Top Story: Environment

The (new) end of the trail

May 30, 2014

For years, hikers have been banned from Malibu’s Puerco Canyon Trail and the rest of a stunningly scenic 703-acre property in the Santa Monica Mountains, mostly owned by film director James Cameron.

According to Paul Edelman, chief of natural resources and planning for the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy, visitors were met with barbed wire and security teams until a few years ago, when they were finally allowed to walk through the oak-studded property, home to a variety of wildlife.

Still, access has stopped short of the end of the trail. At one point along the way, hikers are met with a chain link fence that keeps them from connecting to the adjacent Corral Canyon Trail. And hikers on that popular 2.5-mile loop have been stymied by that same fence, which prevents them from heading into Puerco Canyon.

But that final barrier is about to fall: On Tuesday, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors approved a $6 million allocation to help purchase Cameron’s acreage. Also contributing to the purchase: $4.5 million from the Wildlife Conservation Board and $1.5 million from the California State Coastal Conservancy.

The new owner, the Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority, will oversee the property with the goal of preserving open space, habitat and resources. Once escrow closes, a date for public access will be set.

The collective 24 parcels of land known as the Puerco Canyon Properties, formerly slated for housing development, represents a major piece of the geographic puzzle in Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s longstanding effort to foster preservation and public access in the Santa Monica Mountains.

The property will dramatically increase access between 1000-acre Corral Canyon Park and the 7,000-plus-acre Malibu Creek State Park, Edelman said.

“It’s the last big piece in the Malibu State Park core habitat areas,” Edelman continued. “There aren’t too many big ownerships left in the Santa Monica Mountains. This is the last big sucker in L.A. County.” (The remaining large private properties in Ventura County are the 1000-acre Deer Creek Canyon property owned by the Mansdorf Family Trust and the even larger Broome Ranch).

The “last big sucker” is significant for more than its size. Contained within its borders are major sections of the new Coastal Slope Trail. This project-in-development includes a small portion of the existing Puerco Canyon Trail and will eventually run about 65 miles from Point Mugu State Park on the coast to Topanga State Park in Topanga Canyon.

Not only does the parcel facilitate new trails—its acquisition serves to preserve a delicate ecosystem. According to the coastal conservancy’s project summary for the purchase, the Santa Monica Mountains “encompass a rare biome that can be found in only four other locations on the planet.”

Vegetation and wildlife include native grassland, chaparral, coastal sage scrub, sycamore-willow woodland, oak trees and a wealth of animals, including mountain lions, bobcats, and gray foxes.

Said Edelman: “You could say that it probably has one of everything, animal-wise, with the exception of maybe salamanders. My guess would be 15 of the 19 snakes in the Santa Monica Mountains are down there, just because it’s so big.” The acquisition will also protect drainage areas that play an important role in the movement of wildlife in the area.

Not bad for a former pig farm. Along with its small enclave of luxury houses, Puerco Canyon was once home to a sprawling pig farm that existed into the 1980s.

That’s good for hikers too, Edelman said. “There’s a portion that has not been accessible to the public that has a whole system of neat little trails that were carved for the pig farm,” he said. While the trails were created for farm vehicles, they’re trail-ready for hikers and their dogs — or any pet pig that might choose to tag along.

Posted 5/30/14

A high note for mountain protections

April 17, 2014

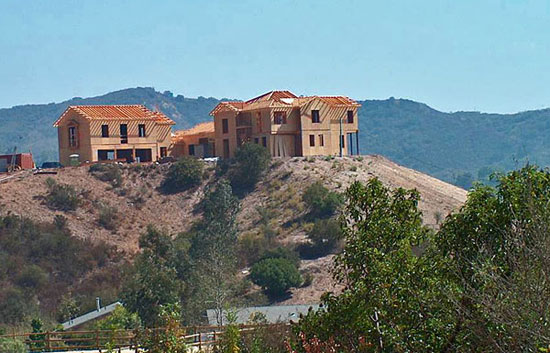

Ridgeline developments like this will be banned in the Santa Monica Mountains by the county's new rules.

In a vote that will resonate for generations, the California Coastal Commission this week cleared the way for the enactment of a wide-ranging plan to protect the Santa Monica Mountains from development that already has scarred portions of one of the region’s most important environmental and recreational resources.

The 12-member commission voted unanimously in favor of a land use plan adopted last month by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, despite strong opposition from real estate development interests. The Coastal Commission vote was mandated by state law and represents a milestone in the years-long effort to preserve the mountains along the coast as a rural escape for tens of thousands of visitors each year.

The plan will, among many other things, ban ridgeline development, save oaks and other native woodlands, outlaw poisons that can harm wildlife, protect water sources, restrict lighting to preserve the night sky and prevent the opening of new vineyards, which take a toll on the land and water.

“This is a stunning achievement, to get a unanimous vote on a plan that has been on-again, off-again for three decades,” said one of its strongest advocates, Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, whose district includes the Santa Monica Mountains. “It’s a tribute to all the stakeholders—environmentalists, equestrians, homeowners, agricultural interests, among others—who came together to find common ground.”

During testimony before the Coastal Commission on Thursday, Yaroslavsky said he had spent two decades on the Board of Supervisors “fighting against ill-conceived developments that have desecrated” the mountains. He told the commission that it now had a “historic opportunity” to stem the damage, an opportunity the commissioners seized.

They left virtually untouched the county’s proposed plan, which was crafted by Yaroslavsky’s office and the Department of Regional Planning. The only substantive addition was a clause that expressly affirmed the right of residents to grow organic gardens through ecologically sound farming methods—a move considered necessary because of misinformation that had been spread about the plan in the days leading up to the commission’s vote.

Much of Thursday’s day-long hearing in Santa Barbara was consumed with people testifying in support of the county’s plan. But one woman used her time to blast the 11th-hour falsehoods aimed at derailing the plan by claiming, among other things, that food gardens would be banned.

“It’s just not fair to those of us who aren’t experts to be given emails that say you’re not going to be able to grow your own food,” said Janet Friesen of the Natural Resources Defense Council. “I’m here to say that I don’t think it’s right when there are paid lobbyists who are misleading people.”

Leading the campaign against the county’s plan, called a Local Coastal Program, was Don Schmitz, a consultant and lobbyist who also owns a vineyard in the Santa Monica Mountains. Under the plan, existing vineyards can remain in business, although no new ones would be allowed to open—a restriction that Schmitz criticized during his testimony on Thursday.

He disputed the negative environmental impacts of vineyards, calling the businesses a “significant draw to the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area.”

“Not everybody is able or even wants to throw on a backpack and do 10 miles on the Backbone Trail,” Schmitz said of one of area’s tougher hikes.

Now that the Coastal Commission has endorsed the plan’s policy direction, it will take another vote in the months ahead on the details of its implementation. The matter will then move back to the Board of Supervisors for a final vote.

Posted 4/11/14

Charting a sea change

March 20, 2014

Hotter heat waves in the Valley. Smaller snowcaps in the mountains. Worse flooding during storms on Pacific Coast Highway. Study by study, local scientists are gradually pinpointing the ways in which climate change could impact Southern California. The news has been sobering.

Now, the county is preparing to zoom in on another piece of the picture, with a look at rising sea levels at the 21 beaches it operates and maintains. Approved this week by the Board of Supervisors and funded in large part by a grant from the California Coastal Conservancy to the county Department of Beaches and Harbors, the $86,815 study will run from April to October, and add to a growing body of work on the local impact of climate change.

“There have been broad projections about what sea level rise might look like, but that picture isn’t specific enough for what planners and policy makers need,” says Megan Herzog, a fellow at the UCLA law school’s Emmett Center on Climate Change and the Environment.

Although the City of Los Angeles has made some headway, most notably with a recent study on the potential impact of sea-level changes along the city’s coastline, “most local governments are just at the data gathering stages,” says Herzog. “So we’re really just at the beginning of thinking about impacts and making plans.”

With more than 52 million visitors a year just at the beaches that are county-owned or -managed, a full assessment of the coastline’s vulnerability is critical both to the environment and to the economy, says Kerry Silverstrom, chief deputy director at Beaches and Harbors.

“One study found that sea levels on the West Coast have risen twice as fast over the last five years as they did over the last twenty,” says Silverstrom, noting that the sea level is projected to rise by up to two feet by 2050. “So we need to look at what are we going to do as operators of the beaches to protect them?” she says.

Higher tides not only can flood low-lying buildings and roads, but can also exacerbate storm damage by undermining parking lots and damaging coastal sewer lines. These issues are of particular importance on the county-maintained and operated beaches, which range from Royal Palms in the South Bay to Malibu’s Nicholas Canyon, and include such landmarks as Marina Del Rey, Point Dume and Venice Beach.

The city’s January sea level study, done in cooperation with USC, found that the Port of L.A. and energy facilities along the coast were in good shape to withstand the impact of rising sea levels. However, low-lying communities such as Wilmington, San Pedro and Venice are especially vulnerable, as is Pacific Coast Highway, which already floods regularly in some places when winter storms hit.

The study found that even a moderate storm could do more than $400 million in damage on the city’s share of the beaches if the sea level were to rise here by just 18 inches or so, a mark that easily could be reached by 2050. Also at risk are wastewater and drinking water systems near the high tide line.

Charlotte Miyamoto, head of the planning division at Beaches and Harbors, says the county’s research will have big implications for county public works projects such as sea walls and sand berms—protective structures that the county uses to prevent crashing waves from scouring beaches, undermining parking lots and flooding Pacific Coast Highway.

Although critical in mitigating the ocean’s impact on infrastructure on which the public relies, residents in Venice and Marina Del Rey have complained that the temporary berms, in particular, block their view of the ocean—a complaint that seems likely to be amplified as rising sea levels raise the risk of damage from storm surges.

“How big and wide will we need to make those berms?” says Miyamoto. “Will we want to build structures in the water to deal with erosion? The beaches are our first line of defense as the sea level rises,” says Miyamoto, “and so we want to make sure they’re preserved.”

More broadly, the county study also will help focus policy choices, says Herzog. Already, she noted, coastal cities elsewhere in California are moving bike paths and other amenities away from narrowing beaches and rising tides.

“This region is really densely developed along the coast,” she says. “In some cases, we have development right up along the backs of beaches, and that’s going to mean we have to think about priorities. We have to decide if it’s important to preserve beaches and wetlands and ecosystems, for instance. And if it is, then it’s going to mean tough decisions about development up and down the coast, and it could mean major changes in land policy over the long term. Because something has to move.”

Silverstrom noted that the Beaches and Harbors study, while narrow, is just one part of a broad effort the county has been undertaking for the past two years to prepare for climate change. A series of climate change studies led by the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability has projected, among other things, that average annual temperatures in Greater L.A. will rise by an average of 4 or 5 degrees by 2050, that days of extreme heat will quintuple in inland areas and the valley and that the area’s mountains will get about a third less snowfall.

So, acting on a 2012 motion by Supervisors Zev Yaroslavsky and Michael Antonovich, county departments across the board have been assessing the potential impact of climate change and trying to mitigate its potential costs.

The county Fire Department, for instance, has revised training protocols to account for the warming climate. The Internal Services Department has been working to reduce the carbon footprint at county buildings and to improve energy efficiency. The Department of Public Works, meanwhile, has been trying to capture more storm water, and to replace gas-fueled trucks with more eco-friendly vehicles.

Silverstrom of Beaches and Harbors says the latest study will help pave the way for short, medium, and long-term solutions to rising sea levels, coastal erosion and more powerful storms in the future.

“This is about resilience,” she says, “about how we can sustain our beaches for the public while recognizing what’s happening in the environment.”

Drought reigns in plant kingdom

February 6, 2014

A volunteer helps plant one of 24,000 seedlings that have languished in a nursery because of drought conditions on hillsides charred by last year's massive Springs Fire. Photo/Steve Friedman

Last spring, after Sycamore Canyon was devastated by the earliest fire season in memory, Irina Irvine raced to protect the scenic landmark from an ancillary threat.

A restoration ecologist with the National Park Service, Irvine had been working to rid the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area of destructive non-native grasses. Some of her most successful work had been in the hills around Newbury Park, where, in May, the fire had started.

Knowing that opportunistic plants could retake and wreck the natural ecosystem if she didn’t act quickly, Irvine prepared 24,000 native seedlings—elderberry and oak, coastal sage and purple needle grasses. Then she waited for the winter rains, when the sprouts could be planted.

And waited. And waited.

“Twenty-four thousand plants at $3 a plant, and several interns hired especially for this,” says Irvine. “And it hasn’t rained yet.”

Lawns aren’t the only landscapes that are starting to feel the effects of this year’s extreme drought. From street medians to coastal canyons, local naturalists say the shortage of water is having all sorts of unprecedented impacts.

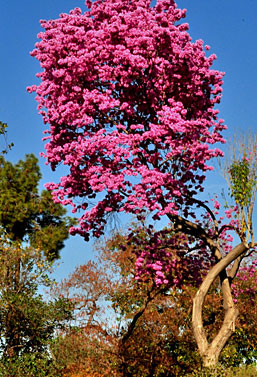

At the Los Angeles County Arboretum and Botanic Garden, the absence of soil-cooling rain has tricked spring-blooming trees into blossoming as if it were April. In the San Fernando Valley, meanwhile, wildflowers are failing to germinate for lack of water.

In the Angeles National Forest, the drought has not only dried up natural springs but also emptied rain-catching “guzzlers”, small man-made reservoirs that provided a reliable fallback in past years for thirsty birds and wildlife. In the Santa Monica Mountains, the extreme water shortage has made historic oaks vulnerable to bark beetles and weakened even resilient trees such as eucalyptus.

“There’s been a lot of die-off in the native vegetation,” says Florence Nishida, a resident of Topanga Canyon and master gardener at the Museum of Natural History. “Landscaping at least has some source of water. But in the natural areas, the plants have gone since last March or April until now with hardly a drop of rain.”

Frank McDonough, botanical information consultant at the Arboretum, says the region is feeling a triple whammy—a years-long drought combined with a warmer-than-usual fall and winter and a high-pressure ridge that has cut off California’s usual dose of rain. Without a series of good, soaking downpours to cool down the soil, he says, the tree roots don’t realize it’s winter, and that, plus last month’s record heat, has left plants confused.

“Now our pink trumpet trees, which usually don’t bloom until March, are covered in blossoms, and the flowering apricots and nectarines are starting to bloom,” says McDonough, adding that more than a year or two of such unusual conditions can weaken trees and leave them vulnerable to disease and insects. Although it’s not necessarily good news, he says, “I expect the cherries will bloom earlier than normal, too.”

In wildflower country, on the other hand, the lack of rain is just depressing.

“It’s been pretty pitiful for the past two years, and it will probably be the same or worse this year,” says Lili Singer, director of special projects and adult education at the Theodore Payne Foundation, a Sun Valley nonprofit that operates an annual wildflower hotline.

For a good show, she says, wildflowers need at least one serious rain per month, starting in the autumn, so that they can establish themselves and produce plenty of buds before they start flowering. But with the exception of man-made seed-sowing initiatives such as Wildflowering L.A.—whose gardeners have been forced to water their supposedly drought-tolerant seedlings far more than expected—and the possibility that a few rare species will sprout in the wake of recent brush fires, Singer and other naturalists say they don’t have high hopes for this season.

“There’ll always be something for people to see,” says Singer, “but it will be a lot lower in the number of plants and the diversity.”

Nor are the wildflowers the only living things that are thirsty. In the Angeles National Forest, for instance, the county this week approved a grant to repair watering stations for wildlife and birds.

“This drought has just been real tough,” says John Forgy of the San Gabriel Valley chapter of Quail Forever, an organization that has offered to make the repairs as part of its work supporting wildlife. “And some of the young birds only eat insects, and there are no insects if there’s no rain.”

Irvine of the National Park Service says she has seen all these drought symptoms and more in the Santa Monica Mountains, where, in the plant world at least, “everything’s a little wacky right now.”

Vegetation, she notes, is vital in wildlands, not only because it’s habitat for wildlife, but also because it prevents erosion and counteracts global warming by sequestering carbon dioxide.

In areas like the mountains, where many species have evolved around drought, a dry year or two isn’t necessarily alarming.

“But you can only push so far before you reach a tipping point,” says Irvine. “When I see a big eucalyptus that’s been here for 50 years dying because there’s no water, that catches my attention. Pine trees are being hammered. And we are already seeing significant die-back in chaparral communities, and we don’t know if they’ll pop back up again if it rains, or if, when it’s gone, it’s gone.”

Particularly unnerving has been the effort to restore those 10 acres near the Wendy Trail head near Newbury Park at Rancho Sierra Vista in an area that was consumed last May during the freakishly early Springs Fire. Fueled by Santa Ana winds that had sucked the humidity in the air down to the single digits, the blaze swept from the canyons to the surf, consuming some 24,000 acres of drought-dried Los Angeles and Ventura Counties.

Among the casualties were some of the most scenic spots in the Santa Monica Mountains, including acreage on which Irvine had spent months trying to eradicate a particularly toxic and invasive strain of Australian bunch grass. The plan was to replant the area as quickly as possible with native seedlings that Irvine had carefully sprouted and set aside in a nursery.

“Normally what one does is wait for the first soaking rain of the year and then run, quick like a bunny, to get the plants in the ground as soon as the soil softens,” says Irvine. She had banked on an autumn planting. “But then when it didn’t rain in October, we were, like, ‘Darn it’,” she says. “And then no rain again in November. Darn it. And then December. And it was, ‘Are you kidding me?’”

The longer they waited, she says, the harder the earth got, making it even more difficult to transplant the seedlings that were in the nursery. And letting 24,000 seedlings die at $3 per seedling was not in the plan.

So when January came with no rain, she says, “We just said, ‘That’s it—we’re planting.’” Since January 17, Irvine says, she and a crew of interns and volunteers have been struggling to get the groundcover into the earth, which is so hard and dry that they’ve had to drill holes for the plants with a motorized augur.

“That’s 24,000 holes,” she says. “It’s been very slow going. We’ve only gotten about 9,500 plants into the ground, and we’ve been out there every day but Sunday and Martin Luther King Day.” Most recently, she says, she set aside $10,000 so she could water the plantings if necessary with a fire hose and a water tanker.

“If it rains substantially, of course, all bets are off,” Irvine says. “But from what I understand, just to get back to normal we’d have to have a couple of inches a day from now until about May.”

"You can only push so far before you reach a tipping point,” Irina Irvine says of the drought. Seen here in green, she gets the troops ready for planting seedlngs in the hard dirt. Photo/Steve Friedman

Posted 2/6/14

The state of the shark

January 29, 2014

Last July at the end of a long beach day, a Los Angeles County Sheriff’s helicopter spotted a 6-foot-long great white shark off of El Porto Beach. The copter’s loudspeaker was so clear that some South Bay locals heard it at home in their kitchens: Exit the water immediately.

To authorities in the air, it made perfect sense to issue a warning. Down on the sand, however, the sighting was familiar to county lifeguards—a baby great white feeding on small fish and stingrays, off the coast of a county that hasn’t seen even a hint of shark trouble in 25 years.

More broadly, however, the incident underscored the recent rise in local shark encounters, and the lack of a clear, uniform local policy on how to handle them. That’s why the Los Angeles County Fire Department’s Lifeguard Division will be hosting a symposium at Dockweiler Beach on Friday for local public safety personnel, elected officials and researchers. Organizers say the event is intended partly to work toward a policy consensus and partly as an opportunity to examine the state of the great white shark on beaches here.

“To my knowledge, no one has ever been fatally bitten by a great white in Los Angeles County,” says Chris Lowe, a marine biologist who leads the Shark Lab research center at Cal State Long Beach. (A suspected 1989 attack off the coast of Malibu was handled by Ventura County and never confirmed.)

“But the sightings have gone up, and the numbers seem to be going up, too,” Lowe says. “So this is partly to bring water safety people up to speed.”

Great whites are the best known of about ten shark species that can be found off the Southern California coastline, Lowe says, but they generally prefer habitats that are rockier and colder. Female sharks are believed to migrate to this area to give birth to their offspring, which may be why the sharks that seasonally show up in our waters tend to be juveniles under 12 feet, Lowe says.

Because great whites are hard to tag, he says, their numbers are hard to pin down.

“But their populations do seem to be increasing,” he says. Theories range from cleaner water and recovering fisheries to the fact that, as a candidate species under the state Endangered Species Act, great whites are protected in California, so it is illegal to catch and kill them.

That, however, hasn’t kept thrill-seekers and shutterbugs from seeking them out in numbers sufficient to prompt another theory—that there aren’t necessarily more great whites in the water, just more cameras.

Last year, a bumper crop of SoCal shark encounters showed up on YouTube, from a viral helmet-cam clip of a young great white swimming under an audibly nervous paddleboarder to footage of a surf fisherman reeling in a 3-year-old great white near San Onofre.

“You have to be prudent,” Lowe says. “Even though most of those sharks off Manhattan Beach were babies, if someone chases and corners them, they’ll do what any animal would if it feels threatened—it will attack you. It’s generally not a good idea to chase a shark around.”

Though the few shark attacks that have occurred south of Point Conception have been in other counties, Lowe says that he can understand the desire for local consensus on policy.

“In Hawaii, for instance, we trained lifeguards and helped them develop procedures based on things like the size of the shark, whether it appears to be aggressive and whether there have been indications that people or animals have actually been bitten,” he says.

“So at this symposium, we’ll be talking about what can be done, whether to close the beaches or post notices or just pass the word to other lifeguards. And some areas may already have some of those policies in place.”

Dan Murphy, ocean lifeguard specialist for the Los Angeles County Fire Department’s Lifeguard Division, notes that local beaches fall into a variety of jurisdictions. Most are guarded by the county, but some have state or local personnel guarding the waves.

In years past, lifeguards say, the lack of a single local policy on great whites hasn’t mattered much because so few attacks happened. Baby great whites, they say, have been known to cruise right under a surfer and pose no danger.

“But that’s not to say that one of those might not take a left turn one day and chomp a stand-up paddler,” says Lifeguard Capt. Kyle Daniels, who notes that San Diego has a well-developed response policy for shark sightings. “Outside Santa Monica Bay, I’ve seen sharks eating sea lions—not at highly populated beaches, but still.”

Tom Ford, director of marine programs at the Santa Monica Bay Restoration Commission, says it is important for coastal stakeholders to educate each other as they learn more about co-existing with an important predator.

“This isn’t some scene out of ‘Jaws,’ ” he said. “These animals are part of a healthy environment and we want them to go through the course of their day without any harm to their natural movement.”

Posted 1/15/14

A beach for one and all

November 7, 2013

When it comes to reinforcing stereotypes of the California dream, few towns can match Manhattan Beach. Its finely-groomed sands draw scores of barely-clad stars of beach volleyball, including Olympic champions. Its waves are crowded with high-flying surfers and its shoreline bikeway is among the region’s most scenic.

But now, thanks to the persistence of a 90-something activist, the South Bay community is clearing the way for a new group of beachgoers to hit the sand, a group that’s certain to grow as baby boomers advance well into their senior years.

On Tuesday, the Board of Supervisors approved the drafting of an agreement between the city of Manhattan Beach and the county’s Department of Beaches and Harbors for the construction of a “Path to the Sea” that will provide access on the sand for people with disabilities.

Already, Santa Monica has two access ramps across the sand near the pier that stop short of the water, one made of wooden planks, the other of recycled tires. There’s also one that travels alongside the north jetty and at “Mothers Beach” in Marina del Rey.

But the permanent concrete path proposed for Manhattan Beach, which juts directly onto the sand, is the first of its kind for southern Los Angeles County-operated beaches. It will be located at the city’s northern end near the popular El Porto parking lot, where wheelchair ramps currently exist. From there, the 10-foot-wide path will extend 70 feet onto the beach, with a broad turnaround at the end, about 150 feet from the water’s edge.

The project represents an “a very interesting experiment” that poses challenges unmatched by other kinds of access for disabled people, said Chief Deputy Director Kerry Silverstrom of the Department of Beaches and Harbors. Foremost among those, she said, was determining how to construct a permanent path that won’t be undermined by eroding sand or damaged by tractors that drag the beach for trash.

“The beach is a natural resource that should benefit everybody,” Silverstrom said. “But it’s particularly complicated with urban beaches where a lot of grooming occurs…It’s hard enough to keep a bike path maintained. How do you keep these kinds of walkways maintained and free of sand for people who need them?”

Logistical questions like these kept the project on the drawing board for years, to the frustration of neighborhood activist Evelyn Fry, 98, the driving force behind the walkway, which will be constructed by Manhattan Beach, at an estimated cost of between $33,000 and $38,000, but cleaned daily by the county.

Fry, who is not herself disabled, championed the path as part of her active participation for decades in the civic life of the community, to which she moved in 1938. She could not be reached to discuss her latest success.

According to Manhattan Beach engineering technician Ish Medrano, Fry wanted the concrete path to extend to the shore’s edge. But that wasn’t possible, he said, because of the possibility of it being washed away by the surging sea. “I think she’s going to be a little disappointed,” Medrano said of Fry, who became so well known at City Hall that when she walked through the door “it was like an alarm going off: ‘Evelyn’s here!’”

Medrano described Fry as “the nicest woman” but “relentless” in her six-year crusade. “I think she’d like to see it completed before she passes away,” Medrano said, quickly adding: “She’s joked about that herself.”

Posted 11/7/13

Support floods the L.A. River

October 31, 2013

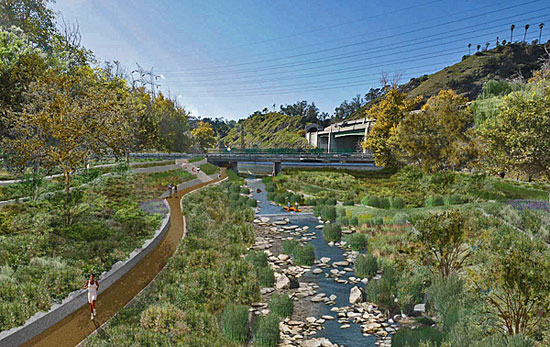

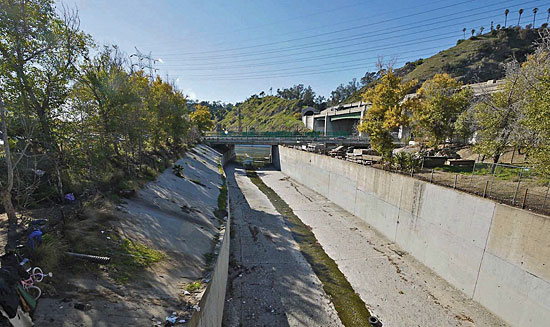

A greener Los Angeles River, as depicted in this rendering, is on the way under federal financing plans.

The Los Angeles River is getting a lot of love these days. The infamous concrete channel that’s been likened to a scar on Los Angeles’ civic psyche is now on the front burner to receive major improvements, and it’s got a lot of political muscle in its corner.

On Tuesday, as Mayor Eric Garcetti led a contingent of city officials and activists to rally support in Washington D.C. for a massive project to restore the river’s natural habitat and create more open space for the public, the L.A. County Board of Supervisors waded into the effort from a continent away.

Acting on a motion by Supervisor Gloria Molina, the Board voted 3-0 to back Alternative 20 of the Los Angeles River Ecosystem Restoration Feasibility Study, and to send a letter of support to federal agencies, President Barack Obama and the Los Angeles Congressional delegation. Supervisors Michael D. Antonovich and Don Knabe abstained from the vote. Alternative 20 is the most sweeping of four alternatives reviewed in the study—which was commissioned by the United States Army Corps of Engineers—and it comes with a $1 billion price tag that would be shared by the City of L.A. and the federal government.

Lewis MacAdams, president of Friends of the Los Angeles River, a non-profit group dedicated to restoring the waterway, said the Supervisors’ move adds much-needed momentum to the cause.

“It makes it clear on every level that the people of Los Angeles want to see the restoration of the river to the largest possible scale,” MacAdams said. “What you’re seeing from the Board of Supervisors is a commitment to the restoration of the river from the area’s most powerful political body.”

When the Corps released its study on plans to restore 11 miles of the river between Griffith Park and downtown L.A. last month, the long-awaited report met with a lukewarm reception. Of the four alternatives analyzed, the Corps tentatively recommended Alternative 13, the second-least-extensive option. It would restore 588 acres of habitat and create four miles of new trails, three new restrooms and five wildlife viewing areas. But MacAdams said that, while those improvements are welcomed, the $453-million plan still wouldn’t do L.A.’s waterway justice.

“The Corps wants to get out on the cheap, so they aren’t even paying attention to their own study,” MacAdams said. “Alternative 13 only restores minimal habitat.”

But MacAdams is optimistic about getting something better. He said the growing list of supporters for a larger project now includes U.S. Senators Barbara Boxer and Dianne Feinstein, along with local members of the House of Representatives and Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi. But while Mayor Garcetti and other supporters are pushing for Alternative 20, the project faces an uphill battle in Congress, where budgetary constraints and partisan gridlock are the order of the day. On Tuesday, Feinstein acknowledged that it may be necessary to find a middle ground. (Another option in the feasibility study, Alternative 16, splits the difference between the two plans—including some, but not all, of the improvements for a price tag of $840 million.)

“Even if we don’t get what we want and have to settle for [Alternative] 13 or 16, it begins to take back the river, and that’s a journey that’s going to take a long time,” MacAdams said.

The L.A. River was encased in concrete after repeated flooding devastated parts of the city in the early part of the 20th century. The massive project stopped the flooding, but also destroyed miles of habitat and transformed the river into an eyesore, driving local residents from its banks and making it the butt of jokes on a national level.

In recent years, interest in revitalizing the river has surged. In 2010, the Environmental Protection Agency declared it a “navigable waterway,” paving the way for enforcement of the Clean Water Act within its 834-square-mile watershed. And just this past summer, a kayaking pilot program experimented with literally navigating the river.

All three options under consideration would return 13 currently-underground streams to the surface, create new habitat and restore, at least partially, three adjacent properties—Taylor Yard, Piggyback Yard and Pollywog Parcel. Alternatives 16 and 20 also would add terracing along stretches of the riverbank, remove some of the concrete and create new wetlands. However, only Alternative 20 would connect the river to L.A. State Historic Park, bring large-scale restoration to the river’s confluence with the Verdugo Wash and widen part of the river bed.

For the county, Alternative 20 would be a big help in managing the watershed, said Mark Pestrella, an assistant director for the Department of Public Works. While the Army Corps is tasked with taking care of the stretch of river where the project would occur, the county Flood Control District manages other sections of the waterway. Bringing more people to the river would induce them to help take care of it and support its continued improvement, Pestrella said. The restoration project would join an ongoing evolution of the urban river that stretches back to the 1980s and includes the 1992 Los Angeles River Master Plan, the first study to take a comprehensive look at the entire length of the river to look for opportunities for recreation, restoration of habitat and creation of open space.

“We are midstream—the County sees this as the next step,” Pestrella said. “We’ve done hundreds of millions of dollars in L.A. River Master Plan improvements already.”

Because Alternative 20 adds new park space and improves connections to neighboring communities, county officials and other supporters say it would draw more people seeking recreation opportunities.

“Until people actually reach out and touch the environment and nature, they don’t know what they don’t have,” Pestrella said. “Once people make an investment in it that improves their life, they just want more of it. We’re funded by the public so we need that buying in—we need people to turn toward the river.”

Posted 10/31/13

Market’s got a brand new bag

October 15, 2013

Attention, Grand Park shoppers: plastic bags are no longer on the menu at your weekly farmer’s market.

On Tuesday, merchants started handing out paper bags with purchases, and park employees distributed more than a hundred free, reusable tote bags to shoppers who agreed to fill out a short, six-item questionnaire about their market experience.

“We ran out in the first two hours,” said Karen Tran, one of two workers handing out the totes.

The market’s manager, Susan Hutchinson, said some merchants had initially expressed concerns that paper bags would be more expensive than plastic and would not hold up as well to potentially messy items, like ripe peaches and plums.

Both fears proved to be unfounded when vendors transitioned from Styrofoam clamshell containers to cardboard, and she expects an equally smooth transition to the new bags, which are required under county law and will be mandated by the city as well beginning Jan. 1, Hutchinson said.

“The reality is it’s not such a big deal,” Hutchinson said. “People adapt.” She’s hoping that customers’ adaptation will include remembering to bring their own reusable bags to the market, which runs from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. on Tuesdays.

On Day 1, the lunch time crowd seemed to welcome the change.

“I think it’s great,” said county employee Nyla Jefferson, carrying two paper bags loaded with apples, peaches, plums and blueberries.

LAPD Detective Ron Walker held one of the free tote bags as he waited for his apple feta salad to be prepared. He said he was glad to see the bag policy change.

“Even supermarkets are charging for bags now,” he said.

Posted 10/15/13

Betting on a shore thing

September 19, 2013

With plastic bag bans taking hold across the state, officials say our beaches are becoming beneficiaries.

At the end of each summer, the beach gets a close-up.

On the annual Coastal Cleanup Day, which occurs again on Saturday, thousands head to beaches and watersheds to pitch in during what’s billed as the largest volunteer event in the world. The junk they collect provides a troubling snapshot of how some of our bad habits can affect the environment.

During last year’s cleanup, a whopping 516,798 pounds of debris was collected statewide. The biggest offender was cigarette butts, accounting for 217,423 pounds, or 42 percent of the total. But plenty of other stuff was collected, too, including 94,182 pounds of food wrappers and containers, 43,783 pounds of plastic bags, 1,159 pounds of condoms, 1,187 pounds of six-pack holders and 508 pounds of syringes. You get the idea.

In L.A. County alone, 43,427 total pounds of debris was picked up last year, despite a volunteer turnout that was significantly reduced by triple-digit temperatures.

Still, the numbers offer a ray of hope. Eben Schwartz, who organizes the statewide volunteer push for the California Coastal Commission, said plastic bags, which take hundreds of years to decompose, are declining in jurisdictions that have enacted restrictions.

“In San Francisco, bags are way down the past couple of years,” Schwartz said.

Bans on single-use plastic bags started in the Bay Area around 2007 and are now banned throughout Alameda County. L.A. County banned plastic bags in 2010, but the ordinance only applied to county facilities and unincorporated areas, representing a small slice of the region’s total population. Other jurisdictions have since followed suit. In June, the City of Los Angeles got on board with an ordinance that will take effect next summer.

“On future cleanup days,” Schwartz predicted, “there’s going to be a whole lot less plastic bags in Los Angeles.”

Officials say that other government measures appear to be having an impact, too, including bans on Styrofoam containers and the installation of storm-drain screens to catch debris. The amount of trash collected statewide during Coastal Cleanup Day 2012 was just 12 pounds per person, down from 19 pounds in 2011, 15 pounds in 2010 and 17 pounds in 2009.

Over the past decade, catch basin screens have been installed in storm drains throughout L.A. County, said Kerjon Lee, spokesperson for the county’s Department of Public Works. The basins block trash from entering inland waterways and reaching the ocean.

Further downstream, Lee said, trash booms are deployed after rain storms to catch debris that has made it down flood channels and rivers. “They are good systems but they are end of the pipe systems,” Lee said of the booms. “It’s kind of a last, valiant effort to prevent debris from entering water bodies.”

Meanwhile, public health initiatives, such as banning smoking on the beach, have also had a positive impact on the on the environment, reducing trash on the sand and in the water, Lee said.

But not everything can be caught before it hits the water, and that’s where Coastal Cleanup Day comes in. The event began in Oregon in 1984. Nine years later, it had entered the Guinness Book of World Records as the “largest garbage collection.” The event has now spread to 35 states and nearly 100 countries. Here in L.A. County, both inland and at the coast, 11,000 volunteers will fan out on foot, on kayaks and even in wetsuits and scuba gear.

Liz Crosson, executive director of Los Angeles Waterkeeper, organizes a yearly scuba cleanup around “Hyperion Pipe,” which sends L.A.’s treated waste water miles out to sea. The structure that holds the pipe in place catches a lot of trash that enters the ocean. “I am amazed at what they pull out of there,” Crosson said. “They get pounds and pounds of plastic bags.”

Heal the Bay has been the lead organization for L.A. County’s Coastal Cleanup Day since 1990. Marissa Maggio is coordinating the event for the nonprofit environmental group.

“You can notice a difference; there’s definitely less debris at certain beaches,” said Maggio, who hopes to inspire people year round. “It would be great if every time you went to the beach, you bring a bucket and glove and pick up a little trash.”

Posted 9/19/13

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink