1.7 miles of good news on the 405

May 22, 2013

The 405 Project hits a major milestone as a new lane opens between the 10 and Santa Monica Boulevard.

There’s light at the end of the project. The 405 Project, buffeted by high-profile delays and escalating frustration levels among motorists and those who live and work around the construction zone, has a bit of good news to announce:

The first stretch of the 10-mile carpool lane at the heart of the $1 billion-plus improvement project is set to open this week.

Starting Friday, May 24, the new lane, running for 1.7 miles on the northbound 405 between the 10 Freeway and Santa Monica Boulevard, will be open to motorists. For now, everyone—not just carpoolers—will be allowed to drive in the lane, which expands the northbound freeway to six lanes.

According to a construction notice from Metro, the new lane will accomodate between 1,500 and 2,000 vehicles per hour.

The massive project, under construction since 2011, originally was set to be completely finished this year. But a series of problems—including complex utility relocations and shifting the location of Sepulveda Boulevard—has slowed work considerably and forced a rethinking of the schedule. Now officials have decided to open the project in phases, with Thursday’s lane-opening marking the first installment. A second, 1.4 mile stretch to Wilshire Boulevard will open next month, while the northernmost segment is expected to open later this year. The middle segment, where most of the delays have occurred, is slated to open in 2014.

The delays have prompted criticism from Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky and other elected officials, including U.S. Rep. Henry Waxman, who’s called for an investigation into why things are taking so long and asked Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood to do everything he can to expedite the project.

When complete, the Metro-Caltrans project will have widened the 405 to accommodate a new 10-mile northbound carpool lane, modernized and rebuilt three towering bridges and created a safer and smoother-flowing set of flyover ramps at Wilshire Boulevard.

Posted 5/21/13

Small step toward fixing a big problem

May 22, 2013

The Board of Supervisors this week gave the go-ahead for an immediate staff infusion to step up oversight of foster and group homes, as the county Department of Children and Family Services works to develop longer term, comprehensive strategies to correct long-running problems in foster care monitoring.

While no one contends that the seven new positions approved Tuesday would in themselves reverse years of breakdowns and concerns, the move was seen as a concrete step in the right direction.

“This is an attempt to do something about the problem by increasing the resources, human resources, that the department has to address this in a more pro-active and thorough manner,” said Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas.

Under questioning by Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, who proposed the staffing increase as part of a broader package of reforms approved last month, DCFS director Philip Browning said the unit responsible for such monitoring had lost 15 staffers over the past decade—a drop from 51 employees to 36.

“Frankly, staff cuts do have an impact,” he told supervisors.

He said the new positions in the department’s Out-of-Home Care Investigation Section “would assist us in ensuring that state-licensed foster homes and group homes are monitored to the same level as the foster family agencies.”

Browning emphasized that the move was not a “total solution,” and noted that broader solutions are still being developed.

According to a letter to supervisors from the county’s Chief Executive Office, the staffing expansion will enable “timely and comprehensive reviews” of allegations and incidents, and will make it possible to more quickly identify patterns that require county intervention.

The board’s action came following the disclosure of long-running allegations of impropriety within Teens Happy Homes, a foster family agency under contract to the county.

Posted 5/22/13

Prescription for a new jail?

May 22, 2013

Assistant Sheriff Terri McDonald says that addressing custody issues for mentally ill inmates is a top initiative.

Los Angeles County’s jail system has, in the words of Sheriff Lee Baca, become the nation’s largest de facto mental hospital. Thousands of inmates who need intensive treatment are posing huge medical, logistical and financial challenges inside and outside the lockup. The buildings that house nearly 19,000 inmates simply weren’t designed to cope with the realities of today’s inmate population in Los Angeles.

And no one is more aware of the problems looming on the edge of downtown than Assistant Sheriff Terri McDonald, who was recently hired as part of the sweeping reforms a blue-ribbon commission recommended to curb deputy brutality against inmates.

“It’s one of my top initiatives,” McDonald said of finding a way to house and treat mentally ill offenders. “It’s a complex social and criminal justice issue. If they’re going to be jailed, then it’s in the best interest of the county to design a jail that best meets their therapeutic needs.”

On Tuesday, the Board of Supervisors unanimously agreed with that assessment, taking the first steps in what could lead to the construction of an Integrated Inmate Treatment Center, which would house all mentally ill inmates, including those with co-occurring substance abuse disorders, for specialized treatment.

“I am open as a policymaker and as a taxpayer to doing something that costs money if it stands a chance of actually producing results and…not just warehousing people,” said Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, who authored the motion calling for an analysis of a stand-alone facility.

Yaroslavsky said it makes no sense to raze the archaic Men’s Central Jail downtown and build a proposed $1 billion replacement that essentially would serve the same function. “I just think that’s a colossal waste of money,” Yaroslavsky said. But construction of a separate facility to create badly needed mental health beds and treatment space would be “a game changer,” the supervisor said.

The board directed Vanir Construction Management, a county consultant already studying plans to replace Men’s Central Jail, to undertake a separate analysis of the mental health facility concept in conjunction with the Sheriff’s Department and the county’s health agencies.

Currently, according to McDonald, 2,500 inmates require mental health services. The number of intensive mental health treatment beds, she said, represents a quarter of what’s needed. What’s more, she said there’s a severe shortage of group treatment spaces to explore such issues with inmates as anger management, medication compliance and hygiene—“places to talk about their ability to be successful.”

Yaroslavsky and McDonald said the broader public would benefit, too. Studies show that recidivism drops among mentally ill/dually diagnosed inmates who receive intensive treatment. A separate facility would also open up more beds for the general inmate population; mentally ill inmates now are often placed alone in two-bunk cells, McDonald said.

What’s more, with the federal justice department monitoring the county’s management of mentally ill inmates—and the ever-present potential for lawsuits—the construction of a new facility would further demonstrate the county’s commitment to improving conditions for this growing and difficult population.

Earlier this year, a Sheriff’s Department study found that jailers were more likely to use force against mentally ill patients, who can be more disruptive and less compliant, requiring staff with more specialized training to avoid conflicts.

“Mentally ill inmates have a much more difficult time adjusting to a jail environment,” McDonald said. “They sometimes get paranoid and attack the staff or each other.”

By all accounts, the completion of a new downtown facility could be years away. So for now, McDonald said, she’s trying to come up with a “temporary solution” by reconfiguring existing space to free up more mental health beds and treatment areas.

“We’ve got to do something here,” she said. “Our mentally ill offenders need more out-of-cell treatment time and we need additional bed capacity.”

If approved, the Integrated Inmate Treatment Center would be built on the site of Men's Central Jail.

Posted 5/22/13

Remembering fallen heroes

May 21, 2013

Get summer off to a good start by taking a moment this Memorial Day to remember those who lost their lives serving in the U.S. military.

Various events are scheduled for Monday, May 27. Here are some of the options.

Canoga Park will hold its annual Memorial Day Parade and 5k Run/Walk in the San Fernando Valley and the 3rd Annual Walk for Warriors in West L.A. will benefit veterans experiencing difficulty returning to civilian life. Also in the Valley, the Mission Hills Neighborhood Council is sponsoring a Civil War reenactment and 21-gun salute to mark the occasion.

Some of the cemeteries across the county will be hosting solemn, traditional remembrances. Forest Lawn Cemetery in the Hollywood Hills will hold its annual observance. At Woodlawn Cemetery in Santa Monica, the 75th Annual Memorial Day Observance will feature a Condor Squadron fly-over and the unveiling of the design for a commemorative wall. For those who want to give something back this Memorial Day, the Santa Monica event needs volunteers to help meet and greet guests.

A full list of events and observances compiled by the county Department of Military and Veterans Affairs is here.

Posted 5/21/13

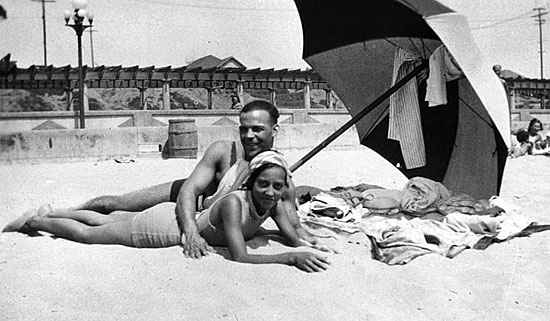

A surf pioneer gets his day in the sun

May 16, 2013

A new holiday celebrating the diversity of Southern California’s beach life has been quietly gathering momentum at the Santa Monica Pier.

Nick Gabaldón Day. The name may not be familiar now, but it’s about to get bigger, starting with an all-day event June 1 on one of Santa Monica’s most storied beaches.

Launched by a group of historians and surf enthusiasts with the support of Heal the Bay and other organizations, the event honors Nicolás Rolando Gabaldón, the first Southern California surfer known to be of African-American and Mexican extraction.

Gabaldón grew up in Santa Monica and surfed on a stretch of shore colloquially known as “The Inkwell” because it was one of the few beaches during the Jim Crow era on which black beachgoers were welcomed. He went on to surf in Malibu with some of the biggest names of the sport’s formative decades.

For years after his death in a 1951 surfing accident, he was all but forgotten, a casualty of the cultural myopia of a racially fraught era. But in recent years, he increasingly has become a rallying point for cultural historians, environmentalists, surfers, inner city groups and others who want the beaches to feel more inclusive.

Five years ago, the City of Santa Monica dedicated a plaque honoring his contribution to surfing, and at least two documentaries since then have focused on his story and the history of African-American surfers. Last year, Heal the Bay and the Santa Monica Conservancy partnered with black swimmers, surfers and divers to combine a coastal cleanup day with a lesson on Gabaldón and the history of The Inkwell, an experiment that led to this year’s more elaborate celebration.

The event, which starts with a paddle-out on the south side of the Santa Monica Pier, will include free surf lessons (click here for reservations), documentary screenings and a beach reception with Los Angeles County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas. Organizers—who include the Black Surfers Collective, the Santa Monica Conservancy, the Surf Bus Foundation, the California Historical Society and Ridley-Thomas’ office—say they are hoping it will lead to an official annual observance.

“Surfing has always been a multicultural activity, but we’ve been denied access through gates that are sometimes legal and sometimes not,” says Rick Blocker, a retired Leimert Park schoolteacher and founder of BlackSurfing.com, a web site that recognizes surfers of color.

Adds Meredith McCarthy, Heal the Bay’s program director: “It’s a way to bring people to the beach who may have never felt welcomed, and a way to start connecting to communities.”

Wayne King, 85, who knew Gabaldón as a Santa Monica High School surfing buddy, jokes that if his friend were still alive, “he’d never believe it—he was just an ordinary guy in the neighborhood.”

King himself was a child when his family moved to Santa Monica from Missouri in 1937. “We were in segregated schools and couldn’t go to school higher than sixth grade back there. My parents knew if we were to have any kind of a chance, we’d have to move to California.”

His father became a welder at Douglas Aircraft Co., King says, and the family settled near 19th Street and Delaware Avenue, in a neighborhood of mostly black and Latino families. King liked to swim, having learned while playing on rafts in the Mississippi River. The Gabaldóns—they were divorced, he says, and Nick lived with his African-American mother—lived a few blocks from the King house. Inevitably, the boys met on the sand.

Today, he notes, his old local beach is one of the swankiest on the Westside, situated between Bay and Bicknell streets just south of the Casa del Mar hotel. In those days, however, it was much narrower and rocky. Nonetheless, on weekends, the sand filled with African-American and Latino families, and the kids who were fortunate enough to live within walking distance developed a level of comfort there that their inland contemporaries didn’t share.

Over time, he and Gabaldón made friends with some white lifeguards who had noticed that the two boys enjoyed bodysurfing.

“They had one of those big, old-time wooden boards and asked us if we were interested, and they and a couple of other kids in the neighborhood, the Pilar brothers, taught us to board surf,” he remembers. It was “exhilarating”, he says, and eventually, he and Gabaldón bought their own boards and began looking for bigger waves to tackle, a challenge that drew the easygoing young black men into a culture that was dominated by white and Pacific Islander surfers.

It also forced Gabaldón to eventually buy a car, King says, because motorists on Pacific Coast Highway were so reluctant to pick up a black man. At least once, he says, Gabaldón told him he’d paddled all the way from Santa Monica to Malibu on his surfboard, a legendary trek that inspired the name of one of the documentaries about him, “12 Miles North: The Nick Gabaldón Story.”

“We were like a pair of flies in a bowl of buttermilk,” he laughs. “But we didn’t really get a hard time from other surfers. People who hang around the beach are a different breed—they might look at you funny at first, but once you got in the water, you were all the same.”

The two remained friends as Gabaldón joined the Navy, then returned home to attend Santa Monica City College. King recalls being on the beach the day his friend died.

“It was 1951, the first week of June,” King recalls. “He decided he wanted to shoot the pier, go in between the pilings. All of a sudden, this rogue wave came up and he disappeared.”

King, who now lives in Altadena, eventually became a 32-year City of Santa Monica maintenance worker. “I spent 11 or 12 years cleaning those beaches, and I never went back in the water,” he says now. “Seems like after Nick passed, I just lost interest.”

Others did not, however. After Surfer magazine did an article on black surfers that mentioned Gabaldón in the early 1980s, Blocker began questioning his Malibu surfing buddies.

“People said, ‘Oh, yeah, that black guy in the ‘40s and ‘50s? Yeah, he was here.’ Well, to me, that attitude seemed wrong. His story seemed to me like one that needed to be remembered.”

So, picking up where Surfer magazine had left off, Blocker began writing, and his research found its way to Alison Rose Jefferson, a Los Angeles historic preservation consultant and doctoral candidate in history at UC Santa Barbara.

Jefferson, who was researching race and the history of Southern California’s leisure spaces, had her own interest in Inkwell beach and the community around it. Her work, and that of Blocker, in turn, drew the attention of Heal the Bay, which last year involved Blocker in efforts to toughen pollution limits in the county’s municipal storm water permit.

Jefferson views the interest in Gabaldón as part of a broader move to reclaim history among groups who have felt left out. But, she adds, raising his profile through alliances like this one also broadens the influence of groups like Heal the Bay, and reminds African-Americans and Latinos throughout the region that they, too, have history with California’s coastline and a stake in what becomes of it.

“Nick Gabaldón was a quintessential Californian. He’s multi-ethnic, part of his family immigrated to this country, and he participated in the California dream, pursuing his passion,” she says. “And people of color want clean water, too.”

Posted 5/16/13

Orange crush

May 16, 2013

The Orange Line is feeling the squeeze. An immediate success upon its opening in 2005, ridership continues to surge on the San Fernando Valley’s dedicated busway, which runs from Woodland Hills and Chatsworth to North Hollywood. The line currently handles more than 30,000 passengers on an average weekday, making it the second busiest bus line in Los Angeles County. While that success is something to celebrate, elbow room is getting hard to come by.

“Yesterday it was pretty miserable,” said Mark Hill, who commutes between Sherman Oaks and downtown Los Angeles. “You had people letting the bus go because you could just not fit any more.”

Metro plans to relieve some pressure by adding additional service. Next week, the agency’s Board of Directors is expected to take action on an annual budget that includes $1.2 million for more midday buses on the Orange Line. More late night service was also added recently, and increased Saturday service is planned for late June.

Jon Hillmer, a 30-year veteran in Metro’s bus operations, said the popularity is due to the line’s speed and convenience.

“It offers rail-like service on rubber tires,” Hillmer said. “People board at stations, wait on platforms and pay their fares at machines.”

The line also provides important connections to other transit options. At Chatsworth station, it connects to Metrolink’s service to Ventura County. At the North Hollywood station, it connects to the Red Line subway, which provides access to Hollywood, downtown L.A. and the rest of Metro’s rail system.

While improvements are planned to handle the growth in ridership during off-peak hours, rush hour is a different story. One additional bus trip will be squeezed onto the back end of the peak traffic period but, after that, the agency is just about maxed out on how many buses it can run at a time. Among other issues, the line is constrained at intersections with north-south roadways, which are managed by the city of Los Angeles’ Department of Transportation.

“Running buses every 4 minutes during rush hour is the best we can do under the current traffic configuration,” Hillmer said. “The city is reluctant to go below the 4-minute frequency level.”

Jonathan Hui, a spokesman for the city agency, said it allows buses to pass through the intersections every two minutes, but they only get special priority—early or longer green lights—every four minutes. That preferential treatment is important to keep the line moving swiftly.

“Not everybody can get the green at the same time,” Hui said. “The Orange Line is obviously important, but so are drivers, pedestrians and bicyclists.”

The two agencies are currently working on a solution to the problem. Hillmer said possibilities include sending two buses in tandem through intersections, or getting shorter but more frequent green lights to enable more buses to get through.

While the rush hour fixes remain a work in progress, adding extra buses during off-peak hours should be a big help to riders who crowd the Orange Line before and after rush hour.

“At 7:45 p.m., there are still a lot of people waiting, ” said Isabel Barbosa, who commutes from her home in Woodland Hills to downtown L.A. Even at 8:30 p.m., “it’s usually standing room only,” said another commuter, Ian Tudor.

Most of the current rider congestion occurs between the station at Sepulveda Boulevard and North Hollywood, but as last June’s extension of the line to Chatsworth matures, Hillmer expects more growth on the western end.

Ridership probably hasn’t even peaked for the year. The months of September and October, when students return to school, are typically the busiest. The extra riders should push the line’s numbers closer to those of Metro’s busiest bus line—the 720 Rapid, which runs between Commerce and Santa Monica on Wilshire Boulevard and averages about 40,000 riders each weekday.

Despite the ridership boom, Orange Line commuters like Mark Hill say they appreciate the smooth, fast ride the line offers—even when it’s standing room only.

“The buses are nicely appointed,” he said. “There’s plenty of stuff to hang on to.”

Posted 5/16/13

Hall of Justice gets the lead out

May 15, 2013

Inside the scaffolding-clad Hall of Justice, a massive lead paint clean-up is underway. Photo/Clark Construction

Los Angeles County’s legendary Hall of Justice has had its share of dangerous inhabitants over the years. Now you can add one more to the list: lead-based paint.

The 1920s-era red oxide paint, containing as much as 39% lead, was found when construction workers last summer uncovered painted steel beams that had previously been encased in concrete. Testing on the steel and surrounding concrete revealed higher-than-anticipated lead concentrations in both.

This week, the Board of Supervisors approved an ambitious, $6.45 million abatement effort that will require lead removal in more than 15,000 locations throughout the hall, which, since opening in 1925, has played host to some of Los Angeles’ most notorious figures, including Charles Manson, Sirhan Sirhan and Bugsy Siegel.

The unexpected discovery of the lead-painted structural steel came as workers were preparing to begin seismic reinforcement work on the imposing downtown structure, which has been closed since the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

“Absolutely, it’s a surprise,” said Greg Zinberg, project executive with Clark Construction, the contractor for the renovation. “We’ve had to re-strategize about how we’re approaching the project…We’re talking about thousands of hours of work.”

Areas within the building are being cordoned off to contain lead dust and workers must wear protective gear, including respirators and special suits, as they go about their tasks. A literal top-to-bottom scrubbing will be required to decontaminate the structure.

Even so, the project remains on schedule to finish up next year, with county departments, including the Sheriff’s Department and the District Attorney’s office, still on track to move in by early 2015. The lead abatement work itself is expected to wrap up by this October.

The funding for the lead removal comes from $16.9 million set aside in the project budget to cover unanticipated changes that crop up during the construction process. The overall budget for the project, which is being financed by long-term bonds, is $231.7 million.

This is not the building’s first brush with lead problems. When open fire escapes on two sides of the building were set to be cleaned out as part of the renovation project, workers found 4½-foot-high heaps of pigeon droppings on just about every floor, said James Kearns, the Public Works division head whose team is overseeing the project. Testing on the pigeon guano found lead as well as the more expected pathogens, resulting in an earlier $36,415 abatement effort.

The pigeons haven’t spared the surface of the building, either. Behind scaffolding, cleaning is now underway to restore the hall’s dingy grey exterior to its original white—the same color as nearby Los Angeles City Hall. But getting it done meant encountering decades-old droppings amid the colonnade of Romanesque columns along the building’s upper floors—“an interesting discovery,” as project executive Zinberg puts it.

As for the lead abatement, the latest twist in long-running efforts to bring the Hall of Justice back to life, workers are taking it all in stride. “Right now, we’re moving along and getting through it,” said Kearns, of Public Works. “It’s not an easy job but it’s all under control.”

For a look inside the building during an earlier phase in the construction process, click here.

Posted 5/15/13

Score two for mental health

May 14, 2013

Mutual fans: Stella March, center, with Laker star Metta World Peace. At left, county mental health director Marvin Southard and chief deputy Robin Kay. Photo/Los Angeles County

“How’s Kobe doing?”

The question came from 97-year-old Stella March, a stalwart Lakers fan for decades. And it was directed at someone she thought would know—Kobe Bryant’s teammate, Metta World Peace.

“He tried to fight through it, but he couldn’t,” Metta said of Bryant and the Achilles tendon he tore on the eve of this year’s NBA playoffs. “He’s doing better now,” he assured March.

“I felt badly for him,” she said softly.

Then March turned the conversation toward Metta—and her observations had nothing to do with hoops. “What you’re doing for the kids, it’s very meaningful,” she told him. As they talked, they held hands.

From outward appearances, these two—the tiny white-haired woman with the walker and the towering player with the muscular arms—might seem like an odd pairing for a meeting of the Board of Supervisors. But as both would be quick to tell you, you can’t judge what’s inside from the outside. For they share a mission that transcends their cultural and generational divide; both are committed to destigmatizing mental health problems and treatment. And in that respect, both are very much on their game.

March and MWP, as the former Ron Artest likes to be called, were honored Tuesday by the board to kick-off “Mental Health Awareness Month.”

March is widely recognized as one of the nation’s preeminent advocates for families whose lives have been touched by mental illness, a crusade she began in the late 1970s after her son, a UCLA student, was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Among other things, her efforts led to greater government and pharmaceutical research, ultimately helping to produce a new generation of medications. She also was the driving force behind building the National Alliance on Mental Illness and initiating its “StigmaBusters” program to combat inaccurate representations of mental illness in film, television, print and other media.

In those early years, she says, mental health treatment and research was so bad that many serious sufferers “were wandering around on the streets with nowhere to go. They were shunned and stigmatized as dirty street people.” With her organization’s help and support, she says, many of the severely afflicted “learned the basic skill of telling people how they recovered. Each one had a different story of recovery. It was fantastic.”

Metta World Peace understands the power of that message. Ever since he made headlines by thanking his therapist on network television after the Laker’s 7th-game championship victory in 2010, the once-troubled player has openly talked about his counseling for anger and family issues. In December of that year, he teamed up with the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health to produce a public service announcement aimed at encouraging young people to seek help. “Talk to somebody about it,” he says in the PSA. “I did. Take the first steps. Be a champion.”

Since then, he’s also made his pitch during high school assemblies here and across the country and has created a website called Limelight that promotes mental health treatment. A new public service announcement campaign between Metta World Peace and the county—called “Talk it Out”—was launched earlier this month and will continue throughout May.

Before their Tuesday appearance before the Board of Supervisors, March, a fan of MWP’s moves on and off the court, asked to meet him in a small conference room behind the board’s dais, where he was signing posters for the new campaign. Helped into the room by her daughter, Joella, and officials from the mental health department, March was greeted by the 6-foot-7 player with an embrace, as though she were the star. He then took a seat beside her so she wouldn’t have to strain looking up at him.

“Thank you for what you’ve done to help,” she told him. “We’ve got to keep advocating for people.”

She needn’t worry. As Metta World Peace told the audience in the board’s hearing room: “This is a lifetime work.”

Posted 5/14/13

Burning questions

May 9, 2013

When wind-driven flames tore through one of the Santa Monica Mountains’ most scenic canyons last week, hearts sank with visions of another city escape transformed into a smoldering moonscape.

Sycamore Canyon draws thousands of visitors every month with its gorgeous vistas, canopied trees and a network of trails suitable for everyone from strolling couples to hardcore hikers. So the big question was this: exactly how destructive was the fire that ignited near Newbury Park in the inland valley and didn’t stop until it reached the sea at Point Mugu State Park, about 30 miles north of Santa Monica?

Over the past couple of days, some answers—along with new questions—have emerged, as national and state parks experts have hit the charred ground to begin investigating the fallout from the only spring wildfire in anyone’s memory.

What they’ve found might be good news for people eager for a return to the trails but troublesome for the area’s wildlife, especially its birds, now in their prime nesting season. “Normally, with fall fires, that’s not going on,” said fire ecologist Marti Witter of the National Park Service. “There was probably a significant hit to bird populations.”

The rare early timing of the so-called Springs fire also has raised questions about the regenerative resilience of burned trees, which were in their spring growth period and already were challenged by drought conditions. Deciduous trees, such as the sycamores, had yet to begin moving nutrients from their leaves to their trunks, as they do during the late summer and fall months. Those leaves are now scorched or incinerated. At a minimum, experts predict that damaged trees could remain leafless and unsightly for months longer than if the blaze had erupted later in the year during the normal fire season, when subsequent wetter months help force new growth.

“People are going to be looking at a black landscape much longer than they normally would,” said Witter, of the park service’s Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area.

For now, the public won’t be seeing anything; officials have ordered a two-week closure of the Sycamore Canyon Trail area until an assessment of the potential dangers can be determined. A key player in that process is National Park Service plant ecologist John Tiszler, who, like Witter, also works in the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area. Earlier this week, he toured the popular lower canyon on behalf of Ventura County fire officials.

“Clearly, the vast majority of it burned,” Tiszler said. “I know people are very worried about this but I don’t think there’s any reason to think that a catastrophe has occurred.”

Tiszler said “the fickleness of the winds” had left some spots unscathed as the flames quickly shifted through the broad lower canyon beyond the undamaged Point Mugu campground. Those scattered green zones, he said, could provide refuge for displaced, nesting birds and such ground wildlife as lizards, which park service staffers are attempting to rescue. (Click here for a satellite image of the “burn scar.”)

Tiszler said that, in the lower canyon, he flagged only 15 sycamores and oaks that had the potential to fall along the fire-road trail. Only three or four of them, he said, should be taken down. But in the canyon’s upper, narrower passages, he said, the toll appears worse because of more intense flames and heat.

The staying power of all those affected trees could be tested in the days ahead, Tiszler said, when high winds are expected to whip through the area again. He also said a looser standard will be applied to damaged trees along hiking trails that don’t have gathering areas, where the public might linger and be at greater risk. “If there’s no person, car or picnic table,” he said, “then the potential of being a public hazard is much reduced.”

Tiszler also noted that trees in Sycamore Canyon had withstood a number of blazes over the decades, including the more devastating Green Meadow fire in 1993. “Trees are like alien beings from another planet,” he said. “They are so different from us, the way they heal themselves, what they tolerate.” He said trees can stand strong even with deep hollows burned into their core because their weight is borne by their outer rings.

Like many veteran hikers and naturalists, Ron Webster of the Sierra Club does not view flames as an enemy of Sycamore Canyon’s trails, a good number of which he helped cut years ago. “You know, it’s just fire. The place greens up and then we’re off again,” said Webster, who, at 78, still leads trail crews in the Santa Monica Mountains.

“Be sure to schedule hikes there in the spring. You’ll see wildflower displays like you won’t believe,” Webster said, noting that seeds have long been lying dormant under the deep chaparral that has been burned away.

Witter of the park service said she, too, has learned to put the area’s fires in perspective. A longtime Topanga resident, she remembers the destruction of property—and the uprooting of lives—from the wildfires two decades ago that cut a fiery path from the mountains around her neighborhood to the ocean’s edge in Malibu.

“Seeing all those burned homes, that was emotionally devastating,” Witter recalled. “This fire has changed the landscape, but it should come back.”

Fire hollowed out the core of this broken oak so its outer rings could no longer support its weight.

Posted 5/10/13