Alt Trans

Bike-sharing gears up

October 24, 2013

A regional bicycle-sharing program finally appears to be getting onto the fast track in Los Angeles County.

Metro’s Board of Directors on Thursday voted to begin the process of determining how a program would be structured here, including how best to solicit bids from companies interested in running it.

The board instructed Metro staff to get to work on the nuts and bolts of the issue next month, with a report due back in January on how best to proceed.

That report should include an analysis of how the program might be rolled out in phases, based on things like “existing bicycle infrastructure, existing advertising policies, current ridership trends, and transit station locations,” according to a motion by L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti, supervisors Zev Yaroslavsky and Don Knabe, and two other Metro directors, Mike Bonin and Pam O’Connor.

Bike-sharing has become increasingly common in European cities over the past two decades, and is enjoying a surge of popularity in some U.S. cities as well. The motion cited programs in Chicago, Denver, Minneapolis, New York and in the San Francisco region, where “Bay Area Bike Share” launched earlier this year.

But in Los Angeles—despite the board’s long-running desire to implement a bike-share program here—there have been some bumps in the road.

For example, a plan backed by former L.A. Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, which would have created a bike-sharing network within the city of Los Angeles, foundered when it turned out that the operating company’s plan to sell advertising on its kiosks was precluded by some existing city contracts.

“The Los Angeles region has seen a variety of bicycle share efforts, but none have taken hold because of a lack of regional coordination,” the motion noted.

In light of that, the Metro board also voted to support Santa Monica, which has received a grant to create its own bike-share system, in its efforts to obtain an extension on that funding so that its project can be built in tandem with the regional whole.

As the region’s transit network grows, a bike-sharing program aims to make it easier for public transportation commuters to take the bus, train or subway to get close to their destination, then grab a rental bicycle from fleets strategically located at key stations to conquer the final leg.

Finally, in a sign of the times for a changing Los Angeles region, the motion adopted Thursday also, for the first time, makes supporting bicycling as a “formal transportation mode” an official part of Metro policy.

Eric Bruins, planning and policy director for the Los Angeles County Bicycle Commission, welcomed the board’s action. He said it was understandable that it had taken so long for development of a regional bike-share program here, given the sprawling and complex nature of Los Angeles County and the need to come up with viable business models for this area.

After years of trying, is this time the charm? Bruins raised his crossed fingers and smiled.

Posted 10/24/13

New law puts bike czar in rider’s seat

September 26, 2013

Senior bike coordinator Michelle Mowery has seen a sea change in attitudes about biking in Los Angeles.

You’ve got to hand it to Michelle Mowery. For two decades, she’s persevered, holding the job of “bicycle coordinator” in the nation’s most car crazy city. “A candle in the wind,” she calls herself. Make that a hard-blowing headwind.

But now, almost overnight, Mowery’s mandate has found a powerful constituency in City Hall and on the roads, giving her once-invisible position in the Los Angeles City Department of Transportation rising stature.

“We’ve put in more bike lanes in the past two years than during my entire career here,” she says. “We have a lot of work to do, but we’re getting stuff done.”

The latest achievement came this week, when Gov. Jerry Brown signed a law requiring California motorists to stay at least 3 feet away from cyclists when passing—a requirement already in effect in 22 other states. Four earlier versions of the measure had died because of various safety and liability concerns.

When Mowery heard the news on Monday, she says one word came to mind: “Finally.” For years, she had championed such a law, alongside elected officials in Los Angeles and bicycle advocates statewide. She praises the measure as “a start and an acknowledgement that cyclists need that little bit of space to stay safe.” It will take effect next September.

When Mowery heard the news on Monday, she says one word came to mind: “Finally.” For years, she had championed such a law, alongside elected officials in Los Angeles and bicycle advocates statewide. She praises the measure as “a start and an acknowledgement that cyclists need that little bit of space to stay safe.” It will take effect next September.

According to the California Bicycle Coalition, which launched a “Give Me 3” campaign with Los Angeles advocates to give visibility to the issue, passing-from-behind collisions are the state’s leading cause of bicyclist fatalities. In fact, Mowery says, a galvanizing moment in the long effort to win passage of a buffer zone for cyclists came in 2006, after popular UC Santa Barbara triathlete Kendra Payne was struck and killed by an asphalt truck that tried to pass her on a sharply-curving road.

Mowery says existing California law simply states that drivers must keep a “safe distance” when passing cyclists, a subjective standard. Now, she says, law enforcement has been given a specific tool to cite motorists who invade a rider’s legal space. Even if police don’t make enforcement a top priority, the legislation’s educational value alone could save lives, says Mowery, a lifelong cyclist who’s now 54. She added that this is especially true in Los Angeles, where riders often need more room to dodge bad pavement conditions. “They’re not always able to ride in a straight line,” she says.

Mowery attributes the growing clout of cyclists to shifting demographics. She says that when baby-boomers like her learned to drive, the region’s freeways were new “and wide open. It was the land of opportunity for cars.” These days, however, the under-30-crowd is driving less, while increasing numbers of teenagers are deciding not to even get drivers licenses.

“They see people sitting in traffic and it doesn’t look like fun,” Mowery says.

Eric Bruins, planning and policy director of the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition, agrees, calling this “a golden era for bikes.” The new buffer-zone law, he says, is a “huge” step forward. “For us on the street, this is something we encounter every single day. Everybody just needs a better understanding of what it means to pass safely, and that’s what this law provides.”

Bruins credits Mowery with being a leading force behind the new law through her advocacy in Los Angeles and as a member of statewide cycling organizations. “I don’t think the bike community has understood what a quiet champion she has been…She’s been trying to get this [law] passed forever.”

Bruins says that, for years, Mowery had been a controversial figure, the public face of City Hall recalcitrance to demands for more bike friendly streets. But now, with the growing influence of Los Angeles cyclists, Bruins says, the city’s bike boss is riding high.

Says Bruins: “She is finally empowered to do her job.”

Posted 9/26/13

Finding foot room at CicLAvia

June 6, 2013

Deborah Murphy’s first experience with CicLAvia was no smooth ride. She was walking her Jack Russell terrier down the sidewalk in East Hollywood when she decided to make a move to the car-free streets.

“Get out of the road with your dog, lady—this is for cyclists, stay off the street,” she remembers someone yelling.

When the next CicLAvia brought more shout-downs, the long-time pedestrian advocate and founder of Los Angeles Walks decided to form WalkLAvia, a group aimed at staking pedestrians’ claim to a share of the roads during the events.

“This is an open streets event and people should be out there walking or on bikes or doing cartwheels or whatever they want to do,” Murphy said.

No one would love to see that more than CicLAvia’s organizers, who’ve been pushing for that kind of inclusivity from the beginning. To make that point abundantly clear, they’re billing the upcoming

June 23 event along Wilshire Boulevard’s “Miracle Mile” as “the most walkable CicLAvia ever!”

“This all feeds into the ultimate purpose of CicLAvia—to connect people with their community in a way that is not possible in a car,” said CicLAvia spokesman Robert Gard. “On bike and, more specifically, on foot, you are really able to interact with your fellow Angelenos.”

But turning that long-held aspiration into a reality has proven increasingly elusive as the event’s popularity has grown. The last event, which opened a 15-mile stretch of streets from downtown to Venice Beach, drew a crowd of about 180,000 people, according to Gard. The overwhelming majority of them were on bikes. “There are so many bicyclists now, walking appears to not be part of it,” Gard said.

Unlike the last route, however, the new one along Wilshire Boulevard will be just 6 miles, with pedestrian-only zones at each end. Although architecture tours and other walker-friendly activities are planned, organizers think the location itself may lure more walkers. The Wilshire route will offer more street life and more sights—from MacArthur Park to Koreatown to “Miracle Mile,” with its museums and vibrant arts scene.

Of course, any event with “cycle” in its name is bound to attract a bike-heavy crowd. But part of the challenge is simple growing pains, Gard said. CicLAvia was inspired by ciclovías in Bogotá, Colombia, which began in the mid-1970s. L.A.’s first event was held just three years ago, and local cyclists jumped at the chance to freely ride streets, where automobile traffic normally makes biking nerve-wracking, even perilous.

Once people realize CicLAvia events are here to stay, bike riders won’t jump at the chance to ride every one of them for fear they’re missing a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. “In talking with our peers in Central and South America, once they were more established, people understood it better,” Gard said. In time, serious bicyclists came to accept that ciclovías were for riders of all ability levels—and for pedestrians, too.

Alissa Walker, a member of Los Angeles Walks’ steering committee, said attitudes have already started to change.

“It has gotten a lot better,” Walker said. “At first, people didn’t understand that it wasn’t a race or something. It was possibly dangerous.”

CicLAvia organizers, in hoping to encourage that evolution, highlighted the problem using a video of a disabled man describing how he was verbally abused and directed off the streets because he was on a special, motorized device to accommodate his disability.

The City of Los Angeles’ first-ever pedestrian coordinator, Margot Ocañas, has participated in all six CicLAvias—sometimes on foot, sometimes on bike. She believes that continued, heavy interest from cyclists will mean that the roads “below the curb” will probably remain dominated by bikes, while pedestrians will take the sidewalks. For safety’s sake, she said, that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

Creating more pedestrian-only areas could help bring out more walkers, Ocañas said. She also envisions using the main route as a “launch pad for walking activities that tentacle off into other areas.”

No matter how CicLAvia evolves, everyone agrees that it should keep on rolling, stepping and hula-hooping.

“The fact that the bikes and pedestrians are having that conversation,” Ocañas said, “I’ll take it any day over bikers or pedestrians having that conversation with a car.”

There were so many cyclists at April's event that they became walkers, like on this stretch of Venice Boulevard.

Posted 6/6/13

Hot new workplace accessory: a bike

May 9, 2013

Bike to Work Day is Thursday, but cycling to work is increasingly common on any given day in Los Angeles.

Bike commuting appears to have turned a corner in Los Angeles, with new lanes and a burgeoning youth-oriented bicycle culture tempting more and more workers to saddle up.

“I think we have reached a tipping point,” said Lynne Goldsmith, manager of Metro’s bicycle program.

Next Thursday, May 16, is Bike to Work Day—one part of Bike Week, Metro’s annual celebration of pedal power. Metro and local advocates are expecting thousands of cyclists to participate. They hope some will shift their commuting habits for good.

Goldsmith said the number of trips taken by bicycle in the county, for commuting or otherwise, has doubled since 2010. She believes the change is partly due to economic necessity and partly because cycling has become trendy with the younger generation.

“We don’t think it’s going to go out of style,” Goldsmith said. “I think it’s here to stay.”

Josef Bray-Ali, owner of Flying Pigeon Bikes in Northeast L.A., seconded that notion.

“Fewer young people are getting driver’s licenses,” said Bray-Ali. “We have an economic crisis. A bunch of people may not be able to afford a car, but they can get a bike.”

Bray-Ali said “fixies”—single-gear bikes decked out with bright colors and other design details—have become wildly popular among the younger generation. “They buy fixies to knock around town with friends, but then they get jobs or go to college,” he said. The cycling habit follows them, and eventually they upgrade to higher-end bikes with commuter-friendly features like chain guards and rear-mounted racks.

UCLA’s experience supports this trend. Since 2005, the number of students and employees commuting to campus has tripled, said Dave Karwaski, associate director of transportation for the school. A desire for a healthy lifestyle combined with new infrastructure played a large part in that change, he said. UCLA is already a bronze-level “Bicycle Friendly University,” according to the League of American Bicyclists. Over the next few years, the university intends to make further improvements to get to a silver or even a gold rating.

Experienced bike commuters like Jeff Chapman echo the importance of infrastructure. For him, safety is paramount—he often tows his young children to school by bike. But, as director of the environmentally-conscious Audubon Center of Highland Park, he also appreciates the fact that pedal power is non-polluting.

He said his kids really enjoy the ride, too.

“They are learning directions better and we see cats along the way,” said Chapman. “They’re interacting with the community in a different way than they do in the back of a car.”

Another bike commuter, Cy Eaton, has cycled in lots of cities—New York, San Francisco, Portland, Chicago and Vancouver, to name a few. “In terms of that list, L.A. ranks toward the bottom,” he said. “But that’s a pretty stout list to compete against.” Since moving here, he’s had to upgrade to sturdier tires because flaws in the asphalt were giving him too many flats. He said the surface of most bike lanes in L.A. is “very disappointing.”

Still, Eaton notices a lot of improvement around town. Having previously lived in Los Angeles in 2008, he moved back last year. His current commute takes him 8 miles in each direction between East Hollywood and Burbank. He’s not riding in fear like he used to.

“I was pleasantly surprised with how aware motorists have become of cyclists,” said Eaton, adding that bikes on the road are no longer a “novel occurrence” in L.A.

For its part, Metro is using education to create a safer experience. The agency’s “every lane is a bike lane” campaign aims to inform drivers that bikes have the right to a full lane of roadway in some circumstances. In June, the target audience shifts to the cyclists. Joining forces with the L.A. County Bicycle Coalition and Bike San Gabriel Valley, Metro will use a federal grant to fund 90 three-hour safety lessons, through September. Participants will receive free helmets and bike lights as a bonus.

Metro’s Goldsmith said that, in the future, “the nut we have to crack is businesses. We need to convince businesses that they will grow if they encourage bicycling on their block.”

Just like in the streets, indoor infrastructure like bike lockers and showers is important to getting more people to cycle to work, said Linda Lyles, executive director of Century City Transportation Management Organization.

To draw more newbies out for Bike to Work Day, Metro is sponsoring bicycle pit stops with snacks, water, reflective decals and other giveaways. Those who sign a pledge to bike to work that day will be entered into a prize drawing, and all riders with a bike and a helmet will be able to board Metro and other regional transit providers for free.

Posted 5/9/12

Of broomsticks and bikes

April 23, 2013

Thanks to a multi-million dollar infusion from NBCUniversal, L.A. River cyclists have something to cheer about.

With a promise of transforming Los Angeles tourism, The Wizarding World of Harry Potter is coming to Universal Studios as part of the company’s $1.6 billion expansion of its theme park and backlot. But there’s another attraction coming, too—with a constituency as fanatical as any Hogwarts crowd.

In a deal pushed and brokered by Los Angeles County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, NBCUniversal has agreed to put $13.5 million into an effort to revitalize the Los Angeles River and complete a miles-long stretch of the river bikeway. And while the price-tag may seem small compared to the giant numbers behind the Potter venture and backlot expansion, it promises to be just as transformative in the worlds of alternative transportation and river restoration.

“It’s huge,” said Eric Bruins, planning and policy director for the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition. The development of the Los Angeles River and bikeway, he said, “creates a place where families can go and step away from the city while still being close to home.”

The recreational and commuting potential of the existing Los Angeles River Bikeway has been undermined by a nearly 6.5 mile gap between Griffith Park and Studio City. In negotiating a development agreement with NBCUniversal, Yaroslavsky pushed the company to focus its “community benefits” efforts on completing that vital stretch of the bikeway—despite the entertainment conglomerate’s earlier resistance to the idea.

“This project presented a singular opportunity to ultimately create a seamless bikeway from Long Beach to the San Fernando Valley,” Yaroslavsky said Tuesday prior to the board’s unanimous endorsement of the company’s “evolution plan.” “A big gap in this dream was the segment adjacent to NBCUniversal. Both the county and NBCUniversal seized the opportunity to solve this problem. Thanks to all involved, we can now look forward to planning and constructing the next generation of bikeway for our region.”

NBCUniversal has agreed to provide Los Angeles County with funding to fully complete an initial leg of the bikeway between Griffith Park and Lankershim and Barham boulevards, near the Universal Studios backlot. The remaining amount of the $13.5 million would then be used for the planning, regulatory and construction needs for the remaining stretch to Whitsett Avenue in Studio City. The company also has agreed to build a nearly 1-acre trailhead park along the river.

Among the groups who’ve long pushed for the expanded bikeway was Friends of the Los Angeles River. Its founder and president, Lewis MacAdams, applauded NBCUniversal’s “unprecedented generosity.” The cooperation between Universal and the environmental community, he said, “has set a very high bar for the rest of the media companies that line the banks of the river’s ‘Studio Stretch’ in the years to come.”

The Los Angeles River Revitalization Corp. also was instrumental in the public-private coalition that led to the unprecedented funding by the studio, which has been located along the concrete-sided waterway since Hollywood’s earliest days of filmmaking. The non-profit organization’s executive director, Omar Brownson, called the proposed bikeway extension the “cornerstone for the connectivity for all 51 miles of the L.A. River.”

But just as important, he said, the entertainment company’s involvement also sends a powerful message about “how we see and invest in our river. For a long time, it was looked at as a liability. Now people are looking at it as an asset.”

Posted 4/23/13

Here’s a car-free route to the beach

February 22, 2013

However you roll, you won’t want to miss the next CicLAvia, which blazes a new trail through the Westside before culminating at Venice Beach.

The map for the April CicLAvia was released this week, showcasing the event’s longest route so far, stretching about 15 ¼ miles between City Hall and Venice Beach. It follows Venice Boulevard most of the way, although there are shorter stretches on Figueroa, Main and 2nd streets downtown.

Since 2010, the popular bike and pedestrian events have reached out to new communities while opening up some of L.A.’s streets for healthy car-free fun. This is CicLAvia’s deepest foray yet into the Westside.

The moveable street party runs from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. on Sunday, April 21.

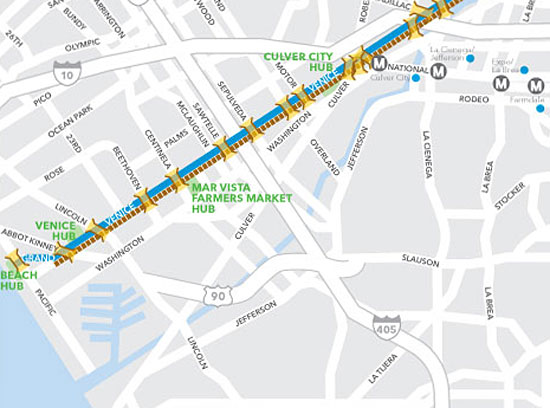

CicLAvia “hubs”—providing meet-up places and pit stops for refreshments, relaxation, and bike repairs—will be located at El Pueblo, City Hall, Normandie Avenue and along Venice Boulevard in the Fairfax District, Culver City, the Mar Vista Farmers’ Market, near Abbot Kinney and at the beach .

Posted 2/22/13

Westward ho for CicLAvia

January 17, 2013

Manifest destiny: CicLAvia's getting ready to roll all the way to the coast. Photo/planetc1 via Flickr

Saddle up, Westsiders: L.A.’s favorite rolling street party is headed your way in April.

CicLAvia, the car-free bicycle and pedestrian fest started in 2010, is on the move again, preparing for its most ambitious year yet with three events, including one that will stretch from downtown to Venice Beach on April 21.

It’s part of a major expansion that organizers hope eventually will stretch to all corners of the county and create 12 separate, localized CicLAvias each year.

“Up till now we’ve been downtown. Now we want to show that it will work in the rest of the region,” said Aaron Paley, CicLAvia’s co-founder. A second 2013 CicLAvia is being planned for June 23 with a new route expected to run along Wilshire Boulevard from downtown L.A. to Fairfax Avenue near LACMA. And this year’s third event, on October 6, will return to familiar territory downtown, although with a deeper stretch into Boyle Heights and a new route into Chinatown.

The downtown-to-Venice Beach route will be the longest yet for CicLAvia—15 ¼ miles each way—and carries with it some important cross-town symbolism.

“One of the things that’s exciting about connecting downtown and the Pacific is just the sheer drama and the significance of it,” Paley said. “We know that the east-west connection is very difficult and for people who drive it every day, it’s a challenge…The idea that you will be able to walk or ride your bike—or go in your wheelchair or do your inline skating—and go from downtown to the beach is just of historic significance.”

Venturing out on such a long ride should be attractive to many participants, but Paley said the event is more about creating a pop-up “linear park” on city streets than throwing down an endurance challenge.

“This isn’t the marathon. It isn’t all or nothing,” he said. “We want kids to be able to explore, maybe get out and ride in the streets for the first time that day. And if they ride a half mile, that’s great.”

The hope is that participants will arrive via public transportation if possible—perhaps by taking the Expo Line to the Culver City station at Venice and Robertson, or riding the bus to the Pico/Rimpau Transit Center at Venice and San Vicente.

Paley said the impetus for pushing outside the downtown zone and toward the ocean this year came from Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, who kept asking: “When can we go all the way to the beach?”

The mayor, he said, even burst into a planning meeting to promote the idea—prompting a round of brainstorming in which the Department of Transportation’s special events traffic guru, Aram Sahakian, came up with the idea of using Venice Boulevard, a route traveled by other events like the Los Angeles triathlon.

“We’ve used it before. We know exactly what we’re dealing with,” Sahakian said.

Taking the route deep into the Westside—where traffic woes are among the city’s worst—will require plenty of outreach to make sure residents and businesses know what’s coming. “I’m crossing my fingers and praying that they won’t be too unhappy,” Sahakian said.

So far, so good, said Diana Rodgers, who manages the Mar Vista Farmers’ Market and is enthusiastic about the coming of CicLAvia to her area.

“We love it and we want to be a partner and provide refreshments,” she said.

The farmers’ market, which takes place on Sundays and is located on Venice at Grand View Boulevard, is accustomed to rolling with the closures that come with big events like the marathon and triathlon, Rodgers said, and should be able to take CicLAvia in stride.

“As long as we have the information, we tend to do OK, as long as we have crossing guards at the points needed,” Rodgers said.

Westside cyclists like Cynthia Rose, director of the group Santa Monica Spoke, said the new route will be a big draw in her part of town.

“There’s a huge pool of enthusiastic Westside supporters and they’ve felt sort of geographically separated,” she said. “Now all of a sudden it’s going to be that connecting of the dots, from the ocean to downtown Los Angeles.”

Paley said the final map for the downtown-to-Venice Beach route is still being fine-tuned. The CicLAvia team will be taking an exploratory ride along the proposed route Sunday to see how it works and connects with two major hubs downtown—City Hall and Union Station.

Beyond the 2013 lineup, he’s looking forward to CicLAvia’s gradual multi-year expansion.

“We want the entire county to be able to benefit from Ciclavia,” Paley said.

So what’s on tap for 2014? “I can tell you that the Valley,” Paley said, “is high on our list.”

Posted 1/17/13

A giant step for L.A.

November 18, 2012

Margot Ocañas, the city’s new pedestrian coordinator, at the intersection of Wilshire and Fairfax this week.

In some ways, Margot Ocañas has been walking the walk ever since she was a kid growing up in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and her mom sent her off to modern dance lessons with the words:

“You’ve got two feet and a bicycle. Get going.”

Talk about prophetic. Today, Ocañas—a Mandarin-speaking Fulbright scholar and one-time Wall Street analyst whose resume also includes running an independent film company with her husband and developing “streets for people” projects at the county Department of Public Health—is jumping feet first into a brand new role with major ramifications for how L.A. moves into the future.

As Los Angeles’ first pedestrian coordinator, Ocañas, 48, is front-and-center of a growing movement that aims to rethink streets as we know them.

Her appointment is just the latest sign—along with car-free CicLAvia events, a new pedestrian plaza in Silver Lake and a burgeoning public transit system—of how Los Angeles is throwing off its car-centric reputation in sometimes unexpected ways.

“The national momentum is very much our friend right now,” Ocañas said. Pedestrian awareness is “part of a larger national conversation. People are in tune with that.”

Ocañas and assistant pedestrian coordinator Valerie Watson, an urban and regional planner by training, have recently joined the city Department of Transportation. Their mission: making life better for walkers on streets that often were built mostly to enable automobiles to get from Point A to Point B as efficiently as possible. The tools of transformation include reshaping lanes and crosswalks, changing signs and signals—anything to foster calmer corridors and reduce the “raceway mentality” that’s rampant on many streets.

And then there are those things that are beyond the DOT’s purview—such as “street furniture” like benches and light fixtures. “To enhance the safety and the warmness of a corridor, you might want to start installing more of what I call human scale lighting. You may have flower baskets, or trash cans,” she said. “I think it’s those types of amenities that just make it feel more like an outdoor living room.”

Since sidewalks and street furniture fall under the Bureau of Street Services, not the DOT, part of her job involves reaching across departmental lines. “There are just increasingly strong strategic working relationships and partnering that’s happening with Street Services and Street Lighting,” she said.

Deborah Murphy, founder of the pedestrian advocacy group Los Angeles Walks and chair of the city’s Pedestrian Advisory Committee, said she’s been urging the appointment of an L.A. pedestrian coordinator for more than 15 years. While Los Angeles still has a long way to go to before it catches up with other cities including, locally, Santa Monica, she senses a permanent transformation is underway.

“I have really seen a huge change in the last year,” she said. “I’m thrilled. I think Margot and Valerie bring lots of great energy to pedestrian safety, and to encouraging people to walk.”

The well-traveled Ocañas, who moved to Los Angeles in 2003 from New York by way of Austin, also thinks the moment is right for the city to get in touch with its pedestrian side. She’s reached out to counterparts who are on the same journey in New York, which is regarded as a national leader in reconfiguring streets, notably in Times Square, as well as in San Francisco and Chicago. She thinks it can’t hurt that stratospheric gas prices are making alternative modes of getting around look better and better these days.

“Selfishly, I’d love to see gas prices not go down,” said Ocañas, who gets to work by bike, bus and foot three days a week and has organized a “bike train” caravan to get her two children to school each morning. “I could be talking till I’m blue in the face but there are certain triggers that just force behavioral change.”

Walk a mile in her slingbacks, and you’ll quickly get a sidewalk-level view of what’s good, bad and ugly out there on the L.A. pavement.

At the busy triangular intersection where Fairfax, Olympic and San Vicente come together, Ocañas watched one morning this week as pedestrians scrambled to cross. She reflected on how broad streets with short signal times can pose difficulties, especially for the elderly.

“I have seen situations where seniors are caught three-quarters of the way across the street and the light has turned,” said Ocañas, who lives in the neighborhood with her family. “We do have a population that’s getting older. We need to adjust signaling to ensure their ability to cross more effectively.”

Beyond that, “unwelcoming” streetscapes can send a forbidding signal to just about anyone who’s not in a car.

“People are not incented, or motivated, or enthused at times to get out and walk,” she said. “But those times are changing.”

Her proposed solution: “Re-engineer the environment.”

Ocañas’ previous position as a policy analyst at the county Public Health department’s Project RENEW, funded with federal stimulus dollars, involved working on grant proposals intended to combat obesity by confronting challenges in L.A.’s “built environment”—such as those long, unshaded stretches of roadway where fast car traffic and widely separated crosswalks make it uninviting or impossible for pedestrians to stroll and interact.

“When I was on the health side, we always talked about, ‘We’ve built ourselves into sickness so we need to build ourselves out of sickness,’ ” Ocañas said. One of the projects she worked on turned into the green polka-dotted Sunset Plaza Triangle pedestrian zone in Silver Lake, which opened in May.

Her own transformation, from a career in the private sector that included working at Dell Computers, started modestly enough, with a block party closure she organized to give neighborhood kids a chance to wheel around freely on their bikes and scooters. Ryan Snyder of the urbanist transportation planning firm Ryan Snyder Associates was there as the guest of a neighbor. When he met Ocañas, he mentioned the upcoming policy analyst positions in Public Health.

A light bulb went on. “It never occurred to me to consider taking a recreational passion and translate it into a paying job,” she said.

At the city Department of Transportation, Ocanas’ and Watson’s first priority is developing a Safe Routes to School Strategic Plan for the city. The “data-driven” plan will help the department prioritize spending on student safety projects and will introduce “new types of pedestrian-centered amenities” into the mix. It also will serve as a building block for the eventual creation of a “Pedestrian Safety Action Plan” for Los Angeles—something that’s probably three to five years down the road.

At the same time, they’re working to foster innovative “place making,” including “parklets” (tiny curbside areas the size of parking space, often in front of businesses and furnished with seating areas and plants) as well as bike corrals and pedestrian plazas like the one in Silver Lake.

“You do these things that you can quickly implement with low-cost materials…to help demonstrate the benefits of ‘people-space,’ ” Watson said.

Ocañas, who like Watson is being paid by DOT Measure R funds that have been targeted for pedestrian initiatives, said she’s finding the department a “very supportive environment.”

“I actually find them very open,” she said. “We will debate. I will learn from them: ‘OK, you just can’t do that, and for these reasons.’ But similarly, they are very open to ‘Why not?’ ”

Posted 10/18/12

CicLAvia heads down a new road

October 3, 2012

The Bicycle District is usually packed for CicLAvia but now the event is rolling out to new communities.

For the first time since its inception, the freewheeling car-free street party known as CicLAvia won’t be cycling through Los Angeles’ Bicycle District when it rolls around this Sunday.

The Heliotrope and Melrose neighborhood known for its pioneering, bike-friendly ethos and jaunty nickname “Hel-Mel” has been penciled out, this time around, in favor of a map that stretches farther south than ever before—from downtown to Exposition Park and USC. It also includes a new northerly hub in Chinatown, an eastward stretch to the Soto Gold Line station in Boyle Heights, and a stop at downtown’s new Grand Park.

As CicLAvia prepares for its fifth outing, its new map is just the most visible sign of an enterprise that’s literally on the move, stretching into new areas easily reached by L.A.’s growing public transit network. Pedestrians are taking their biggest step yet toward claiming their place on the pavement, as Los Angeles Walks sponsors a mid-day “walking parade” dubbed WalkLAvia down the middle of Figueroa from 8th Street to Exposition Park. And, with ambitious plans to expand and integrate CicLAvia more deeply into the fabric of the city, efforts are underway to significantly increase the amount of corporate support to sustain the event in years to come.

The course is actually slightly shorter this time—9.1 miles, compared to the previous 10. But clearly, CicLAvia’s cultural footprint is big, and growing, with more than 100,000 participants expected Sunday for the event, which runs from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m.

“We instantly, overnight, became the largest car-free event in the United States,” said Aaron Paley, who helped found CicLAvia and now serves as its executive producer. “We went from being an idea…to becoming something that Angelenos expect out of their city. A car-free day is now just as much a part of Los Angeles as the Venice boardwalk, or the Hollywood sign. We changed the conversation in Los Angeles.”

It was never (entirely) about the bike, Paley said, noting that three distinct groups—cyclists, environmentalists and public space planners—came together to create the original CicLAvia in 2010. They’re now being joined by many others, including health activists, as the event enters the L.A. mainstream.

“CicLAvia itself is much larger than a biking event,” Paley said.

The new route, thanks to its proximity to the recently-opened Expo Line, makes it easier for many communities to take part, said Tafarai Bayne, community affairs manager of the neighborhood action group T.R.U.S.T. South L.A. and a CicLAvia board member.

“We definitely think we’ll increase turnout from neighborhoods like South L.A. and the Westside,” Bayne said, noting a “huge surge” in youth cycling that provides a natural constituency for the event. The setting makes sense, too, he said: “We have really big, wide boulevards that this event can take advantage of.”

In the Bicycle District, a popular café, Cafecito Organico, is having to adjust to the idea that CicLAvia will be passing it by this time around. “It is quite a disappointment,” said Angel Orozco, one of the partners in the business. “CicLAvia is our busiest day of the year.”

But at Orange 20 Bikes, another neighborhood fixture, customers seem to be taking the new route in stride as a necessary step in drawing new participants to CicLAvia. Most are eager to see their collective “passion and excitement” for the event shared with “underserved communities” around Los Angeles, said Nona Varnado, Orange 20’s outreach coordinator.

And if CicLAvia won’t come to the Bicycle District, the Bicycle District will come to CicLAvia—in the form of an Orange 20 team that will be setting up shop Sunday at the Mariachi Plaza hub in Boyle Heights, offering free bicycle maintenance and community education.

“Wherever CicLAvia is, we’ll be there,” Varnado said.

To borrow some familiar buzzwords from the presidential race, it’s as if regular cyclists are “the base,” and everyone else is a “swing voter.” And turnout, naturally, is the name of the game.

“Everyone I know in the bike world comes out,” said Bobby Gadda, president of the CicLAvia board. “It’s like a convention of bicyclists. Now it’s going beyond that. There’s all kinds of people mixed in. That’s what’s so great about it.”

A particular effort is afoot to boost pedestrian participation. It’s no accident that the official press release describes CicLAvia as a “car-free, linear park for strolling, biking, playing, and experiencing the city from a new perspective.”

The 3-mile WalkLAvia parade down Figueroa (“Strollers welcome”) aims to send a festive but clear signal that pedestrians have just as much right as bicyclists to enjoy the car-free streets.

During the previous CicLAvia, “we found some bicyclists a little on the aggressive side,” said Jessica Meaney, an L.A. Walks volunteer and the Southern California coordinator for the Safe Routes to School National Partnership.

The new route down Figueroa is big and open, and the hope is that bicyclists will notice the parading pedestrians and “share the space,” Meaney said. “We consider ourselves traffic calmers.”

CicLAvia is free to participants but it’s not free to put on. The city of Los Angeles shares the cost with the CicLAvia nonprofit organization, which raises money from foundations, government grants, individual donations (including proceeds from the sale of raffle tickets and merchandise) and from corporations.

Current corporate support comes from firms such as REI, Small Planet Foods and Larabar.

“Corporate support, we hope, will grow over the next two years. It’s been small so far,” executive producer Paley said. “We hope to actually change that so corporations become 20 to 25%” of CicLAvia’s fundraising.

“We are definitely looking at a whole range of things,” he added. “It’s all about making it sustainable.”

Posted 10/3/12

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink