Community Law Enforcement

Jail alternatives gain momentum

July 31, 2014

Thousands of mentally ill inmates are in L.A. County jail cells, making succesful treatment unlikely.

In recent months, a single word has dominated Los Angeles’ criminal justice debate, one that’s positioned the county’s top prosecutor as a champion of reform and consumed meetings of the Board of Supervisors, including this week. The word: diversion.

District Atty. Jackie Lacey, in her first term, is at the forefront of a growing, multi-jurisdictional initiative to provide community-based diversion to thousands of county inmates who suffer from mental illness and can’t be effectively treated behind bars. This, she argues, creates a cycle of recidivism that’s harmful to the individual and that ripples through society. Lacey is expected to present her recommendations in September to the supervisors, who’ve also been confronting the diversion issue.

In early June, the U.S. Department of Justice, noting a rise in jail suicides, criticized the county’s handling of mentally ill inmates and said it was prepared to seek federal court oversight of the lock-up, which is operated by the Sheriff’s Department. But the agency made a point of praising the county for its recent efforts to explore diversion for low-risk offenders.

Diversion also played a key role in the board’s recent debate to raze the old Men’s Central Jail and build a new one designed to double as a treatment facility for inmates with mental health needs. At a cost of at least $2 billion, Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky cast the only dissenting vote, arguing that community-based diversion programs should have been fully explored before the county committed to its most expensive construction project ever.

On Tuesday, the board again tackled the topic—this time debating a motion by Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas to, among other things, commit $20 million for a “coordinated and comprehensive” diversion program for mentally ill inmates. The board, he argued in his motion, “needs to demonstrate its financial commitment to diversion.”

Although supervisors expressed strong support for placing low-risk mentally ill inmates in community-based diversion programs, the majority 0pposed earmarking money without a spending plan. The better way, they said, was to see what Lacey recommends and then consider the funding during the board’s late September budget process.

“We would be making a huge mistake just throwing money at it and saying: ‘Look at us. Aren’t we great at diversion?’” said Supervisor Gloria Molina. “We need to be thoughtful. We need to have a plan.”

Supervisor Yaroslavsky said that nearly a decade ago, the county set aside tens of millions of dollars to combat homelessness. But like now, he said, there was no blueprint for spending it. “We were so excited to have the money to set aside,” he said, “we forgot to develop a plan. And so we shouldn’t make that mistake a second time.”

“We need to have a road map,” Yaroslavsky continued. “I have confidence that under the leadership of the district attorney, with the participation of all of us, we can develop something like that.”

The board voted to consider the motion’s funding element during supplemental budget deliberations in late September.

Posted 7/31/14

Elementary, my dear camper

July 10, 2014

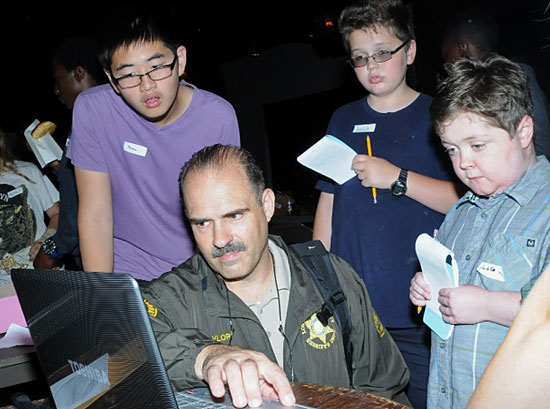

Sheriff's Det. Greg Taylor goes over a mock surveillance video with a group of young campers in June.

It’s been a while since his dad noticed the ad for the summer camp in the local Agoura Hills newspaper. Still, the experience made an impression on Max Bartolomea, now 17.

“It was a murder in a hotel room,” the Oak Park high school senior recalls, chuckling. “The body was gone but the room was still bloody. I loved it—I remember thinking it was exactly how it looked on TV.”

Now in its fifth year, the Los Angeles County Sheriff Department’s Teen C.S.I. Camp, complete with mock crime scenes, has evolved and expanded, but its impact on kids remains.

“It’s fun and they learn a lot,” says Deputy Scott Rule, who devised the camp curriculum in 2009 at the behest of Agoura Hills city officials. Then a member of the Juvenile Intervention Team at the Malibu/Lost Hills Sheriff’s Station, Rule has since taken the show to the sheriff’s Altadena station, where he’s now posted.

“It’s like getting to solve a mystery.”

Los Angeles County has summer diversions aplenty, from art camps at LACMA to nature adventures at the Natural History Museum.

But the sheriff’s Teen C.S.I. Camp has been a sleeper, locally available until now only through the City of Agoura Hills, where municipal officials inspired by crime scene investigation TV shows first floated the idea to the sheriff’s department.

“I actually had one of my own kids go the first year,” recalls Sheriff’s Lt. Jim Royal. “They did a mock murder. There was a preliminary lecture on technique, and then they did forensics—we had our print person come out, and the kids got to take notes and try to figure out who did it. After that first session, it was standing room only. It was a really great idea.”

Since then, sheriff’s officials say, the 5-day camp has steadily added features, though it always revolves around a single “crime.”

“That first year, we did a homicide in a party setting,” recalls Rule. “We used a mannequin for a victim and set it up in a room at a park that the city rented for parties. The murder weapon was an alcohol bottle.

“But we’ve done all sorts of things—one year we had a shooting victim, another year we had a stabbing. Once I even had a bar fight with a pool cue as a weapon. This summer in Altadena, it was a baseball bat.”

Each crime scene, he says, is carefully seeded with clues, from fingerprints to footprints to footage from security cameras. Then the campers, who range in age from 11 to 16, try to deduce whodunnit.

“We don’t make it graphic,” adds Rule, noting that the “victims” are rarely female and never children.

“We want it to be easy and solvable, not gory and bloody. We use plastic knives and the one year we did a gunshot victim, we used a plastic training gun. But every one of those cases are like scenes our detectives have been on—murder scenes, assault scenes, thefts, burglaries.”

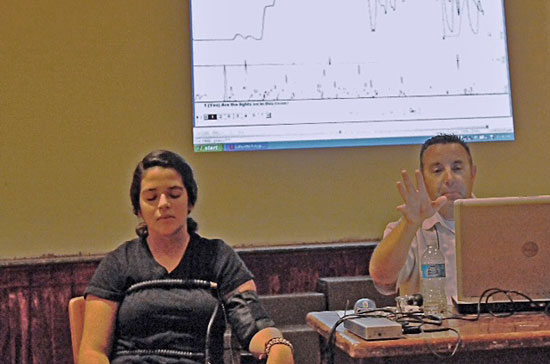

The aim, he says, is to put forth a positive image for the department and to engage adolescents with technology that intrigues them (polygraphs, he says, are a guaranteed crowd pleaser.)

But, he adds, the camp also introduces teens to the range of potential careers in law enforcement, from crime lab work to prosecutions.

“I always try to find a local attorney to come out and play the District Attorney, so the kids can present their case and see what kind of charges they can get.”

This is the first year the camp has been offered at the Altadena station, Rule says. A $75 June session drew 23 youngsters—enough to prompt the addition of a second session from August 4-8. (For more information, click here.)

Meanwhile, in Malibu, sheriff’s officials say they had to tweak the curriculum slightly because the local forensic specialists who usually help guide campers were so occupied with real crime that they couldn’t participate without an overtime budget.

Instead of a C.S.I. Camp, the sheriff’s offering will be called “Secret Agent Camp” this year. The camp will run from August 11-14, and will be available through the City of Agoura Hills for $74. (Details are here.)

“We have our own fingerprint [technician] who works here already, and I supervised the crime lab for years, so we will still have a forensic element—it just won’t be as technical,” says Malibu/Lost Hills Lt. David Thompson.

Deputy Alicia Kohno, who has succeeded Rule, promises that the camp will still include all the usual, popular features—a murder, a crime scene, fingerprints, footprints, lie detectors.

Good, says Bartolomea.

Though the teen never aspired to a career in law enforcement—according to his mother, he’s headed later this summer to a USC program for potential medical students—one of his favorite things about the camp was its taste of serious police work.

“I remember thinking that it was really cool,” he says. “And really real.”

Posted 7/10/14

Searching a web of clues

May 30, 2014

Scouring social media sites, sheriff's researchers have put a serious crimp in hundreds of teen parties.

There are no bigger party poopers in town than a tiny team of web savvy sleuths in the Sheriff’s Department, who patrol social media looking for potential trouble, including jammed-to-the-rafters raves that promise alcohol and drugs to underage partyers, particularly teenage girls.

During the past few years, the little-known unit has “intercepted” and helped block 1,000 parties before they even got started, according Cmdr. Mike Parker, the department’s leading authority on social media and online communications.

Sometimes, Parker said, deputies are dispatched directly to doorsteps, where they warn adults that they’ll be arrested for contributing to the delinquency of a minor should the party go off as advertised on Facebook, Twitter or other social media sites. Other times, the deputies will join an online conversation among would-be celebrants with this buzz-killing greeting: “Thanks for the invite. See you there!”

As a result, the department’s proactive Internet strategy has short-circuited the assaults and neighborhood disruptions that often accompany raves—and saved public dollars that otherwise would be spent on patrols and prosecutors.

“If it’s being shared for all the world to see,” Parker said of the party promotions and other postings that raise red flags about public safety, “then it’s the social equivalent of standing outside of school with a bullhorn. There’s no expectation of privacy. But if, as a law enforcement officer, you’re pretending to be someone else, that’s where you get into that danger zone of Big Brother accusations.”

The notion of proactively scouring the web for possible crime clues has emerged on the public radar in a very different context in recent days. In the aftermath of last Friday night’s Isla Vista murders, sheriff’s officials in Santa Barbara have been questioned about whether they should have known more about the killer with whom they’d had earlier contact and who had posted provocative videos and rants. Authorities there have acknowledged that, while they were aware of Elliot Rodgers’ videos, they did not view them.

In reality, most local police agencies have yet to explore the potential of the Internet as a preemptive crime-fighting tool, one that requires training and staffing, just like any other specialized law enforcement job, says Parker, who emphasizes that he is not second-guessing Santa Barbara police.

“It’s not like a 911 call that you’re obligated to respond to,” Parker said the other day, as he prepared to deliver a social media presentation at the county’s annual leadership conference. “It’s a very different challenge. You have to go out and hunt, and you have to want to do it. You have to pride yourself on finding things.”

Parker, a 29-year-veteran of the department, is a nationally-recognized leader of that effort. Until his recent promotion as commander of the north county patrol division, he headed the Sheriff’s Headquarters Bureau, which included the new Electronic Communications Triage Unit. Today, he’s its consultant and evangelist.

The unit has two full-time members and some part-timers whose web work extends far beyond raves. Using “keyword” and “geo-tag” searches, they target issues that could touch a broad swath of society or a single family—from preparing for a flash mob that’s been promoted online to trying to rescue a suicidal teenager. Parker shared this story:

After an assault with a deadly weapon occurred in a particular neighborhood, one of the unit’s members began searching the web for postings by witnesses that deputies could interview. In the process, she discovered a posting by a neighborhood girl who was threatening to take her own life. She’d posted pictures on Instagram and revealed she’d been cutting herself.

A street sign in the background of one of the photos allowed deputies to zero in a possible home. On the first visit, no one answered. The second time, mother and daughter were both there, Parker said.

“That’s when the mom found out that her girl was cutting herself and wanted to kill herself,” he said, adding that the mother knew her teen was depressed but did not understand the depth of her despair. The girl was voluntarily admitted for mental health care.

Asked whether the deputies’ intrusion into the girl’s life could be seen as a breach of her privacy rights, Parker responded:

“A key element is that she is sharing what she is doing for the entire world to see, including a potential predator, who would see her vulnerability as something to exploit. Psychologists would call her actions an open cry for help. We heard her cries and came to help. Too often, people are afraid to get involved…and sadness and regret often follow.”

“We could probably keep someone busy fulltime just working on people who want to hurt themselves,” Parker said.

Looking to an increasingly digital future, Parker said he believes that a robustly staffed regional center should be created to help law enforcement officers scour the web for open source material that could produce investigative leads at any time of day, just like other kinds of multijurisdictional task forces.

“As I say that, I know civil libertarians get concerned,” he admitted. But he argued that people put information into the public domain for the world to see—“and I’m a member of the world.”

Cmdr. Mike Parker has been leading the way in using the Internet to proactively identfy potential trouble.

Posted 5/30/14

Board clears way for $2B jail

May 8, 2014

The grim Men's Central Jail will be razed for one that focuses on the needs of mentally ill inmates.

On the outskirts of a gentrifying downtown Los Angeles, where trendy eateries and pricey lofts are drawing a wave of hip urban pioneers, there sits a residence of a vastly different sort–“an antiquated, dungeon-like facility,” home to some 5,000 people, many of them mentally ill.

That’s how a blue-ribbon citizen’s commission in 2012 described the county’s notorious Men’s Central Jail, which has been around since the Kennedy Administration. More recently, the so-called MCJ was ground zero in the Sheriff’s Department brutality scandal that led to the indictments of 20 deputies and the departure of Sheriff Lee Baca.

For a decade, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors has been debating various plans to replace the old lockup with one that reflects the latest thinking in modern jail construction and management. Each time, the price climbed. The stakes were rising, too, as the federal government intensified its oversight of how the county was providing constitutional care for thousands of inmates with mental health problems.

So on Tuesday, under increasing pressure to act, a divided board set in motion what promises to be the most expensive construction project in the county’s history. It approved a nearly $2 billion plan to replace Men’s Central Jail with a facility designed to confront the unique architectural and staffing requirements for treating mentally ill inmates in county custody.

The board majority, which also voted to move forward the renovation of Mira Loma Detention Center in Lancaster to house women, picked one of five options for the new downtown jail provided by Vanir Construction Management, which was hired as a consultant by the supervisors. The company will not be a bidder on the project.

While there was no disagreement among board members about the need to replace the Men’s Central Jail, the potential price of the undertaking drew strong warnings from Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky. He cast the lone vote against authorizing the expenditure of $30 million to begin design work and an environmental review of Vanir’s “Option 1B.” (Voting in favor of the plan were Supervisors Don Knabe, Gloria Molina, and Michael D. Antonovich. Mark Ridley-Thomas abstained.)

Yaroslavsky argued that the board should have been given alternatives to incarceration that might reduce the number of mentally ill inmates in the new jail, thus possibly lowering the construction and operating costs borne by taxpayers.

“I think I have been, as a member of this board, somewhat shortchanged by not having that information available to me as I’m being asked to make a decision—a $2 billion decision,” Yaroslavsky said, adding: “All of us have been around long enough to know that if you’re telling us it’s $2 billion today, it’s not going to go down. It’s only going to go up.”

Yaroslavsky urged the board to delay a vote until more information on diversion programs for the mentally ill was provided, rather than being forced to decide solely on a series of construction scenarios. He also noted that District Atty. Jackie Lacey was leading a high-powered task force on mental health and substance abuse diversion that could inform the board’s ultimate decision.

Testifying before the board, Lacey said that since a big chunk of the new jail’s cost is for the mentally ill, “you should know that there’s a committed group of professionals …who are looking for alternative ways to address this issue. We’re serious about it, and I’m optimistic.”

Assistant Sheriff Terri McDonald, who oversees custody operations, acknowledged the importance of increasing capacity for inmates placed in community diversion programs. “I don’t think the right solution is just build, build, build, build. It’s too expensive. It’s not sustainable.”

But, she said, such efforts must “run along parallel tracks” with the design and construction of a new jail, which is essential for the inmates and the county’s legal position with the federal government.

Supervisor Antonovich, who, with Molina, pushed the vote forward, agreed: “If we don’t act,” he said, “the choice will not be ours, but up to a receiver who will force us to act, at a much higher cost.”

Posted 5/8/14

New sheriff writes a new chapter

April 17, 2014

When former Sheriff Lee Baca announced his surprise resignation to a crush of reporters in January, he closed with a heartfelt recitation of the agency’s “core values.”

“As a leader of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department,” he said, his voice wavering with emotion, “I commit myself to perform my duties with respect for the dignity of all people, integrity to do right and fight wrongs, wisdom to apply common sense and fairness in all I do, and courage to stand against racism, sexism, anti-Semitism, homophobia, and bigotry in all its forms.”

It was not the first time the sheriff had publicly, solemnly recited the code. He’d long ago committed the words to memory and had spoken them often during the ups and downs of his tenure—especially during those final months when he and his department were under siege for alleged deputy brutality in the jails.

But now Baca is gone. And so, too, is his code of core values.

On Monday, interim Sheriff John Scott sent out an all-hands email announcing the creation of a new statement, one containing “the same deeply-held values” but expressed in a new way. Scott explained that he’d reached out to a committee of deputies, sergeants and professional staffers to craft the new statement, with its extra emphasis on professionalism, compassion and accountability—words that were absent in Baca’s code.

“I will hold myself accountable for serving our Department and the public in a manner consistent with these values, and I will, in the same way, hold each of you accountable for your actions,” Scott pledged in his department-wide email.

What went unsaid was the subtext. Many in the rank-and-file had come to view the old code as a collection of empty vows, violated by some at the top of the organization, Scott explained in an interview.

The old code had become an example of, “do as I say, not as I do,” Scott said. “That was the driving force [behind the change]. The code should not be just nice words on a wall. It should reflect values you live by in the light of day and in the shadows of darkness.”

The new code was built around six words (one for each point of the badge) that the 12-member committee concluded best described how department members should conduct themselves in the pursuit of their mission, Scott said. Those words were then woven into this short statement:

“With integrity, compassion, and courage, we serve our communities—protecting life and property, being diligent and professional in our acts and deeds, holding ourselves and each other accountable for our actions at all times, while respecting the dignity and rights of all [emphasis included].”

Beyond its statement of guiding principles, the new code also is meant to send a broader symbolic message.

Since his temporary appointment by the Board of Supervisors in late January, Scott has wasted no time dismantling remnants of the Baca Administration that he believes had damaged morale, undermined the department’s effectiveness and broken the public’s trust.

Among other things, he’s shaken up the management ranks, created new internal controls and even banned cigar smoking on a patio at the agency’s Monterey Park headquarters that was frequented by friends of the top brass and had come to represent clubbiness and exclusion.

These actions, like the rewritten statement of core values, will let the troops and the communities they serve know that “this is a new beginning,” said Scott.

Scott has said he wanted to institute these kinds of changes nine years ago, while serving in the department’s command staff. But unable to get Baca’s buy-in, Scott said, he retired in 2005, later becoming the No. 2 official in the Orange County Sheriff’s Department, where he has led reform efforts in that once-troubled agency.

As part of Scott’s deal with the Board of Supervisors, he’ll return to Orange County after voters here elect a new sheriff either in the June primary or a November runoff. The board did not want an interim sheriff to be distracted by a divisive political campaign at a time when the department needed clear, focused direction.

The day after his appointment, Scott said, he shared a private meal with Baca to talk about the future of a department to which both had devoted decades of their lives.

“I told him, ‘There’s going to be some things I do and it’s going to be sensitive to you. It’s not personal. It’s not about me, it’s not about you. It’s about the department.’ ”

Posted 4/17/14

The dogs of war come home

August 8, 2013

She was a hero overseas and now Tula, along with handler Dep. Guillermo Loza, is making L.A. County safer.

Just last year, Tula was in Afghanistan, sniffing out buried explosives and saving lives and limbs in the war zone. Now her beat is Los Angeles County, where on a recent afternoon she put her exceptional sniffing abilities to work on a random stroller she encountered in Grand Park.

The glossy black Labrador retriever has traded in her military handler for a new partner on the homefront, Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Deputy Guillermo Loza.

Tula and Loza are part of Countywide Services Division K9, a new sheriff’s unit that started operating last month with a mission of keeping watch over county facilities, parks and events. Tula is an explosives dog, trained to find the various bomb materials that could be used in an attack. She and another black Lab, Ruby, joined the department after serving with the U.S. Marines in Afghanistan. There, Tula and Ruby were experts in locating roadside bombs known as IEDs, or improvised explosive devices. IEDs are the leading cause of fatalities for the U.S. and its allies, responsible for the deaths of 3,275 soldiers in Afghanistan and Iraq as of Memorial Day, 2013.

“They uncovered more than 40 IEDs each,” said Sergeant Mark Jennings, who heads the new division, which also includes his narcotics-sniffing dog, Chip. “They can’t give me a number of lives these dogs saved, but with convoys, it’s in the hundreds.”

Jennings, a former Marine, scored the sought-after hero dogs for Los Angeles County last fall in North Carolina, where representatives from dozens of law enforcement agencies vied for 50 of the returning military canines. The program is part of a campaign to place the dogs as the U.S. reduces its canine military strength in Iraq and Afghanistan from 480 dogs to 180.

As Tula and Ruby went through their paces in front of the law enforcement crowd, Jennings was impressed—and he wasn’t alone.

“Just about everyone wanted Tula and the other half wanted Ruby,” he said. “We had to do a drawing, and we got lucky.”

The 3-year-old Tula and the muscular 6’4” Loza made a striking duo as they made the rounds in Grand Park recently.

“I like your dog,” shouted a young girl while skipping toward the park’s splash fountain.

“Aww, what’s her name?” asked a woman dressed in business attire, while a tourist snapped a photo.

They’re getting used to attention from the public.

“At first they see this tall deputy and they’re like ‘oh my God’ but then they relax and say, ‘Oh look, there’s a dog here,’ ” Loza said.

On cue, Tula darted off and investigated bushes, trash cans, bags and anywhere else a bomb might be hidden. Finding nothing, she returned for a bit of affection and a chance to play with her favorite chew toy.

Like other veterans, Tula and Ruby returned with a few psychological scars.

“Initially they wanted to be very close to you,” Jennings said. “As far as noises and being around people, they were a little hesitant, a little jumpy. They definitely showed signs of what I call PTSD in dogs.”

Handlers of explosive-sniffing dogs need to be the best of the best too, Jennings said. The wrong handler “can screw up a dog very easily.” Loza and Deputy Danny Cassese, who handles Ruby, were at the top of their training class—a prestigious distinction.

Before being deployed, the dogs and deputies trained together with a local expert for four weeks. As they make the transition from military to civilian duty, it helps that they are Labradors, a popular pet breed. The dogs are mellow and gregarious in crowds. German shepherds, on the other hand, tend to intimidate people, Cassese said.

The biggest hurdle was training Tula and Ruby to work on leashes. In Afghanistan, all their searching was performed “off-leash.” Handlers would send them ahead to scout for explosives. On their new beat, much work must be done “on-leash.”

Yet the ability to work off-leash is what sets Tula and Ruby apart from the dogs assigned to the 60 other K9 units in the county, which search for bombs and also things like narcotics, guns and dead bodies. Working off-leash allows the former war dogs to explore suspicious situations while human deputies keep a safe distance.

The dogs live with the deputies and the pairs develop a close bond, which is essential to their performance. Continued training is part of the job description and up to 3 hours of each shift is devoted to it. When the day is done, Tula and Ruby live the good life of any other well-cared-for pet in Southern California. Tula likes running on the beach and investigating every corner of Loza’s house, while the 5-year-old Ruby “will play with a tennis ball until she passes out,” Cassese said.

The deputies receive daily training on trends in terrorism and counter-terrorism efforts, said Loza, who believes domestic attacks like the Boston Marathon bombing could increase as U.S. war efforts draw to a close and create a greater focus on stateside targets. That’s where Tula and Ruby come in.

Last week, the dogs “cleared” (declared safe) a suspicious package at Los Angeles City College. Their biggest find so far came on a parole compliance sweep, which is one of their secondary duties, performed on request. Because guns and ammunition contain gunpowder, the dogs can detect it. Ruby located a belt of 75 high-caliber rifle rounds meant for a machine gun, 50 smaller rifle rounds and a 12-gauge shotgun round that were in the possession of a prior felon. (Loza said both dogs found the bullets, but Ruby got the credit “this time.”)

Jennings said the program is a great financial deal for the county. Bomb-sniffing dogs are bred specifically for the task and undergo months of expert training. All told, each would normally cost upwards of $50,000. As more return from the war, Jennings hopes to expand the division to include up to 5 more K9 teams.

Not all returning war dogs are deemed young enough and fit enough for further service. Some have had serious injuries.

Bob Agnor, a senior trainer for K2 Solutions, a company that provides the dogs and training to the military, said those dogs are returned to civilian life, often being adopted by their Marine handlers.

“These dogs literally saved their lives,” said Agnor, whose company hosted the North Carolina event at which Tula and Ruby were recruited. “They think, ‘This dog has earned the right to live in my house and be treated like a king or a queen.’ ”

Tula and Ruby still wear military dog tags in honor of their service abroad. When they retire from the Sheriff’s Department, Loza and Cassese will have the first option to adopt.

“I’ll get to keep Tula,” said Loza, smiling broadly. “And I will, of course. She’s the best partner ever.”

Posted 8/1/13

Summer crimes hit LA’s promenades

August 7, 2013

The news of last weekend’s tragedy on the Venice boardwalk had scarcely broken when Finbar O’Hanlon began fielding the inevitable calls.

“I’m from Australia,” says O’Hanlon, a tech entrepreneur and musician who relocated eight months ago to Venice, “and my friends from overseas were all, ‘Come home! It’s not safe! What are you doing, living there?’ “

Across town, on Hollywood Boulevard, Silvia Figueroa is hearing a similar message. In June, a troubled panhandler stabbed a young woman to death on the Walk of Fame, a few feet from where Figueroa hawks bus tours of homes of the stars. Since then, she says, her mom in Echo Park hasn’t stopped calling—and it didn’t help when a so-called “bash mob” tore down the boulevard in July, randomly robbing people.

“She keeps telling me it’s not safe,” says Figueroa, who, at 23, is the same age as the stabbing victim. “She doesn’t want me to work in Hollywood anymore.”

It’s been an unsettling summer in Los Angeles’ tourist hotspots, with three high-profile violent incidents—the stabbing, the hit-and-run and the “bash mob” robbery spree—in two of L.A.’s most famous promenades.

Not so unsettling that the tourists have stopped coming—visitors from around the world jammed the Walk of Fame this week as usual, interspersed with the inevitable hustlers in Star Wars and Mickey Mouse costumes. And Venice’s beach carnival atmosphere was back within 24 hours after a transient plowed a 2008 Dodge Avenger onto the boardwalk Saturday, veering around traffic barriers to kill a 32-year-old Italian honeymooner and injure 16 others.

But the incidents have been worrisome enough to incite calls this week for improved security measures.

On Tuesday, the Los Angeles City Council voted to augment existing traffic barriers by temporarily blocking more of the nearly 30 streets and alleys on which cars can reach the boardwalk, and to study the possibility of more permanent barriers. Meanwhile, in Hollywood this week, local business representatives plan to present a set of recommendations to Mayor Eric Garcetti aimed at making the Walk of Fame and surrounding area safer.

The list, drawn up by Hollywood’s business improvement districts and Chamber of Commerce, asks, among other things, that the city’s aggressive panhandling ordinance be reviewed and tightened, that sidewalk CD vendors and tour operators be banned from Hollywood Boulevard and that street performers around Hollywood and Highland be required to register with the city, kept to a designated limit and banned from wearing masks.

Los Angeles Police Commander Andrew J. Smith says the demands are understandable, given the crimes’ shocking nature. But, he says, the incidents are anomalies in areas that already have extensive security. The LAPD, he says, has had 20 to 40 extra officers deployed in Hollywood since the June stabbing, “on bikes, cars, foot and horseback”, and deployment is “already robust” in Venice.

“Crime is down across the board in Los Angeles,” Smith notes. “And both Hollywood and Venice are extraordinarily safe, especially compared to the crime rates of ten or 15 years ago. But when something like this happens that gets attention, it gives a false impression.”

That attention worries Stuart Sarbone, 73, a retired businessman who lives so close to the boardwalk that he heard the Venice crash on Saturday from inside his home. Sarbone notes that both the Hollywood stabbing and the hit-and-run down the block from his home appear to have been committed by unstable men.

Nathan Louis Campbell, the 38-year-old Colorado transient arrested after Saturday’s incident, reportedly had a history of substance abuse, and 26-year-old Dustin James Kinnear, charged with killing Christine Calderon on the Walk of Fame, was said to have been in and out of mental health treatment since childhood.

Kinnear has pleaded not guilty to charges of murder. Campbell pleaded not guilty this week to one count of murder, 16 counts of assault with a deadly weapon and 17 counts of hit and run. His lawyer said that he is “profoundly depressed that he has potentially ended someone’s life”, and called the crash “a horrible accident.”

Sarbone says the incidents point to a need for improved mental health care and an examination of L.A.’s safety net.

“There’s a lot of crazy things going on now because people are under terrible, terrible stress,” he says, watching a TV truck set up a camera near a boardwalk shrine to Alice Gruppioni, the Italian woman who died in the Saturday crash. “They have no jobs. They have no money. They get desperate.”

O’Hanlon, the Australian transplant, sees the incident as a tragic-but-rare occurrence, outweighed by Venice’s bohemian excitement. “I could live anywhere in the world,” he says, “and I choose to stay here.”

For many veteran Venetians, however, the incident was a tragic reminder of the vulnerability that comes with living in a community in a tourist destination.

“This isn’t supposed to happen here,” said resident Rachel Shapiro, stopping during her morning walk at the boardwalk shrine with its flowers and candles. “Sixteen million people a year—people from all over the world—come down to this boardwalk. Nobody comes here to die.”

Posted 8/7/13

Pit bull attack unleashes a crackdown

June 25, 2013

The county hopes new measures will reduce maulings, such as one that led to the death of an Antelope Valley woman. The owner of this dog, and others, has been charged with murder. Photo/AP

Even before a 63-year-old woman was mauled to death in May in the Antelope Valley, Los Angeles County animal control officers were increasingly concerned about dangerous dogs.

Some 10,000 calls last year—about one in ten—involved biting or aggressive canines. Packs of abandoned dogs in the high desert had become an ongoing issue for livestock owners.

“We had three really bad attacks against our officers in the past year,” says Department of Animal Care and Control Director Marcia Mayeda. “In one, a sheriff had to shoot a pit bull off our officer.”

So on Monday, as part of its 2013-14 budget, the Board of Supervisors addressed the problem by approving $3.5 million in new spending on animal control. Among the priorities: nineteen new animal control officers and supervisors, extra support for vicious dog investigations and prosecutions, a half-dozen new animal control trucks, more protective equipment and an additional call center in Lancaster to more quickly field complaints and deploy help in remote areas.

“This is going to be a big improvement in public safety,” says Mayeda. “Every one of these changes is going to make a difference.”

The appropriations come in the wake of the May 9 death of Pamela Devitt, a retired office manager who was mauled to death by a pack of pit bulls during a morning walk in her neighborhood in unincorporated Littlerock. The dogs’ 29-year-old owner, Alex D. Jackson, has been charged with murder. Prosecutors say he had been growing marijuana in his home, apparently using the animals as guard dogs, and that authorities had received at least two other complaints about them in the past six months.

About $1.5 million of the new money will build and staff a new call center in the Antelope Valley, where dog packs have become a chronic problem, says Mayeda.

“A lot of people abandon animals in the desert, and they form packs and cause harm,” she says. After the Littlerock mauling, Devitt’s neighbors told reporters that they carried guns in case of dog attacks, and brought their pets inside at nighttime.

The new call center, which will be set up in a modular unit on the grounds of the department’s Lancaster office, will be staffed with a half-dozen clerks, a supervisor and two animal control officers. Among other things, Mayeda says, it will help ensure that officers in the high desert get sent to the right addresses. It also will shorten wait times for callers throughout the county, who now get routed to the department’s understaffed hotline in Downey, where it’s not unusual for them to spend up to 20 minutes on hold.

Also in the budget will be a specialized 9-person countywide unit devoted to investigating and preparing the often labor-intensive petitions required to designate a dog as “potentially dangerous.”

Three more animal control officers will buttress the department’s Major Case Unit in Lancaster, working with the District Attorney to prosecute cases, and five more field officers will be dispatched to animal control offices throughout the county.

“If we’d had more Major Case Unit officers, the guy in Littlerock might have come up on our radar sooner and we might have been able to bring a case against him sooner,” says Mayeda.

In addition, she says, an expansion of the county ordinance that defines a “potentially dangerous dog” could help avert future tragedies. Currently, a dog is labeled “potentially dangerous” if it has killed, bitten or injured a person without provocation, or if it leaves its owner’s property and kills or injures another person’s cat or dog. A proposed amendment, now in the works, would expand the definition to include attacks on livestock, a particular problem in rural parts of the county, empowering animal control officers to take a larger number of dangerous dogs off the street.

Mayeda says she’s encouraged by all the new efforts aimed at cracking down on animals—and owners—who are jeopardizing the public safety and security. “This is a big step toward getting us where we need to be.”

Posted 6/25/13

Front and center at Probation

April 4, 2013

Margarita Perez has brought experience and energy to her new high-profile job with Los Angeles County.

Unlike countless showbiz hopefuls waiting on tables or schlepping to auditions, it didn’t take long for Margarita Perez to land a Hollywood gig. Not that she even thought about breaking into the business when she hit town.

After all, her day job is now among the most important in Los Angeles government. Five months ago, after years in Sacramento, Perez was tapped to help remake the county’s Probation Department and guide its response to California’s controversial AB 109 law, which has placed thousands of former state prison inmates under the agency’s supervision.

On Thursday nights at 7, Perez can be seen hosting a news segment on KCOP-TV Channel 13 called “L.A.’s Most Wanted.” The unique collaboration between the station and the Probation Department calls on the public for tips to help track down five former convicts each week—most of them with serious raps sheets—who’ve disappeared into the community.

“I think it’s exciting,” Assistant Chief Probation Officer Perez says of the segments, which began airing last week. “It’s a great opportunity to highlight probation’s good work and engage the public in holding accountable those offenders who are not availing themselves of our oversight.”

And don’t be deceived by her looks. Although diminutive and fashionable, the high-octane Perez means business. She’s a self-described former “gun-toting parole agent” who broke into the criminal justice system as a guard at Avenal State Prison, a men’s institution in Central California. As an officer in the California National Guard, she was awarded a Bronze Star for meritorious achievement after entering Iraq with the front-line troops during Operation Desert Storm in 1991. “I’m as gung-ho as they come,” she says.

Perez says her parents, born and raised in Mexico, “drove into my head that your success revolves around you. There are no crutches. If you’re not successful, then you didn’t take advantage of the opportunities in this country.”

That advice propelled Perez through the California corrections bureaucracy during a career of more than two decades. Last year, she was put in charge of the Adult Parole Operations Division, where she was responsible for 3,500 employees and a budget of about $650 million.

But that job was increasingly looking like a dead end because of AB 109, the so-called “realignment” law enacted to ease overcrowding in the state’s 33 prisons and save money. As supervision of certain newly released inmates shifted to California’s counties, there was less work for state parole officers, who increasingly faced layoffs. Perez says the number of state-supervised offenders plummeted from 128,000 to 50,000, with only more of the same ahead.

So Perez was ready for a new challenge, a desire that made its way to Los Angeles County Probation Chief Jerry Powers, who assumed the top job in October, 2011, with a mandate to not only implement AB 109 but to also shake-up a department rife with personnel and financial problems. For months, he’d been unable to field a top management team with the expertise he believed necessary to tackle the enormous issues confronting the agency.

“To be honest, I was wearing down,” Powers says. “I was trying to cover the entire house with just me.”

But late last year he found his reinforcements in Perez, whom he hired to oversee adult and juvenile field operations, and in Sacramento County’s former probation chief, Don Meyer, whom he put in charge of the department’s juvenile halls and camps, which had a history of problems so severe that the U.S. Justice Department was compelled to intervene.

Powers says his two new assistant chiefs, outwardly, couldn’t be more different.

“She’s like a tiny little dynamo,” he says. “She talks fast, she walks fast, she works fast. Everything about her is fast.” Meyer, on the other hand, is “a beast,” Powers says, a “barrel-chested” weightlifter who’s competed in and won international law enforcement competitions.

“It’s ridiculous when they stand side-by-side,” Powers says with a laugh. But both, he adds, share this in common: “They get things done.”

Of the two, Perez will certainly play a more visible role—even beyond her TV spots—given the rising concerns and controversy over the potential impact of AB 109 on public safety.

In recent months, two high-profile crimes were allegedly committed by suspects sent to the county for supervision after serving prison terms for non-violent, non-serious, non-sexual offenses. Under the new law, prior criminal histories are not considered when determining an inmate’s post-release supervision, except for high-risk sex offenders, sexually violent predators or “mentally disordered” offenders, who remain under state supervision .

In December, one of the county’s new wards was charged with a quadruple murder in Northridge. Then, just last week, another was named as the prime suspect in the kidnapping and sexual assault of a 10-year-old girl. He remains at large.

Critics of realignment have suggested that such crimes might not have been committed had the state not hurriedly foisted AB 109 on the counties—a contention disputed by most law enforcement officials, including Powers. He says that in 2010, the year prior to AB 109’s passage in Sacramento, more than 170 men were arrested in Los Angeles County for murder while under the supervision of state parole officers.

“If you take 11,000 offenders from the state and put them in Los Angeles County, you can predict that a portion of those offenders are going to kill people and you can predict that a portion are going to rehabilitate themselves and never get in trouble again,” Powers says. “So whatever your philosophical perspective, you can make a prediction and be right because the population we’re dealing with is so large. Having said that, the question is: Can we handle this population with better outcomes than the state?”

Perez says the disclosure that the alleged Northridge gunman was an AB 109 offender came during her first weekend on the job. Some of the probation officers, she says, were shocked because they’ve been mostly accustomed to dealing with lower-level offenders. Not her.

“In parole, this was a regular occurrence. You literally become accustomed to it,” she said the other day from the department’s drab and dated Downey headquarters. “Whether you’ve got a parole agent watching you or a county probation officer watching you, you’re going to commit a crime if that’s your intent.”

She says she tells her probation officers that a good number of the offenders they’re now responsible for supervising were once under probation’s watch for less severe crimes. “The only difference,” she tells them, “is that they’re a little older, their rap sheets are longer and they’re more sophisticated. But it’s the same population you dealt with.”

Perez says she also wants to assure the public that her agency “is ready to take on this challenge. We’re familiar with this population in terms of their risks, their needs and what we need to do to assist them in their reintegration into the community, realizing there’s always going to be some who are either not ready or not amenable to the resources and interventions we can provide to them.”

Perez says was one of her biggest challenges is how the agency can quickly build an infrastructure to handle the new supervision demands, ranging from training and hiring scores of new probation officers to modifying computer systems to improve tracking of the county’s new charges and their progress—or the lack of it.

Also at the top of the list is the screening and training of 100 probation officers who’ll be given guns, a first for the department.

“When I was a parole agent, I carried a caseload and I carried a gun,” Perez says. “The job was to make random house calls in the evenings, during the day, on weekends. And to go into some of those communities that are sometimes dangerous, gang infested, they are just not the safest places in the world. So if there’s an expectation that probation officers are going to do this, you have to give them the tools.” So far, she says, 28 probation officers have been cleared to carry firearms.

Perez says one of her other challenges, on a personal level, will be to find time to continue her practice of Bikram, or “hot,” yoga—27 postures practiced in a room with temperatures exceeding 100 degrees. Perez, a youthful 50-year-old, acknowledges that she practically vibrates with energy.

“You should have seen me before I started yoga,” she says. “It helps me refocus and keep my calm. It gives me a chance to go on autopilot and think about nothing.”

Even if it’s only for a couple of hours.

Posted 4/4/13

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink