Ready or not, here they come

August 26, 2011

With the clock ticking, a multi-agency panel in Los Angeles County has approved a plan to confront a “monumental” shift in California’s criminal justice system, one that forces the county to supervise thousands of newly released state inmates and incarcerate thousands more in its strained jail system.

With the clock ticking, a multi-agency panel in Los Angeles County has approved a plan to confront a “monumental” shift in California’s criminal justice system, one that forces the county to supervise thousands of newly released state inmates and incarcerate thousands more in its strained jail system.

Passage of the complex plan by the Community Corrections Partnership was required under a new state “realignment” law pushed by Gov. Jerry Brown and aimed at reducing California’s prison population while narrowing the state’s budget deficit. On Tuesday, the CCP’s plan goes before the Board of Supervisors, where it can only be rejected by a 4/5 vote.

Supervisors had lobbied hard against the state’s realignment law. They argued that Brown and the legislature were simply shifting the state’s burdens to California’s hard-pressed counties, with little regard for the financial implications or public safety risks. In fact, the state has committed to funding only the first year with a $112-million block grant and $8 million in start-up funds.

“This is going to be a tragedy for justice in our county,” CCP member Dist. Atty. Steve Cooley said Wednesday before casting the sole vote against the realignment implementation plan. “It’s predictable, it’s inevitable.”

The reality is that not even a unanimous rejection of the plan would have blocked or delayed implementation of the new law, known as AB 109.

Beginning October 1, the first flow of newly released state prisoners will begin arriving here and in counties across the state, where they’ll be supervised by local authorities rather than state parole officers. Under the state’s realignment program, only inmates convicted of non-violent, non-serious, non-sexual offenses will be placed under county supervision.

In Los Angeles County, that number is expected to hit 9,000 by June, swelling to as many as 15,000 in the second year. Taking the lead in their post-release supervision will be the county’s Probation Department, despite a highly publicized and contentious bid by Sheriff Lee Baca to assume that role.

Already, inmate files have begun arriving for pre-release review by probation, mental health and other designated officials. The goal is to make sure each parolee is provided with the necessary oversight and programs for rehabilitation. The process also is intended to weed out inmates who should have been exempted from the program because of serious or violent criminal histories or because they’d been earlier designated by corrections officials as “mentally disordered offenders.”

Inmates participating in “post-release community supervision,” who’ll be freed from 33 state prison locations, will be given $200, with orders to report to their designated locations within two business days. Despite the expressed fears of the Sheriff’s Department, the state says that only 2% of this type of inmate population has historically failed to show up for parole orientations within five days of their scheduled appearances.

Once they arrive at their assigned locations, a more thorough evaluation will take place, including risk assessments and “behavioral health screening.” Each supervised person will receive a “risk level determination” of Tier I (high), Tier II (medium) and Tier III (low).

Community-based organizations will be tapped to provide such services as substance abuse treatment, job training and other assessed needs. In the short term, because of time constraints, only organizations with existing county contracts will provide services. But longer term, the county will soon request proposals so more organizations can participate and specific service gaps can be filled.

One of the trickiest elements of the plan—described as a work in progress—will be to determine the precise mental health histories and needs of the new charges. Initial prisoner packets will include no detailed medical information. Talks are underway with state corrections officials to provide mental health records directly to the county’s Department of Mental Health but cost and confidentiality issues have yet to be resolved.

Post-release supervision represents just one component of the realignment challenges. The bill’s most controversial and daunting requirement changes the very nature of California’s county jails and, according to some criminal justice officials, poses the highest potential risk to public safety.

Under the legislation, defendants convicted of non-violent, non-serious, non-sexual crimes will no longer be sentenced to state prison unless they have prior violent or serious convictions or are required to register as sex offenders. Beginning in October, this class of defendants will be serving their time in county jail at an estimated rate of 7,000 a year. That means Sheriff Baca will have to further juggle and prioritize who stays behind bars and who’s freed on work release, GPS monitoring or other “community based alternatives.” Thousands of more beds, depending on funding, also would have to be opened at various jail facilities.

District attorney officials and others worry that, because of overcrowding, this new class of inmate will inevitably be sprung early and end up back on the streets, committing crimes at a time when, in the past, they’d be sitting in state prison cells.

In a section of the CCP implementation report titled “jail population management,” the authors state that the wholesale transfer of such responsibilities from the state to Los Angeles County “is monumental and will not only mark a challenge for the Sheriff’s Department but also the District Attorney, the Public Defender, the Probation Department, the Department of Mental Health, the Department of Health Services, the Superior Court, and all municipalities.”

But there are others who say they’re ready and anxious for the opportunity to help the returning inmates get fresh starts. For the past two months, representatives of community and faith-based groups have shown up at CCP meetings, where they’ve urged that a greater emphasis in the discussions be placed on rehabilitation rather than incarceration. And Wednesday was no exception.

As one speaker put it: “Let’s take a mess and turn it into a blessing.”

Posted 8/26/11

State prisoners, meet your minders

July 27, 2011

After a rare public tussle between two powerful local criminal justice agencies, the Board of Supervisors has unanimously picked the Los Angeles County Probation Department to oversee thousands of freed California prisoners who, as part of the governor’s budget plan, will no longer be charges of the state.

After a rare public tussle between two powerful local criminal justice agencies, the Board of Supervisors has unanimously picked the Los Angeles County Probation Department to oversee thousands of freed California prisoners who, as part of the governor’s budget plan, will no longer be charges of the state.

Chief Probation Officer Donald Blevins was given the nod over Sheriff Lee Baca, who had forcefully argued that his department was better suited to monitor an estimated 8,000 inmates who’ll be heading back to the streets of Los Angeles County during a nine-month period.

Critics of Baca’s proposal argued that such sweeping new duties would create public confusion over the mission of a department charged largely with suppressing crimes, not rehabilitating those who commit them. In Los Angeles and throughout the state, that job traditionally has been the responsibility of probation and parole agencies.

The board’s decision on Tuesday was based on a motion by Supervisors Michael D. Antonovich and Don Knabe, who noted that the Probation Department “has been providing supervision and rehabilitative services to adult probationers for over a century.” For that reason, they said, the agency has the kind of infrastructure and expertise that makes it best qualified to run the so-called “post-release community supervision program.” But the supervisors also called for a role for the Sheriff’s Department in identifying and, when necessary, apprehending high-risk parolees in the program.

The truth is that county officials at all levels wish they’d never had to confront the issue in the first place. Earlier this year, they argued strongly against being forced to take responsibility for the freed inmates, a key facet of Gov. Jerry Brown’s “realignment” budget strategy to save money and reduce prison overcrowding. Faced with the county’s fears about funding and strains on a local jail system already tearing at the seams, the state agreed to pay for the first year but has yet to fulfill its promises for funding beyond that.

The ex-inmates, whose releases are scheduled to begin October 1, are known as “non, non, nons”—meaning non-violent, non-serious, non-sex offenders. Under a new state law, those who violate the terms of their release will no longer be returned to state prisons. With few exceptions, they’ll serve a maximum of 180 days in county jails.

That same law also mandates that counties create an operational plan—including staffing, budget needs and re-entry services—through new multi-agency Community Corrections Partnerships. In L.A. County, the CCP will submit a plan to the Board of Supervisors for approval in August, one that is likely to include a role for the Sheriff’s Department.

Indeed, during Tuesday’s meeting Baca made clear that his department would not be relegated to the margins. “When it comes to managing high-risk parolees,” he said, “I’m not going to ask the chief probation officer for permission. I’m just going to do it.”

Obviously irritated, Baca also criticized Blevins for statements in a report to the chief executive officer in which he “literally had kind of drawn a moat around his department and looks upon me and my department as some kind of threat to the traditions of rehabilitation when, in fact, we are at the forefront of rehabilitation for parolees.”

During the meeting, Blevins, who chairs the county’ CCP, did not address Baca’s comments. But he later told the Daily News that the Sheriff’s Department would have a role in the oversight of the soon-to-arrive ex-inmates, albeit a limited one.

“Our original plan,” Blevins was quoted as saying, “was for absconders or individuals who have been working with probation but need a higher level or more intensive supervision, we would ask [the sheriff’s] assistance on those kinds of cases…The sheriff has indicated they are 24/7 and they can provide those kinds of services.”

Posted 7/27/11

The sheriff vs. the probation chief

July 12, 2011

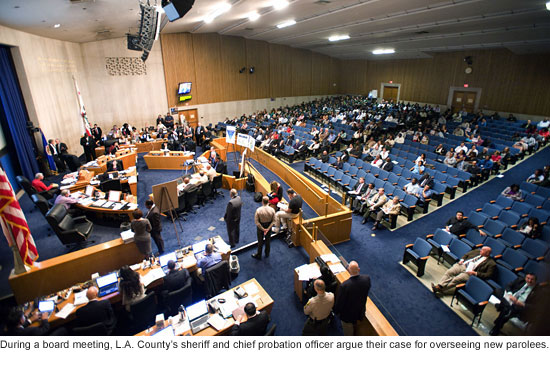

Two of Los Angeles’ most powerful criminal justice agencies faced off Tuesday during an extraordinary meeting of the Board of Supervisors, each arguing that they’d be better equipped to handle the surge of parolees who’ll soon be flowing into the county as a result of the state’s budget crisis.

Two of Los Angeles’ most powerful criminal justice agencies faced off Tuesday during an extraordinary meeting of the Board of Supervisors, each arguing that they’d be better equipped to handle the surge of parolees who’ll soon be flowing into the county as a result of the state’s budget crisis.

Under Gov. Brown’s “realignment” spending plan, California’s counties are being given responsibility for overseeing thousands of low-level state prison inmates who will be released to ease prison overcrowding and to save money. Although the state has agreed to provide funding to the counties for the first year, there are no guarantees beyond that.

Virtually everywhere else in the state, county probation departments have been tasked with these new duties, which are similar to those they already perform. But in Los Angeles, Sheriff Lee Baca has offered a novel and controversial proposal, contending that the public safety mandate of his department should be broadened to include the rehabilitative work of parole supervision.

On Tuesday, Baca took on Los Angeles County’s Chief Probation Officer Donald Blevins, who argued that his agency is not only more qualified to oversee the new parolees but that it can do so at a better price for taxpayers. The Board of Supervisors’ hearing room was crowded largely with Probation Department supporters.

The supervisors, who had strongly opposed Brown’s realignment proposal, challenged the two agency leaders to defend the content and cost of their proposals. Some expressed concerns that neither department—both of which have come under federal scrutiny for facets of their operations—could deliver on its promises. Several supervisors suggested that a hybrid of the two agencies should be considered. In the end, the board asked the Chief Executive Office to report back with an analysis of the competing proposals.

Critics of Baca’s bid contend that the Sheriff’s Department has no institutional expertise in overseeing parolees, a job more akin to social work because of its emphasis on reintegrating ex-prisoners into society. But the sheriff pointed to his record as a leading advocate for inmate rehabilitation and his department’s success in working with community-based re-entry programs.

“My department has the largest education-based incarceration program in the nation,” he said.

At the same time, Baca argued that the reach of his department could help protect the public from problems that might arise from such a large number of former inmates suddenly returning to live in Los Angeles County.

“This is a seven-day-a-week, 24-hour-a-day problem, and therefore resources must be dedicated to ensure that felons in the system understand we have the capacity to supervise them any time, any place, any time relative to the week,” Baca said.

Chief Probation Officer Blevins, for his part, acknowledged that his department has been plagued by problems in its juvenile camps. But he emphasized that it has an excellent record in supervising adults, many of whom are ex-felons and account for more than 70% of the department’s workload.

“We have a proven track record of working with this population,” Blevins said. Moreover, he said, the Probation Department could better comply with a legal mandate encompassed in the state legislation requiring the county to use “evidence-based” practices to reduce recidivism among state parolees. One probation program for probationers aged 18-25 at a county day reporting center has cut recidivism from 39% to less than 22%, he said.

The Probation Department’s plan, he said, “does not focus on suppression and incarceration over rehabilitation…It does not complicate and confuse the clients in terms of the roles and responsibilities of officers. It does not require building, learning and training to a brand new infrastructure that potentially can take years to implement and operate efficiently.”

Although the supervisors did not vote on the matter, several seemed openly wary of Baca’s plan, especially given its higher one-year cost estimate–$37 million versus $28 million for the Probation Department.

Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, for one, suggested that the board might not even be considering Baca’s proposal were it not for his reputation as one of law enforcement’s most forward-thinking figures.

“You’re unique, Lee,” the supervisor said told the sheriff. “The only reason this has been given the time of day is because you’re proposing it. If this had come from just about anybody else in law enforcement, I don’t think it would have been given serious consideration.”

Posted 7/12/11

The hills have eyes

June 30, 2011

They’ll be watching the fireworks, but not like the rest of us. For them, it’s personal, a call to duty.

On this Fourth of July, the volunteers of Arson Watch once again will be positioning themselves throughout 185 square miles of the Santa Monica Mountains, keeping an eye out for illegal fireworks and holiday revelers who could spark fires in the tinder-dry hills.

“We don’t want a great family holiday to turn into an out-of-control, raging nightmare,” says Sharon Donaldson, public information for the group, which works hand-in-hand with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department.

Like others in the group, Donaldson says that she and her husband joined Arson Watch after a brush with flames themselves. In their case, the “Old Topanga Fire” of 1993 blazed dangerously close to their home while they were vacationing in Hawaii. They watched the whole thing unfold on CNN.

“It was the worst feeling in the world. It was horrifying,” she says. “You’re feeling totally helpless, watching your neighbors’ houses in flames.”

The group was founded in 1982 by the late actor Buddy Ebsen after the “Dayton Canyon Fire” torched his neighbors’ homes and gravely threatened his family and ranch. When he learned that the inferno was arson, he sprung into action. Along with his daughter Cathy, he aggressively recruited his neighbors to help local authorities prevent future fires, forming the original nucleus of Arson Watch.

Today, Arson Watch is staffed by 112 volunteers who log 2,500 to 4,000 hours per year. They assist the Sheriff’s Department at the Lost Hills/Malibu station by patrolling, talking to the public and serving as witnesses. They represent an early warning system in case of an actual fire, notifying fire officials who can try to contain it.

“We are the eyes and the ears of the Santa Monica Mountains when there is fire weather,” says Donaldson, who adds that their presence alone can serve as a deterrent.

While there’s no way to definitely gauge the deterrence effect of Arson Watch, its members note that there has been only one major fire started in the Topanga/Malibu area since the group was launched—the fatal blaze that raced through Donaldson’s neighborhood.

Independence Day, with so many people in party mode, poses some unique and tricky challenges for the volunteers.

For example, on one recent July 4th, an Arson Watch volunteer was alone in remote Tuna Canyon, walking on a fire road where the public is not permitted. There, winds can quickly whip a spark into a wall of flame. The volunteer was soon overwhelmed by a crowd of young people clambering up a bluff to throw an impromptu “rave,” says Donaldson.

She remembers hearing his concerned voice over their two-way radios. Hundreds of partiers were upon him, carrying fireworks and smoking. Refusing his pleas to leave, he enlisted help from the sheriffs, who broke up the dangerous celebration.

According to data from the National Fire Prevention Association, illegal fireworks caused an estimated 18,000 reported fires in 2009, including 1,300 structure fires, 400 vehicle fires and 16,300 “outdoor and other” fires. In all, they caused a reported $38 million in property damage and 30 reported injuries.

The risk is especially high in wildfire-prone regions, such as the Santa Monica and San Gabriel mountains. The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection has already recorded 33 major wildfires in 2011. About two weeks ago, Governor Jerry Brown issued an executive order devoting more resources to fighting and preventing the fires.

This 4th, remember that all fireworks are illegal in L.A. City, unincorporated parts of L.A. County, and in other cities including Pasadena and Long Beach. A few cities such as Gardena and Alhambra permit “safe-and-sane” fireworks–but there are restrictions on who, where, and when they can be used.

The penalties for illegal fireworks can be severe. Small amounts are confiscated and may incur fines, says Sergeant Mark Bock of L.A. County Sheriff’s Malibu/Lost Hills Station. However, aerial fireworks and others like M-80s are considered explosives, and can bring felony charges. If the fireworks injure or kill anyone, perpetrators can be charged with serious felonies like mayhem, manslaughter, or even murder.

Donaldson recommends leaving fireworks to the pros, and suggests contacting law enforcement if you see people lighting them.

“It’s illegal, number one, and it’s not worth it,” she said. “There are amazing fireworks shows everywhere; you can go see these professional shows and not put lives at risk.”

She and her fellow Arson Watchers will be in the mountains this weekend to make sure people heed that advice.

Posted 6/30/11

Budging on the budget

March 2, 2011

We spoke—and the governor listened.

This week, Gov. Brown’s office announced that he’d scaled back one of the most onerous facets of his “realignment” plan to erase the state’s $26 billion deficit. Responding to concerns and criticisms of county leaders and law enforcement officials across the state, Brown significantly shrank the numbers of state prisoners and parolees he’d planned on putting under the management of California’s counties.

And that’s good news for a couple reasons.

First, our local criminal system already is bursting at the seams. Our jails are overcrowded and we simply don’t have the kind of staffing—or the money—needed to supervise the huge numbers of parolees with which the governor wanted to saddle us. The Board of Supervisors, Sheriff Lee Baca and District Atty. Steve Cooley had made this abundantly clear to Sacramento.

And second, Brown’s concession shows he’s willing to compromise in the face of compelling evidence—a refreshing development in an age of political brinksmanship. His change of course suggests that his overtures to us are sincerely intended to ensure that his budget plan doesn’t just undermine another branch of government—in our case, L.A. County.

Still, this is just a beginning. The governor’s budget remains a work in progress. And with the clock ticking, there are a number of other areas that must be addressed immediately.

Of particular concern is the question of how Brown’s realigned services would be funded down the road. Under his current plan, he’s banking on the public to pick up the tab for five years by voting to approve $5.9 billion in tax extensions. But what happens after that, assuming voters even get on board?

Currently, there are no airtight guarantees that the state’s counties would get the necessary funding for such realigned programs as foster care, substance abuse, mental health, adult parole and the incarceration of inmates formerly held in state prisons. Along these same lines, there also are no protections for counties should they face rising costs for new or unanticipated federal program requirements.

My colleagues and I believe that only a constitutionally-guaranteed stream of revenue can ensure that these programs do not break the county’s bank in five years when the voter-approved tax extensions would be set to expire. Although the Brown Administration has drafted language for a constitutional amendment, it remains thin on details, failing to provide the kind of certainties needed by the state’s counties. We’re currently in talks to remedy this situation.

I appreciate the enormity of the fiscal challenges inherited by Gov. Brown, and I applaud his focus in confronting them. I know that this business of slashing California’s crippling shortfall is a serious one, with impacts that will be felt for years to come.

That’s why it’s essential we do not replace old problems with new ones.

Posted 3/2/11

Budget plan a red flag

February 4, 2011

The Assembly Budget Committee held a special hearing in Los Angeles Friday on a key facet of Gov. Brown’s plan to eliminate California’s crippling deficit. Here is the testimony I provided on the governor’s “realignment” proposal.

***

Welcome to our Hall of Administration and our board room, and we thank you for undertaking this hearing to discuss an issue that has our county and counties throughout the state extremely concerned. That issue is “realignment.”

Welcome to our Hall of Administration and our board room, and we thank you for undertaking this hearing to discuss an issue that has our county and counties throughout the state extremely concerned. That issue is “realignment.”

We recognize that the State of California has a budgetary tiger by the tail in the $28 billion deficit it faces. All of us appreciate the challenges being faced, and all of us welcome the Governor’s candid and transparent discussion of the magnitude of the crisis and its implications for the future. Los Angeles County—which, by all accounts, has managed its fiscal affairs as prudently as any major local government in California—understands what it takes to balance a budget.

Our County has publicly and privately conveyed to State officials, including the Governor himself, that as distasteful as the proposed cuts are, we are prepared to equitably share in the burden of those cuts—or, more appropriately, to ask the citizens who rely on county services to share in the burden of those cuts. The $12.5 billion in cuts will fall very heavily on human services, and California counties are the primary deliverer of such services in the State. We are anxious and prepared to work with both the Governor and the Legislature to help address this crisis.

Realignment is another matter, however. While we are prepared to work with the State on creating a realignment proposal that works for both of us, realignment is one of those concepts that sounds great in theory, but hasn’t always and won’t always work out in practice. The devil is always in the details. You certainly understand our wariness.

To put it simply: If the state proposes to save money by shifting both program responsibilities and the funding for them to counties, where will the savings be? Can it really be that local governments are so much more efficient that citizens will receive the same or higher levels of public service at substantially reduced cost?

If we are not careful, realignment will be less a swap of services and revenues to pay for them, and more a dumping of costly criminal justice and human services from the State’s books to the county’s books, the end result of which will be only to shift the huge deficits that the State has been incurring to counties which can afford them even less.

Proponents of realignment argue that it will restore power, flexibility and discretion to counties over their own finances. They assert that local governments and their constituencies will be free to choose whether to fund existing programs. This is simply not true. Most health and human service programs and their funding levels are already set by federal and state law for counties to administer with little or no discretion. Unless these constraints are lifted, this principal benefit of realignment will never be realized. And, lifting those constraints opens up an entirely different kind of debate over the equity and adequacy of the services that counties provide.

As to control over our own finances—this, too, is not true. Proposition 13 severely limited local governments’ ability to generate revenue by rolling back and capping local property assessments and tax rates. The problem has only grown more acute in the ensuing decades as the Legislature and voters have imposed new constraints and restrictions, most recently in adopting Proposition 26 last November, which sharply limits local fees. Any suggestion that Counties will have the ability to raise taxes or fees for services we may choose to provide—above what the state pays us for—is simply disingenuous.

To pay for realignment, the Governor has proposed a five-year extension of expiring tax revenues, subject to voter approval (and it is not clear that these revenues will be sufficient to pay for realignment). When asked what would happen in Year 6, the Governor said he’s hoping the economy will bounce back by then. Revenues fluctuate, and in fact, it’s a rule we all live by in government that during an economic downturn, when our people need services most, we have the fewest resources available to us. Hoping the economy will turn around in five years is simply not enough—we need a permanent, dedicated and stable revenue source if we are to take over these programs.

Let’s walk through a couple of examples. The realignment proposal calls on counties to take responsibility for jailing state parole violators and so-called “low level offenders.” As you know, Los Angeles County’s jails are overcrowded now. A federal judge has been breathing down our neck to deal with this persistent constitutional problem. There is simply no capacity to house state inmates without having to release county prisoners to the streets of our communities. Moreover, even if we did have the capacity, what makes the State think that we can absorb the cost of this added burden when the State can’t handle it now? It simply looks like shifting a bad debt from the State’s books to the counties’ books.

Another criminal justice proposal is to have probation take over the supervision of some parolees. Our staffing requirements for such a shift could be as high as at least 600 persons. Is the State prepared to pay us dollar for dollar what it will cost us to take over this job? Keep in mind that your parole officers are public safety officers who are entitled to a public safety pension. Our Probation officers are not. Even worse, in its infinite wisdom, the State gave its parole officers the 3% at 50 pension benefit which is breaking the back of many pension systems around the state. We did not. Are we expected to hire the state’s parole officers to handle this new responsibility at salaries and pensions that we don’t currently provide our own employees? As our District Attorney recently wrote, the budget proposal in the area of Corrections and Rehabilitation “will wreak havoc on Los Angeles County’s criminal justice system.”

Of the programs being proposed for Realignment, the biggest one in dollar terms is Foster Care and Child Welfare Services. Foster Care is a federal entitlement that requires us to provide services no matter how high the caseload. As you know, we are currently operating under a carefully negotiated waiver that provides not only a growth factor, but also flexibility on how to spend funds. Our CEO estimates that we would receive a fixed annual amount of $557 million to administer these programs. However, caseloads won’t remain fixed. It doesn’t take a mathematician to realize that rising caseloads with no growth factor for a program of this magnitude is a recipe for disaster. As it is, since the 1991 Realignment, we have absorbed significant cost increases in these programs due to unanticipated Federal licensing and monitoring requirements.

Where do we go from here? I have an abiding concern that the realignment proposals are not fully baked. To approve these proposals in the next 30 days, when consensus has not developed around them in years, is unrealistic and dangerous. Doing so will inevitably lead to a plethora of unintended consequences that will largely fall on us, not on the State.

The three basic principles that should guide us any realignment scheme going forward are: counties should not be net revenue losers; it should accurately and thoroughly scope out the current costs of each programmatic shift; and it should constitutionally guarantee a revenue stream that is sufficient to sustain the programmatic shift, not only for the next five years, but beyond, when the temporary taxes, if approved by the voters, expire. Anything short of that would wrap a millstone of fiscal insolvency around the necks of every one of California’s 58 counties.

Posted 2/4/11

Our new man in Sacramento

February 2, 2011

For more than a decade, Los Angeles County’s point man in Sacramento has been one of the oldest hands in the state capitol. When Dan Wall announced his retirement late last year as the top lobbyist for the county, he was capping a 37-year resume that dates to Ronald Reagan’s gubernatorial administration. Wall isn’t joking when he says he’s been lobbying since the first time Jerry Brown was governor.

So filling his shoes was no easy task, says Assistant Chief Executive Officer Ryan Alsop. “We searched for months and months.” And Alsop found his man just in time for a budget season that promises to be of historic importance.

So filling his shoes was no easy task, says Assistant Chief Executive Officer Ryan Alsop. “We searched for months and months.” And Alsop found his man just in time for a budget season that promises to be of historic importance.

Alan Fernandes, come on down.

Fernandes, a 36-year-old lawyer and father of two from Davis, comes to the county from the well-known Sacramento law firm of Nielsen, Merksamer, where he has represented public sector clients for nearly 10 years.

With a bachelor’s degree in political science from UC Davis and his law degree from the McGeorge School of Law at University of the Pacific, he is currently the lobbyist for San Diego, Riverside, Contra Costa and Marin counties. He also has served on the Business and Economic Development Commission for the City of Davis, where he not only helped turn the city’s collection of rare and antique bicycles into the California Bicycle Museum, but also helped the city land the formerly New Jersey-based U.S. Bicycling Hall of Fame.

“Alan will be a great asset to the county in Sacramento,” said Alsop, who lauded Fernandes’ “honesty, knowledge, great work ethic and communications skill.”

And he’s going to need every ounce of that talent.

With California facing a $25.4 billion budget gap, Gov. Jerry Brown has proposed transferring the cost of many services from the state government to the counties, offering local governments more autonomy, but also potentially leaving them with much greater financial obligations that might not be underwritten in the long term.

Los Angeles County, for example, has estimated that Brown’s realignment plan could force it to absorb many millions of dollars in new costs and overwhelm the county’s already over-crowded jail system.

“I think we’re at a point where the restructuring of the state and local relationship is needed,” Fernandes said, speaking by phone between capitol meetings. “If it’s done right, it can actually serve the residents of California a lot better. But if done wrong, it could actually set us back even further—if that’s even imaginable.”

Fernandes called the most recent election “one of the most important in California since Proposition 13. “The results are going to put us in situations via realignment that could restructure government,” he said. “I applied for this job because I want to be a part of that.”

Fernandes called the most recent election “one of the most important in California since Proposition 13. “The results are going to put us in situations via realignment that could restructure government,” he said. “I applied for this job because I want to be a part of that.”

But, he added, he also applied because Los Angeles County is in a class by itself as a player in Sacramento. “Los Angeles is a third of the state, at least.”

That’s high praise coming from a Northern Californian. In the interest of full disclosure, however, Fernandes did admit one potentially serious conflict:

“I’m going to be completely up-front,” he confessed, laughing. “I’m a big San Francisco Giants fan.”

The appointment to the $175,000 a year post is expected to become official on February 10. After a transitional period, Wall, 64, will finally retire.

“I have projects,” said Wall, who, in true county fashion, lives in unincorporated Sacramento County. “I have a 1961 Triumph TR 3, a little red sports car, and I’m going to put that in working order. I’m going to do a little wine cellar at home because I like wine. I want to play the guitar. And we want to go to Italy, my wife and I. I think after 37 years working in this process, it’s time for a little change of view.”

Brown’s budget painful but “real”

January 11, 2011

Crunching the numbers in Gov. Jerry Brown’s proposed budget, Los Angeles County officials are bracing for deep cuts in services and potentially many millions of dollars in less visible costs.

An executive summary of the potential impacts shows that a $1.5 billion statewide cut in the CalWorks welfare program could trim the program by $450 million in Los Angeles County, spelling the loss of benefits for some 37,000 families here. That, in turn, could create new demands on the county’s general relief program, leading to additional costs in an already strained county budget.

Meanwhile, the county Department of Health Services stands to lose some $20 million if a proposed $1.7 billion in cuts, including reductions in payments to providers, are made to the state’s Medi-Cal program. Those cuts would pose challenges for the county’s perennially deficit-plagued health department budget and contribute to “some serious problems in our provision of health care here in L.A. County,” Chief Executive Officer William T Fujioka told supervisors on Tuesday.

The executive summary of potential budget impacts also outlined what’s coming the county’s way under “realignment,” in which responsibility for many programs would shift from the state to the local level.

For one thing, the county’s Probation Department would assume responsibility for 30,000 or more “violent and serious” state parolees, including sexual predators, at an additional cost of $185.3 million—excluding the cost of hiring new staff and related expenses, Fujioka said. County jails also would absorb 13,550 convicted felons now in state custody—nonviolent offenders without sex crimes convictions—at a potential cost of more than $450 million. Other passed-along expenses would come in areas ranging from child welfare and foster care ($557 million) to court security ($132.5 million.)

“What is of serious concern…is whether or not we have sufficient funding to maintain the current level of services that will be sent from the state,” Fujioka told supervisors. “If these services come to us without the necessary revenue, it puts a burden on our already… severely challenged programs and services.”

His remarks echoed comments by Supervisors Zev Yaroslavsky and Gloria Molina, whose Op-Ed piece this week in the Los Angeles Times argued for a “financially sustainable” proposal that would allow local governments to help the state through its crisis.

Yaroslavsky was attending a funeral Tuesday morning and did not attend the board meeting. Molina used the occasion to forcefully call on county officials to enter into a true partnership with the state and find constructive ways to achieve the inevitable cuts.

“If you aren’t part of the solution then get the hell out of the way,” Molina said. “Nobody’s going to listen to a bunch of moaners and whiners and we in L.A. County shouldn’t do that.”

“Crying crocodile tears,” she said, “is not going to impress them [in Sacramento].”

The governor’s budget hinges on voter approval of a proposed June ballot initiative that would extend a 1% sales tax and a .5% vehicle license fee for five years in order to fund the programs that would become county responsibilities under realignment. At the end of five years, the state would pick up the funding responsibility, according to the county’s budget impact report.

But Fujioka told supervisors that passage of the ballot initiatives is far from assured. “Extending the taxes and fees is not a given…That is going to be a very difficult request to get through the state Legislature and also through the electorate.”

Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich criticized the governor, arguing that the proposed budget dodged the necessity of reforming state spending patterns.

“There are dollars that are being generated but they’re not being allocated to appropriate areas,” he said. “And then to get rid of their irresponsibilities by shifting it to the cities and counties without any stable source of long term funding makes no sense.”

“I was expecting the governor to be bold in addressing these issues,” Antonovich said, “instead of basically doing what Arnold Schwarzenegger had done.”

But Molina praised the governor for getting the budget out early and for letting the county—along with all Californians—know how much pain is in store as the state seeks to climb out of a profound economic “ditch.”

“The governor has put it squarely in front of us,” Molina said. “Here’s the numbers. Like ‘em or not, they’re real.”

Posted 1/11/11

At the center of the budget storm

May 20, 2010

When Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger this month unveiled his admittedly “ugly” spending plan that would slash the safety net for the state’s poor, one man understood the implications better than most.

When Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger this month unveiled his admittedly “ugly” spending plan that would slash the safety net for the state’s poor, one man understood the implications better than most.

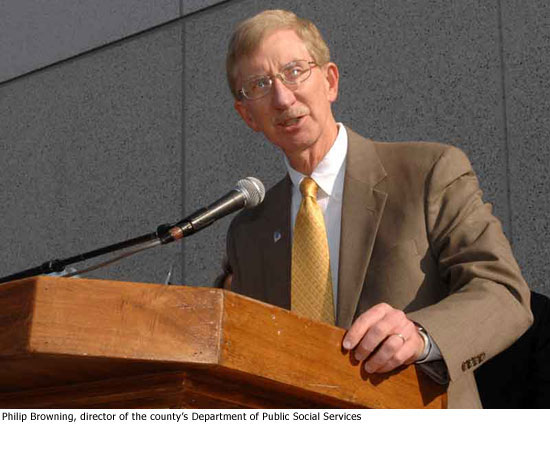

Philip Browning oversees Los Angeles County’s Department of Public Social Services, the largest such agency in the nation, serving more than 2 million people. Schwarzenegger’s proposed budget takes dead aim at the services his nearly 14,000 employees deliver, including in-home help for the disabled and the state’s welfare-to-work program.

Given the opportunity, here’s what Browning would respectfully tell the governor. “You need to visit one of our offices. Spend the day with one of our customers. Look at the people affected by your decisions. Until you see and experience their problems, you can’t appreciate your impact.”

Schwarzenegger, who has vowed not to raise taxes as a way to close California’s $20 billion deficit, has presented the legislature with a 2010-2011 budget that is unparalleled in the breadth of its proposed cuts to social programs. The largest single reduction would be the $1.6 billion CalWORKs welfare program, which provides an average of $500 a month to families and requires participants to eventually obtain jobs. Its elimination would make California the only state without a welfare-to-work program for low-income families with children.

Now the budget action will shift to California’s deeply partisan legislature, where Republicans have vowed to block tax increases and Democrats have insisted they will not, in the words of Senate leader Darrell Steinberg of Sacramento, “be a party to devastating children and families.”

This week, Democrats got ammunition from the non-partisan Legislative Analyst’s Office, which said Schwarzenegger’s proposed cuts to CalWORKs and other social programs should be rejected in favor of new fees and other less damaging approaches to replenish state coffers that have been drained by the faltering economy.

As Browning knows, the stakes in all of this are extraordinarily high for L.A. County, which is grappling with its own $500-million budget deficit. His department has estimated that if CalWORKs was eliminated, 320,940 children in 167,617 families would lose cash assistance. Financial responsibility then would be shifted to the county’s general relief program, costing the county an estimated $452 million annually—if just half of CalWORKs participants were deemed eligible. (Click here for an analysis by the county’s Chief Executive Office.)

And the fallout wouldn’t end there. More than 4,000 county employees who administer the CalWORKs program would suddenly find themselves without jobs, putting additional strains on county services at a time when CalWORKs’ client rolls already have swelled because of the recession. “There are very few empty seats in our waiting rooms,” Browning said.

Browning said he drove by one of his agency’s offices the other day and saw people lined up in the early morning drizzle. “They were standing out in the cold so they could be first in line to get inside a warm building, where they could apply for a benefit that is meager, at best.”

Many of these people, he said, represent the newly needy, who never pictured themselves applying for food stamps or benefits that the governor now wants to end. They’ve come in such large numbers, Browning said, that some of his front-line workers have had a hard time adjusting. “The workers identify more with participants today than ever before,”

Browning said. He said they tell him: “They look just like me. I feel so bad.”

To help them cope, Browning said he created an “emotional well-being class,” where workers can share their experiences and find support. He said he also created a “basic finance” class that teaches about “bankruptcy, foreclosure, all the terms that we are having to deal with.”

The imperative now, Browning said, is to communicate these realities to Sacramento.

“I have to make the best case possible about how human lives are going to be impacted by the decisions that politicians make in Sacramento,” Browning said. “They are far removed from the everyday trials and tribulations of these individuals. Some our legislators have taken the time to go on ride-alongs with us. They’ve seen the debilitation, they get it. But there are some who we can’t get to take that journey with us yet. They’re the ones we’re trying to show that what we’re doing is responsible, accountable and not overly generous.”

In recent weeks, he said, the agency has been videotaping people who desperately need the programs that are on the governor’s hit list, including In-Home Supportive Services, which has been targeted for significant cuts. The IHSS program pays a worker to provide basic care for qualifying seniors and others with disabilities so they can live independently.

“Without someone to take care of them at home,” Browning said, “I’m convinced they’d be institutionalized.”

He said the videos—one of an elderly disabled woman, the other of a severely handicapped child—would hopefully be shown during budget deliberations to give legislators a real-life understanding of the issues beyond the statistics.

He said the videos—one of an elderly disabled woman, the other of a severely handicapped child—would hopefully be shown during budget deliberations to give legislators a real-life understanding of the issues beyond the statistics.

Still, no matter how effective the strategy, Browning knows that difficult days lie ahead. He believes compromise will be reached in Sacramento to avert the worst-case scenarios but that state government simply has run out of gimmicks to balance the budget.

“All the smoke and mirrors have been used,” he said. “I think there are a lot of people who are going to be hurt.”

A lifeline for independence

Faced with the prospect of serious cuts to social services in the California budget, the L.A. County Department of Public Social Services has produced two videos showing the crucial role of one endangered program—In-Home Supportive Services, which helps seniors and others with disabling conditions avoid institutionalization.

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink