Attention thrift store shoppers

February 27, 2013

You don’t need to be a hip-hop enthusiast to go out and “pop some tags” at the thrift shop. And thanks to the L.A. County Board of Supervisors, that vintage velour jumpsuit and those used house slippers may be closer than you think.

The supervisors on Tuesday eased zoning restrictions on secondhand stores in unincorporated Los Angeles County, making it easier for nonprofits such as Goodwill Industries and the Salvation Army to set up shop in neighborhood business districts.

The county code revision, which expands the commercial areas in which vintage stores can do business, was proposed last year by Supervisor Don Knabe after a request from Goodwill, but represented a long-overdue updating of the zoning code, says Bruce Durbin, supervising regional planner in the Department of Regional Planning’s ordinance studies section.

“Essentially, secondhand stores had been in the same zoning category as recycling yards and pawnshops,” says Durbin, noting that such stores weren’t even classified in the zoning code until the Great Depression. “The idea was that they had the same impact as, say, a place that sold scrap metal.”

But secondhand stores since then have become more like other retail outlets, he says. Indeed, the No. 1 song in the country right now is Macklemore & Ryan Lewis’ bawdy anthem, “Thrift Shop,” in which the singers vow to shop ‘til they drop—or “pop some tags”—even though they only have $20 in their pockets.

“These days, thrift shops operate like, say, a Marshall’s—they receive bulk materials, sort it, price it and put it in a showroom. So this was a matter of the zoning catching up with the use.”

The amendment allows secondhand retail stores to open in so-called C-2 zones, as long as the lot isn’t residential and all the drop-off, storage and sorting is done indoors during business hours.

At least one city expressed concern that the change might cheapen municipal shopping districts that border on unincorporated county areas. San Marino noted in a letter that thrift shops could theoretically set up shop across San Gabriel Boulevard from the upscale community, which only allows the sale of new goods.

Nonprofits, however, supported the measure, with letters and testimony from the Salvation Army, the St. Vincent de Paul Society and the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, which operates the popular Out of the Closet thrift shops.

“This ordinance is going to be great,” says Michael Pauls, a Long Beach-based land use consultant to Goodwill who predicts that it will enable the nonprofit to add as many as a half-dozen new outlets over the next two years to the 40 or so stores it now operates countywide.

Since the recession, he says, Goodwill has been trying to expand its offerings of household goods and used clothing; it also has sought to respond to a massive influx of used book donations by opening a new tier of Goodwill bookstores. But when zoning prevented the nonprofit from moving on a series of retail vacancies in unincorporated commercial areas near Santa Fe Springs, Pasadena and Hacienda Heights, Goodwill sought relief from the county.

“In the last 20 years, thrift stores have become very popular with the shopping public,” Pauls says, noting that secondhand stores not only offer low-cost shopping, but also divert used goods from landfills and, in many cases, provide jobs and job-training programs.

“We’re no longer the rummage sales or ‘Sanford and Son’ image that people often equate with us.”

Posted 2/27/13

She’s the new jailer in town

February 22, 2013

Terri McDonald, formerly a top California correction's official, will oversee L.A. County's troubled lock-up.

Terri McDonald is taking a break in one of her favorite places, the warden’s office at Folsom State Prison. She’s sentimental about the whole place, with its thick granite walls and colorful history as one of America’s oldest operating prisons. Years back, she worked there as a captain. More recently, she’s been overseeing it—along with 32 other California lockdowns—as operations chief for the state’s penal system, the largest in the nation.

On this day, during an interview with a caller from Los Angeles, she sounds more like a social scientist than a prison boss. “They are their own communities,” she says of the state institutions, “each with its own ebb and flow, each with its own subculture.”

Behind the walls, she says, you’ll find “the most complicated people in California,” men and women “too problematic to be in society,” thrown together with an undercurrent of “gang allegiances and sociopathic influences.” Some inmates might be only 18 years old, she says, others 90. Some may have developmental disabilities, others Ph.D.’s.

“It’s just fascinating,” McDonald says enthusiastically. “I can’t wait to see how L.A. works.”

Come March, she’ll get that opportunity when she assumes her newest—and, arguably, her highest profile—position during a quarter-century career in corrections; McDonald has been selected as assistant sheriff for the custody division of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department—a post created as one of the top priorities of the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence. McDonald, 49, also will hold the distinction of being the highest-ranking woman in the department’s history.

“It’ll be a challenge,” she says of the new job, “but certainly not overwhelming.”

McDonald’s selection by Sheriff Lee Baca represents a significant departure for the department, which historically has promoted from within. The blue-ribbon jail panel stressed the importance of naming an outsider to the new custody position, someone with a record of success in managing a large corrections facility or department. In its final report in September, the panel noted that the previous three assistant sheriffs responsible for custody operations had come from the department’s patrol side “and none had any recent experience in the jails.”

The panel, whose members were appointed by the Board of Supervisors, also recommended that the new position report directly to Baca to enhance accountability and “remove the filtering process that accounts, in part, for the Sheriff not knowing of ‘bad news,’ while at the same time reducing [Undersheriff Paul Tanaka’s] influence over Custody operations.” The jail commission blamed Tanaka for undermining efforts aimed at reducing brutality among some deputies assigned to the county jail system, which is managed by the Sheriff’s Department.

In the wake of the findings, Baca acknowledged management failures of his own and agreed to implement the panel’s 60 recommendations, including conducting a nationwide search for the job McDonald cinched.

“My expectation for her is to tell me the good, the bad and the ugly and to proactively head off problems, solving them before they get out of control,” Baca says. “This was a gap that needed to be closed.”

Baca emphasized, as did the commission, that he has made substantial progress already in reducing the use of unnecessary force in the jail and expects McDonald to build on those reforms and others, including the expansion of inmate educational programs.

The commission’s general counsel, Richard Drooyan, says McDonald “certainly has the experience and background” to tackle the problems uncovered during the panel’s nearly year-long investigation. “I think it helped bringing in someone from the outside to restore credibility to the process,” says Drooyan, who is now monitoring the department’s implementation of the commission’s reforms.

McDonald, who grew up in the small Stanislaus County town of Oakdale, went to work for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation at the age of 25, specializing in inmate mental health issues. Since 2011, she’s been functioning as undersecretary of operations, overseeing adult institutions, parole operations, juvenile justice and rehabilitative programs. Among other things, she says that, because of massive overcrowding, she was responsible for moving 10,000 inmates to five other states, giving her a national perspective on prison models.

During the past year, her state job also has brought her into direct contact—and sometimes conflict—with Los Angeles County. She’s been the California prison system’s point person for “realignment,” the highly controversial shift of certain oversight and incarceration responsibilities from the state to its counties. It’s been her job to coordinate this unprecedented remaking of the state criminal justice system with local probation officials, sheriff’s departments and mental health experts.

Now, she’ll be on the hook for managing the fallout in L.A. County’s jails, where thousands of inmates are being sentenced for crimes that used to land them in state custody—and for terms longer than those previously imposed on county jail defendants. “In my new role,” she says, “I’ll have the opportunity to see the impact and work on solutions.”

As for the scandal of excessive force in the county’s jail that led to her landing the $223,087-a-year job, McDonald says she’s up for the task. She notes, among other things, that she was a “master trainer” for the state’s use of force policy and was instrumental in revamping the training academy’s ethics curriculum.

“I understand the realities of working in correctional environments and how to make fundamental changes,” she says. “I’ve been in situations where I’ve been battered and been in riots. I’ve used force. I think folks have to realize that force is a reality of jails and prisons.” But, she says: “The force used must be the minimum amount to resolve the problem and not used as punishment.”

Posted 2/22/13

Here’s a car-free route to the beach

February 22, 2013

However you roll, you won’t want to miss the next CicLAvia, which blazes a new trail through the Westside before culminating at Venice Beach.

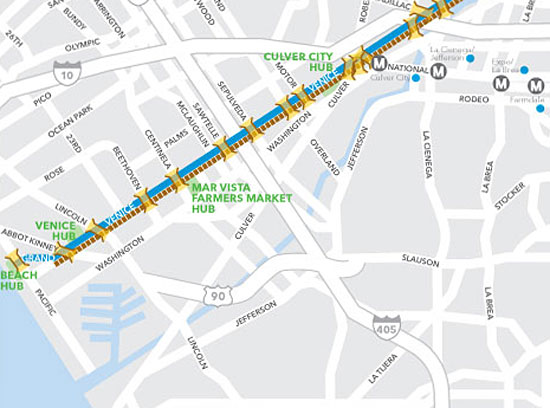

The map for the April CicLAvia was released this week, showcasing the event’s longest route so far, stretching about 15 ¼ miles between City Hall and Venice Beach. It follows Venice Boulevard most of the way, although there are shorter stretches on Figueroa, Main and 2nd streets downtown.

Since 2010, the popular bike and pedestrian events have reached out to new communities while opening up some of L.A.’s streets for healthy car-free fun. This is CicLAvia’s deepest foray yet into the Westside.

The moveable street party runs from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. on Sunday, April 21.

CicLAvia “hubs”—providing meet-up places and pit stops for refreshments, relaxation, and bike repairs—will be located at El Pueblo, City Hall, Normandie Avenue and along Venice Boulevard in the Fairfax District, Culver City, the Mar Vista Farmers’ Market, near Abbot Kinney and at the beach .

Posted 2/22/13

Meet L.A.’s oldest meteoric stars

February 22, 2013

Last week’s Russian meteor strike may have been astonishing (not to mention hazardous to thousands of Siberians), but great balls of fire can land anywhere—even in greater Los Angeles.

Take the 30-pound Neenach meteorite—4.5 billion years old, give or take a few hundred million—that was turned up by a plow in 1948 by an Antelope Valley rancher. Or the 42-pound Littlerock meteorite, found on a farm in 1979 near Palmdale.

There are even a pair of rare Martian meteorites named for Los Angeles County, though technically the collector who discovered them said he can’t recall precisely where in the Mojave Desert he stumbled across them; the two lava chunks, weighing about a pound and a half-pound, respectively, languished for nearly two decades in a box of loose rocks at his home in Sunland, until he took them in 1999 to UCLA for testing.

Now, a thin slice of “Los Angeles 002,” as the smaller meteorite is now known, is behind glass at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, along with the other aforementioned local examples of primordial stardust.

“Meteorites are hitting the Earth constantly,” notes Alyssa R. Morgan, collections manager in the gems and minerals department of the Natural History Museum.

“Most of them are as tiny as dust or sand grains, but they make the Earth bigger every day.”

Like geologists the world over, Morgan’s mind has been on last Friday’s extraterrestrial fly-by as the museum has braced for Los Angeles’ usual response to meteor-related publicity. The meteorite, which is estimated to have been 55 feet in diameter, rained black and brown fragments for miles across the snow as it streaked across the Ural Mountains, shattering windows and injuring some 1,200 people. Though the bulk of it has yet to be recovered, it is believed to be the largest such object to have hurtled to Earth in more than 100 years.

“Usually after a newsworthy event like the one in Russia, we get lots of calls from people saying, ‘You know, I found this funky rock a while ago and I’ve been meaning to have it tested’,” says Morgan, who has been fascinated by meteorites since her childhood in Seattle, and who studied moon rocks as a graduate student at Brown University. “Ninety-nine times out of 100, they’re not meteorites.

“We have had some real ones come in, though. Last year, a guy who buys storage lockers at auctions brought in a box of rocks so carefully wrapped that he figured the person he’d bought them from had to have been a collector. It turned out he was right, although we never did hear what he decided to do with them.”

Meteorites are meteors—typically asteroids or fragments of asteroids, moons or planets—that have made it through the Earth’s atmosphere and landed.

Some meteorites, Morgan says, are remnants of planets shattered long ago in collisions; others are chunks of existing planets and moons that were chipped at extreme velocity by other meteorites.

No meteorite is believed to have ever killed a human being, though they’ve reportedly landed several times on houses, workplaces and, in at least one verified instance, a doctor’s office in Virginia. In 1911, the famous Nakhla meteorite allegedly killed a dog in Egypt (though that’s been disputed.)

But all meteorites, she says, are time capsules.

“They’re primitive pieces of what everything in our solar system, including our sun, is made of,” says Morgan. “That’s part of why meteorites give us tremendous insight.”

The Natural History Museum’s meteorite collection is modest compared to those, say, at the Smithsonian Institution or the research collection at the Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics at UCLA.

Morgan says the NHM collection currently has about 50 specimens. One, a piece of the Argentine Campo del Cielo meteorite, was purchased especially for the new Dinosaur Hall to help illustrate the ongoing debate over whether climate change or a catastrophic meteor strike cleared the way for the age of mammals.

But the most notable other specimens are on display in the museum’s Gem and Mineral Hall. They range from a coin-sized sliver of a rare lunar meteorite found in Libya in the late 1990s to a good-sized hunk of the Canyon Diablo meteorite, which fell in Arizona some 50,000 years ago, creating a massive crater. The latter was instrumental in the determination—by Caltech geochemist Clair Patterson in the 1950s—that the Earth is about 4.55 billion years old.

“Before that work, people knew the Earth was old, but had no way to calculate its age,” says Morgan, running her hand along the big, dark meteorite’s dented surface. “Through this rock, we learned something we now take for granted—how old we are.”

Alyssa Morgan with a chunk of the Canyon Diablo meteorite, which helped scientists determine the Earth

Posted 2/22/13

Coming down the track: Cell and Wi-Fi

February 21, 2013

It’s available at the corner coffee shop, the public library and LAX. But cell phone and wireless service on the L.A. subway? Sorry, wrong number.

After several years of study, though, that may be about to change.

A Metro committee this week approved awarding a contract to InSite Wireless to build the network and serve as the host for the various cell and data service providers whose customers will be using the service as they ride the rails or wait on station platforms.

If approved by Metro’s full board next week, it will take two years to build the underground network and get cell phone service up and running. Wi-Fi access, using the same antenna system installed for cell phones, is expected to follow.

“All the major cities are doing it—even London, which has a very old infrastructure. Paris has it on all its lines,” said project manager Daniel Lindstrom, Metro’s manager of wayside communications. In the U.S., he said, cities ranging from New York to Seattle have a system in place or in the planning phases.

“My own wife is saying, ‘When are you going to get that installed so I can get ahold of you?’ ”

A report to Metro’s Executive Management Committee said the agency stands to receive at least $360,000 annually from the new system—and its share of revenue from InSite could go much higher. The report said that Bay Area Rapid Transit in northern California reported $2 million a year in new revenue after installation of cell and data services.

Passengers won’t pay extra to use their phones on the subway, but their service providers would pay a fee to InSite, which would split a portion of that revenue with Metro.

After reviewing networks in place in San Francisco, Boston and Washington, D.C., Metro concluded that “the transit experience is significantly enhanced and overall personnel and business productivity has increased when patrons have cell phone and Wi-Fi access.”

What’s more, the report said, Amtrak experienced a 2% jump in ridership since the service was installed in its trains.

Cell phone service also is expected to make it easier for public safety officials to respond to emergencies, and to make passengers feel safer when they’re on the subway or waiting on the platform.

Posted 2/21/13

Getting their just rewards

February 14, 2013

A county reward helped authorities find the Glendale driver in a fatal hit-and-run. Photo/Bryan Frank

Just hours before fugitive ex-cop Christopher Dorner was finally cornered in a hijacked cabin near Big Bear, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors had joined the manhunt: On Tuesday morning, it authorized a $100,000 reward for his capture, on top of the $1 million offered in private and public funds by the City of Los Angeles.

Now, with the quadruple murder suspect dead, it’s unclear exactly how—or if—the county’s bounty will be doled out to those who’ll inevitably step forward asserting that their information was crucial in Dorner’s discovery and demise. Ultimately, under county law, a recommendation will be made by representatives of the Chief Executive Office, Sheriff’s Department and Board of Supervisors, whose five members will have the final say.

The Dorner reward made news, of course, because of the international magnitude of the case, upstaging even President Obama’s State of the Union address as the drama came to a fiery conclusion Tuesday evening. But with less fanfare, the county for decades has been offering and paying rewards for information that has helped authorities obtain convictions for crimes ranging from multiple murders, to racially-inspired vandalism to animal cruelty.

During the past five years, the Board of Supervisors has authorized more than 140 reward offers—totaling $1.9 million—on behalf of law enforcement agencies throughout the county. Of those, the county has paid 25 claims worth about $225,000. The biggest payout came last April, when 10 people shared $30,000 for providing information that led to the arrest and conviction of assailants in the so-called “49th Street Massacre.” In that 2006 tragedy, three people, including a 10-year-old boy on a bike, were gunned down in a mistaken identity gang shooting in South Los Angeles.

Over the years, questions have been raised about how crimes are selected for rewards and whether the publicity surrounding a case—or the victim’s race—might unduly tip the scales. In the late 1990s, entertainer Bill Cosby asked that several taxpayer-funded reward offers be rescinded after his son, Ennis, was murdered while changing a tire on a darkened road near Bel Air. The family did not want to make it appear they were getting preferential treatment. Although the state and City of Los Angeles declined Cosby’s request, the Board of Supervisors withdrew its $12,500 reward.

For the most part, however, law enforcement officials dismiss such concerns and criticisms, saying they only seek rewards from the supervisors or other municipal bodies when investigations of particularly heinous crimes go cold and the public remains at risk.

“They are effective, absolutely,” Sheriff’s Department spokesman Steve Whitmore says, although he acknowledges that the offer of money can make investigations more complicated. “A lot of the tips aren’t fruitful,” he says. “But the important thing is that a lot of them are.”

Such was the case for frustrated Glendale Police Department detectives, whose investigation into the hit-and-run death of Elizabeth Sandoval in 2007 was at a standstill. The 24-year-old woman was thrown 100 feet after she was struck by a black Mercedes-Benz as she jaywalked across Glendale Avenue in the darkness of night.

“If the driver could just look into their heart and see that things would be better for him or her if they came forward,” Sandoval’s grief-stricken father pleaded after his daughter’s death. “Just do yourself a favor and turn yourself in,” her brother urged.

But it wasn’t until the Glendale City Council and the L.A. County Board of Supervisors each offered $10,000 in reward money that police got a breakthrough that led to the arrest and conviction of Ara Grigoryan, 23, who, according to the informant, had fled to Mexico.

Without the reward, says Glendale police spokesman Sgt. Tom Lorenz, “it would never have gotten solved.” The informant, he says, “made it very clear to us that she called because there was an offer of a reward…She kept calling back until she got the money.”

Long Beach police officials, meanwhile, credit a $25,000 county reward with helping them crack one their biggest cases in recent years—the 2006 murder of Los Angeles County Deputy Sheriff Maria Cecilia Rosa. She was shot twice just after dawn by robbers while loading bags into her car before heading from Long Beach to her assignment in the county jails. “It was a coldblooded killing,” Sheriff Baca told the media. “Who is truly safe? No one.”

A little more than a month after the reward offer, an informant gave Long Beach police the name of the suspected gunman and arranged a meeting between detectives and another individual who revealed where one suspect was believed to be living. In the end, two men—both of whom were already serving state prison time—were convicted in the deputy’s murder. One was sentenced to death; the other was given 29 years to life.

“The reward prompted an otherwise unwilling witness to come forward and provide information which allowed detectives to focus on a small group of suspects,” says Long Beach police spokesman Sgt. Aaron Eaton.

Long Beach police also benefitted from another reward offered by the county—this one involving the murder of popular honors student Melody Ross, 16, who was hit by gunfire that was sprayed into a group of young people leaving the 2009 Wilson High School homecoming football game. Two witnesses shared the $20,000 reward after giving authorities information that led to the arrest and conviction of two teenaged defendants.

Financial incentives, Easton says, “sometimes mean the difference between making an arrest or the case going unsolved.”

But not always.

The largest county reward anyone can remember—$150,000—was first offered in late 2002, after the death of 15-year-old Brenda Sierra, whose body was found off a mountainous road in San Bernardino County. She died from a blow to the head. The unusually high reward was approved by the board at the request of Supervisor Gloria Molina, whose district includes East Los Angeles, where the teenager lived and was last seen alive.

For nearly a decade, the reward was repeatedly renewed for six-month stretches in the hopes that someone would come forward and bring a measure of closure to the long grieving family. “Until we find her killer, we’re not giving up,” Molina said in announcing the award’s extension in July, 2009.

The reward finally expired in mid-2010, and the case remains unsolved.

Police got a break in the "49th Street Massacre" case thanks to a $30,000 reward. Photo/Los Angeles Times

Posted 2/14/13

Smokers got you down? Light up a line.

February 14, 2013

So the neighbor is polluting your place with cigarette smoke. Who you gonna call?

For a growing number of Southern Californians, it’s the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

For years, the department’s Tobacco Control and Prevention Program has manned a phone line for complaints about those who flouted state laws against smoking, and for years, those calls mostly involved bars, restaurants and workplaces.

Lately, however, secondhand smoke wafting into apartments, condos and nursing home units has kept the line buzzing, says Tobacco Control deputy director Monty Messex. In the last six months alone, he says, 88 such complaints have come in via the Tobacco Control complaint line, far more than in past years. Forty-two percent, he added, came from the City of Los Angeles.

“It’s possible that people are smoking more in their apartments now because there are fewer and fewer places anymore to smoke in public,” Messex says, “but I think it’s more about awareness. People are realizing they have a choice.”

Smoke-free housing has become the latest frontier in the tobacco control movement, as health advocates and apartment dwellers have sought to stop secondhand smoke from drifting out of patios, balconies and neighboring units into non-smokers’ homes.

Despite arguments from some smokers and civil libertarians who view the push as an inconvenience and intrusion, California has led the charge in clearing smoke from shared living spaces. The state Department of Public Health has aired popular TV ads depicting secondhand smoke rising from vents to threaten small children, and more than two dozen jurisdictions including Santa Monica and Calabasas have adopted ordinances that restrict smoking in multi-unit housing. Last year a state law went into effect giving landlords permission to manage smoking in rental properties.

Next month, the Los Angeles County Housing Authority, which manages and owns 3,258 public and affordable housing units, is expected to seek approval on lease changes that would ban smoking within 20 feet of its buildings. Maria Badrakhan, director of the Housing Authority’s housing management division, says the move will affect some 7,000 renters from West Hollywood and Marina Del Rey to East Los Angeles and Long Beach, but so far, residents’ reactions have been overwhelmingly positive.

“We have a lot of seniors, a lot of families and people whose children have asthma, and we receive a lot of complaints from people who don’t want smoking in their buildings,” says Badrakhan, adding that the Department of Public Health has been working with the authority to help tenants quit smoking.

“We’re trying to create a better quality of life.”

The Tobacco Control complaint line—which essentially rings during business hours into the Tobacco Control and Prevention Office at 213-351-7890—is just a small part of the county’s effort to connect victims of secondhand smoke with agencies and authorities who can help.

The DPH’s Messex says it’s a challenging assignment, given the 88 separate jurisdictions and the patchwork of municipal smoking ordinances in the county. Sometimes, he says, the response is as simple as sending a letter to the property manager or owner and referring the caller to the appropriate fire department or code enforcement unit. Often, however, the county also will send callers to organizations such as S.A.F.E. (Smokefree Air For Everyone), a Granada Hills-based advocacy organization that operates an online, smokefree apartment registry.

“More and more people have come to us from the county,” says S.A.F.E.’s associate director, Marlene Gomez. “We’re getting 5 to 10 calls a week, and email in droves.”

Some of the complaints are heart-wrenching, says Gomez. “I had one case where a mother called from a rent control apartment in Wilmington with three kids—a 4-year-old, a 5-year-old and a 4-month-old baby—and the 5-year-old has asthma and smokers had moved in downstairs.”

In that case, she says, she was able to persuade the landlord to move the family to a different apartment and to let him know that he could keep smokers away in the future by specifying units as non-smoking as they became vacant.

But for many of those who complain, Messex says, recourse is limited because restrictions have yet to be enacted by the state or by most of the municipalities in the county, including the City of Los Angeles, and the bans that do exist vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

“There’s not a lot we can do,” he says. “And in some cases, the situation is pretty severe.”

Apartment dwellers like Cris Borgnine say comprehensive restrictions would make a difference. Borgnine, a 46-year-old cameraman and photographer with two little boys at home, aged 3 and 7, says he started searching for help after smokers moved in not only next door, but also around the corner and downstairs from his North Hollywood apartment.

“It’s been really frustrating,” Borgnine says. “The smoke comes up through the kitchen fans and the heating ducts. When the onshore breeze blows, it comes in through our bedroom window. When you’re having dinner, it’s awful.”

In addition to his concern for his family’s health and the impact on his quality of life, Borgnine adds, his irritation had a personal angle: His father, the late actor Ernest Borgnine, had to have throat surgery at one point in his life because of complications from smoking. So when calls to the apartment manager failed to persuade his neighbors, he started dialing.

Eventually, he says, he got through to the county’s complaint line, only to learn that little could be done in his jurisdiction, other than sending his property manager a letter.

“We really need to do something about this,” he says. “Fortunately, my family and I have the resources to move to a new place, but the next person to move in is still going to have to deal with it.”

Posted 2/14/13

Look who’s in the fast lane

February 7, 2013

As Los Angeles learns the ins and outs of its first toll roads, the agency behind the pilot project is taking a look at who the early adopters are.

And wondering why folks in Tenafly, New Jersey, Peoria, Illinois and Peterborough, New Hampshire saw fit to purchase one of the new transponders to drive on the 11-mile stretch of ExpressLanes on the 110 Freeway south of downtown L.A.

“Maybe they’re business travelers. Maybe they’re the parents of students going to school out here,” said Stephanie Wiggins, who manages the ExpressLanes project for Metro and says she expects to learn more about the out-of-town phenomenon as research continues.

As it stands now, people from more than 400 cities and towns in California and across the country as far away as Honolulu have purchased FasTrak transponders since the program started in November.

Most, however, are from Los Angeles County—where Metro’s ZIP code analysis shows that Los Angeles residents are the top transponder buyers, followed by people in Torrance, Redondo Beach and Long Beach. The Top 10 also includes residents of more northerly communities like Pasadena and Glendale.

Some 88,000 transponders were in circulation as of Tuesday, putting the project on a fast track toward reaching its goal of 100,000 in its first year of operation.

A second set of toll lanes, running for 14 miles on the 10 Freeway between Alameda Street in downtown Los Angeles and the 605 Freeway, is set to open on Feb. 23.

As Metro and Caltrans prepare to roll out the lanes on the 10, they’re analyzing what they’ve learned so far and how to apply it.

For example, outreach is being stepped up to include 230 religious institutions along the 110 corridor, where brochures will be distributed and “pulpit presentations” are planned, either by clergy or ExpressLanes representatives.

“Faith-based organizations are a powerful forum for getting information out to community members,” Wiggins said.

They’re also a good place to get out the word about the program’s “equity plan,” in which low-income households can get a transponder for $15—instead of the $40 usually required. Smaller discounts for transponders, which work on toll lanes throughout California, not just in L.A. County, are available when purchased through the Automobile Club of Southern California, Costco and Albertsons.

There have been no accidents attributed to the ExpressLanes, but officials are increasing signage to make sure motorists know the rules of the road. Wiggins said there have been reports of “near-misses” on the 110 involving drivers who have dangerously crossed the double white lines between the toll lanes and regular lanes, perhaps trying to avoid a fine for getting caught on camera without a transponder.

Another side effect of the toll lanes: traffic has gotten more congested in the freeway lanes next to them. Wiggins said that traffic should eventually revert to normal as motorists become familiar with the stretch and the influx of CHP officers now patrolling it.

On another front, Metro’s Board of Directors is considering whether to scrap the program’s $3 monthly maintenance fee, which is charged to occasional users who drive in the lanes fewer than four times a month. Supervisor and Metro Director Zev Yaroslavsky contends in a motion that the fee should be dropped as a matter of fairness.

The ExpressLanes replaced what was formerly a high-occupancy vehicle lane on the 110. But Metro’s analysis shows that carpoolers—who ride for free in the new lanes as long as they purchase a transponder—still represent 62% of the customers so far and have been using the lanes most heavily between 7 a.m. and 8 a.m.

Solo drivers, who pay tolls when they use the lanes, make up 38% of ExpressLanes users and are out in greatest force between 8 a.m. and 9 a.m.

Overall, the number of daily trips is increasing, from 39,820 in mid-November to 43,900 by mid-January.

For those overseeing the pilot project, though, the most important number is 45—as in miles per hour. That’s the minimum average speed the lanes must achieve to be considered a success, under the terms of the $210 million federal grant that’s paying for them.

So far, they’ve been up to speed 100% of the time.

Posted 2/7/13

Beverly Hills cultivates some history

February 7, 2013

Virginia Robinson put Beverly Hills on the map as an enclave of the rich and famous. Now, more than a century later, Beverly Hills has returned the favor to its storied grand dame.

The Virginia Robinson Gardens, bequeathed to Los Angeles County after its namesake’s death in 1977, last month became an official local historic landmark. Built in 1911 by the Robinson’s department store heir Harry Winchester Robinson and his then-new bride, Virginia, the 6½-acre estate on Elden Way—now run under the auspices of the Los Angeles County Department of Parks and Recreation—has long held landmark status at the state and national level.

“This was essentially the first great estate in Beverly Hills,” explains Robinson Gardens Superintendent Timothy Lindsay.

But Beverly Hills created its historic designation only a year ago, prompted by the near-demolition of an architecturally significant house designed by Richard Neutra. The city has since named seven local landmarks, with more in the pipeline, according to Noah Furie, a former Beverly Hills planning commissioner and founding chairman of the city’s new Cultural Heritage Commission.

The Robinson estate was the second property in the city to receive the designation, after the neighboring Beverly Hills Hotel.

“This is one of the most unique properties in our city,” says Furie. “With all its different types of gardens, and its owners being the founders of one of Los Angeles’ most important department store chains, and their many contributions to the immediate and greater community, it checked off multiple criteria in our ordinance.”

Furie says the new local ordinance has proven to be a milestone for Beverly Hills. Even before the aborted demolition of Neutra’s Kronish House in 2011, preservationists had feared for the city’s architectural history.

“It was getting to the point that, if we didn’t do something, our past would be lost forever,” he says. “Significant estates done by master architects had been subdivided into multiple properties. We’d lost, including major remodels, the Burton Green estate, the Max Whittier estate, the Gershwin House—the list is a mile long.”

The new preservation ordinance imposes strict rules for changing or demolishing buildings that are older than 45 years and that either have some historic or cultural significance or are designed by master architects.

The Robinsons discovered their site in the early 1900s while searching for the Los Angeles Country Club in what was then the rural edge of the city. When they finished the house, designed for them as a wedding gift by Virginia’s father, architect Nathaniel Dryden, fields of barley stretched before them to the horizon.

But as the city grew up, the property, which was landscaped by Virginia and a dozen full-time gardeners into an expansive collection of lush, terraced gardens, became a public gathering place and an A-list destination. The Italianate pool house alone was 3,000 square feet and the palm grove still boasts the largest collection of Australian king palms in the continental United States.

Celebrities from Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks to Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers cavorted at the Robinsons’ lavish parties, as did a who’s who of Southern California society and business. Even after Harry Robinson died in 1932, Virginia—who took over the department store chain that her husband’s father had founded—maintained the civic momentum, accompanied by her beloved pets (she never had children and never remarried). For 33 years, her home was the site of a famed Hollywood Bowl kickoff gala; her last major domo came from the Vatican and spoke five languages, according to the estate superintendent Lindsay.

“Virginia Robinson worked with Dorothy Chandler to build the Music Center, she was great friends with Lillian Disney and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor,” Lindsay says.

And, he adds, Virginia adhered to a level of hospitality that would have impressed Downton Abbey.

“She had a large staff of 21 trained in the same level of etiquette as the White House,” says Lindsay. “After 6 p.m., the men all had to put on black tie and tails. Invitations were handwritten. There was always valet parking. When you arrived at the house, one man in white gloves would open the gate and another would open the door and announce your arrival, and she would meet you in the receiving line.

“Remember, Southern California was still pretty much a dusty cowboy town, in those days. But she set a standard for gracious living. She had a legendary elegance.”

Posted 2/7/13

Check for the latest closure information

Check for the latest closure information