New jail phone plan may be a win-win

September 8, 2011

Families of Los Angeles County inmates who’ve been forced to pay unusually high rates for collect calls from jail telephones could soon find relief under a proposed new contract that also would generate more county revenue.

Families of Los Angeles County inmates who’ve been forced to pay unusually high rates for collect calls from jail telephones could soon find relief under a proposed new contract that also would generate more county revenue.

A proposed change of vendors, outlined in a letter to the Board of Supervisors from Sheriff Lee Baca and Chief Probation Officer Donald Blevins, would cut rates for an average phone call from the county lockup by about 30% while adding millions in guaranteed annual funding for key inmate programs and jail maintenance.

Tentatively scheduled for consideration by the board on September 20, the recommendation to hire Public Communications Services, Inc., is the result of a competitive bidding process urged by critics, including Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, who complained that families were paying too much for jail phone calls and that the county was receiving too little in the existing contract’s revenue sharing provisions.

“My argument from Day One has been that if the rates were less burdensome on inmates families who were being overcharged, then more calls would be made and more money would be generated for the Sheriff’s Department,” Yaroslavsky said. “Now we have a proposal in place that hopefully will achieve those objectives.”

The price of phone calls from county jails has been controversial. Studies show that maintaining close contact with families via phone, correspondence and visits, can reduce recidivism among inmates and improve their chances of a successful reentry into society.

High phone rates deter that crucial communication. But they can also indirectly benefit inmates because, by law, the county’s portion of revenues from jail phones must go into special Inmate Welfare Funds that underwrite educational, recreational and other projects that are geared to them.

Debate over the rates charged to Los Angeles County jail phone users dates back several years to early preparations for the renewal of the current contract, which is held by Global Tel*Link Corp., a private, Alabama-based company that provides jail and prison phone systems nationally.

GTL had offered a $3.5 million fee to the county in exchange for a contract extension. The sheriff, meanwhile, argued against opening the contract to competitive bidding, saying that it might damage the department’s revenue stream.

But the supervisors and County CEO William T Fujioka insisted that putting the contract out to bid would be the best way to lower prices and maintain funding.

“I’m absolutely convinced, you put this out on the street, we’re going to get a more competitive contract,” Fujioka told Supervisors in 2008. Ultimately, in the fall of 2009, a competitive process was undertaken, leading to the new proposal.

The push for more competitive rates comes amid a shrinking competitive landscape. In fact, the winning bidder, PCS, was acquired by GTL three months after the bidding closed. GTL is among the larger firms in the prison telecommunications sector; PCS, whose customers include the Michigan Department of Corrections, was its Los Angeles-based rival.

Earlier in 2010, GTL acquired another competitor, Digital Solutions Inc., and has announced plans to acquire at least two more this year, Conversant Technologies Inc. and Value-Added Communications.

Unlike phone contracts that govern the rates of residential users, jail phone pacts have had little regulation, allowing a handful of specialized service providers to charge whatever the market will bear.

Such high prices allow carriers to offer counties lucrative revenue sharing arrangements on contracts that, in Los Angeles County’s case, have typically amounted to millions of dollars a year.

But the situation has had its downsides. Families of inmates—many of whom are among the poorest people in the county—have borne some of the highest phone rates in California at a time when the price of phone service in even far-flung places has been slashed by technology.

Under the county’s current contract, GTL charges families of Los Angeles County jail inmates $3.54 for the first minute of a collect call—more than almost every other county jail in Southern California and about seven times the price of a 50-cent pay phone call. The Sheriff’s Department gets 52% of the revenue generated by the roughly 5,400 phones in the county’s jail system—a split that last year generated about $10 million for the county’s Inmate Welfare Fund.

In contrast, the 5-year PCS plan would cut the first-minute rate to $1.25, with a 15-cent-per-minute charge thereafter. The cost for an average 17-minute inmate phone call would fall from about $5.20 to around $3.65. The new contract also would increase the county’s share of revenue to 67.5 percent, with a guaranteed minimum of $15 million annually for the Inmate Welfare Fund and $59,000 for the county’s Probation Department.

Lt. Ronald E. Gilbert of the Sheriff’s Inmate Services Bureau said PCS was one of four bidders whose names will become a matter of public record after the supervisors’ upcoming vote.

Gilbert said PCS submitted its proposal before bidding was closed in August, 2010, three months before its acquisition by GTL. The terms of PCS’ bid would be binding, despite the change in ownership, Gilbert said, adding: “They’re still their own entity. As far as the contract is concerned, we’re dealing with them as PCS.”

Gilbert said the proposal’s guaranteed revenue is especially welcome in a time of constricted state funding. In recent years, Gilbert said, the county’s share of money has dropped as steep budget cuts have prompted the release of thousands of inmates from overcrowded jails while the tough economy has forced families to limit phone time with those who remain incarcerated. Gilbert predicted that the lower prices would likely increase inmate calls, which during the first six months of this year numbered 2.4 million.

“It generates a more stable income stream for the Inmate Welfare Fund, and it benefits the inmate and family population,” he said. “Everybody seems to win on this deal.”

Posted 9/8/11

State prisoners, meet your minders

July 27, 2011

After a rare public tussle between two powerful local criminal justice agencies, the Board of Supervisors has unanimously picked the Los Angeles County Probation Department to oversee thousands of freed California prisoners who, as part of the governor’s budget plan, will no longer be charges of the state.

After a rare public tussle between two powerful local criminal justice agencies, the Board of Supervisors has unanimously picked the Los Angeles County Probation Department to oversee thousands of freed California prisoners who, as part of the governor’s budget plan, will no longer be charges of the state.

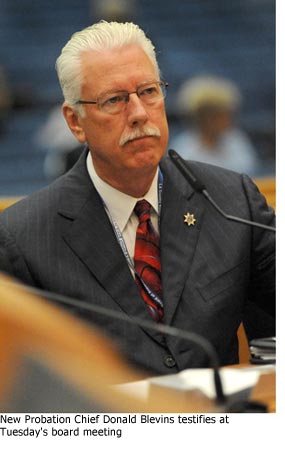

Chief Probation Officer Donald Blevins was given the nod over Sheriff Lee Baca, who had forcefully argued that his department was better suited to monitor an estimated 8,000 inmates who’ll be heading back to the streets of Los Angeles County during a nine-month period.

Critics of Baca’s proposal argued that such sweeping new duties would create public confusion over the mission of a department charged largely with suppressing crimes, not rehabilitating those who commit them. In Los Angeles and throughout the state, that job traditionally has been the responsibility of probation and parole agencies.

The board’s decision on Tuesday was based on a motion by Supervisors Michael D. Antonovich and Don Knabe, who noted that the Probation Department “has been providing supervision and rehabilitative services to adult probationers for over a century.” For that reason, they said, the agency has the kind of infrastructure and expertise that makes it best qualified to run the so-called “post-release community supervision program.” But the supervisors also called for a role for the Sheriff’s Department in identifying and, when necessary, apprehending high-risk parolees in the program.

The truth is that county officials at all levels wish they’d never had to confront the issue in the first place. Earlier this year, they argued strongly against being forced to take responsibility for the freed inmates, a key facet of Gov. Jerry Brown’s “realignment” budget strategy to save money and reduce prison overcrowding. Faced with the county’s fears about funding and strains on a local jail system already tearing at the seams, the state agreed to pay for the first year but has yet to fulfill its promises for funding beyond that.

The ex-inmates, whose releases are scheduled to begin October 1, are known as “non, non, nons”—meaning non-violent, non-serious, non-sex offenders. Under a new state law, those who violate the terms of their release will no longer be returned to state prisons. With few exceptions, they’ll serve a maximum of 180 days in county jails.

That same law also mandates that counties create an operational plan—including staffing, budget needs and re-entry services—through new multi-agency Community Corrections Partnerships. In L.A. County, the CCP will submit a plan to the Board of Supervisors for approval in August, one that is likely to include a role for the Sheriff’s Department.

Indeed, during Tuesday’s meeting Baca made clear that his department would not be relegated to the margins. “When it comes to managing high-risk parolees,” he said, “I’m not going to ask the chief probation officer for permission. I’m just going to do it.”

Obviously irritated, Baca also criticized Blevins for statements in a report to the chief executive officer in which he “literally had kind of drawn a moat around his department and looks upon me and my department as some kind of threat to the traditions of rehabilitation when, in fact, we are at the forefront of rehabilitation for parolees.”

During the meeting, Blevins, who chairs the county’ CCP, did not address Baca’s comments. But he later told the Daily News that the Sheriff’s Department would have a role in the oversight of the soon-to-arrive ex-inmates, albeit a limited one.

“Our original plan,” Blevins was quoted as saying, “was for absconders or individuals who have been working with probation but need a higher level or more intensive supervision, we would ask [the sheriff’s] assistance on those kinds of cases…The sheriff has indicated they are 24/7 and they can provide those kinds of services.”

Posted 7/27/11

The sheriff vs. the probation chief

July 12, 2011

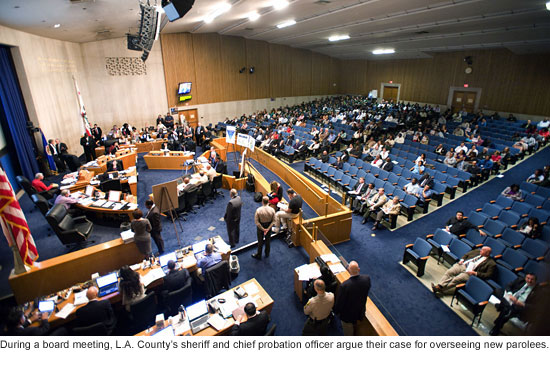

Two of Los Angeles’ most powerful criminal justice agencies faced off Tuesday during an extraordinary meeting of the Board of Supervisors, each arguing that they’d be better equipped to handle the surge of parolees who’ll soon be flowing into the county as a result of the state’s budget crisis.

Two of Los Angeles’ most powerful criminal justice agencies faced off Tuesday during an extraordinary meeting of the Board of Supervisors, each arguing that they’d be better equipped to handle the surge of parolees who’ll soon be flowing into the county as a result of the state’s budget crisis.

Under Gov. Brown’s “realignment” spending plan, California’s counties are being given responsibility for overseeing thousands of low-level state prison inmates who will be released to ease prison overcrowding and to save money. Although the state has agreed to provide funding to the counties for the first year, there are no guarantees beyond that.

Virtually everywhere else in the state, county probation departments have been tasked with these new duties, which are similar to those they already perform. But in Los Angeles, Sheriff Lee Baca has offered a novel and controversial proposal, contending that the public safety mandate of his department should be broadened to include the rehabilitative work of parole supervision.

On Tuesday, Baca took on Los Angeles County’s Chief Probation Officer Donald Blevins, who argued that his agency is not only more qualified to oversee the new parolees but that it can do so at a better price for taxpayers. The Board of Supervisors’ hearing room was crowded largely with Probation Department supporters.

The supervisors, who had strongly opposed Brown’s realignment proposal, challenged the two agency leaders to defend the content and cost of their proposals. Some expressed concerns that neither department—both of which have come under federal scrutiny for facets of their operations—could deliver on its promises. Several supervisors suggested that a hybrid of the two agencies should be considered. In the end, the board asked the Chief Executive Office to report back with an analysis of the competing proposals.

Critics of Baca’s bid contend that the Sheriff’s Department has no institutional expertise in overseeing parolees, a job more akin to social work because of its emphasis on reintegrating ex-prisoners into society. But the sheriff pointed to his record as a leading advocate for inmate rehabilitation and his department’s success in working with community-based re-entry programs.

“My department has the largest education-based incarceration program in the nation,” he said.

At the same time, Baca argued that the reach of his department could help protect the public from problems that might arise from such a large number of former inmates suddenly returning to live in Los Angeles County.

“This is a seven-day-a-week, 24-hour-a-day problem, and therefore resources must be dedicated to ensure that felons in the system understand we have the capacity to supervise them any time, any place, any time relative to the week,” Baca said.

Chief Probation Officer Blevins, for his part, acknowledged that his department has been plagued by problems in its juvenile camps. But he emphasized that it has an excellent record in supervising adults, many of whom are ex-felons and account for more than 70% of the department’s workload.

“We have a proven track record of working with this population,” Blevins said. Moreover, he said, the Probation Department could better comply with a legal mandate encompassed in the state legislation requiring the county to use “evidence-based” practices to reduce recidivism among state parolees. One probation program for probationers aged 18-25 at a county day reporting center has cut recidivism from 39% to less than 22%, he said.

The Probation Department’s plan, he said, “does not focus on suppression and incarceration over rehabilitation…It does not complicate and confuse the clients in terms of the roles and responsibilities of officers. It does not require building, learning and training to a brand new infrastructure that potentially can take years to implement and operate efficiently.”

Although the supervisors did not vote on the matter, several seemed openly wary of Baca’s plan, especially given its higher one-year cost estimate–$37 million versus $28 million for the Probation Department.

Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, for one, suggested that the board might not even be considering Baca’s proposal were it not for his reputation as one of law enforcement’s most forward-thinking figures.

“You’re unique, Lee,” the supervisor said told the sheriff. “The only reason this has been given the time of day is because you’re proposing it. If this had come from just about anybody else in law enforcement, I don’t think it would have been given serious consideration.”

Posted 7/12/11

Board reasserts control over agencies

May 17, 2011

The Board of Supervisors today formally placed two of the county’s most troubled agencies—the Probation Department and the Department of Children and Family Services—under its direct control, rebuffing a last-minute motion that called the move “impulsive” and even potentially dangerous.

The Board of Supervisors today formally placed two of the county’s most troubled agencies—the Probation Department and the Department of Children and Family Services—under its direct control, rebuffing a last-minute motion that called the move “impulsive” and even potentially dangerous.

The motion by Supervisor Don Knabe, which sought a 45-day delay in adopting the new structure, was seconded by Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas but failed to win approval by the board majority.

Supervisors Michael D. Antonovich, Gloria Molina and Zev Yaroslavsky approved the ordinance permitting the board to retake authority for managing the departments. The ordinance was tentatively approved on its first reading last week.

With the two departments no longer under supervision of the county’s Chief Executive Office, supervisors believe they will be able to obtain more timely and direct information from the departments, both of which have been plagued with embarrassing and sometimes tragic miscues.

In the case of DCFS, a series of children’s deaths has raised widespread concerns about the department’s operations and management. The agency’s director, Trish Ploehn, was reassigned to the Chief Executive Office last December and an interim replacement, Antonia Jimenez, resigned last month and returned to her former CEO post. Under the new governance structure, selecting someone to head the department now becomes a top priority for the Board of Supervisors.

As for probation, a new team led by former Alameda County probation chief Donald Blevins is working to fix problems ranging from employees’ sexual misconduct to lax management practices to poor educational outcomes for young people under its supervision. Going forward, supervisors will need to make sure those efforts stay on track and will also be at the forefront of ensuring that the department complies with a series of Department of Justice-mandated reforms.

The move to reassert control over both departments comes as supervisors consider making changes to the county’s overall governance structure. A report by Chief Executive Officer William T Fujioka and the supervisors’ chief deputies is expected to come before the board next week.

Posted 5/17/11

Board to oversee troubled agencies

May 10, 2011

In a move months in the making, a frustrated and divided Board of Supervisors voted to retake direct authority over the operations of two chronically troubled departments managed by the county’s chief executive officer.

In a move months in the making, a frustrated and divided Board of Supervisors voted to retake direct authority over the operations of two chronically troubled departments managed by the county’s chief executive officer.

Voting 3-2, the board majority on Tuesday took the first step in removing the Department of Children and Family Services and the Probation Department from the CEO’s portfolio. In the process, the supervisors erased any doubt about their willingness to modify a governance structure they created in 2007 to reduce their day-to-day management of the county’s vast bureaucracy of departments.

Voting in favor of the new structure were Supervisors Zev Yaroslavsky, Michael D. Antonovich and Gloria Molina. Opposing it were Supervisors Mark Ridley-Thomas and Don Knabe.

Because the board’s action requires a change to a county ordinance, a second vote is required next week to add children’s services and probation to several other departments that were exempted from CEO oversight and report directly to the supervisors.

For months, board members had been growing increasingly concerned and vocal about worsening problems within DCFS and probation.

The tragic deaths of a number of youngsters had ignited an uproar over issues of competency and oversight of DCFS at all levels. Last December, the agency’s embattled director, Trish Ploehn, was removed and reassigned by the CEO’s office, headed by William T Fujioka.

The Probation Department, meanwhile, was grappling with everything from sexual misconduct of employees to an inability to track nearly $80 million allocated by the supervisors to hire personnel. An internal review revealed, among other things, that management was so loose that too many employees had been hired for the department’s youth camps—a problem now being corrected by a new management team led by former Alameda County probation chief Donald Blevins.

In the case of both departments, some board members came to believe they were not being provided information necessary to understand the serious and recurring lapses for which they—as the county’s top executives—were being held accountable.

The turning point came last month when DCFS’s interim director, Antonia Jimenez, openly defied a motion by the supervisors to sign a “memorandum of understanding” with the board’s special counsel for investigating child deaths and offering possible policy reforms.

The document, signed by the top officials of eight other county departments, established protocols to ensure that the Children’s Special Investigations Unit was able to independently and efficiently review child deaths and serious cases of abuse and neglect of children under the care and/or supervision of the county.

The document also stated that the unit’s reports, prepared solely for the board, were deemed attorney/client privilege to maintain their confidentiality and thus could not be given to the departments—a provision Jimenez found unacceptable, even though she’d be allowed to read them and be given copies of any recommendations. (While earlier overseeing DCFS in the CEO’s office, Jimenez had argued that she needed copies of the reports there, too.)

Jimenez’ intransigence led to an April appearance before the supervisors that left several of them clearly exasperated.

“The other departments didn’t have a problem signing the [memorandum of understanding]. You should sign the darn thing,” Yaroslavsky told Jimenez. “Why this had to get to this point and raised to this level is beyond me. It’s really a mountain out of a molehill.”

Molina agreed, saying: “It’s shameful that we have to go through this kind of a process for something that this board has found very, very helpful.”

The board concluded by passing a motion directing Jimenez to sign the document by 5 p.m. Instead, she resigned, returning to the CEO’s team to oversee children’s services from there—a move that Antonovich later called “a blatant act of insubordination.”

Three weeks later, Yaroslavsky, Molina and Antonovich would form the three-vote majority needed to reassume authority over DCFS and probation.

“These are the two most troubled departments in the county today, and the board majority wants a more direct role in overseeing them,” Yaroslavsky said after the meeting. “The CEO will continue to partner with us, but the board will be primarily responsible.”

Ridley-Thomas, who joined with Knabe in voting against the measure, was visibly angry when his effort to have the vote delayed was rebuffed. When asked how he wanted to vote, he shouted “No!” and then added just as loudly: “Ridiculous.”

Ridley-Thomas argued that he needed more time to study a Yaroslavsky amendment to the ordinance aimed at ensuring that the new management structure would not impede the internal sharing of confidential information among departments.

Ridley-Thomas called the reluctance of the board majority to reschedule the vote “a rush to judgment” and urged his colleagues to side with him as “a point of courtesy to allow everybody to come up to speed.”

But Yaroslavsky and County Counsel Andrea Ordin both noted that the amendment had been suggested by Ordin as one of two options in a memo she sent to the supervisors last week.

Antonovich, meanwhile, noted that Tuesday’s vote was just the first of two, suggesting to Ridley-Thomas that if his concerns weren’t addressed this week’s meeting, then he’d have a chance to address them before next week’s vote.

Posted 5/10/11

Report says Probation rife with problems

August 25, 2010

In a searing critique, a top official of Los Angeles County’s Probation Department says the agency has been plagued by weak management, poor communication, entrenched perceptions of favoritism and staffers who would never have survived a rigorous background check.

In a searing critique, a top official of Los Angeles County’s Probation Department says the agency has been plagued by weak management, poor communication, entrenched perceptions of favoritism and staffers who would never have survived a rigorous background check.

“It appears that problems were ignored continuously and defective operations were allowed to ‘muddle by’ with little emphasis placed on getting back to the basics to become a high functioning organization,” Remington wrote.

Five months in the making, the report by the department’s current chief deputy, Cal Remington, provides a study in organizational dysfunction across multiple fronts, particularly in the Administrative Services Bureau, which he says affects every phase of the department. The bureau includes such responsibilities as internal affairs, budget and fiscal services and human resources.

Remington’s 67-page report—called “Back to the Basics: The Steps Required While Moving Forward”—was presented to the Board of Supervisors on Tuesday. It offers 131 recommendations to improve management, increase transparency and accountability, and improve services and staff morale while cutting improprieties and poor performance.

The supervisors mandated the report in March as the 6,100-person department, the nation’s largest, was being rocked by disclosures that, among other things, employees used county credit cards to buy electronics goods, that dozens of employees accused of misconduct escaped discipline because the investigations ran too long and that the department could not fully track $79 million allocated by the Board largely to hire personnel.

In an interview, Remington said the department already has jettisoned ineffective staffers from important middle and upper management positions “and replaced them with people who are competent.”

Remington’s proposed fixes range from sweeping strategic changes, such as developing new programs as alternatives to incarceration, to relatively quick fixes that include launching a department newsletter to boost morale. He said the department should also continue to build on a June report by the watchdog Office of Independent Review, which called for an overhaul of internal discipline.

In his report, Remington said he was surprised by the broad community interest among children’s advocates, parents, service providers and others in improving the department’s operations, only to be rebuffed by the organization. “One individual,” Remington said, “indicated that community groups have been knocking on Probation’s door for years, however, the Department would not let them in.”

That situation, he stressed, must be changed.

“The future focus of this Department clearly needs to be on community-based alternatives to incarceration; more programs focusing on families and programs that prepare juveniles and young adults to become productive citizens of the community,” Remington concluded. “This can best be accomplished by working with community-based organizations.”

Remington, a retired probation chief from Ventura County, was acting head of the department in March when he launched his study, serving until new Chief Probation Officer Donald Blevins arrived in April. He now serves as the department’s chief deputy.

He said there must be more transparency in promotions to end nepotism and cronyism that has led to a widespread “feeling that ‘it isn’t what you know, but who you know’” when it comes to promotions. Remington said managers complained to him that “unqualified candidates are promoted with systemic favoritism, nepotism, and chicanery.”

That same attitude among staffers—a sense of being on the outside—extended to the way information has sometimes been conveyed in the department, Remington said, particularly when it comes to personnel issues. This, he said, has created a workplace where “rumors are prevalent and run rampant.”

He also had some harsh words for “a few” members of the department’s executive team. These individuals were described in interviews as “being rude and having abusive ways in dealing with subordinates.” These top-tier individuals also were described as “being involved with infighting and cliques that have been destructive.”

The report urges that all managers receive mandatory ethics training and calls for the creation of a succession plan that includes a “leadership academy” to groom staffers for promotion.

To improve future hiring, Remington said standards must be raised for background checks. He said that based on his review of disciplinary cases, some employees should have been “screened out at the background phase.” Unlike most departments that hire peace officers, he said, probation does not use a polygraph to screen applicants—a shortcoming he hopes will now be rectified.

He also called for a crackdown on “work-time abuse” by staffers who fail to put in a full 40-hour week for which they’re being paid. In the interview, Remington said the extent of this abuse remains unclear. “It’s a problem we still need to look at,” he said.

The department’s 16 juvenile camps, housing 1,300 clients, were another key target for reform. This area is particularly important because the camps are the subject of an agreement with the U.S. Department of Justice, which is monitoring, among other areas, allegations of child abuse and poor mental health treatment.

Remington said all but three camp directors were interviewed at length and appear, as a group, to be “capable of effectively managing” their responsibilities. The problem, Remington said, is that they’ve “been demoralized as their roles have been shifted from leaders to passive followers.” He said they “feel stripped of the authority to operate their camp or manage their staff” when their decisions are “rescinded without explanation” from higher-ups.

Remington said this problem can be quickly corrected by simply restoring authority to these managers.

To save money and improve services, Remington recommended moving the camps’ reception and assessment units from the Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall in the San Fernando Valley to Challenger Memorial Youth Center, a complex of probation camps in Lancaster.

Despite the deep troubles at Probation, not all of the news is bad, Remington said. Some reforms have already started, and many in the department want to improve. “People here are tired of reading about the ‘dysfunctional or beleaguered Probation Department’ and they want to make a change.”

Posted 8/25/10

New turf for the sheriff’s watchdog

July 7, 2010

Veteran civil rights lawyer Michael Gennaco has focused for nearly a decade on one job: keeping an eye on the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department.

As chief attorney of the respected Office of Independent Review, Gennaco has built a model oversight unit, investigating everything from on-duty shootings to off-duty drunkenness. Although not beloved by the rank-and-file, the unit has the support of Sheriff Lee Baca and has been credited with improving the department’s training and discipline.

Now Gennaco finds himself on a new mission, one that has put him and his team front-and-center in one of Los Angeles County’s most vexing and embarrassing controversies. The Office of Independent Review, or OIR, has been recruited by the Board of Supervisors to help restore accountability and integrity to another one of the county’s criminal justice agencies—the scandal-plagued Probation Department.

It’s a new challenge—“a whole new world,” Gennaco says—but also the natural extension of his work monitoring the Sheriff’s Department and his earlier career as a widely praised federal prosecutor specializing in law enforcement misconduct and civil rights violations.

“I have a world vision in which police officers obey the law, a vision that is supported in most cases,” Gennaco says. “But there are times when they abuse their power. The victims of police misconduct don’t have power and authority and the ability to get redress. They’re not the people in Malibu.”

The mandate

In the weeks ahead, Gennaco’s team of six lawyers will be expanded to eight. He’ll send a pair of them to the Probation Department with orders to improve the speed, quality and effectiveness of internal discipline. The OIR lawyers will work hand-in-hand with the agency’s new chief, Donald Blevins, who has vowed to crack down on misbehavior and rebuild the department’s management ranks.

Although the details of the arrangement are still being worked out, Gennaco says he believes that “the expertise we have from the Sheriff’s Department will transfer over effectively.” And, the supervisors hope, quickly.

In recent weeks, the reputation of the 6,000-person department has come under withering assault amid disclosures of institutional failings and individual misconduct.

Staffers have been accused of, among other things, using department credit cards to buy electronic goods and of allowing juvenile charges to engage in video-taped brawls in probation camp classrooms. The department’s managers, meanwhile, have drawn the ire of the Board of Supervisors for being unable to fully account for $79 million that had been allocated to comply with federal mandates to improve conditions in the department’s network of juvenile camps and halls.

As county Chief Executive Officer William T Fujioka put it at a recent board meeting: “The depth of the problems in this department are shocking.”

By then, Gennaco and his team of OIR lawyers had thrown their own fuel on the fire. In a report requested by the supervisors and released last month, OIR disclosed that breakdowns in the Probation Department’s internal affairs operation had allowed dozens of employees accused of misconduct—some of it serious—to escape discipline because the investigations ran too long.

The 60-page report concluded by calling for “the establishment of a permanent independent oversight group”—a job that would promptly be added to OIR’s portfolio.

Gennaco says he’s optimistic change will come. He says the department offered “no resistance” while his team spent three months assessing the internal affairs operation and that the agency’s brass already has adopted some of his team’s 34 recommendations.

Asked whether the rank-and-file might resist his efforts, given the insular nature of law enforcement agencies, Gennaco said simply: “I don’t know.” But he added that swift, accurate investigations are in everyone’s interest, including employees who could be exonerated of wrongdoing.

On a personal level, Gennaco says, he’s “more energized than worried” about the high expectations that have been placed on him because he’s a true believer in the mission that’s been entrusted to him.

Righting wrongs

Raised in a multi-ethnic household, the son of an Italian-American dad and a Latina mom, Gennaco says his interest in civil rights started young. Two of his early heroes were Robert F. Kennedy and Thurgood Marshall. After graduating from Dartmouth College, he attended Stanford University law school and clerked for U.S. Circuit Judge Thomas Tang, the first Chinese-American on the federal bench.

In 1984, Tang encouraged an uncertain Gennaco to join the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division, despite concerns that the unit’s work ranked low on the Reagan agenda. “Judge Tang told me if there’s any time when they need good people, it’s now,” Gennaco recalls.

From his post in Washington, Gennaco prosecuted civil rights cases across 20 states, particularly in the South, and began to hone his skills on police misconduct cases. One of those cases gave him his first taste of police culture in Los Angeles when, in 1992, he successfully prosecuted a white LAPD officer assigned to the San Fernando Valley who beat a Latino teenager so severely with a baton that he sustained permanent brain injuries.

In 1994, Gennaco joined the United States Attorney’s Office in Los Angeles, where he established its first civil-rights unit and was credited with expanding the number of investigations and prosecutions of police misconduct and hate crimes. Among his most high profile cases was the prosecution of neo-Nazi Buford O. Furrow Jr., who opened fire at a Jewish day care center in the San Fernando Valley, wounding five. Furrow later shot and killed a Filipino postman.

In 2001, with the LAPD embroiled in a scandal over rogue cops selling drugs and covering up unprovoked shootings, Sheriff Baca surprised the national law enforcement community by calling for the creation of a civilian oversight unit that the sheriff hoped would provide credibility to the department’s internal investigations.

For Gennaco, the timing was perfect. After 16 years of prosecuting individual cops, he was frustrated. He had come to believe that law enforcement agencies effectively bred large-scale misconduct by failing to stamp out small-scale misbehavior early.

“When this [OIR] opportunity popped up, I thought ‘Here’s a chance’” to attack the root of the problem at one of the nation’s largest law enforcement agencies. Gennaco applied for the job and was unanimously picked by the Board of Supervisors, he says, from among 200 candidates.

Since then, Gennaco has earned a reputation as a steady and determined steward of OIR. The unit has produced dozens of reports across a wide array of issues that focus not only on the conduct of individual deputies but also on the practices and policies of the institution itself.

One, for example, led to changes in weapons training after OIR examined a high number of shootings in which deputies were firing multiple rounds. Another, more recently, led to changes in hiring standards, which OIR concluded had been loosened in a rush to increase the department’s ranks and that had resulted in the hiring of recruits with questionable backgrounds. Yet another OIR effort helped create better training for deputies assigned to the jails so they could reduce the number of suicides and homicides among inmates.

Asked for OIR’s biggest success, however, Gennaco had one word—transparency.

“Before we got here, the public had almost no information coming from the department about what kind of conduct was being alleged,” says Gennaco, who lives in Hermosa Beach with his wife of 18 months.

“There are people [in the Sheriff’s Department] who chafe a little whenever we come out with a report,” he says. “But we have to be critical of the department when we have reasons…We have a responsibility to shine a light and that’s uncomfortable.”

Perhaps the most important lesson he’s learned over the years is that civilian oversight, to be effective, must be sustained over time.

“It’s not as if you can fix the department and just go away,” he says—a conviction the Probation Department is about to experience up close.

Posted 7/7/2010

Supervisors back probation reforms

June 29, 2010

Standing along a back wall in the Board of Supervisors’ hearing room, the newly appointed chief of the Probation Department almost smiled as his bosses unanimously passed three measures aimed at restoring integrity and accountability to the troubled agency.

Standing along a back wall in the Board of Supervisors’ hearing room, the newly appointed chief of the Probation Department almost smiled as his bosses unanimously passed three measures aimed at restoring integrity and accountability to the troubled agency.

“I thought the vote was very encouraging,” said Chief Probation Officer Donald Blevins, who has little to smile about these days. “This is another example of the message I continue to get from [the Supervisors]—that we brought you in to fix a huge problem and we want to give you the tools to get the job done.”

The motions, which passed quickly and without discussion, had been tabled after Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas abstained from voting on them last week, leaving the short-handed board one vote short of the three needed for passage. Although the supervisor did not explain the move, the next day he called on the Justice Department to broadly oversee the Probation Department, saying the problems were too entrenched for the new management team to fix—a view not shared by his colleagues.

On Tuesday, Ridley-Thomas voted to approve the three motions. Supervisor Don Knabe was absent.

In recent weeks, the 6,000-person Probation Department has been rocked by disclosures that, among other things, employees used county credit cards to buy electronics goods that dozens of employees accused of misconduct escaped discipline because the investigations ran too long and that the department cannot fully track $79 million allocated by the Board of Supervisors largely to hire personnel.

Two of the motions passed Tuesday were co-authored by Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky. One, written with Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich, will expand the responsibilities of the Office of Independent Review to include oversight of the Probation Department’s internal investigations. For nearly a decade, the OIR’s work has been largely confined to monitoring the operations of the Sheriff’s Department.

The second motion—this one co-authored with Supervisor Gloria Molina—directs the CEO, County Counsel, personnel officials and others to explore within 30 days how Blevins could, under Civil Service rules, begin hiring more managers from outside the Probation Department—a break with current practices.

The third motion, authored by Supervisors Antonovich and Knabe, attempts, among other things, to insure that that no employees in the future escape discipline because of unnecessarily long internal investigations and that probation officials responsible for such lapses in the past be held accountable.

In an interview, Blevins said that, thanks to the passage of the motions, he was “pretty satisfied that we have the right tools we need now.” He didn’t rule out, however, the possibility that he’ll return to the Board for help in solving future problems.

Moving forward, Blevins stressed the need for building a management team of about four to eight people, including insiders and outsiders, that can hit the ground within 60 days. “It’s important,” he said, “to have a management team that’s loyal to you.”

He said he also wants to quickly initiate discussions with the Office of Independent Review so its attorneys can start providing the kind of tough oversight that will reduce bottlenecks that have plagued the department’s internal disciplinary system. He praised a recently completed OIR study of the department’s disciplinary lapses, saying it offered “the same conclusions I would have come to.”

On Tuesday, Blevins also presented the supervisors with a status report on the management and administration of the department, focusing on areas where the department already has begun to confront deficiencies and impose tighter controls.

Blevins said, for example, that the department is now attempting to track where each of its employees currently is assigned to work. This surfaced as an embarrassing problem after probation officials were unable to tell the board exactly how the $79 million allocated for new hires had been spent.

Blevins also said in his report he is determined to increase the department’s operational and financial efficiency by making sure staffing ratios are appropriate and that the department’s network of juvenile camps are not housing charges who would benefit from less costly community-based alternatives.

Still, despite the many problems facing his department, the well-respected probation chief sounded a positive note.

“Although there are departmental practices and procedures which have developed over many years and are within a departmental culture that is by nature resistant to change,” he said, “such resistance can be overcome as many staff and managers appear to be supportive of change to improve the Department.”

Two additional reports are scheduled to be delivered to the Board of Supervisors next month. One is an assessment undertaken by Chief Deputy Cal Remington and the other is a report by county-hired consultants on the juvenile probation camps.

Posted 6/29/10

Probation reforms temporarily tabled

June 22, 2010

A series of measures aimed at swiftly improving the management and accountability of L.A. County’s scandal-plagued Probation Department was put on hold Tuesday when a short-handed Board of Supervisors could not muster the three votes needed for passage.

A series of measures aimed at swiftly improving the management and accountability of L.A. County’s scandal-plagued Probation Department was put on hold Tuesday when a short-handed Board of Supervisors could not muster the three votes needed for passage.

The matter was delayed a week after Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas—one of only three members present—left the board one vote shy by abstaining. Supervisors Zev Yaroslavsky and Gloria Molina, both of whom have been outspoken in their efforts to reform the department, had voted to move the measures forward.

Ridley-Thomas declined Molina’s offer to explain why he abstained at a time when the department is under increasing pressure to quickly restore public confidence. “I don’t know why anybody would object to these…motions,” said Molina, the board chairman. In fact, Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich, who is out of town, had encouraged his board colleagues in an e-mail to press ahead, despite his absence. He called the motions “vital.”

In recent weeks, the 6,000-person department has been rocked by disclosures, including reports that employees used county credit cards to buy electronics goods, that dozens of employees accused of misconduct may escape discipline because the investigations ran too long and that the department cannot fully track $79 million allocated by the Board of Supervisors to hire personnel.

The three motions at issue on Tuesday were intended to provide the department’s newly named chief, Donald Blevins, with ways to increase the effectiveness of his management team and provide tougher oversight of the department’s internal investigations and discipline.

Two of the motions were co-authored by Yaroslavsky. One, written with Antonovich, would expand the responsibilities of the Office of Independent Review to include oversight of the Probation Department. For nearly a decade, the OIR’s work has been largely confined to monitoring the operations of the Sheriff’s Department.

The second motion—this one co-authored with Molina—asks the CEO, County Counsel, personnel officials and others to explore within 30 days how Blevins could, under Civil Service rules, begin hiring managers from outside the Probation Department—a break with current practices.

The third motion, authored by Supervisors Antonovich and Don Knabe, attempts, among other things, to insure that that no employees in the future escape discipline because of unnecessarily long internal investigations and that probation officials responsible for such lapses in the past be held accountable.

At Tuesday’s meeting, Yaroslavsky emphasized that “time is of the essence”—a sentiment that brought agreement from Blevins, the former probation chief of Alameda County. He said he understands the board’s “clear message” that it’s his job “to clean up the department.”

Posted 6/22/10

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink