Around the County

Saving animals by the numbers

January 23, 2014

Better data can lead to programs to save the lives of kittens, like this one in a new Mission Hills “nursery.”

Furry pet faces never fail to tug heartstrings, but when it comes to animal welfare, numbers don’t lie: Last year, some 79,150 cats, dogs and other pets ended up in Los Angeles County animal shelters, and fewer than half of them made it out alive.

That, believe it or not, is actually good news. Five years ago, the euthanasia rate in county shelters was 65%. But while most people know that pet adoptions and spaying, neutering and licensing are all acts of kindness, nothing drives home the point like the hard facts.

That’s why the county Department of Animal Care and Control has gone online with its statistics.

“Our biggest hope is that people will see these numbers and realize not only that the department is doing great work, but also that this really is serious. Spaying and neutering and keeping pets secured so they don’t end up in shelters is really important,” says Betsey Webster, chief deputy director of Animal Care and Control for the county.

“These animals end up with us as a result of human behavior. Some people just don’t understand, but some of it also is just irresponsible ownership.”

Department Director Marcia Mayeda says the new stats pages, which went up in late December, were on her to-do list for a long time, but couldn’t be implemented until the department upgraded its 13-year-old web site. Though animal control data have always been a matter of public record, until now, people had to call or email the department and request them.

“Other agencies put their statistics online, but we wanted to do more than just put up spreadsheets,” says Mayeda. Working with the county’s Internal Services Department, her team spent about six months turning its raw numbers into colorful graphics and pie charts that demonstrate the scope and the challenges of animal welfare in the county.

For instance, Mayeda offers this disturbing data point: Only a quarter of the nearly 30,000 cats that ended up in county shelters last year escaped euthanasia, and only one in 100 was returned to an owner.

“The No. 1 reason why an animal dies in our shelters,” she says, “is because it’s a feral cat.”

For dogs, on the other hand, the picture is much more optimistic. Only about 35% of the county’s 41,500-plus shelter canines had to be euthanized last year.

“When I started in 2001, our euthanasia rate for dogs was about 66%,” says Mayeda, noting that 60% is still the national average. “But we’ve made tremendous inroads. We’ve worked closely with more than 200 animal rescue groups. We do pet transport, where groups will take 30 or 40 dogs at a time to other parts of the country where there’s a demand for adoption.

“And we’ve gotten a lot more volunteers in the last 10 or 12 years, who have helped us with finding pets homes through offsite adoptions. A lot of people don’t want to go to shelters because they’re afraid it’ll be too sad for them, so we’ll take 10 or 20 dogs to a PetSmart, and people will come and adopt them. All of it has really pulled down our euthanasia rate.”

Marc Peralta, executive director of the Best Friends Animal Society in Los Angeles, which has worked with the City of Los Angeles to reduce the kill rates of healthy, treatable animals in its shelters, applauded the county’s efforts. Good animal control data, he says, can literally mean the difference between life and death for lost, abandoned or homeless pets.

Though some shelter animals will inevitably be put to sleep—vicious dogs, for example, or pets who are too old, ill or feral to be feasibly adopted—many end up being euthanized merely because public shelters have limited space but are forbidden by law to turn any stray away.

“In Los Angeles’s city shelters, one of the first things we noticed was that something like 6,000 of 13,000 cat euthanasias were neonatal kittens,” says Peralta. The baby cats were too young to be spayed or adopted, he recalls, but the city shelters weren’t equipped to provide intensive bottle-feeding to that many kittens without badly neglecting their other charges.

So last year in Mission Hills, Best Friends and the No Kill Los Angeles animal welfare coalition jointly opened a neonatal kitten nursery.

“We thought, if we can get those newborns to two months, who doesn’t want to adopt kittens?” That initiative alone, he says, has saved thousands of cats from euthanasia. “All that was based on data from shelters,” he says. “It helps us know where to point the guns.”

Mayeda says the department is hoping over time to deepen their online statistics, which currently focus on overviews and shelter-by-shelter outcomes in the county’s six regional shelters. Those numbers in themselves are eye-opening—pets in the county’s Agoura shelter, for instance, are about twice as likely to be adopted or returned to their owners as are pets in the much-larger Downey shelter.

But Mayeda says she also wants to drill down on the feral cat outcomes so that the public better understands the urgency of the problem.

“A lot of people will say, ‘There’s this cat in my yard and I don’t mind putting out food, but she keeps having kittens and they get hit by cars or beaten up by tomcats.’ Well those people mostly don’t want to spend $300 to take that cat to a veterinarian and have it spayed, but a feral cat is like a raccoon—you can’t really adopt it.”

In fact, she notes, the county offers discounted services for senior and low-income pet owners, and animal welfare groups such as the Spay Neuter Project of Los Angeles will spay or neuter a “community cat,” as they call feral felines, for as little as $25. But many people are unaware of those services and believe that a trip to a vet is the only option.

“So people end up bringing it to the shelter, where our only option is to euthanize it. But if they were to see the numbers, and if there were, say, a big push for free or low-cost spaying and neutering and a program they could go to, well, that would be one less cat that we’d have to put to sleep.”

In the meantime, Webster and Mayeda say, pet owners can take advantage of the vaccination, licensing and microchipping services offered at shelters countywide. Currently offered on various weekdays at the shelters, the services will gradually shift this year to alternate Sundays from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. (Click here for the current microchipping schedule, and here for information on the new Sunday clinics.)

“Microchipping is mandatory in unincorporated Los Angeles County,” Webster points out. “But it’s also great because an animal that is microchipped can make it home without entering the shelter at all.”

Posted 1/8/14

Code busters beware

October 29, 2013

Dusan Pavlovic is making a real nuisance of himself.

As a member of the Los Angeles County Counsel’s office, it’s his singular mission to make life difficult for people who violate Los Angeles County’s public nuisance codes for everything from operating neighborhood drug houses to building structures without permits to running raves in warehouses rented under false pretenses.

Then there’s the downright creepy.

“We found one house that had concrete prison-style cells underneath,” Deputy County Counsel Pavlovic recalled. “The owner said he constructed it as a bomb shelter but the Sheriff’s Department suspected it may have been used to keep undocumented immigrants.”

On Tuesday, the Board of Supervisors gave Pavlovic and his small code-enforcement unit a much-needed boost in their “nuisance abatement” efforts for Los Angeles County’s unincorporated areas: a new ordinance that, for the first time, allows the county to collect daily fines, attorney’s fees and administrative costs.

“When you hit them in the pocket book, that’s where it hurts,” Pavlovic said. “They’re more attentive to the problem.”

Pavlovic, who has led the enforcement team since its creation eight years ago, said the existing public nuisance law needed toughening because violators had little to fear, given the unlikelihood of judges giving jail time for most code transgressions.

“You’d be surprised how many times people choose to ignore the issue,” explained Pavlovic, who pushed hard for the stiffer penalties. “They tell us, ‘Do what you want.’ Now we will.”

The ordinance, which has been on the books for decades, bans property uses that are “detrimental to the community’s tranquility and security.” Those include activities that, according to the law, “endanger public health, safety and welfare, invite crime, reduce property values, degrade the environment and negatively impact the quality of life of the residents.”

Pavlovic said he’s seen—and heard—it all out there since joining the county counsel’s office in 2005. “I tell you, these people get pretty creative,” he said.

For example, there was a property owner in Topanga Canyon, who, for reasons that remain unclear, perched an automobile on the roof of his carport. Rather than remove the vehicle as ordered by the county, the violator, according to Pavlovic, “just took a couple of plywood boards and enclosed the car so it was no longer visible. He said, ‘You see, it’s no longer there.”

Some violators, on the other hand, are so open about their entrepreneurial misdeeds that they practically invite neighbors to drop a dime on them. Take the case of an East Compton man who was running an illegal “chop shop” at his home. Pavlovic said the man not only was dismantling cars but was then selling parts in the front yard.

“Residents kept complaining, and he kept dismantling,” Pavlovic said.

Pavlovic said he doesn’t want to sound like a cliché but that he’s committed to “improving the quality of our neighborhoods and eliminating these public nuisances.”

“We’ve all been in situations where we’ve had a bad neighbor,” he added. “I think that’s something every person can relate to.”

Posted 10/29/13

Rising river lifts neighborhood, too

September 6, 2013

Chief Ranger Fernando Gomez orchestrates a "community paddle." Photos/Grove Pashley, LA River Kayak Safari

It was still weeks before kayakers would start journeying down a lush stretch of the Los Angeles River, but boosters of the summer-long pilot program could feel the resentment building.

Residents of Elysian Valley were worried that interlopers would start flocking to—and disrespecting—their diverse, working-class neighborhood along the river. Some wary families were still nursing hurts going back generations, when people were relocated to “Frogtown” after being forced from nearby Chavez Ravine to make way for the Brooklyn Dodgers’ new home.

“There are some long memories out there,” said artist Steven Appleton, chairman of the Elysian Valley Riverside Neighborhood Council and an advocate of the escalating efforts to remake the L.A. River. “A perception was developing that a lot of people from outside the area were going to take advantage of them.”

So Appleton donned another hat. He and his partner, Grove Pashley, quickly created a kayak company and began working with the Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority to build a local constituency for the new Los Angeles River Recreation Zone—a brief, closely-watched collaboration that ended on Labor Day but is winning praise as a model of neighborhood engagement for the future.

News coverage of the pilot program has mostly focused on the strange yet appealing sight of 3,000-plus kayakers who, between Memorial Day and last Monday, worked their way down a 2.5-mile section of the river in the Glendale Narrows area. There, the bottom is coated in silt and rocks, unlike other sections of the 51-mile route, where concrete is the dominant feature. Paddlers included everyone from Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti and County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky to veteran thrill seekers and upstart adventurers.

But what’s proven especially gratifying to organizers is the less heralded success of their strategy to get buy-in from Elysian Valley residents.

“We told them, ‘We want you to feel comfortable. We’re not excluding you. We’re including you. ’ It was my job to make sure they felt comfortable and welcomed,” said MRCA Chief Ranger Fernando Gomez.

Among other things, Gomez said, the MRCA, which managed the project on behalf of the City of Los Angeles, increased the number of rangers in the area and told them to enforce such park rules as no overnight camping, drinking or smoking. This quickly gave residents a heightened sense of security in a neighborhood with an engrained gang history. At night, Gomez said, he saw entire families—including a pregnant mom, her husband, son and family dog—walking along the riverbank’s bike path.

“That’s something I never would have seen 10 or 15 years ago. Back then, if people were out, they were up to no good,” said Gomez, who patrolled the area as a rookie ranger. “These families have stepped up and said: ‘This is our backyard.’ ”

Another turning point came when Appleton’s company started to organize “community paddle” evenings for locals, many of whom couldn’t afford the kayak tours ranging in price from $55 to $65, offered by Appleton and a competing company. In all, there were three events, which took place between 4 p.m. and 7 p.m. The final one drew a crowd of 70 residents.

Appleton said one of his best memories of those evenings was of a woman who’d lived along the river her entire life but had never ventured into the water, not even as a kid. “It was on her bucket list,” Appleton said. Although she tumbled five times into the calm and shallow waters in front of Marsh Park, she was having such a good time that, unlike other residents, she wouldn’t relinquish her boat.

“It was occupied the entire three hours,” Appleton recalled admiringly. “She just wouldn’t get out.”

“Initially people in the community were skeptical” of the recreation zone, said Appleton, who began canoeing as a youngster in Michigan. “But those events really helped turn things around.”

Ranger Gomez was more effusive: “The community was ecstatic about it.”

Come next summer, river advocates hope the Glendale Narrows recreation zone will be back and embraced by the community—along with some changes for the next wave of kayakers.

Among other things, Gomez said, it would be helpful to have a second exit along the 2.5 mile zone so novice kayakers, weary from paddling or navigating rocks, can get out sooner. What’s more, he said he’d recommend removing some rocks in difficult passages to create “a little alley or lane that doesn’t alter the river in any shape or form” so frustrated kayakers don’t have to work so hard. “For a quarter of a mile, I don’t think the world would end downstream.”

Like Appleton, the ranger of 20 years has a memory that he also says he’ll treasure of the recreation zone’s inaugural season. His is of a young boy, around 12, who works as a “junior ranger” and is always quiet— “just a follower,” in the words of one MRCA colleague.

The youngster was the last down to the water. When he got into the boat, Gomez said, “he clenched his teeth and was literally started shaking with fear. I said, ‘Hi Buddy. I’m going to help you out. I’m going to teach you how to paddle—right, left, right, left. Not only did he learn about the river, he learned the skill of kayaking. By the end of the trip, he was racing other kids.”

Gomez paused at the memory. “I’m getting chills thinking about it,” he said.

Elysian Valley activist and entrepreneur Steven Appleton takes some neighborhood youngsters for a paddle.

Posted 9/6/13

Where summer lingers after Labor Day

August 29, 2013

Lance Wichmann says he finds serenity on the Santa Monica sand when the crowds disappear in September.

Lance Wichmann’s playpen was a patch of warm sand at the foot of Ocean Park Boulevard. His family’s Santa Monica house was less than a block from the beach, and his mom started carrying him there before he could walk.

Today, more than seven decades later, you can still find Wichmann at that same spot, sunning himself in retirement, a few tentative steps from the shoreline home that remains in the family. He knows just about everything there is to know about beach life around lifeguard station 26, which draws some of the heaviest crowds in Southern California during June, July and August.

And one of the things Wichmann knows (besides the best body-surfing breaks) is this: although Labor Day on Monday represents the unofficial end of summer, it’s the beginning of a two-month-long, locals-only holiday, when ideal conditions come to the beach—but not the people. The truth is that, unlike other coastal areas throughout the nation, air and sea temperatures here drop an average of only a few degrees between Labor Day and Halloween.

“It’s so much quieter,” the 72-year-old former insurance executive said of LA.’s extended summer season of September and October. “I know Santa Monica is a tourist town, but I like it when I can come down here at low tide, when the kids are back in school, and walk along the sand by myself. To me, it’s spiritual.”

Let the rest of the country use Labor Day as its farewell to summer. Here in L.A., savvy beachgoers know that the occasion actually signals “the start of the beach season,” joked county lifeguard Captain Kyle Daniels, who oversees community services and youth programs. In September and October, he says, “the days are warmer, the winds are lighter and the views of Catalina are better.”

And the crowds are so much thinner that, after Labor Day, lifeguard stations are staffed every mile or more, rather than every 200 yards. “I don’t want to say it’s easy,” Daniels said of the workload that comes with reduced staffing levels. “But it’s less intense.”

There are other signs in the bureaucracy that, come this weekend, vacationers are about to vanish.

Carol Baker, a spokesperson for the Department of Beaches and Harbors, offered this post-Labor Day tidbit: the agency’s facilities and property maintenance division, which oversees beach restrooms, has just received its last major order of toilet paper and expects to use only 400 cases during the winter months, compared to as many as 1,000 cases during the summer.

When asked about her own favorite beach month, Baker declined to pick a favorite. “I know this will sound like a bubbly cheerleader, but every month at the beach is my favorite.” That said, she acknowledged that “some of the best summer days are in the fall.”

And that may be particularly true this year because of the fog that has shrouded the coastline during August—or, as Baker calls it, “Fogust.” This week saw some of the best weather of the summer, with the weekday visitor count already way down.

“In July, you could barely see the sand, there were so many people,” lifeguard Chris Smith said on a brilliant Tuesday afternoon as he kept watch over a couple of body boarders and surfers not far from where Wichmann was working on his tan. “The crowd is non-existent right now.”

“It’s a secret,” he added, “that the beach season is still going strong in October.”

Up along the bike path, meanwhile, business was slow enough at Perry’s café that chef Robin Hathaway could take a break to talk to a visitor about the post-Labor Day rhythms. “All the locals come down to reclaim their spots,” Hathaway said. “People have their routines. It’s more health and fitness oriented—running, riding, yoga, skate boarding, surfing.”

Of course, if the café had its way, she said with a wink, “summer would last forever.”

Posted 8/29/13

Where CBS blackout hits home

August 14, 2013

In the weeks since Time Warner Cable and CBS began feuding, Leadora Sutton has been having technical difficulties in her daily life.

“My main show is ’60 Minutes’ and I miss it terribly,” complains Sutton, 84, whose Westside senior apartment house—like much of Los Angeles—is served by Time Warner. “And I can’t get ‘Family Feud’, which I like to watch at 6 o’clock as I eat dinner. It’s a silly show, but I relax with it. And now it’s gone because we can’t get Channel 9.”

Sutton isn’t the only cable customer who wishes her regularly scheduled programming would resume already. As the ongoing contract dispute between the two media behemoths entered its third week and federal officials fired off letters urging the companies to settle their differences, some 3 million customers this week remained caught in the middle of the argument over their distribution deal.

Lots of folks are annoyed, but nowhere is the aggravation more pronounced than among seniors, who’ve long been the network’s most loyal fans. Their screen-happy kids and grandkids may not miss it so much, what with their binge-watching back episodes of “Breaking Bad” on Netflix, or getting their comedy fix via YouTube on their phones. But for this crowd, losing CBS—with the most mature audience of the four major networks and an average viewer age of almost 57—is like losing an old friend.

“TV is an amazing issue with seniors,” says Doug Cope, director of operations for the Menorah Housing Foundation, which oversees 18 low-income apartment buildings for seniors throughout Los Angeles County, including Sutton’s. “If people start missing their programs,” he says, “you hear from them.”

Since August 2, Time Warner has been blocking out CBS in a standoff over how much the cable giant will pay the network to carry CBS-owned stations in Los Angeles, New York and Dallas. For subscribers here, that has meant not only the absence of popular shows such as “60 Minutes”, “NCIS” and “The Big Bang Theory,” but also the blackout of CBS-owned stations such as Showtime and KCAL Channel 9, which—crucially, in this winning season—airs the Los Angeles Dodgers.

“It’s not a life-or-death thing for the people I’ve heard from,” jokes Robert Miret, manager of the Zev Yaroslavsky Apartments where Sutton lives near Westwood. But, he notes, he is part of another contingent that is increasingly resenting the blackout—sports fans. “So for me . . . “

Miret was among thousands this month who missed the Dodgers game against the St. Louis Cardinals because KCAL was dark on his home television. The blackout continued this week as the Dodgers played the New York Mets—again, only for non-Time Warner viewers. And, Miret notes, football season is about to begin.

For his tenants, however, the irritation has more to do with the interruption of daily habits. Though the complex also offers satellite dish and basic antenna hookups, many of the tenants have chosen the option they’re most used to, which is cable. And, he notes, many can’t switch because the basic antenna hookup is only for high-definition TV, and most of the tenants own older models.

So they’re stuck, he says, and even those who own computers don’t see television the way their grandchildren see it, as just one screen among many. For their generation, and even for many of their children, TV is also a marker of time and a companion. And retirees tend to watch a lot of it.

“Sometimes I’m not out of the house until three or four in the afternoon, now that I’m not working, and as I’m making lunch, I like to watch the shows,” says 67-year-old Sandy Tenenbaum. “I watch ‘The Talk’, which is very interesting. I watch ‘The Doctors’, which is a very informative and educational. I watch ‘Dr. Phil.’ At seven o’clock I watch that ‘Insider’ gossip show with the celebrities.”

Sutton, whose TV now displays Time Warner’s negotiating position when she turns to her favorite channel, says she is making do with other shows while her cable company and her favorite network do battle.

“They’ll fight it out and it’ll be settled in a few weeks,” she predicts. (Meanwhile, CBS has stayed on top of its rivals in the ratings, blackout notwithstanding.)

But without her shows to divert her, Sutton says, she made a call the other day to Time Warner, and came away with an interesting tidbit—confirmed this week by sales representatives at the company’s online support center.

“Did you know,” she asks, “that I can get discounts on my utility bills, my phone bills, even my movie tickets, but my cable company doesn’t give a break to senior citizens?”

Bob Miret’s fingers are crossed that the blackout will be over in time for football season, in a few weeks.

Posted 8/14/13

Grand patriotism for Independence Day

June 27, 2013

Workers this week were busy sprucing up downtown's Grand Park for its inaugural 4th of July celebration.

Surrounded by iconic government buildings and carefully planted with diverse flora from around the world, downtown Los Angeles’ Grand Park isn’t the ideal place for the fiery explosions typical of big Independence Day events. So park staff had to get creative for the upcoming 4th of July Block Party.

“We’re kind of limited in the kind of fireworks we can shoot off,” said Julia Diamond, Grand Park’s programming director. “We have a beautiful park and architecture, so we want to be extra careful.”

For the past three months, Diamond and her staff have been meeting regularly with Los Angeles Fire Department officials to come up with a way to have a fireworks show that will still bring plenty of oohs and aahs. Traditional rockets that explode hundreds of feet in the air were ruled out; they leave behind burning shells that require a fallout zone to prevent fires and keep people safe.

Luckily, this is Tinseltown, where special effects and pyrotechnics are serious business. A local company, J.E.M. FX, was tapped to design a display suitable for the venue’s first-ever Independence Day celebration. They plan to use “proximate pyro” effects, designed to dazzle crowds at close range. Ron Smith, vice president of theatrical operations for the company, said the show will be similar to those you’d see at the Super Bowl or a music festival. The lack of big rockets won’t make it any less impressive, he said.

“It’s more up-close and personal,” Smith said. “You can design effects close to the music beats—because it’s close to the ground you can choreograph better.”

The fiery display will take place on the park’s middle block by the Court of Flags. Guests can spread blankets on both sides of the show, either on the grassy block in front of City Hall or the block in front of The Music Center, where the restored Arthur J. Will Memorial Fountain is located and where most of the night’s other entertainment will take place. The fireworks display will last about 10 minutes and use about a thousand different effects.

The brand of pyrotechnics won’t be the only non-traditional entertainment. As part of its continuing celebration of L.A.’s diversity, “the park for everyone,” as Grand Park bills itself, will avoid things like the 1812 Overture or the pomp of John Philip Sousa. KCRW DJ Anthony Valadez will spin globally-influenced dance music and L.A.-based artists Ethio Cali and Jungle Fire will perform live world music. Young slam poetry stars from Get Lit will perform at the event, too, as they brush up for national competition.

Of course, no outdoor event in L.A. is complete without gourmet food trucks. Game On Gourmet and the Rollin’ Rib BBQ Joint will be among the culinary fleet stationed at both ends of the park.

The music starts around 4 p.m. and the pyrotechnics will begin around 9 p.m. Parking is available at the Music Center and other lots, but the best bet may be to take Metro’s Red Line to the Civic Center/Grand Park station. Visitors who bring their TAP transit pass can pick up a free pair of Grand Park sunglasses at the information booth.

For organizers like Diamond, major holiday events like this are an opportunity to realize the park’s mission.

“The 4th of July is a chance for Grand Park to fulfill the role it was designed to play in this city,” said Diamond. “Grand Park is meant to be the civic heart of L.A.”

Posted 6/27/13

Taking a bite out of animal cruelty

April 11, 2013

Abusers beware: Eva Montes and her crack team in the county animal control department are on the case.

What began 15 years ago simply as a promising job for a struggling single mom of three youngsters, has become a calling. “I am a voice for the animals,” says Eva Montes.

Those animals have come in all sizes and shapes, from furry to feathered, but they’ve suffered a common fate: they’ve been treated badly by people—sometimes through ignorance, sometimes with malice. And it’s not just about the animals.

“Most serial killers started with abusing animals,” Montes says, “and we have to put a stop to that early.”

Montes belongs to a select squad inside Los Angeles County’s Department of Animal Care & Control that investigates the agency’s most complex cases of animal neglect and cruelty. Called the Major Case Unit, its seven members tackle everything from highly organized pit bull and cockfighting rings to cat hoarders to single cases of heartbreaking—and criminal—abuse.

On Tuesday, she was among more than a dozen uniformed colleagues picked to represent the department before the Board of Supervisors as part of “Animal Control Officers Appreciation Week in Los Angeles County.” While the agency is best known for its shelter system and efforts to find adoptive homes for animals, the largely unsung detective work of its Major Case Unit, or MCU, is central to the agency’s mandate.

“By our very mission, we’re charged with protecting the public and protecting animals,” says Deputy Director Aaron Reyes, who oversees the unit. “One of the best ways we can do that is to investigate crimes of cruelty, abuse, neglect and illegal animal fighting.”

Reyes says the MCU was created more than a decade ago when it became clear that the massive volume of calls handled by animal control officers was preventing them from undertaking sustained and difficult investigations. Until last year, the MCU had been based in the original “pound master’s house” at the department’s first-ever facility, which opened in Downey in 1946. But Reyes says he thought it was crucial to get the team’s members “onto the front lines” and base them in various shelters, where they could initiate investigations more quickly and share their expertise and insights with other officers.

The idea to scatter the team was not met with enthusiasm.

“We were against it,” recalls Montes, who’s been in the unit for nearly three years. “We hung out together. We were family. But it’s worked out better.” Since being assigned to the Carson Animal Care Center, Montes says, she’s found potential abuse cases “that were slipping through the cracks” because some officers were not creative enough in their investigations or sufficiently trained to spot signs of less obvious abuse or neglect when people were bringing dogs to the shelter.

Since last July, Montes says she has, for the first time, initiated a number of investigations of people who’ve brought dogs to the facility, including a woman who recently turned in a pit bull that looked like it had been used for fighting. A warrant for her arrest was recently issued. Last November, Montes was instrumental in a joint investigation with the SPCA Los Angeles that led to a long list of cruelty charges filed by the district attorney’s office against the owner of a Gardena guard dog business.

Being assigned fulltime to the Carson shelter, which serves some of southern Los Angeles County’s most impoverished neighborhoods, has been a culture shock for Montes. Before her promotion to the MCU, she spent nine years in the county’s Agoura Animal Care Center, high in the mountains above Malibu. She calls it “the Club Med of shelters.” The dogs, she says, are mostly of the “frou-frou” variety, and volunteerism is robust, something for which she’ll always be grateful on a very personal level. During Montes’ tenure there, her 14-year-old daughter died from a form of bone cancer. Volunteers built a misting system to keep the animals cooler during the summer months and dedicated it with a plaque in honor of Montes’ daughter, Jessica.

“She really respected my job,” Montes says of her girl. “If she could only see me now.”

In contrast to the Agoura shelter, Montes’ current assignment has exposed her to some of the meanest dogs and toughest owners in the department’s jurisdiction, a swath of southern Los Angeles County where “gang members represent themselves with their dogs.” Sometimes, she says, packs of “dominant breed” dogs such as Rottweilers and pit bulls roam the streets. “It’s scary,” she says. “I worry about getting bit and never being able to work again.”

Montes says she’s received cooperation during her neighborhood investigations but has been told by some male officers that they’ve encountered resistance when responding to complaints, being warned: “Get off my property or I’ll shoot you.”

One of Montes’ colleagues in the Major Case Unit is Armando Ferrufino, who, like her, also works in the southern part of the county. An expert on cockfighting, he’s assigned to the Downey Animal Care Center. And like Montes, he also feels as though he’s a voice for the animals.

He tells the story of a man who, for months, allowed his Rottweiler, Duke, to deteriorate into a mass of tumors and sores, refusing to seek medical help despite the animal’s obvious suffering. Acting on a tip, animal control officers rescued Duke, but he was too far gone to save.

“I felt like the spirit of the animal was telling me to do the right thing, to investigate and get the whole truth,” Ferrufino says. “And I did.” The owner was charged with a felony and sentenced to three months in county jail.

Ferrufino, who joined the MCU in 2009, says one of the most sensitive assignments involves animal hoarders, mostly lonely elderly people whose homes are filled with scores of cats, a good number of them ailing. “In their mind,” Ferrufino says, “they believe they are doing the right thing—showing them love—but it gets to the point where they can’t take care of them.”

If the neglect is severe, he says, then charges are pursued. Authorities also provide referrals for counseling. What’s more, the county has a program to help clean homes after animals have been removed during often tearful negotiations with owners. “It’s an illness,” Ferrufino says. “They’re not aware they’re doing something wrong.”

As difficult and wrenching as the work can be, Ferrufino says, he’s found his calling, too.

“Every day I come to work, I’m happy,” he says. “You don’t know what’s going to happen next, from hoarders to horses to cockfights.”

Montes agrees. “Some people like to stay in the shelter environment. But I saw other officers out there getting justice and I said: ‘That’s what I want to do.’ “

Posted 4/12/13

Vote and help spread a cool $1 million

April 11, 2013

The candidates are out there, stumping for votes, inundating inboxes, taking to Twitter and Facebook to spread their messages.

No, we’re not talking about a certain upcoming mayoral election—although, like that contest, the outcome of this one could have ramifications for the future of Los Angeles.

This hotly-contested race is called MyLA2050, and the candidates, all 279 of them, are vying for a piece of a $1 million pot that aims to underwrite 10 of the best ideas for changing life here for the better.

It’s crowdsourcing with a conscience. And to scroll through the entries is to peer into the idealistic, entrepreneurial, only-in-L.A. psyche of a metropolis in transition.

Want to support a door-to-door urban composting program?

Underwrite a rolling neighborly Potluck Truck?

Jumpstart an off-the-grid, self-sustainable artists’ habitat called ValhalLA?

Here’s your chance to cast a vote—and just one, according to the rules—for the project that captures your imagination, or your heart. While public voting won’t directly award any money, it will determine the top 10 vote-getters in the eight categories from which winners will be chosen by the Goldhirsh Foundation, which is sponsoring the initiative. (The categories are education, environmental quality, health, social connectedness, art and cultural vitality, income and employment, housing and public safety.) Two other “wild card” projects will be selected as well—regardless of whether they receive popular acclaim. Each of the 10 winners will receive $100,000 to implement their idea.

On social media, the politicking is getting fast and furious as the voting deadline—high noon on April 17—approaches.

“HoneyLovers! Can you spare 30 seconds to help us out? We are in the running for a $100,000 GRANT to help make Los Angeles PESTICIDE FREE! We would LOVELOVELOVE your support! PS—You do not need to live in Los Angeles to vote for us so spread the buzzzzz!!!” read one appeal on Facebook from the beekeeping-promoting HoneyLove (aiming for a “Pesticide-Free Los Angeles 2050.”)

And that’s far from the only get-out-the-vote effort going. “We are gaining momentum in the voting. We are not there yet,” said a recent post on behalf of the Potluck Truck candidate from Project Food Los Angeles. “One of our members is counting on this grant to tell her father to back off the consistent pressure to get a real job! A victory here would be a strong validation of the power of ideas…we think it’s a good one! Please VOTE!”

Some, like the Eagle Rock Yacht club, which promotes dodgeball as a gateway to youth education programs, are offering incentives: folks who vote for the project get $10 off the $45 fee for the organization’s spring leagues.

Fallen Fruit's "Endless Orchard" envisions fruit trees and mirrors combining to make an art project full of contrasts.

In the midst of the all the competing appeals, however, some would-be voters seem stymied by the contest rules, like one who recently asked on Facebook: “Am I the only one who finds this confusing? Can we vote for one each in multiple categories? Or just for one? I have so many friends who are competing for this!”

Others have run into frustration because the voting website won’t open on older versions of Internet Explorer. (Contest organizers suggest using Firefox or Chrome browsers.)

“At first it was kind of nail-biting because I’m very passionate about the idea and I wanted everybody to hear about it. I was blasting it out there,” said Courtney Carter, who’s promoting the ValhalLA artists’ habitat. She said she’s been checking the contest leader board “like every second” to see how her entry is faring with the voting public.

Vivian Liao of City Earthworm, who’s behind “You Can Compost That!” has also been an energetic stumper.

“I do a lot of Facebook and Twitter campaigning. Obviously, there’s a lot of friends-and-family bugging,” she said. “I’m blogging about this also.”

It’s understandable that some people are having a hard time choosing which program to back. There are entries from famous institutions like the county Natural History Museum (proposing an Urban Safari program to “discover and document” the biodiversity of the L.A. Basin) and candidates from tiny outfits like HoneyLove. Naomi Ackerman’s Advot Project seeks to change the lives and relationships of teenagers through theater and dramatic exercises. Community Builders Resource Network wants to bring charitable organizations together for greater impact.

Some contenders grew out of established success stories, like the heartwarming international video sensation Caine’s Arcade, or L.A.’s favorite car-free rolling block party, CicLAvia. Others are more niche (“Beautiful Rain Barrels in Public Places.”) Some are big (“The Million Reusable Bag Giveaway”), some are small (“Park-in-a-box”), some sound like poems (“Endless Orchard”) and some sound like they’re on a mission (“Empowering Teens with the Knowledge and Skills to Make Healthy Decisions.”)

There are concepts for apps and maps and pop-ups. Garden-related ideas are huge, and there are a number of proposals advancing new, socially-conscious purposes for food trucks. The Los Angeles River figures in at least two: A temporary summer riverfront park and an Elysian Park “swimming pool/industrial cistern” to be used as a public plunge.

And like any campaign, there are the catchy slogans and exhortations: “Kids who sling kale eat kale,” ”Dodgeball, prosperity and the Common Good,” “State of the art lighting for city parks!”

The contest is part of a broader initiative, sponsored by philanthropist and GOOD magazine founder Ben Goldhirsh, to rethink the future of L.A. A report—“Los Angeles 2050: Who we are. How we live. Where we’re going.”—was released in February, with the aim of stimulating “an outbreak of idealism that strengthens civic engagement, challenges the status quo, and demands more for the future of Los Angeles.”

Shauna Nep, a social innovation manager on the project, said the contest is a way to bring more attention to the findings in the report and to “create a more participatory and transparent process” for tackling some of the challenges it explored.

The $1 million derby brought out a wide range of entrants, she said—“a lot we were familiar with, and some we’d never heard of before.”

And, while it has not received much attention in the mainstream media, she noted that it has been a lively topic on blogs and social media networks.

“We’re overwhelmed,” she said.

Meanwhile, don’t worry that you’ll have to wait around till 2050 to see your favorite innovations take shape. The rules call for all the winning projects to be implemented this year.

Posted 4/11/13

Dry time for county’s new storm boss

March 27, 2013

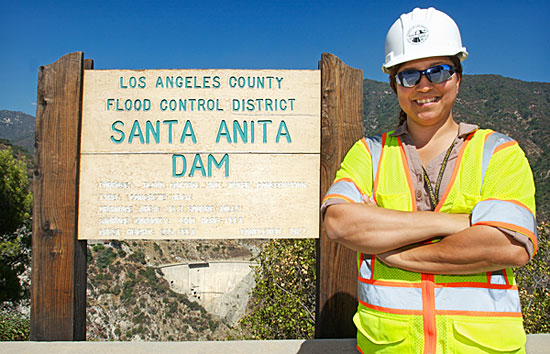

Meet L.A. County's storm boss, Michele Chimienti. Rainfall's been light during her first winter on the job. Photo/Public Works

If this was a normal year, water would soon be gushing from the Los Angeles County dam system’s reservoirs. It would be surging down rivers and channels, rushing into spreading grounds to be filtered and recycled, and flowing through wildlife habitats where it would sustain plants and animals through the long, hot summer.

But this is not a normal year.

For the second season in a row, winter storms have largely bypassed Los Angeles County and much of California. Local rainfall levels so far have reached only 37% of normal levels, and prospects for the kind of sustained, heavy rain required to make up the difference seem increasingly unlikely. (The storm that’s been forecast for this weekend isn’t expected to do much to bring county reservoirs—now holding just 5.5% of what they’d stockpile in a normal year—back up to where they should be.)

What’s more, a “new normal” seems to be emerging. Just ask Michele Chimienti, the county’s new “storm boss.”

“We’re seeing more of the high-highs and the low-lows. Nothing’s really normal. There’s no average,” said Chimienti, a county Public Works engineer who, since October, has been in charge of operations for the department’s water resources section. “You have one extreme or the other. Like in 2005, we had our historic wet year. That’s obviously an extreme. Then we had a dry year last year.”

For consumers, such extremes can be a pocketbook issue, with water rates going up and conservation programs aimed at lowering outdoor water use being heavily promoted—from “Cash for Grass” to “ocean-friendly” gardening.

For the water pros, the seasonal extremes are a challenge to business as usual. As hanging onto every possible drop of rainwater becomes increasingly crucial in Southern California, Public Works is accelerating its efforts to modernize and expand water retention capabilities throughout the region. (A list of completed and upcoming projects is here. Such efforts also are a central element in the proposed Clean Water, Clean Beaches parcel tax; the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors has asked for more details on the measure before deciding whether to place it before voters next year.)

And for those like Chimienti on the frontlines of storm water management, the dry spell has posed its own kinds of challenges—of the lonely Maytag repairman variety.

“I actually would have loved it if we’d had a wet season. That’s what we thrive on,” Chimienti said. “It does get a little frustrating when we have dry year upon dry year.”

Still, she and her team are using the time in which they’d ordinarily be controlling and diverting fast-moving stormwater to make needed repairs and upgrades to the system.

“This is our downtime right now because it has been such a slow storm season,” she said, “so we’re looking toward the future: what can we do to improve our water conservation in all of our facilities?”

Even though she hit a dry patch in her first winter on the job, the 40-year-old Chimienti has seen plenty of storm activity in years gone by.

“You can volunteer for storm duty, and I did that for the past six, seven years,” she said. “It’s a good way to learn the facilities. You see the river. You see how it reacts. You get a good idea of the amounts of water, the quantity of flow that’s coming down. You get to learn the names of all the flood maintenance guys who actually do this day in and day out, run up and down the rivers, making sure people are out of the flow when water’s coming down, making sure it’s safe.”

Chimienti, the first woman to serve as the county’s “storm boss,” was named a Top Young Leader last year by the American Public Works Association, testament to her work in her previous assignment: project engineer on the $100 million Big Tujunga Dam retrofit.

The work on “Big T,” as the dam is affectionately dubbed within Public Works, focused primarily on bringing the facility up to modern seismic safety standards. But an added benefit was that a reinforced reservoir could hold—and hang onto—much more water in the wet years.

“We’re able to conserve an additional 4,500 acre feet a year,” Chimienti said. (An acre foot is approximately 326,000 gallons.)

That kind of capacity is crucial when the amounts of rainfall vary so widely from year to year. As for what’s behind the variations, Adam Walden, senior civil engineer in Public Work’s water resources division, said they might be attributable to climate change but “we don’t know for sure.”

“What is known is that, in recent years, we are seeing extremes in L.A. County’s rainfall,” according to Walden. “We have had both the wettest year on record (40.5 inches in 2004-2005 season) and the driest year on record (3.6 inches in 2006-2007 season.)”

And that, Chimienti said, means it always makes sense to conserve.

“Don’t waste it,” she said. “It is a vital natural resource, and it’s not limitless.”

Effects of dry winter are visible at county's Cogswell Dam in the San Gabriel Mountains. Photo/Public Works

Posted 3/27/13

Check for the latest closure information

Check for the latest closure information