Spotlight Story

New beach rules could be game-changers

June 15, 2011

It’s harder than people think to set a trend in Southern California. Take the quest to establish beach tennis at, well, the beach.

It’s harder than people think to set a trend in Southern California. Take the quest to establish beach tennis at, well, the beach.

Five years ago, a small group of South Bay tennis pros picked up the sport, a cross between beach volleyball and regular tennis that has long been popular in South America and Europe.

“It’s a natural,” says Donny Young, a Hermosa Beach early adapter, who heard about the sport from a fellow tennis pro, who had learned it from a European player. “Easier than tennis, easier than volleyball, you’ve got the sand and water and sun, and it’s inclusive.” Within a few months, Young says, he had regular matches and friends and onlookers were clamoring to play.

But since 2008, Young and his fellow enthusiasts have been struggling to find spots on Los Angeles County beaches where they can reliably volley their extra-light balls and swing their extra-short racquets. The reason? A combination of old rules and new competition for coastal space.

“Beach tennis is just one piece of it,” says Kerry Silverstrom, chief deputy director of the Los Angeles County Department of Beaches and Harbors. Beach attendance, she notes, has risen to record levels during the past five years. According to the latest figures from the county fire department’s lifeguard division, some 50 million people so far have come to the county beaches during the 2010-11 fiscal year, even with the chilly weather that dampened attendance last summer; that’s more than a 25% increase over 2005-06 beach attendance.

Part of it has to do with the economy, which has kept locals close to home during summer vacations, she says, but part is simply population growth and California lifestyle.

Ask Silverstrom to elaborate, and she’ll offer a litany of the many interests that, in recent years, have come to vie ever more intensely with swimmers and sunbathers for space on the county’s 80 or so miles of coastline: beach soccer, beach volleyball, surfers, bodyboarders, skimboarders, paddle boarders, hang gliders, kiteboarders, surf skiers, triathletes, bicyclists, filmmakers, surf camps, boot camps, cheerleading camps, day camps, weddings, Bar Mitzvahs, memorial ceremonies—“you name it,” she says. And that’s not including the non-human beachgoers from grunion to protected shorebirds who can’t be disturbed in their roosts.

As a result, the county’s Beach Commission and the Department of Beaches and Harbors have been working on an overhaul of the county’s beach ordinance, a wide-ranging set of new rules expected to come before the Board of Supervisors in a couple of months.

The idea, says Silverstrom, is to make the existing ordinance more flexible and inclusive. “Most of its sections,” she says, “have been in place since 1969.”

Rules about watercraft and beach ball sizes are being reconsidered, she says, as are special requests from the film industry and other important economic interests.

“It’s a balancing act, though,” she says, laughing. For example, a recommendation giving beach authorities leeway to give certain privileges to film crews—letting them drive on the sand under certain circumstances or launch personal water craft from the sand that are otherwise banned from operation within 300 yards of the shoreline—had to be rethought when the beach they had in mind turned out to be home to the threatened snowy plover.

Few have followed the give and take more closely, however, than the beach tennis constituents.

Popular for at least 30 years on the beaches of South America and Europe, beach tennis is played on the sand by 2-person teams who volley a soft, low-pressure ball over a high net. Players wear board shorts and bikinis; polite tennis applause is less common than rock music.

The sport began to garner publicity in the U.S. when a New York real estate developer began promoting it in 2005 on Long Island. Young and other local enthusiasts say the sport spread to Southern California when South Bay tennis pro Joe Testa took it up and recruited Young and another tennis pro, Marty Salokas, the following year.

By 2008, beach tennis had enough West Coast players to justify a tournament and some media attention. “But once the tournament was over, there was nothing,” says Salokas. “It just didn’t have the grass roots here.”

So the group began putting up flyers, sending out emails and—crucially—organizing meets on South Bay beaches, using vacant beach volleyball areas or portable nets and equipment that they would buy from the East Coast promoters and set up in the sand themselves.

So the group began putting up flyers, sending out emails and—crucially—organizing meets on South Bay beaches, using vacant beach volleyball areas or portable nets and equipment that they would buy from the East Coast promoters and set up in the sand themselves.

The impromptu courts worked well in some spots—Hermosa Beach, for example. “But anyone who tried to play in Manhattan or Redondo or El Segundo or other places was told, ‘Hey, you just can’t set that up anywhere you want’,” Salokas says.

Moreover, they discovered that the existing beach ordinance makes it illegal to throw, kick or roll anything on the sand that is smaller or denser than a 10-inch inflatable rubber playground ball. So the group began lobbying beach cities and the county for an exception.

They scored in Hermosa, where last year two beach tennis courts were designated by the city. But Lucy Streeter, a private swim instructor and former professional high diver from Rancho Palos Verdes who helped organize the grassroots efforts, says their pleas to the county initially got lost in the larger beach ordinance revision. So several months ago, the group launched a petition drive and a letter writing campaign.

Now, officials say, they are definitely on the radar, and stand to benefit from the new rules, if they are approved later this summer.

“We have staff currently looking for locations where we might put a permanent beach tennis court or two,” says Silverstrom, suggesting Malibu’s Zuma Beach or Dockweiler State Beach near Marina del Rey.

That’s good news to people like Streeter, a mother of three who took up the sport because it seemed so easy.

“The hardest part about it,” she says, “has been finding a place to play.”

Posted 6/15/11

How the public won a Malibu sand fight

June 7, 2011

It started last summer in Malibu with a fight between surf camps and led through a black market to a legislative mystery.

It started last summer in Malibu with a fight between surf camps and led through a black market to a legislative mystery.

But the long, strange trip that this year led Santos Kreimann to the discovery of a mistake that was costing Los Angeles County hundreds of thousands of dollars is now offering the intrepid director of the Department of Beaches and Harbors a possible long-term fix for this summer’s first pressing problem: how to keep the beach bathrooms open and clean.

County beach maintenance workers came under fire last week in one of the more publicized sidebars to the county’s ongoing budget challenges. Amid complaints about scaled-back cleaning schedules, late openings and locked doors at the county’s 52 beach restrooms, Supervisors Zev Yaroslavsky, Gloria Molina and Don Knabe called for alternatives.

The discussion generated headlines and local talk radio furor. On Tuesday, Kreimann presented the Board with a short-term plan to delay some hiring and maintenance and to use marina lease-option and lease-extension fees to open more bathrooms earlier and beef up summer cleaning crews.

Less widely-known, however, was the story behind the long-term proposal Kreimann hopes will help pay for not only the bathroom maintenance, but for other beach services going forward: a change in the county’s longstanding permitting system for recreational beach camps.

At issue, Kreimann says, is the way the county allocates beach space to the hundreds of interest groups that do business on the sand each year, including legions of surf camps and summer recreational programs that traditionally have received permits according to seniority.

For-profit programs are required to pay a small percentage of their gross receipts in exchange for the permits. That assessment, however, has been waived in past years for city-sponsored programs and non-profit organizations; they’ve paid only a modest administrative fee for the privilege of setting up shop on county beaches. “But there are non-profits, and there are non-profits,” says Kreimann. “Some of these camps charge like $600 a week.”

With public revenues dwindling, he says, those non-profit programs looked like an untapped source of revenue. But when Kreimann, who was appointed director in 2009, inquired about the issue, he was told by staffers who’ve since retired that the nonprofits couldn’t be charged because state law prohibited the county from assessing fees on youth groups.

Then last summer, he says, a surf camp in Malibu resurrected the beach permit question when its owner called to demand that an unpermitted rival be thrown off the sand. “The camp operators got into a physical altercation over allegations that one was operating illegally,” Kreimann says.

Allen King, co-owner of Aqua Surf camp, says the set-to was more like “harassment.” But he confirms that the dispute arose from the beach use permitting policy—in this case, the seniority system, not the fees.

As surf camps had proliferated in recent years, beach permits had become highly valuable, and anyone who had one was reluctant to relinquish it to make space for newcomers. When the City of Santa Monica, where King had operated for more than a decade, decided to decrease surf camp permits to reduce beach crowding, King says, he found it impossible to break into the county beach space.

“We tried to get a county permit, we wrote letters, but it was a closed system,” King says. “Whoever got one first would just hold onto it forever, and nothing moved.”

King’s solution: to cut a deal with a permitted surf camp. He says he offered to expand the business of Kanoa Aquatics, based in the South Bay, by setting up shop to the north, on Surfrider Beach in Malibu under Kanoa’s brand.

After a year, however, the relationship soured, according to both parties, and got downright ugly after King returned to Surfrider—without a permit—the next summer, setting up shop right next to the spot where Kanoa’s owner, Kip Jerger, was now operating on his own.

“I got a little personal,” Jerger acknowledges. “In a way I’m sorry but in a way I’m not. I was like, ‘You guys are like sharks coming in from the ocean.’”

King, meanwhile, says he was just “taking a stand” against an unfair permitting system, only to be confronted by his former colleague. “They were out there yelling, ‘You’re illegal! You’re not allowed to be here!’” King says. “You could have built a reality TV show around it, it was so dramatic. No one got into a fistfight, exactly, but someone did throw a rock at our tent, and we have witnesses.”

Kreimann of the beach department says that when the dispute landed on his desk, he felt compelled to revisit the permitting system. Clearly, beach use had to be limited, but the seniority system was creating problems of its own. Some 50 camps had been waiting years for a spot on one of the beaches, and existing permits had been issued and reissued “with no real safety standards.”

“Multiple people were subcontracting their permits,” he says. “A black market is a pretty good analogy.”

And, he learned, only about 30 of the 162 permit holders were paying a share of their gross receipts to the county because of the state legislation that supposedly prevented the county from charging nonprofits.

“So three or four months ago, I said to my staff person, Penelope Rodriguez, ‘Find that law.’ ”

She couldn’t.

Rodriguez, a program manager, says she quizzed colleagues and searched files and databases, but “we didn’t have the actual bill in any files and nobody remembered the year or the author or what group had introduced it.”

Finally, she says, she traced the confusion to a bill from the mid-1990s that had gotten through the legislature before the governor took issue with a provision that said youth groups not only shouldn’t be assessed like for-profit beach camps, but shouldn’t need the same liability coverage.

“It turned out that the law had been vetoed,” says Kreimann. “We should have been charging them all along.”

Kreimann says the faulty legal assumption was “an oversight” by otherwise hardworking employees, the last of whom retired earlier this year. “The actual law was right there in our file when we went back to check it, but they had misunderstood it. It was one of those things you discover when people leave and you get a new set of eyes.”

Since then, a plan to revamp the system and to set up a competitive selection process for summer permits, based on minimum standards set by the county lifeguards, has been working its way through a series of Beach Commission meetings. A workshop was held in early spring.

Jerger, who has had his beach permit for 14 years, says he understands the need to raise revenue—in fact, he works part-time for the county as a recurrent lifeguard. But he predicts a change in the system will let in more camps and worsen beach crowding, which, thanks to the stalled economy, is already at record levels. (According to the County Fire Department’s lifeguard division, attendance last year topped 68 million, nearly double the 38 million beachgoers counted in 2005-06.)

And levying a percentage of gross receipts on nonprofit recreational programs, he says, could force him to start charging the families of hundreds of disabled and needy children, to whom he’s been giving a break on tuition.

King, on the other hand, says he’s glad to ante up if it means getting a permit.

For his part, Kreimann says the assessment will not only add a measure of fairness and oversight to the beach camp landscape, but could net “in the neighborhood of $500,000 a year, conservatively.”

A recommendation is expected to come before the Board by the end of August. Kreimann says it’s too late for the plan to cover the estimated $372,000 it will cost to revamp the cleaning schedule for this year. But if consensus is reached, it could make the summer of 2012 more convenient and fragrant.

And any surplus could go toward Kreimann’s next plan for getting the most out of the county beaches: “A lot of our parking machines are down a lot of the time, and if we replace them, it could really increase revenue.”

Posted 6/7/11

Behind the scales at “The Biggest Loser”

May 24, 2011

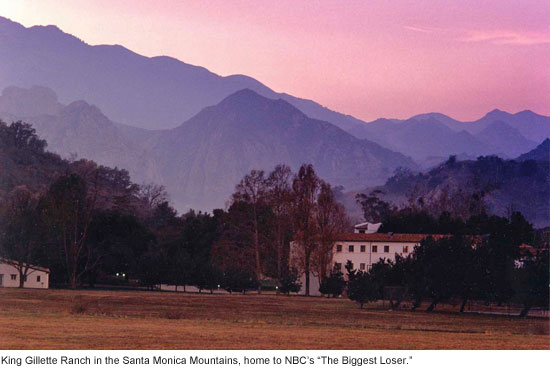

On the hit TV show “The Biggest Loser,” it’s known simply as “The Ranch”—a serene, sprawling property where thousands of pounds and decades of shame have been shed during the past four years.

On the hit TV show “The Biggest Loser,” it’s known simply as “The Ranch”—a serene, sprawling property where thousands of pounds and decades of shame have been shed during the past four years.

For months at a time, the mountainous acreage is home to dozens of contestants who battle their demons and their weight to gain the title of “The Biggest Loser,” along with a tidy purse of $250,000. But the property, complete with its Hollywood-imported state-of-the-art gym, is no ordinary production set.

Unbeknownst to the NBC show’s millions of fans, who’ll be tuning in for tonight’s finale, “The Ranch” is one of Los Angeles’ most historic and dazzling properties, designed by famed architect Wallace Neff in the late 1920s for razor-blade tycoon King Gillette. In 2005, an unprecedented coalition of government agencies, including Los Angeles County, raised $34 million to protect the ranch’s 600 oak-studded acres from expansive development.

Located along Mulholland Highway in Calabasas, King Gillette Ranch is being transformed into a gateway destination for the Santa Monica Mountains recreation area. A new visitor’s center currently is under construction there. The property is operated by the Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority, which receives $50,000 a month from the show to help underwrite the agency’s operations throughout the region.

Managing the property for the MRCA is ranger Scott Hughes, a fit and trim Army veteran who has the tricky job of ensuring that the public has unfettered access to the property—including dozens of grade-school campers—while helping the show’s producers create an illusion of exclusivity and privacy. Talk about your mixed-use property.

“There’s no effective job description for this position,” Hughes says. “I add something new to it every day.” One thing, however, remains a constant above all else, he says. “It’s my job to protect this property.”

Living on the grounds with his wife and a 15-year-old son, Hughes has gotten to know not only the production crew but each of “The Biggest Loser” contestants, some of whom arrive weighing nearly 500 pounds and carrying a heavy psychological burden that has been with many of them since childhood.

“Season after season, you see them around the property,” Hughes says. “You can see the sadness in their eyes.” But then, after weeks of healthy dieting and high-intensity workouts, “you can literally see their spirits lift. It’s an amazing transition.”

There’s also been a fair share of drama on the ranch, including romances and, this season, the abrupt departure of one of the contest’s frontrunners—former Olympic wrestler Rulon Gardner, who won a gold medal in the 2000 Sydney Summer Games by beating the seemingly invincible Russian Alexander Karelin.

Gardner, 39, came to the ranch weighing 474 pounds, 200 more than during his storied wrestling career. In late April, after having lost 188 pounds, he announced during the show that he was going home “for personal reasons”—the first contestant to voluntarily walk away from the ranch, leaving behind mystery and speculation about his hasty exit.

“The Biggest Loser’s” relationship with the ranch began shortly after it was acquired as public land from the previous owner, Soka University, which had been blocked in its plan to expand the campus to accommodate some 5,000 students. The show’s crew had come to film a single competition, or “challenge,” between the contestants in season four.

But the producers quickly recognized that the property’s beauty and its structures would represent a substantial upgrade. Back then, contestants were living in the state’s old mental institution in Camarillo. Now they’d be bunking in an annex to the Gillette mansion built in the late 1950s for an order of monks by one of the ranch’s several owners over the decades, who have included MGM director Clarence Brown and church leader Elizabeth Clare Prophet.

On a recent day at the ranch, the “Biggest Loser” crew was busy preparing the place for the upcoming season, which starts production in early June. The kitchen, with its to-die-for appliances, is being redone, as are the “living room” and the bedrooms. Ranger Hughes was making sure that a dead oak limb was carefully cut by his staff so that it would not collapse on an outdoor table where interviews with contestants are sometimes filmed.

Despite all the activity, Hughes says, “this is the calm before the storm. The storm is when there’s 80 to 100 people here.”

Posted 5/24/11

L.A. firehouse food brings healthy heat

May 17, 2011

When President Barack Obama lunched earlier this month at a fire station in Midtown Manhattan, he sat down to pasta in cream sauce and eggplant parmesan—traditional New York firehouse fare. Too bad for his waistline he didn’t roll West Coast-style with Sheila Kelliher and her fellow Los Angeles County firefighters.

When President Barack Obama lunched earlier this month at a fire station in Midtown Manhattan, he sat down to pasta in cream sauce and eggplant parmesan—traditional New York firehouse fare. Too bad for his waistline he didn’t roll West Coast-style with Sheila Kelliher and her fellow Los Angeles County firefighters.

“We do a lot of grilling,” says Kelliher, a firefighter-paramedic at West Hollywood’s Station 8, where the take on firehouse cuisine is a far cry from the carb-heavy comfort fests dished up at fire stations in other parts of the country.

“Chicken, fish, pita breads, salads. Eleven years ago, when I first came on the job, it was meat and potatoes, but now healthier food is the trend. At least it is here.”

Kelliher should know. Last month, her quietly healthy recipe for Texas chili won the Barney’s Beanery First Annual Five-Alarm Firefighter Chili Cook-Off, a region-wide contest launched by the restaurant in honor of its 90th anniversary.

The recipe—a secret concoction of grilled tri-tip, red sauce, “no extra fat and not too many black beans”—was so delicious, yet light, that, starting June 1, it will appear on the Barney’s Beanery menu. Proceeds will benefit the Alisa Ann Ruch Burn Foundation, a nonprofit for burn survivors.

“Her chili was just very flavorful, it wasn’t too heavy and it wasn’t overloaded,” says the restaurant’s regional manager A.J. Sacher in a description that firehouse food experts say could easily sum up the philosophy of Southern California firefighters.

“In Chicago, they’ll grind up four pounds of meat and put in some macaroni and call it dinner,” says Jeff Gatesman, the West Los Angeles producer of “Feeding the Fire,” a web-based TV cooking show featuring firefighter chefs from across the country.

“But it’s a whole different story in California. We just shot an episode in Santa Monica and the guy made, like, pan-seared sea bass.”

Firehouse cooking is a venerable institution, particularly in cities where firefighters bunk in the fire station for 24-hour shifts that last several days.

“They work together, they sleep together and they break bread together,” says R.G. “Bob” Adams, author of “Firehouse Cooking: Food From America’s Bravest,” an international compilation of firefighter recipes that he says has sold more than a million copies since its first publication in 1993.

“The chef in a firehouse is the hub,” says Adams. “Kind of like the mother in a family.”

And like mothers everywhere, firehouse chefs are stewards of a community’s priorities and sub-cultures, from ethnic traditions to attitudes about nutrition and weight.

Long Beach Fire Capt. Eddie Sell, who is developing a cooking show for television called “Firehouse Chefs,” says that because firefighters have increasingly reflected the diversity of cities, firehouse meals “open the door to a city’s customs, so that when we have to make emergency calls to peoples’ homes, things aren’t as foreign.”

Where an East Coast firehouse might specialize in Italian feasts and a Southern company might be famed for rich desserts and gumbos, Sell says, West Coast stations will line up for pho and fish tacos.

“And definitely, there’s more heart-healthy stuff on the West Coast,” adds Matt Jackson, a West Covina firefighter-paramedic whose year-old Company Chow blog has become a recipe clearinghouse for firefighters from New York to Hawaii.

“Some crews I’ve worked on, the guys will have, like, gluten-free diets, or they’re not eating any simple sugars. Last year, ‘Live! With Regis and Kelly’ had a firefighter barbecue cook-off, and the California firefighter’s entry was actually a salad with barbecued pears.”

Kelliher, a Woodland Hills mother of 8-month old twins who does competitive bodybuilding in her spare time, says health is a priority at her station. (Check out one of her recipes here.)

Kelliher, a Woodland Hills mother of 8-month old twins who does competitive bodybuilding in her spare time, says health is a priority at her station. (Check out one of her recipes here.)

“Our county leads the charge when it comes to fitness,” she says. “We have a program called Fitness for Life. We have to pass a physical every year and meet certain benchmarks.

“And L.A. life is all about healthy lifestyle—a lot of our guys surf and snowboard and go to the river. Colder parts of the world, you don’t to do those things year-round, you’re covered up, maybe you eat more comfort food. But here, you hit the beach, the shirts come off and vanity kicks in.”

The 13 firefighters on her shift take turns at kitchen duty, she says: “Everybody puts in their money for chow—$12 for two meals, $7 for one meal—then whoever is the cook takes the money and goes to the store.”

All firehouse meals must meet two basic criteria, she says: “You can’t come up short, and it has to taste good.”

But health is a given, even for the younger firefighters who can eat as much bread as they want to. Grilling—which allows the fat to drip away from fish or meat during cooking—is such an art form at Station 8 that a few years ago, the whole crew chipped in and built an outdoor barbecue and grill station. “Everybody has their own specialty,” she says.

As for that special chili, she entered it in the contest at the behest of a friend, who knew it as something that Kelliher, who grew up in a family of Texas restaurateurs, served at Superbowl parties. Kelliher did her cooking off-duty and pressed her husband into helping her to serve massive quantities of the chili during the competition. It’ll be on the menu till September at all five of Barney’s Beanery locations in Los Angeles County.

Which may be the only chance her fellow crew members get to taste it. Ironically, she’s never served it at the firehouse. “It’s too labor intensive,” she said.

Posted 5/17/11

Probation teens chart a fresh start

May 13, 2011

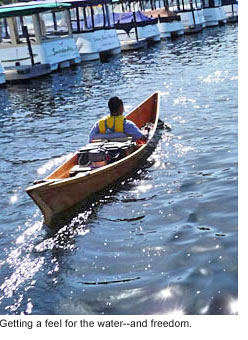

For seven months, Ty Kastendiek’s kids have been readying the Miss Ann for this weekend. Some 20 pairs of young hands have helped build her — hammering, sawing, sanding, varnishing.

For seven months, Ty Kastendiek’s kids have been readying the Miss Ann for this weekend. Some 20 pairs of young hands have helped build her — hammering, sawing, sanding, varnishing.

Fifteen-feet-long, made of wood, she gleams in the sun and all but flies through the water. And to take her out is to know something Kastendiek’s kids appreciate perhaps more than most Southern California boaters: the joy of being free.

Kastendiek—or “Mister Ty”, as his students call him—is a veteran teacher at Camp David Gonzales in the hills above Malibu. Although he has been many things in his life—a purchasing executive, a contractor, an NCAA volleyball player, a Malibu surfer—he has spent the last 18 years teaching history, math and science to incarcerated teens for the Los Angeles County Office of Education. Last summer, he says, he was clicking around on the web when he came across an item about a boat race for high school science students.

“I thought, ‘I like boats’,” he laughed. “I also thought, ‘Yeah, and this would be a long shot.’”

Still, he couldn’t resist taking a closer look at the contest. Sponsored by the Metropolitan Water District, it required participants to build a solar-powered boat, write papers on the science behind it, pull together an environmentally-oriented public service ad and finally race the boat at a grand finale.

It would be tough, Kastendiek realized. Past winners tended to come from affluent suburban school districts, not juvenile lockup. But now, against all odds, he and a team of Gonzales students have cleared every hurdle and then some.

On Saturday and Sunday, they will compete against some 800 students from 40 Southern California high schools in the 9th annual Solar Cup at Lake Skinner in Temecula Valley.

“We’re rookies,” Kastendiek admits, “but I think we’ll make a respectable showing.”

“It’s exciting,” confides one of the teenagers on the team, a soft-spoken 18-year-old from Newhall named Richard who joined the project two months ago, toward the end of a 9-month stint at Gonzales.

“I’ve never been on a boat like this before,” he said, smiling broadly during a test run this week in Westlake. “I thought I was just going to do my time and go home.”

“I’ve never been on a boat like this before,” he said, smiling broadly during a test run this week in Westlake. “I thought I was just going to do my time and go home.”

Solar Cup coordinator Julie Miller says the contest started as part of the outreach when the MWD was opening the Diamond Valley Lake reservoir in Hemet for recreation. The contest—part regatta, part science project—permits rookie teams to spend up to $4000 on their boats; more veteran teams are limited to $2,500 since, after the first year, they have most of the required parts.

Though only eight boats entered that first year, the Solar Cup is now the largest race of its kind in the nation. Miller says she frequently hears from former contestants. A member of one of the 2007 teams recently wrote to credit the Solar Cup with her decision to become an engineer, says Miller. Two more students who entered as part of a 2008 continuation school team e-mailed to say that the project had inspired them to go on, respectively, to the military and community college.

But this year’s race is the first to feature a team of incarcerated students, and there were some initial hurdles. For one thing, Kastendiek needed a water agency to sponsor the cost of boat building. At the MWD’s suggestion, he called the Las Virgenes Municipal Water District, which stretches from Woodland Hills to Westlake Village.

He wasn’t optimistic. Rules for rookie teams included attendance at two mandatory boat-building workshops; his team couldn’t travel without at least two sworn probation officers to oversee them. Most teams videotaped their public service announcements; his kids’ faces couldn’t appear on film due to court-ordered confidentiality restrictions.

Other teams could make their boats a yearlong class project, but the kids on his team came and went from Gonzales throughout the school year. The teenagers who built and designed the boat in November would not be the same teenagers racing it in May.

But Kastendiek’s call was music to the ears of the Las Virgenes district board members, says public affairs associate Deborah Low.

“We had tried in the past to engage the other high schools in our service area, both public and private, and had never found anyone who wanted to do it,” Low says.

The district’s one request was that the boat be named for the late Ann Dorgelo, a longtime board member from Agoura Hills who had advocated teaching local school children about water conservation.

The boat building began at the start of the school year, with seven or eight students chosen for their interest, their attitude and for their ability to maintain focus and calm, Kastendiek says.

MWD gives each team a basic kit, but the boats vary widely in their look and engineering. The Gonzales boat had to be almost entirely made of wood because the camp doesn’t have a machine shop or welding equipment. Also the design had to be simple—few of the Gonzales kids had ever even been in a boat, let alone built one.

Blueprints were drawn; calculations made. Kastendiek then won permission to take seven or eight kids (with the appropriate supervision) to the official boat-building workshop in early November.

“We built it in about five and a half hours,” he recalls proudly. “Some of those kids had never sawed wood before.”

The team, however, was every bit the revolving door that Kastendiek had feared.

A couple of the boat-builders got into trouble for fighting or defying other teachers and lost their spots. Others were so calmed by the project that they were sent home early for good behavior.

Kastendiek says he tries not to know too much about his students’ back-stories, the better to give them a fresh start. But working with them day in and day out, it was hard to stay at arm’s length from their struggles. One kid who had thrown his heart and soul into the boat lifted his shirt one day to show Kastendiek the scars from five bullet wounds on his torso. “He told me he was glad he’d been locked up,” the teacher remembers, “because if he hadn’t he’d be dead by now.”

Kastendiek says he tries not to know too much about his students’ back-stories, the better to give them a fresh start. But working with them day in and day out, it was hard to stay at arm’s length from their struggles. One kid who had thrown his heart and soul into the boat lifted his shirt one day to show Kastendiek the scars from five bullet wounds on his torso. “He told me he was glad he’d been locked up,” the teacher remembers, “because if he hadn’t he’d be dead by now.”

By the New Year, the first crew of boat-builders was nearly gone from Camp Gonzales. Again, Kastendiek reached out. Several artistic kids came on to do an interactive print brochure that the group settled on as their public service announcement. (“I told them, “Let’s play to our strength—we have some of the best taggers in L.A. County’,” jokes the teacher.)

The laminated, flexagon-style brochure ended up winning a top prize in the rookie category of the public service part of the contest.

More fresh troops completed the boat’s construction. “Some of these kids were almost borderline hyperactive, and you’d put sandpaper in their hands and after a while, you could see their shoulders drop and all of a sudden, a joy there,” Kastendiek remembers. Still other students discovered a sudden affinity for math in the course of building the boat’s solar-powered engine.

Finally, this week, the boat was ready to hit the water.

“Take a deep breath. Take your time,” Kastendiek urged three team members this week at the Westlake Lake test run as reporters, water district board members, probation officers and assorted dignitaries bustled around them. Someone dropped a metal wrench on the battery. A spark flew. “Don’t worry,” Kastendiek repeated. “Try again.”

Down the shore, a competing team from nearby Oak Park High School unloaded their boat, painted a cheery yellow. Kastendiek’s kids watched from a distance in their orange camp-issued shorts and gray t-shirts as the suburban team confided that they were short-staffed because the AP Physics exams were being held that day.

But on the water, the Miss Ann seemed equal to almost any challenge. Christian, an 18-year-old from Long Beach, and Marco, a 16-year-old from Pomona, laughed out loud as she gathered speed.

“It was thrilling! It was so smooth, and the rudder was so simple,” their teammate Richard marveled as he finished his turn as skipper. None had ever steered a boat before that afternoon, said Kastendiek, who was smiling, too, as they loaded the Miss Ann back onto her small trailer.

“I hope we can make a loud statement that these kids have potential,” he says. “And I hope we can come back again next year.”

Posted 5/11/11

It’s not easy being Mom

May 5, 2011

Mother’s Day means flowers, candy, hugs and a full court press at Hallmark. But for many new moms in Los Angeles, becoming a mother is no brunch at the Ritz.

Data from the latest “Los Angeles Mommy and Baby Survey,” published by the county Department of Public Health earlier this year, show that despite some positive news on breast-feeding, prenatal care and post-delivery checkups, there’s trouble in Momville.

From depression to dental woes, unplanned pregnancies to prenatal obesity, the survey offers what can only be termed a mother lode of insights into new motherhood in L.A.

First, the good news. “Over 90% of the women in L.A. County receive prenatal care, which is spectacular compared to other parts of the country,” said Dr. Diana Ramos, the county’s director of reproductive health, who noted that Medi-Cal has helped to ensure that low-income women in California are covered during pregnancy. Also, 85.2% of the mothers surveyed had breastfed their babies and 98.3% took their newborn in for a well-baby check-up.

Now for the not-so-good.

The countywide survey, which canvassed 6,264 new mothers who gave birth in 2007, found that 58.1% of new mothers surveyed said they were at least a little depressed after giving birth, and 19.9% said they had been depressed for a period of two weeks or more during their pregnancies.

The countywide survey, which canvassed 6,264 new mothers who gave birth in 2007, found that 58.1% of new mothers surveyed said they were at least a little depressed after giving birth, and 19.9% said they had been depressed for a period of two weeks or more during their pregnancies.

“One of the things that is quite startling is the number of women who experience depression,” said Cynthia Harding, director of Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health Programs for the public health department, which produced the survey.

“It says that we need to provide more social support,” Harding said. “Pregnancy is a time of joy, and if you’re not feeling the joy, you might feel ‘What’s wrong with me?’”

To that end, a multifaceted push is on to increase awareness of maternal depression, reduce the stigma and train health care and other providers to better recognize the symptoms. This brochure is being distributed this month to new mothers in all hospitals across the county.

“It’s a very, very vulnerable time,” said Caron Post, director of the L.A. County Perinatal Mental Health Task Force, which is spearheading the “Speak Up When You’re Down” campaign with the Department of Public Health. “Mothers put on a happy face. It’s taboo to be depressed and be a mother.”

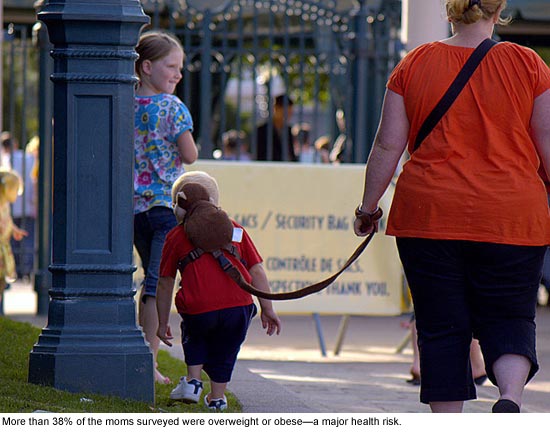

Obesity is also a big concern.

More than 38% of the mothers surveyed were overweight or obese before getting pregnant, and more than a quarter said they didn’t exercise during pregnancy.

“If there was any one call to action, it would be obesity. It’s one of the big risk factors in maternal mortality,” Dr. Ramos said. “Yes, we all know there’s an obesity issue. But I don’t think we’re doing enough to give directive advice [on keeping weight down] to reproductive age women.”

There’s also room for improvement when it comes to pre-pregnancy preparedness.

For instance, 53.4% of the new moms surveyed said their pregnancies had been unwanted or “mistimed,” and 34.1% said their husband or partner shared those views.

What’s more, 70.7% received no preconception health counseling and 54.4% didn’t know about the importance of taking folic acid supplements before and during pregnancy. And 9.6% smoked in the six months before becoming pregnant.

What’s more, 70.7% received no preconception health counseling and 54.4% didn’t know about the importance of taking folic acid supplements before and during pregnancy. And 9.6% smoked in the six months before becoming pregnant.

Not exercising during pregnancy was by far the most common “risk behavior,” reported by 28.6% of those surveyed. But other risks showed up, too, including drinking alcohol (10.5%), exposure to second-hand smoke (6.3%), smoking (2.6%) and using illegal drugs (2.4%).

In the 3rd District, women who participated in the written survey reported high rates of breastfeeding and well-baby check-ups. They were the least likely to have been overweight prior to pregnancy—and the most likely to have received fertility treatment.

They also were the likeliest to drink alcohol during their pregnancies, 12.4% compared to 10.5% countywide. Any level of drinking during pregnancy is of concern to public health officials. “It may be two or three weeks before you realize you’re pregnant. If you want to get pregnant, stop drinking ahead of time,” said county maternal programs director Harding.

Another painful finding: dental distress.

Nearly 19% of those surveyed (21% in the 3rd District) said they’d experienced periodontal disease during pregnancy. Many women can’t find a dentist who’ll treat them, especially during pregnancy, while others are fearful and put off going until the pain is unbearable, advocates said. In either case, tooth and gum infections can present a serious medical risk for mother and fetus when bacteria enter the bloodstream.

The survey is part of the Los Angeles Mommy and Baby Project, which was launched following an increase in infant deaths in the Antelope Valley, mostly among African Americans, from 1999 to 2002. After an initial 2004 pilot survey in the Antelope Valley, the project was expanded countywide in 2005.

A new survey of women who gave birth in 2010 is currently underway, and is expected to capture stresses inflicted by the current economic downturn.

“We are seeing more and more patients who have lost their health insurance but don’t qualify for any low-income programs,” said Debra Farmer, president and CEO of the Westside Family Health Center in Santa Monica.

Even among the 2007 moms, 36.7% said they had no insurance, 22.4% reported stress over unpaid bills, 13.8% were stressed out over job loss experienced by their husband or partner, and 11.6% over losing their own job.

There are concerns that as California moves to implement health reform—and to cope with a drastic budget situation—that cutbacks will diminish the level of maternity services available to those who need them most.

“I think a lot of what has been there in the past is eroding because of the economic situation and the state cutbacks,” said Lynn Kersey, executive director of Los Angeles-based Maternal and Child Health Access. “What’s going to happen during health reform is of extreme interest.”

Getting in on a royal anniversary

April 28, 2011

Not everyone in Los Angeles County will be tuned in to Friday’s Royal Wedding, compelling though the nuptials of Prince William and his bride, Kate Middleton, may be.

Not everyone in Los Angeles County will be tuned in to Friday’s Royal Wedding, compelling though the nuptials of Prince William and his bride, Kate Middleton, may be.

At least 133 local couples will probably be too busy on April 29 to check out what’s happening in Great Britain—because they’ll be having their own weddings that day.

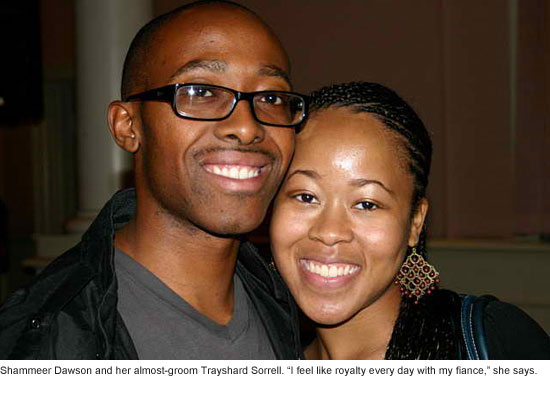

“We had no idea when we scheduled that we’d be getting married on the day of the royal wedding, but we’re happy to be having a dignified day,” laughed Shammeer Dawson, a 26-year-old USC graduate student from Gardena who will be marrying her 27-year-old fiancé, Trayshard Sorrell, at a Los Angeles County complex in Norwalk this week.

According to Portia Sanders, division manager at the Registrar-Recorder/County Clerk’s office there, the number of ceremonies scheduled for that date at county offices has shot up this year. Only 49 ceremonies were performed last April 29, she said, and only 104 were performed the next day, which, as in this year, was the last Friday in April.

Wedding fever?

Probably not, Sanders says.

“We’ve seen an increase in marriages over last year in general,” she says. “Some of it is service men and women being deployed. Some of it is the economy, people who were living together getting married now for the benefits. Some of it is just because it’s a Friday and it’s easier for people to fit into their schedules.

“What can I say?” she says, laughing. “There’s always love there, but not always romance.”

In fact, Dawson says, the couple’s first choice had been April 30, the anniversary of their first official date as a couple—dinner at P.F. Chang’s after a concert to benefit victims of the Haitian earthquake—but it fell on a Saturday. “So we chose the closest date.”

Acquainted since 2007, when they met as coworkers at an Enterprise Rent-A-Car office, they remained friends while Dawson went back to school to earn a master’s degree in social work and Sorrell worked his way up through the ranks in the car rental business.

They initially had planned to marry at Sorrell’s church in Hermosa Beach. “But we couldn’t connect with the pastor, and had difficulty booking a date, and it was very stressful,” says Dawson, who suffers from systemic lupus and was worried about her health. Plus, they wanted to marry before her graduation next month, and money was tight—in that respect, she joked, “we’re not the royal family.”

“After prolonging our date, we finally just decided to do it at the county,” she says. “I’ll be wearing a Grecian style gown, kind of a cream-white with jewels on it, and I’ll have my hair up.” Her mother and Sorrell’s cousin will witness, and the couple will leave immediately after the ceremony for a honeymoon in Las Vegas.

“It may not be Westminster Abbey, but I feel like royalty every day with my fiancé,” she says, laughing. “It’s wonderful to be in love.”

Posted 4/28/11

This budget’s a labor of love

April 22, 2011

In some parts of the nation these days, public sector unions are battling a perception that they’re the bad guys—out only for themselves as government budgets dwindle and services wither. But in L.A. County, unions have another rep—as recession-savvy partners whose sacrifices are helping to save the day.

County unions, now going into their 3rd year of working without raises, have emerged as some of the improbable heroes of a proposed $23.3 billion budget which—at least for now—includes no layoffs or furloughs. The county’s situation is particularly striking in comparison to the city of Los Angeles, where generous employee pay raises gave way to a dire economic picture including both layoffs and unpaid furlough days.

People on both sides of the bargaining table attribute the county’s situation to sound financial stewardship before the economic collapse and to long-running collaborative relationships between the unions and the county’s elected and executive leadership.

Not to mention the fact that union leaders—correctly, as it turns out—anticipated that the downturn would be long and ugly, not a short-term blip, and could jeopardize jobs.

“We saw what was coming, and it wasn’t looking good,” said Steve Remige, a director of the Association for Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs (ALADS) who was the organization’s president during the most recent rounds of contract negotiations. Doing without raises, under the circumstances, “was an easy sell to the membership.”

It was harder over at SEIU Local 721, where some members at least initially expected a shorter-lived recession. “Some thought it would be over in a year or two,” said Bob Schoonover, president of the local, which represents some 55,000 county workers “from custodians to nurses.” By toughing it out and agreeing to no raises, however, the members not only helped avoid layoffs in their ranks but also contributed to keeping public services afloat, he said.

“We agreed to a series of no-raise contracts…in order to keep services going at the level they need to be,” Schoonover said. “The county and SEIU have had a very good working relationship for the last few years. That’s to the benefit not only of the members but to the public.”

Because of the sheer size of the county workforce—salary and benefits for nearly 100,000 employees, most of them unionized, account for 40% of the budget—even a tiny cost-of-living adjustment carries a huge price-tag.

As it is, the proposed budget unveiled this week reveals a $220.9 million shortfall that the chief executive office says can be eliminated through, among other things, one-time funding, the elimination of vacant positions and department cutbacks—but without forcing anyone into unemployment.

And for that, Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky and others give substantial credit to the unions and their leadership. “They made a tough decision for themselves and for their members,” he said.

Labor and management both credit the long tenure of the board majority—and the trust that has flowed from it—with creating the climate for union concessions.

“Good labor relations demand a certain longevity,” said Blaine Meek, counsel for the California Association of Professional Employees, which represents some 2,700 county employees in departments such as Public Works, Treasurer-Tax Collector and Assessor.

So when the Board of Supervisors made it clear that without union cooperation, the county’s fiscal health would suffer and workers would lose their jobs, the unions decided to play ball.

“At the end of the day, they went along with us,” Yaroslavsky said. “I think they wanted to do something statesmanlike. And the proof of the pudding is three years later, we haven’t laid off anybody and we haven’t furloughed anybody.”

Jim Adams, chief of employee relations for the county, said the current season of labor-management harmony is no mere “kumbaya thing.” He acknowledged that labor agreements in recent years have asked county employees to do without raises at a time when workloads are increasing and vacancy and promotional freezes are in place.

“These sacrifices have strained our employees at times,” Adams said.

But those sacrifices looked more palatable when compared to what was happening in other places.

“People were seeing layoffs and furloughs all around us,” Adams said. “They were seeing worse things going on elsewhere than a salary freeze.”

The austerity contracts started in early 2009 with ALADS and the county’s other public safety unions. Setting the stage for the negotiations with other county unions that would follow, they accepted no raises and a 50% reduction in the amount the county pays in deferred compensation. But they won a larger county contribution to their rising health insurance premiums.

Now, with small signs of a recovery on the way, county union members are keeping one eye on the local economy and the other on their union brethren around the nation.

“They see that public employees have been made a target in a bad economy, even as the demand for government services is rising,” said Meek, of the California Association of Professional Employees. “Yes, our members are anxious. Even their voice in collective bargaining is under attack.”

But in their dealings with L.A. County, there is a sense that sacrifices in bad times will be rewarded when things get better.

“There is an expectation,” Meek said, “that when conditions improve that we will go forward and get back to pay raises and addressing other issues.”

Or, as the SEIU’s Schoonover puts it: “We’re all hoping we return to whatever normal is.”

Posted 4/21/11

Bikes make tracks on Metro trains

April 13, 2011

When Metro volunteers checked out the bike-toting crowds on downtown transit platforms Sunday morning, a thought straight out of “Jaws” leapt out at them:

When Metro volunteers checked out the bike-toting crowds on downtown transit platforms Sunday morning, a thought straight out of “Jaws” leapt out at them:

We’re gonna need a bigger train.

Sunday’s CicLAvia ride through Los Angeles streets was not just a test of the city’s ability to embrace a car-free existence for a few hours. It also was a test of Metro’s ability to cope with the largest congregation of bicycle commuters it’s ever faced, as thousands turned to public transportation to get them to and from the 7.5 mile route.

And—while it’s certain that many riders encountered delays, crowded train cars or both—it’s clear that the event was a milestone in the agency’s evolving track record of accommodating bicycles aboard its subway and light rail trains.

“I think it was a great opportunity to show that bikes and commuters and trains can all coexist,” said Andres Di Zitti, a Metro transportation planner who took part in the event as a volunteer and photographed some of the action. “This year, there were many more people and we were able to respond quickly…As we got to downtown, and saw the big turnout and the platforms starting to fill up, we called the operations managers and they sent longer trains out. It was definitely a good learning experience for us.”

Bruce Shelburne, a director in Metro operations, was on the receiving end of many of those phone calls. His staff was able to respond by quickly adding extra cars to trains on the Red, Purple and Gold lines—doubling capacity in some cases. They also had a couple of standby trains available, and those were pressed into service as well.

“We handled a pretty stressful day,” Shelburne said. “There’s no transit agency in the world that could have processed the amount of bikes that we had out there, period. I haven’t heard any complaints yet. I’m sure we’ll get some. But overall, it was a positive experience.”

Joe Linton, a longtime bike activist and one of CicLAvia’s organizers, said Metro did a good job of making more room for cyclists on its trains during the event. “I heard that some trains were very crowded—which is a good problem to have,” Linton said.

Sunday’s CicLAvia was the city’s second, and two more are in the works, tentatively scheduled for July 10 and October 9. Both will follow the same basic route, although a “spur” to the USC/Exposition Park area may be added, along with a Chinatown segment.

At the same time, Metro is considering plans to open up its trains for more bike commuters every day—not just CicLAvia Sundays.

Bikes currently are banned from Metro trains during peak commuting hours. That could change under a proposal set to go before Metro’s Operations Committee on April 21. The committee also will consider whether to spend $950,000 to remove some seats from light rail cars to make more room for bicycles. Seats already have been removed from Metro subway cars, Shelburne said.

Carving out more room for bikes and other items onboard the trains is a testament to changing commuting habits. “Back in 1990, the biggest thing we ever saw on a train was a briefcase,” Shelburne said. “Now everybody takes their life’s belongings with them.”

Accommodating cyclists by allowing them to ride the trains anytime could carry more than just symbolic value, according to a staff report urging reversal of the peak-hour ban.

“Elimination of time restrictions would allow unfettered access to the rail system,” the report said. “This would encourage more people to ride transit knowing that they would be allowed to begin and end their trips using bicycles; reduce their carbon footprints as more cars come off the road and increase MTA ridership leading to a more sustainable environment.”

Although CicLAvia was a special event, it offered insights into how bikes and trains can coexist better day in and day out, Shelburne said.

“Every time we do this event, we find some things that were done wrong,” Shelburne said. A biggie: “Passengers need to understand they cannot block doors on the trains. We have to probably provide a little more education.”

Check for the latest closure information

Check for the latest closure information