Helping homeless families heal

November 24, 2014

Gabriele Gonzalez was living a hard life last winter. She was homeless and addicted to methamphetamine, sleeping in parks and abandoned buildings, unsure where she’d find her next meal.

Today, she’s headed in a dramatically different direction. She lives in a comfortable room in a freshly-refurbished residential treatment center, has a new job in customer service, and is looking forward to a possible reunion with the three children—aged 6, 8 and 10—who were taken away from her when she was at her lowest point.

Her transformation has not been a solo voyage. Crucial assistance is coming from the Via Avanta Residential Center in Pacoima, where a pilot program called “Project 60: Women and Children” is underway to help homeless women, particularly mothers, with serious mental illnesses.

The program marks the latest extension of Project 50, a pioneering “permanent supportive housing” program launched by Los Angeles County in 2007. It provided 50 of the most vulnerable homeless people on Skid Row with housing first, and then surrounded them with mental healthcare, substance abuse treatment and other services. Project 50-style programs have since expanded to assist nearly 1,000 people across the county, said Mary Marx, who oversaw the initial effort for the Department of Mental Health. The initial investment paid off, too—saving $4,774 per person over the first two years by keeping them out of jails and emergency rooms. And the model has spread to cities including Denver, San Francisco and Washington, D.C.

And, of course, to Pacoima, where for many in the women’s pilot program, the well-being of their children serves as a powerful motivator to turn things around.

“I had lost apartments, cars and jobs before, but I had never lost my kids,” said Gonzalez, 29, whose son and two daughters were removed last November by the Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services and placed with relatives. “When they got taken, I lost a big part of me. I couldn’t imagine having them grow up with the idea that I didn’t fight for them.”

At a court date last January, Gonzalez realized that she was running out of time to get her kids back. Motivated to take action, she turned to a list of help numbers provided by DCFS and decided to call Via Avanta, which is run by Didi Hirsch Mental Health Services. She moved in on February 5, 2014.

Kita Curry, president and CEO of Didi Hirsch, said that having children involved presents special challenges and raises the stakes of the housing program.

“We’re not just helping an individual get their life together; we’re helping a family get their future together,” Curry said. “Otherwise, these kids would be at risk of trouble at school, getting in bad relationships and repeating the cycle.”

Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky—an early supporter and pioneer of the housing-first approach—identified $542,000 in 3rd District homelessness funding to refurbish one of two residential buildings at Via Avanta last year. Last month, he directed an additional $1.7 million to the facility to redo the second building.

Though only a year old, the women’s program already is making a difference. It has served 39 women since the beginning of 2014. All were homeless and suffered from severe mental illness. Many also came with substance abuse disorders. Some, like Gonzalez, no longer had custody of their children. Others were admitted with children in tow. So far, 16 have been discharged and 23 remain in treatment. Of those discharged, 88% went on to live in supportive housing or with spouses, family and friends. Half moved out with their children and the others continue to work toward reunification.

Unlike Project 50—which dealt with single homeless people, most of them men—this program must consider the safety of the children and the realities of parenting, Curry said. Raising kids can be stressful even without mental health issues and substance abuse challenges, so it’s important to ensure that the women can cope with those realities before they are discharged.

After moving in, Gonzalez felt an immediate sense of security knowing that her basic needs would be met. She began putting her life back together, piece by piece—going to group therapy sessions, working in the kitchen and attending classes on subjects such as parenting, safety, domestic violence and relapse prevention.

“At first I was very emotional,” Gonzalez said. “I would cry in every group. It was part of my healing process.”

After a month or so, Gonzalez was allowed to have visitors, but she first needed to mend the bridges she had burned with members of her ex-husband’s family, who have custody of her children. The kids now visit occasionally, and Gonzalez has tea parties, plays dress-up and reads to them. She’s seen them “about 10 or 11 times. I’ve had to sit back and be OK about the fact that I’m not going to get as many visits as other people, but I‘m doing what I can.”

In addition to working on mental health and substance abuse issues with counselors, she built a resume and did mock interviews at Chrysalis, a nonprofit employment agency that works with Via Avanta. After spending hours each day applying for jobs at the work center’s computers, three weeks ago she was hired to do customer service for online companies. She wakes at 4 a.m. each day to commute from Pacoima to her workplace in Glendale. In her spare time, Gonzalez plays piano and even sings in Via Avanta’s hallways. Her current favorite is “Someone Like You” by Adele.

Gonzalez is adamant about taking responsibility for her life, but, like many homeless women, she also must come to terms with a long series of youthful traumas, including rape, molestation and abuse. By 15 she was diagnosed with clinical depression. Married at 18, she spent the next 12 years in a troubled relationship and turned to drugs, she said, to deal with her inner pain.

At first, she was reluctant to accept help in coming to terms with her past.

“I guess I held that stigma that I’m crazy if I have to see a therapist,” Gonzalez said. “I was very anti-medication. But it made such a difference. The medication and therapy has helped me so much.”

Now she’s looking ahead to the new year. February looms as an important month. That’s when she expects to move from Via Avanta (the program is generally geared to short-term stays) and has a custody hearing scheduled on the 15th.

“Hopefully that will be the date that I reunite with my kids,” she said.

Someday, Gonzalez hopes to attend nursing school and help other women like herself, perhaps at a place like Via Avanta. But she doesn’t want to get ahead of herself. She planes to continue focusing on her mental health and substance abuse issues by staying in treatment and going to 12-step meetings.

“I’ve put in a lot of work but none of it would have been possible if I hadn’t come here,” Gonzalez said. “I’m looking at life in a new way. I love myself today.”

Posted 11/21/14

Staging Grand Park’s biggest act yet

August 28, 2014

The pink furniture is being packed off to storage. The splash pad is disappearing under a protective mat. The street closure notices have been circulating for a week and a security detail of more than 1,000 has been assembled.

With Grand Park scheduled to welcome its biggest crowd yet this Labor Day weekend, local authorities have mustered a similarly impressive response to gear up for Budweiser Made In America, the two-day downtown music festival being curated by Jay Z and promoted by Live Nation.

“There are a lot of headline acts and they’re expecting more than 30,000 people each day,” explained Christine Frias, a program manager in the county CEO’s office who is coordinating the departments involved in the deployment.

“I think, with the help of Grand Park, the Sheriff’s Department and all the collaboration that’s going on, this event will be successful. “

Still, she notes, “you have to take extra precautions when there’s going to be alcohol.”

Preparations for the August 30-31 festival have been the talk of the town since April, when Jay Z and Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti announced that the bicoastal music festival would be held this year in downtown’s most popular new park.

Though Grand Park has seen some grand crowds—about 20,000 gathered there for its first New Year’s Eve bash, for instance—they have mostly been free to the public and explicitly family friendly.

And peaceful: Frias said the more than 10,000 people who gathered there for July 4 music and fireworks were so well behaved that none of the park’s plants or furnishings had to be replaced.

But the Budweiser MIA concert is the first attempt to use the 12-acre space as a venue for a major ticketed rock concert, and—though neither Jay Z nor his superstar wife, Beyoncé are among the acts on the lineup—this event is expected to be a doozy, with Kanye West, John Mayer and other big names on the roster. More than 30 bands are expected to play over the festival’s two days.

Three stages, an amusement park ride and an exhibition skate park will dot the lawns between City Hall and the Music Center, and 40 to 50 food trucks will ring the venue. And while all ages will be welcomed, the festival site will allow beer drinking at more than a half-dozen public and VIP beer gardens.

“It’s going to be a couple of long hot days, and hopefully people will mostly consume water, but we are concerned about alcohol consumption,” said Los Angeles Sheriff’s Capt. Chuck Stringham.

About 270 sheriff’s deputies and a similar number of Los Angeles police are expected to be deployed on each day of the festival, along with several dozen Music Center security officers and an unknown number of undercover officers who will be enforcing laws against underage drinking for the state Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control.

Another 370 private licensed security guards are expected to be on hand at the behest of the acts themselves and the concert promoter, according to a spokeswoman from Garcetti’s office. The Sheriff’s Department will handle security within the event perimeter and LAPD will be in charge outside.

Alcohol will be permitted only in the beer gardens, and patrons will be limited to two beers at a time and required to produce valid photo I.D.s, he said, adding that attendees will not be allowed to exit and re-enter the venue.

Frias said the park itself will be braced for the masses. Grand Park is owned by the county and operated by the Music Center, although the surrounding streets are mostly the jurisdiction of the City of Los Angeles. Live Nation is paying $500,000 to the city to cover its costs and $600,000 to the Music Center to cover park rental and county services.

But the promoters must pay extra for any damage, and more than 300 workers per day have been on the site this week, spending an average of 15 hours a day to assemble about 100 tractor trailers’ worth of equipment, according to a spokesman for Live Nation.

Videographers have been filming the lush grounds all week, she said, to establish the park’s pre-festival condition, and the park’s signature hot pink furniture has been stored for safekeeping.

Vulnerable landscaping is being cordoned off with temporary fencing. And, she said, the splash pad around the Arthur J. Will Memorial Fountain also is getting a custom buffer to protect it from a stage that is being installed over it for the festival deejays.

“The splash pad will be turned off and dried, and then they’re putting a 4- to 5-inch rubberized mat on it to cover it and distribute the weight of the equipment on top of it,” said Frias.

Outside the Lines, the construction firm that helped build the splash pad, will oversee the construction to ensure that none of the festival preparations damages the water feature or surrounding tile and LED lights, she said.

Perhaps the trickiest set of preparations is for festival traffic. Already, various downtown streets have been closed this week for delivery of production equipment and stages. (Most of the work has gone on overnight).

Though ticket sales are not as high as the initial daily estimates of 50,000, the crowds are still expected to set records for Grand Park, and organizers have spent months reassuring downtown residents and business owners that the area won’t be inundated.

“But we’ve had major closures in the downtown area before—we know how to do this,” said Aram Sahakian, who oversees special traffic operations for the city Department of Transportation.

On the Fourth of July, for instance, he noted, thousands cars were swiftly ushered in and out of downtown parking structures by traffic control officers who patrolled the park area on foot and on Segways.

“And how about Fiesta Broadway? That used to bring in hundreds of thousands of people,” Sahakian said.

Organizers are urging concertgoers to take public transportation, Sahakian said, and between 7,000 and 10,000 are expected to ride mass transit into the venue. But the Civic Center station—which opens directly into Grand Park—will be closed so that riders can’t bypass the ticket-takers, and to accommodate safety concerns.

Though the Civic Center station does have a second entrance outside the perimeter of the festival, event organizers and law enforcement insisted that the whole station be closed because the bottleneck that would have resulted from channeling thousands of riders at one time into one exit might have overcrowded the platform and created a safety hazard, said Metro spokesman Marc Littman.

So subway riders are being urged to get off at Pershing Square or Union Station and walk the few blocks to the venue.

Meanwhile, Sahakian said, those who drive will be directed to downtown parking garages, though some may have to park as far from the venue as Staples Center or Dodger Stadium, and ride in on shuttles. Extra traffic engineers and traffic control officers will be on hand to help channel traffic toward open parking structures, he said.

“Yes, this is a first time thing for the park, but we’re prepared,” he said. “Hey, we moved the Space Shuttle, right?”

Budweiser Made in America curator Jay Z performing earlier this year with event headliner Kanye West.

Posted 8/28/14

Turning 50, to applause

April 3, 2014

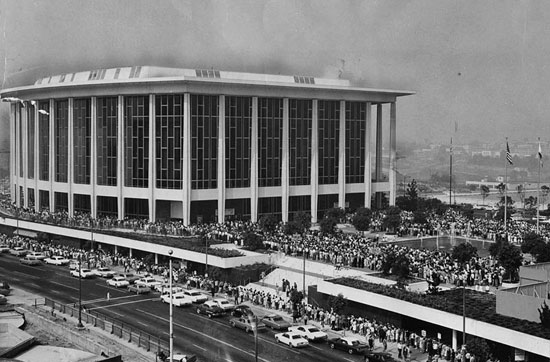

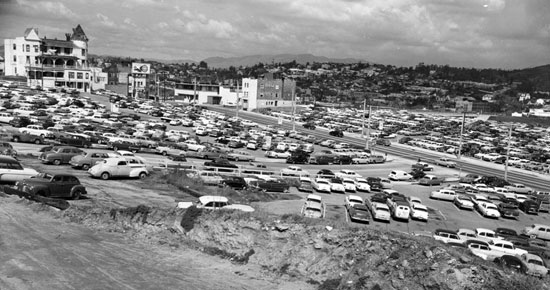

Within a year, the Music Center was a cultural fixture in L.A. Here, thousands of people line up for "Hello, Dolly" tickets. Photo/Herald Examiner

Like any grand dame, she avoids dwelling on birthdays. Still, a half-century is a milestone for a cultural icon in L.A.

So fans of the Los Angeles Music Center have gotten off to an early start in celebrating her upcoming 50-year mark. This week, a launch party on the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion stage kicked off a months-long celebration that will include some 60 large and small programs, including a gala on her December 6 golden anniversary and a public bash the next day on the Music Center Plaza.

“The Music Center has been critical to Los Angeles’ culture,” says Board Chair Lisa Specht. “We’re one of the top three performing arts centers in the country, along with Lincoln and Kennedy Centers, and for decades, we’ve been a hub of creativity.”

Not to mention a game-changer for L.A.’s metropolitan evolution.

“The Music Center was a major turning point in L.A. coming into its own in the postwar era as a major American city,” says Teresa Grimes, a Los Angeles historic preservation consultant who has documented the Center’s architectural heritage for past restoration projects.

Though the Los Angeles Philharmonic had been well established, it had no permanent home at the end of World War II other than the Hollywood Bowl, which was forced to close in 1951 due to a financial crisis, Grimes says. A series of “Save the Bowl” concerts, orchestrated by Dorothy Buffum Chandler, the wife of the Los Angeles Times’ publisher Norman Chandler, reopened the beleaguered band shell, but underscored the cultural shortcomings of the burgeoning city.

The winners of a Cadillac Eldorado, part of Dorothy Chandler's fundraising drive for Music Center construction.

Between 1951 and 1954, plans for a civic auditorium and convention center had been put on the local ballot three times, but never garnered the two-thirds majority it needed for passage. So in 1955, Chandler and the local Symphony Association began raising private funds for a hall to house the Philharmonic, which for years had been playing in leased space. As the highlight of their gala kickoff at the Ambassador Hotel, they raffled off a new Cadillac El Dorado.

“That was the beginning of it all,” Chandler is quoted as saying in Grimes’ Historic American Buildings Survey. “When we raised $400,000 in a few hours on El Dorado Night, I knew southern Californians wanted a music center badly enough to build it themselves.”

The effort took nearly a decade, at a time during which Downtown L.A. was being radically redeveloped. It required legislative approval and involved civic leaders from Donald Douglas to the Irvine family to Cecil B. De Mille.

Led by their arm-twisting society matron and her family newspaper, the Music Center boosters powered through social barriers dividing the Pasadena elite from Westside show business people, overcame pushback from provincial politicians, outlasted an economic downtown and triumphed in a last-minute squabble over whether the Center would be situated at First and Hope Streets, where the county wanted to put it, or at Chandler’s preferred location, the summit of Bunker Hill.

Chandler won, bumping the planned Department of Water and Power Building to the next block as the once-stately—and by now shabby—community of Bunker Hill was razed beyond recognition. She also brought on the architect of her choice, Welton Becket, who had worked with her on the Hollywood Bowl comeback and had master planned the campus of UCLA.

When Chandler decided during a visit to Europe that a single concert hall wouldn’t suffice, and that the new facility would do better financially if it also had a theater and a smaller forum, she won that battle also. Eventually, her tenacity in the project would put her on the cover of Time magazine.

The ultimate cost of the project was $33.5 million, with some $19 million of it from private contributions, including more than $2 million in small cash donations that local citizens dropped in so-called “Buck Bags” that were designed by Walt Disney and placed at cultural gatherings.

On December 6, 1964, the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion opened, resplendent with its crystal chandeliers and gold-leaf ceiling; the Mark Taper Forum and the Ahmanson Theatre were dedicated two years later. Opening night featured the renowned violinist Jascha Heifetz performing Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D Major, and the Los Angeles Philharmonic conducted by a 24-year-old Zubin Mehta.

In the ensuing years, everyone who is anyone has performed at the Music Center, from Ingrid Bergman and Nat King Cole to Neil Young and Ravi Shankar. Esa-Pekka Salonen and Simon Rattle made their American debuts at the Music Center, as did groundbreaking productions from “Angels in America” to “Zoot Suit.”

Between 1969 and 1999, most of the Academy Awards ceremonies were held there. The Dorothy Chandler Pavilion is where Sacheen Littlefeather refused Marlon Brando’s Oscar, where a naked man streaked onto national television behind David Niven and where Sally Fields exalted at being really liked by the Academy.

And countless Angelenos have memories of youthful jobs as Music Center ushers.

“I worked there as an usher during my senior year of high school,” recalls William Estrada, now curator and chair of the History Department at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. “It was the days of Zubin Mehta and we were required to wear these heavy, long Nehru-type jackets that were just awful to wear in the summer. Dorothy Chandler had her own parking space, and sometimes one of us was selected to walk her from her car to her seat.”

Today, Estrada notes, the Music Center, built on the site of the old Bunker Hill community, is just one cultural component in a downtown cityscape that is hardly recognizable compared to its pre-1960s, World War II incarnation. And it has expanded: The LA Phil is now housed at Disney Hall, the Center’s latest venue, and the L.A. Opera is at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion.

Nonetheless, some things change more than others: this week’s anniversary kickoff was sponsored by Cadillac.

Click here to buy tickets to anniversary events and to share your memories of the Music Center, and here to volunteer.

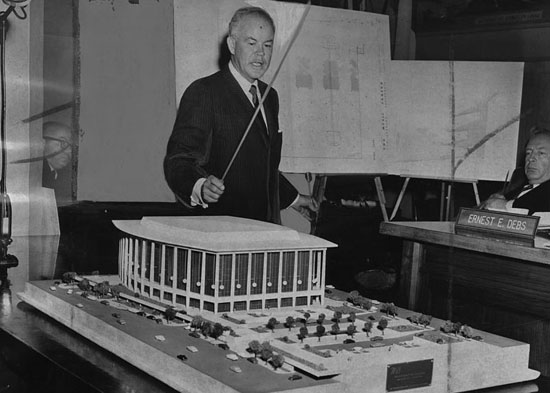

Architect Welton Becket presents plans for the new Music Center to the Board of Supervisors in 1960.

The Music Center was built as a public-nonprofit partnership on county land but was underwritten by private donations. Photo/Herald Examiner

The Mark Taper Forum went up in 1966, covered with a mural of precast terrazzo. Photo/Herald Examiner

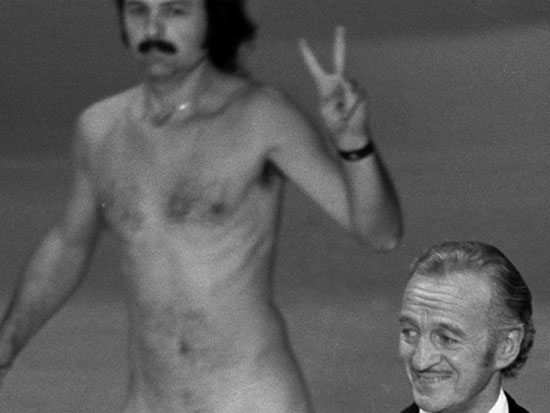

Some memorable moments occurred during the Music Center's reign as the Oscar's home. In 1974, a streaker crashed the party and actor David Niven's presentation.

Posted 4/3/14

Defenders mark a century of L.A. law

January 19, 2014

In this 1963 photo, Public Defender Kathryn McDonald confers with client Gregory Powell (left), who was accused with Jimmy Lee Smith in the "Onion Field" killing of LAPD officer Ian Cambell.

In the early 1880s, an Italian immigrant in San Francisco was charged with trying to collect $500 in insurance by torching his house on Telegraph Hill. The man was innocent but could not afford a decent attorney, and when his trial date rolled around, his lawyer didn’t show.

So the judge, as judges did then, went into the hallway and ordered the first lawyer he saw to represent the defendant. This didn’t bode well, since most court-appointed defense lawyers at the time were not only unpaid but also incompetent.

The lawyer—Clara Shortridge Foltz—was, in fact, just out of law school. But she won the case and used it as Exhibit A in a national push that led to the opening of the nation’s first public defender’s office in 1914 in Los Angeles.

One hundred years later, the Public Defender’s Office of Los Angeles County is marking its centennial anniversary. Some 700 attorneys work there now—more than at any criminal defense firm in the nation—along with hundreds of investigators, paralegals, psychiatric social workers and support staff. Last fiscal year, they defended clients in more than 400,000 felony and misdemeanor cases, not counting the thousands more defendants in juvenile delinquency and mental health courts.

Like Foltz, they occasionally make history. And, like Foltz, they tend not to become particularly famous. (In 2001, when the criminal courthouse downtown was renamed in her honor, the Los Angeles Times noted “a chorus of people saying: ‘Clara Who?’”)

“We usually pick up cases because nobody else is there,” says Alan Simon, a now-retired public defender bureau chief who spent five mostly unsung years representing the Hillside Strangler, Kenneth Bianchi.

“But most of the great names in public defense are not the ones that you see in the headlines. Charlie Gessler was probably one of the best defense lawyers ever. Do you know who he is? Probably not.”

Deputy Public Defenders Bernadette Everman and Dave Meyer at arraignment of "Night Stalker" Richard Ramirez.

Less obscure are some of the names of the clients represented over the years by the department. The Night Stalker had a public defender. So did the Onion Field killers and members of the Manson and Menendez families. Public defenders played a key role in uncovering the Rampart scandal at LAPD in the 1990s, and handled the crush of cases filed in the wake of both the Watts Riots and the L.A. Riots.

Most of the office’s clients, however, are the kinds of people to whom society tends to pay little attention—the impoverished, the downtrodden, the lost, the addicted, the difficult.

“It’s a calling,” says Public Defender Ron Brown, who has spent 33 years in the office, where turnover for reasons other than retirement averages a miniscule 2 percent a year.

“Our clients aren’t always nice people,” Brown says. “But somebody has to defend them, and vigorously defend them, in order for justice to be done. So what we do is about protecting peoples’ constitutional rights, and people who work here find that this is a place where they can do God’s work, as corny as that may sound.”

As integral as the Public Defender’s Office now is to the legal system, it was a radical notion when it began. It arose from decades of lobbying by Foltz, whose long list of accomplishments included being the first female lawyer in California. With fellow suffragettes and Progressive allies, she sought to balance the odds in the late 1800s against impoverished defendants who were often railroaded by ambitious prosecutors and judges, even though they were supposed to be presumed innocent.

At the time, the state prosecuted people suspected of criminal wrongdoing, but didn’t underwrite any of their defense costs. A judge could appoint a lawyer to represent a pauper. But the court-appointed attorney, who was duty-bound to take the assignment, had to work without pay, or pro bono.

As a result, few competent lawyers made themselves available for such work. Instead, judges typically drew from the lowest ranks of the courthouse pecking order, often strolling out into the hallways and grabbing whoever happened to be around.

Foltz was outraged by the situation. A lawyer’s daughter, she had turned to the law to support herself after her husband deserted her and their five children. She had a soft spot for the poor.

She also had a knack for agitation: When she learned that only white males could become lawyers in California, she hounded the governor into signing landmark legislation to abolish the inequality. When she couldn’t’ get into law school, she sued for admission. Now, pressed into action on behalf of poor clients, she believed the time had come for lawyers like her to be able to make a living.

So she began agitating for legal reforms that would guarantee a paid defense and balance the odds against the defendant. According to a definitive biography of Foltz by retired Stanford law professor Barbara Babcock, she spent three decades campaigning in state legislatures and drafting model statutes before a political tide of Progressives and women—who had just gotten the vote here—led to success in California.

By then, Foltz was working as a deputy district attorney in Los Angeles County, another first for a woman, and was an influential political voice, both nationally and here. In November 1912, Los Angeles County voters approved a charter that included the creation of the Office of the Public Defender, and the following year, it was ratified by the state legislature.

After a competitive exam, the Board of Supervisors appointed Walton J. Wood, a Los Angeles deputy city attorney, as the first public defender in the nation. The office opened on Jan. 9, 1914.

Over the years, according to Public Defender Brown, the office’s focus has changed with the societal landscape.

“In the past, we looked exclusively at winning—at getting the guy out and moving on,” he says. “The thought was that we’re lawyers, not social workers. But in fact, a good lawyer really is a kind of social worker. You end up getting involved with everything from housing to mental health needs.”

To that end, the office now works closely with social services in the county, from children’s services to mental health. It also has helped pioneer the use of specialized courts for addicts, veterans, the mentally ill and women, and has become involved in communities with programs like Parks After Dark.

And as it heads into its next century, he says, the department has added to its diversity in ways that would probably please the suffragette who made it happen: More than half of the lawyers—from trial lawyers to managers—are female now.

Clara Shortridge Foltz's groundbreaking activism led to the creation of L.A. County's Public Defender's Office in 1914, the first of its kind in the nation.

Posted 2/21/14

Embracing a second chance

November 25, 2013

Gratitude is rare in criminal courtrooms, but for the women gathered on a recent Friday before Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Michael Tynan, thanksgiving was everywhere.

One was clean after an addiction that had crippled her since age 7. Another was in sober living after 30 years of shuttling between Skid Row and prison. Yet another was a middle-aged ex-con when she hit her deepest bottom, and she wept as she described the redemption she shared with the five women beside her.

“I was so tired,” 55-year-old Donna Majors said last week, as prosecutors and parole officers brushed away their own tears at the small graduation ceremony in Tynan’s downtown courtroom. “And I was given the chance to finally face my demons, to know who I am and finally be at peace.”

If the emotional scene seems a far cry from standard L.A. criminal justice, it may be because the program that spawned it is a departure as well. Since 2007, the Second Chance Women’s Re-Entry Court has been among the most successful diversion programs in Los Angeles County, offering an intensive yet cost-effective alternative to prison for hundreds of high-risk female felons.

The program targets parolees and probationers charged with new offenses, channeling them into a 6-month residential substance abuse treatment program in lieu of another term behind bars. That rehab, at the nonprofit Prototypes residential center in Pomona, is followed by up to 18 months of tightly supervised outpatient treatment, plus services ranging from parenting classes to educational and vocational training.

Judge Tynan greets program alum Georgina Moore, who presented him with a picture of her and her daughter.

Each woman checks in regularly before Tynan, who consults with therapists and court officers to determine when a participant can move to the next level of treatment. Those who relapse or reoffend return—often remorsefully—to county jail or prison, but most move on to sober housing, family reconciliation and even jobs and college.

At last count, 295 women had been formally admitted and 61 had gone back to jail or prison, according to a recent review conducted by the Public Defender’s Office. About 90% of the recidivists, the review found, were women who had not yet completed their treatment.

Of the 125 who have graduated so far, the review found, only eight—about 6%—have since gone back to jail or prison. By comparison, according to state figures, the recidivism rate in 2011 was 55.1% for female inmates.

“You’ve come a long way,” the judge told a glowing ex-con at the most recent graduation ceremony, glancing at a file that included her latest report card from Mt. San Antonio Community College. “You got an A at Mt. SAC! Congratulations! Gimme a hug! I remember when you came through that door looking like something the cat wouldn’t have dragged in on a bet.”

Well into his 70s, Tynan notes that he could be retired. But the judge—who also presides over the county “drug courts” and alternative sentencing programs for the mentally ill, military veterans and others—says that his is a labor of love.

This has been particularly true lately, he adds, as funding concerns have been looming over the program because of a new state law aimed at putting the brakes on California’s burgeoning state prison population. Under the AB 109 law, known as “realignment,” the county, rather than the state, has been given responsibility for supervising and incarcerating offenders whose most recent convictions are for non-serious, non-violent, non-sexual offenses.

But because the Women’s Re-Entry Court is largely underwritten by a state grant for parolees, women who once were prime candidates for the program—street people, hustlers and others whose long criminal histories stem from drug habits—are now ineligible because the state no longer supervises them.

And the county, which now oversees these offenders, doesn’t directly fund its Re-Entry Court participants. Under AB 109, these offenders are being channeled into other, less intensive programs underwritten by realignment money. If they re-offend now, they can only be placed in Re-Entry Court if an alternative funding source pays for their treatment—a grant for AIDS patients, for example, or for pregnant women.

Meanwhile, officials say that parolees who remain under state supervision now often require special consideration to get into the program, because they are more institutionalized, with more serious convictions.

Shari Crome, an assistant unit supervisor with the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, says she’s frustrated “because I’ve been here almost since the beginning of the program, and I’ve seen the successes. There’s nothing else like it in the state, and it works.”

Deputy Public Defender Nancy Chand, a key member of the re-entry court team, congratulates the grads.

Deputy Public Defender Nancy Chand, who has represented most of the Re-Entry Court women, calls the AB 109 funding snag a rare sour note in a program that has transformed some of the most desperate lives in L.A.

“These women are really scarred,” Chand says. “Most come in with horrific trauma, and were victimized as children, enduring severe physical, sexual and emotional abuse and abandonment. Some can’t read and write. Some can’t work. Eighty-one percent have one or more mental health diagnosis and 50 percent have two or more. As one of my clients put it, they’re literally scraped off the streets.”

Currently, Tynan says, about 60 women at any given time are enrolled in the program, a little more than half of them paid for through the $500,000 annual state correction’s grant and the rest covered by a shifting and uncertain patchwork of federal, state and county grants to Prototypes.

The cost is about $18,000 a year for each woman, versus an incarceration cost of close to $50,000 a year in prison or more than $36,000 a year in county jail, not counting medical and mental health care. Officials at the Public Defenders Office estimate the program has saved tens of millions of dollars; many of its participants had been facing jail or prison sentences of 10 years or more.

Barbara Dunlap, for instance, was a 58-year-old homeless addict with 15 prison terms under her belt by the time she entered the program.

“I discovered alcohol before I started school, and I started school at the age of six,” Dunlap says. Her babysitter sold her to men when she was a child and by 21, she says, she was a prostitute with a criminal record. By the time her public defender sent her to Tynan’s courtroom, she was a 58, suffering from AIDS and hepatitis and was wheelchair-bound as the result of surgery stemming from a poisoned heroin injection.

Now 61, she is sober, living in permanent supportive housing, enrolled in college classes and a mentor at Prototypes. And at the ceremony in Tynan’s courtroom, she addressed the most recent graduates from her electric wheelchair, rolling back and forth across the courtroom, testifying like a preacher as a dozen state corrections officials watched from the jury box.

“When they found me, I was on the streets, and I don’t even know how they told me from the sidewalk—I was cold, my life was filled with stench and I was gray, without any life in me,” she proclaimed, her voice trembling.

“But they treated the whole woman—my health issues, my substance abuse issues, my anger issues. I didn’t know that anyone understood people like me.”

Taking the podium in Dunlap’s wake, the graduates told their own harrowing stories, weeping with gratitude as they thanked their therapists, probation and parole officers, prosecutors and defenders, families and, of course, the judge.

Brigitte Benjamin, 52, told the group that she had spent 30 years on Skid Row, and had expected to die there. Now, she is in a sober living facility and working toward her GED after 30 years on Skid Row.

Helen Navarro credited Tynan and Prototypes with forcing her to confront the roots of her addiction for the first time in the 20 years she had spent cycling in and out of prison on robbery and burglary charges. “I didn’t want to go deep-deep-deep,” said Navarro, a 51-year-old recovering crack addict—now sober and working as a receptionist at a country club in the San Gabriel Valley. “The counselors made me look at myself.”

Sandy Raymond, a 48-year-old mother of two who had lost more than half her life to crack addiction, did a little dance as Tynan handed her a certificate of completion. “I didn’t know nothing but going in and out of jail and stealing stuff,” she said. “But now I’m a secretary. I love my life.”

Over cupcakes and high fives from their families, the women also quietly gave thanks for the inner strength they were able to muster.

Brandishing her graduation certificate after decades of crime and addiction, Mary Willis said that for the first time in 25 years, she now has a relationship with her children. “I will always keep in the back of my mind what Judge Tynan told me,” she said proudly. “Give yourself a chance.”

Posted 11/25/13

How to see Endeavour ride into sunset

October 11, 2012

So it won’t be The Rock. The access will be tighter and the pageantry slighter than when LACMA’s 340-ton boulder rolled through town.

Early reports had raised hopes that the move of the Space Shuttle Endeavour from LAX to the California Science Center would become a rolling parade like the one that accompanied the immense granite stone in Michael Heizer’s “Levitated Mass” at LACMA. But as logistical realities set in, it became clear that the Endeavour, which has a 78-foot wingspan, is about four times as wide, six times as long and twice as high as the “Levitated Mass” boulder.

Moreover, the spacecraft requires a 10-foot clearance on each side because it is covered in a special lightweight, silica-based, thermal insulation so fragile that raindrops can dent it. Its wings can’t be removed and replaced like an airplane’s. And to the chagrin of many, hundreds of trees had to be cut down to accommodate Endeavour’s massive silhouette.

“It’s so big that the street is barely wide enough in some places to accommodate the shuttle itself, let alone the crowd control on the sidewalk,” says LAPD Sgt. Rudy Lopez.

“It’s a safety issue,” agrees project director Marty Fabrick of the California Science Center Foundation, noting that the crews operating the shuttle’s special transporter will have their hands full just maneuvering it under power lines and around corners with scant clearance between the wheels and the curb. “They have to have 100% focus on what they’re doing. We don’t want them distracted by the worry that someone will fall off a curb and get hurt.”

But that doesn’t mean there won’t be plenty of chances to glimpse the cross-town progress of “Mission 26”, as it’s been dubbed. From organized events to wide spots on the 12-mile route, thousands are expected to witness the spacecraft’s road trip, which begins at about 12:01 a.m. Friday, October 12, when it pulls out of its United Airlines hangar en route to the Science Center, where it’s expected to touch down Saturday night. (Click here for a schedule and here for a route map.)

Updated 10/12/12: Endeavour’s last ride is underway. Check out this video posted at Curbed L.A. to see the craft crossing Sepulveda Boulevard.

Despite the disappointment that has arisen since the Los Angeles Police Department announced that sidewalks on much of the route would be closed for safety reasons, Fabrick promises that “people will have ample opportunity to see this historic move.”

Two planned celebrations are scheduled for Saturday, and at least two pit stops will offer a decent view of the shuttle, as will some parts of Crenshaw Boulevard for those lucky enough to live nearby. Locals along the route also will get a good look as the Endeavour passes homes, malls and markets, as well as landmarks such as Inglewood City Hall.

Some 700 LAPD cadets and volunteers will be doing crowd control and event security, and police have urged spectators to expect large crowds, heavy traffic and delays. And lots of street closures: Access to the south side of Los Angeles International Airport will be restricted during the move for security reasons, for example, and the shuttle’s planned 2:30 a.m. exit from LAX via Northside Parkway will be open to credentialed media only.

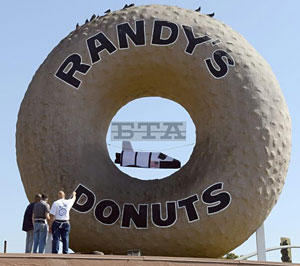

Despite the little Endeavour in the donut hole, Randy's will be closed to the shuttle-viewing public Friday afternoon.

Also, the Friday night crossing of the 405 Freeway at the Manchester Bridge will be a tougher ticket than some might expect, given the location. The California Highway patrol will be closing ramps and running traffic stops to discourage gawking, and the crossing itself isn’t scheduled to take place until sometime between 10 p.m. and midnight.

And just as a side note: Though it might be tempting to try to catch the crossing at, say, Randy’s Donuts, the iconic shop with the giant doughnut just off the freeway, don’t bother. Larry Weintraub, the owner, had initially been expecting a large crowd of shuttle enthusiasts and had even added a mini-Endeavour to the hole of his famous doughnut.

But because of the many sidewalk closures, he ended up instead renting his lot to Toyota, which expects to bring in about 150 people to film the crossing.

The company —a longtime corporate supporter of the science center—agreed to tow the Endeavour across the overpass with a Toyota Tundra pickup truck and a specialized dolly. The maneuver is needed because Caltrans’ weight distribution requirements for the bridge called for a different tow mechanism than the Endeavour’s transportation system.

Even though Randy’s will be closed to everyone but Toyota guests on Friday after 2 p.m., the shuttle should be easily visible from several formal and informal venues. Among the better opportunities:

La Tijera Boulevard and Sepulveda Eastway in Westchester

A commercial lot, this will be the shuttle’s first layover, on Friday from about 4:15 a.m. until about 1:30 p.m. Donation of the space—look for the Citibank and the Quizno’s—was arranged by Westchester management company Drollinger Properties, which agreed to let the shuttle park there while crews move some power lines and make some adjustments to its customized carrier.

Inglewood Forum at 3900 W. Manchester Boulevard in Inglewood

Though the shuttle is scheduled to pass by Inglewood City Hall at about 8 a.m. on Saturday, space is limited and officials are encouraging the public to go straight to the party at the Forum, where the shuttle is expected to be parked briefly from about 9 a.m. to 9:30 a.m. “That will be the real public kickoff,” says Fabrick, noting that the city is anticipating a crowd of some 10,000 people and that Hollywood Park will be offering free parking starting at 4 a.m. (no overnight camping.) “There will be a formal program and astronauts and a band and color guard. And the shuttle is so big and high that you won’t need to be on the curb to have a great view of it.”

Crenshaw Boulevard between 54th Street and Leimert Boulevard

The shuttle is expected to pass by here between about 12:30 p.m. and 1:30 p.m. Saturday. Though outsiders are being discouraged due to a lack of parking, the area is expected to have one of the better vantage points for locals who can walk or bike there. “The shuttle is going to be completely on the north side of the center median, so the sidewalk on the south side will be open,” says Fabrick, “and locals should have a fantastic view.”

Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza, 3650 W. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard

Saturday’s second big celebration is scheduled for 1:30 p.m. This one will have a special show produced and directed by choreographer Debbie Allen; seating will be limited, with seats distributed by mall officials. Police anticipate a standing room only crowd of several thousand and have urged spectators to arrive early. The program is expected to last about an hour, but after the shuttle’s 2 p.m. scheduled arrival, crews will be spending another hour or so at the site adjusting the shuttle carrier for the next leg of the trip.

Bill Robertson Lane at Exposition Park

This will be where the shuttle turns toward the California Science Center on Saturday at approximately 8:30 p.m., and probably the last, best place to see Endeavour before it is installed at the Samuel Oschin Space Shuttle Display Pavilion. Viewers will be encouraged to gather at four parking lots north of MLK between Bill Robertson Lane and Vermont Avenue. Public transportation is available by bus and via the Expo Line light rail.

Endeavour’s grand opening will be October 30, with early access for science center members. Admission to the science center and the shuttle is free, but viewers are encouraged to obtain time tickets to reserve a space. (Click here for membership information and here for time ticketing.)

It will be housed in a museum hangar pending completion of its permanent home at the Samuel Oschin Air and Space Center, which is aiming for completion by 2018.

Posted 10/11/12

A blossoming of international goodwill

March 21, 2012

Cherry blossoms at Descanso Gardens in La Cañada Flintridge, where a festival will be held this weekend.

It’s cherry blossom time again, and not just in Washington, D.C.

Southern California will be showered with more delicate pink petals than ever this year, as the region helps observe the 100-year anniversary of a goodwill gesture that turned our nation’s capitol into a blossoming, seasonal Mecca—a 1912 gift from Tokyo of more than 3,000 ornamental cherry trees.

At least a dozen local Cherry Blossom festivals have been scheduled, and trees have been planted from Los Angeles’ Roosevelt High School to Griffith Park. Meanwhile, in May, about 18 saplings will be planted in the new 12-acre Civic Park that’s being developed between City Hall and the Music Center. Embracing the spirit of a century ago, the Japanese Consulate in Los Angeles helped coordinate the donation of most of the region’s new trees through non-profit groups.

“Cherry blossom trees are a living testament to the friendship between Japan and the United States,” says Jun Niimi, Consul General of Japan in Los Angeles.

Elegant and evanescent, Japanese cherry blossom trees, or sakura, are a beloved sign of spring in that country. Few experiences are as dreamlike as the traditional picnic under a cherry tree in full bloom, as leafless boughs create clouds of pale blossoms and petals float on the wind.

The trees took hold in this country early in the 20th century, after Eliza Scidmore, a Washington socialite and travel writer, experienced them in Japan during a trip with her diplomat brother, and returned in 1885 with the notion that they should be planted on reclaimed parkland along the Potomac River.

The National Park Service has the full history, but the shorter version is that for the next 20-plus years, she unsuccessfully lobbied five presidential administrations. Finally, after an official from the U.S. Department of Agriculture proved the trees could survive here, Scidmore caught the attention of First Lady Helen “Nellie” Taft, who had visited Japan while her husband was governor-general of the Philippines during the McKinley Administration. The First Lady got 90 cherry trees planted along the Potomac, then accepted a donation from the Japanese government for thousands more saplings. Although pests infested the first shipment, nearly causing a diplomatic incident, the Japanese followed up with a new donation, and 3,020 cherry trees arrived by rail in Washington,D.C., on March 26, 1912.

By the 1930s, Japan-U.S. tree exchanges had spread throughout the country. In 1933, Los Angeles papers reported that the Japanese Chamber of Commerce was “strengthening the bond of friendship between America and Japan” by seeding Griffith Park with 375 cherry trees.

In 1941, four of the Washington, D.C., trees were vandalized after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, but they generally remained a positive symbol. In fact, the largest stand in Los Angeles County was the result of international goodwill, albeit of the corporate variety. In 1990 and 2009, the Canare Corp., a Japan-based cable manufacturer, donated a total of more than 1,000 cherry trees to Los Angeles to plant at Lake Balboa in the Sepulveda Basin.

“They had an office in the San Fernando Valley and wanted to give back to the city,” recalls James Ward, who at the time was in charge of the maintenance division of the Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks. “They even sent some of us back to learn how the Japanese maintain the trees.”

The saplings being donated in Southern California this year have come mainly from two programs, one local, one national.

Locally, the Huntington Botanical Gardens in San Marino made about 1,000 cherry trees available earlier this year to cities and civic groups throughout the region; the trees were mostly of the “Pink Cloud” variety, a unique West Coast hybrid that appeared as a volunteer seedling at the gardens in the 1960s. Nationally, the National Arbor Day Foundation, American Forests, the Japanese Embassy and a variety of Japan-America organizations have joined in a Nationwide Cherry Blossom Tree Planting Initiative to plant some 2,000 more trees.

Of course, beauty has its price. Frank McDonough, botanical information consultant at the Los Angeles County Arboretum & Botanic Garden notes that, except for the Pink Clouds and a few other varieties, the trees aren’t a natural fit in toasty L.A..

“They’re terrible for the landscape, they’re heavy water users and if they don’t get the drainage they like, they’ll leave you.”

But he adds: “People like them—they’re sentimental. And they’re pretty spectacular while they’re here.”

The area's largest stand of cherry trees is at Lake Balboa in Van Nuys, seen here in an earlier year.

Posted 3/21/12

The Rock is a wrap—for now

March 10, 2012

After its 4:30 a.m arrival, The Rock was parked for a photo-op in front of Chris Burden's iconic "Urban Light."

As crowds cheered and a loudspeaker blared Queen’s “We Will Rock You,” the Rock rolled into the Los Angeles County Museum of Art just before dawn on Saturday morning, riding down Wilshire Boulevard in its massive red transport like a 340-ton beauty in the Rose Parade.

“Fantastic,” said LACMA Director Michael Govan, unable to stop smiling as the focal point of “Levitated Mass,” the museum’s latest permanent installation, paused in front of the museum.

“Yahoo!” applauded Govan’s 7-year-old daughter, who was dressed in a pink coat and hoisted high on his shoulders.

“Magnificent!” breathed Alexandra Thum, a West Hollywood product designer who had worked her way through the crowd to get a curbside view. “It’s just so great to be here and see all the community together.” Around them, several hundred onlookers cried “Bravo! Bravo!” under the antique street lamps of another iconic LACMA masterpiece, Chris Burden’s “Urban Light.”

The reception capped an 11-day trip across 22 cities and four counties for the boulder, a hunk of granite the size of a 2-story teardrop that, in the weeks ahead, will be affixed atop a concrete channel, creating the illusion that it is levitating overhead. The work by Nevada earth artist Michael Heizer is scheduled to open in spring or early summer. (The famously reclusive artist was not on hand Saturday, but is expected to be in Los Angeles for the piece’s assembly.)

Although The Rock, as it came to be known, is only one component in the installation, it instantly became a media event itself because of the novelty and engineering involved in its move from its Jurupa Valley quarry in Riverside County.

Progressing at a stately 5 miles per hour and parked by day to minimize traffic disruptions, it inspired a marriage proposal in Glen Avon and a citywide block party in Long Beach, gawker’s block in Diamond Bar and pajama-clad sightseers near Expositon Park. In Rowland Heights, an accountant came home to discover it outside his bedroom window. So many people posed next to it for photos that, perhaps inevitably, it became an Internet meme for a digital moment.

While many thrilled at the spectacle, some decried its estimated $10-million expense, which has been covered entirely by private donors. “I think they should have spent $10 million on art programs instead of this rock,” said Patrick Taylor, a security guard and father of two who lives near Exposition Park.

Overall, however, museum officials were pleasantly surprised at the public reaction, which included a wave of fresh awareness for LACMA.

“When this started, I thought it would be much more controversial,” said Govan. “You know, ‘Is it art? Is it not art?’ But people mostly have just been fascinated and appreciative. And so many have learned about the museum from this experience.”

On Friday night—or, more accurately, Saturday morning—that appreciation was out in full, only-in-L.A. glory as thousands pulled all-nighters for the last leg of The Rock’s journey, up Western Avenue and along Wilshire Boulevard’s famed Miracle Mile.

Onlookers on foot and on bicycle snapped photos and videos and narrated the boulder’s slow-speed progress on hundreds of cell phones. Dogs barked. Tourists jumped out of buses and cabs to investigate the commotion.

A tall man dressed as Jesus and a shorter person dressed as a unicorn posed for pictures. Comedians worked the crowd. (“Have you seen my dog? It’s a ROCK-weiler!”) Further back in the crowd, actress Sharon Lawrence (“NYPD Blue,” “Desperate Housewives”) kept a low profile with her physician husband.

When the boulder slowed to make the painstaking turn in front of the Wiltern Theatre, a man waving an American flag ran out into the intersection, whooping. When the transporter was forced to stop, waiting for a tow-truck to remove a Dodge illegally parked in front of a karaoke bar on Wilshire, a dazed-looking young woman leaped into the street and either fell or tried to crawl underneath it. Shaken crewmembers escorted her back to the sidewalk and issued her a stern warning.

But for the most part, the mood was festive and communal, and the boulder’s movers—many of whom had walked alongside the megalith for most of the 105-mile route—were ready to celebrate by 4:30 a.m., when the procession paused in front of “Urban Light” for its final paparazzi moment.

“I got blisters on three of my toes,” laughed crewman Joe Schofield of Emmert International, who said on Saturday that he had been on foot, watching the rock, for more than 75 miles of the journey. Separate work crews ran ahead at each stop to clear the path of utility lines and landscaping. Workers from Time Warner Cable said they had moved lines in some 90 locations.

“Everybody has been clapping and cheering and connecting,” said Emmert General Manager Mark Albrecht, noting that, aside from that one incident with the young woman and a couple of mauled palm trees, the delivery was almost miraculously free of hitches. Around him, hard-hatted workers humbly ducked their heads as Los Angeles County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky and Los Angeles City Councilman Tom LaBonge thanked them.

Meanwhile, a crush of spectators rushed to touch the shrink-wrapped megalith with their fingertips until the transporter was put into gear again for the last yards of its journey, finally disappearing behind a gate on Fairfax Avenue and Sixth Street at 5:03 a.m.

Putting the squeeze on Lap-Band ads

December 20, 2011

County supervisors squared off Tuesday with promoters of the Lap-Band, featured on billboards all over Southern California but drawing increasing attention from officials concerned that the publicity blitz is obscuring a wide range of medical dangers.

After a series of sharp exchanges with representatives of 1-800 GET THIN, supervisors approved a motion by Supervisors Mark Ridley-Thomas and Zev Yaroslavsky to bring greater scrutiny to Lap-Band marketing and procedures. They directed county staff to, among other things, “develop a plan to identify medical products and services that are being marketed in a dangerously misleading manner.”

The supervisors’ action comes after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recently sent letters to eight Southern California weight loss clinics and the 1-800 GET THIN marketing firm, warning that the company’s ubiquitous advertisements do not provide enough information about the risks of gastric bypass surgery or about the need to change eating behavior to lose weight over the long term.

“The FDA’s warnings raise significant concerns about the vulnerability of all County residents to these advertisements, particularly those who suffer from morbid obesity and wish to find a cure,” the motion said. “Medical experts and the FDA agree that the Lap-Band procedure is an aggressive treatment for obesity and should only be considered in clinically severe obesity cases.”

Robert Silverman, the president of 1-800 GET THIN, told supervisors that his firm is taking steps to bring its billboards and radio and TV spots into compliance with the FDA requirements. An attorney for the company said its surgery centers “have a better track record than just about anybody else.”

But supervisors were openly frustrated as they tried to find out more about how 1-800 GET THIN operates, in terms of referrals to clinics and responsibility for disclosing risks to potential clients.

“It’s been a long time since a witness or member of the public has come to that table and has obfuscated as consistently and persistently as you have today,” Yaroslavsky told the 1-800 GET THIN representatives. “I did not come here as a person who had any fundamental suspicion one way or the other about what you were doing. I leave here now thinking you are hiding something.”

The FDA’s action was prompted by Dr. Jonathan E. Fielding, the county’s top public health official, who last year asked the agency to investigate whether widespread Lap-Band promotion by 1-800 GET THIN was misleading.

The motion approved by supervisors Tuesday directed the Public Health Department to report back on what it is doing to get the word out about “safe and effective alternative methods to achieve and maintain a healthier weight.”

“There is no panacea for obesity, including the Lap-Band weight loss procedure,” the motion said. “However, there are proven strategies, when sustained over time, which can help people achieve a healthier weight, and decrease the risk for diabetes, heart disease and other chronic diseases.”

The motion also directed the County Counsel to provide legal options on steps the county could take to “ensure truthful advertising of aggressive obesity treatment procedures in unincorporated areas.” And it instructed the Chief Executive Office to pursue legislation to increase supervision and oversight of clinics that perform “aggressive and invasive obesity treatment cosmetic procedures.”

Posted 12/20/11

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink