Spotlight Story

The last map standing

September 28, 2011

After weeks of robust debate that sparked thousands of letters, e-mails and public comments, Los Angeles County’s most contentious redistricting process in a generation came to a dramatic close Tuesday as supervisors voted 4-1 to approve new political boundaries that hew relatively closely to the current map.

After weeks of robust debate that sparked thousands of letters, e-mails and public comments, Los Angeles County’s most contentious redistricting process in a generation came to a dramatic close Tuesday as supervisors voted 4-1 to approve new political boundaries that hew relatively closely to the current map.

The supervisors voted after hearing six hours of public testimony from 243 speakers who invoked the history of Latinos in L.A., the meaning of changing demographics and sharply divergent opinions on whether “racially polarized voting” still exists in the county to such an extent that it denies Latinos an equal opportunity to elect a person of their choosing. Others asked supervisors to preserve existing “communities of interest” so that neighborhood priorities such as protecting the environment and building health care networks would not be jeopardized.

In approving the redistricting map known as A3, supervisors rejected competing proposals by Supervisors Gloria Molina and Mark Ridley-Thomas that had sought to create a second supervisorial district in which Latinos make up a majority of the citizen voting age population.

In an initial round of voting toward the end of Tuesday’s meeting, it became clear that none of the proposed maps would receive the 4-1 “supermajority” vote needed to pass. So, after a brief closed session and some minor amendments to the A3 plan offered by Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich, Ridley-Thomas signaled he would change his vote.

“There is a rather obvious lack of consensus on a map here today,” Ridley-Thomas said. With a possible legal challenge from the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund looming, he said he wanted to avoid a “potentially divisive delay” and to push the matter toward the “closure” of a federal court ruling on what the Voting Rights Act required.

While he said he still believed in the plans he and Molina had put forward, he said he wanted to avert “the unnecessary gamble of the uncertainty of an untested appeal process”—a reference to the special redistricting commission made up of the District Attorney, Assessor and Sheriff that would have stepped in to decide the matter if the five-member Board of Supervisors had been unable to muster four votes for any of the proposals. After Ridley-Thomas’ change of course, the board voted 4-1 in favor of the A3 plan, with Molina casting the dissenting vote.

Ridley-Thomas’ S2 map and Molina’s T1 proposal would have moved up to 3.5 million residents to new electoral homes and split the San Fernando Valley into three supervisorial districts instead of the current two. The plans drew strong reactions across the county, and were criticized as blatant gerrymandering by Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky and others.

Knabe, in remarks before the vote, said that his A3 plan was the best way to ensure all groups in the county are well-represented. More radical boundary changes, he said, weren’t legally necessary and don’t reflect modern-day electoral realities.

“We cannot hold onto the past when we see clear illustrations of change with the election of minority candidates at every level of government,” Knabe said. “Hanging onto the legal battles of 20 years ago does nothing to move us forward…At the end of the day our job, as elected officials, is to represent all ethnicities, all people in Los Angeles County.”

Molina, however, in a presentation before the vote, contended that creating a second “meaningful Latino opportunity district” was required under the federal Voting Rights Act because of current demographics and a long history of bias.

“The legacy of Latino political exclusion and discrimination in L.A. County is so pervasive,” she said, “that it has affected not only the way Latinos and Latino candidates are perceived by non-Latinos but the way Latinos perceive their own ability to participate in the political process.”

Map A3, she said, waters down the voting strength of Latinos by creating a large Latino majority only in her 1st District while keeping their numbers to a third, or lower, in the other four districts. Latinos make up nearly 48% of the population countywide, and about a third of the county’s citizens of voting age.

Yaroslavsky kept his remarks brief, saying he had already written or said just about everything he needed to on the issue. But he thanked the community for what he called “this unprecedented turnout” and for the level of discourse throughout the process. “On the whole it was an elevated public testimony that we heard and it contributed to the public understanding … of what’s before us,” he said.

More than 900 people turned out for the meeting, arriving in the early morning, filling the board hearing room and spilling into three overflow rooms and a large white tent erected on the Hall of Administration lawn.

But by the time the final vote was taken just after 6 p.m., only a handful of spectators remained to witness the moment—the culmination of the once-every-decade process in which boundaries are redrawn to reflect U.S. Census data. (Click here for our story on the day-long civics lesson for hundreds of students who attended the meeting.)

The new district boundaries take effect in 30 days. Here are some of the changes in store forLos Angeles County under the plan:

More than 277,000 people will move to new districts, and several communities will get a new supervisor. Claremont, for instance, will move from the 5th District to the 1st. Santa Fe Springs will move from the 1st to the 4th.

Several other communities, now split between two supervisors, will be consolidated. The lake area of Silverlake will no longer be in the 3rd District, for instance; instead, the whole community will be drawn into the 1st District, as will all of Pico Rivera, Azusa and West Covina. Similarly, the 2nd District will encompass all of Hawthorne and all of Florence/Firestone, and the 4th District will include all of South Whittier and West Whittier/Nietos.

The San Fernando Valley will continue to make up more than 50% of the 3rd District’s electorate, and the 3rd District also will continue to represent the Westside, Hollywood and the Santa Monica Mountains. The 3rd District will lose 15,468 people, creating a district that is 45.8% white, 37.9% Latino, 11.1% Asian/Pacific Islander and 4% African American.

The population of voting-aged Latino citizens will fall in the 1st District from 63.3% of the electorate to 59.7%. In the 4th District, it will rise slightly from 31.6% of the electorate to 32.8%.

Asian Pacific Islanders, who had expressed concerns that redistricting would dilute their representation, will continue to be concentrated in the 1st, 4th and 5th Districts, with the highest concentration of voting-aged API citizens in the 1st District at 19%.

Population also will be more evenly distributed among the districts under the plan adopted Tuesday. Prior to A3’s approval, the largest district, the 5th, had 2,088,786 people, while the smallest, the 1st, had 1,893,001. That deviation, about 10%, will be reduced under the new plan to 1.57%.

Posted 9/27/11

It’s officially “Pacific Standard Time”

September 26, 2011

Pacific Standard Time starts this week in earnest, examining L.A.’s role in the postwar arts scene in venues as vaunted as the Getty Center and as modest as a Westside school for the arts.

Pacific Standard Time starts this week in earnest, examining L.A.’s role in the postwar arts scene in venues as vaunted as the Getty Center and as modest as a Westside school for the arts.

Although choice sneak previews have been open for a few weeks at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and at smaller museums, this weekend marks the official opening of the massive arts initiative centered on Southern California. Whether you love art or just love L.A., the range of shows opening this week should, like the city itself, have a little something for everyone.

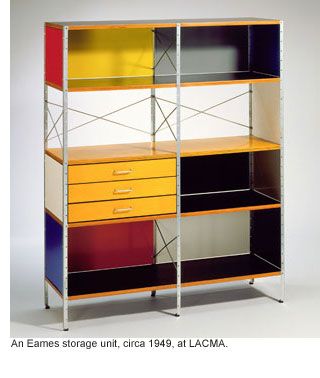

Highlights include the first major study of modern California design at LACMA, with an accompanying side exhibition at the A+D Architecture and Design Museum honing in on the work and philosophy of Charles and Ray Eames. The LACMA show, California Design, 1930-1965: “Living in a Modern Way,” will start with the origins of California modernism in the 1930s and include, along with important work by Richard Neutra and Rudolph Schindler, a vintage Airstream Clipper and a reconstruction of the Eames’ living room, which was dismantled piece by piece and moved to the museum from the Eames House in Pacific Palisades.

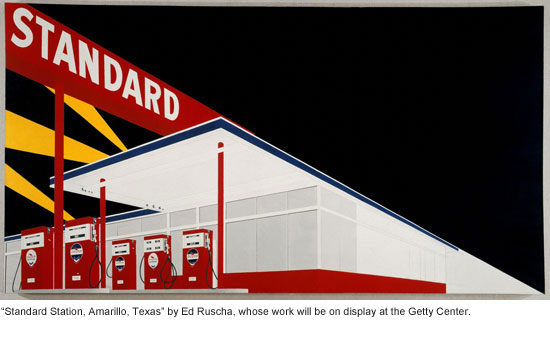

Another must-see show will be at the Getty Center, where Pacific Standard Time: Crosscurrents in L.A. Paintings and Sculpture will look at those two art forms in Southern California from the 1940s until the 1970s. The exhibition, featuring some 50 important L.A. artists, is in some ways the ground zero for the Pacific Standard Time initiative, which was launched as a joint initiative of the Getty Research Institute and the Getty Foundation.

The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles will also be in on the PST action, with a show that highlights its role as the city’s contemporary art venue before its art exhibitions were moved to LACMA in the mid-1960s. Among the featured artists will be John Baldessari, Ed Moses, Robert Irwin and Ed Ruscha.

The Hammer Museum will examine L.A.’s African American visual artists, ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives will look at the gay and lesbian art scene here and a show at MOCA’s Geffen Contemporary will show how L.A. art reflected the foment of the Vietnam War and the Watergate Era.

Meanwhile, a small show at the Sam Francis Gallery at the Crossroads School will explore the role of women art dealers in L.A. in the 1960s and 1970s.

And that’s only a taste of PST’s opening week of shows, talks and happenings. For a more complete calendar, click here, and for information on the initiative, click here.

Posted 9/26/11

Fighting fire with some super friends

September 25, 2011

Michel Proulx has spent so many autumns in Los Angeles that he’s now a regular at pickup hockey games in the San Fernando Valley. Stéphane Monette has used his off-hours to teach himself to speak Spanish and to surf. One year, it was so dry for so long that Christmas came and went before Carl Villeneuve could return to his wife and three children near Quebec City.

Michel Proulx has spent so many autumns in Los Angeles that he’s now a regular at pickup hockey games in the San Fernando Valley. Stéphane Monette has used his off-hours to teach himself to speak Spanish and to surf. One year, it was so dry for so long that Christmas came and went before Carl Villeneuve could return to his wife and three children near Quebec City.

“It was OK,” he recalls with a laugh in his French-accented English. “You do not have snow in Los Angeles, but you have a lot of the winter decoration. One time in each four or five years, it is not so bad.”

For the past 18 years, an elite band of French-Canadian pilots and mechanics has left the Quebec backcountry to spend their autumns—and occasionally their winters—fighting fires in Los Angeles.

Fresh from their own wildfire season, they board two Bombardier CL-415 Super Scoopers leased from the government of Quebec by Los Angeles County. In the bright fixed-wing aircraft, which fly much lower and slower than commercial jet planes, they make the long trip south and west to the land of sunshine, celebrities and Santa Anas.

Once here, they check into the Burbank Holiday Inn—”our Hollywood house,” as Proulx jokingly calls it. Some meet wives and children. Some unpack sports equipment. Some pull out fiddles and guitars and hold Acadian jam sessions in their hotel rooms.

Then they get down to some of the most dangerous work on either side of the nation’s northern border.

“It’s really a unique situation, ” says Battalion Chief Anthony Marrone, who for the past seven years has acted as the Los Angeles County Fire Department’s liaison with the fliers from Canada’s Service Aérien Gouvernemental.

“They come here to risk their lives for people they don’t know, for a place that isn’t their country, for a job in which they’re not making a ton of money. But over the years, they’ve really become a part of our firefighting family.”

The famed Super Scoopers, which over the years have become a red-and-yellow icon of Southern California’s fire season, skim water from local lakes and the ocean and airdrop it onto wildfires. Los Angeles County has leased two of the sturdy aircraft during fire season annually since 1994, a year after the Old Topanga Fire killed three people and destroyed hundreds of homes in Topanga, Malibu and Calabasas. Each plane can pull in 1,620 gallons in 12 seconds, dump it and circle back at more than 170 miles an hour.

Marrone says the Super Scoopers cost the county about $2.75 million each fire season, which typically runs for 90 to 120 days, from September into December.

That price includes the pilots and their support crews, who work in 11-man rotations—four captains, four copilots and three mechanics. Each group stays for about a month, working out of the county’s air tanker base at the Van Nuys Airport, before a new group arrives via commercial airlines.

Over the years, the crews have been summoned to nearly every major fire in the county, particularly since the devastating 2009 Station Fire, when the U.S. Forest Service, which was managing the blaze, was criticized for not deploying more air power. The fire, the largest in county history, claimed the lives of two Los Angeles County firefighters while burning more than 160,000 acres and destroying some 200 homes and other buildings.

Since their arrival September 1, the planes and their crews have helped extinguish blazes in Newhall, Agua Dulce and Mandeville Canyon, among other hotspots.

“They’ve been there in Malibu, in the Buckweed Fire in Santa Clarita, in La Cañada Flintridge, in Diamond Bar and Palos Verdes, in Calabasas—everywhere,” says Marrone. “I was the helicopter coordinator on the Marek Fire in 2008 and they were out there long after any other air tanker would have had to turn back.”

The pilots downplay the danger.

“Sometimes we get bounced around when the Santa Ana winds pick up and we’re in the canyons, but mostly it is business as usual,” says Proulx, 46, who has been coming to L.A. since 2001. “We fly an aircraft that performs well in that kind of situation. When you’re using the right tool, it’s like driving a rig—it’s just a job.”

“We manage the risk carefully,” agrees chief pilot Villeneuve, who spent 11 years as a Canadian bush pilot before signing on with the Service Aérien Gouvernemental 15 years ago.

The biggest challenge, they say, is to keep track of all the moving parts of an urban fire scene. The wilderness of Quebec has its pitfalls, but news choppers and power lines and dolphins leaping in and out of the waves don’t tend to be among them. Nor do subdivisions and milling crowds.

The biggest challenge, they say, is to keep track of all the moving parts of an urban fire scene. The wilderness of Quebec has its pitfalls, but news choppers and power lines and dolphins leaping in and out of the waves don’t tend to be among them. Nor do subdivisions and milling crowds.

In Canada, Proulx says, their work mostly involves dipping into remote lakes to put out forest fires. But L.A. “looks like Legoland from the sky—I don’t know the English word for it, but the city goes on and on forever and ever. When we drop the water, we’re about 75 to 100 feet above the ground and we can see the people waving and all that. Sometimes we can see the firefighters’ faces down there.”

In fact, Monette says, one of his most vivid experiences here was in 1999 during his first L.A. fire season, when he looked down from the cockpit and realized for the first time just how high the human stakes would be on this job.

“The fires were so close to the people and the cities—it made me feel that to miss just one drop would be awful,” remembers the veteran pilot. Now 46 and the father of two teenagers in Quebec City, Monette has volunteered for the Los Angeles County contract at least a dozen times since that initial flight.

For the Canadians, the L.A. rotation is more than just a chance to hone their job skills. It’s also an opportunity to create a traveling hybrid of north-south culture. Some, like avionics technician Jean Larocque, go mountain climbing in their off hours. Eric Tremblay, 45 and on his first stint here, went to Lake Arrowhead during some time off last weekend. Jean-David St.-Laurent, a 37-year-old serving his second year in L.A., says he has taken to starting each day with a brisk 2-hour hike through the chaparral in Wildwood Canyon Park, near the hotel.

Monette is drawn to the beaches when he manages to get a day off; over the years, he says, he has acquired two surfboards. He also has worked on his communication skills. “I was surprised when I came here that everything was more or less in Spanish, not English, so I learned the language,” he recalls.

Coming to California, he says, “was a dream, since I was a little boy—this place is so associated with freedom, the California way of life.” The reality is, of course, more complex, he has since decided. “How free are you, really,” he asks, “when your way of living turns out to be an eternal rush hour?”

Proulx, whose rotation starts in October, plans to find an amateur hockey game as soon as he gets here, a habit he developed after he hooked up with an organization for Quebec expatriates online. “This year, I’m thinking about Burbank—I’ve already played in Simi Valley and Van Nuys.”

And, he adds, he’ll be bringing his fiddle.

“Another guy brings his guitar, and sometimes in the evenings, we have a few beers and play music until the bursar from the hotel comes and tells us to lower the noise.

“We play funny songs, dirty songs…My favorite one is called in English, ‘You’ve Broken the Chain on my Tractor.’ Hey, you got to do something besides just wait for fires.”

But the best part of coming to L.A., they say, is the chance to be of assistance.

Each year, they are touched by the grateful fan mail they receive. Once, they were feted by Topanga homeowners; another time, a classroom of schoolchildren drew them a packet of pictures.

And the Canadians have a secret: L.A. brushfires die more readily than Quebec’s tree-fueled conflagrations, especially with fire operations as well-run as those here.

“In Canada, we can be working on a fire for days and days and you can almost never see the end of it,” Proulx says. “But in L.A., you take off and see that big smoke, and every time, we know we’re going to go work hard and fight hard, but we got a good chance to win.”

Posted 9/14/11

A surf story for the ages—all ages

September 8, 2011

Just imagine the sand that’d be flying these days if a band of wild, salty teenagers turned a 9-bedroom mansion in the exclusive Malibu Colony into their flophouse, lazily draping themselves across a couch they’d hauled out front or dropping a new engine into their Woodie for the whole neighborhood to see and hear.

Just imagine the sand that’d be flying these days if a band of wild, salty teenagers turned a 9-bedroom mansion in the exclusive Malibu Colony into their flophouse, lazily draping themselves across a couch they’d hauled out front or dropping a new engine into their Woodie for the whole neighborhood to see and hear.

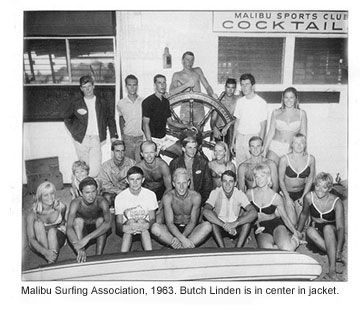

Back then, they were too young to know—or to even give a hoot—that they were creating a culture that would come to define Southern California in the ‘60s and beyond. These were the real beach boys and girls, mastering one of the world’s best surf breaks during the sport’s breakout years. They were the young, the proud, the hard-partying members of the Malibu Surfing Association.

This weekend, the association will once again be hosting its annual MSA Classic, bringing together the best surf clubs in the world to compete at Malibu’s legendary “First Point” at Surfrider Beach. But this time, expect a few more graybeards in the lineup and on the shoreline.

This year’s contest commemorates the 50th anniversary of the Malibu Surfing Association, a multi-generational stretch that has seen the sport explode into a multibillion dollar industry. In addition to hosting contests, the MSA prides itself on its active involvement with a variety of environmental issues impacting the water and beach of Surfrider. According to MSA President Michael Blum, the group’s invitation-only membership ranges in age from 8 (“he’s still on the learning end of surfing”) to 80 (he sometimes has some trouble getting his waves”).

“What it all comes down to,” Blum says of the club’s mission “is that we have Malibu in our name, and that beach means a tremendous amount to us.”

Among the many current and former members who’ll be on hand this weekend is Butch Linden, one of the MSA’s eight founders and its first president. It was Linden’s home in the Colony where young surfers from here and abroad would drop by, sometimes staying for months.

“My mom loved kids,” says Linden, now 68 and still surfing. “They were going to get breakfast, lunch, dinner, whatever.”

Linden, one of the first to tackle the treacherous Pipeline on Oahu’s North Shore, says that when the group was formed in November, 1961, surf clubs from San Diego to Santa Cruz were competing against each other. Linden and his highly skilled pals figured they could take on all comers. “We were the extreme kids,” he says.

Two years after its founding, the MSA held its first invitational at Surfrider, where the land was still owned by the Rindge-Adamson family, owner of Adohr Farms, one of the country’s largest dairies. Concerned about liability and looking for a way to dissuade the young surfers, the family said the boys would first have to obtain a $1 million insurance policy from Lloyds of London. With the help of an adult sponsor, Linden says, “we pulled it off.”

Before long, dozens of kids were flocking to the club’s weekly gatherings at the Malibu Inn. “We met every single Tuesday for eight years,” says Linden. (Now it’s once a month.) The membership included teenagers from a few famous neighborhood families, including the Hilton brothers. “We had so much fun. We had parties all the time. It was really something.”

Surf clubs, of course, aren’t for everyone. The sport is highly individualistic, with most of the accomplished surfers—and even those who are not so accomplished—always working to position themselves for the maximum number of waves during a session. That’s particularly true at Surfrider.

“You have to be ready for it. You have to have your mindset ready to battle the crowds out there,” says MSA member Julie Cox, who prefers the mellower scene at Leo Carrillo, north of Surfrider.

Cox says she grew up in team sports, playing high school basketball in Agoura Hills. So joining the MSA in 1996 at the age of 16 to surf competitively seemed a natural fit.

“It helped push my surfing level forward,” says Cox, 31, operations manager of the California Surf Museum in Oceanside. “And you get really stoked if another Malibu girl makes it through her heat. You get to root for your friends.”

This weekend, Cox will be competing in both shortboard and longboard events. But it’s the bigger board, with its smooth glide and lineage to the past, that she and the MSA favor. “It suits my personality,” says the graceful surfer. “A little more laid back.”

Cox says she wouldn’t miss the contest.

“I know how hard the club has worked on this. You can’t go wrong with September at the beach in Malibu. The waves are beautiful, the water temperature is warm and most of the crowds have gone home. It’ll be a great reunion.”

Surfer Gary Sellern says he’ll be in the water, too—shoulder be damned. It’s bone-on-bone, he says, the result of “surfing insanely for 50 years.” Sellern, now 77 and a former MSA president, says his physical problems have kept him largely dry-docked for more than a year. “My wife is almost kicking me out of the house,” he says. “The club and surfing, that’s been my life for half a century.”

This weekend, however, Sellern is lugging a huge 11-foot board that will take less paddling strength to build speed in the water, hopefully allowing him to catch more waves. But even during these frustrating months out of the surf, he says, the camaraderie and support of the MSA has helped him flow with his advancing years.

Without it, he says, “I’d go crazy.”

Posted 9/8/11

Get a jump on “Pacific Standard Time”

August 31, 2011

It’s going to be a big, big autumn for art in Los Angeles. In fact, a few places are already offering a sneak peak at the season’s most massive undertaking—“Pacific Standard Time.”

It’s going to be a big, big autumn for art in Los Angeles. In fact, a few places are already offering a sneak peak at the season’s most massive undertaking—“Pacific Standard Time.”

More than 60 cultural institutions and 60 galleries across Southern California will be joining forces in coming weeks to jointly tell the story of L.A.’s rise on the post-World War II art scene. The collaboration—its full name is “Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945-1980”—will offer an unprecedented panorama of West Coast art and design.

The initiative was launched about ten years ago after local curators and artists became concerned that important L.A. work was not being appropriately preserved and archived.

“Many of the key figures were getting up in years, [and] their papers were being dispersed,” says Andrew Perchuk, deputy director of the Getty Research Institute. With nearly $10 million in grants from the Getty Foundation, a plan was launched to not only recapture an era, but also share its back story.

What emerged was the mother of all group shows.

“Initially, we thought there would be four or five related exhibitions, but then it just started snowballing,” says Rani Singh, co-curator of the Getty Center’s own exhibition, “Pacific Standard Time: Crosscurrents in LA Painting and Sculpture, 1950-1970,” which opens October 1.

That’s the official kickoff date for the “Pacific Standard Time” extravaganza, whose highpoints will include exhibitions featuring such greats as Ed Ruscha, Lita Albuquerque, Betye Saar, Henry Takemoto, David Hockney and Judy Chicago, as well as the first major study of California midcentury modern design.

Unofficially, however, dozens of exhibitions are scheduled to open early, with several key shows welcoming the public as soon as this week.

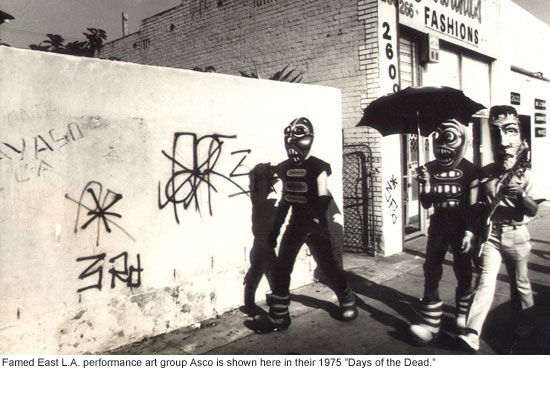

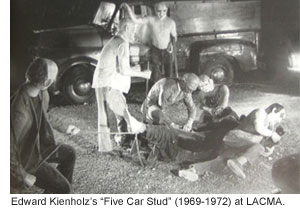

Among them: the first public showing in the United States of Edward Kienholz’s “Five Car Stud (1969-72),” and the first retrospective of the work of the legendary East L.A. underground arts collective, Asco.

Both of those exhibitions open Sunday, September 4, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, under the Pacific Standard Time banner. But LACMA is just one of many places offering a first taste of L.A.’s incoming autumn of art.

Here’s an early “Pacific Standard Time” sampler for this weekend:

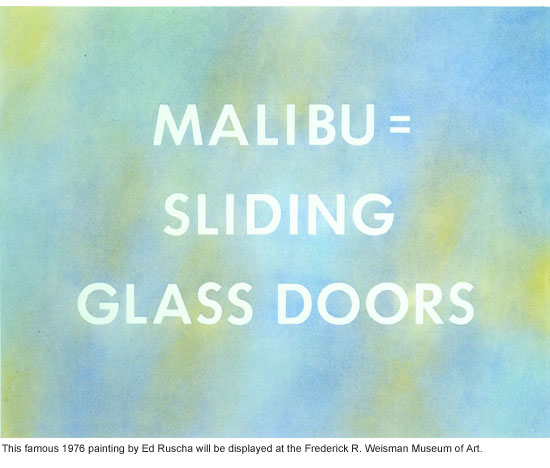

- “California Art: Selections from the Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation” has been open

since August 27 at the Frederick R. Weisman Museum of Art near the Malibu campus of Pepperdine University. Weisman was an early patron and friend of L.A. artists and his collection features such now-renowned names as Ed Ruscha and Robert Irwin. The show features pieces by those artists and others whose work went on to become almost synonymous with art in L.A .

since August 27 at the Frederick R. Weisman Museum of Art near the Malibu campus of Pepperdine University. Weisman was an early patron and friend of L.A. artists and his collection features such now-renowned names as Ed Ruscha and Robert Irwin. The show features pieces by those artists and others whose work went on to become almost synonymous with art in L.A .

- “It Happened at Pomona: Art at the Edge of Los Angeles, 1969-1973, Part 1: Hal Glicksman at Pomona.” This show, at the Claremont liberal arts college that produced Chris Burden, has been open since August 30 at the Pomona College Museum of Art. Glicksman was a pioneering curator during the late 1960s and early 1970s, and his guidance shaped a generation of L.A. artists. The first of three “Pacific Standard Time” exhibitions at the museum, the Glicksman show features such important artists as Judy Chicago, Michael Asher and Lewis Baltz.

- Edward Kienholz’s “Five Car Stud (1969–72)” was among the artist’s last works in Los Angeles before he left to live between Idaho and

Berlin. It remains one of his most disturbing pieces to this day. A devastating tableau in a darkened room around a dirt patch, it depicts a black man being pinned down in a circle of headlights and castrated by white attackers while a white woman vomits in his pickup. Acquired by a Japanese collector shortly after a its only public showing (in Europe), it remained in storage until 2007, when it was sent for restoration to Kienholz’ widow, artist Nancy Reddin Kienholz. Its September 4 opening at LACMA, 17 years after Kienholz’ death, will mark the piece’s American public debut.

Berlin. It remains one of his most disturbing pieces to this day. A devastating tableau in a darkened room around a dirt patch, it depicts a black man being pinned down in a circle of headlights and castrated by white attackers while a white woman vomits in his pickup. Acquired by a Japanese collector shortly after a its only public showing (in Europe), it remained in storage until 2007, when it was sent for restoration to Kienholz’ widow, artist Nancy Reddin Kienholz. Its September 4 opening at LACMA, 17 years after Kienholz’ death, will mark the piece’s American public debut.

- “Asco: Elite of the Obscure, A Retrospective, 1972–1987 “ is the first retrospective of a L.A.’s seminal 1970s Chicano arts collective, now individually famous as Gronk, Harry Gamboa, Jr., Willie Herrón and Patssi Valdez. Inspired by influences that ranged from the Chicano rights movement to Dada, the four spent several years inciting happenings and doing performance art on the streets of East L.A., making themselves legendary in the city’s avant-garde underground long before anyone heard of guerrilla art or flash mobs. (Click here for a video of the L.A. artist Gronk recalling Asco’s style and history.) Today, a generation of young L.A. artists credit them as an influence.

- “Maria Nordman, Filmroom: Smoke, 1967–Present” is also opening September 4 at LACMA. Light—particularly the light in L.A.—is one of the great recurring themes in the “Pacific Standard Time” shows. Nordman began making her light-filled films and installations in the mid-1960s; this film was made in 1967 without a script on a beach in Malibu. It features two actors, but the sun and the Pacific Ocean are co-stars, the artist has said.

Posted 8/31/11

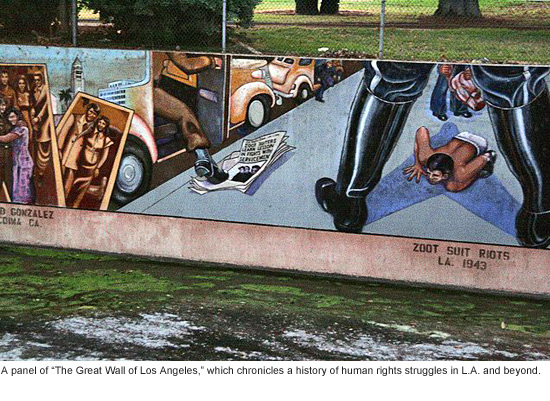

A “Great Wall” becomes even greater

August 30, 2011

Every city has its hidden treasures. Take “The Great Wall of Los Angeles”.

Every city has its hidden treasures. Take “The Great Wall of Los Angeles”.

More than three decades old and 13 feet high, it unfurls like a vibrant tattoo for nearly a half-mile, recounting the history of human struggle and achievement along a concrete retaining wall in the Tujunga Flood Control Channel.

Flanked by a narrow park, it’s easy to miss what’s believed to be the longest mural on the planet. And yet it is this singular work—painted by hundreds of hands in the course of five summers—that launched Los Angeles’ reputation as the world’s mural capital.

Despite such rich origins, few public artworks have had to endure so many indignities. It’s been soiled by car exhaust, corroded by smog, bleached by fertilizer runoff and baked by the relentless sun of the San Fernando Valley. What’s more, political crosscurrents over the decades have generally put the kibosh on obvious possibilities for expanding the project, even as its once radical-seeming material—from the sins of the Spanish missionaries to the Japanese internment—has crossed into the historical mainstream.

“One would think it would have completely disappeared by now, given all it’s gone through,” marvels Judy Baca, the Watts-born activist, artist and UCLA professor whose vision has, since 1976, been the guiding light behind the project. “But what’s remarkable is how much of it is still there.”

Los Angeles has more than 3,000 murals, and their upkeep has been an ongoing civic battle. But next month will bring good news from “The Great Wall.”

For the past three years, Baca and a crew of artists, volunteers and interns have been painstakingly restoring the artwork. In mid-September, the project is expected to be finished. A ribbon-cutting and celebration are being planned for September 17 at the park near the wall, which lies between Burbank Boulevard and Oxnard Street off Coldwater Canyon Avenue. (Click here for driving directions.)

For the past three years, Baca and a crew of artists, volunteers and interns have been painstakingly restoring the artwork. In mid-September, the project is expected to be finished. A ribbon-cutting and celebration are being planned for September 17 at the park near the wall, which lies between Burbank Boulevard and Oxnard Street off Coldwater Canyon Avenue. (Click here for driving directions.)

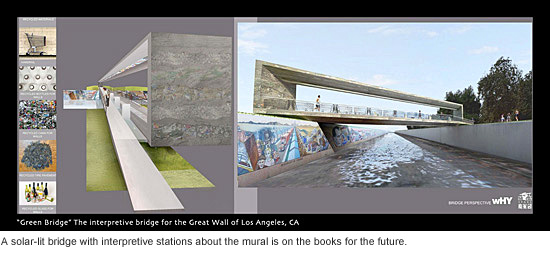

After that, Baca says, signage, lighting and a solar-lit “green” bridge with interpretive stations will be added, the better to see and understand the monument to L.A.’s multi-cultural history.

The entire $2.1 million improvement—spearheaded by the Venice-based Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC), with funding and assistance from the City of Los Angeles, L.A. County, the California Cultural and Historical Endowment, the Rockefeller and Ford foundations, the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy, Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s office, and others—should be finished late next year.

That, in turn, will set the stage for a fundraising drive to finish the next four decades of the mural (it now stops in the 1950s) using already-designed sketches that will take the narrative through the Vietnam War and the Los Angeles riots up to the 21st century.

For Baca, now an iconic figure on the Los Angeles art scene, the restoration is both a personal and civic milestone. A one-time high school art teacher in the San Fernando Valley, she has spent the better part of her life as a fiery advocate for public art.

As a summer art teacher in 1970 for the City of Los Angeles, she organized rival gang members in East Los Angeles to paint “Mi Abuelita,” a mural of a grandmother with outstretched arms that for many years was a Hollenbeck Park landmark. The project landed Baca a job as the head of a citywide mural program manned by at-risk teenagers, and led from there to the creation of SPARC, the nonprofit community arts organization.

“The Great Wall,” commissioned by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers at the behest of the L.A. County Flood Control District to help improve the area around the Tujunga Wash, was SPARC’s first project. Since then, SPARC, for which Baca is artistic director, has produced hundreds of murals throughout the city, commissioning hundreds of artists and training thousands of youth apprentices.

More than 400 at-risk youths, along with scores of artists and historians and hundreds of community members, worked on “The Great Wall” between 1976 and 1984, when painting stopped due to rising costs and safety concerns and the changing political climate during the Reagan Era. Many of those who worked on it found the experience to be life-altering, as this video recounts.

Although the mural’s initial segments were designed by at least 10 artists, each taking a different historical period, it was Baca who created the overall aesthetic beginning with the 1920s mural panel. When the “Great Wall” was started, she was 30. By the time she and her crews celebrate its restoration, she’ll be a week shy of 65. Time, she laughs, has taken a toll on the artist as well as the art.

“We have a funny thing going on down there,” she says of the restoration. “We have the senior citizens, who aren’t body-agile but have great hands, and then we have the younger ones, whose hands aren’t as adept but who have the bodies to continue. We’re transferring knowledge and teaching them to collaborate—it’s a very important moment.”

But, she adds: “I think this will be my last year on the channel. It’s incredibly physically demanding. I think it’s time for the younger people to take over.”

Meanwhile, she says, she’s had the privilege of revisiting a formative period in her life.

“I’m having these dialogues with my younger self on a daily basis,” she says. Simple decisions—what color to use in restoring the image of an Okie, or whether to underscore the Madonna-and-child subtext of a migrant worker holding a baby—“give me this visual of who I was when I painted it,” Baca says.

“That Judy was working with this incredible passion. She had boundless energy and this incredible willingness to put it all out there. This Judy, at 65, would probably say, ‘This is way too hard.’”

If she had to do it all over again, she says wouldn’t change a thing.

Although the project, in retrospect, was an “incredible marathon” and a massive undertaking, she says, it also was “a great labor of love”—and of youthful idealism.

“I may have much more wisdom now, but that girl was limitless,” says Baca. “She was limitless.”

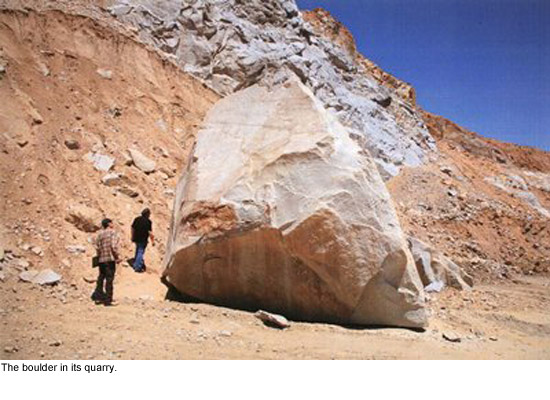

“The Rock” set to roll through L.A.

August 15, 2011

Later this summer, a 340-ton boulder will make its way from the Inland Empire to the middle of Los Angeles.

Recumbent on steel beams and a specialized 208-wheeled transporter, it will travel by night as the basin lies sleeping, a rough mass of California granite 21 feet wide and two stories tall. It will move on surface streets because it is too slow and huge for the freeway. At each dawn, it will halt; its entire 72-mile trip will take place at less than 10 mph.

From one end of the Southland to the other it will make its epic 9-day journey: down dark frontage roads beside the Pomona Freeway, past the twinkling lights of Ontario International Airport, along strip-malled boulevards in Diamond Bar and Walnut, through porch-lit subdivisions in Whittier and La Palma. Preliminary route maps take it past fast food joints in Compton, startling the night shift, and up through South L.A. by starlight, taking in the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum and the stately palms of the West Adams District.

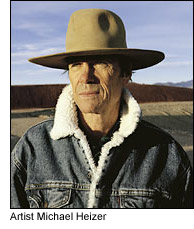

Finally, The Rock, as its guardians have come to call it, will turn on Wilshire Boulevard, lit by the city and flanked by office buildings, and jog north on Fairfax Avenue for just a short distance. There, at last, it will find its elegant new setting—poised over a 456-foot-long, 15-foot-deep concrete trench as part of Michael Heizer’s Levitated/Slot Mass, an internationally anticipated installation at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

“It’s not like anything we’ve ever done,” says LACMA’s associate vice president for special art installation, John Bowsher, who is overseeing the boulder’s odyssey.

The artwork, scheduled to open to the public in November, will allow visitors to walk underneath the massive granite formation, down a slope that will create the illusion that the boulder is levitating. Assembled, the piece will be about as tall as the Resnick Pavilion, its neighbor on the LACMA campus.

But if Heizer’s work is expected to be a tour de force, so is its installation. LACMA director Michael Govan has called The Rock “one of the largest monolithic objects moved since ancient times.”

Orchestrating the rock’s move to LACMA from a Glen Avon quarry will be Emmert International, a Portland, Ore.,-based heavy-haul transporter.

Although Emmert and LACMA officials declined to discuss costs, officials at the quarry say they have been told the move, including fees, prep work and transport, will cost about $1.5 million. Emmert’s director of operations, Mark Albrecht, says the company’s fee is considerably less than that figure. The transport, like the artwork, is being financed with private donations.

Although Emmert and LACMA officials declined to discuss costs, officials at the quarry say they have been told the move, including fees, prep work and transport, will cost about $1.5 million. Emmert’s director of operations, Mark Albrecht, says the company’s fee is considerably less than that figure. The transport, like the artwork, is being financed with private donations.

Albrecht says a 15-man crew will accompany the boulder throughout the journey, along with various LACMA officials and police escorts. Though a tentative route has been mapped out, he says, the company is still in the process of acquiring state and local permits.

So far, the boulder is expected to travel uncovered (“No plans to shrink-wrap it, or anything like that,” he says, laughing). But like the route and the planned August 5 departure date, that could change as the deadline approaches. LACMA’s Bowsher says there’s been talk of boxing or partially covering the boulder because the artist is concerned that the spectacle of a 21½-foot-high hunk of granite riding like the Rose Queen through the streets of Los Angeles County will detract from the totality of the sculpture.

Heizer, who is famously private, could not be reached for comment. But Albrecht says the artist “has been involved for the whole process,” cautioning them via LACMA to “make sure the rock isn’t scratched or etched, make sure it’s carefully handled, make sure you don’t leave any big marks on it.”

Damaging it would seem to be the least of anyone’s worries, considering that the boulder was blasted in 2005 from the face of a quarry in the Jurupa Mountains and survived intact.

“Came right from the crown of the mountain,” marveled Dan Johnston, then-project manager for Paul J. Hubbs Construction, which owned the quarry. “Blast brought it down and it landed right in the middle of soft dirt.”

Johnston, now retired, says that as soon as he saw it he called Heizer, a geologist’s grandson known for massively scaled artworks, including Double Negative, a 1,500-foot trench cut into the side of a desert mesa.

“Michael had bought some large rocks from us before, in 2004 and 2005, for other projects,” Johnston says. “He wanted granite, and the thing about granite is that not a whole lot of places have it. Riverside granite is like Portland cement—if you know about rock, it’s something you look for. And he had come to us looking for large rocks.

“Well, that was one good-lookin’ rock…Way it was shaped, I knew he’d love it. And he did, he fell in love.”

Stephen Vander Hart, co-owner of Stone Valley Materials Inc., which now owns the quarry, says he had heard that the artist paid $120,000 for the boulder. But Johnston, while refusing to divulge the actual price, says “it was nowhere near that much.”

Vander Hart says the quarry’s crews had been working around the rock for years when his company took over in 2010, and its safekeeping was a condition of the buyout.

“We’ve had to work hard to not bump into it,” he says. “Most of the guys here are just regular equipment operators, blue collar guys, love their wife and kids, and they’re just like, ‘Get it the hell outta here, let me do my job. They’re not that into art.”

But the quarry boss says he, for one, was touched when he heard LACMA Director Govan talk about the artwork and how it came to be.

“He talked about how 400 years from now, people would ask, ‘How did this group of people move something this size? What was their motivation?’ California is all strip malls and franchises. Everything is brand new, at least here in the Inland Empire. We bury our history. But this is something that will be there for a long, long time.”

Posted 6/29/11

Updated 8/16/11: The groundwork is taking a little bit longer than expected, but officials at LACMA say the rock is expected to roll shortly after Labor Day.

“There were some permitting issues for the route from the quarry, ” says Miranda Carroll, LACMA’s director of communications. The tentative start date now is September 6, with an arrival at the museum on September 14 or 15, she says.

The 340-ton boulder is a key element in a much-anticipated installation by the reclusive earth-art master Michael Heizer. Museum officials had hoped to move the 340-ton boulder from its Riverside-area quarry this month.

In any case, Carroll added, “there won’t be a big hoo-hah because we’ll be moving it in the middle of the night.”

Metro’s lost world

July 27, 2011

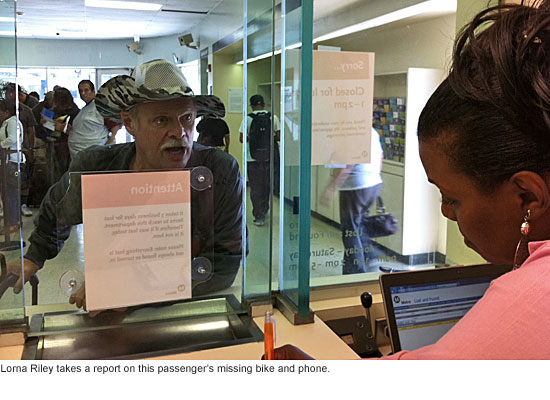

Forgetful transit riders, Lorna Riley has your back—and your backpack.

Forgetful transit riders, Lorna Riley has your back—and your backpack.

Also your keys, mobile phone, mountain bike, prescription medication, “Lilo and Stitch 2” DVD and quite possibly your dry cleaning.

Riley, the doyenne of Metro’s Lost and Found, has seen just about everything in her 13 years with the agency—including a human jawbone (part of a college science experiment), a district attorney’s gang file (quickly returned to its official owner) and a memory stick full of JPL data (ditto.)

“We get it all,” she says.

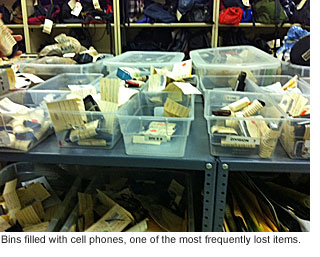

But this week, Riley’s encountering something that even she’s never seen before: a new computerized system in which a barcode is assigned to each of the thousands of items left aboard Metro trains and buses each year. The items are logged in a computer database, making quick scans for likely matches possible. And the traveling public can now submit online claim forms for missing items. A personal visit to the Lost and Found, located in Metro’s Wilshire/LaBrea Customer Center, is still required to pick up missing things, although Riley will mail items to out-of-towners.

“We’ve shipped stuff back to Australia,” she says. “Being L.A., we get a lot of tourists. France, China, Belize.” Not too long ago, a teenager from Georgia, in town for a Boy Scouts gathering, left his backpack on the bus—fully loaded with all his electronic devices. While he won’t be winning any merit badges for keeping track of his stuff in transit, he did remember to place a luggage tag on the pack, enabling Riley to track down his mom and reunite the scout with his wayward backpack.

Alan Gee, Metro’s manager of Customer Programs & Services, says he hopes the new system will make that kind of happy outcome more common. As it is, he estimates that up to 50% of bicycles and up to 30% of other items end up being claimed by their owners; he’d like to see that increase to 75% for bikes and 50% for other things. “We don’t want this stuff,” he says. “Come and get it, please!”

Alan Gee, Metro’s manager of Customer Programs & Services, says he hopes the new system will make that kind of happy outcome more common. As it is, he estimates that up to 50% of bicycles and up to 30% of other items end up being claimed by their owners; he’d like to see that increase to 75% for bikes and 50% for other things. “We don’t want this stuff,” he says. “Come and get it, please!”

Tucked away behind the scenes at the bustling Customer Service center, the Lost and Found is a crowded jumble of artifacts abandoned by a metropolis in motion.

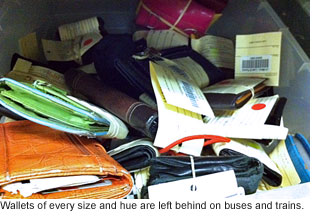

Wallets of every color and size are bundled together in a bin. Abandoned shopping bags are grouped according to where they were found. Guitars share shelf space with a forlorn carpet cleaner. An entire room is dedicated to bikes. Forgotten dry cleaning hangs on a garment rack in a hallway.

There are rolls of toilet paper, rolls of blueprints, a tube of toothpaste, a surprising number of crutches and seemingly enough backpacks and suitcases to rival baggage claim at LAX, or at least Burbank.

“Every time I come here, I’m just baffled,” Gee says. “I mean, really?”

The new database doesn’t have the same atmosphere as the Lost and Found itself—in a renovated Miracle Mile building that was once the setting for Tilfords Restaurant and Coffee Shop—but still manages to convey a sense of the varied lives passing through the transit system. Some recent entries: “alcoholics anonymous book and pen,” “1 black wallet with $3.00,” “red framed glasses.”

“We see the full spectrum,” says Riley, 54. “Due to the economy, I think more people are riding public transportation. We get a lot of people, from the homeless to the mayor’s office.”

While the new automated system is expected to make it easier to match up missing items with their owners, the human touch is still essential.

While the new automated system is expected to make it easier to match up missing items with their owners, the human touch is still essential.

Earlier this week, Riley, who previously worked in retail and ran her own party events/corporate gift business, patiently met with a steady parade of passengers who’d left something behind on the bus or train.

“We’ll keep a lookout for it,” she told one woman, who was seeking a red Ed Hardy hoodie she’d left on the bus from downtown to the beach. “Give it a couple more days, OK?”

The passenger had lost the pullover a few days ago, and held out scant hope of seeing it again. “I doubt it, but it’s worth a try,” she shrugged before leaving the window.

Sometimes the customers are more frustrated than resigned.

“They’re angry with themselves because they lost it,” Riley says. “Sometimes they’re so upset that it’s hard to tell what they’re looking for. I’m pretty good at calming people down.”

Riley prides herself on being able to find her way to the items she’s logged in using a color-coded system that she developed.

And she knows her repeat customers.

“I have one regular who loses his bike. He lost it three times in one month. He almost uses Metro as public storage.”

She’s even had father-daughter and father-son teams—in which both got off the bus and left their bikes behind.

Items not claimed after 90 days are auctioned off or donated to charity. Still, some things linger longer, like a Barbie tricycle, still in its bright pink box, that was left on a Blue Line train last December and is still waiting for someone (Santa Claus?) to pick it up and deliver to its rightful owner.

When she can, Riley plays gumshoe. “I have a little file that I call research,” she says. By tracking down leads and calling around, she’s been able to locate and return important documents, such as death certificates and burial permits, as well as objects of sentimental value, like wedding photos.

“Usually,” she says, “I go home with a good feeling because I’m helping people get their things back.”

Posted 7/27/11

Dinosaurs roar back to life at exhibit

July 7, 2011

Their body temperatures were almost the same as a human’s. Some had plumage and the ability to make noises. Some had footprints and tail shapes about which we were wrong until recently.

Their body temperatures were almost the same as a human’s. Some had plumage and the ability to make noises. Some had footprints and tail shapes about which we were wrong until recently.

We’re fairly sure about what killed them (fallout from a meteor crash) and what they evolved into. (Hint: It has feathers). But much of their 230 million years on the planet remains a mystery.

You could fill an encyclopedia with what scientists are still discovering about dinosaurs. But for the past several years, Luis Chiappe, director of the Dinosaur Institute at the Los Angeles County Natural History Museum, has had something even bigger in mind.

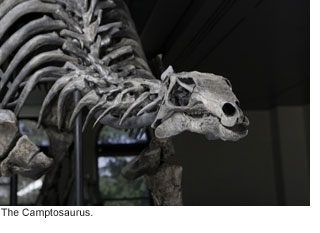

This month, a newly renovated, 14,000-square-foot Dinosaur Hall will open, doubling the dinosaur display space at the museum. The permanent exhibition, which opens to members July 10 and to the general public July 16, will feature some 20 new major mountings from the museum’s expanded collection—from an extraordinary trio of young Tyrannosaurus rex skeletons to the smallest dinosaur ever discovered in North America. It also will reflect the ways in which technology has revolutionized paleontological research.

“This is not a chronological journey through time, and this is not setting animals in dioramas,” says Chiappe, who led much of the fieldwork responsible for the exhibit and curated it as an invitation to visitors to regard the towering fossils with a scientific eye.

“This is, ‘How do we know what we know? How do we reconstruct the life and, in the end, the death of these animals?’ This is an up-to-date, state-of-the-art understanding of the lives of the dinosaurs.”

In other words, this is not your father’s dinosaur museum. The new Dinosaur Hall will fill two rooms with nearly 300 specimens collected over nearly a century, with at least a third of the major pieces never before having been shown to the general public.

Displays will include background on how technological advances such as CT scans and particle accelerators have, for example, helped scientists understand the internal organs of dinosaurs and deduce the original colors of their skin and feathers. Many of the pieces have yielded important new discoveries and resulted in published research.

“Some amazing things were unearthed in the course of doing this hall,” says John A. Long, vice president of research and collections at the museum, which operates not just as a showcase, but also as a major research institution.

And, Long adds, because of improvements in conservation methods, “you can see the bones better—they’re better prepared.”

Among the showpieces will be the dramatic grouping of young T. rex skeletons—baby, early adolescent and teenager—that, taken together, make up the world’s only depiction of the famous carnivore’s growth pattern.

Also featured will be one of the most anatomically accurate depictions to date of the massive Triceratops, culled from several finds that included a completely articulated set of front leg, or “arm”, bones—a rarity that has contributed a fresh understanding of how the massive creature walked and lived.

Both the Triceratops bones and the oldest T. rex—a gangly, 33½-foot-tall teenager nicknamed “Thomas” that boasts one of the most complete skeletons in existence—were collected by Chiappe and his crews during field work in Wyoming and Montana. But the displays also include the museum’s very first specimen (a lower jaw from a Canadian duck-billed dinosaur that was collected in 1919), and a number of significant finds collected for the museum by the late Harley Garbani, a self-taught fossil hunter from Hemet who died at 88 in April.

”He toured the galleries a couple of months ago, but it would have been wonderful if he could have been around for the opening,” Chiappe says wistfully.

Additionally, there are killer sea reptiles known as Mosasaurs, who, upon closer inspection by Chiappe and his colleagues were recently found to have had flukes, not long, tapering tails as scientists once imagined. Chiappe and Long say the information was there all along, but no one noticed it because the fossils had been in storage since they were found in Kansas and acquired during the 1960s.

Additionally, there are killer sea reptiles known as Mosasaurs, who, upon closer inspection by Chiappe and his colleagues were recently found to have had flukes, not long, tapering tails as scientists once imagined. Chiappe and Long say the information was there all along, but no one noticed it because the fossils had been in storage since they were found in Kansas and acquired during the 1960s.

“We have one of the best specimens in the world,” Long says, “and it had been locked up until we dusted it off and prepared it for this gallery. In doing so, we found skin and pigments and bronchial tubes and a wealth of new information, including a big tail fluke, like a tuna or a shark, that changes what we know about the way they swam and hunted.” (Stay tuned for further developments on this front. Museum sources say another blockbuster announcement about this part of the exhibit could come within the next few weeks.)

The Dinosaur Hall is part of an ambitious plan to expand and modernize the Natural History Museum, which celebrates its centennial in 2013. A groundbreaking “Age of Mammals” exhibition opened last year; a new California history hall and several other permanent exhibitions, including a 63-foot-long fin whale specimen, are anticipated before the end of next year.

Chiappe, an internationally renowned paleontologist who was recruited 12 years ago from New York’s American Museum of Natural History to supervise Los Angeles’ dinosaur collection, says the permanent exhibit had been under consideration almost from the moment of his arrival, “but we’ve worked intensively in the last five or six years.”

A native of Argentina, Chiappe says he grew up as “a city boy” in Buenos Aires, but learned from his grandfather to love the outdoors.

“We’d go hunting and fishing,” he recalls. “For a while, I wanted to be a biologist, and I went to university with that in mind. But then I met a classmate who was into paleontology, and we started going out on weekends, collecting Ice Age fossils, like saber-toothed cats and mastodons, amazing animals that don’t exist anymore. I thought it was incredibly cool.”

Chiappe has since done extensive fieldwork and research, particularly into the evolutionary links between dinosaurs and their modern counterparts, birds. The Dinosaur Hall also will address those connections.

“We will have a taxidermy pelican in a glass case, and a swan, an ostrich and a pelican skeleton,” he says. We will have a mural featuring emus, and we’ll talk about hummingbirds as dinosaurs—the idea that dinosaurs are in your backyard, and if you want to see one today, they’re right outside their window. You only need to look.”

Chiappe’s favorite displays? Well, he says, his favorite dinosaur is T. rex, and his 4 1/2-year-old son’s is Triceratops. But No. 1 on his Dinosaur Hall hit parade is the “Fossil Wall,” a 43-foot display case with nearly 100 specimens, from dinosaur bones and droppings to dinosaur eggs and skin.

“It’s beautiful from an aesthetic point of view,” he says, “and it expresses the wealth of our collection—it’s really an art installation using dinosaur body parts.”

What does he hope the public will glean from the museum’s scientific take on his favorite subject?

“I’d like people to understand that they were living animals,” he says. “We know them as skeletons. We see their bones in museums. But they were alive once. They suffered and had illnesses and diseases, and found mates and reproduced and did everything we associate with living animals, whether they are our pets or ourselves.”

Long, a fellow paleontologist who came to the museum two years ago from Australia, calls the new Dinosaur Hall “one of the most exciting dinosaur exhibits in the world,” and says it has been “a dream come true to be part of a team presenting a gallery like this.”

But, he adds, “this really is Luis’ baby.”

“It’s obviously once in a lifetime that a curator is essentially setting the course on the steering wheel for a major exhibit like this,” agrees Chiappe. “I know I won’t have another opportunity like this.”

Posted 7/7/11

Check for the latest closure information

Check for the latest closure information