The Insider

County’s $840 million reform plan

June 17, 2014

The county, which pays millions annually for health care for retirees and their dependents, will save substantially in the years ahead.

In a move expected to save hundreds of millions of dollars in the decades to come, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors on Tuesday approved historic reforms in the way it pays for county retirees’ health care insurance.

County officials said the changes could save $840 million over the course of the next 30 years. Under the plan—which applies to those hired after July 1, not to current workers—the county will reduce the subsidies it provides for retirees to purchase health care insurance. The changes approved by the board also require retirees who are eligible for Medicare to enroll in the federal program; the county subsidy will be applied to a Medicare supplement plan.

The savings are projected be considerable. Currently, the county pays up to $1,953.41 a month to subsidize health care benefits for a retiree and his or her family. Under the new plan, a retiree under the age of 65 would receive an individual monthly subsidy of up to $918.46, which will be reduced to $370.89 once the retiree reaches 65 and can be covered under Medicare. The new plan is based only on individual coverage, but retirees can still purchase insurance for their dependents at their own expense.

“This represents one of the most significant improvements to our retiree health care benefit since the 1980s. It reduces our unfunded liability by 20%,” said William T Fujioka, the county’s chief executive officer. “It speaks to our board’s fiscal responsibility and fiscal discipline, and it’s a move that will help ensure our future financial viability.”

Fujioka said the support of county labor groups had helped make the new retiree health plan a reality.

“They were with us 100%,” Fujioka said. “We went to the table and negotiated this change, and they joined us in presenting this change to our L.A. County retirement board. As a consequence, we got a unanimous vote.”

The county currently pays about $487.8 million a year for retiree health care—with that obligation coming off the top of the budget each year, before other programs are funded.

Taking action now ensures the health of the retiree benefit in the years ahead, Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky said.

“These reforms allow Los Angeles County to continue its leadership role in providing fair and responsible benefits to retirees, in contrast to troubles that have affected many other jurisdictions across the country,” Yaroslavsky said. “Without these changes, our health care program would have faced severe challenges going forward. As it is, we are doing the right thing for future generations of L.A. County employees and taxpayers.”

Posted 6/17/14

A new Dawn at the museum

April 16, 2014

After overseeing high-visibility projects all over the county, Dawn McDivitt is ready for a new challenge.

Want to explore the Dawn McDivitt map of Los Angeles?

Here’s an itinerary, just for starters:

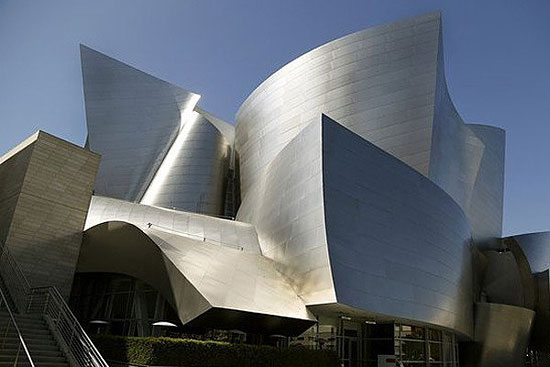

A gleaming architectural gem (Disney Hall), an international symbol of great music (the Hollywood Bowl shell), a splashy Civic Center hot spot (Grand Park), a state-of-the-art medical facility (LAC+USC Medical Center), an imposing lockup on the outskirts of downtown (Twin Towers Jail), even a tarry pond right beside Wilshire Boulevard, complete with prehistoric mammoth figures (the La Brea Tar Pits lake bed.)

Over more than two decades, McDivitt has managed projects to build, rebuild or revamp all of those, along with numerous other L.A. County facilities ranging from fire stations to swimming pools. It’s an extensive body of work that has served untold tens of thousands of residents and visitors from every walk of life.

While her pivotal role in bringing all those projects to fruition may be little known to the general public, around the county Hall of Administration, McDivitt is something of a capital projects rock star, with her exuberant laugh, infectious enthusiasm (a favorite adjective: “fabulous!”) and widely-respected ability to get things done.

But, after helping guide the course of more than $2 billion in projects as a manager in the Chief Executive Office, the 56-year-old McDivitt is about to notch a new destination on her professional map: the county’s venerable Natural History Museum.

On May 1, she becomes the museum’s chief deputy director, serving as its No. 2 executive under president and director Jane Pisano.

“She has worked on so many major cultural projects in the county. She really understands and values public-private partnerships and getting things done,” Pisano said. “She is going to be such a great fit here.”

In addition to the main museum in Exposition Park, McDivitt in her new position also will oversee the Page Museum at the La Brea Tar Pits and the William S. Hart Ranch and Museum in Newhall.

“For me, it’s a time for something new, and moving outside of the comfort zone,” McDivitt said on a recent sunny afternoon as she left her 7th floor office to walk through one of her signature accomplishments, Grand Park. “Especially when you stop and realize you’ve been in a place for 20 years.”

The attraction—and the challenge—will be learning to lead a new team in a new environment with a lot of new responsibilities, from human resources to technology, along with more familiar duties like overseeing projects.

“I’m looking forward to learning…I always thrive on knowledge, anyway. I think if you continue to learn, you continue to expand as a person,” McDivitt said. Plus, she added: “I think it’s going to be a really cool environment to work down there because I absolutely love history.”

Like many Angelenos, McDivitt has early memories of going to the Natural History Museum and the Page as a child. And in her professional capacity, she got the chance to oversee a challenging project on the Page/Tar Pits grounds in 2011 when it turned out that the lake was seeping oil and gas into storm drains when it overflowed.

She supervised the CEO’s staff in managing the effort to install a new underground water purification system and connect the tar pits lake to the city sewers beneath Wilshire Boulevard.

Fix-it operations are nothing new to McDivitt.

“It’s kind of like that little Dutch boy with his fingers in the dike,” she joked. “There are times that I just want to pull my finger out and see what happens!”

She’s kept trouble at bay countless times, perhaps most prominently when glare from the new Disney Hall was found to be reflecting into nearby condominiums and onto the street. The solution: Workers with hand orbitals sanded down part of the surface.

Then there was the discovery of human remains during construction of LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes. After expert consultation, the bodies and artifacts were reburied in a special memorial garden at the site.

Even Grand Park needed some emergency trouble-shooting after its inaugural event—a big participatory dance-fest—reduced the Performance Lawn to a “mud pit.” (A new underground drainage system is now in place to prevent a repeat performance.)

McDivitt said she has learned how to listen first and let solutions emerge from dialogue.

“Staying calm is a really good challenge to me since I’m Irish,” she said. “So I tend to want to react and solve a problem right off the bat, and think of a solution before I actually listen to everything. My sisters tend to say to me, ‘OK, I’m calling to talk to you and I only want you to listen. Don’t solve the problem. I want you to listen.’ “

McDivitt said she is leaving behind a “great team” to carry on the capital project work, including upcoming phases of the Grand Avenue Project. (A Frank Gehry-designed development to be built across from his acclaimed Disney Hall is expected to come before the Board of Supervisors later this month, before McDivitt departs.)

But she’ll be taking with her something rare and precious: the opportunity to watch in delight as her work took on a life of its own.

“Look how much it’s being used,” she said as she strolled through Grand Park, children frolicking in the fountain and grownups lingering over lattes at café tables. “This is fabulous! That just feels so exhilarating—especially when you’re in the public sector.”

Posted 4/16/14

Defenders mark a century of L.A. law

January 19, 2014

In this 1963 photo, Public Defender Kathryn McDonald confers with client Gregory Powell (left), who was accused with Jimmy Lee Smith in the "Onion Field" killing of LAPD officer Ian Cambell.

In the early 1880s, an Italian immigrant in San Francisco was charged with trying to collect $500 in insurance by torching his house on Telegraph Hill. The man was innocent but could not afford a decent attorney, and when his trial date rolled around, his lawyer didn’t show.

So the judge, as judges did then, went into the hallway and ordered the first lawyer he saw to represent the defendant. This didn’t bode well, since most court-appointed defense lawyers at the time were not only unpaid but also incompetent.

The lawyer—Clara Shortridge Foltz—was, in fact, just out of law school. But she won the case and used it as Exhibit A in a national push that led to the opening of the nation’s first public defender’s office in 1914 in Los Angeles.

One hundred years later, the Public Defender’s Office of Los Angeles County is marking its centennial anniversary. Some 700 attorneys work there now—more than at any criminal defense firm in the nation—along with hundreds of investigators, paralegals, psychiatric social workers and support staff. Last fiscal year, they defended clients in more than 400,000 felony and misdemeanor cases, not counting the thousands more defendants in juvenile delinquency and mental health courts.

Like Foltz, they occasionally make history. And, like Foltz, they tend not to become particularly famous. (In 2001, when the criminal courthouse downtown was renamed in her honor, the Los Angeles Times noted “a chorus of people saying: ‘Clara Who?’”)

“We usually pick up cases because nobody else is there,” says Alan Simon, a now-retired public defender bureau chief who spent five mostly unsung years representing the Hillside Strangler, Kenneth Bianchi.

“But most of the great names in public defense are not the ones that you see in the headlines. Charlie Gessler was probably one of the best defense lawyers ever. Do you know who he is? Probably not.”

Deputy Public Defenders Bernadette Everman and Dave Meyer at arraignment of "Night Stalker" Richard Ramirez.

Less obscure are some of the names of the clients represented over the years by the department. The Night Stalker had a public defender. So did the Onion Field killers and members of the Manson and Menendez families. Public defenders played a key role in uncovering the Rampart scandal at LAPD in the 1990s, and handled the crush of cases filed in the wake of both the Watts Riots and the L.A. Riots.

Most of the office’s clients, however, are the kinds of people to whom society tends to pay little attention—the impoverished, the downtrodden, the lost, the addicted, the difficult.

“It’s a calling,” says Public Defender Ron Brown, who has spent 33 years in the office, where turnover for reasons other than retirement averages a miniscule 2 percent a year.

“Our clients aren’t always nice people,” Brown says. “But somebody has to defend them, and vigorously defend them, in order for justice to be done. So what we do is about protecting peoples’ constitutional rights, and people who work here find that this is a place where they can do God’s work, as corny as that may sound.”

As integral as the Public Defender’s Office now is to the legal system, it was a radical notion when it began. It arose from decades of lobbying by Foltz, whose long list of accomplishments included being the first female lawyer in California. With fellow suffragettes and Progressive allies, she sought to balance the odds in the late 1800s against impoverished defendants who were often railroaded by ambitious prosecutors and judges, even though they were supposed to be presumed innocent.

At the time, the state prosecuted people suspected of criminal wrongdoing, but didn’t underwrite any of their defense costs. A judge could appoint a lawyer to represent a pauper. But the court-appointed attorney, who was duty-bound to take the assignment, had to work without pay, or pro bono.

As a result, few competent lawyers made themselves available for such work. Instead, judges typically drew from the lowest ranks of the courthouse pecking order, often strolling out into the hallways and grabbing whoever happened to be around.

Foltz was outraged by the situation. A lawyer’s daughter, she had turned to the law to support herself after her husband deserted her and their five children. She had a soft spot for the poor.

She also had a knack for agitation: When she learned that only white males could become lawyers in California, she hounded the governor into signing landmark legislation to abolish the inequality. When she couldn’t’ get into law school, she sued for admission. Now, pressed into action on behalf of poor clients, she believed the time had come for lawyers like her to be able to make a living.

So she began agitating for legal reforms that would guarantee a paid defense and balance the odds against the defendant. According to a definitive biography of Foltz by retired Stanford law professor Barbara Babcock, she spent three decades campaigning in state legislatures and drafting model statutes before a political tide of Progressives and women—who had just gotten the vote here—led to success in California.

By then, Foltz was working as a deputy district attorney in Los Angeles County, another first for a woman, and was an influential political voice, both nationally and here. In November 1912, Los Angeles County voters approved a charter that included the creation of the Office of the Public Defender, and the following year, it was ratified by the state legislature.

After a competitive exam, the Board of Supervisors appointed Walton J. Wood, a Los Angeles deputy city attorney, as the first public defender in the nation. The office opened on Jan. 9, 1914.

Over the years, according to Public Defender Brown, the office’s focus has changed with the societal landscape.

“In the past, we looked exclusively at winning—at getting the guy out and moving on,” he says. “The thought was that we’re lawyers, not social workers. But in fact, a good lawyer really is a kind of social worker. You end up getting involved with everything from housing to mental health needs.”

To that end, the office now works closely with social services in the county, from children’s services to mental health. It also has helped pioneer the use of specialized courts for addicts, veterans, the mentally ill and women, and has become involved in communities with programs like Parks After Dark.

And as it heads into its next century, he says, the department has added to its diversity in ways that would probably please the suffragette who made it happen: More than half of the lawyers—from trial lawyers to managers—are female now.

Clara Shortridge Foltz's groundbreaking activism led to the creation of L.A. County's Public Defender's Office in 1914, the first of its kind in the nation.

Posted 2/21/14

Heroes in hardhats

January 8, 2014

They have rescued small children from oncoming traffic. They have brought a victim of attempted murder back from the brink of death. They have braved rising floodwaters and raging house fires. Last month, they dragged an unconscious driver from a burning SUV seconds before the truck’s gas tank exploded.

Not all first responders are sheriff’s deputies or firefighters. Some also find themselves in the occasional life-and-death situation while minding the county’s infrastructure at the Department of Public Works.

Emergency response has been among DPW’s core services since 1985 when the department was created, though the public tends to be more familiar with the department’s work in engineering, flood control and road maintenance. DPW maintains a 24-hour emergency operations center, and employees there are trained for disaster.

In fact, over the years, so many DPW hardhats have stepped into the breach so often that after a beloved employee named Kelly Bolor died in Iraq in 2003 while serving as a member of the U.S. Army Reserves in Mosul, the department created an in-house award for valor that has been presented in the wake of a number of incidents.

Since that date, nearly two dozen DPW employees have received the Kelly Bolor Award for heroism of one sort or another, from Ignacio Orozco Jr., who used a county dump truck to head off a potentially fatal car crash on Imperial Highway last year to members of Road Maintenance Division Crew 551, who extinguished a raging house fire in 2011 near their Antelope Valley work site, to Gary Clinton, who used his motorgrader to rescue panicked motorists from a flooded crossing in the high desert in 2005.

“I’ve been with the county for 29 years, and I think we’ve all at one time or another been first responders in some kind of situation,” says Steven Smith, a road maintenance superintendent in Agoura whose crew members, Lowell Johanknecht and Enrique Ramos, are expected to be nominated this year for pulling a woman from a burning SUV on Mulholland Highway on September 18.

Lowell Johanknecht, left, and Enrique Ramos are the latest Public Works heroes. Photo/ Christian Garcia DPW

“If an accident happens and you’re around, you rise to the occasion. This job can be dangerous, too.”

That certainly was the case for the award’s first recipient, Marco Andonaegui, who was replacing traffic signs in 2004 on Topanga Canyon Boulevard near the 101

Freeway when he glanced up and saw a child tumble out of an SUV.

“He was 8 years old and his buckle must have come undone,” says Andonaegui, a 30-year DPW employee who says he still gets chills when he thinks of how close the child came to being hit by oncoming traffic.

“I was alone, going the opposite direction and they were just a couple a cars in front of me.”

Andonaegui scrambled out of his county vehicle, jumped the median and grabbed the child as the SUV drove on, the child’s mother oblivious to what had happened.

“Cars were swerving around us, braking around us, the little boy was crying and crying,” recalls Andonaegui. “I don’t know how the heck I didn’t get hit, let alone the little kid.”

Fifteen minutes later, he says, the mother circled back, frantic.

“She was desperate and grateful, and she must have given me 20 or 30 thank yous, but she was crying so hard, she forgot to ask for my name or give me hers,” he remembers.

It was only afterward, he says, that he learned she had written down the phone number on the back of his county truck and called the department. A father of grown children, he says he never heard from the woman again and still doesn’t know her name or her son’s name, but he still keeps his award plaque in his Lynwood living room.

Dam Operator Gary Elrod says he and his fellow crewmen on the remote San Gabriel Dam compound likewise never heard again from the young man they rescued.

It was early on a Tuesday morning, May 29, 2007, and the seven dam workers, several of whom live on the isolated site high in the San Gabriel Mountains, were starting their day early when Assistant Dam Operator Benny Velasco spotted a body in a drain near the roadside.

“It looked like he’d been attacked at another location, stuffed in the trunk of his car, driven to the entrance area of the San Gabriel Dam in Azusa Canyon and left there for dead,” recalls Elrod. “I personally counted nine stab wounds.”

A 25-year DPW employee who had worked in his youth with an emergency response team in Saudi Arabia, Elrod says he grabbed his blanket and safety gear and started to administer first aid.

As the crew waited for paramedics to arrive, Elrod tried to keep the barely coherent victim from falling into unconsciousness.

“This isn’t your time,” he remembers repeating to the young man as the sun rose over the mountains. In the hospital, Elrod says, the victim, who was from Whittier, refused to name his attacker, and the case was still unsolved three months later when he stopped asking about it.

“He denied everything he’d said to me when the sheriff questioned him later,” says Elrod. “All I know is, he’s out there somewhere with a horror story to tell his children and he’s lucky we came along when we did.”

The workers say they don’t mind that the recipients of their help often have no idea who they are or what department they work for.

“It makes you feel good just to be able to help,” says Johanknecht, the 23-year-old road laborer who pulled the woman from the burning truck last month on Mulholland Highway near Las Virgenes Road.

Johanknecht, who lives in Redondo Beach, says he had finished his shift at the Road Maintenance Division’s Yard 339 near Agoura Hills and was heading off to meet his girlfriend at their community college when he noticed the plume of smoke and the overturned Chevrolet Suburban. Pulling over on his motorcycle, he called 911 and ran toward the crash site.

“The 911 operator asked if anyone was in the car, and I said yeah, there’s a lady in the driver’s seat,” he remembers. “Right then, an older gentleman on a bicycle came up the hill and said, ‘What do you want to do?’ And I said, ‘Get her out!’”

Just then, he says, Ramos pulled over, having seen the skid marks, the smoke and his coworker’s abandoned Suzuki DR650. Working together, the three wrestled the woman, who appeared to be in her 40s, out of the black SUV and back toward the road’s shoulder.

“She was panicked and freaking out and pushing us away and in shock,” Johanknecht says, “and smoke was engulfing the car and all the air bags had deployed and blocked all the windows.”

As they carried the woman to safety, the SUV’s gas tank exploded, igniting a brushfire that engulfed nearly two acres before two Super Scoopers and four water-dropping helicopters were called in to contain it. Los Angeles County Fire Inspector Scott Miller could not release the woman’s name, but said she was transported to a local hospital. Ramos and Johanknecht say they never found out who she was and haven’t heard from her.

Johanknecht says his parents and girlfriend were “worried and proud at the same time” when they heard what happened, and wishes the crash victim—whoever she is—a speedy recovery.

“You never expect this, but you never know—we work out here in no man’s land, and a lot of things happen,” he says. “I just hope that someone would do me the same favor if something like that ever happens to me.”

Posted 10/15/13

Board votes to restore cross to seal

January 8, 2014

The current county seal, revised in 2004, will be changed again to include a cross atop the mission.

Reopening a long-running and divisive controversy, the Board of Supervisors this week voted to once again place a cross on the Los Angeles County seal.

The action came nearly a decade after the board agreed to remove the Christian symbol under threat of a legal challenge by the American Civil Liberties Union. The county spent hundreds of thousands of dollars after that 2004 decision to replace the seal with a redesigned version that now appears throughout its facilities and on items ranging from business cards and badges to uniforms and vehicles.

The impetus for the board’s about-face this week was a motion by Supervisors Michael D. Antonovich and Don Knabe, who argued that the current seal’s depiction of the San Gabriel Mission without a cross is “artistically and architecturally inaccurate.” Although the cross was removed from the mission during retrofitting following the Whittier Narrows earthquake, their motion said, it has since been restored to the structure and the county seal should reflect that.

Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas joined Antonovich and Knabe in voting to bring back the cross. Supervisors Gloria Molina and Zev Yaroslavsky voted against the measure.

Although the motion made no mention of religion, Yaroslavsky said the cross is the principal symbol of one particular faith, and noted that there is extensive legal precedent barring its incorporation into the seal on Constitutional grounds.

“The court cases have made it very clear that the use of a symbol, the principal symbol of any religion on a government seal, is unconstitutional,” Yaroslavsky said.

“And this is not just about history,” he added. “It’s about the cross. To say anything different would be really somewhat disingenuous…There are a hundred ways we could depict history. But the one that’s been chosen here is the cross.”

The county seal currently in use replaced a 1957 version designed by the late Supervisor Kenneth Hahn and drawn by the artist Millard Sheets. Hahn said at the time that the seal was intended to depict “the cultural and educational and the religious life of this county.” Featured on the seal, in addition to the cross, were images including the Hollywood Bowl, a Spanish galleon, a tuna, a prize-winning Guernsey cow named Pearlette, several oil derricks and the goddess Pomona carrying fruit. The redesigned seal eliminated the cross, the derricks and the goddess but added an image of a mission (without a cross) and a Native American woman.

The 2004 decision to drop the cross prompted an uproar, with nearly 1,000 people gathering outside the Hall of Administration on the day of the Board of Supervisors’ vote, some with signs calling the ACLU the “Annihilation of Christian Liberties Union.” Hahn’s children, then-Mayor James Hahn and then-Councilwoman Janice Hahn, argued in favor of keeping the symbol on the county seal.

Yaroslavsky, however, said at the time he was willing to make an unpopular decision if it was the right thing to do: “The First Amendment is not a popularity contest.”

At Tuesday’s meeting, he once again argued against including a religious symbol on a government seal, but this time was on the losing end of the vote. Before the board’s 3-2 decision, Yaroslavsky predicted the county would face, and lose, a legal challenge—particularly since it would be restoring a symbol it had removed after questions were raised about its constitutionality.

That point was echoed by Peter J. Eliasberg, legal director of the ACLU of Southern California, who said reincorporating the cross into the county seal would violate both state and U.S. constitutions. He also said that the separation of church and state has helped to strengthen religious activity in the United States, not to diminish it.

“The ACLU strongly believes that religion has flourished in this country, perhaps more than any other, and religious pluralism has flourished because the government does not favor or denigrate any particular religion,” he said. “Adding a sectarian religious symbol to the county seal, the preeminent symbol of one particular religion, runs against that grain.”

After the meeting, Eliasberg would not say whether his organization plans to file a lawsuit.

While Eliasberg spoke against the motion, several others supported it, including a resident of Altadena who said: “There’s nothing unconstitutional about having an historical reference to the role of religion in the formation of the nation…None of this has really anything to do with the Board of Supervisors or anyone else promoting religion. We’re just accurately depicting our cultural heritage in history.”

Posted 1/8/14

Grand Park comes of age

October 3, 2013

They built it. And they came.

This week marks the one-year anniversary of downtown’s Grand Park, a four-block expanse that has provided a jolt to Los Angeles’ Civic Center for reasons well beyond its hot-pink furniture.

Since its dedication last October, the 12-acre park between the Music Center and City Hall has drawn tens of thousands visitors for events big and small, from a Fourth of July extravaganza to daily yoga classes. Although the big-city development around it continues to be vigorously debated, the park itself has proven to be an intimately scaled magnet for families and children. The “splash pad” at the Arthur J. Will Memorial Fountain, in particular, has drawn knee-high youngsters and their parents from across the region.

“It’s just as serene and beautiful as I expected,” said Kesha Barkulis, who, on a recent and sparkling autumn weekday, was following her drenched and teetering 9-month-old daughter, Luna, as she navigated the 79 gentle water jets of the fountain.

It was their first visit to Grand Park, one that Barkulis said she’d wanted to make all summer, ever since reading about the ¼-inch-deep pool on a website aimed at moms seeking kid-friendly outings. They had taken the Red Line subway from North Hollywood to the Civic Center station, located just steps away from the fountain, which has become a popular venue for toddler birthday parties now.

For decades, the area formerly known as the “Civic Center Mall” was largely hidden by concrete parking ramps and two blockish government buildings—the Superior Court and Los Angeles County Hall of Administration. As a result, the mall and its 1960s-era fountain ended up being used mostly as an outdoor break area for bureaucrats and jurors.

But after a $56-million privately-financed makeover, which was required as part of the approval process for commercial development along Grand Avenue, the park is now generating crowds—and buzz—through a mix of programming experiments overseen by the Music Center.

The Fourth of July event, for example, drew an estimated 10,000 people, according to Grand Park Programming Director Julia Diamond. Thousands of people, she said, also have shown up for dance events and a movie series featuring such family fare as “ET” and “The Never Ending Story.” Last Sunday, 2,000 music fans gathered on a Grand Park lawn to watch the first simulcast of a Walt Disney Concert Hall performance, which featured jazz great Herbie Hancock.

Not bad for Year One.

“People think of Angelenos as wanting to celebrate privately,” Diamond said. “But people in L.A. are game for sharing.”

The park, which she called a “cultural and civic space with no walls,” has tapped into that growing hunger for collective experiences, exemplified by the widely popular CicLAvia events.

One key to the park’s early success, Diamond said, is that thousands of people in offices and lofts downtown “have actually shown a large appetite for diversion and entertainment in the middle of the day, uniting around something that speaks to a part of themselves outside of their work lives.” Besides lunchtime yoga and informational fairs on such topics as green transportation and public health, the mid-day programming has included a weekly farmer’s market and concerts ranging from Latin jazz to classical music to pop.

Diamond said she’s also been struck by the ethnic and economic diversity of the visitors—a result, she suggested, of having a park without a strong neighborhood history or existing identity. “This gives the park a lot of freedom to be whatever people want it to be,” she said.

Still, not everything’s gone as the programmers had hoped. One of the biggest first-year challenges, Diamond said, has been to get the downtown workers to become an after-hours crowd. “They get into their cars and drive away,” she said, adding: “If you gave people a reason to stay, they would. We haven’t found that reason yet.” (One possible reason: Grand Park’s official 1st birthday bash, which takes place from 7 p.m.-10 p.m. on Thursday, Oct. 10, and features free entertainment on the Performance Lawn.)

Diamond said Grand Park programmers and marketers also have been stymied by the nature of downtown itself, which she described as “sort of like the Balkans.” The farther away from Grand Park people work, such as in the Bunker Hill area, the harder they are to engage. Downtowners, she said, “tend to stay in their micro-community.”

Diamond’s anniversary wish for the next year?

“I want everyone in Los Angeles to know about Grand Park,” she declared. “A year ago, we didn’t exist. I want that name to have instant recognition as an amazing place.”

Grand Park's music events have proven particularly successful in drawing crowds during the first year.

Posted 10/3/13

Dog law gets some extra bite

September 6, 2013

Dogs that attack horses, cows and other livestock will soon be designated as "potentially dangerous."

Spurred by the recent fatal pit bull attack on a 63-year Antelope Valley woman, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors on Tuesday voted to make it easier to take action against lethal canines by broadening the legal definition of a “potentially dangerous dog.”

The new definition, particularly significant in rural parts of the county, allows serious attacks on livestock—including horses, cows, alpacas, chickens and rabbits—to qualify a dog as “potentially dangerous” under county animal control laws. The current ordinance authorizes that classification only if the dog has moderately injured a person, forced a person to take defensive action more than once in 36 months or severely injured or killed a dog or a cat.

Restrictions for a potentially dangerous dog can range from requiring the animal to be leashed and muzzled in public to mandating that the owner take out liability insurance and keep the dog inside or in a secure, county-inspected yard.

Animal control officers contend that the amended criteria might have made a life-and-death difference in the case of Pamela Devitt, who was jogging in the Antelope Valley community of Littlerock in May when four pit bulls attacked her on the street. Fatally mauled, Devitt died in an ambulance on the way to the hospital. The owner, 29-year-old Alex Jackson, is in custody and facing homicide charges.

Of the eight dogs confiscated from his home, four were euthanized, said Animal Care and Control Director Marcia Mayeda. The other four—two pit bulls, a Labrador-collie mix and an Australian heeler mix—were taken in by a rescue group and placed in homes.

“We’d had complaints about these dogs and had been out to the house twice,” Mayeda said. But the dogs were not in sight, she said, and the owner had insisted the complaints involved strays, not his dogs.

Just three weeks before Devitt’s death, however, a woman had complained that the pit bulls had come after her and her horse, Mayeda said. She said the complaint was serious enough that the department had asked her to complete a sworn affidavit.

“We were still waiting for her statement when the attack on Mrs. Devitt happened,” Mayeda said. “Had we had this law on the books, we could have just declared those dogs potentially dangerous and restricted them.”

The new definition is part of an intensified county focus on the problem of dangerous dogs. About one call in ten to the Department of Animal Care and Control—about 10,000 annually—involve dogs that are aggressive and biting. Packs of abandoned dogs have become an increasingly vexing issue in the high desert and other semi-rural areas. Earlier this year, the Board of Supervisors approved $3.5 million in new spending on animal control.

So far this year, Mayeda said, the county has conducted more than 400 hearings to determine whether a dog is vicious or potentially dangerous. Most of those cases, she said, ended with the dog being restricted. More than half have involved pit bulls.

Posted 9/6/13

Review ordered of rehab rip-offs

August 14, 2013

An investigative series that revealed corruption in the rehab industry has prompted state and county probes.

Faced with reports of rampant fraud in California’s taxpayer-funded alcohol and drug programs for the poor, the Board of Supervisors on Tuesday ordered an examination of whether “regulatory conflict and confusion” between the state and county may have opened the door to unscrupulous operators.

The board’s action, based on a motion by Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, comes in the wake of a year-long investigation by CNN and the Center for Investigative Reporting, which found that during the past two fiscal years in California, $94 million in public funds had been paid to clinics showing “signs of deception or questionable billing.”

Among other things, the “Rehab Racket” series revealed that clinics allegedly submitted bills for fake clients, paid people to sign up for treatment that would be reimbursed by taxpayers and pressured staffers to forge paperwork.

The Drug Medi-Cal program—now the target of a state investigation—is funded through federal and state monies that, in Los Angeles County, are mostly controlled by the Public Health Department’s Substance Abuse Prevention and Control division. The program is jointly administered by the state and county.

During the last fiscal year, L.A. County contracted with 143 providers serving 30,000 clients. Earlier this month, as part of the state’s renewed scrutiny of the Drug Medi-Cal program, funding was cut to nearly 50 agencies statewide that had been suspended from doing business, many of them in Los Angeles County, home to the largest number of these treatment clinics.

Yaroslavsky’s motion aims to sort out the shifting and unclear responsibilities between the state and county that for years have plagued administration and oversight of the program, which is expected to grow as more individuals qualify for Medi-Cal under federal health care reform.

“It is simply unacceptable for a program of such financial magnitude and critical importance to the public’s health to be undermined by bureaucratic confusion and left vulnerable to scammers,” Yaroslavsky said after Tuesday’s board meeting.

To that end, Yaroslavsky’s motion directs the auditor-controller and county counsel to determine, among other things, the county’s legal authority to audit and terminate contracts with Drug Medi-Cal providers, as well provide an analysis of the state’s responsibilities. The board also approved an amendment by Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas ordering the public health department and county lawyers to create a plan that helps patients avoid harmful disruptions in their care as the result of recent clinic suspensions.

Posted 8/14/13

Bringing star power to mental health

July 9, 2013

“Profiles of Hope” lets celebrities like producer/director Paris Barclay share how they overcame emotional pain.

It started as a handful of inspirational stories, shared by a few brave volunteers—how this one found help for depression, or how that one dealt with the fear of being labeled “mentally ill.”

Three years later, “Profiles of Hope,” the Department of Mental Health’s online video series, has become an unlikely hit as a public health campaign. Celebrities such as Rick Springfield, Mariel Hemingway and Paris Barclay are sharing their personal stories. Last year, it won a local Emmy in the information/public affairs series category. And on Thursday, the mental health department announced that 60-second versions of the videos have been nominated in this year’s public service announcement category. Meanwhile, a half-hour show comprised of the segments just wrapped its second season on KLCS-TV, the Los Angeles Unified School District’s public television station. And most recently, “Profiles of Hope” has been discussed as a training tool for counselors in the Cal State University system.

“A lot of people have sent emails about how much this has moved them,” says the acclaimed Barclay, who directed and produced much of the award-winning HBO series, “In Treatment.” “More importantly, they’ve also shared their own stories, which is the real goal—to start the conversation. One person reveals what’s happened to them, and another person comes back with their story. It’s part of the human process, the circle of revelation.”

The Department of Mental Health’s public affairs director, Kathleen Piché, said the goal of the videos is “to bust the stigma of mental illness, and not just by hearing from providers and clinics and the usual suspects.” The segments came about in 2010, she says, shortly after the creation of the Los Angeles County Channel. “They asked us if we wanted to do some programming,” Piché recalls.

At the time, she says, the Department of Mental Health was looking for new ways to help people overcome the shame and fear that often accompanies emotional and psychological problems.

“A lot of people say they resist getting help because they’re afraid of how others will see them,” Piché says. “But the earlier people get help, the better their outcomes, and right now, the average length of time from the time people first get symptoms to the time they get help is about 10 years.”

Piché says she initially saw the videos as a series of “day in the life” documentaries that would help viewers realize how many people suffer from some form or another of mental illness. Eventually, she settled on shorter, more intimate testimonials. “There are obviously issues about privacy,” she says. “But there are also people who want to talk about it.”

The department already had an informal speakers roster, as did the National Alliance on Mental Illness, she noted, and after a few calls, she found three current or former department clients willing to share their stories.

Myra Kanter, a nurse and patient’s rights advocate, spoke about her lifelong struggle with depression. Isaiah Hinnerichs, a client at the time in a county program for transitional-aged foster youth, talked about the mental health care that helped lift him out of homelessness. Gary Gougis, now a peer advocate at the Department of Mental Heath, talked about the panic attacks that for years had crippled his ability to function.

“At the time,” Piché says, “nobody knew how impactful they would be.”

Since then, she says, more than a dozen Profiles of Hope have been produced, featuring testimonials from people as disparate as a champion boxer, a combat veteran and a gay Vietnamese refugee. Most popular, however, have been the testimonials of celebrities talking about the ways that they’ve been helped by good mental health care.

Actress Mariette Hartley discusses her family history of suicide and alcoholism. Maurice Benard of “General Hospital” talks about managing his bipolar disorder. Robert David Hall of “CSI: Crime Scene Investigation” talks about how he summoned the emotional strength to rebuild his life after both his legs were amputated in the wake of a car crash. Rock musician Springfield shares his story of overcoming depression.

In addition to the 10-minute taped interviews, which are available on Facebook, YouTube, the County Channel and the DMH web site, shorter versions are being aired as public service announcements.

The spots, which initially were paid for by the County Channel, now are underwritten by funds from the Mental Health Services Act, which taxes income over $1 million to support mental health programs. Each testimonial costs about $13,000 to produce, says Piché, who’s been assisted by DMH Public Information Officer Karen Zarsadiaz-Ige.

But to their audiences, the spots are priceless.

“I think Profiles of Hope was so amazing,” one viewer recently wrote to the department, conveying a special thanks to Barclay for sharing the story of his battle with depression and alcohol. “Recently I recovered from a depressive episode.”

“Rick, thank you for this. THANK YOU,” another commented on Springfield’s YouTube public service announcement.

Next up, Piché hopes, will be a series of interviews with well-known people in politics, sports and public service. Meanwhile, Araceli Esparza, who coordinates Mental Health Services Act programs for the California State University system, says the videos are under consideration as a mental health resource for trainings and workshops on the system’s 23 campuses.

“This just keeps growing,” Piché says. “But I think people are willing to do this because they know that it works.”

In rock musician Rick Springfield's video, he reveals his battles with depression and suicidal thoughts.

Posted 6/20/13

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink