the first lawyer he saw to represent the defendant. This didn’t bode well, since most court-appointed defense lawyers at the time were not only unpaid but also incompetent.

The lawyer—Clara Shortridge Foltz—was, in fact, just out of law school. But she won the case and used it as Exhibit A in a national push that led to the opening of the nation’s first public defender’s office in 1914 in Los Angeles.

One hundred years later, the Public Defender’s Office of Los Angeles County is marking its centennial anniversary. Some 700 attorneys work there now—more than at any criminal defense firm in the nation—along with hundreds of investigators, paralegals, psychiatric social workers and support staff. Last fiscal year, they defended clients in more than 400,000 felony and misdemeanor cases, not counting the thousands more defendants in juvenile delinquency and mental health courts.

Like Foltz, they occasionally make history. And, like Foltz, they tend not to become particularly famous. (In 2001, when the criminal courthouse downtown was renamed in her honor, the Los Angeles Times noted “a chorus of people saying: ‘Clara Who?’”)

“We usually pick up cases because nobody else is there,” says Alan Simon, a now-retired public defender bureau chief who spent five mostly unsung years representing the Hillside Strangler, Kenneth Bianchi.

“But most of the great names in public defense are not the ones that you see in the headlines. Charlie Gessler was probably one of the best defense lawyers ever. Do you know who he is? Probably not.”

Deputy Public Defenders Bernadette Everman and Dave Meyer at arraignment of "Night Stalker" Richard Ramirez.

Less obscure are some of the names of the clients represented over the years by the department. The Night Stalker had a public defender. So did the Onion Field killers and members of the Manson and Menendez families. Public defenders played a key role in uncovering the Rampart scandal at LAPD in the 1990s, and handled the crush of cases filed in the wake of both the Watts Riots and the L.A. Riots.

Most of the office’s clients, however, are the kinds of people to whom society tends to pay little attention—the impoverished, the downtrodden, the lost, the addicted, the difficult.

“It’s a calling,” says Public Defender Ron Brown, who has spent 33 years in the office, where turnover for reasons other than retirement averages a miniscule 2 percent a year.

“Our clients aren’t always nice people,” Brown says. “But somebody has to defend them, and vigorously defend them, in order for justice to be done. So what we do is about protecting peoples’ constitutional rights, and people who work here find that this is a place where they can do God’s work, as corny as that may sound.”

As integral as the Public Defender’s Office now is to the legal system, it was a radical notion when it began. It arose from decades of lobbying by Foltz, whose long list of accomplishments included being the first female lawyer in California. With fellow suffragettes and Progressive allies, she sought to balance the odds in the late 1800s against impoverished defendants who were often railroaded by ambitious prosecutors and judges, even though they were supposed to be presumed innocent.

At the time, the state prosecuted people suspected of criminal wrongdoing, but didn’t underwrite any of their defense costs. A judge could appoint a lawyer to represent a pauper. But the court-appointed attorney, who was duty-bound to take the assignment, had to work without pay, or pro bono.

As a result, few competent lawyers made themselves available for such work. Instead, judges typically drew from the lowest ranks of the courthouse pecking order, often strolling out into the hallways and grabbing whoever happened to be around.

Foltz was outraged by the situation. A lawyer’s daughter, she had turned to the law to support herself after her husband deserted her and their five children. She had a soft spot for the poor.

She also had a knack for agitation: When she learned that only white males could become lawyers in California, she hounded the governor into signing landmark legislation to abolish the inequality. When she couldn’t’ get into law school, she sued for admission. Now, pressed into action on behalf of poor clients, she believed the time had come for lawyers like her to be able to make a living.

So she began agitating for legal reforms that would guarantee a paid defense and balance the odds against the defendant. According to a definitive biography of Foltz by retired Stanford law professor Barbara Babcock, she spent three decades campaigning in state legislatures and drafting model statutes before a political tide of Progressives and women—who had just gotten the vote here—led to success in California.

By then, Foltz was working as a deputy district attorney in Los Angeles County, another first for a woman, and was an influential political voice, both nationally and here. In November 1912, Los Angeles County voters approved a charter that included the creation of the Office of the Public Defender, and the following year, it was ratified by the state legislature.

After a competitive exam, the Board of Supervisors appointed Walton J. Wood, a Los Angeles deputy city attorney, as the first public defender in the nation. The office opened on Jan. 9, 1914.

Over the years, according to Public Defender Brown, the office’s focus has changed with the societal landscape.

“In the past, we looked exclusively at winning—at getting the guy out and moving on,” he says. “The thought was that we’re lawyers, not social workers. But in fact, a good lawyer really is a kind of social worker. You end up getting involved with everything from housing to mental health needs.”

To that end, the office now works closely with social services in the county, from children’s services to mental health. It also has helped pioneer the use of specialized courts for addicts, veterans, the mentally ill and women, and has become involved in communities with programs like Parks After Dark.

And as it heads into its next century, he says, the department has added to its diversity in ways that would probably please the suffragette who made it happen: More than half of the lawyers—from trial lawyers to managers—are female now.

Clara Shortridge Foltz's groundbreaking activism led to the creation of L.A. County's Public Defender's Office in 1914, the first of its kind in the nation.

Posted 2/21/14

Audit raps sheriff fund management

January 16, 2014

L.A. County Auditor-Controller Wendy Watanabe at the Hall of Administration. Photo/Los Angeles Times

A new Los Angeles County audit has revealed that the Sheriff’s Department did not meet even the most basic—and required—accounting practices in its management of numerous special funds, which have accumulated $160 million with no written plans on how the money should be spent.

Some of the money has flowed into these Sheriff’s Department funds from various fees imposed on the public, including a slice of court fines and assessments on vehicle registrations, according to Auditor-Controller Wendy Watanabe.

In a review of three recent fiscal years, the Auditor-Controller’s office found that the department used only 57% of the $370 million that had built up in eight special funds, each of which is legally restricted to purposes ranging from drug investigations to vehicle theft programs to automated finger-printing systems. The California controller’s office requires that specific spending plans must exist for these growing pots of money.

“Excessive revenue indicates that the counties should reduce fees or establish reserve accounts,” auditors said.

The Sheriff’s Department did not dispute the findings, saying it would evaluate the special funds and determine “appropriate expenditure requirements and spending plans.”

But during a public briefing on the audit for Board of Supervisor staff members on Wednesday, Sheriff’s budget official Glen Dragovich downplayed the significance of the rising fund balances. “There’s a plan,” he said, “but it’s just not written down.” He said the department has taken a conservative approach to spending “because we want to make sure we have money for future years.”

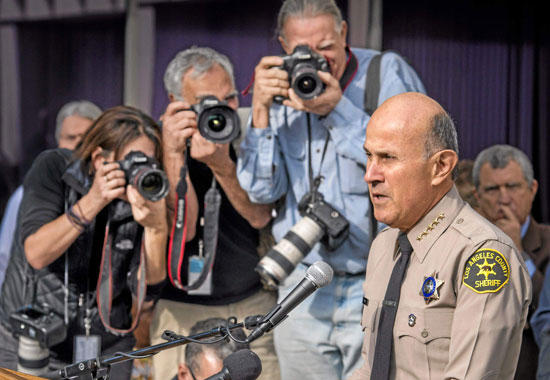

The audit is certain to raise new concerns about the department’s top-level management. It comes at a time when the agency already is confronting problems across its operations, including, most significantly, the recent indictments of 18 members of the force for alleged brutality, corruption and obstruction of justice. On January 7, Sheriff Lee Baca announced he would not seek re-election to a fifth term.

Beyond criticisms centering on the $160 million in unspent funds, auditors took the department to task for a variety of other violations of county fiscal policies involving management and oversight of special revenue and trust funds. Although there was no evidence of malfeasance, the department’s failure to comply with rigorous accounting measures increases the odds that public monies could be placed at risk, the audit suggested.

Among other things, the Sheriff’s Department breached government rules by transferring $1.6 million in unclaimed funds to its own operating budget rather than providing the money to the Treasurer and Tax Collector. That office is responsible for publishing a newspaper notification of the unclaimed funds. If no one comes forward—county inmates, for example, who’d surrendered their property at the time of booking—then the money should be placed in the county’s general fund.

“Transferring unclaimed funds to a department’s revenue,” the audit stated, “may result in the use of funds that were not authorized by the Board of Supervisors as part of a publicly accessible appropriations process.”

The Sheriff’s Department management said it was unaware of the requirements for unclaimed funds.

To read the full audit, click here.

After Baca, a new start

January 16, 2014

When Lee Baca announced his retirement from the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, I was relieved but not surprised. As a colleague and friend, I knew he was hurting.

While preparing to seek a fifth term as sheriff, Baca had become the public face of a department rocked by scandal, including the recent federal indictments of 18 members of his force for alleged brutality, corruption and obstruction of justice. With each passing day, as his campaign opponents honed their attacks, it wasn’t only the sheriff’s re-election prospects that were taking a hit but also the department to which he’d dedicated nearly 50 years of his life.

So Baca did the right thing—the courageous thing—for himself and the agency. His voice cracking, he told a packed news conference that he was stepping aside at the end of this month. “I don’t see myself as the future,” he said. “I see myself as part of the past.” Los Angeles County voters will now have a rare opportunity to elect a sheriff without an incumbent on the ballot.

Although Baca may have removed himself as the campaign’s lightning rod, he has presented those of us on the Board of Supervisors with a huge responsibility for the department’s uncertain future. It’s now our job to appoint an interim sheriff who’ll serve until December when the newly-elected sheriff is sworn in.

To be sure, conditions within the Los Angeles County jail system have improved since allegations of excessive deputy violence began escalating several years ago, leading to the creation of a citizen’s commission that blamed top management for many of the problems. By all accounts, the use of serious force is down significantly. Still, big challenges confront the department, including how to humanely—and constitutionally—deal with the thousands of inmates entrusted to our custody, especially those suffering from mental health problems.

In the days ahead, our interviews with candidates for the interim sheriff position will begin. And I can tell you this much for sure: We should not be putting a caretaker in charge. We need a reformer who’ll build on the momentum the department has achieved since the blue-ribbon Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence concluded its widely-praised work. We need a proven leader who can resist the potential bureaucratic backsliding that can occur in an institution where change comes hard.

And we need someone who won’t be entering the growing field of candidates competing for the top job. This historic moment of transition is too important for an interim sheriff to have his or her attention diverted by a tough campaign or to think it’s necessary to build political alliances within the department’s ranks.

An interim sheriff must give his elected successor every opportunity to hit the ground running to swiftly restore the department’s reputation and repair the morale of the thousands of hard-working men and women who’ve been unjustly tarnished.

Every crisis presents an opportunity. And the voters of Los Angeles County now have precisely that—an opportunity to put their imprint on the future of the Sheriff’s Department, casting a vote for leadership that can clean house and offer a new beginning.

Posted 1/16/14

Orange Line’s “dismal” fare findings

January 16, 2014

The Orange Line, shown at opening of the busway's extension, is popular but many aren't paying to ride.

Up to 22% percent of Orange Line passengers were deliberate fare evaders and as many as 9% “misused” their TAP cards, according to recent audits assessing the extent of fare-beating on the popular San Fernando Valley dedicated busway.

The findings, presented Wednesday to a Metro committee, are “rather dismal,” acknowledged Duane Martin, the agency’s deputy executive officer for project management.

“We understand there’s no glossing over the significant fare evasion,” Martin said, although he added that the recent redeployment of sheriff’s deputies to check fares along the line has improved the situation.

The Orange Line carries about 30,000 riders a day, and unlike the rest of Metro’s fleet, does not have fare boxes on its buses. Instead, it relies on patrons at un-gated stations to tap their fare cards at machines known as “stand alone validators.”

Many, it appears, have been taking advantage of the system to hitch a free ride.

Two audits—conducted December 3 and December 17—surveyed all patrons as they got off the bus at various Orange Line stations. The first audit, at the North Hollywood, Van Nuys and Sherman Way stations, found 22% fare evasion (traveling without a TAP card or using a card with no value on it) and 9% TAP card misuse (having a valid TAP card but, perhaps inadvertently, failing to properly tap it before entering the bus.) The second audit, at the North Hollywood, Reseda and Canoga stations, found 16% fare evasion and 8% TAP card misuse.

The audits were prompted by a November, 2013, motion by Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, a member of Metro’s Board of Directors and a longtime proponent of reforms to help eliminate free riders on the Los Angeles transit system. In a major milestone, gates on the L.A. subway, which for years had operated on the honor system, were finally latched last year. But locking down Metro’s light rail system and the Orange Line, which operates in a similar fashion, is still a challenge.

On Wednesday, Yaroslavsky and another director, Los Angeles City Councilman Paul Krekorian, responded to the Orange Line audit findings with another motion, this one directing Metro staff to explore installing gates at the busway’s stations. They also said that signs explaining that tapping is mandatory (and listing fines for failing to do so) should be placed on or beside the ticket validating machines at the stations.

Moreover, they asked for status reports on gate installation for projects currently being constructed or designed, including phase two of the Expo Line, the Foothill extension of the Gold Line, and the Crenshaw Line.

“Unless we take this issue head-on, and begin to design stations with gates…fare evasion will continue to skyrocket and become a perpetual problem with no end in sight,” the motion said.

“Saturating” the Orange Line with sheriff’s deputies checking fare cards has already started having an impact, including in the period between the first and second audit, Metro deputy executive officer Martin said.

“The deputies are out there so people started tapping again,” he said.

Before Martin reports back to Metro’s board members on the issue in March, he plans to conduct another Orange Line audit, probably next month.

Wiping out all fare evasion is unrealistic, he said, but there is lots of room for improvement. “I would love to be able to operate the system with plus or minus 2% or 3% fare evasion,” Martin said. “That’s the goal.”

Posted 1/16/14

Game on for Bruin, Trojan fare cards

January 15, 2014

The UCLA Bruins and USC Trojans are archrivals on the gridiron, but fans share a common interest: getting to the game in time for kickoff.

To that end, Metro Board members Zev Yaroslavsky (UCLA, Class of ‘71) and Ara Najarian (USC, Class of ‘85) have teamed up on a motion to have the agency develop specially branded Bruin and Trojan TAP cards for travel to home games during the 2014 football season.

There are good light rail alternatives for getting to both teams’ home stadiums; the Expo Line transports USC fans to the Coliseum, and the Gold Line is a shuttle ride away from Pasadena’s Rose Bowl, where the Bruins play. But getting on the train—especially if you don’t already have a TAP card loaded with funds to pay the fare—can cut into the convenience of leaving the driving to Metro.

“Often there are long queues to buy TAP cards and get onto the platform,” the motion said.

Enabling fans to buy a preloaded TAP card at the same time they order tickets through their respective university would “make the whole experience not only more enjoyable, but convenient, efficient and hassle-free,” the motion said.

On Wednesday, Metro’s Finance and Budget committee moved the motion forward to the transit agency’s full board for consideration.

Posted 1/15/14

The 80-hour Jamzilla on the 405

January 14, 2014

Officials are urging motorists to stay away from the 405 construction zone on Presidents' Day weekend.

When you’ve been through two Carmageddons, three bridge reconstructions and untold thousands of construction hours, what’s an 80-hour closure on the 405 Project?

It’s Jamzilla—and before you start making any Valentine’s Day evening or Presidents’ Day weekend plans, best take a look at Metro’s upcoming closures of northbound lanes on the 405 Freeway through the Sepulveda Pass.

Three northbound lanes on the 405 will be closed during the daytime hours over the long weekend of February 14-18, and the entire northbound freeway will be closed for overnight work. The connecting ramps to and from the 10 Freeway will be closed as well. Details for Jamzilla are here.

“We’ve named it that because of its potential to create monstrous congestion,” said Diane DuBois, chair of Metro’s Board of Directors, who was among the officials who announced the closure on Tuesday and urged motorists to stay away from the area that weekend.

The closures will allow construction workers to excavate and repave portions of a new, 10-mile northbound carpool lane, one of the primary benefits of the $1 billion-plus project now entering its fifth and final year.

The 80-hour Presidents’ Day weekend closure represents a consolidation of several 55-hour closures that had been planned.

“This closure operation will save significant time and minimize future closure impacts to the community and traveling public,” Metro said in a news release.

Jamzilla may be big, but it’s not the only closure on the horizon. This Thursday, January 16, the southbound 405 will be closed from Valley Vista Boulevard to the southbound Skirball Center Drive on-ramp from midnight to 2 a.m. The northbound freeway then closes from 2:30 a.m. to 5 a.m. from Getty Center Drive to the northbound Skirball Center Drive on-ramp. The closures are needed so that construction workers can pour the deck of the Skirball Bridge, which also will be completely closed from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. More information is here.

Then, on the night of January 18, the southbound freeway will be closed from the 101 Freeway to Getty Center Drive. It’s set to reopen the morning of January 19. Click here for details.

The 405 project is expected to be “substantially completed” by mid-year, meaning that the carpool lane and ramps will be open. Final completion is scheduled by the end of 2014.

Posted 1/14/14

Here’s the skinny for 2014

January 9, 2014

Make eating out less hazardous to your waistline by looking for the "Choose Health L.A. Restaurant" sign.

As January unfolds and New Year’s resolutions remain firm, county Public Health officials are offering this reminder: Just say less.

A smaller-portion initiative launched last fall has resulted in hundreds of decals—similar to those issued with the department’s popular letter-grading program—being placed in restaurant windows county-wide. The signs, designating a “Choose Health L.A. Restaurant,” mean that reduced-size options and other healthy choices, especially for kids, are on the menu.

The 800-pound sandwich in the group, so to speak, is Subway, with 640 locations taking part. Italian and Mexican restaurants are also represented, along with L.A. standards like Barney’s Beanery, whose four outlets have signed up.

But there are still challenges, including the recruitment of Asian restaurants.

Scott Chan, program director for the Asian and Pacific Islander Obesity Prevention Alliance, said his group is working with the county on outreach.

“We are still in the beginning stages, and most of the Asian owners we have talked to do not know about the program. I am hopeful as the campaign continues that we will be able to reach these folks,” Chan said in an email. “We truly believe that increased language access with these owners, whether through translated forms or in-person interpretation, will guarantee greater success and healthier communities.”

Public Health’s Linda Aragon said her department has sent letters about the program to 27,000 restaurants in the county, and is also trying to spread the word via its network of restaurant inspectors, who are on the frontlines of local eateries every day.

As for consumers, there seems to be a healthy amount of interest.

“We looked at Google Analytics, and we’ve gotten more than 60,000 page views since October,” Aragon said.

It’s important to keep promoting the program, Aragon said, adding that a formal evaluation of how it’s working is expected in the year ahead.

Meanwhile, Aragon said, resolving to take even small steps toward healthier habits can make a big difference. (Some tips to get started are on the Choose Health L.A. website.)

“We always think it’s a good thing when folks consider starting out the New Year by eating better, starting to exercise, or even quitting smoking,” Aragon said. “Anything we can do to improve people’s lives, and this is a great time to start it.”

Posted 1/9/14

Heroes in hardhats

January 8, 2014

They have rescued small children from oncoming traffic. They have brought a victim of attempted murder back from the brink of death. They have braved rising floodwaters and raging house fires. Last month, they dragged an unconscious driver from a burning SUV seconds before the truck’s gas tank exploded.

Not all first responders are sheriff’s deputies or firefighters. Some also find themselves in the occasional life-and-death situation while minding the county’s infrastructure at the Department of Public Works.

Emergency response has been among DPW’s core services since 1985 when the department was created, though the public tends to be more familiar with the department’s work in engineering, flood control and road maintenance. DPW maintains a 24-hour emergency operations center, and employees there are trained for disaster.

In fact, over the years, so many DPW hardhats have stepped into the breach so often that after a beloved employee named Kelly Bolor died in Iraq in 2003 while serving as a member of the U.S. Army Reserves in Mosul, the department created an in-house award for valor that has been presented in the wake of a number of incidents.

Since that date, nearly two dozen DPW employees have received the Kelly Bolor Award for heroism of one sort or another, from Ignacio Orozco Jr., who used a county dump truck to head off a potentially fatal car crash on Imperial Highway last year to members of Road Maintenance Division Crew 551, who extinguished a raging house fire in 2011 near their Antelope Valley work site, to Gary Clinton, who used his motorgrader to rescue panicked motorists from a flooded crossing in the high desert in 2005.

“I’ve been with the county for 29 years, and I think we’ve all at one time or another been first responders in some kind of situation,” says Steven Smith, a road maintenance superintendent in Agoura whose crew members, Lowell Johanknecht and Enrique Ramos, are expected to be nominated this year for pulling a woman from a burning SUV on Mulholland Highway on September 18.

Lowell Johanknecht, left, and Enrique Ramos are the latest Public Works heroes. Photo/ Christian Garcia DPW

“If an accident happens and you’re around, you rise to the occasion. This job can be dangerous, too.”

That certainly was the case for the award’s first recipient, Marco Andonaegui, who was replacing traffic signs in 2004 on Topanga Canyon Boulevard near the 101

Freeway when he glanced up and saw a child tumble out of an SUV.

“He was 8 years old and his buckle must have come undone,” says Andonaegui, a 30-year DPW employee who says he still gets chills when he thinks of how close the child came to being hit by oncoming traffic.

“I was alone, going the opposite direction and they were just a couple a cars in front of me.”

Andonaegui scrambled out of his county vehicle, jumped the median and grabbed the child as the SUV drove on, the child’s mother oblivious to what had happened.

“Cars were swerving around us, braking around us, the little boy was crying and crying,” recalls Andonaegui. “I don’t know how the heck I didn’t get hit, let alone the little kid.”

Fifteen minutes later, he says, the mother circled back, frantic.

“She was desperate and grateful, and she must have given me 20 or 30 thank yous, but she was crying so hard, she forgot to ask for my name or give me hers,” he remembers.

It was only afterward, he says, that he learned she had written down the phone number on the back of his county truck and called the department. A father of grown children, he says he never heard from the woman again and still doesn’t know her name or her son’s name, but he still keeps his award plaque in his Lynwood living room.

Dam Operator Gary Elrod says he and his fellow crewmen on the remote San Gabriel Dam compound likewise never heard again from the young man they rescued.

It was early on a Tuesday morning, May 29, 2007, and the seven dam workers, several of whom live on the isolated site high in the San Gabriel Mountains, were starting their day early when Assistant Dam Operator Benny Velasco spotted a body in a drain near the roadside.

“It looked like he’d been attacked at another location, stuffed in the trunk of his car, driven to the entrance area of the San Gabriel Dam in Azusa Canyon and left there for dead,” recalls Elrod. “I personally counted nine stab wounds.”

A 25-year DPW employee who had worked in his youth with an emergency response team in Saudi Arabia, Elrod says he grabbed his blanket and safety gear and started to administer first aid.

As the crew waited for paramedics to arrive, Elrod tried to keep the barely coherent victim from falling into unconsciousness.

“This isn’t your time,” he remembers repeating to the young man as the sun rose over the mountains. In the hospital, Elrod says, the victim, who was from Whittier, refused to name his attacker, and the case was still unsolved three months later when he stopped asking about it.

“He denied everything he’d said to me when the sheriff questioned him later,” says Elrod. “All I know is, he’s out there somewhere with a horror story to tell his children and he’s lucky we came along when we did.”

The workers say they don’t mind that the recipients of their help often have no idea who they are or what department they work for.

“It makes you feel good just to be able to help,” says Johanknecht, the 23-year-old road laborer who pulled the woman from the burning truck last month on Mulholland Highway near Las Virgenes Road.

Johanknecht, who lives in Redondo Beach, says he had finished his shift at the Road Maintenance Division’s Yard 339 near Agoura Hills and was heading off to meet his girlfriend at their community college when he noticed the plume of smoke and the overturned Chevrolet Suburban. Pulling over on his motorcycle, he called 911 and ran toward the crash site.

“The 911 operator asked if anyone was in the car, and I said yeah, there’s a lady in the driver’s seat,” he remembers. “Right then, an older gentleman on a bicycle came up the hill and said, ‘What do you want to do?’ And I said, ‘Get her out!’”

Just then, he says, Ramos pulled over, having seen the skid marks, the smoke and his coworker’s abandoned Suzuki DR650. Working together, the three wrestled the woman, who appeared to be in her 40s, out of the black SUV and back toward the road’s shoulder.

“She was panicked and freaking out and pushing us away and in shock,” Johanknecht says, “and smoke was engulfing the car and all the air bags had deployed and blocked all the windows.”

As they carried the woman to safety, the SUV’s gas tank exploded, igniting a brushfire that engulfed nearly two acres before two Super Scoopers and four water-dropping helicopters were called in to contain it. Los Angeles County Fire Inspector Scott Miller could not release the woman’s name, but said she was transported to a local hospital. Ramos and Johanknecht say they never found out who she was and haven’t heard from her.

Johanknecht says his parents and girlfriend were “worried and proud at the same time” when they heard what happened, and wishes the crash victim—whoever she is—a speedy recovery.

“You never expect this, but you never know—we work out here in no man’s land, and a lot of things happen,” he says. “I just hope that someone would do me the same favor if something like that ever happens to me.”

Posted 10/15/13

Board votes to restore cross to seal

January 8, 2014

The current county seal, revised in 2004, will be changed again to include a cross atop the mission.

Reopening a long-running and divisive controversy, the Board of Supervisors this week voted to once again place a cross on the Los Angeles County seal.

The action came nearly a decade after the board agreed to remove the Christian symbol under threat of a legal challenge by the American Civil Liberties Union. The county spent hundreds of thousands of dollars after that 2004 decision to replace the seal with a redesigned version that now appears throughout its facilities and on items ranging from business cards and badges to uniforms and vehicles.

The impetus for the board’s about-face this week was a motion by Supervisors Michael D. Antonovich and Don Knabe, who argued that the current seal’s depiction of the San Gabriel Mission without a cross is “artistically and architecturally inaccurate.” Although the cross was removed from the mission during retrofitting following the Whittier Narrows earthquake, their motion said, it has since been restored to the structure and the county seal should reflect that.

Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas joined Antonovich and Knabe in voting to bring back the cross. Supervisors Gloria Molina and Zev Yaroslavsky voted against the measure.

Although the motion made no mention of religion, Yaroslavsky said the cross is the principal symbol of one particular faith, and noted that there is extensive legal precedent barring its incorporation into the seal on Constitutional grounds.

“The court cases have made it very clear that the use of a symbol, the principal symbol of any religion on a government seal, is unconstitutional,” Yaroslavsky said.

“And this is not just about history,” he added. “It’s about the cross. To say anything different would be really somewhat disingenuous…There are a hundred ways we could depict history. But the one that’s been chosen here is the cross.”

The county seal currently in use replaced a 1957 version designed by the late Supervisor Kenneth Hahn and drawn by the artist Millard Sheets. Hahn said at the time that the seal was intended to depict “the cultural and educational and the religious life of this county.” Featured on the seal, in addition to the cross, were images including the Hollywood Bowl, a Spanish galleon, a tuna, a prize-winning Guernsey cow named Pearlette, several oil derricks and the goddess Pomona carrying fruit. The redesigned seal eliminated the cross, the derricks and the goddess but added an image of a mission (without a cross) and a Native American woman.

The 2004 decision to drop the cross prompted an uproar, with nearly 1,000 people gathering outside the Hall of Administration on the day of the Board of Supervisors’ vote, some with signs calling the ACLU the “Annihilation of Christian Liberties Union.” Hahn’s children, then-Mayor James Hahn and then-Councilwoman Janice Hahn, argued in favor of keeping the symbol on the county seal.

Yaroslavsky, however, said at the time he was willing to make an unpopular decision if it was the right thing to do: “The First Amendment is not a popularity contest.”

At Tuesday’s meeting, he once again argued against including a religious symbol on a government seal, but this time was on the losing end of the vote. Before the board’s 3-2 decision, Yaroslavsky predicted the county would face, and lose, a legal challenge—particularly since it would be restoring a symbol it had removed after questions were raised about its constitutionality.

That point was echoed by Peter J. Eliasberg, legal director of the ACLU of Southern California, who said reincorporating the cross into the county seal would violate both state and U.S. constitutions. He also said that the separation of church and state has helped to strengthen religious activity in the United States, not to diminish it.

“The ACLU strongly believes that religion has flourished in this country, perhaps more than any other, and religious pluralism has flourished because the government does not favor or denigrate any particular religion,” he said. “Adding a sectarian religious symbol to the county seal, the preeminent symbol of one particular religion, runs against that grain.”

After the meeting, Eliasberg would not say whether his organization plans to file a lawsuit.

While Eliasberg spoke against the motion, several others supported it, including a resident of Altadena who said: “There’s nothing unconstitutional about having an historical reference to the role of religion in the formation of the nation…None of this has really anything to do with the Board of Supervisors or anyone else promoting religion. We’re just accurately depicting our cultural heritage in history.”

Posted 1/8/14

Check for the latest closure information

Check for the latest closure information