Bingo! Beach restoration’s a winner

May 22, 2013

Just in time for the unofficial start of summer, Venice Beach has landed some national bragging rights as one of the best restored beaches in the country.

The recognition from the American Shore and Beach Preservation Association honors the $1 million restoration of a 650-yard-long stretch of Venice Beach that was severely eroded by winter storms of 2004 and 2005, and walloped again—although less severely—in 2010.

The restoration—known as “nourishment”—served to widen key areas, protect county buildings, minimize erosion and make it easier for sand to build up naturally during the summer months.

“A year and a half later, we’re looking at super-wide beaches,” said Charlotte Miyamoto, planning division chief for the Department of Beaches and Harbors.

The 2011 restoration project required transporting 30,000 cubic yards of sand from an area north of the Venice breakwater to the damaged area near county lifeguard headquarters, about a half mile south.

Venice Beach shares top honors with six other beaches around the country, including Delray Beach in Florida, Nags Head Beach in North Carolina, Pelican Island in Louisiana, and the Edgartown beach on Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts.

Lee Weishar, who chaired the ASBPA committee that assessed the contenders, said that beach restoration funding, particularly from the federal government, has been hard to come by in recent years. But he noted that Hurricane Sandy provided a dramatic wakeup call, with unrestored beaches damaged more profoundly than those that had been “engineered” with restoration projects.

“It’s a hard way to learn that a restored/engineered beach makes a big difference,” he said.

Miyamoto, of Beaches and Harbors, said that as the county plans for climate change, more beach restorations may be on their way.

“These are things that we’re going to have to continue doing,” she said.

Posted 5/22/13

A surf pioneer gets his day in the sun

May 16, 2013

A new holiday celebrating the diversity of Southern California’s beach life has been quietly gathering momentum at the Santa Monica Pier.

Nick Gabaldón Day. The name may not be familiar now, but it’s about to get bigger, starting with an all-day event June 1 on one of Santa Monica’s most storied beaches.

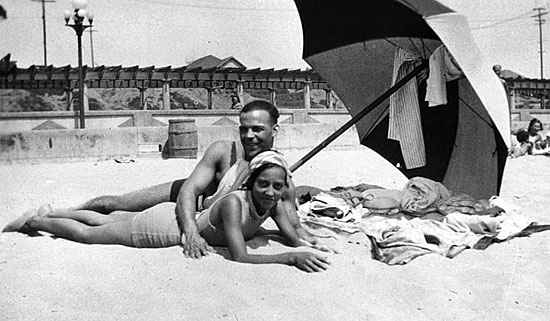

Launched by a group of historians and surf enthusiasts with the support of Heal the Bay and other organizations, the event honors Nicolás Rolando Gabaldón, the first Southern California surfer known to be of African-American and Mexican extraction.

Gabaldón grew up in Santa Monica and surfed on a stretch of shore colloquially known as “The Inkwell” because it was one of the few beaches during the Jim Crow era on which black beachgoers were welcomed. He went on to surf in Malibu with some of the biggest names of the sport’s formative decades.

For years after his death in a 1951 surfing accident, he was all but forgotten, a casualty of the cultural myopia of a racially fraught era. But in recent years, he increasingly has become a rallying point for cultural historians, environmentalists, surfers, inner city groups and others who want the beaches to feel more inclusive.

Five years ago, the City of Santa Monica dedicated a plaque honoring his contribution to surfing, and at least two documentaries since then have focused on his story and the history of African-American surfers. Last year, Heal the Bay and the Santa Monica Conservancy partnered with black swimmers, surfers and divers to combine a coastal cleanup day with a lesson on Gabaldón and the history of The Inkwell, an experiment that led to this year’s more elaborate celebration.

The event, which starts with a paddle-out on the south side of the Santa Monica Pier, will include free surf lessons (click here for reservations), documentary screenings and a beach reception with Los Angeles County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas. Organizers—who include the Black Surfers Collective, the Santa Monica Conservancy, the Surf Bus Foundation, the California Historical Society and Ridley-Thomas’ office—say they are hoping it will lead to an official annual observance.

“Surfing has always been a multicultural activity, but we’ve been denied access through gates that are sometimes legal and sometimes not,” says Rick Blocker, a retired Leimert Park schoolteacher and founder of BlackSurfing.com, a web site that recognizes surfers of color.

Adds Meredith McCarthy, Heal the Bay’s program director: “It’s a way to bring people to the beach who may have never felt welcomed, and a way to start connecting to communities.”

Wayne King, 85, who knew Gabaldón as a Santa Monica High School surfing buddy, jokes that if his friend were still alive, “he’d never believe it—he was just an ordinary guy in the neighborhood.”

King himself was a child when his family moved to Santa Monica from Missouri in 1937. “We were in segregated schools and couldn’t go to school higher than sixth grade back there. My parents knew if we were to have any kind of a chance, we’d have to move to California.”

His father became a welder at Douglas Aircraft Co., King says, and the family settled near 19th Street and Delaware Avenue, in a neighborhood of mostly black and Latino families. King liked to swim, having learned while playing on rafts in the Mississippi River. The Gabaldóns—they were divorced, he says, and Nick lived with his African-American mother—lived a few blocks from the King house. Inevitably, the boys met on the sand.

Today, he notes, his old local beach is one of the swankiest on the Westside, situated between Bay and Bicknell streets just south of the Casa del Mar hotel. In those days, however, it was much narrower and rocky. Nonetheless, on weekends, the sand filled with African-American and Latino families, and the kids who were fortunate enough to live within walking distance developed a level of comfort there that their inland contemporaries didn’t share.

Over time, he and Gabaldón made friends with some white lifeguards who had noticed that the two boys enjoyed bodysurfing.

“They had one of those big, old-time wooden boards and asked us if we were interested, and they and a couple of other kids in the neighborhood, the Pilar brothers, taught us to board surf,” he remembers. It was “exhilarating”, he says, and eventually, he and Gabaldón bought their own boards and began looking for bigger waves to tackle, a challenge that drew the easygoing young black men into a culture that was dominated by white and Pacific Islander surfers.

It also forced Gabaldón to eventually buy a car, King says, because motorists on Pacific Coast Highway were so reluctant to pick up a black man. At least once, he says, Gabaldón told him he’d paddled all the way from Santa Monica to Malibu on his surfboard, a legendary trek that inspired the name of one of the documentaries about him, “12 Miles North: The Nick Gabaldón Story.”

“We were like a pair of flies in a bowl of buttermilk,” he laughs. “But we didn’t really get a hard time from other surfers. People who hang around the beach are a different breed—they might look at you funny at first, but once you got in the water, you were all the same.”

The two remained friends as Gabaldón joined the Navy, then returned home to attend Santa Monica City College. King recalls being on the beach the day his friend died.

“It was 1951, the first week of June,” King recalls. “He decided he wanted to shoot the pier, go in between the pilings. All of a sudden, this rogue wave came up and he disappeared.”

King, who now lives in Altadena, eventually became a 32-year City of Santa Monica maintenance worker. “I spent 11 or 12 years cleaning those beaches, and I never went back in the water,” he says now. “Seems like after Nick passed, I just lost interest.”

Others did not, however. After Surfer magazine did an article on black surfers that mentioned Gabaldón in the early 1980s, Blocker began questioning his Malibu surfing buddies.

“People said, ‘Oh, yeah, that black guy in the ‘40s and ‘50s? Yeah, he was here.’ Well, to me, that attitude seemed wrong. His story seemed to me like one that needed to be remembered.”

So, picking up where Surfer magazine had left off, Blocker began writing, and his research found its way to Alison Rose Jefferson, a Los Angeles historic preservation consultant and doctoral candidate in history at UC Santa Barbara.

Jefferson, who was researching race and the history of Southern California’s leisure spaces, had her own interest in Inkwell beach and the community around it. Her work, and that of Blocker, in turn, drew the attention of Heal the Bay, which last year involved Blocker in efforts to toughen pollution limits in the county’s municipal storm water permit.

Jefferson views the interest in Gabaldón as part of a broader move to reclaim history among groups who have felt left out. But, she adds, raising his profile through alliances like this one also broadens the influence of groups like Heal the Bay, and reminds African-Americans and Latinos throughout the region that they, too, have history with California’s coastline and a stake in what becomes of it.

“Nick Gabaldón was a quintessential Californian. He’s multi-ethnic, part of his family immigrated to this country, and he participated in the California dream, pursuing his passion,” she says. “And people of color want clean water, too.”

Posted 5/16/13

Want a happy camper? Be first in line

February 27, 2013

There’s a secret to getting your kid into a great summer camp: Sign up before spring.

Unfortunately, most parents remember that secret just as the school year is ending. But for those who do register early, Los Angeles County is a summer playground of options.

Here’s a sampling of what’s out there. Act quickly. Some already are selling out.

- Enrollment opened last week for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art summer art camp, and some weeks are already fully booked. Several are still open, though, with artist-led workshops for art-loving kids aged 6-13. The camp runs from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. starting June 10, and proof of age is required. Tuition is $365 per week ($325 for NexGen members). Financial aid for art camp is also available. For more information, call 323-857-6512 or click here.

- Sign-ups also opened this month at the popular Summer Nature Camp at the Los Angeles County Arboretum & Botanic Gardens, which offers weeklong sessions of outdoor and indoor fun for children aged 5-10. The program runs from 9 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. with extended care from 8-9 a.m. and 3:30-5 p.m. if parents need it. Sessions start June 10 and run through the week of August 5. Tuition excluding extended care is $300 a week for Arboretum members and $335 for non-members. Half-day sessions also are available, and there’s a 10% sibling discount. For more information, call 626-821-4623 or click here.

- Another big crowd pleaser is the Adventures in Nature Day Camp at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, which offers sessions in everything from fossil labs to filmmaking for kids in kindergarten through 8th grade. Registration opens March 1 for the weeklong sessions, which start June 24 and run through the week of August 5. Program hours are 9 a.m. to 3 p.m., with extended care from 8-9 a.m. and 3-5 p.m. if needed. Tuition excluding extended care is $250 a week for members and $300 a week for non-members. A limited number of scholarships are available. To sign up early, watch this space. For more information, call 213-763-3348 or click here.

- The Mountains Restoration Trust’s Discovery Nature Camp for little naturalists has some good news and some bad news. The bad news is that it will only be available for one week—the week of June 24—this summer, and there are only 18 available spaces. The good news is that if you’re reading this, you could be first in line. The camp, which operates out of a historic farmhouse in the Santa Monica Mountains, offers hands-on interaction with nature for children aged 8-12. Hours are from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. and tuition for the week is $260. For more information, call project manager Susan Haugland at 818-591-1701 or click here.

- Nothing says summer in SoCal like Junior Lifeguards, but good programs can require some advance swimming prep. Registration for returning junior guards in the Los Angeles County Fire Department’s program starts March 4. This year’s program runs Monday through Friday from July 1 to August 2, with morning or afternoon sessions in crucial ocean skills for kids aged 9-17. Fee is $476 and financial aid is available. New registrants must show proof of age and pass a swim test. Experienced Junior Guards 16 and over can qualify for the department’s Cadet Program. For much more information, or to find the camp nearest you, call 310-939-7214 or click here.

- The surf and beach camps traditionally operated by the Los Angeles County Department of Beaches & Harbors are still on hiatus, due to budget cuts. But plenty of community beach programs have arisen to fill the gap in the meantime. For a list of community-based summer youth camps operated at local beaches, click here.

- Just keeping an eye out for kid-friendly outings? Check out SummerSounds at the Hollywood Bowl. A music festival designed just for little ones, SummerSounds features two concerts daily through July and August, at 10 a.m. and 11:15 a.m., plus arts and craft workshops, for kids 3-11. The music ranges from gospel to mariachi to reggae to traditional Filipino music—and it’s a bargain. Tickets aren’t on sale yet, but traditionally they have been $7 regardless of age and $5 for workshops. For more information as summer approaches, watch this space.

Posted 2/27/13

Storming the beach as runoff flows

December 6, 2012

The first storm of a Southern California winter can be welcome and even romantic. Not so the aftermath—or as clean-up crews at the beach wryly call it, “The First Flush.”

“Those big storms really clean out the creeks and the catch basins,” says Carlos Zimmerman, assistant chief in the facilities and property maintenance division at the county Department of Beaches & Harbors, and a 33-year employee of the department. “Everything washes down—trees, bushes, firewood, plastic bottles, foam containers. Tons and tons of trash. Dead dogs and cats. Snakes. All kinds of things, you wouldn’t believe it. I saw a BMW come out of Topanga Creek once.”

That’s why, as rainstorms pelted Southern California last weekend, county and municipal crews were hitting the beaches to clean up debris. Their efforts are just one of the ways—from pending litigation to an upcoming Clean Water, Clean Beaches ballot measure—in which runoff will be front and center this winter in Los Angeles County

“Things like education efforts and ordinances against single-use plastic bags and polystyrene containers are making inroads, but it’s obviously an extreme problem,” notes Kirsten James, water quality director at Heal the Bay, the environmental advocacy organization.

Debris, she notes, is just the most visible pollution that courses into the ocean after a rainstorm. (This is one reason why health officials recommend staying out of the ocean for 72 hours after a rainstorm.)

“Heavy metals and bacteria are in there as well,” James says. “Some years, [the First Flush] looks like you’re not even in a First World country—more like you’re at a dump than at the beach.”

Kerry Silverstrom, chief deputy director at Beaches & Harbors, says that county beaches get runoff from more than 200 storm drains, as well as from Ballona Creek, which dumps runoff from miles inland into Santa Monica Bay. Though “trash catchers” installed throughout the system in recent years are intercepting more and more garbage, some still is making it down to the shoreline. Because storm water often continues to flow long after a heavy rainfall, and the debris it carries can churn on the waves for days before being washed up by high tide, the cleanup after a storm usually lasts long after the clouds part.

“That was one of the surprises when I first came to Beaches & Harbors,” says Silverstrom. “I had no idea that there was as much winter work on the beaches as summer work.”

That winter work, done by year-round maintenance crews, can mean anything from tending beach restrooms to piling sandbags to pulling lifeguard towers back from the pounding surf. Kenneth Foreman, chief of the department’s facilities and property maintenance division, says nearly 80 county workers were deployed at a dozen coastal beaches after last weekend’s rain storms, from equipment operators with sand-sanitizing machinery to hand crews who walked the high-tide line, plucking scraps of litter.

The winter crews, he adds, start at 6 a.m. and work every day, rain or shine, including weekends. “We worked Saturday and Sunday, even though it was storming,” he says. “Often by the time the general public hits the beach, they have no idea how dirty it was before they got there.”

There are things the public can do to help limit beach pollution, from proper disposal of motor oil and animal waste to keeping trash out of the storm drains to letting local stormwater coordinators know if flooding occurs in your neighborhood from trash-clogged catch basins.

On a longer-term level, the Board of Supervisors will conduct a January 15 public hearing on whether to seek property owner approval of the Clean Water, Clean Beaches measure through a mail-in ballot. The measure, prompted in part by toughened federal clean water standards, would raise $270 million for stormwater projects in Los Angeles County by assessing parcel owners based on the amount of runoff they generate (about $54 a year for a typical single-family residence.)

Meanwhile, cleanup crews will be fighting the good fight on a landscape that, when the storms hit, still too often becomes long on odor and short on scenery. At a Santa Monica city beach near the Pico/Kenter storm drain, a Heal the Bay staffer blogged last Friday morning that the sight and stench were “shocking.”

“I . . . saw runoff flowing fast out onto the Santa Monica beach, carrying along with it strong smells reminiscent of motor oil and gasoline, hundreds of plastic cups, chip bags, soda cans, an unusually high number of tennis balls, plastic bags (some full of pet waste), bits of Styrofoam, bottle caps, and more urban detritus,” blogged interactive campaigns manager Ana Luisa Ahern, who posted some haunting pre-cleanup photos on the organization’s web site.

“It was a saddening and somber sight, to say the least.”

Kenneth Foreman Sr. of Beaches & Harbors, in jacket at far right, hits the sand after last weekend's storms.

Posted 12/6/12

County pools offer more than a dip

July 3, 2012

The water’s fine and so are the learning and exercise opportunities at Los Angeles County swimming pools, which recently opened for the summer season.

“We do a lot of different things at our pools,” said Kaye Michelson of the county Department of Parks and Recreation, which manages the pools. “We have recreational swimming at set times. We also have aqua aerobics for adults, dive clubs, water polo—and most of those programs are free.”

People of all ages can take introductory swimming lessons from county lifeguards for just $20 for ten classes over a two-week session. For adults, the pools can serve as a reasonably-priced alternative to a gym membership—morning and evening adult lap swimming is $7 per week or $25 per month, and aqua aerobics are $15 for two weeks of classes.

The pool at El Cariso Park in Sylmar has a full roster of additional water activities. Kids ages 7 to 17 can learn diving, competitive swimming, synchronized swimming or water polo, and swimmers ages 9 and up can join in on triathlon training—all for free. See the El Cariso Pool schedule for details.

Pool safety is always a major focus, so lifeguards will be keeping an eye on swimmers and sharing their expertise. The Department of Parks and Recreation has also compiled a list of guidelines to follow.

“We want kids and parents to learn good safety tips that they can use anywhere, at any body of water,” said Michelson.

All 25 county pools are open daily for recreational swimming from 12:30 p.m. to 5 p.m. until Labor Day. Proper swimwear is required. Entrance is free, and guests ages 6 and under must be accompanied by an adult.

Posted 7/3/12

Riding to the rescue for 100 years

May 16, 2012

Bathing beauties were still posing on county lifeguard trucks in 1959. Photo/LA County Lifeguard Assn.

Summer isn’t summer in Los Angeles County without the bright yellow vehicles of the beach patrol.

“Iconic” is how Chief Lifeguard Mike Frazer described them last week as the Board of Supervisors gave the Department of Beaches and Harbors authority to sign a proposed agreement to take ownership of the fleet’s latest additions—45 custom-built Ford Escape hybrids that the county has leased since 2008. Under that proposed agreement, Ford Motor Co. would continue to advertise itself as the “Official Vehicle Sponsor” of the L.A. County beach lifeguards. So far, however, Ford has not agreed to a transfer of ownership.

Outfitted with state-of-the-art rescue equipment, the vehicles have saved not only lives but also more than $267,000 a year in fuel costs. “We’ve come a long way,” Chief Frazer says.

In fact, as the photo gallery below shows, beach rescue vehicles have come farther than Southern Californians might imagine. And to look back at their history is to dip into the region’s evolving—and sometimes dangerous—relationship with the beach.

Arthur Verge, an El Camino College history professor and veteran county lifeguard, notes that there was a time, not so long ago, when Southern Californians regarded the ocean as a frightening place that was best admired from afar. “Drownings were sadly common,” Verge says, adding that those who did go into the water often had no idea how to swim or how to get out of the powerful rip-currents that swept them out to sea in their heavy wool bathing outfits.

Professional ocean lifeguards didn’t even exist here until the early 1900s, when the City of Long Beach and real estate developers Abbot Kinney and Henry Huntington began paying “lifesavers” to reassure tourists outside the Long Beach Plunge and to promote the then-new developments of Venice and Redondo Beach.

Notably, Kinney and Huntington turned in 1907 to George Freeth, a celebrated Hawaiian surfer who not only trained L.A. County’s first generation of lifeguards but also pioneered rescue response.

“While fire departments were using horse-drawn rigs,” Verge says, “George Freeth, as early as 1912, was patrolling the beaches of Redondo, Hermosa and Manhattan Beach with a motorcycle, carrying a metallic rescue can in a special sidecar.”

Other early lifeguards were more low-tech.

“Santa Monica’s first lifeguard, ‘Cap’ Watkins, patrolled the beach on horseback,” Verge notes. “And George Wolf, the first Los Angeles city lifeguard, rode back on forth from Venice to El Segundo on a bike.”

By the late 1920s, both the city and county had lifeguards and trucks that ferried their gear along the boardwalks. That gear was stretched thin in the 1930s as the county lifeguards took over the beaches in the economically struggling South Bay.

“We didn’t get any new vehicles until the late ‘40s because World War II was on,” recalls Cal Porter, an 88-year-old retired county lifeguard and Malibu surfer. “If somebody had a bad rescue…we’d jump into this old 1933 International we had and head down Pacific Coast Highway. We’d be going as fast as we could, lights and sirens going—but all the other cars would be passing us.”

With wartime came the 4-wheel-drive jeep, developed by Willys-Overland Motors for the U.S. Army. The Willys allowed lifeguards for the first time to skip the boardwalk and drive directly across the sand. The jeeps were redeployed onto county beaches in the late 1940s; some remained in use for the next twenty years.

By the 1960s, the county had a fleet of Ford trucks with special racks for lifesaving equipment. Beaches filled with Baby Boomers and, occasionally, the products of the era’s experimental mood: In 1970, the county bought two customized dune buggies from the designer Meyers Manx. “But they didn’t work,” Verge says. “Sand would get into the carburetor.”

Lifeguard operations consolidated in the mid-1970s under the county, which by 1975 had the world’s largest lifeguard organization—a distinction that brought marketing opportunities. Among them was the chance for car companies to become the “official” rescue vehicle supplier to the now renowned L.A. County beach lifeguards.

Kerry Silverstrom, chief deputy director of the county Department of Beaches and Harbors, says that in 1986, Nissan and the beach lifeguards signed an agreement. “They got name recognition, ad copy and the ability to say they’re the official vehicle of the County beaches,” she notes, “and we got to use their vehicles for free.”

Nissan’s deal—releasing 30 chrome yellow 4×4 King Cab lifeguard trucks and six light pewter Stanza wagons onto the county beaches—lasted until 1994, when Ford won the contract. Nissan got it back in 1999, but Ford made another comeback with the hybrid SUVs in 2008.

Frazer says lifeguards were accustomed to pickup trucks with gas engines, and concerned that sand might damage hybrids. “But one of our missions is to protect the environment, so we said, ‘Let’s see if this works.’ ”

He says the results have been striking.

“The visibility is amazing and the turning radius is almost twice what we had, so we can navigate crowds better,” he says. “It has traction even in places like Point Dume, which has a steep sloping beach. “

Silverstrom says the relationship with Ford has been a financial and environmental lifesaver as the economy and the Internet have made branding rights a tougher sell at beaches. As for the next generation of vehicles, Frazer says the lifeguards “continue to look at all the options.” After all, only 100 years have passed since George Freeth rode to the rescue on his motorbike.

Posted 5/9/12

Stopping a danger in the sand

April 4, 2012

Rescuers work feverishly to uncover a teen in Newport Beach who was buried for 30 minutes but survived.

The county’s new beach ordinance may have launched more than its share of wisecracks about allegedly outlaw Frisbees, but lifeguards say that at least one of the less-discussed changes could save lives—and that’s no joke.

The new law, which won final approval from the Board of Supervisors on Tuesday, bans the digging of holes deeper than 18 inches to avert dangers not widely known to beachgoers, said Los Angeles County Lifeguard Section Chief Mickey Gallagher.

“In my 40-year career, people have been badly injured and even killed as a result of sand tunneling,” he said. “This is about a safety hazard. It isn’t about little kids with plastic shovels digging a little hole in the sand.”

Last August, for instance, a teenager was buried alive for more than 30 minutes in Newport Beach. The then-17-year-old boy was building a tunnel when the sand collapsed around him. He survived, several feet below ground, only because he had managed to wiggle his head a little as the sand poured in around him, creating a slight air pocket that kept him alive long enough for emergency crews and bystanders to get to him.

Two months before that, in June 2011, a Northern California teenager on a beach outing with a church group was permanently disabled after being buried for more than 10 minutes when a sand tunnel collapsed on him.

In the same week, according to Los Angeles County lifeguard records, a 10-year-old boy in Manhattan Beach was rescued from a similar situation—only the top of the boy’s head was showing when the lifeguard found him. He’d been lying on his back in a hole, tunneling laterally, and had ignored a prior warning to stop digging because it was dangerous.

Nine months earlier, on Labor Day weekend, a 3-year-old toddler was taken by air ambulance from Zuma Beach to Harbor-UCLA Medical Center after she crawled into a sand hole that had collapsed on her, county lifeguard records show.

And two months before that, on July 25, 2010, an 11-year-old boy burrowing in Manhattan Beach was buried for five minutes as more than a dozen beachgoers, emergency workers and lifeguards tried frantically to extricate him. Lifeguards later said that the only reason they even located him was that his cousin had run, screaming, for help and one of his rescuers had glimpsed a patch of his blue swim trunks as they dug blindly under the sand’s surface. By the time he was pulled free, his lips were blue and he had stopped breathing; he vomited sand after a physician who happened to be at the scene administered mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

“Sand is really unstable, even when it’s hard-packed,” said Gallagher. “Every year, someone will try to dig a deep hole, or tunnel in from a steep berm after a high tide and get into trouble. Some people actually come down to the beach with big shovels, like you use in construction.

“People think they can make a tunnel or a cave, and to the untrained eye, the sand may seem fine because it’s wet. But without support, those tunnels will collapse, and sand is extremely heavy. And once someone is buried, it’s extremely hard to find them. And there’s no oxygen down there.”

The revisions to the beach ordinance make a number of other clarifications to the existing rules for recreation at the beach. Among other things, they make clear for the first time that Frisbees and footballs are allowed on the beach, albeit with certain restrictions. (Basically, you can do it anytime except when it endangers someone or a lifeguard deems it unsafe.)

Inaccurate press reports initially drew criticism of the changes, including the ban on digging, which was derided as meddlesome fun-killing. But Beaches & Harbors Director Santos Kreimann says lifeguards requested the digging restrictions so they could have legal backup in preventing a problem they’ve informally been guarding against for generations.

Beyond dangers to the diggers, Kreimann said, holes in the sand also create a hazard for emergency workers, who are jolted by them when they transport people with neck and back injuries.

“The bottom line is: Have a good time and play in the sand if you want to,” Kreimann said. “But don’t dig more than knee-deep, and if you make a hole, fill it back up.”

All that's left: the hole in Newport Beach where sand swallowed a 17-year-old boy. Photo/Los Angeles Times

Posted 4/3/12

Tough times, good partners

March 20, 2012

For the past several years, all of our county labor unions have gone without a pay raise. In the case of our sheriff’s deputies, firefighters, lifeguards, probation officers and public defender investigators, it’s been three straight years.

Now they’re about to make it four in a row.

With the Board of Supervisors’ approval this week of another one-year contract extension with our public safety labor partners, I thought it was time to pause for a moment and say thank you. Our employees’ willingness to step up to the plate in these difficult times is one of the reasons our county finds itself in much better shape, relatively speaking, than most other municipalities throughout California, as well as the state itself.

Our unique and healthy partnership with labor, together with the long-running fiscal discipline shown by the Board of Supervisors, is paying dividends as we continue to weather a difficult economic environment.

I’m not saying that it’s been easy, or painless. But we have gotten through the financial crisis to date without having to lay off or furlough a single employee. This is particularly important in these tough times, when demand for the county’s safety net services soars.

Thanks go as well to my board colleagues and to our Chief Executive Office. Together with our labor partners, I believe we’ve created an atmosphere of mutual trust—one in which relatively modest sacrifices today help avert far more painful consequences tomorrow.

I’ve written in this space before about how we’ve gotten to this point—how our current policies of prudence and restraint grew out of the lessons learned during a financial rough spell back in the mid-1990s when the county was spending beyond its means to the tune of $1 billion a year. That wake-up call, shortly after I joined the Board of Supervisors, is an alarm that none of us wants to hear ever again.

So now, as we see other local and state governments in tumult around us—and as we continue to grapple with hard choices in our own budget—we can take satisfaction in what we’ve been able to accomplish together.

All of our employees are still working. They’re still putting food on their families’ tables. And they’re still serving the people of Los Angeles County. And in this economic environment, that’s a remarkable thing.

Posted 3/20/12

Seeking ultimate clarity in beach law

February 15, 2012

The beach-loving Ultimate Frisbee community has a message for the Board of Supervisors: Game on.

Several Ultimate Frisbee devotees, concerned about the impact of a new beach ordinance on their sport, came to the Hall of Administration Tuesday to give supervisors a piece of their minds—but ended up giving them a tutorial on the game, too.

“I don’t know what Ultimate Frisbee is. I’m sure it’s a great sport…But if you’re throwing projectiles around a beach when there are hundreds of thousands of people at the beach, the public safety comes first…It’s common sense that we’re asking you to employ,” board chairman Zev Yaroslavsky told the visiting players before asking them to explain their game.

“It’s a team sport. On the beach, it’s four on four or five on five, on a football-type field, not that big, with two end zones. And you advance the disc by throwing it to people on your team and you score by throwing it to a teammate in the end zone,” explained Alison Regan, a member of the Los Angeles Organization of Ultimate Teams, or LAOUT.

Yaroslavsky wondered how that would work in the midst of summer beach crowds: “So on a 90-degree day in Santa Monica in July or August, I would imagine it’s pretty tough to find space to have a game like this?”

“The beaches are large enough that we usually find some room,” Regan replied. “But we have to be accommodating, you’re right. When the public wants to walk through, we have to stop our play and we let the public walk through.”

It was the growth of new beach sports such as beach tennis and soccer that led to a recent liberalization of the county’s rules on ball-playing on the sand.

However, widespread erroneous media reports last week claimed that the county had enacted $1,000 fines for football and Frisbee playing at the shore, sparking a local uproar that quickly was heard ’round the world.

Although Department of Beaches and Harbors director Santos Kreimann moved to clarify the policy, saying that the new rules actually permitted football- and Frisbee-playing as long as it didn’t endanger other people on a crowded beach, the Ultimate Frisbee contingent was still troubled.

Tiffany Wallace, who plays on Solidarity Ultimate, which she described as a social justice Ultimate Frisbee team, said people should be allowed to use “Frisbees, footballs, soccer balls, even Ping Pong balls” at the beach without prompting “selective enforcement” under a too-vague ordinance.

Her sister, Julia Wallace, also addressed the board. “If the law is on the books, that’s enough to cause fear,” she said. “So it actually has to change.”

The board agreed. Supervisors, acting on a motion that Supervisor Don Knabe had submitted before the players testified, ordered a rewrite of the Frisbee- and ball-playing section of the new ordinance.

The new language should clearly state that “such activities by small groups and individuals are allowed at all times on the County beach” unless lifeguards direct otherwise for public safety reasons, the motion said.

Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas suggested that the players come back for an Ultimate Frisbee demonstration sometime.

And on their Facebook page, Ladies of La—Women’s Ultimate Frisbee, the disc-hurling activists declared victory.

Posted 2/15/12

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink